www.jped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Maternal

depression

and

anxiety

and

fetal-neonatal

growth

夽

Tiago

Miguel

Pinto

a,∗,

Filipa

Caldas

b,

Cristina

Nogueira-Silva

c,d,e,

Bárbara

Figueiredo

aaUniversidadedoMinho,EscoladePsicologia,Braga,Portugal

bUniversidadedoMinho,EscoladeCiênciasdaSaúde,Braga,Portugal

cUniversidadedoMinho,EscoladeCiênciasdaSaúde,InstitutodePesquisaemCiênciasdeVidaeSaúde(ICVS),Braga,Portugal

dICVS/3B’s---PTGovernmentAssociateLaboratory,Braga/Guimarães,Portugal eHospitaldeBraga,DepartamentodeObstetríciaeGinecologia,Braga,Portugal

Received21August2016;accepted10November2016 Availableonline20February2017

KEYWORDS Maternaldepression; Maternalanxiety; Fetal-neonatal growthoutcomes; Fetal-neonatal growthtrajectories

Abstract

Objective: Maternaldepressionandanxietyhave beenfound tonegativelyaffect fetaland

neonatalgrowth. However, the independent effectsofmaternal depression andanxietyon fetal-neonatalgrowthoutcomesandtrajectoriesremainunclear.Thisstudyaimedtoanalyze simultaneouslytheeffectsofmaternalprenataldepressionandanxietyon(1)neonatalgrowth outcomes,and(2),onfetal-neonatalgrowthtrajectories,fromthe2ndtrimesterofpregnancy tochildbirth.

Methods: A sample of172 women was recruited andcompleted self-reportedmeasures of

depressionandanxietyduringthe2ndand3rdtrimestersofpregnancy,andatchildbirth.Fetal andneonatalbiometrical datawere collectedfromclinicalreports atthesameassessment moments.

Results: Neonates of prenatally anxious mothers showed lower weight (p=0.006), length

(p=0.025),andponderal index(p=0.049)atbirth thanneonates ofprenatallynon-anxious mothers.Moreover,fetuses-neonatesofhigh-anxietymothersshowedalowerincreaseofweight fromthe2ndtrimesterofpregnancytochildbirththanfetuses-neonatesoflow-anxiety moth-ers(p<0.001).Consideringmaternaldepressionandanxietysimultaneously,onlytheeffectof maternalanxietywasfoundonthesemarkersoffetal-neonatalgrowthoutcomesand trajecto-ries.

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:PintoTM,CaldasF,Nogueira-SilvaC,FigueiredoB.Maternaldepressionandanxietyandfetal-neonatalgrowth. JPediatr(RioJ).2017;93:452---9.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:tmpinto@psi.uminho.pt(T.M.Pinto). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2016.11.005

Conclusion: Thisstudydemonstratestheindependentlongitudinaleffectofmaternalanxietyon majormarkersoffetal-neonatalgrowthoutcomesandtrajectories,simultaneouslyconsidering theeffectofmaternaldepressionandanxiety.

©2017SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/ 4.0/).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Depressãomaternal; Ansiedadematernal; Resultadosde crescimentofetale neonatal;

Trajetóriasde crescimentofetale neonatal

Depressãoeansiedadematernalecrescimentofetal-neonatal

Resumo

Objetivo: Foiconstatadoqueadepressãoeansiedadematernaafetamnegativamenteo

cresci-mento fetaleneonatal.Contudo,oefeitoindependentedadepressãoeansiedadematerna sobreosresultadoseastrajetóriasdecrescimentofetaleneonatalcontinuaincerto.Esteestudo visouanalisarsimultaneamenteoefeitodadepressãoeansiedadematernapré-natal(1)sobre osresultadosdecrescimentoneonatale(2)sobreastrajetóriasdocrescimentofetal-neonatal apartirdo2◦trimestredegravidezatéoparto.

Métodos: Uma amostra de 172 mulheres foi recrutada e as mesmas relataram graus de

depressãoeansiedadeno2◦e3◦trimestredegravidezeparto.Osdadosbiométricosfetaise

neonataisforamcoletadosdosprontuáriosclínicosnasmesmasondasdeavaliac¸ão.

Resultados: Os neonatos de mães ansiosas no período pré-natal mostraram menor peso

(p=0.006),comprimento(p=0.025)eíndiceponderal(p=0.049)nonascimentoqueosneonatos demãesnãoansiosasnoperíodopré-natal.Alémdisso,osneonatosdemãesmuitoansiosas mostraramummenoraumentodepesodo2◦ trimestredegravidezatéopartoqueos

fetos-neonatosdemãespoucoansiosas(p<0.001).Considerandosimultaneamenteadepressãoea ansiedadematernal,apenasoefeitodaansiedadematernafoiconstatadonessesmarcadores deresultadosetrajetóriasdecrescimentofetal-neonatal.

Conclusão: Esteestudodemonstraoefeitolongitudinalindependentedaansiedadematerna

sobreosprincipaismarcadoresderesultadosetrajetóriasdecrescimentofetal-neonatal, con-siderandosimultaneamenteoefeitodadepressãoeansiedadematerna.

©2017SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigo OpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4. 0/).

Introduction

The short-term consequences of prenatal depression and anxietyonpregnantwomen’sphysicalhealthinclude obstet-ric complications and physical symptoms, which areboth associatedwithlowerfetalandneonatalgrowthandlower autonomicnervoussystem (ANS)maturation.1,2 Depression

and anxiety share a common genetic pathway, and often

appear simultaneously, making it difficult to assess their

independenteffects. Thus, when analyzing the effectsof

maternal depression and anxiety, it may be important to

consider both simultaneously, in order to control their

mutualeffectsandtobetteridentifytheindependenteffect

ofeachone.3

Various studies have found similar effects of maternal

prenataldepressionandanxietyonfetalgrowth,behavior,

and ANS maturation. Bothfetuses of depressed and

anx-iousmotherswerefoundtopresentlowerestimatedweight

andhighertotalfetalactivity.4---6 Inaddition,studieshave

found that both fetuses of depressed or anxious mothers

showhigherheartratereactivitycomparedwithfetusesof

non-depressedornon-anxiousmothers.2,7---10

Moreover, studies also have found similar effects of

maternal prenatal depression and anxiety on

neona-tal growth, behavioral, and maturation outcomes. Both

neonatesof prenatally depressedor anxious mothers

pre-sented higher risk of premature birth and low weight,

both major problems of infant health.11---13 Neonates of

depressedor anxious mothers were found topresent

dis-organizedsleeppatternsand frequent changes of mood.2

Lowermaturationwasalsofoundinneonatesofprenatally

depressedor anxious mothers, includingless vagal tonus,

and lower neurobehavioral maturity.2,11,13,14 Furthermore,

both neonates of prenatally depressed or anxious

moth-erswerefoundtoshowhigherlevelsofcortisolandlower

levelsofdopamineandserotoninwhencomparedwith

hor-monal levels of neonates of prenatally non-depressed or

non-anxious mothers.15 Other studies also reported that

both infants of prenatally depressed or anxious mothers

presentincreasedadmissionratestotheneonatalcareunit

andgrowthretardationduringthefirstyearoflife.16,17

Few studies have simultaneously considered

mater-nal depression and anxiety when analyzing the effect

on fetal/neonatal growth and behavior. When

simul-taneously considering maternal depression and anxiety,

studies only found an independent effect of maternal

anxiety on fetal/neonatal growth and behavior.18---20 One

cross-sectional study only found an effect of maternal

anxiety on fetal growth and behavior (fetuses of

activity at mid-pregnancy).18 Additionally, two

longitudi-nal studies only found an effect of maternal anxiety on

fetal-neonatal growth trajectories (higher maternal

anxi-ety during pregnancy was associated with lower increase

offetal-neonatalweight).19,20 However,thesestudiesonly

included one assessment of maternal prenatal depression

andanxiety(duringpregnancy)whenanalyzingtheireffect

onfetal/neonatal growth,not addressing the longitudinal

effectofbothmaternaldepressionandanxiety.

Both maternal depression and anxiety were found to

negativelyaffectfetalandneonatalgrowth.Despitethese

effectshaving been widely documented in literature,the

independent effects of maternal depression and anxiety

onfetal-neonatalgrowthoutcomesandtrajectoriesremain

unclear.Moreover,thereisalackofstudiesthathave

simul-taneouslyaddressedtheindependentlongitudinaleffectof

maternaldepression andanxietyonfetal-neonatalgrowth

trajectories.Thisstudyaimedtosimultaneouslyanalyzethe

effectofmaternal prenataldepression andanxietyon(1)

neonataloutcomes,and(2),onfetal-neonatalgrowth

tra-jectories,fromthe2ndtrimesterofpregnancytochildbirth.

Method

Participants

The sample wascomprised of 172 mothers recruitedat a public health service in Northern Portugal during the 1st trimesterofpregnancy(8---14gestationalweeks).Inclusion criteriawere:abletoreadandwriteinPortuguese;resident inPortugalforatleastoneyear;atmost14weekspregnant; and,singletongestationswithoutmedicaland/orobstetric complications. Fromthe 172 mothers whocompleted the 1stmomentofassessment,88.4%(n=152)completedallthe threemomentsofassessment.

Procedures

Thisstudywasconductedinaccordancewiththe Declara-tionofHelsinkiandwaspreviouslyapprovedbytheethics committeesof all institutions involved. Women willing to participate provided written informed consent, after an explanationof the study aimsandprocedures. This study hadalongitudinaldesignwiththreeassessmentmoments: 2nd trimester of pregnancy (20---24 gestational weeks), 3rd trimester of pregnancy (30---34 gestational weeks), and childbirth (1---3 postnatal days). Mothers repeatedly completed a measure of depression and anxiety. Obstet-ricrecords and fetaland neonatalbiometrical datawere collected from clinical reports during the 2nd and 3rd trimesterof pregnancy,andat childbirth. Toavoid poten-tialerrors associatedwithestimated age, gestationalage wasestimatedbasedonmothers’lastmenstrualperiodand confirmedusingultrasoundmeasurements.

Measures

Socio-demographicandobstetricinformationwasobtained usingasocio-demographicquestionnaire. Toassess mater-nal depression, the Portuguese version of the Edinburgh

PostnatalDepressionScale(EPDS)21,22wasused.TheEPDSis

aself-reportedscalecomposedoftenitemsonafour-point

Likert scale.A cutoffpoint of10wassuggested toscreen

fordepressioninPortuguesewomen.22Severalstudieshave

usedthisscaleinwomenduringpregnancyandthe

postna-talperiod.18---20 ThePortugueseversionoftheEPDSshowed

goodinternal consistency inwomenduring pregnancyand

the postnatal period (˛=0.85).18,22 In the present study,

Cronbach’salphacoefficientsrangedfrom0.84to0.85.

To assess maternal anxiety, the Portuguese version of

the State-TraitAnxiety Inventory(STAI)23,24 wasused.The

STAIiscomposedoftwosubscales:onetoassessanxietyas

anemotional state(STAI-S)andanothertoassessthetrait

of anxiety (STAI-T), each containing20 items scored ona

four-pointLikertscale.Acutoffpointof45wassuggested

toscreenfor highanxietyinPortuguese women.24 Several

studieshaveusedthismeasureinwomenduringpregnancy

andthepostnatalperiod.18,19ThePortugueseversionofthe

STAI-S showed goodinternal consistency in women during

pregnancyandthepostnatalperiod(˛rangedfrom0.87to

0.93).24Inthepresentsample,Cronbach’salphacoefficients

ofSTAI-Srangedfrom0.89to0.93.

Toassessfetalgrowth,estimatedfetalweight(measured

ingrams)wasobtainedfromtheobstetricultrasoundsatthe

2ndand3rdtrimestersofpregnancy.Thesemeasureswere

obtainedfollowingastandardclinicalmeasurement

proto-colby an obstetrician fromtheresearchteam. Estimated

fetalweightwascalculatedusingtheHadlockformula.25

To assess neonatalgrowth outcomes, neonatalweight,

length (measured in centimeters), ponderal index

(100× [weight/length3]), and gestational age at birth

(measuredinweeks)werecollectedfrommedicalreports.

These measures were suggested by previous research as

majormarkersoffetal-neonatalgrowthandoutcomes.18---20

Dataanalysisstrategy

To simultaneouslyanalyzetheeffectofmaternal prenatal depression and anxiety onneonataloutcomes, a two-way multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was per-formed. In the model, maternal prenatal depression and anxiety (meanof thescores at the 2ndand3rd trimester of pregnancy; coded as0=EPDS<10 and 1=EPDS≥10 for

depression; 0=STAI-S<45 and 1=STAI-S≥45 for anxiety)

wereincludedasindependentvariablesandneonatalgrowth outcomes(weight,length,ponderalindex,andgestational ageatbirth)asdependentvariables.Themother’sweight before pregnancy and tobacco and coffee consumption during pregnancy were included as covariates. The two-way MANCOVAwas performed using SPSS (IBM Corp; SPSS StatisticsforWindows,version23.0.USA).Theeffectsize, measured aspartial eta squared (p2),waspresented for

thetwo-wayMANCOVAresults.

anxiety symptoms (STAI-S scores) wereexamined at each assessmentmoment.Fixedeffectsformaternaldepressive and anxiety symptoms (time-varying effects centered on their grand means) were included in the model. Two dif-ferent models were performed (the unconditional model andthemodelwithpredictors).Themother’sweightbefore pregnancyandtobaccoandcoffeeconsumptionduring preg-nancywereincluded ascovariates.Significant interactions wereinterpretedandgraphedusingonestandarddeviation above and below the grand mean of the predictor varia-blesashighandlowvalues.Adeviancedifferencetestwas performedbetweentheunconditionalmodelandthemodel withpredictors toexaminemodelfitimprovements.GCMs wereperformed in apairwise person-perioddatasetusing SPSSversion23.0(SPSSInc.,UnitedStates).The resulting data consisted of 516 potential observations(172 partici-pantsbythreetimepoints).Theeffectsizerwasestimated forallsignificanteffects.

Results

Nearly all the mothers were Portuguese (92.1%), white (94.8%), married or cohabiting (86.8%), and living with a partner (86.2%). More than half were aged between 18 and 29 years old (M=27.69, SD=5.82), were of medium-low or low socio-economic level (62.0%), were employed (67.1%),and hadbetweennine and12yearsof education (54.5%).Additionally,morethanahalfofthemotherswere primiparous (52.1%) and had an eutocic delivery (with or withoutepidural;56.3%).Themajorityreportednotobacco consumption during pregnancy (83.8%), more than a half reportednocoffee consumption (70.7%),and allreported noalcoholanddrugconsumptionduringpregnancy.

Morethanahalfoftheneonatesweremales(56.3%)and bornwithalength≥50cm(63.5%).Themajoritywerenot

reanimated at birth (94.0%),born witha weightbetween 2500and4199g(91.0%),aponderalindex≥2.50(81.2%),a

gestationalage atbirthof≥37weeks(95.8%),andhadan

Apgar scorebetween 7 and10 at the1st (92.6%)and 5th minute(98.8%),respectively(Table1).

Noassociationsanddifferenceswerefoundbetweenthe

mothers that completed and did not complete the three

assessment moments, regarding mothers’ and neonates’

variables.

Additionally,noassociationsanddifferenceswerefound

betweenthemothersthatcompletedanddidnotcomplete

thethreeassessmentmomentsinallthestudyvariablesat

eachmomentofassessment.

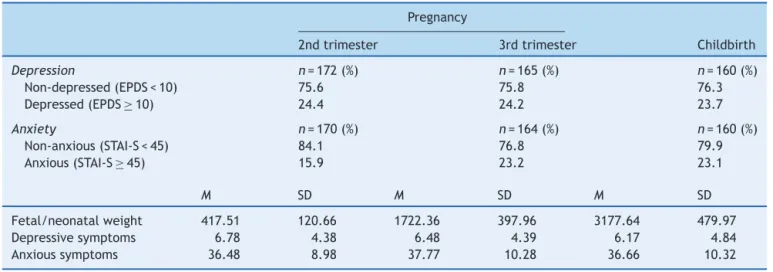

Descriptive statistics for all study variables at each

assessment were performed (Table2). Significant

associa-tionswerefoundamongthestudyvariablesatthebaseline

(r ranging from−0.289, p<0.05, to 0.652, p<0.001). No

association wasfoundbetween fetalweightandmaternal

depressivesymptomsatthebaseline.

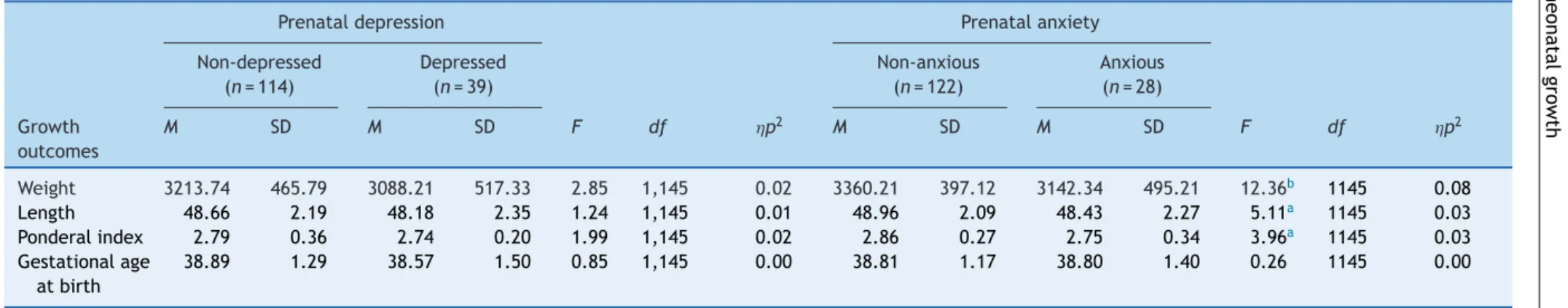

Theeffectsofmaternalprenataldepressionand

anxietyonneonatalgrowthoutcomes

The two-way MANCOVA revealed significant multivariate effects of maternal prenatal anxiety on neonatal growth outcomes,Wilk’s Lambda=0.91, F(4,142)=3.29, p=0.013,

Table1 Mothers’obstetricandsocio-demographic charac-teristicsandneonates’biometricdata.

Mothers

n=172(%)

Age(years) 15---17 4.8 18---29 51.5 30---41 43.7 Socio-economic

level

High 15.7

Medium-high 4.7 Medium 17.6 Medium-low 22.2

Low 39.8

Professional status

Employed 67.1 Unemployed 25.7 Household/student 7.2 Education(in

years)

<9 27.5 9---12 54.5 >12 18.0 Parity Primiparous 52.1 Multiparous 47.9 Deliverytype Eutocic 56.3 Dystocic 43.7 Tobacco

consumption

Yes 16.2

No 83.8

Coffee consumption

Yes 29.3

No 70.7

Neonates

n=168(%)

Sex Male 56.3

Female 43.7 Reanimation Yes 6.0

No 94.0

Weight(g) <2500 6.6 2500---4199 91.0

≥4200 2.4

Length(cm) <50 63.5

≥50 36.5

PonderalIndex <2.50 18.8

≥2.50 81.2

Gestationalage atbirth (weeks)

<37 4.2

≥37 95.8

p2=0.09. Results revealed significant univariate effects

Table2 Descriptivestatisticsofstudyvariablesacrosstime.

Pregnancy

2ndtrimester 3rdtrimester Childbirth

Depression n=172(%) n=165(%) n=160(%)

Non-depressed(EPDS<10) 75.6 75.8 76.3 Depressed(EPDS≥10) 24.4 24.2 23.7

Anxiety n=170(%) n=164(%) n=160(%)

Non-anxious(STAI-S<45) 84.1 76.8 79.9 Anxious(STAI-S≥45) 15.9 23.2 23.1

M SD M SD M SD

Fetal/neonatalweight 417.51 120.66 1722.36 397.96 3177.64 479.97 Depressivesymptoms 6.78 4.38 6.48 4.39 6.17 4.84 Anxioussymptoms 36.48 8.98 37.77 10.28 36.66 10.32

M,mean;SD,standarddeviation;EPDS,EdinburghPostnatalDepressionScale;STAI-S,stateanxietyinventory.

Nosignificantmultivariateeffectsofprenatalmaternal depressionwerefoundonneonatalgrowthoutcomes,Wilk’s Lambda=0.95,F(4,142)=1.92,p=0.110,p2=0.05.

Theeffectsofmaternaldepressionandanxietyon

fetal-neonatalgrowthtrajectories,fromthe2nd

trimesterofpregnancytochildbirth

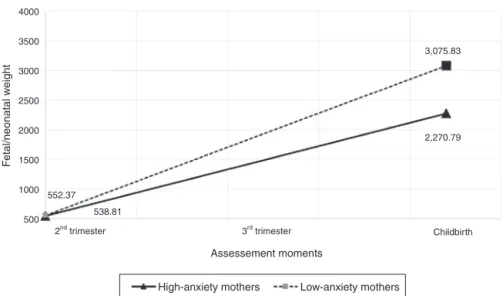

The main effects over timewere found onfetal-neonatal weight, b=96.71, SE=1.71, 95% CI=[93.33, 100.08],

p<0.001, effect size r=0.95. From the 2nd trimester of pregnancytochildbirth,fetal-neonatalweightincreased,on average,97gperweek.Additionally,interactioneffectsof anxietysymptomsandtimewerefound,b=2.65,SE=0.10, 95%CI=[2.45,2.86],p<0.001,effectsizer=0.86. Fetuses-neonatesofhigh-anxietymothersshowedalowerincrease ofweightfromthe2ndtrimesterofpregnancytochildbirth thanfetuses-neonatesoflow-anxiety mothers(Fig.1).No

maineffectsofmaternalanxietysymptomswerefoundon

fetalweight.

No main effects of maternal depressive symptoms

were found on fetal weight. Likewise, no effects of

the interaction between maternal depressive symptoms

and time, and no effects of the interaction between

maternal depressive symptoms, maternal anxiety

symp-toms,andtimewerefound. Interceptandrandomeffects

(intercept+time; residuals) were statistically significant

(all values of p<0.001). The deviance difference test

showedthat themodel withpredictors (maternal

depres-siveandanxietysymptoms)providedagoodfittothedata,

2(5)=138.87,p<0.001.

Discussion

Simultaneously considering the effect of maternal prena-taldepressionandanxiety,asignificantindependenteffect ofprenatalmaternal anxietywasfoundonmajormarkers ofneonatalgrowthoutcomes.Neonatesofprenatally anx-ious mothers showed lower weight, length, and ponderal

indexatbirththanneonatesofprenatallynon-anxious moth-ers. These results are consistent withprior research that found that neonates of anxious mothers were born with lowerweight,length,andponderalindex.2Moreover,

simul-taneously considering maternal depression and anxiety, a

significantinteractioneffectofmaternalanxietysymptoms

and time wasfound on a major markerof fetal-neonatal

growth.Thisresultsuggestedaneffectofmaternalanxiety

symptoms onfetal-neonatalweighttrajectories, fromthe

2ndtrimesterofpregnancytochildbirth.Fetuses-neonates

ofanxiousmothersshowedalowerincreaseofweight,from

the2ndtrimesterofpregnancytochildbirth,than

fetuses-neonates of non-anxious mothers. These findings suggest

thatmaternal anxietynegatively affectthismajormarker

of normativefetal-neonatal growthtrajectories, fromthe

prenatal period to childbirth, even when simultaneously

considering the effectof maternal depression.This result

is consistent with previous research that found a lower

increaseof weightin fetuses-neonatesof anxiousmothers

thaninfetuses-neonatesofnon-anxiousmothersfrom

preg-nancytochildbirth.18,19

Severalunderlyingmechanismshavebeen suggestedto

explain the effect of maternal anxiety on fetal-neonatal

growth. Epigenetic mechanisms have been proposed as

possiblemediatorsoftheprenatalanxietyeffecton

fetal-neonatal growth. Studies have suggested that prenatal

anxiety can permanently alter fetal physiology, namely

hyperactivationofthefetalhypothalamicpituitaryadrenal

(HPA)axis.26,27 Literaturehasalso suggestedthe mother’s

HPAhyperactivationasamediatorofthematernalprenatal

anxiety effect on fetal-neonatal growth.28 Prenatal

anxi-ety could be a stressor for pregnant women, stimulating

the HPA-axis to produce higher levels of glucocorticoids.

Maternal glucocorticoids can be transduced to the fetus

by transplacental transport andby stress-induced release

of placental hormones into fetal circulation. Increased

fetal cortisol contributes to the maturation of organ

systemsrequiredforextra-uterinesurvival.However,

exces-sive levels of feto-placental glucocorticoid may result in

intrauterinegrowthrestriction.28 Further,maternal

depression

and

anxiety

,

fetal-neonatal

growth

457

Table3 Theeffectofmaternalprenataldepressionandanxietyonneonatalgrowthoutcomes.

Prenataldepression Prenatalanxiety Non-depressed Depressed Non-anxious Anxious

(n=114) (n=39) (n=122) (n=28) Growth

outcomes

M SD M SD F df p2 M SD M SD F df p2

Weight 3213.74 465.79 3088.21 517.33 2.85 1,145 0.02 3360.21 397.12 3142.34 495.21 12.36b 1145 0.08

Length 48.66 2.19 48.18 2.35 1.24 1,145 0.01 48.96 2.09 48.43 2.27 5.11a 1145 0.03

Ponderalindex 2.79 0.36 2.74 0.20 1.99 1,145 0.02 2.86 0.27 2.75 0.34 3.96a 1145 0.03

Gestationalage atbirth

38.89 1.29 38.57 1.50 0.85 1,145 0.00 38.81 1.17 38.80 1.40 0.26 1145 0.00

M,mean;SD,standarddeviation.

Note:Mother’sweightbeforepregnancyandtobaccoandcoffeeconsumptionduringpregnancywereincludedascovariates. a p<0.05.

4000

3500

3000

2500

2000

1500

1000

500

2nd trimester 3rd trimester

Assessement moments

F

etal/neonatal w

eight

Childbirth

High-anxiety mothers Low-anxiety mothers

552.37 538.81

3,075.83

2,270.79

Figure1 Estimatedweighttrajectoriesforfetuses-neonatesofhigh-anxietyandlow-anxietymothers.

intakeandlowintakeofessentialvitaminsandfattyacids (e.g.,folicacid,vitaminB12).29

Majorconcernsaboutlowbirthweight,length,and

pon-deralindexemergedduetotheirnegativeeffectoninfant

health,associatedwithhigherperinatalmortality:

mechan-ical ventilation, supplemental oxygen support, later oral

feeding, retinopathy, bronchopulmonary dysplasia,

pneu-mothorax,intraventricularhemorrhage,andotherpediatric

complications.30 Moreover, more developmental problems

wereidentifiedinlowbirthweightneonates,including

prob-lemsofattention, cognition,andneuromotorfunctioning,

andincreasingtheriskofearlychildhoodmorbidity.30

Some limitations shouldbe pointed out.The voluntary

natureofthe participationinthe studymay havelead to

a selection bias. Mothers who agreed to participate and

completed all moments of assessment may be those who

feelmoresatisfiedandinvolvedwiththepregnancy

expe-rience.However, nodifferences were found between the

participantswho completedand did notcomplete allthe

momentsofassessment.Ahighersamplesizemightincrease

thestatisticalpoweroftheanalysis.Astandardizedclinical

interviewtoassess depression and anxiety couldincrease

thevalidityoftheresults.However,bothmeasuresshowed

goodinternalconsistency.Unmeasuredconfoundingfactors

mayhaveinfluencedtheeffectsdescribed.However,some

ofthesefactors(mother’sweightbeforepregnancy,tobacco

andcoffeeconsumptionduringpregnancy)werecontrolled

intheanalysis.

This study demonstrates the independent longitudinal

effect of maternal anxiety on major markers of

fetal-neonatalgrowthoutcomesandtrajectories,simultaneously

considering the effect of maternal depression and

anxi-ety. This highlights an increased necessity of systematic

screeningforanxietyduringpregnancy.Thesefindingsalso

suggested that fetuses of anxious mothers are those who

might benefit from individualized care in neonatal care

units.

Suggestionstofutureresearchcanbeindicated.Future

studies could simultaneously explore the independent

effects of both maternal depression and anxiety on

other markers of fetal-neonatal growth, behavior, and

maturation. Futureresearchcouldalso explorethe

medi-atorroleofepigeneticandendophenotypicmechanismson

the effectof maternal prenatalanxiety on fetal-neonatal

growthoutcomesandtrajectories.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgments

ThisstudywasconductedatthePsychologyResearchCenter (UID/PSI/01662/2013),University ofMinho,andsupported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technol-ogyand thePortuguese Ministryof Education andScience throughnational funds andco-financed by FEDERthrough COMPETE2020 under the PT2020 Partnership Agreement (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007653). This study was also sup-portedby FEDERFundsthroughthe ProgramaOperacional Factores deCompetitividade --- COMPETE and by National FundsthroughFCT---Fundac¸ãoparaaCiênciaeaTecnologia undertheprojectPTDC/SAU/SAP/116738/2010.

References

1.AnderssonL,Sundström-PoromaaI,WulffM,AströmM,BixoM. Implicationsofantenataldepressionandanxietyforobstetric outcome.ObstetGynecol.2004;104:467---76.

2.Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C, YandoR, et al. Pregnancy anxiety and comorbid depression andanger:effectsonthefetusandneonate.DepressAnxiety. 2003;17:140---51.

3.BeukeCJ,FischerR,McDowallJ.Anxietyanddepression:why andhowtomeasuretheirseparate effects.ClinPsycholRev. 2003;23:831---48.

5.Diego MA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C,Gonzalez-Quintero VH. Prenataldepression restricts fetal growth.EarlyHumDev.2009;85:65---70.

6.DieterJN,FieldT,Hernandez-ReifM,JonesNA,LecanuetJP, SalmanFA,etal.Maternaldepressionandincreasedfetal activ-ity.JObstetGynaecol.2001;21:468---73.

7.AllisterL, Lester BM,CarrS, LiuJ. Theeffects ofmaternal depressiononfetalheartrateresponsetovibroacoustic stimu-lation.DevNeuropsychol.2001;20:639---51.

8.FuJ,YangR,MaX,XiaH.Associationbetweenmaternal psy-chological status and fetal hemodynamic circulation in late pregnancy.ChinMedJ(Engl).2014;127:2475---8.

9.MonkC,Myers MM,SloanRP,EllmanLM,Fifer WP.Effectsof women’sstress-elicitedphysiologicalactivityandchronic anxi-etyonfetalheartrate.JDevBehavPediatr.2003;24:32---8. 10.DiPietroJA, Costigan KA, Gurewitsch ED. Fetal response to

inducedmaternalstress.EarlyHumDev.2003;74:125---38. 11.FieldT,DiegoM,DieterJ,Hernandez-ReifM,SchanbergS,Kuhn

C,etal.Prenataldepressioneffectsonthefetusandthe new-born.InfBehavDev.2004;27:216---29.

12.HoffmanMC,MazzoniSE,WagnerBD,LaudenslagerML,RossRG. Measuresofmaternalstressandmoodinrelationtopreterm birth.ObstetGynecol.2016;127:545---52.

13.MartiniJ,KnappeS,Beesdo-BaumK,LiebR,WittchenHU. Anx-ietydisordersbefore birthandself-perceived distress during pregnancy:associationswithmaternaldepressionand obstet-ric,neonatal and earlychildhood outcomes.EarlyHum Dev. 2010;86:305---10.

14.FieldT,DiegoM,DieterJ,Hernandez-ReifM,SchanbergS,Kuhn C,etal.Depressedwithdrawnandintrusivemothers’effectson theirfetusesandneonates.InfantBehavDev.2001;24:27---39. 15.AshmanSB,DawsonG,PanagiotidesH,YamadaE,WilkinsonCW.

Stresshormonelevelsofchildrenofdepressedmothers.Dev Psychopathol.2002;14:333---49.

16.CarterJD,MulderRT,BartramAF,DarlowBA.Infantsina neona-talintensivecareunit:parentalresponse.ArchDisChildFetal NeonatalEd.2005;90:F109---13.

17.Davis EP, Sandman CA. The timing of prenatal exposure to maternal cortisol and psychosocial stress is associ-ated with human infant cognitive development. Child Dev. 2010;81:131---48.

18.CondeA,FigueiredoB,TendaisI,TeixeiraC,CostaR,PachecoA, etal.Mother’sanxietyanddepressionandassociatedrisk fac-torsduringearlypregnancy:effectsonfetalgrowthandactivity at20---22 weeksofgestation. JPsychosom ObstetGynaecol. 2010;31:70---82.

19.Henrichs J, Schenk JJ, Roza SJ, van den Berg MP, Schmidt HG, Steegers EA, et al. Maternal psychological distress and

fetalgrowthtrajectories:theGenerationRStudy.PsycholMed. 2010;40:633---43.

20.HompesT, VriezeE,FieuwsS,SimonsA, JaspersL, Van Bus-selJ,etal.Theinfluenceofmaternalcortisolandemotional state duringpregnancyon fetal intrauterine growth.Pediatr Res.2012;72:305---15.

21.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Developmentofthe10-item Edinburgh Postnatal DepressionScale.BrJPsychiatry.1987;150:782---6.

22.AreiasME,KumarR,BarrosH,FigueiredoE.Comparative inci-dence of depression in women and men, during pregnancy and after childbirth. Validation of the Edinburgh Postna-talDepression Scalein Portuguesemothers. Br JPsychiatry. 1996;169:30---5.

23.BiaggioAM,NatalicioL,SpielbergerCD.Thedevelopmentand validation ofanexperimental Portugueseform ofthe State-TraitAnxiety Inventory. In: SpielbergerCD, Dias-Guerrero R, editors.Cross-culturalresearchonanxiety.Washington,D.C.: Hemisphere/Wiley;1976.p.29---40.

24.SpielbergerCD,GorsuchRL,LusheneR, VaggPR,JacobsGA. Manualforthestate-traitanxietyinventory.PaloAlto: Consul-tingPsychologistsPressInc.;1983.

25.HadlockFP,HarristRB,CarpenterRJ,DeterRL,ParkSK. Sono-graphicestimationoffetalweight.Thevalueoffemurlength in addition to head and abdomen measurements. Radiology. 1984;150:535---40.

26.Palma-Gudiel H, Córdova-Palomera A, Eixarch E, Deuschle M,Fa˜nanás L. Maternalpsychosocialstress duringpregnancy alterstheepigeneticsignatureoftheglucocorticoidreceptor genepromoterintheiroffspring:ameta-analysis.Epigenetics. 2015;10:893---902.

27.HompesT,IzziB,GellensE,MorreelsM,FieuwsS,PexstersA, etal.Investigatingtheinfluenceofmaternalcortisoland emo-tionalstateduringpregnancyontheDNAmethylationstatusof theglucocorticoidreceptorgene(NR3C1)promoterregionin cordblood.JPsychiatrRes.2013;47:880---91.

28.Wadhwa PD, Garite TJ, Porto M, Glynn L, Chicz-DeMet A, Dunkel-SchetterC,etal.Placentalcorticotropin-releasing hor-mone (CRH), spontaneous preterm birth, and fetal growth restriction:aprospectiveinvestigation.AmJObstetGynecol. 2004;191:1063---9.

29.EmmettPM,JonesLR, GoldingJ. Pregnancydietand associ-atedoutcomesintheAvonLongitudinalStudyofParentsand Children.NutrRev.2015;73:154---74.