Credit Markets in Brazil: The Role of Judicial

Enforcement and Other Institutions

Armando Castelar Pinheiro

Célia Cabral

Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social

Departamento Econômico

Avenida Republica do Chile, 100/ 14° Andar

CEP:20139-900 - Rio de Janeiro - RJ

Tel.:(021) 277-6987

Endereço eletrônico :castelar@bndes.gov.br

Janeiro de 1999

199903 L518

P!EPGE CERES TD

f1

iiiiuiiiiセimi@

1000086835Credit Markets in BraziI: The Role of Judicial Enforcement and Other Institutions

11 - Introduction

Armando CasteIar Pinheiro 2

Célia Cabral 3

December 1998

2 - Size and Structure of Brazilian Credit

Markets

2.1 Size of credit markets and allocation of credit 2.2 Interest rates2.3 Defauh rates

3 -Recovering a loan: Which are creditors' altematives?

4 -Impact of Judicial Efliciency on Credit Markets: A cross-state analysis 4.1 - Credit Activity and Judicial Enforcement

at

State leveI4.2 - Assessing the Impact of Judicial Enforcement on the Size of Credit

Markets

5 - Ahemative Private and PublicArrangements to

Ensure Willingness to Pay5.1 Credit bureaus 5.2 Public banks 5.3 Peer pressure

6 - Final

Remarks

1 1bis paper was pn:pared as part of tbe rcseardl projec1 "InstibaimaI AmmgaDfllts to EDsure Willinfl'HSS to Pay in Finaocial MarIcds: A

CoqIanIlive Analysis of Latin America 8Dd Europe", canduáed in Bnzil by tbe Cadro de EIitudos de Râorma do Estado

(CERES!EPGFJFGV), intbe cxmlelIt oftbe Ima-American I>evcIopmcDt BIIII(s Nctwork ofRcseardi Caúrs. lhe.mbcrs would Iiketothaak Rodrigo Fuattes, Túlio Japelli anel Fabio Giambiagi fortheir COIIJIIImtS to earlier versims ofthepaper, Ericson C. Costa lIIld other CaJIral Bank

officials for providing aggregate data 011 aedit markets; and Oswaldo Aripino, Luiz Borges, Roberto Reis, Sérgio Werlang. Evandro Coura,

Aulânio Bamto and Hamihon Andrade for explainingruIes aadpraái<les in Bra7ilian aedit markds. 0bvi0usIy, tbeusual disdaims apply. 2 Head of the Economics Dq>artmeII1 of BNDES, Researcher at the Cemro de Estudos de Reforma do EsIado (CERESJEPGElFGV) and

Professor ofEconomics at lhe Federal Univasity ofRio de Janeiro.

3 Professor ofEconomics at the Univasidade Nova ofLisboa. 1bis research was done while visiting IMPA and CERESIEPGFJFGV.

---1 -

Introduction

Soood financiaI markets have Iong

been

recognized as essentiaI to foster economic development, nol: only for their role in mobilizing savings to finance investInent and production, but aIso for their contribution to economic efficiency through the seIection and monitoring of investment project:s.As

noted by Stiglitz (1994, p.23), «enforcing contracts; transferring, sharing and pooling

risks;

and recording transactions, [are] activities that make them [financiaI markets] the 'brain' of the entireeconomic system, the centrallocus of decision making".

As

important as they are, however, financial markets have foood little room to flourish in many Iow- and middle-income countries. Poor economic policy and market fàilure are usua1ly blamed for this (e.g., Fry 1982). Macroeconomic instability increases credit risk, while Iow and ooevenly distributed income reduces market size and increasesunit

costs. High risk and costs keep interest rates high, limiting the pool of viable projects and increasing default rates. By the same token, the shortage of well-trained labor and the high cost of information (poor accounting systems, high costs of computers and information teclmology in general, etc.) aIso reduce the abi1ity ofbanks to assess borrowers' abi1ity

to

pay back their loans.As

a consequence, very little credit flows to the private sector.4Recent

studies have suggested another explanatioo for the ooderdevelopment of financial markets indeveloping countries: institutional failure. lhe role of institutioos in fostering economic development has a loog traditioo (e.g., North 1990 and Olsat 1996), but the link through financial markets is a more recent ooe. It relies 00 the fact that secure contract rights are essentia1 for banks and similar

instÍtutioos

to

work as the "brain" ofthe economy. Shleifer and Vishny (1996) discuss how the lack of proper contract enforcement reduces debtors' willingnessto

pay and, as a consequence, creditors willingnessto

lendo La Portaet ai.

(1996) assembled a data set on the legal protection of investor's rights and 00 the enforcement of such rights in 49 countries. lhey fo1IDdthat

legal rules differ greatlyand systematicallyacross countries, which may be grouped according

to

the origin oftheir legal system. According to these authors, common law countries tend to protect investors considerably better than civilIaw countries (with the French civilIaw countries ranking1ast

in investor protection). lhe same pattem is observed in the analysis of law enforcement and the quality of accounting standards. La Portaet ai

(1997) extend this earlier workto

test whether less investor protectioo leads to inferioropportunities for

externaI

finance and thusto

smaller capital markets. Their resuhs confirm the hypothesis that a better legal E:Ilvironrnent(described

by both legal roles and the quality of their enforcement) leadsto

both a higher valued and a broader capital market. French civillaw tradition countries have the least developed capital markets.5Although much progress has

been

made in ooderstanding the importance of institutional failure in explaining creditors' oowillingness to financefirms

and individuaIs in less developed countries, the pertinent empirical1iterature still has an important shortcoming: it does nol: separate out theeffects

of legal protection, accounting standards and judicial enforcement. This paper tries to overcome this gapby analyzing the discrete effect of the qua1ity of judicial enforcement on the performance of credit

markets.

lhe importance of efficient judicial systems for the development of complex. inter-temporal transactioos such as those taking pIace in credit markets has

been

well emphasized in the 1iterature. North (1992, p. 8), for instance, notes that: «Indeed, the difficu1ty of creating a relatively impartial judicial system thatenforces

agreements

has been acriticaI

stwnbling block in the path of economic development. In the Westem world the evolution of courts, legal systems, and a relatively impartial system of judicial enforcement has pIayed a major role in permitting the development of a complex. system of contracting4 These styIi2lIId &ás are cxmsisld セ@ 1he faâ 1hat lIIOIIl LItin Americm COUIIIric:s, whidl bave a bislory of IU#I iDtIatian mel pRlII(]UIICId

CQOIlOIJÜç セL@ tcnd to bave 10wer volumes ofblok Qedà to the priwte S«tor than deveJoped md Asian c:ounIria (exdudiag India). In

w:aeral. they are a1so Icss cffi<:icat md cpcnle with hiFer iulerc:st ntes. Oille, セ@ a Iaqec histoJy of maaoec:oaomic stability, is lhe

セッイエィケ@ exaptim. See Table B.I in Appmd:ix B.

5 Latin Amcricm COIlIIIrics fare partiadarly bad in thcir aoalysis 50 lhe UDderdevelopmaJ1 of thcir aedit madtds is a1so consislaIl with the institutiooal failure u-gument. This argument is also appeaIing because it heJps to explain why some countries (sudJ as ArgaItina, Brazll md

that can extend over time and space, an essential requirement for economic specializatioo". Williamsoo (1995) in fact suggests that the quality of a judicial system may be indirectly assessed by the complexity of the economic transactioos it

is

able to support. 6 Clague et ali (1995) explore this dependency of financiai markets on third party enforcement and obtain a set of crass-country regressioos that suggest that countries with lower ratias of "cootract-intensive" mooeyto

GDP tendto

grow less.

In Brazil, previous

effOrts

to analyze the impact of the judiciary 00 the economy include Camargo(1996) and Pinheiro (1996, 1998). Camargo (1996)

shows

how the slowness and bias of laborcourts

end up hurting workers and favoring

informality.

Pinheiro (1996)reviews

the relevam1iterature

and develops a theoretical framework linking judicial system performance and economic growth. Pinheiro (1998) gauges how businessmen assess the quality of the Brazilian judicial system, ideutifies wbat they perceiveto

be the system'smain

problems, and measures the economiccosts

ofthe inefficiency ofthe judiciary in terms of 0U1put, investment and employment. This study coocludes that improving judicial efficiency may have a signifícant impact 00 growth and presents anecdotal evidence of how the inefficient enforcement ofloan contracts reduces the volume and increases the price ofcredito

The main objective ofthis paper

is

thento

empirically assess the impact of judicial enforcement 00 thedevelopment of credit markets. Two subsidiary objectives are (i)

to

describe credit markets and the legal and judicial institutioos protecting creditors in Brazil and (ü)to

present the institutioos that substitute for good judicial enforcement ofcredit

cootracts. fi has four sectioos, in additionto

this introductioo. Section 2 presents data on the size of credit markets, the allocation of credit across difterent types ofborrowers, and 00 interest and defauh rates. Sectioo 3 looks at the legal andjudicialinstitutions protecting creditors' rigbts. Section 4 examines cross-state difterences in the size of credit

market

and assesses the importance of judicial performance as an explanatioo for the observed differences. Section5

deseribes different ways devised to capewith

institutiooal failure in specificcredit

markets - i.e. the privare and publicarrangements,

or forms of govemance, in Williamson's terminology, createdto

overcome the problems created by judicial inefficiency. Sectioo 6 coocludes.2 - Size and Structure of Brazilian Credit Markets

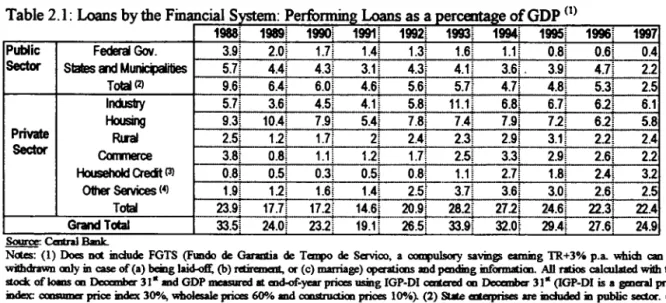

2.1 - Size of credit markets and aIloeatioo of credit

Brazilian financiai markets are characterized by a relatively low volume of credit,

higb

defauh rates and veryhigh

interest rates. Table 2.1 presents thestock

of performing loans provided by the domestic financiaI system at the eod of each year in 1988-97, broken down by typeof

borrower. fishows

that the total volume of creditis

oot ooly low but, somewhat swprisingly, ithas

comedown

as a perceotage of GDP since inflatioo was brougbtdown

in 1994. To some extent thiswas

the resuh of the cootractioo of banking creditto

the public sector, wbich accounted for 10.2% ofthe total in 1997, downftom 28.7 percent in 1988. This reduction resulted mainly from the cootraction in loans

to

thefederal

govemmeot and

is

largely explained by the process of privatizatioo: a large share of thecredits

extended

by banksto

the public sector consists ofloans to state eoterprises.In the privare sector, loans

to

housing and industry are individually the twomost

important segments,with 23.4% and 24.5% oftotal performing loans in 1997, respectively. But it

has

bem the consumercredit

segment thathas

posted the largestgrowth

rates since the launching of the 'Plano Real'. The dramatic reductioo in inflatioo rates after the 'PlanoReal'

(July 1994), from 2103.7% in 1993to

7.9«'10 in 1997 (lGP-DI), had as a resuh a signi5cant reductioo ofboth bank's ooo-interest income and overall uncertainty. These two factors encouraged and facilitated a substantial expansioo of creditto

the6 "'The upsh« is that lhe qua1ily of a judiciary cao be in&ned indireáJy: a ィゥセヲオイュ。ョ」・@ ecanomy (expressed in セ@ terms) wi1I supp<lIl more セ@ in lhe middIe ranse [i.e., Img-tam oodrading outside hicnrdúcal arpniDtians) tban wiU ao ecanomy wiIb a セ@ judic:iary. Pm diflêRuIly, in a law-paforlllMlCe eamomy lhe distribulim oftnnsac1ians will be more bimodaJ - wiIb sptt.-kct and hicnrdúcal transaáims anel fewer IJIicIdJH-msetransaáioos. "[Williamsan, 1995, p. 181-2)

private sector.7 This was especially the case of eredit to households, with consumer eredit increasing from. an average of 2.4% oftotalloans for the years 1998-1993, to 8.4% in 1994; it

has

since then further increased, having reached 13.0% in 1997.T bl 2 1

a e Loansb

y e mane thF'

ialS

SysteIn:P

e rmmg rfo . Loans as apef o fG DP (1)1988i 1989[ 1990i 1991 i QYYRセ@ QYYSセ@ 1994[ i995i i996i 1997

Public Federal Gov. 3.9t 2.0f 1.7 f 1.4t QNSセ@ 1.6t 1.( PNXセ@ PNVセ@ 0.4

Sector SlaIes lIId mセ@ 5.7[ TNTセ@ TNSセ@ 3.( 4.3[ 4.11 3.6t. SNYセ@ TNWセ@ 2.2

Total (2) 9.6t 6.41 VNPセ@ 4.6t UNVセ@ 5.7f TNWセ@ TNXセ@ UNSセ@ 2.5

InciJstry 5.7i 3.6i TNUセ@ 4.H 5.81 11.( 6.8t 6.7i 6.2i 6.1

Housing 9.3t QPNTセ@ 7.9i 5.41 7.81 7.4i 7.9i 7.2i 6.2i 5.8

Private RlIaI RNUセ@ 1.21 1.7t t 2.{ RNSセ@ 2.9t 3.1 セ@ 2.2[ 2.4

Sector Conmerce 3.8[ PNXセ@ 1.1[ 1.2[ 1.7 [ RNUセ@ 3.3[ 2.9t 2.6[ 2.2

HousehoId Qeát (3) 0.8[ 0.5[ 0.3[ 0.5[ 0.8[ 1.1 [ 2.7[ 1.8[ 2.4[ 3.2

Other Servic:es (C) 1.91 1.21 1.61 1.41 2.5i 3.7t 3.6i 3.0[ 2.6[ 2.5

Total 23.9i 17.71 QWNRQセ⦅@ 2O.9! 28.21 27.21 24.61 22.31 22.4

SSNUセ@ ;

Granel T atai 24.0 r 23.2! 19.1 i 26.5i 33.9í 32.01 29.41 27.6i 24.9

Source: CadraI Bmk.

Ncús: (1) Does n« inàude FGTS (FUIldo de Garantia de TCIq)O de Servico, a セuisoイy@ ウ。カゥョセ@ eaming TR+3% p.a. whid! can be wilhdrawn mJy in case of(a) being Jaid...ofI; (b) rdiremaJt, or (c) marriage) openticm lIIId pcnding informatim. AJ] ntios ca1aJlated wiIh the

stock oi Ioeas m Dccc:mba-31-and GDP DIC8SIIRd It cnd4year prices using IGP-DI anlcred m Dccc:mba-31-(lGP-DI is a gmcn1 price

iodex: CXlIISUIDI:I" price index 300/.., wboIesaIe prices 60% and CClIIStruáim prices 100.4). (2) Stáe cmrprises are iDduded in public seáor. (3)

IncIudes ali acdits to individuais Olha-thau. for bousinlf. (4) Indudes foundltims, institutes lIIId Olha-instilutioos maiotained wiIh budgctary

1imds from the public scctor (e.1f. autarquias).

The overall net publie debt, which is mostly contracted through securities rather than bank loans, varied substantially in 1981-97: from 23.7% ofGDP in 1981 to 50.1% ofGDP in 1985, decliningto 26.0% of GDP in 1994 and expanding again afterwards (fable 2.2). Even more significant is the variatiOll in the COmpoSitiOll of debt in its domestie and foreign compOllents. Net publie domestie debt, after more than

doubling as a percentage ofGDP in the eigbties, dropped as a resuh ofthe asset confiscation that took place in 1990-91, inereasing again after that, particularly since 1994. Net publie foreign debt, on the other hand, gained importance in the mid-eigbties, having falIen substantially since 1992

with

the accumulatiOll of foreign reserves. The other face of this process hasbeen

a substantial expansiOll in private foreign debt (mostly through bonds), which also belps to explain the contraction in domestie banking eredit as a proportion of GDP.Table 2.2: Net Publie Sector

Debt

(% ofGDP)n セ@ セ@ u セ@ セ@ セ@ a セ@ セ@ fl n セ@ セ@ セ@ % セ@

TOTAL Domestic . t püIic debt

Caatnl Gov. (iDcl. Cstnl

Ui

11.51 lU! 20.21 19.5! 16.2! 17.3l 19.7 [ 20.3! 15.51 12.01 17.0! 17.81 17.'1 21'Sl 27.0l 26.4 ..0.21 0.01 2.71 5.9[ 5.51 2.51 1.31 2.5t 6.8[ 0.4t -3.6[ ..0.61 0.9[ 3.0i 6.61 12.0i 12.5Bmk) セ@ セ@ セ@ セ@ セ@ セ@ セ@ セ@ セ@ セ@ セ@ セ@ セ@ セ@ f i

13.0 9.51 10.3i 11.1[ 5.li 4.9[ 3.9i 0.9

Sáde .... M-*ipaI Gcms. 3.3[ 4.3[ 4.8f 5.2i 4.91 4.71 5.21 5.2i 4.91 5.51 5.91 8.11 8.3i

セセセセセセセセKMセセセセKMセセセセセセセセセKMセセセセ@

State eaterprises 5.71 7.2i 9.1[ 9.li 9.Q 9.0[ 10.8i 12.0i 8.61 9.61 9.7i 9.5[ 8.61 FORip.t . . . . debt QTNYセ@ ャiloセ@ 32.9[ 33.2 i 3O.6i 28.7 i 3O.0i 25.8f llL6i 23.oi 23.3i lIL7í 14.4i

:::;-Gov.

(iDd.Ceatnl 4.41 5.9114.5113.6111.3113.21 16.3114.9111.5114.0114.5111.31 7.81 1L4[ 6.215.51 3.51

3.9! 4.3

1.61 1.9

Sáde ... MlIIIIdpIII Govts

セセMMセセセセセセセセセセセセセセセセセセセMMセセセセセ@

Sáde mt.erprises

0.9i 1.1

i

1.6! 1.8[ 2.li 1.8f 1.6[ IAl 0.9i I.I! l.°i 1.1 i l.°i 9.61 QQNPセ@ 16.8i 17.81 17.21 13.71 12.11 9.5t 6.21 7.9f 7.81 6.3i 5.6i0.3\ 0.3i 0.41 0.5 1.9

i

1.7[ 1.9j 1.9Source: CaJIraI Bank. These figpres do nOC inàudethe mmemy base.

A third motive forthe falI in the ratio ofbank eredit to GDP has

been

its substitution for other forms of eredit,with

the more widespread use of eredit cards, securities and direct eredit by retailers. Table 2.3 shows figures for creditcaro

companies. Following the sharp expansiOll of bousehold ereditwith

the'Real Plan', the number of credit cards and of transactions more than doubled from 1993 to 1997. Even more substantial was the increase in the value of transactiOllS, which more than doubled as a

7 McKinsey (1998) estimáes thIt from 1993 to 1995, tloIIt inoome dropped from 46 to 4 perQIIJl oi ova-aD bank inc:ome, wbereas nel inlecest inocme rase from 37 to 66 peraú ofthis total.

percentage of GDP. Similar results are observed for the stock of debentures, which are essentially issued by the private sector. There

was

a six-fold increase in the average stock, measured in USS,between 1993 and the 12 months ending in June 1998 (part ofthis increase was due to the appreciation ofthe real).

Table 2.3: Basic Statistics on Credit Canis and Debentures

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997

Credit Cards , , ,

ª

,

Number of Cards (thousand) 7903.1 7820.5 , 8431.5 , 11244.71 14369.3 , 17243.1 , 19384.8

nセッヲtセセHエィッセセ@ 105704.01151667.81199976.31210336.71319056.41437107.21516731.8

Value ofTransactions (% GDP) 1.29 1.32 i 1.48 セ@ 1.90 , 3.03 , , 3.29 3.47

Debentures: Stock at year end (% , 0.91 , 1.86 2.03 , 2.05 , 2.38

GDP) , , , ,

Source: ABECS and ANDIMA.

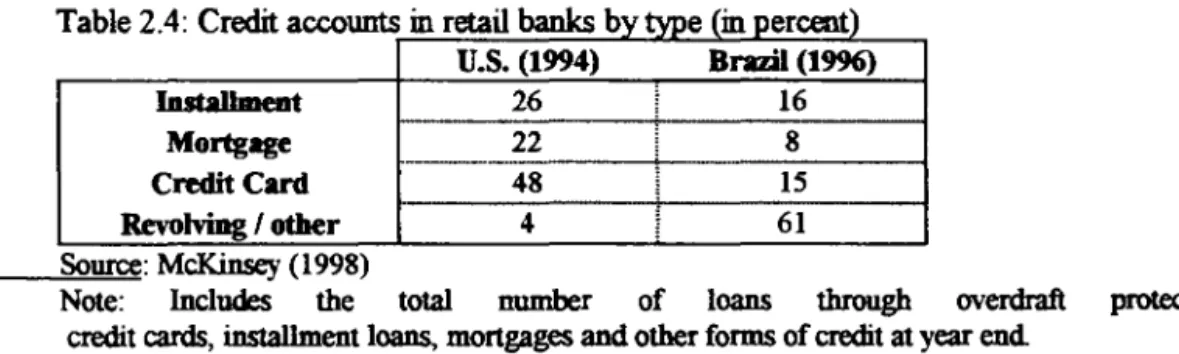

Despite

the substantial expansion in the number of credit cards and the volume of transactions, the proportion of these credit accounts in Brazilian retail banks remained much below that in the U.S. (fable 2.4), suggesting that there is still room for further expansion.Also

noteworthy is the much lower proportion ofmortgage accounts. In this way, retail banks coocentrate on short-term lending in the form of working capital, export finance, and credit for the acquisition of goods by firms and households, and on providing personalloans and overdraft facilities for firms and individuais. Table 2.5 preseots the stock of creditto

firms and households for typical short-term loan operations. Together, these ten types of short-term credit to firms amountedto

6. O and 5.7% of GDP at the end of 1996 and 1997, respectively. These figures are equal to roughly half ofthe total creditto

private industry, commerce and other services borrowers in each ofthe two years. The equivalent totaIs for households were 1.7 and 2.0 % of GDP, or about two-thirds of the total non-housing credit extended to household by the financiaI system in 1996 and 1997, respectively. In sum, most of the credit extended by retail banks, particularly private ones, is shorttermo

Table 2.4: Credit accounts in retail

banks

bytype (in percent)U.S. (1994) Brazil (1996)

InstaIImeDt 26 16

Mortgage 22 8

CreditCanI 48 15

RevoIviDg I otber 4 61

Source: McKinsey (1998)

Note: Includes the total number of loans through overdraft protection,

credit canis, installment loans, mortgages and other forms of credit at year end

The retail-banking sector shows a reIatively high coocentration: the three largest banks answer for 57% ofall deposits, against 13% ofthe next three largest and 30% ofthe remaining banks (fable 2.6). The sector is aIso characterized by a high participation of public banks, created

to

appropriate part of the tloating income and enable credit activities that would nol: tlourish naturaIly in a highly intlationary environment. State banks answer for about 60% of a11 deposits and assets and are responsible for virtually ali long-term credit, including aImost a11 credit for business investment and housing. Concerning the stock of credit, in 1997 publicbanks

answered for 52.1% of ali performing loans, private naticnal banks for 36.2% and foreign banks for the other 11.7%(a1though

this share increased substantially in 1998). In addition, we have that:[1] Public banks are responsible for aImost all lending

to

the public sector, federal and non-federal alike. Their loansto

the private sector have traditionally coocentrated on the housing, industry andruraI

sec:tors.

8 They have experienced a continuous but below average expansion in non-housing creditto

households since 1994, answering for 23.5% ofthis market segment in 1997.

[2] Private

national

banks are responsible for the remaining loansto

the public sector, but theserepresem

ooly a minor portion of their outstanding credits. Until 1993, private bankslem

preferably to industry, other services, housing and commerce, in this order. Since then, the importance of loansto

household has increased dramatically, while that of housing loans decreased. In 1997, private

national

banks answered for 55.3% of alI

credits

to households other than for housing.[3] The profile of foreign bank lending is even more concentrated. Until 1993, loans

to

industry, commerce and other servicescomprised

almost alI lending to the private sector. Sincethen,

the importance of loansto

households has increased very substantially, becoming second oo1yto

creditsto

industry. Lending to housing by foreign banks

was

negIigible throughout the 1988-97 period.Loans

to the public sector, relevant in the Iate eightieslearly nineties, have since then fàllento

almost zero. Table 2.5: Stock ofDifferent Kinds ofCreditto

Finns at End ofEach Year (% ofGDP)1996

1997

Credit to Finos

HotMoney 0.25 0.09

Discount

of

Duplicatas 0.40 0.41 Discount ofPromissory

Notes 0.07 0.07Working Capital 0.99 1.02

Overdraft Account 0.74 0.86

Credit for Acquisition

of Goods

0.10 0.12Vendor 0.54 0.47

Advances on Foreign Exchange Contracts 1.36 1.37

Export Notes 0.07 0.08

Resolution 63 nn-lons 1.47 1.24

Credit to Individuais

Overdraft Account 0.48 0.61

Personal Credit 0.38 0.65

Credit for Acquisition of

Goods

0.79 0.78 Source: CentralBank.

Table 2.6: Govemment Banks' Share ofDeposits and Concentration

ofR,.n1l-ino

Sector (199 6) (1)Country Private Banks Public Banks T<Jj)3 Top 4-6

Rest

Netherlands 100% 0% 77% 17% 6%

U.S. 100% 0% 10% 7% 83%

Korea 88% 12% 14% 9% 77%

Brazil 40% 60% 57% 13% 30%

Source: McKinsey (1998).

(1) Does not include interbank deposits.

3.2 -

Interest rates

Another reason for the low values of banking credit in Brazil is the very high real

interest

ratefaced

byfinns and households, a result

of

the high borrowing rate paid by banks and the high spreads theycharge.

The high passive rate is mainly a consequence of the over-reliance on tight monetary policy, which has substituted for a more effective fiscal policy since 1994. In 1994-97, the realinterest

rate onfederal

govemment securities averaged 21.5%p.a.As shown

in Table 2.7, banks paid similar rates on the certificates of deposit they issued in this period.On top ofthese

high

borrowing interest rates, banks charge large spreads. To some extent, these high spreads are the resuh of banks' low productivity that, despite having increased substantially since1991, is

still

much lower than in the U.S.A., Korea and the Netherlands. According to a study by McKinsey (1998), productivityis

particularly low in credit-granting activities:"Capital

intensity

and technology also cause productivity differences between Brazilian banks and best practice, principally in the credit processo The infancy of credit scoring models hinders productivity in granting loans to individuais and small business, whereonly

asmall

portion of applications

are

approved automatically. Thereis

also great intra-sector diversity. Wb.ile some banks have rather moderately advanced systems for credit-scoring others userudiment3ry

methods."onth) (2)

Table 2.7: Average Monthly

Interest

Rates

on Public and Private s・」オイゥエゥ・ウセ」・ョエ@ perm

Federal Bank

TR

TJLP InftatiOD (1) ExchangeGovern. Certificates

Rate

Securities ofDeposit DevaluatiOD

1990 23.45 26.1 n.a. n.a. 25.84 26.42 1991 16.68 17.69 n.a. n.a. 15.78 16.34 1992 26.31 26.21 23.49 n.a. 23.49 22.69 1993 33.34 32.81 31.15 n.a. 32.04 30.72 1994 23.46 19.75 23.37 n.a. 21.25 19.38

1995 3.61 3.5 2.32 1.77 1.16 1.09

1996 2.04 1.98 1.16 1.25 0.75 0.55

1997 1.86 1.88 0.76 0.81 0.60 0.6

Source: ANDIMA.

Nolt:8: (I) IGP-DI (2) The TR andtbe TJLP aretbe ÍIIlCnlSl rales1hat indexhousemortgages and developmeol bank Ioans, respec1ively. (3) n.a.: Not applicable.

A1though low productivity

is

a generalized problem in the Brazilian financiaI system, its importanceis

accentuated by the

high

proportion of activities carried out by public banks, which are more inefficientthan their private counterparts. For retail banks, Mckinsey (1998) estimates that labor productivity in state banks equals 29% ofthe average American bank and 56% ofthe average private Brazilian bank, concluding that:

"Govemment ownership reduces the overalllevel of productivity in two ways. Obviously, it

pulls down the sector's efficiency by employing halfthe sector's workers and achieving on1y half the productivity of private

banks.

Govemment banks aIso restrain efficiency improvements by lowering the leveI of domestic competitive intensity by creating a price-ceiling under which the more efficient banks can profitably and comfortably operate."High

interest ratesa1so explain

why most credit to the private sect.or goes to finance consumptioo andfirms' worlcing capital. Standard interest rates charged on short-term loans

are

presented in Table 2.8. These show that, 00 average,firms

pay lower interest rates than households. Still, annual interest rateson working capitalloans averaged 74% in 1995-97, against a mean annual inflation of 12%. Typical loans to households (other than for housing) are consumptioo and personal credit and overdraft accounts. Annual

interest

rates for these loans averaged 124.7%, 144.2% and 198.0% in 1995-97, respectively.Real interest rates for loans indexed to the exchange rate are much lower than those for loans in reais.

In

1995-97, advances 00 foreign exchange contracts (ACC) and Resolutioo 63 operations, the two mostpopular types of loans indexed to the dollar, had average annual

interest

rates of 20.3% and 31.8%, respectively, already including the exchange rate devaluatioo. Themain

reason why these ratesare

comparatively low

is

that banks get funding for these loans from borrowing abroad at rates much belowwhat they pay

domestically.

By indexing their loans to the exchange rate they transfer the exchange rate risk to borrowers. Inthis

way, the difference ininterest

rates between dollar and real denorninated loansarises

essentially from the cost to borrowers ofhedging against the devaluation ofthe real.The difference between interest rates charged on Resolution 63 and ACC operations is due

to

tbe 1atter's lower credit risk. There are two main reasons for that. First, while debtors in Resolution 63 operations are national finns or banks, in ACC loans tbe debtor is tbe importer buyÍIlg tbe goods exported. Second, tbe ACC loan is secured by tbe goods exported, which when tbe loan is granted havealready left tbe country. Therefore, in an ACC loan tbe creditor does not incur Brazil's country risk, neither from a macroeconomic nor from a judicial point of view. If he has to apply

to

the judiciary to recover tbe loan, he will do so in tbe importer' s home country.T a e bl 28

..

A verageMoothl

Iy Interest Rates on ort-Sh T ennLoans

Tak b en 'yF'

trmS an dIndividual

s.1994 1995 1996 1997 Credit

to

FarmsHotMoney 24.6 6.7 4.2 4.4

Discount of Duplicatas 24.9 8.0 5.4 4.7

Discount of Promissory Notes 27.1 8.5 6.0 4.8

Worlcing Capital 24.9 8.l 4.7 4.l

Overdraft Account 23.5 9.2 6.0 4.8

Credit for Acquisition of Goods 23.7 9.6 5.5 3.7

Vendor 26.2 5.5 3.1 2.7

Advances on ForeiBD

EX'"h ... --

Contracts

(1) 0.8 0.8 0.8 0.8Export

Notes (1) 1.7 1.6 1.3 1.2Resolution 63 Operations (1) 1.6 1.6 1.7 1.4

Credit

to

individuaisOverdraft Account 29.2 11.3 9.1 8.2

Personal Credit 26.9 9.8 7.l 6.3

Credit for Acquisition of Goods 27.3 9.7 6.6 4.7 Source: Central Bank.

Notes: (1) Plus exchange rate devaluation.

Interest rates are also much lower tban most oftbose in Table 2.8 in tbe cases of credits provided by development banks and of loans for housing. Development banks mance a large share of non-housing investment charging rates that vary from TJLP to TJLP plus 6% p.a.9

In

1995-97, tbe TJLP averaged16.4% p.a. They manage

to

charge tbese relatively low rates by having accessto

special sources of fundingat

compatible costs.In

tbe mortgage sector banks operate according to tbe following roles: [1] There are two systems. The first, called Sistema Financeiro da Habitação (SFH - Housing FinanciaISystem), is strictly regulated by tbe govemment, which sets caps on the value of tbe houses or apartments eligible for finance and on tbe value ofthe loans that may be extended.

In

tbe other system, called Carteira Hipotecária (Mortgage Portfolio), banks are free to set loan conditions.[2]

A!most

all

mancing for these loans comes from tbe popular savings accounts, which pay agovemmentally-fixed interest ofTR plus 6% p.a. and carry a government guarantee.

[3] By law, a large portion oftbe deposits in these savings accounts have to be used

to

provide housing loans in the SFH systemat

a fixed rate of TR plus 12% p.a.In

1995-97, this was equivalentto

an annual average interest rate of 32.5%. These are 15-year loans capped at RS 90,000 or 60% ofthe value ofthe property being bougbt (which may cost at most RS 180,000), whichever is lower.[4] Loans above these caps are available only in the Carteira Hipotecária system at a rate freely fixed

by banks, which in general range in the

interval

ofTR plus 14%to

16% p.a.Government regu1ation and the fact that tbese loans are secured by the property being financed at relatively higb co11aterallloan ratios explain why interest rates in tbe mortgage market are lower than tbose charged in the largely unsecured loans provided

to

firms and individuaIs. However, tbe9 The stcd. of1ooms by BNDES, Brui1's Nalicmal DeveJopment Bank. 8IIlOUIIted to 4.5% ofGDP lIl1he md of 1997.

continuous decline in the stock of housing loans in recent years, with most of the outstanding balances concentrated in public

banks

(see section 2.1), indicates that the situation is more complex thansuggested here. A possible explanation for these trends is the existence of laws blocking the repossession ofproperty in case of defauh ifthe col1ateral is the on1y house owned by the debtor. Further evidence on the importance of collateral

in

determining interest rates was obtained from a special survey carried outwith

banks in Brazil in the first semester of 1998.10 Banks reported that for personalloans annual rates ranged between 38 and 60% ifthere were 'real guarantees', between 38 and 90% for 'other guarantees', andbetween

75 and 269«'10 for lDlsecured lO3Os. Forfinn

loans, values were between 28.5% and 77.0% if there 'were guarantees (both kinds) and between 28.5 and 197% for lDlsecured loans.112.3 - Default rates

Another reason for the high interest rates in Brazil is the relatively high defauIt rate, which creditors factor in when

fixing

their spreads. Tables 2.9 and 2.10 present the stock of overdue and defauhed debts on December 31st forthe years 1988-97, measured as a proportion oftotalloans. As defined by the Central Bank, a debt is considered overdue if it has bem due for over 60 days.Loans

are COIlSidered defauhed if overdue for more than 180 days when guarantees are considered insufficient, or for more than 360 days when guarantees are considered sufficient.12lhe ratios of overdue and defauIt loans

to

totalloans averaged relatively high values in 1988-97: 2.6% and 18.8%, respectiveIy. In both cases, these averages have bem pushed by the high defauIt rates of the private sector. In fact, while recently the stock of non-perfonning Ioans (overdue pIus defauhed) to the public sector has declined, that of lO3Osto

the private sector has expanded very substantially, particularly since 1995. lhe pattems for overdue and defauhed loans have not, however, bem totally overlapping. For all types of private borrowers the ratio of overdueto

total lO3Os peaked in 1995, except for rural and housing loans, forwhich

the worse indicators were registered in 1990-94 and 1996, respectively. lhe proportion of overdue lO3Os declined in 1996-97 for industry, commerce, household and ct:ber services. On the other hand, the stock of defauhed loans has shown an almost continuous increasing trend for most types of private borrowers, ahhough for housing and rural credits the peaks were registered in 1996.What is pemaps more noteworthy is that the stock of non-performing debts at the end of 1997 swpassed that of peIfOllning lO3Os that, nonetheless, expanded during this período This appannt

paradox is explained by the high interest rates and large penahies levied on non-performing loans. A

survey

by ANEF AC (National Association of Factoring Firms) sbowed that banks chargemonthly

penahies that vary from 9.78%

to

16.00% (i.e., annualfees

of 206.4%to

493.6%) on the outstanding debt of overdue personal credits and overdraft accounts that exceed the allowed creditlimit.

13 In Table2.11 an attempt is made at netting out these two components from the stock of non-performing loans. As shown, at the end of 1997 the original stock of loans overdue and defauhed answered for just 8 percent ofthe total stock ofnon-performing loans. lhe defauIt rate, measured as the ratio of overdue

10 Thc:se rczuIIs peItÚl to a survey wiIh bmks regmtingthcir ardil pra<tices. The original セQ・@ oonsistcd of 44 bmks, ofwhidll8 rdUmed the qnectimn1ire. 8ince coe was 100 セャ、・@ to be usdW, aaly 17

_as

are induded in the malysis. The セi・@ ioduded oatiODaI md foreiJ!'1, Iarge and smaII. priwte and public baab, baseei m diffcraJ1 útes of Hrazil.11 Olha-quc:sIÍ<DS askcd about aedit guaraalees. For pcnmal aedit, 1IIISeCUIed ardil prevaiIs f<r smaD prMte bmks (wiIh me exaptiaoally

pn:faring 'uiha-セNIL@ whil .. moodium aod Iargr. baoks (publicmdpriYllÚ:)...mood lu pn:etn:illur GョZ。ャセG@ (Ihis WIIS Ih<: case

ar

4hanb) or 'cdIer guanntee5 HQィゥセ@ キ。Nセ@ 1he CL'Ie for arK'Jther 4 hanb). There doem 't -=rn to he a clear palll!m for hanb an 1h;" regard, however. aセ@

far 。Nセ@ finn aedit goe;, private hanhprefer 'dt\er guaranteeol' (with tmee exccptiOllll out ofthe 12 CII!Ie.'I), .... i1epublic hanh (exccpt ane) prefer 'real guaranters'.

12 The rq>arted"\-1IIues include ioterest and peoaIlies, calailaIed m ao aoaual basis. l.Jnder CaJIral DaDk reguIaticns, lIIISeCUI'ed aedits in 10cal

ammcy can rmWn in arrears f<r up to 60 days, partially secured aedits can rmWn in arrears for up to 180 days md fully secured aedb can remain in arrears for up to 360 days bc:fore being fUUy provisimcd. Upon beIloming 60 cIays in mars, partiaUy secured aedb must be

provisimed as to 50 percml ofthe recorded va1ue ofthe ardil JDd fWly secured aedirs must be provisiooed as to 20 percml ofthe recorded

valueoftheCRdit. Furtha-provisi<JIIiog is rcquircdto bemade t:Vt:ey 30 days1hcreaicr (up tothe 180· day or, asthe case may be, the 360" day)

to aJSUle tbat the provisian remains lIt the required levei of 50 percml or, as the case may be, 20 percml ofthe recorded vaJue oftbe 1oan. LoIDs

made by fmnciaI ioItiIutions to public seáor borrowcrs are traItcd in the same way as I<*IS to prMte seáor borrowcrs for this purpose.

13 In ヲ。セ@ a sut\IeY by lhe ccosuIling firm Austio Assis, wbidlmaiy7Jed tbe balance sheet of 25 banks in tbe fint semester of 1998, revealed tbat these bmksbad a profit ofRS 1.2 billioo wilhthese fees (in 'O Globo', August 23, 1998, p. 37).

plus defauJted loans to the total stock of extended loans, both net

of

income to appropriate,equaled

7.2 percent at the end of 1997.Table 2.9: Overdue

Loans

as a Percentage ofTotalLoans

fnP.r.P.mber SQセ@Public Seáor Private Sector Grand

Fedcnl States and TeUl Industry Housing Rural Commen:e Hous. Olha- Total Total

Gov. Municip. Credit Sa-vices

1988r-__ セPセNXセQ@ __ セUセNSセ|@ ____ WSNセUイM __ ャセNSセ|@ __ セPセNTセゥ@ __ セPセNXKQ@ __ セPセNVセQ@ __ セセセRGセZ@ __ セQNセQ|@ ____ セPNセXイM __ セQNセV|@

0.11 O.S\ 0.2\ 0.71 1.61 0.5 1.21

1989 4.01 2.6\ 3.0 I.Si

1990 17.91 2.4i 7.7 3.1 1 0.3 \ 6.31 1.1 1 1. 7! 1.31 1.9 3.41

1991 23.0! 12.51 16.1 3.01 0.21 8.0\ 1.3 i 1.2\ 1.71 2.4 5.91

1992 23.41 4.2i 9.4 2.61 0.41 6.41 1.31 2.41 1.3! 2.0 3.7!

1993 18.51 2.31 7.6 1.31 0.3\ 6.4\ 1.21 1.61 1.1! 1.5 2.S1

1994 19.8! 0.3! 6.0 3.11 0.5i 5.01 1.3\ Ui 1.2\ 2.0 2.51

1995 O.O! O.Sl 0.4 3.91 0.6\ 1.21 5.4\ 5.51 3.61 3.1 2.71

1996 O.O! 1.9! 1.7 1.4j 0.61 2.oi

1997 O.Ol 0.91 0.8 ui O.91 0.81 0.91 2.31 0.4[ 1.0 0.91

Source: Central Bank. Note: Loans are considere<! overdue if due for over 60 days (Central Bank Resolution 1748 of August 30, 1990). Values include interest and penalties. See other notes in Table 2.1.

Table 2.10:

DefauJted

Loans

as

a Percentage ofTotalLoans

lDerember 31 セ@Public Sector Private Seáor

Fedcnl States and TeUl Industry Housing Rural Commen:e Hous.

Gov. Municip. Credit

1988 0.6\ 0.9[ 0.8 5.91 1.4[ 2.0\ 35.81 1.8\

1989 1.91 1.8 6.01 1.0 [ 4.0[ 6O.71 1.6!

1990 9.7! 4.21 6.1 10.7[ 1.6[ 8.4[ 47.2\ 9.5[

1991 4.31 S.11 4.8 15.9! l.51 6.21 41.1\ 4.61

1992 8.S[ 12.81 11.6 I 1.9 [ 2.2i 10.ll 33.6\ 4.1\

1993 10.Sl 10.5 12.2l 2.3\ 21.1! 24.21 8.0\

1994 9.7[ 4.21 5.8 17.2! 2.71 20.41 21.1 i 5.91

1995 29.7[ 9.1 29.01 5.91 36.1! 26.7i 19.2\

Olha-Sa-vices 3.1\ 13.41 10.6\ 26.91 44.3 i 25.8\ 45.51

Grand

Total Total

10.5 7.8\

8.4 6.7\

11.0 9.7\

12.3 10.41

12.7 12.4\

18.0 16.8\

14.7 13.S\

26.8 24.5\

3.7 44.5

1

6.8i 32.31 37.9 33.4\1996 4.71 3.6i 4s.21 21.6[ 61 . NNLNNNTセャ@ ____ ... MMMMZBGセ@

1997 6.1[ 6.2! 6.2 61.Il 4.4i 27.8! 68.61 34.2 [ 80.81 55.7 53.21

Source: Central Bank. Note: Loans are considere<! defaulted if overdue for more tban 180 days and セエィ@ guarantees considered insufficient and for more than 360 days when guarantees are considere<! sufticient (Central Bank Resolution 1748 of August 30, 1990). Values are measured including interest and penalties. See other notes in Table 2.1.

Table 2.11: Total

Loans

ofthe Financiai System According to Payment Status(millioo

RS) (1)1995 1996 1997

(a) Perfol'lllina Ioans 209309 245846 255137

(b) Overdue Ioans 7529 5351 5430

(c) Defaulted Ioans 64814 107815 247634

(d) Overdue pJus defaulted Ioans 72343 113166 253064

e)=(a)+(d) Total 281652 359012 508201

(f) Income エッ。ーーセイゥ。エ・@ 43766 95607 233137

(g)=(e)-(f) Total Del of income to annmnriate 237886 263405 275064 (h)= (d)-(f) Overdue and defaulted loans oet of 28577 17559 19927

income to ... , ... riate

(i) = (h)/(g) Default rate 12.01% 6.67% 7.24%

Source: Central Bank.

Note: (1) These figures include FGTS and for this reason difIer somewbat from those reported in Tables 2.1, 2.9 and2.10.

Public

banks

have traditionallyshown

a higber ratio of overdue to total loans, with no clear ordering between national private and foreign banks (Table 2.12. See also Tables B.2 througb B.10 inAppendix

B for moredetailed

data). Since 1995, however, the differences among the threekinds

of

financiaI institutions have become less pronounced, virtually vanisbing in 1997. Public banks present a mucll higher ratio of overdue to total loans in the case of industry, rural, commerce and other servicesborrowers,

with

foreign banks in general faring better than private national banks in thesemarket

segments.

In the case ofhousehold credit, publicbanks

showed a worse perfonnance until1993,

but afterwards they had an above average success in reducing the proportion of overdue debts in this market segmento Concerning defauhed loans, we have that (see Appendix B):[1] Foreign

banks

present the lowest proportion of defaulted, although for themtoa

this

ratio increased substantially after1993.

Default rates measured in this fashion were particu1arly high in1995-97

for housing credits, in1994-95

for rural credits and household credit in1995.

They have also registered high volumes of defauhed loanswith

the federal public sector since1992.

[2]

Private nationalbanks

registered a high ratio of defauhed to performing loans throughout the1988-97

período These default rates havebeen

historically high for rural, commerce andother services,

and more recently for households. Default rates are low for housing and moderate for loans to industry.[3]

Most defau1ted loans in1997

wereconcentrated

on public banks. For them, the ratio of defau1ted toperforming loans increased substantially for all types of private borrowers, except for housing loans, for which the rise in this indicator was less significant. Interesting1y, in

1988-97,

the proportion of defaulted loans to the public sector was consistently lower in the case of public banks than in that of national private and foreign banks.Table

2.12:

Overdue and Defauhed Loans as a Proportion ofTotal Loans for Public, National Private and Foreign Financiai Institutions (in percent, December SQセ@Public Natrional Private Foreign Overdue Defauhed Overdue Defauhed Overdue

Defaulted

1988

2.1

2.1

0.8

18.1

0.6

0.6

1989

1.2

2.3

1.1

17.5

1.4

1.3

1990

4.6

6.8

1.3

16.4

3.6

2.8

1991

8.9

9.2

0.8

14.3

3.3

3.4

1992

5.6

11.6

0.6

15.5

0.8

4.7

1993

4.2

23.5

0.7

13.5

0.3

0.9

1994

3.9

13.6

0.8

14.4

1.1

4.9

1995

2.8

27.6

2.7

21.9

2.0

8.2

1996

1.3

44.0

2.0

13.2

1.3

8.7

1997

0.7

66.8

1.5

16.8

1.9

9.6

Source: Central

Bank.

3 - Recovering a loan: Which are creditor's a1tematives?

When a debtor defaults, the first stage of collection is usually an amicable one, usually carried out directly by the manager of the branch that

extended

the loan. If collection is not successful at this stage, the account is cIassifi.ed under ''loans in liquidation" and the contract issent

to thecredit

recovery department

ofthe bank.14 Formally, extra-judicial collection starts atthis

point. This is the preferred method of debt collection in Brazil - it is fast and avoids new expenses such as court and lawyerfees.

Moreover, it avoids increasing the antagonism between the bank and its client. Non-performing debtors face heavy penalties, induding 1argefees

charged by collection firms. Thesefees,

combinedwith

the high rates ofinterest, quickly cause the debt to "mushroom" (as described in section 2).As

a consequence, debt negotiations usually take place with largediscounts.

It is not uncommon for banks to dose deals accepting repayment of a mere40%

of the outstanding debt (which may still involve a larger debtor payment than the value ofthe originalloan).IS14 Crcdit ROCO\'a)' is usua1ly punued by baoks' I)qlutmmt of Crcdit, nther tban by thár Legall)qlartmcuL

1 S Public baoks may nd, by law, aazpt a deaI tbat n:tums less tban tbc originaIloan.

If extra-judicial collection fails, creditors may choose

to

take the caseto

court. Brazilian law allows judicial debt collection to be carried out in a few different ways.I6 lhe choice ofthe best procedure to follow depeods on the type of credit instrument used and on the formalities required by the legislation. lhe legal action least used by banks, dueto

its duration, is the ordinary action.This

action startswith

a cognizance action, in which the plaintifftries

to

establish that a debt of a giveo valueexists

and thatit is due. After an action ofthis type is initiated, the defendant has 15 days

to

respondo Ifthere is no response, the debt will be considered executable, meaning thatit

is liquid,certain.

and due. I7 However, ifthe judge is not convinced ofthe existence or ofthe stated amount ofthedebt,

or that it has matured, a judicial process isstarted, and only after the publication of a favorable court ruling can thedebt

beconsidered liquid, certain and due, and thus executable.

Only after the

debt

is considered executable may the creditar proceed to the next step: initiate another judicial process, ca11ed an execution action, in which he demands before a judge that the debtor pay bis debt. In the execution action, the defendant is asked to pay the debtwithin

24 hours orto

name assetsto

be held before the court as a guarantee ofpayment (this isknown

as the penhora ofthe assets).I8 If the debtor does not pay nor does he name the assets for the penhora within 24 hours, the court officerhimself

lists as many assets for the penhora as he considers necessaryto

satisfy the credito If the court officer does not find any assetsto

include in the penhora, it is up to the creditarto

search

for such assets andto

indicate themto

the COurt. I9 lhe execution action is suspended until such assets arefound. Assets included in the penhora may not be disposed of without the judge's pennission. Only after the penhora is completed can the case then be judged.

lherefore, a1though from a legal point of view there is not much difference between a

secured

and anunsecured

loan (in both cases the creditor must go through the motions described here), the existence of areal

guarantee insures that there will be assets for the penhora. If the loan has a persooaI guarantee, the assets ofthe guarantor will be available for the penhora ifthe debtorhimself

does

not have enough ofthem.20 If a finn enters into a concordata procedure (reorganization, see below), a secured creditardoes not need to go through the habilitation process for having the asset that serves as coIIateral

to

beincluded in the penhora; this happens automatically. In the case of baokruptcy, the creditar is paid once the asset is sold and, ifthere is any value left over, it is

distributed among

unsecured creditors.21 InAppendix

C we discuss the main types of guarantees used in credit contracts in Brazil.Ifthe debtor wants

to

defendhimself,

he will not do so within the execution action, but through another judicial actiao ca11ed an embargo to lhe execution action, which will be appended to the executionaction. Typical embargoes argue that interest rates are too

high,n

or that an asset may not be used inthe penhora because it is essential for the firm

to

operate and eventuaIly pay back the debt.23 lheembargo may also contest the use of compound interest (anatocismo), which is seen by many judges as

16 1be maio 1aw guidingjudicial ooIlec:tian of deUs is the Code ofCivil Process (Código de Processo Civil), Feda-al

r..w

5869 of JIIIIUU)' 11, 1971, in partiaJlar articles 566 to 795.17 A ddlt is 1iquid when there is DO doubt about the amounl thaI. bas to be paid by the debtor. Il is oertain if it bas bem structured aooording to the 1aw (c.g., a acdit aDrad bas to be セ・ウウ」、@ by MO people otbcr thao the aeditor and the debtor, who aIso bave to sigp the aDrad). Il is

due ifthe date ofpaymml bas passai..

18 Penhora cmsists ofthe attaduueIIl ofpropcrty in satisfadim ofa Iim.

19 In this search, the a-editor may work with thetax autbodics, thetelcphone セケL@ the dcpartmcot oflllOtQl" vàIides, etc. It shou1d be n<úd that, while in the cogtrizance action there is the possibilily of defen.se (with lhe judge coming to 1eam ofthe defen.se's a1Iepicms), in the

execJáion action the debtor may ooIy defmd himseIf afta-the penhora ofthe assets that guararáee paymml ofthe deIL ODe shou1d however

maIlicn that in most imtanccs the debtor's home c:aon« be included in the Iistcd assets.

20 h lIBISl be n<úd thaI. the a-editor may n«

sem.

the guaraPtee in case of defauIt. lbe guaraPtee only saves to fac:iJPte the process of obtainingassds forthe penhora. 1be

semue

ofthe guanntee itself is a1Iowed ooIy in lWo cases: (1) thá of a real estale mortgage (as in case of a housing Ioan) -theprocedurethm is the ClIIXÚioD ofthelllOdpge; and (2)the case ofaedit opentioos secured by fidoàary aIimIbD. forwhidl the a-editor may rapS a seardI melsemue

セ@ ofthe assel gjvm in guanaee.21 lfthe value raised by the sale is n« sufficiaJt to pay the aeditor back, he sbould thm habililale himseIf for the diffenDOe n« oovered, DOW as ao UDSeaJrCd a-editor, in the bmkruptcyprocedure.

22 Mo!;t <XIIIrIK:!s do n« specify a fixed iIUrest rale, but rather coe ofthe meRllce rales desaibed in seàim 2, in addition to a spread. In some

acdit opcraticns it is Dot unoommon to md up witb mcntbly real rales above 10 pcI"QCIJt. Debtors in mmy of these cases argue thaI. thcse are unreasonabIe and UDfair ntcs.

23 Job Ioss is anotbcr argIIIIIGIl to whidt many judgt:s are sensitive.

illegal.24 There have also beeo cases in which the debtor argues that the person who signed the contract

was nOl: authoriz.ed to do so.

Ifthe penhora ofthe assets took place and ifthe debtor has still nOl: paid nor has he managed to get bis

embargo accepted by the judge, then the assets are publicly auctioned. The proceeds of this auction are

then used

to

pay the debt (and the auctioneer's fees),with

the revenues exceeding the value of debt being retumedto

the debtor. Ifthere are no interested parties in acquiring the assets in the auctioo, the assets may then be transferredto

the creditar.Some credit securities are ruled by specific legislatioo that, if correctly used, guarantees that the securities satisfy the liquidity and certainty requirements. If a loan based on such securities is nOl: paid when due, the first step CODSists of notifying the public registry (Cartório de Oficio de Registro e

Protesto de Títulos) that the debtor has nOl: paid. This step is

known

as the protest ofthe security, orprotesto.25 lhe creditor can then proceed directly

to

an execution action. For this reason, thesesecurities are called self-executable.26 An execution action may thus have as object either (i) an

executive extra-judicial security, (i.e. the document received by the creditor - such as those

1isted

above) or (ü) a judicial executive title (the ruling proffered by the judge at the end of a successful

cognizance action).

Banks

usually struct.ure loans using self-executable credit securities, since they allow a much faster judicial collection in case of defauh.27 For this reason, banks onlyinitiate

a cognizance action in case that, due to an error or to legal impediments, the loan contractdoes

not have the requirements of an extra-judicial title, but yet there is evidence that the debt exists. An example is the case of current account debts (overdraft), in which there is no written contract except for the ooe opening the current account.28Judicial debt collectioo depends crucially 00 the debtor having sufficient assets to cover payment ofthe

debt. For this reason, banks usually demand their clients

to 1ist

their assets when q>eDing a current or credit account, an infonnatioo that is sometimes checked directly by the bank. It may be the case, though, that after contracting the loan the debtor sells bis or her property, making it no longer availableto

be put up for penhora - that is, the debtor becomes insolvent before the debt is due. In this case, the creditor may start a Pauliana action, showing the insolvency and bad faith ofthe debtor and seeking a court ruling canceling the relevant sales.29 Ifthe decisioo is favorable, the asset may beused

for the24 1bis idaprctalion fo\lows from articJe 192 of the Constitution, wbid1, however, has 11« yet been regulated and for this reason is 11« applicable, acc>ording to oIhers.

25 The protaro must take p1ace during a catain period oftime afta-1he debt is due. After 1bal, tbese sewrities 100se their property of being

seIf-executabIe and may serve onIy as proof of debt ia an ordinary action.

26 The セ@ of using seIf-execulable (or exlr2-juclicial) securities becomes eviderll by ncticing that the most oommanJy used credit

seaniIies in Brazil are seIf-execulab1e: lhe duphClJ1a (a catified and negotiable oopy of ao iavoia:, a acdit sccurày apparaIlIy cmtcm onIy in Brazil)., lhe biU of exmangc, lhe promissory DOte, and industrial and <XlIDIIQ"CÍaI acdit cédulas. EadJ is ruIcd by specifi<: 1egisJ3bon: Law S475 (.JuIy 18, 1968)forduphClJ1as, Deaee2044 (December 31,1908) forbills ofexàtange 。ョ、ーイッュゥウウッイケョセ@ and Deaeo-Law 413 (January9, 1969) and Law 6840 (M.aràt 11, 1980) for incIwúial and commerciaI aedit cédulas. A àteck (Law 7357 of Sq!tanber 2, 1985) is aIso seIf-executable. Some ofthe bank lswyas we inlerviewed poinled out, however, 1h8t lhe IerPlllion has ョセ@ kept up wiIh teàtno1ogj<:al àtlllge. For

セi・L@ for a duplicata to be seIf-exccutable, it must be signed by lhe diaJt wbo buys the good or scrvioethat originated il In pradioe, howewr,

gjven 1he large number of dcx:uments issued dai1y, banks no longa- process lhe doe paperwort. Dor do lhey àteck signllures. Banks siqlly

provide specific software to diEots, whEnl lhe basic informatjon on lhe duphcatas is recorded. The law, however, !till requins writtm dommmt ..

27 A standard cognizance action in Brazil may take sevenl years. This is the main reason wby cnditors avoid folIowing 1his type ofproceclure. Some lawya-s, however, point.ed out tbat beginning wiIh 111 execaúion action c:anies the ris/( of having lhe Iiquidity or catady of lhe dcbt questioned fiD1h« em in lhe case and, if 11« sufIicieDtIy estab1ished, lhe case has to be ratarted wiIh a cognizance action. lfthis happms, aIllhe

time and oosts inaJrred until1h8t point would have bem wasted. In sevenl cases, thcnfore, it wouJd be lcss risky to start wiIh lhe cognizance

action. An a1temaliveistostartwithamonitóriaaction("aSUJmDODStoappearbefore1heoourt..}.1bis action aIlows lhe debtor to pay bis dcbt

immediltdy, or to presaIl bis defcme. lflhe judge 8QtlCPls bis aIlegllions. lhe aáion beoomes 111 ordinary action. 01hawise, the deIlt becomes 1iquid, ccrtain and duc, a110wing iIs c:lIICICUtim.

28 An inlerestiDg procedure adcpced by banks anel aedit card セ@ when gjving appUlD\y uasecured persmaI c::rediI. suàt as owrdra1l aIlow-, is to iocIude a provisian in lhe canIraá aIlowing thcm to issue a credit sec:urily (e.g., a promisscry nde) agúnst lhe debtor in lhe amouol oflhe aedit <XlIlCClded. This sec:urily would tha! be sold in lhe market and used to ClOIIIpGIS8le 1he bank or aaIil card セケN@ In recem years, however, it has bem the ÍIIlaprdJIion oflhe judiciary that suàt procedure is illegal, because it disrespeás the CaJsumer Protectiem Law, lhat stIII.es that nobody may be asbd to sigp a blank CCDIraI1

29 N<ú tbat this is djjfermt fiom defrmuJing lhe execaúion, whidl bappals when lhe debtor seUs property after debt oo1Iedion has started (11« necessarily 1hrou1!lt lhe judicial systan). lhe fraud to execWon may be iDfonned in the execaúion action itseH; it is ョセ@ necasary to begin a new

penhora. The party who bought the asset in good

faith

may then sue the debtor.Banks

very rarely engage in this type of action doe to the difticuhy in proving the debtor's intentions when selling bis or her property.Under certain conditions, the creditor may try to judicially colIect a debt by requesting that the debtor is decIared bankrupt. Banks rarely folIow this route. Bankruptcy legisIatioo. gives preference to

debts

with workers and tax authorities.30 In practice, however, neither group tends to start a bankruptcy

actioo., since workers want to protect their jobs, and tax authorities are overwhelmed by inertia and by a large number oftax evasion

cases.

3I h is usualIy only after the finn stops paying suppliers and banks(usually the last to suffer default) that there may be parties

interested

in requesting debtorbankruptcy.

However, the incentives to do 50 are nal: stroo.g. In general, when a bank or supplier succeeds in a bankruptcy actioo., the little that is left over after paying for Iawyers and for court

fees

is barely enoughto pay workers and the govemrnent, let alane pay other debts. For this

reasoo.,

its does nal: make sense for them to request that the finn be declaredbankrupt.

Threatenin.g the firm with a bankruptcy Iawsuit in order to get repayment an a loan may nal: work either. Lawyers haveremarked

that if the court is alerted that the request forbankruptcy

isintended

only to pressure the finn to pay the loan, it will notgrant the request if the debtor shows that it is nal: "broke". If this happens, the bank will have to pay for Iawyer

fees,

judicial costs, etc.Even

ifthe request is granted, the bank will have to wait its tum toreceive whatever money is left after other preferred creditars are repaid. So in general banks prefer to

help the debtor to get out of difticuIties, often trading part of the debt for real assets at a substantial discount.

When a finn is declared bankrupt, alI execution actions are

haJted,

except for the fiscal executions. The judge then nominates a síndico (usually the largest creditar) who will manage the company, analyze thequality of its assets and liabilities and asses whether bankruptcy crimes have taken pIace. Once this process is conclude, the company is put either in (suspensive) concordata (500 below), in which case

management

retums to its owner(s), or in liquidation. Liquidation is a process in whichalI

the assets of thebankrupt

company are colIected, 50ld at a judicial auctioo., and used to pay back its creditors (according to the qua1ity ofthe credit, and proportianately for credits ofthe same qua1ity).If a debtor finds himselfto be financially insolvent, he may

ask

a judge to let him go into concordata. 32A concordata does not

affect

the debts the finn has with its employees, the tax authorities, creditssecured by real guarantees, and privileged credits (e.g., those that use cédulas de crédito). In fact, it

basically suspends paymeots to unsecured creditors. These are the creditors that usually provide the finn's working

capital

such asbanks

and suppliers. Although the law technicallyalIows

creditars toparticipate in the finn's reorganization process, it is

almost

impossible for them to interfere in the process without the owner's consent. In practice, though, it is not uncommoo. for owners to consent, since the concordata dries up alI sources of credit to the finn (including supplier credit). In the case offinns that crucially depend an supplier credit, such as retailers, creditors often manage the whole reorganizatioo processo

The legal procedures ruling judicial executioo. are perceived to be in general excessively cumbersome and to

alIow

a great number ofways to postpoo.e a decisian. This creates a strang incentive for debtorsto default. A cognizance action lasts, 00. average, five

years.

Once a decisioo. is reach.ed and theexecutioo. actian begins, the debtor has fi.ve days after the penhora to present an embargo. In general, a

lawsuiL Furthcnncre, 1be aeditor does D<lt neat 1.0 prove 1be iIl1'1JlPOSC of1be detltor, onIy thIl thcre are no OIhcr asscts for the penhora (1hat is, that the detJtor is iosoIvcú). lhe MO prooedures are thErefore differaJl. \Vbereas the fraud of aeditmi requires them 1.0 start a new lawsuit (asking the judgel.o caDCd the saJe), in the fraud 1.0 crcc:utim the fad is takcn 1.0 the judge in the excc.utim Iawsuit itsdí

30 UncIer BnziIiIIl baoIauptcy Iaw, debrs arepaid in the following orde.r: (a) flq)loyees' wage cIaims aod indamily; (b) tax cIaims (first federal, then stale aad finaI1y cIaims of DUliàpal tax セI[@ (c) secured aediIs; (4) aediIs \Uh special privileges ovcr a:rtain asscts (commercial

credit cédJUas \Uh penhor are saIÍaI' to penhor, d.c.); (5) aediIs wiIb general priviJeges (e.g., induslrial credit cédJda); anel (6) lIIISeCIII'Cd

aediIs. &nb oftm find tIIanseMs as Iow.gnked c:redilcrs.

31 GcncnI fiscal mmeslies at the municipal, lIlate and fedenlleYels are common in Brazil. In these ÍDlJlances deIltors are abIe 1.0 fmego pEIIalties

for dcfauItin.gtax paymcnt and are givcn favoreci candilims to pay back their debts.

32 A non-liquid but p<úDtially soIwat firm goes into concordam wbcn a judge CXIlcedes an authOl'ÍDticn for it 1.0 resdJedule às debrs, acconIing

to a timctabIe estabIished in the oourt saIlmoe. A concordata may be 'prevaIlive', wbcn às objeâive is 1.0 avoid the ddaioraticn ofthe firm's financiai bealIh, or 'suspcnsive', wbcn during a bmbuptcy the judge cancIudes tbat the firm does D<lt n-' 1.0 be cIosed.