www.jped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Association

between

socioeconomic

and

biological

factors

and

infant

weight

gain:

Brazilian

Demographic

and

Health

Survey

---

PNDS-2006/07

夽

,

夽夽

Jonas

Augusto

C.

Silveira

a,∗,

Fernando

Antônio

B.

Colugnati

b,

Ana

Paula

Poblacion

a,

José

Augusto

A.C.

Taddei

aaDepartmentofPediatrics,UniversidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo(UNIFESP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

bNúcleoInterdisciplinardeEstudosePesquisasemNefrologia(NIEPEN),NephrologyDivision,

UniversidadeFederaldeJuizdeFora(UFJF),JuizdeFora,MG,Brazil

Received30April2014;accepted27August2014 Availableonline13February2015

KEYWORDS

Child; Weightgain;

Nutritionaldisorders; Surveys;

Brazil

Abstract

Objective: To examine the associations between socioeconomic and biological factors and

infantweightgain.

Methods: All infants (0-23 months of age) with available birth and postnatal weight data

(n=1763) wereselectedfromthelastnationally representativesurveywith complex

prob-abilitysamplingconductedinBrazil(2006/07).Theoutcomevariablewasconditionalweight

gain(CWG), which represents howmuch anindividualhas deviatedfrom his/herexpected

weightgain,giventhebirthweight.Associationswereestimatedusingsimpleandhierarchical

multiplelinearregression,consideringthesurveysamplingdesign,andpresentedinstandard

deviationsofCWGwiththeirrespective95%ofconfidenceintervals.Hierarchicalmodelswere

designedconsideringtheUNICEFConceptualFrameworkforMalnutrition(basic,underlyingand

immediatecauses).

Results: The poorest Brazilian regions (-0.14 [-0.25;-0.04]) andrural areas (-0.14

[-0.26;-0.02])wereinverselyassociatedwithCWGinthebasiccausesmodel.However,thisassociation

disappearedafteradjustingformaternalandhouseholdcharacteristics.Inthefinalhierarchical

夽 Pleasecitethisarticleas:SilveiraJA,ColugnatiFA,PoblacionAP,TaddeiJA.Associationbetweensocioeconomicandbiologicalfactors andinfantweightgain:BrazilianDemographicandHealthSurvey---PNDS-2006/07.JPediatr(RioJ).2015;91:284---91.

夽夽

StudyconductedatDepartamentodePediatria,UniversidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo(UNIFESP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil. ∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:jonasnutri@yahoo.com.br(J.A.C.Silveira). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2014.08.013

WeightgainamongBrazilianinfants 285

model,lowereconomicstatus(-0.09[-0.15;-0.03]),humancapitaloutcomes(maternal

edu-cation<4thgrade(-0.14[-0.29;0.01]),highermaternalheight(0.02[0.01;0.03])),andfeverin

thepast2weeks(-0.13[-0.26;-0.01])wereassociatedwithpostnatalweightgain.

Conclusion: The results showed thatpoverty and lowerhuman capital arestill key factors

associatedwithpoorpostnatalweightgain.Theapproachusedintheseanalyseswassensitive

tocharacterize inequalities amongdifferentsocioeconomiccontextsandtoidentify factors

associatedwithCWGindifferentlevelsofdetermination.

©2015SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Crianc¸a; GanhodePeso; Distúrbios Nutricionais; Inquéritos; Brasil

Associac¸ãoentrefatoressocioeconômicosebiológicoseoganhodepesode lactentes:PesquisaNacionaldeDemografiaeSaúde(PNDS)de2006/07

Resumo

Objetivo: Examinarasassociac¸ões entrefatoressocioeconômicos ebiológicoseoganhode

pesodelactentes.

Métodos: Foramselecionadostodososlactentes(0-23mesesdeidade)comdadosdepesoao

nascerepós-natalavaliadosnaúltimapesquisacomrepresentatividadenacionalrealizadano

Brasil(2006/07)poramostragemprobabilísticacomplexa.AvariávelderesultadofoioEvoluc¸ão

PonderalCondicional(CWG),querepresentaquantoumindivíduodesvioudeseuganhodepeso

esperado,considerandoopesoaonascer.Asassociac¸õesforamestimadasutilizandoregressão

linearsimplesemúltiplahierárquica,considerandooplanoamostaldapesquisaeapresentadas

emdesviospadrãodoCWGcomseusrespectivosintervalosdeconfianc¸ade95%.Osmodelos

hierárquicosforamestruturadosconsiderandooModeloConceitualdeDesnutric¸ãodaUNICEF

(causasbásicas,inerenteseimediatas).

Resultados: Asregiõesbrasileirasmaispobres(-0,14[-0,25;-0,04])eaárearural

(-0,14[-0,26;-0,02]) foraminversamenteassociadas ao CWG nomodelo decausasbásicas.Contudo,essa

associac¸ãodesapareceuapósoajustepelascaracterísticasmaternasedoambientefamiliar.

Nomodelohierárquicofinal,abaixacondic¸ãoeconômica(-0,09[-0,15;-0,03]),asvariáveisde

capitalhumano(escolaridadematerna<5◦ano(-0,14[-0,29;-0,01])),maiorestaturamaterna

(0,02[0,01;0,03]))efebrenasduassemanasanterioresàpesquisa(-0,13[-0,26;-0,01])foram

inversamenteassociadasaoganhodepesopós-natal.

Conclusão: Osresultadosmostraramqueapobrezaebaixocapitalhumanoaindasãofatores

fundamentaisassociadosaoganhodepesopós-natalabaixodeesperado.Aabordagemutilizada

emnossasanálisesfoisensívelaocaracterizardesigualdadesentrediferentescontextos

socioe-conômicoseaoidentificarfatoresassociadosaoCWGemdiferentesníveisdedeterminac¸ão.

©2015SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Todososdireitos

reservados.

Introduction

Nutritionaldisordersarecyclicallydeterminedbycultural, social,economic,andbiologicalfactorsatdifferentlevels, fromthemost proximal,suchasfoodavailabilityand the occurrenceof diseases,todistalfactorssuchasaccessto informationandtheculturalsuperstructure.1,2

The first twoyears of life are characterized by accel-erated growth and development, which require high nutritional intake and define infants as a group with high biological vulnerability, especially considering that, by this time, growth and development are more strongly determined by environmental factors than by genetic characteristics.3,4 Nutritional disorders beginning in this

period areassociated with increased mortality, increased susceptibilitytoinfectiousdiseases,impairedpsychomotor development,academicunderachievement,andlower pro-ductivecapacityinadulthood.1,4---6

InBrazil,thepredominantnutritionandhealthpolicies and programs, such as the exclusive breastfeeding cam-paign, immunization and supplementation programs, and the food fortification initiative, address infants and their mothers. The main Brazilian social support programs are knownas ‘‘FomeZero’’ and ‘‘Plano Brasil Sem Miséria’’, whichaimtopromotehouseholdfoodsecurityandautonomy forlow-incomefamiliesbymeansofconditionalcash trans-fers,thefundingoffamilyfarming,andaid forpurchasing goodsandservices.7,8

Nationalhealthsurveysareimportanttoolstoevaluate suchpublicpoliciesbecausetheydescribethe healthand nutritionprofileofthepopulation,identifyingriskfactors, toallow comparisonsamongregionsandcountriesaswell astheplottingoftrendsovertime.9,10Therefore,giventhe

significance of children’s growthin the first twoyears of life3 and using data from the last Brazilian National

(PNDS-2006/07),thisstudyaimed toexaminethe associa-tionsbetweensocioeconomicandbiologicalconditionsand postnatalweightgain.

Materials

and

methods

Studydesignandsettings

ThePNDS-2006/07wasanationalsurveyconductedbetween Novemberof2006andMayof2007,focusedonthehealth andnutritionofwomenofreproductiveage(15-49yearsold) andchildrenunder5yearsofage,includingsocial,economic andculturalfactors.ThePNDS-2006/07usedcomplex prob-abilitysamplingintwostages:theprimarysamplingunitwas thecensusarea,andthesecondary samplingunitwasthe household.The studygroupcomprisedonlyprivate house-holds (includingslums).Eligible households wereselected atrandom,takingintoaccountthenumberofcensusareas ineachregionandtheurban/ruralareas.Furtherdetailson methodology,includingsamplingdesignanddatacollection, havebeenreportedelsewhere.11

Eligibilityandselectioncriteria

The households considered eligible included at least one womanofreproductive age.Data werecollectedfromall childrenunder59monthsforeacheligiblemother.Forthe purposeofthisstudy,theauthorsselectedthesubgroupof infants(0---23monthsofage)livinginthesamehouseastheir mothers.

Datacollectionandvariablesdefinition

Datawerecollectedbypairsoftrainedfemalefield work-ers in the children’s residence. Children were weighed usingan electronic portable scale (Y60) withprecision of 100g(Dayhome®,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil).11 Birthweightwas

collected from the child’s maternity card, and when not available,bymother’srecall.Weight-for-ageZ-score(WAZ) wascalculatedusingmacrosoftheWorldHealth Organiza-tion(WHO)AnthroSoftwareversion3.2.2forStataandthe WHOChildGrowthStandardswereusedforanthropometric classification.12

Conditionalweightgain (CWG) ---the outcome variable ---representsachild’sdeviationfromtheexpectedweight gain,givenhis/herbirthweight,andisexpressedinstandard deviations(SD).CWGisderivedfromthestandardized resid-ualsobtainedfromasex-specificlinearregressionadjusted forWAZatbirthandageatsurvey,whereWAZatsurveyis thedependentvariable.

It is important to consider this approach in longitudi-nal analysisof individuals’growth, sinceit: 1)overcomes the statistical phenomenon of regression to the mean, whereextreme values tend tomove closertothe sample mean;2) incorporatesthedifferentagesatsurvey’sdate; and, 3) deals with the collinearity of dependent weight measures.13,14Forexample,ifachildwithhighbirthweight

reduceshisorherWAZ,likewisefortherestofthechildren inthe sample whowere born withhigh birth weight,the CWGwouldbe∼0SD;but,inacounterfactualperspective,

ifthischildkeepsthesameWAZwhentherestofthe sam-ple’sWAZtendstoreduce,hisorherCWGwouldbegreater thanzeroSD.

Therationalefortheselectionoftheexposurevariables wasbasedonUNICEF’sConceptualFrameworkof Malnutri-tion,whichconsidersthebasic,underlying,andimmediate determinants.TheConceptualFrameworkofMalnutritionis ausefultoolthathelpstoorganizepossiblecausesof nutri-tionaldisordersandidentifysituationswhereinvestigations orinterventionsarerequired.2

Twovariableswereincluded asbasiccauses:children’s areaofresidence(urban/rural)andregions, dichotomized asSouthandSoutheastorasNorth,Northeast,andMidwest; this approach wasused to contrastsocioeconomic differ-ences,thelatterregionsbeingmoredeprived.

Asunderlyingcauses,somehouseholdandmaternal fac-tors were considered. Economic statuswas assessed by a validatedasset-basedquestionnaire,whichclassifies house-holds into eight mean family income categories,15 which

werereducedtofourcategories(A1-C1/C2/D/E);the cat-egories A1-C1(richest) weremerged toproducebalanced cellsizes in eachcategory.Household foodinsecuritywas assessedusingtheBrazilianFoodInsecurityScale (EBIA,in Portuguese)atranslatedandvalidatedversionoftheUSDA FoodSecurityModule,knowncurrentlyastheUSHousehold FoodSecuritySurveyMeasure---whichclassifiesthe house-hold’s in food security level asmild, moderate or severe foodinsecurity.16,17Humancapitaloutcomes(maternal

edu-cationlevel[<4thgrade]andheight[cm]),ageatbirth(<18 years),parity(numberofdeliveries),prenatalcare(number ofvisits),andtypeofdelivery(vaginal/caesarean)werealso included.

Lastly,feverordiarrheaintheprevioustwoweeks; hos-pitalization due to diarrhea, pneumonia, or bronchitis in theprevious 12 months;durationofexclusive breastfeed-ing(<1month/1-4months/>4months);age;andsexwere consideredasbasiccauses.

Dataanalysis

DataweremergedandanalyzedusingStatasoftware (Stat-aCorp.2011.StataStatisticalSoftware:Release12.College Station,TX:StataCorpLP,USA),consideringthe stratifica-tionandclusteringeffectsofthecomplexsamplingdesign. Sampleweightswereonlyappliedtothedescriptive statis-ticstoavoidoverestimatingsubgroups.10

In the analytical approach, simple and multivariable linearregression analyses wereperformed. The multivari-able regression was conducted by applying a hierarchical structuretotheanalysis,18consideringtheUNICEF’s

Frame-work for Malnutrition.2 Initially, all variables were tested

byasimplelinearregressionandthosewithp-value<0.20 wereconsideredeligibleformultivariableanalyses,within eachlevelofdetermination.Then,amultivariableanalysis wasperformedforvariablesconsideredinthebasiccauses

(Model 1), adjusted for age and sex. This procedure was repeatedforthesetofunderlying(Model2)andimmediate causes(Model3).

WeightgainamongBrazilianinfants 287

WAZ, weight-for-age Z-score.

Total records from children born after Jan/2001

(n=6,011)

Exclusion criteria:

Older than 24 months (n=3,870) Died before the survey (n=99) Not living with mother (n=140)

An

alys

is

Infant national sample (n=1,902)

Exclusion criteria:

Missing birth’s or survey’s weight data or biologically implausible WAZ (n=139)

Analyzed (n=1,763)

S

am

ple

S

el

ec

ti

on ♦

♦ ♦

♦

Figure1 Flowdiagramoffinalsampleselection.

WAZ,weight-for-ageZ-score.

Model2 and1.Model3wasalsocontrolledforthesource of birth weight data (maternity card or mother’s recall). ThecoefficientswerereportedastheSDofCWGwiththeir respective95%confidenceintervals(inparenthesisorsquare bracketsthroughthetext).Followingthetechnical litera-turerecommendations,estimateswereinterpretedinterms oftheirrelevancetowardthesubject,effectsize,and inher-entuncertainties,representedhereinasthe95%confidence intervals,avoidingtheusualaccept/rejectapproachbased onthep-value<0.05cut-off.19

EthicalAspects

All procedures involving human subjects in the

PNDS-2006/07wereapprovedbytheResearchEthicsCommittee oftheCenterofReferenceandTrainingonSTD/HIVofSão Paulo’sStateHealthDepartment.Thepresentresearchwas approvedbytheResearchEthicsCommitteeofthe Univer-sidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo---CEP/UNIFESP.

Results

Of the 6,011 children born after January 2001 who were availableinthedataset,1,763wereinfants(0-23monthsof age)livinginthesamehouseastheirmothers,having biolog-icallyplausibleWAZdata(-6to+5SD)atbirthandatsurvey date(Fig.1).Thesample’scharacteristicsaredescribedin

Table1.

Diarrhea in the past two weeks, duration of exclusive breastfeedingandhospitalizationfordiarrhea,pneumonia, andbronchitisin thepast12 monthswerenotconsidered formultivariableanalyses(p-value>0.20).Sexwaskeptin themodelstoadjustforpotentialsex-relatedconfounding.

SamplelossesoccurredintheModels2and3duetomissing valuesinthedataset(Table2).

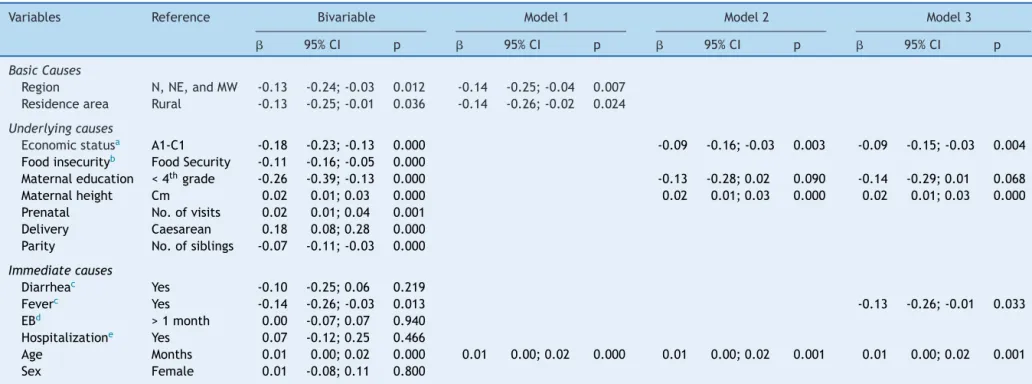

BothbasiccauseswereinverselyassociatedwiththeCWG (Table2---Model1).However,thisassociationwaslostafter adjustingthemodelforunderlyingcauses(Model2).When adjustedforimmediatecauses(Model3),economicstatus (-0.09[-0.15; -0.03]),maternal education(-0.14 [-0.29; -0.01]),andfeverinthepasttwoweeks(-0.13[-0.26;-0.01]) wereinverselyassociatedwithchildren’sweightgain. How-ever,each1cmincrementinmaternalheightwasassociated withanincreaseof0.02SD(0.01;0.03)inchildren’s post-natalweightgain.

Discussion

UsingdatafromthePNDS-2006/07,themostrecentsurvey withnationalrepresentativenessconductedinBrazil,itwas possibletoidentifythelevel ofassociation betweenaset offactors--- indifferenthierarchicallevelsofdetermination --- andpostnatalweightgainamongBrazilianinfants.Itwas foundthatlowereconomic statusandmaternal education andfeverinthepasttwoweekshadanegativeimpacton postnatalweightgain,andthatmaternal heightwas posi-tivelyassociatedwithCWG.

Although geographical factors were highly associated

withCWG in Model 1, when the maternal and household

characteristics were introduced in the hierarchicalmodel (Model2),theassociationbetweengeographicalfactorsand CWGdisappeared,andwasreplacedbyeconomicstatusand highermaternalheight;lowmaternal educationpresented onlyamoderateassociation.However,whenthethirdlevel (immediatecauses)wasintroducedintotheanalysis,fever remainedassociatedwithCWGandthelevelofassociation betweenlowmaternaleducationandCWGincreased.

Thetrajectoryofgrowthismediatedbyacomplex net-workofnon-mutuallyexclusivefactors,actingatdifferent levels of causation, from social, economic, and political determinants;followed byaccesstohealth services,food security,income,andeducationallevel;toindividualfactors relatedtotheburdenofdisease,eating/feedingpractices, metabolicprogramming,andgeneticfactors.2,3,20

The presentresults demonstratedthatlowincomeand maternaleducationallevelsarestillkeyfactorstoweight faltering. However, contrary to expected, geographical characteristics were not independent factors associated withCWG.This lackof associationmaybea consequence ofthecoverageexpansionofthepublicprimaryhealthcare systeminBrazil8and/ortheintensemigratoryprocessfrom

thepooresttotherichest regionsandfromruraltourban areas.21However,thisstatementmaynotholdtruefor

geo-graphicaldisparitieswithinneighborhoodsorcities.22,23

Besides geographicalfactors,thelack ofassociation of CWGanddiarrhea can alsobeexplained by the improve-ment of health and sanitation systems. The increased access to health services enables the provision of ade-quaterehydrationandantibiotictherapy toinfants,which prevents important acute weight loss and/or promotes faster recovery.8,24,25 Moreover, oneof the componentsof

Silveira

JA

et

al.

Table1 CharacteristicsofBrazilianinfantsfromtheBrazilianChildren’sandWomen’sDemographicandHealthSurvey---PNDS---2006/07.

Characteristics na orPb 95%CI Characteristics na orPb 95%CI

Biologicalcharacteristics Maternalheight(cm) 1,754 157.7 157.1;158.3

Age(months) 1,763 11.2 10.6;11.7 Prenatal(No.ofvisits)e 1,707 7 6;9

Gender(%) 1,763 Delivery(%) 1,762

Boys 928 52.4 47.8;57.0 Caesarean 772 45.3 40.1;50.6

Girls 835 47.6 43.0;52.2 Other 990 54.7 49.4;59.9

Birthweight(kg) 1,763 3.25 3.21;3.30 Parity(No.ofdeliveries)e 1,763 2 1;3

WAZatbirth 1,763 -0.13 -0.22;-0.03 FoodandNutritionSecurity(%) 1,710

WAZatsurvey 1,763 0.17 0.08;0.25 Security 879 53.8 48.7;58.8

Nutritionalstatusatsurvey(%) 1,763 Mildinsecurity 473 28.4 24.1;33.0

Underweight(WAZ<-2) 61 2.9 1.9;4.5 Moderateinsecurity 230 13.1 9.8;17.3 Normalweight(WAZ±2) 1,604 93.3 91.3;94.8 Severeinsecurity 128 4.7 3.6;6.2 Overweight(WAZ>2) 98 3.8 2.7;5.2

BasicCauses ImmediateCauses

Region(%) 1,763 Diarrhea(%)c 1,760

SandSE 647 54.2 48.9;59.4 Yes 233 12.2 9.8;15.1

N,NE,andMW 1,116 45.8 40.6;51.1 No 1,527 87.8 84.9;90.2

Residencearea(%) Fever(%)c 1,761

Urban 1,200 83.2 78.4;87.0 Yes 450 26.2 22.8;29.8

Rural 563 16.8 12.9;21.6 No 1,311 73.8 70.2;77.2

Hospitalizationd 1,763

UnderlyingCauses Yes 139 7.8 5.7;10.6

Economicstatus(%) 1,550 No 1,624 92.2 89.4;94.3

A1-C1(richest) 486 34.6 29.0;40.7 Exclusivebreastfeeding(%) 1,477

C2 356 23.5 19.0;28.6 <1month 502 31.8 27.2;36.8 D 446 29.1 24.4;34.2 1-4months 484 33.6 28.9;38.6 E 265 12.9 10.3;16.0 >4months 491 34.6 30.4;39.1

Maternaleducation(%)

<4thgrade 378 17.7 14.6;21.3 ≥4thgrade 1,379 82.3 78.6;85.4

,mean;P,prevalence;CI,confidenceinterval;WAZ,weight-for-ageZ-score;S,South;SE,Southeast;N,North;NE,Northeast;MW,Midwest. a Numberofsubjectsindatabase.

b Meanorprevalencebasedontheweightedsample. c Inthepasttwoweeks.

W

eight

gain

among

Brazilian

infants

289

Table2 Linearmodelsofassociationbetweenenvironmentalandindividualfactorsandconditionalweightgain(CWG)amongBrazilianinfants--- PNDS-2006/07.

Variables Reference Bivariable Model1 Model2 Model3

95%CI p  95%CI p  95%CI p  95%CI p

BasicCauses

Region N,NE,andMW -0.13 -0.24;-0.03 0.012 -0.14 -0.25;-0.04 0.007

Residencearea Rural -0.13 -0.25;-0.01 0.036 -0.14 -0.26;-0.02 0.024

Underlyingcauses

Economicstatusa A1-C1 -0.18 -0.23;-0.13 0.000 -0.09 -0.16;-0.03 0.003 -0.09 -0.15;-0.03 0.004

Foodinsecurityb FoodSecurity -0.11 -0.16;-0.05 0.000

Maternaleducation <4thgrade -0.26 -0.39;-0.13 0.000 -0.13 -0.28;0.02 0.090 -0.14 -0.29;0.01 0.068

Maternalheight Cm 0.02 0.01;0.03 0.000 0.02 0.01;0.03 0.000 0.02 0.01;0.03 0.000 Prenatal No.ofvisits 0.02 0.01;0.04 0.001

Delivery Caesarean 0.18 0.08;0.28 0.000 Parity No.ofsiblings -0.07 -0.11;-0.03 0.000

Immediatecauses

Diarrheac Yes -0.10 -0.25;0.06 0.219

Feverc Yes -0.14 -0.26;-0.03 0.013 -0.13 -0.26;-0.01 0.033

EBd >1month 0.00 -0.07;0.07 0.940

Hospitalizatione Yes 0.07 -0.12;0.25 0.466

Age Months 0.01 0.00;0.02 0.000 0.01 0.00;0.02 0.000 0.01 0.00;0.02 0.001 0.01 0.00;0.02 0.001 Sex Female 0.01 -0.08;0.11 0.800

Model1:n=1,763---adjustedforageandsex;Model2:n=1,448---adjustedforModel1,householdfoodinsecurity,prenatal,typeofdelivery,andparity;Model3:n=1,447---adjusted forModel2andsourceofbirthweightdata(maternitycard/mother’srecall).

EB,exclusivebreastfeeding. a Ordinalvariable:A1-C1,C2,D,E.

b Ordinalvariable:foodsecurity,mildfoodinsecurity,moderatefoodinsecurity,severefoodinsecurity. c Inthepasttwoweeks.

Brazil has substantially reduced nutritional disorders and mortalityratesfromacuteinfections.8,25

The associations found here depict a society in transi-tion,wheregeographicalcharacteristics or acutediseases areno longer major determinants of negativenutritional disorders, but low socioeconomic status and educational attainment still are. It contrasts with high-income coun-tries,where weightfaltering is most attributedtohigher parity, low appetite, weaning/feeding/eating difficulties, or lack of positive interactions between infants and parents.26 This study also observed an inverse and

sig-nificant association between parityand CWG;however, it was not sustained after adjusting for the other factors. This may have occurred due tothe relationship between higherparity and lower incomeand educationallevels in Brazil.27

Although food insecurity and incomelevel are related variables,inthepresentanalysiseconomicstatusperformed betterasexplanatoryvariableofCWG.Theauthorsattribute thistothefactthatthequestionsintheEBIAarerelatedto anyeventoffoodinsecurityinthepastthreemonths, with-outconsidering thefrequencyofevents; furthermore,the processforafamilytoimprovetheireconomic statusmay requireconsiderabletime(evengenerations).TheCWGwas sensitivetosuchdifferenceand,therefore,itisreasonable toconsiderthatinfants wereexposedtothesameor sim-ilareconomicenvironmentdescribedatsurveysincebirth, considering that thoseliving in less privileged households experiencedpoorerpostnatalweightgaincomparedtothose fromwealthyfamilies.

The variation in the effect size and the level of asso-ciation between low maternal educationand CWG in the bivariate and multivariate analyses was noteworthy. The samerationaledescribedpreviouslycanbeusedtoexplain suchvariation,sinceeconomicstatusandeducationallevel arerelatedvariables.However,therewassome effecton CWGthatwasnotfullyexplainedbyeconomicstatus,and after addingthe occurrence of fever in the previous two weeks,thelevelofassociationbetweenlowmaternal edu-cationandpoorweightgainincreased.

Lack of maternal educationis a recognized risk factor for negative health outcomes28 and, in this context, this

resultwasinterpretedasthematernal inabilitytoprovide adequatecare,eitherduetotheinabilitytorecognizethe developmentofan infectious process,or delay inseeking health services. The impact on weight gain is a conse-quenceofincreasedenergyexpenditureandreducedfood intake, due to the anorectic effect of pro-inflammatory cytokinesonappetiteregulatoryhormones(i.e.leptin)and neuropeptides(i.e.neuropeptideY)duringtheacutephase response.29Consideringthefamily’ssocioeconomicstatusin

thisequation---thatis,livinginanunhealthyenvironment ---these infants mayhave experienced multiple infectious eventsduringtheirlives.

Finally,thepositiveassociationbetweenmaternalheight andchildweightgainshouldnotbeinterpretedsolelyasa consequenceofsharedgeneticcharacteristics,butalsoasa milieuofinadequatehealthandnutritionduringawoman’s childhood (compromising her growth and, consequently, reproductive organ size) and pregnancy (insufficient pro-vision of nutrients impairing intrauterine growth).3 This

relationshiphighlightstheimportanceofimprovingnotonly

infants’ butalso women’shealthand nutritionalstatusto breakthiscycle.

Using data from the ALSPAC cohort, Din et al.30

com-paredthepatternsofweightgainamongchildrenwhohad ‘‘early weight faltering’’ (< 5th percentile of weight gain at 8 weeks),‘‘late weight faltering’’(< 5th percentile of weight gain at 9 months), and a control group. Similarly tothe present study,theyobserveda positiveassociation betweenageandCWG.Thepatternofweightgainwas dif-ferentdependingonwhentheweightfalteringoccurred,but bytheageof13yearsthesechildrensubstantiallyrecovered weight;however,theirstandardizedmeanweightandheight wasstatisticallydifferentfromthecontrolgroup.

Such findings highlight the importance of preventing nutritionaldisordersduringthefirst1,000daysoflife---from conceptionto2yearsofage---becausedamagesthatoccurin thisperiodwillbereflectedinlong-termhealthandhuman capitaloutcomes.3

Themainstrengthsofthisstudyincludeitsbasisonthe most recent representative sample of the Brazilian popu-lation,designed andconductedby ateamof experienced researchers,whousedCWGtoevaluatechildren’sgrowth; thus,theseresultshavenotonlyinternalvalidity,butalso canbegeneralizedtoallBrazilianinfantsand,althoughthe PNDSdatesfrom2006/07,itisconsideredthatthefindings arestillvalid,sincenomajorpoliticalorstructuralchanges haveoccurredinBraziliansocietyinthelastseveralyears. However,anewPNDS isneeded toupdatethe knowledge about the current children’snutritional and health status inBrazil, allowingcomparisonswithprevious nationaland internationalhealthsurveys.

It is important to consider two limitations in the interpretation of this study. First, although the PNDS-2006/07 included slums in the household sample, it did notconsideredinstitutionalized(i.e.hospitalororphanage), homeless,orchildrenlivinginsettlements;second,the mor-tality bias,which is related tothedeath ofchildren who werebornunderinadequateconditionsorwereexposedto adverseconditionsduringthegestationalperiod.Therefore, thesefindingscannotbegeneralizedtochildrenlivingunder thedescribedcircumstances,andfurthermore,these limi-tationsmayhave underestimatedthemagnitudeandlevel ofassociationoftheresults.

Contrarytothe attainednutritionalstatus (i.e.,WAZ), theCWGisgenerated consideringthe birthweight,which allowsfortheanalysisofhowmuchachild deviatedfrom his/her expected weight gain, considering his/her peers, providingabettermeasureofenvironmentalinfluencesof growth.However,thisis ameasureexclusive toacademic research,andcannotfeasiblybeusedinaclinicalsetting.

WeightgainamongBrazilianinfants 291

Theseresultsshowedthatpovertyandlowerhuman capi-talarestillkeyfactorsassociatedwithpoorpostnatalweight gain. The approach used was sensitive in characterizing inequalities among different socioeconomic contexts and in identifying factors at different levels of determination associatedwithCWG.

Funding

The Brazilian Children’s and Women’s Demographic and

HealthSurvey2006/07wasfundedbytheMinistryofHealth andexecutedbytheBrazilianCenterforAnalysisand Plan-ning (CEBRAP).The authorJSreceiveda scholarshipfrom

Fundac¸ão de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo

(FAPESP)protocolno.2011/17736-4.TheauthorAPreceived ascholarshipfromCoordenac¸ãodeAperfeic¸oamentode Pes-soalde Nível Superior (CAPES). The authorJT is partially fundedbyConselhoNacionaldeDesenvolvimentoCientífico eTecnológico(CNPq).

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.World Health Organization. Physical status: the use and interpretationofanthropometry-reportofaWHOExpert Com-mittee.WHOTechnicalReportSeries:WHOLibrary;1995. 2.UnitedNationsChildren’s,Fund.,Strategyforimproved

nutri-tionofchildrenandwomenindeveloping,countries.NewYork: UNICEF;1990.

3.Martorell R, Zongrone A. Intergenerational influences on childgrowthand undernutrition. PaediatrPerinatEpidemiol. 2012;26:S302---14.

4.Victora CG,de Onis M,Hallal PC, Blossner M, ShrimptonR. Worldwidetimingofgrowthfaltering:revisitingimplicationsfor interventions.Pediatrics.2010;125:e473---80.

5.BlackRE,AllenLH,BhuttaZA,CaulfieldLE,deOnisM,Ezzati M,etal.Maternalandchildundernutrition:globalandregional exposuresandhealthconsequences.Lancet.2008;371:243---60. 6.VictoraCG,AdairL,FallC,HallalPC,MartorellR,RichterL, etal.Maternalandchildundernutrition:consequencesforadult healthandhumancapital.Lancet.2008;371:340---57.

7.Brasil,MinistériodaSaúde.PolíticaNacionaldeAlimentac¸ãoe Nutric¸ão.Brasília:MinistériodaSaúde;2012.

8.VictoraCG,AquinoEM,doCarmoLealM,MonteiroCA,Barros FC,SzwarcwaldCL.MaternalandchildhealthinBrazil:progress andchallenges.Lancet.2011;377:1863---76.

9.RamalingaswamiV.Newglobalperspectivesonovercoming mal-nutrition.AmJClinNutr.1995;61:259---63.

10.HeeringaSG,WestBT,BerglundPA.Appliedsurveydataanalysis. 1stedBocaRaton:ChapmanandHall/CRC;2010.

11.BerquóE,GarciaS,LagoT.Aspectosmetodológicos-Pesquisa NacionaldeDemografiaeSaúdedaCrianc¸aedaMulher---PNDS

2006.[cited04Apr2014].Availablefrom:http://bvsms.saude. gov.br/bvs/pnds/img/MetodologiaPNDS2006.pdf

12.WorldHealth,Organization.,WHO.,Child GrowthStandards: Length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: methods and, development. Geneva: The World Health Organization; 2006.

13.ColeTJ.Conditionalreferencechartstoassessweightgainin Britishinfants.ArchDisChild.1995;73:8---16.

14.ColeTJ.Presentinginformationongrowth distanceand con-ditionalvelocityinonechart:practicalissuesofchartdesign. StatMed.1998;17:2697---707.

15.Associac¸ão Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa (ABEP).

Critério de Classificac¸ão Econômica Brasil (CCEB). 2009.

[cited 04 Apr 2014]. Available from: http://www.abep.org/

novo/FileGenerate.ashx?id=251

16.Brasil,MinistériodaSaúde.PesquisaNacionaldeDemografiae

SaúdedaCrianc¸aedaMulher---PNDS2006:dimensõesdo

pro-cessoreprodutivoedasaúdedacrianc¸a.MinistériodaSáude:

Brasília, 2009. [cited04 Apr 2014]. Available from: http://

bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/pndscriancamulher.pdf 17.Kepple AW,Segall-CorreaAM.Conceptualizingandmeasuring

foodandnutritionsecurity.CienSaudeColet.2011;16:187---99. 18.VictoraCG,HuttlySR, FuchsSC,OlintoMT.Theroleof con-ceptualframeworksinepidemiologicalanalysis:ahierarchical approach.IntJEpidemiol.1997;26:224---7.

19.GardnerMJ,AltmanDG.ConfidenceintervalsratherthanP val-ues:estimationratherthanhypothesistesting.BrMedJ(Clin ResEd).1986;292:746---50.

20.BlackRE, Victora CG, WalkerSP, BhuttaZA, ChristianP, de Onis M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and over-weight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382:427---51.

21.Brito F.Thedisplacementof theBrazilianpopulation tothe metropolitanareas.EstudAv.2006;20:221---36.

22.CarterMA,DuboisL,TremblayMS,TaljaardM.Theinfluence ofplaceonweightgainduringearlychildhood:a population-based,longitudinalstudy.JUrbanHealth.2013;90:224---39. 23.SprayAL,EddyB,HippJA,IannottiL.Spatialanalysisof

under-nutritionofchildreninléogâneCommune.HaitiFoodNutrBull. 2013;34:444---61.

24.MelliLC,WaldmanEA.Temporaltrendsandinequalityin under-5mortalityfromdiarrhea.JPediatr(RioJ).2009;85:21---7. 25.VictoraCG.Diarrheamortality:whatcantheworldlearnfrom

Brazil?JPediatr(RioJ).2009;85:3---5.

26.ShieldsB,WacogneI,WrightCM.Weightfalteringandfailureto thriveininfancyandearlychildhood.BMJ.2012;345:e5931. 27.Huttly SRA, BarrosFC,Victora CG,Lombardi C,Vaughan JP.

Subsequentpregnancies:whohasthemandwhowantsthem? ObservationsfromanurbancenterinSouthernBrazil.RevSaude Publica.1990;24:212---6.

28.ChenY,LiH.Mother’seducationand childhealth:istherea nurturingeffect?JHealthEcon.2009;28:413---26.

29.ShilsME, Shike M,RossAC,CaballeroB,Cousins RJ.Modern nutritioninhealthanddisease.10thed.Baltimore:Lippincott

Williams&Wilkins;2005.