www.jped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Quality

of

life,

school

backpack

weight,

and

nonspecific

low

back

pain

in

children

and

adolescents

夽

Rosangela

B.

Macedo

a,

Manuel

J.

Coelho-e-Silva

a,

Nuno

F.

Sousa

b,

João

Valente-dos-Santos

a,c,

Aristides

M.

Machado-Rodrigues

a,

Sean

P.

Cumming

d,

Alessandra

V.

Lima

e,

Rui

S.

Gonc

¸alves

f,

Raul

A.

Martins

a,∗aUniversidadedeCoimbra,Coimbra,Portugal

bUniversidadedeSãoPaulo(USP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

cUniversidadeLusófonadeHumanidadeseTecnologias,Lisboa,Portugal dUniversityofBath,Bath,UnitedKingdom

eUniversidadeFederaldoAcre(UFAC),RioBranco,AC,Brazil fInstitutoPolitécnicodeCoimbra,Coimbra,Portugal

Received7February2014;accepted6August2014 Availableonline7February2015

KEYWORDS

Qualityoflife; Nonspecificlowback pain;

Childrenand adolescents; Schoolbackpack

Abstract

Objectives: Todescribethedegreeofdisability,anthropometricvariables,qualityoflife(QoL),

andschoolbackpackweightinboysandgirlsaged11-17years.ThedifferencesinQoLbetween

thosewhodidordidnotreportlowbackpain(LBP)werealsoanalyzed.

Methods: Eighty-sixgirls(13.9±1.9yearsofage)and63boys(13.7±1.7yearsofage)

par-ticipated.LBPwasassessedbyquestionnaire,anddisabilityusingtheRoland-MorrisDisability

Questionnaire.QoLwasassessedbythePediatricQualityofLifeInventory(PedsQL).Multivariate

analysesofvarianceandcovariancewereusedtoassessdifferencesbetweengroups.

Results: Girlsreported higherdisabilitythanboys (p=0.01), andlowerQoLinthe domains

ofphysical(p<0.001)andemotionalfunctioning(p<0.01),psychosocialhealth(p=0.02)and

physical healthsummary score (p<0.001), andonthe total PedsQLscore(p<0.01). School

backpackweight wassimilarinbothgenders(p=0.61)andinparticipantswithandwithout

LBP(p=0.15).Afteradjustments,participantswith LBPreportedlowerphysicalfunctioning

(p<0.01),influencinglowerphysicalhealthsummaryscore(p<0.01).

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:MacedoRB,Coelho-e-SilvaMJ,SousaNF,Valente-dos-SantosJ,Machado-RodriguesAM,CummingSP,etal. Qualityoflife,schoolbackpackweight,andnonspecificlowbackpaininchildrenandadolescents.JPediatr(RioJ).2015;91:263---9.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:raulmartins@fcdef.uc.pt(R.A.Martins).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2014.08.011

264 MacedoRBetal.

Conclusions: GirlshadhigherdisabilityandlowerQoLthanboysinthedomainsofphysicaland

emotionalfunctioning,psychosocialhealth,andphysicalhealthsummaryscores,andonthe

totalPedsQLscore;however,similarschoolbackpackweightwasreported.Participantswith

LBPrevealedlowerphysicalfunctioningandphysicalhealthsummaryscore,yethadsimilar

schoolbackpackweighttothosewithoutLBP.

©2015SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Qualidadedevida; Lombalgianão específica; Crianc¸ase adolescentes; Mochilaescolar

Qualidadedevida,pesodasmochilasescolareselombalgianãoespecíficaem crianc¸aseadolescentes

Resumo

Objetivos: Descrever ograu deincapacidade,variáveis antropométricas, qualidadedevida

(QV)epesodasmochilasescolaresemmeninosemeninascom11-17anosdeidade.Também

sãoanalisadasasdiferenc¸asnaQVentreosquerelataramounãolombalgia(LBP).

Métodos: 86 meninas (13,9±1,9 anos) e 63 meninos(13,7±1,7 anos) participaram.A LBP

foiavaliadaporumquestionárioeaincapacidadepeloQuestionárioRoland-Morris.AQVfoi

avaliadapeloQuestionárioPediátricosobreQualidadedeVida(PedsQL).Asanálisesdevariância

edecovariânciamultivariadasforamusadasparaavaliarasdiferenc¸asentreosgrupos.

Resultados: Asmeninasrelatarammaiorincapacidadequeosmeninos(p=0,01)emenorQVnos

domíniosdefuncionamentofísico(p<0,001)eemocional(p<0,01),noescoresumáriodesaúde

psicossocial(p=0,02)esaúdefísica(p<0,001)enoescoretotalnoPedsQL(p<0,01).Opesodas

mochilasescolareserasemelhanteparaambosossexos(p=0,61)eparaosparticipantescom

esemLBP(p=0,15).Apósajustes,osparticipantescomLBPrelatarammenorfuncionamento

físico(p<0,01),influenciandoummenorescoresumáriodesaúdefísica(p<0,01).

Conclusões: AsmeninastiverammaiorincapacidadeemenorQVqueosmeninosnosdomínios

defuncionamentofísicoeemocional,nosescoressumáriosdesaúdepsicossocialefísicaeno

escoretotalnoPedsQL;contudo,foirelatadoumpesosemelhantedasmochilasescolares.Os

participantescomLBPrevelarammenorfuncionamentofísicoeescoresumáriodesaúdefísica,

mesmocarregandomochilasescolaresdemesmopesoqueaquelessemLBP.

©2015SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Todososdireitos

reservados.

Introduction

Qualityoflife(QoL)takesintoaccountsubjective interpre-tationsandtheprocessin whicheachindividualcompares his current life with some identified criteria.1 Studies

investigating gender differences in QoL have produced

some equivocal results, with some reporting lower QoL2

infemales,whileothershavenotobservedanydifference

betweenmalesandfemales.3Accordingly,theeffectof

gen-deruponQoLremainsunclear.Thissubjectiveconceptcould

alsobe influencedby several health conditions, including

nonspecific low back pain (LBP).3 Among adults, LBP is a

commonsymptom,with7%to80%ofthepopulation

expe-riencingat leastoneepisodeintheir lifetime,and80% to

85%ofcasesareconsideredasnonspecificLBP.4Inchildren

andadolescents,theprevalenceofLBPisquitesimilarwith

thatobservedinadults.5Thus,theprevalenceofLBPin

chil-drenandadolescentsremainshigh,varyingbetween30-70%,

dependingonthepaindefinition,populationage,andtype

ofresearchdesignofthestudy.6

Health professionals and parents have highlighted the

regularwearingof backpacks,for the purposeof carrying

schoolmaterialsandsupplies,asapotentialriskfactorfor

LBPin children and adolescents.7 Despitethe absence of

reference-values for the weight of school backpacks, the

increasedloadisseenasanimportantfactorfavoringback

pain,8andmostresearchersandhealthpractitionersagree

withalimitfortheweightofabackpackwhichshouldnot

exceed 10% of the student’s body mass, and the weight

shouldbeequallydistributedacrossbothshoulders.8

Over 10% to 40% of adolescents have reported that

theirdailyactivitiesarebeingsomewhatlimitedbyLBP.9,10

Further research has revealed that LBP experienced in

childhood is associated with chronic LBP in adulthood.8

However,few studieshave specificallyusedvalidated and

standardizedinstrumentstoexaminetheLBPandits

poten-tial effect on QoL.11 Similarly, the overall health status

of adolescentswho usually report LBP is unknown and it

seemstobedifficulttodefinetheboundariesofanunique

experience,or the painasa health problem.7 The use of

standardizedQoLinstrumentsmaydisclosethehealthstatus

amongdifferent generalpopulations, individuals suffering

pain,andsubgroupsof childrenandadolescentsreporting

LBP.

Inthecontextofthesetrends,thepresentstudyaimed

todescribethedegree ofdisability,anthropometric

varia-bles,QoL,andschoolbackpackweightinboysandgirlsaged

differencesin QoLbetween children andadolescentswho

didordidnotreportLBP.

Methods

Studydesignandparticipants

The study had a cross-sectional design. The sample was recruitedfrom12classesintwoschoolsof thecityof Rio Branco,Brazil;a totalof324 studentswereinitially eligi-ble toparticipatein this study.However, only a groupof 149(86 femalesand63 males;age11-17 years)remained andagreedtotakepartintheinvestigation,after consider-ingtheinclusioncriterionasa‘yes’answertothefollowing question: ‘‘Duringthe last year,did youfeel anyepisode ofdiscomfortinthelowback,extendingtothelegs?’’.The exclusioncriteriacomprisedidiopathicscoliosis,spondylitis, andherniaofintervertebraldiscus.

All participants agreed to take part of this study and theirparents/guardiansprovidedwritteninformedconsent, consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods andproceduresofthisinvestigationwereapprovedbythe InstitutionalScientific Boardof theUniversityof Coimbra, Portugal.Clinicaldatawererecordedusingstructured ques-tionnaires, which were administered by trained research assistants.

Aftertherecruitmentperiod,participantswereinvited toapreliminarymeetinginwhichtheywereinformedabout thenature,benefits,andrisksof thestudy.Inthesecond part of this meeting, participants completed the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), and the Pediatric Quality of LifeInventory(PedsQL). Asecond meeting was thenscheduledfortheassessmentofanthropometric varia-bles.Theweightofeachparticipant’sschoolbackpackwas measuredonthreeseparatedayswithinaweekandthena meanvalueacrossallthreedayswascalculated.

LBP

ThepresenceofLBPinthepastmonthwasevaluatedwith thefollowingdirectquestionatthetimeoftheassessment: ‘‘Inthepastmonth,haveyouhadlowbackpainwhichlasted foronedayorlonger?’’.Incaseofapositiveresponse, par-ticipantswereinstructedtoindicatethesiteofpainusinga picture.11Participantswerealsoaskedtocompleteaversion

oftheRMDQwhichhadbeenadaptedandvalidated

specifi-callyfortheBrazilianpopulationbySardáJúnioretal.12The

RMDQisasimpleinstrumentconsistingof24questionswith

dichotomous responses (yes/no)and measures thedegree

ofdisabilityexperiencedbytheparticipant.Thefinalscore

ontheRMDQrepresentsthesumofpositiveanswers,with0

correspondingtoapersonwithoutanycomplaints,while24

correspondstoapersonwithveryseverelimitations.

Schobertest

ParticipantswerealsoaskedtocompletetheSchobertest, whichisusedtomeasurethemobilityofthelumbarspine, and was first described by Schober.13 The test is carried

out in standing position and in maximum forward trunk

flexion,keepingthekneesextended.Withtheparticipantin

theorthostaticposition,parallelhorizontallinesaredrawn

10cmaboveand5cmbelowthelumbosacraljunction.The

testwasconsiderednormalwhentherewasvariationofat

least5cmbetweenthemeasuresinorthostaticpositionand

trunkflexion.

Health-relatedqualityoflife(HRQoL)

TheHRQoLwasassessedbyaversionofthePedsQL14 that

wasadaptedandvalidated fortheBrazilian populationby

Klatchoianetal.15Thisquestionnairecanbeusedtoassess

HRQoL in healthy children and adolescents, and in those

withacuteand chronic health conditions, andconsists of

23itemscomprisingfourmultidimensionalscales:i)

physi-calfunctioning(eightitems);ii)emotionalfunctioning(five

items);iii) socialfunctioning (fiveitems);iv) school

func-tioning(five items).The fourmultidimensional scales are

grouped in three summary scores: i) psychosocial health

summaryscore(15items);ii)physicalhealthsummaryscore

(eightitems);iii)totalPedsQoLscore(23items).Itemsare

reverse scored and linearly transformed to a 0-100 scale

(0=100; 1=75; 2=50; 3=25; 4=0), so that higher scores

indicatebetterHRQoL.

Anthropometricsandschoolbackpackweight

Staturewasmeasuredto0.1cm,usingastandard stadiome-ter,withthe participants in theupright position, without shoes.Bodyweightwasmeasuredbarefootinlightclothing onacalibrateddigitalbalance-beamscale(FilizolaPL200, Filizola®,São Paulo, Brazil)withprecision to thenearest 100g.Bodymass index(BMI)wasdeterminedby calculat-ingtheratioofthebodymassinkgbystatureinm2.The

anthropometricmeasurementswereconductedinseparate rooms,toensuretheparticipants’privacy.Schoolbackpack weightwasmeasuredatthreeseparateoccasionsduringthe weekwiththesamedigitalscale(FilizolaPL200,Filizola®, SãoPaulo,Brazil).

Statisticalanalysis

266 MacedoRBetal.

effects, respectively. Translated into partial eta squared, valuesof 0.01, 0.06, and 0.14 were considered as small, moderate,andlargeeffects,respectively.

Results

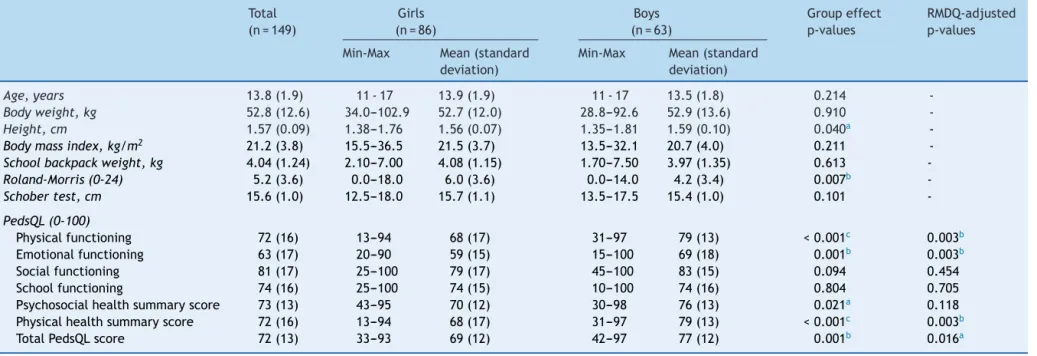

The characteristics of the participants are described in

Table 1. Both boys and girls aged between 11-17 years

reportedsimilarmeanvaluesforage(p=0.214).Mean

val-uesfor bodymass(p=0.910)andBMI(p=0.211)werealso

similarinboysandgirls,thoughboysweretallerthangirls

(1.59±0.10cmversus1.56±0.07cm).Compared toboys,

girlsreportedhigherlevelsofdisabilityasassessedbythe

RMDQ(p=0.007).GirlsalsoreportedlowerlevelsofHRQoL

thanboys,asmeasuredbythePedsQL,andalsointermsof

thedomainsof‘physicalfunctioning’(p=0.003),‘emotional

functioning’ (p=0.003), ‘physical health summary score’

(p=0.003),and‘totalPedsQLscore’(p=0.016).Theselower

scoresonHRQoLreportedbythegirlswereindependentof

degreeofdisability.

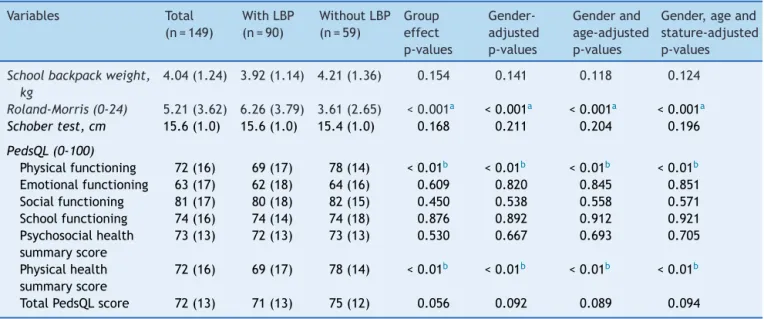

Table2highlightscomparisonsbetweenparticipantswith

LBPin thepast month (n=90; 55 girls and 35 boys),and

without LBP in the past month (n=59; 31 girls and 28

boys).ThemeanvalueforHRQoLwashigherinthose

with-outLBP(p<0.001),specificallyinthedomainsof‘physical

functioning’(p<0.01),and‘physicalhealthsummaryscore’

(p<0.01).The ‘totalPedsQLscore’ alsoshowedthesame

trendofdifferences,butwithamarginalvalue(p=0.056).

In participants with LBP, the lower HRQoL mean score is

similarafter controlling for potential confoundingeffects

ofgender,age,andstature.Nodifferenceswereobserved

betweenparticipantswithLBPandwithoutLBP,particularly

interms ofschool backpackweight, onthe Schobertest,

andinthePedsQLscalesof‘emotionalfunctioning’,‘social

functioning’,‘schoolfunctioning’,and‘psychosocialhealth

summaryscore’.

Discussion

Thisstudyaimedtodescribeandtocompare anthropomet-ricvariables,QoL,andschoolbackpackweightinboysand girlsaged11-17years,withandwithoutnon-specificLBPin thepast month. Boysweretallerthan thegirls (Table1),

whilethebodyweightandtheBMIweresimilarinbothboys

andgirls.Ofnote,differencesinstaturebetweengenders

increasefrom10yearsofage;16thisprocessisrelatedtothe

onsetofadolescence,whichhasbeenexplainedbyhormonal

influencesthataffectfemalesbeforemales.17Thepubertal

growthspurt thatoccurs laterand at greater intensity in

malesthaninfemalescontributestothehigherstatureand

bodyweightobservedinboysafterpuberty.18

The Schober test has been widely used by several

authors19 to assess the extent of lumbar flexion.

Consis-tent withprevious research,19 participants of the current

studywithLBPobtainedsimilarvaluesintheSchobertest

when compared with participants without LBP,

indepen-dently of gender, age, and stature (Table 2). However,

somestudieshavefoundincreasedmobilitytobeassociated

with decreased LBP.20 The majority of students obtained

more than 15 centimeters in the Schober test, which is

a positive performance. The lack of differences in that

test across groups could be associatedwith

methodologi-cal procedures (e.g., those assessments were conducted

duringphysical educationclasses).Consequently, students

mayhavealreadybeenengagedinactivity,and,thus,had

improvedtheirmusculartemperature19leadingto

enhance-mentsinflexibility. Infact,flexibilityhasalsobeenshown

to vary during the day, and differences in the time of

assessmentmayhaveinfluencedthecomparisonofresults

betweenstudentswithandwithoutLBPinthepresentstudy,

corroboratingresultsofpreviousstudies.21

Schoolbackpackswereregularlyusedbythemajorityof

studentswhoparticipatedinthecurrentstudy(99%);these

results areconsistent withlevels of useobserved by

oth-ersauthors.19Someauthors22havesuggestedthatincreasing

theweightoftheschoolbackpackisassociatedwithhigher

prevalenceofLBP,andtherefore,causingtemporaryor

per-manent postural maladaptation, muscle contracture, and

inflammation. Findings from the present study revealed

that128students(86%)hadatleastoneepisodeofLBPin

theirlives attributabletothedailytransportof the

back-packs, which is consistent with values reported in other

studies.9 At the moment of the evaluation, 60% of the

present participants (n=90) had reported LBP in the last

month, nevertheless all participants had experienced at

leastoneepisodeofdiscomfortinthelowbackduringthe

previousyear;however,nodifferenceswerefoundbetween

groups withand without LBP. Despite the fact that these

results are in line with some previous studies,9,23 others

have found associations between LBP and the weight of

theschoolbackpack,24particularlywhenasymmetrical

load-ingwasconsidered(carryingononlyoneshoulder), which

is associated with higher incidence of dorsal and lumbar

pain.25Infact,theabsenceofdifferencesbetween

partic-ipantswithandwithoutLBPinthepresentstudycouldbe

explained, at least in part, because only 18% of students

carry school backpacks on one shoulder, while 78% use it

bilaterally;theremaining4%of thestudentsusebagwith

wheelsandotherkindsofschoolbags.

Anothersource of variationis the timespent between

home and school, and the type of transportation. Prista

et al.26 observed thatLBP appears in home-school routes

longer than 30minutes. The majority of participants of

the present study (89%) usually travel by car between

home and school. The remaining 11% of students, who

usually go to school by walking, do it in a short time,

limitingthetimeofbearingweightontheback(34%walk

for less than15minutes;35%between 15-30minutes; 31%

over30minutes).Thiscertainly contributedtoexplainthe

lack of association between LBP and theschool backpack

weight.

Althoughthisstudydoesnotprovidesupportforbackpack

weightasriskfactorforshort-termLBP,itcouldnotexclude

itslong-termeffects.Infact,the long-termconsequences

of carrying heavy backpacks include discomfort and back

pain.27Therefore,Bauer&Freivalds28statethattheweight

ofthebackpackshouldnotexceed10%ofthebodyweight

and,therefore,couldpositivelycontributetoavoidfuture

healthproblems.Inthepresentstudy,themeanvaluesfor

backpacks weightwas4.04±1.24kg, andfor bodyweight

was52.8±12.6kg,whichfallswithinthelimits,and

proba-blyalsocontributestotheabsenceofsignificantdifferences

of

life,

school

backpack

weight,

and

nonspecific

low

back

pain

in

children

267

Table1 Participants’characteristicsanddifferencesbetweengenderscalculatedwithmultivariateanalysis,adjustedfortheRoland-MorrisDisabilityQuestionnaire(RMDQ).

Total

(n=149)

Girls

(n=86)

Boys

(n=63)

Groupeffect

p-values

RMDQ-adjusted p-values

Min-Max Mean(standard

deviation)

Min-Max Mean(standard

deviation)

Age,years 13.8(1.9) 11-17 13.9(1.9) 11-17 13.5(1.8) 0.214

-Bodyweight,kg 52.8(12.6) 34.0---102.9 52.7(12.0) 28.8---92.6 52.9(13.6) 0.910

-Height,cm 1.57(0.09) 1.38---1.76 1.56(0.07) 1.35---1.81 1.59(0.10) 0.040a

-Bodymassindex,kg/m2 21.2(3.8) 15.5---36.5 21.5(3.7) 13.5---32.1 20.7(4.0) 0.211

-Schoolbackpackweight,kg 4.04(1.24) 2.10---7.00 4.08(1.15) 1.70---7.50 3.97(1.35) 0.613

-Roland-Morris(0-24) 5.2(3.6) 0.0---18.0 6.0(3.6) 0.0---14.0 4.2(3.4) 0.007b

-Schobertest,cm 15.6(1.0) 12.5---18.0 15.7(1.1) 13.5---17.5 15.4(1.0) 0.101

-PedsQL(0-100)

Physicalfunctioning 72(16) 13---94 68(17) 31---97 79(13) <0.001c 0.003b

Emotionalfunctioning 63(17) 20---90 59(15) 15---100 69(18) 0.001b 0.003b

Socialfunctioning 81(17) 25---100 79(17) 45---100 83(15) 0.094 0.454

Schoolfunctioning 74(16) 25---100 74(15) 10---100 74(16) 0.804 0.705

Psychosocialhealthsummaryscore 73(13) 43---95 70(12) 30---98 76(13) 0.021a 0.118

Physicalhealthsummaryscore 72(16) 13---94 68(17) 31---97 79(13) <0.001c 0.003b

TotalPedsQLscore 72(13) 33---93 69(12) 42---97 77(12) 0.001b 0.016a

PedsQL,PediatricQualityofLifeInventory. a p<0.05.

b p<0.01. c p<0.001.

268 MacedoRBetal.

Table2 Multivariateanalysisbetweengroups,adjustedforgender,age,andstature.

Variables Total

(n=149)

WithLBP

(n=90)

WithoutLBP

(n=59)

Group effect p-values

Gender-adjusted p-values

Genderand

age-adjusted p-values

Gender,ageand

stature-adjusted p-values

Schoolbackpackweight, kg

4.04(1.24) 3.92(1.14) 4.21(1.36) 0.154 0.141 0.118 0.124

Roland-Morris(0-24) 5.21(3.62) 6.26(3.79) 3.61(2.65) <0.001a <0.001a <0.001a <0.001a

Schobertest,cm 15.6(1.0) 15.6(1.0) 15.4(1.0) 0.168 0.211 0.204 0.196

PedsQL(0-100)

Physicalfunctioning 72(16) 69(17) 78(14) <0.01b <0.01b <0.01b <0.01b

Emotionalfunctioning 63(17) 62(18) 64(16) 0.609 0.820 0.845 0.851

Socialfunctioning 81(17) 80(18) 82(15) 0.450 0.538 0.558 0.571

Schoolfunctioning 74(16) 74(14) 74(18) 0.876 0.892 0.912 0.921

Psychosocialhealth summaryscore

73(13) 72(13) 73(13) 0.530 0.667 0.693 0.705

Physicalhealth summaryscore

72(16) 69(17) 78(14) <0.01b <0.01b <0.01b <0.01b

TotalPedsQLscore 72(13) 71(13) 75(12) 0.056 0.092 0.089 0.094

PedsQL,PediatricQualityofLifeInventory. ap<0.001.

b p<0.01.

Significantdifferencesbetween-subjectseffects.

In the present study,girls reportedlower mean values for HRQoLthan boysin ‘physical functioning’, ‘emotional functioning’,‘psychosocialhealthsummary score’, ‘physi-calhealthsummaryscore’,and‘totalPedsQLscore’.After controlling for the degree of disability, those differences weremaintainedwithexceptionforthe‘psychosocialhealth summary score’(Table 1). The lower HRQoL exhibitedby

thegirlscouldbepartiallyexplainedthroughthedifferent

recreationalactivities; boys have more leisure time than

girls,whilefemaleadolescentsareprobablymorefocused

helpingtheir mothersin householdchores. Another

possi-bleexplanationis relatedtothe onsetof pubertyand its

associationstophysiquechanges;infact,femalesfacegreat

challenges,because,forexample,theonsetofmenstruation

causesfrequentcomplaints,previouslyobservedbyKolip.29

Furthermore,individualdifferencesinbiologicalmaturation

havebeenshowntoaccountfortheagerelateddeclinesin

HRQoLinUK adolescent females.30 The hormonal

fluctua-tionsthatoccurinteenage girlsmayfurthercontributeto

changesinpsychologicalwell-being.2

A person with symptoms of LBP is often partially and

temporarily diminished in the performance of everyday

activities,whichnegativelyimpactsQoL,andlegitimizesper

setheimportanceofquantifyingthesubsequentfunctional

disability.10 However, this is not a consensus with others

authors.11TheRMDQwasusedinthepresentstudytoassess

thedegreeoffunctionaldisability,revealing,asexpected,

higherdisabilityinthosewhoreferredLBP,independentlyof

thegender,age,andstature(Table2).Ofnote,participants

withLBPhadlower HRQoL,butonly in thedimensions of

‘physicalfunctioning’and‘physicalhealthsummaryscore’;

thesedifferencesweremaintainedaftercontrollingforthe

effectsofthegender,age,andstature.Thesefindings

high-lightthenegativeimpactoftheLBPonthephysicaldomain

oftheHRQoLinyouth.

Inthecurrentstudy,participantswithandwithout LBP

carried similar school backpack weight, which seems to

suggestthattheweightofthebackpacks,ifwithinthe

rec-ommendedvalues,isnotariskfactorforLBP.Inaddition,

findings suggest that girls have higher levelsof disability

than boys, and lower HRQoL, particularly in the domains

of physical and emotional functioning, which impacts the

totalHRQoLscore.Finally,thepresentstudysuggeststhat

participantswithLBPreportlowerperceivedHRQoL,

specif-icallyinthephysicalfunctioningdomain.Collectively,these

findingsareofimportance,especiallytoencourageparents

and teachers to be aware of risk factors associated with

LBP. Moreover, LBP tends to be of low intensity and

fre-quency,andadultsshouldbeawarethatchildrenshouldnot

beexposedtoexcessiveloadsarisingfromschoolsupplies,

tocontributetoabetterQoLduringyouth.

Inconclusion,girlsreportedhigherdisabilitylevels,and

lowerQoLin thedomainsofphysical andemotional

func-tioning,psychosocialhealthsummaryscore,physicalhealth

summary score,andin thetotalPedsQL score,comparing

withboys.Theschoolbackpackweightwassimilarinboth

genders,waswithintherecommendedvalues,andwas

unre-lated toLBP. After controlling for potential confounders,

participantswithLBPhavelowerHRQoL,specificallyinthe

domainsofphysical functioning,andlowerphysicalhealth

summaryscore.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgments

of Medicine, Department of Landscape Architecture and UrbanPlanning,CollegeofArchitecture3137TAMUCollege Station, Texas 77843-3137 USA, for the construction of a standardized instrument for HRQoLand permission for its useinthisstudy.

References

1.TrineMR.Physicalactivityandqualityoflife.In:RippeJM, edi-tor.Lifestylemedicine.Malden,MA:BlackwellScience;1999. p.989---97.

2.O’SullivanPB,BealesDJ,SmithAJ,StrakerLM.Lowbackpain in17yearoldshassubstantialimpactandrepresentsan impor-tantpublichealthdisorder:across-sectionalstudy.BMCPublic Health.2012;12:100.

3.Gold JI, Mahrer NE, Yee J, Palermo TM. Pain, fatigue, and health-relatedqualityoflifeinchildrenandadolescentswith chronicpain.ClinJPain.2009;25:407---12.

4.Burton AK, Balagué F, Cardon G, Eriksen HR, Henrotin Y, LahadA, et al. Chapter2. European guidelines for preven-tioninlowbackpain:November2004.EurSpineJ.2006;15: S136---68.

5.KjaerP,WedderkoppN,KorsholmL,deLeboeuf-YC.Prevalence andtrackingofbackpainfromchildhoodtoadolescence.BMC MusculoskeletDisord.2011;12:98.

6.JeffriesLJ,MilaneseSF,Grimmer-SomersKA.Epidemiologyof adolescentspinalpain:asystematicoverviewoftheresearch literature.Spine(PhilaPa1976).2007;32:2630---7.

7.Balagué F, Dudler J, Nordin M. Low-back pain in children. Lancet.2003;361:1403---4.

8.CottalordaJ1,BourelleS,GautheronV,KohlerR.Backpackand spinaldisease: myth or reality? RevChir Orthop Reparatrice ApparMot.2004;90:207---14.

9.WatsonKD,PapageorgiouAC,JonesGT,TaylorS,SymmonsDP, SilmanAJ,etal.Lowbackpaininschoolchildren:theroleof mechanicalandpsychosocialfactors.ArchDisChild.2003;88: 12---7.

10.Roth-Isigkeit A, Thyen U, Stöven H, Schwarzenberger J, Schmucker P.Pain among children and adolescents: restric-tionsindailylivingandtriggeringfactors.Pediatrics.2005;115: 152---62.

11.PelliséF,BalaguéF,RajmilL,CedraschiC,AguirreM,Fontecha CG,etal.Prevalenceoflowbackpainanditseffecton health-relatedqualityoflifeinadolescents.ArchPediatrAdolescMed. 2009;163:65---71.

12.SardáJúniorJJ,NicholasMK,PimentaCA,AsghariA,Thieme AL.Validac¸ãodoQuestionáriode IncapacidadeRolandMorris paradoremgeral.RevDor.2010;11:28---36.

13.Schober Von P.Lendenwirbelsäule und Kreuzschmerzen (The lumbarvertebralcolumnandbackache).MunchMed Wochen-schr.1937;84:336---8.

14.VarniJW,SeidM,KurtinPS.PedsQL4.0:reliabilityandvalidity ofthePediatricQuality ofLifeInventory version4.0generic

core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39:800---12.

15.KlatchoianDA,LenCA,TerreriMT,SilvaM,ItamotoC,Ciconelli RM,etal.QualityoflifeofchildrenandadolescentsfromSão Paulo:reliabilityandvalidityoftheBrazilianversionofthe Pedi-atricQualityofLifeInventoryversion4.0GenericCoreScales. JPediatr(RioJ).2008;84:308---15.

16.SilvaDA,PelegriniA,PetroskiEL,GayaAC.Comparisonbetween thegrowthofBrazilianchildrenandadolescentsandthe refer-ence growthcharts: datafrom a BrazilianProject. JPediatr (RioJ).2010;86:115---20.

17.WellsJC.Sexualdimorphism ofbodycomposition.BestPract ResClinEndocrinolMetab.2007;21:415---30.

18.Malina RM, BouchardC,Beunen G. Human growth.Selected aspectsofcurrentresearchonwell-nourishedchildrenAnnRev Anthropol.1988;17:187---219.

19.FeldmanDE, ShrierI, Rossignol M,Abenhaim L. Risk factors for thedevelopmentof lowbackpainin adolescence.AmJ Epidemiol.2001;154:30---6.

20.JonesMA,StrattonG,ReillyT,UnnithanVB.Biologicalrisk indi-catorsforrecurrentnon-specificlowbackpaininadolescents. BrJSportsMed.2005;39:137---40.

21.Adams MA. Biomechanics of back pain. Acupunct Med. 2004;22:178---88.

22.HeuscherZ, GilkeyDP,PeelJL,KennedyCA.Theassociation ofself-reported backpackuseand backpackweightwithlow backpainamongcollegestudents.JManipulativePhysiolTher. 2010;33:432---7.

23.Kaspiris A, Grivas TB, Zafiropoulou C, Vasiliadis E, Tsadira O. Nonspecific lowback painduring childhood: a retrospec-tiveepidemiologicalstudyof riskfactors.JClinRheumatol. 2010;16:55---60.

24.OzgülB,AkalanNE,KuchimovS,UygurF,TemelliY,PolatMG. Effectsofunilateralbackpackcarriageonbiomechanicsofgait in adolescents: a kinematicanalysis. ActaOrthop Traumatol Turc.2012;46:269---74.

25.KorovessisP,KoureasG,ZacharatosS,PapazisisZ.Backpacks, backpain,sagittalspinalcurvesand trunkalignment in ado-lescents: a logistic and multinomial logistic analysis. Spine (PhilaPa1976).2005;30:247---55.

26.PristaA, BalaguéF,NordinM,SkovronML.Low backpainin Mozambicanadolescents.EurSpineJ.2004;13:341---5. 27.AkdagB1,CavlakU,CimbizA,CamdevirenH.Determinationof

painintensityriskfactorsamongschoolchildrenwith nonspe-cificlowbackpain.MedSciMonit.2011;17:PH12---5.

28.BauerDH,FreivaldsA.Backpackloadlimitrecommendationfor middleschoolstudentsbasedonphysiologicaland psychophys-icalmeasurements.Work.2009;32:339---50.

29.KolipP.Genderdifferencesinhealthstatusduringadolescence: aremarkableshift.IntJAdolescMedHealth.2011;9:9---18. 30.CummingSP,GillisonFB,SherarLB.Biologicalmaturationasa