•

Fundação Getulio Vargas

E

p

G

E

Escola de P6s-Graduação em Economia

Seminários de Pesquisa Econômiç,a 11

(2ª parte)

Mareio Gare-ia

(PUCIRJ)

'~AVOmIRG

COST8

O~

IRFLATION ARI) C_A WLIRG

TOWABJ) IIYPEBmTLATIORI

TRE

OAB

OI'

T-I!

eVa __

RCY

8VB8TITVI'B"

'LOCAL:

Fundação Getulio Vargas

DATA:

HORÁRIO:

\marf < IPraia de Botafogo, 190 - 10

0andar

Sala 1021

03111194 (quinta-feira)

15:30h

Coordenação: Prof. Pedro Ca\alcanti FerreIra Tel 536-1)~5~

'"

'1•

•

•

Avoiding some costs of intlation and crawling toward hyperintlation:

The case of the Brazilian domestic currency substitute

Márcio G. P. Garcia

PUC-Rio (Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Ianeiro)

Dept. of Economics - PUC-Rio

Rua Marquês

deSão Vicente, 225

Rio

deIaneiro - RJ - 22453-040 - Brazil

ph. (5521) 274-2797 Fax (5521) 294-2095

e-mail: mgarcia@brlncc.bitnet

Abstract

..

The pattem of a classical hyperinflation is an acute acceleration of the inflation levei

accompanied by rapid substitution away from domestic currency. Brazil, however,

hasbecn experiencing inflation leveis well above 1,000% a year since 1988 without

entering the classical hyperinflation path. Two elements play key roles

indiffercntiating the Brazilian case from other hyperinflationary experiences: indexation

and

the provision of a reliable domestic currency substitute, Le., the provision of

liquidity to interest-bearing assets. This paper claims that the existence of this domestic

currency substitute is

lhe mainsource of both

lhe inabilityof the Brazilian central bank

to fight inflation and of the unwillingness of Brazilians to face the costs of such a fight.

The provision of the domestic currency substitute through the banking sector

ismodeled,

andthe

mainmacroeconomic consequences of

thismonetary regime are

derived. Those are: the lack of a nominal anchor for the price system due to the

passive monetary policy; the endogeneity of seignorage

unlikctraditional

modelsof

hyperinflation; and

lheineffectiveness of very

highreal interest rates.

Latest update on April26, 1994

This

paper was partially wriucn while

Iwas visiting

lheEconomics Department at

MIT, sponsored by The World Economy Laboratory.

Iwould

likcto

thankCNPq for

a research

gran~ andAndrew

Bem~Dionísio Carneiro, Eduardo Fernandes,

Edward

Arnadeo,Luiz Orenstein, Marco Bonomo, Marina Mello, René Garcia,

Rubens Cysne, Sc!rgio WC2"lang, Stanlcy Fischer, Thadcu

Kclletand Walter Ness for

very helpfu1 comments. Hamilton

Kai,Eugênia Oliveira

andPatrícia Aquino provided

•

•

21. Introduction

The pattem of a classical hyperinflation is an aeute aeceleration of the intlation rate until it reaches extremely high leveIs. For example, the maximwn monthly intlation , rate was 41. 9 . 101.5% on the second Hungarian hyperinflation (August 1945 to July

1946); 85.5 ·10'% on the Greek hyperinflation (November 1943 to November 1944);

and 32,400% on the Gennan hyperinflation (August 1922 to November 1923) (Saehs and Larrain [1993)}. Such aeceleration of the intlation rate is typically accompanied by

rapid substitution away from domestic currency.

10

Brazil, however, has been experiencing intlation leveIs well above 1,000% a year

since

1988 (except in 1990) without entering the classical hyperinflation path. Following

Cagan's definition of hyperinflation (it begins in the month the intlation rate exceeds

50%, and it ends in the month before the monthly rise in prices drops below 50% and stays below for at least a year), Brazil experienced a hyperinflation between December

1989 and March 1990 (Saehs and Lamin [1993]). This was a very special peri~ just

before lhe inauguration of lhe Collor administration (3/15/1990), when such high rates

of intlation were caused by a

general

fear of a dcfault of the internal govemment debt (the debt denominated in NCz$). Figure 1 shows that after this unusual episodeinflanon fell for a whi1e doe to the freezing of financial assets, resumed again, fell once more doe to an eventually unsuccessful price freezing on February 1991 (Collor II

plan) and has been rising ever since, having surpassed lhe 40% monthly leveI in lhe

first quarter of 1994. The stylizcd fact shown in Figure 1 is that B~an intlation has

not been kill~ nor

bas

it displayed lhe explosive pattem of the classical hyperint1anons. This inflation pattem will be refened to as megainftatiOll.1 Table 1Carneiro and Garcia [1993] sunest this tam for lhe Brazilian infIation since it reached lhe

~ per month Ievd. Dornbusch. Sturzenener and WoIf sunest lhe name extreme inflation to

charactaize inftationary procesaea with raieI ;n excell of 15 to 20 JHrCelll per month. slUtailled for

more tNua afow molllM (Sturzenener [1991]). This conespollds to a threshold oil.()()()% per yeBI.

By this criterion lhe Brazilian case fits in lhe extreme inflation calegory. However. there are substantial differences between lhe Brazilian case anel lhe characterizaâon oi extreme infIation Iaid

•

3

displays the GDP growth and inflation rates for Brazil. Despite its declde-long crisis,

the Brazilian economy has exhibitcd a surprising resilience to extremely high and persistent inflation rates.

, Two elements play kcy roles in differentiating the Brazilian case from other

hyperinflationary experiences: indexation· and lhe provision of a rcliable domestic

currency substitute, Le., an interest-bearing asset with near money liquidity. This paper claims that the existence of this domestic currency substitute is the main source of both

the inability of the Brazilian Central Bank to fight inflation and of the

unwillingncss

of Brazilians to face the costs of such a fight•

Since the mid-sixties Brazil has followed economic policies

aimed

at coping withinflation. Widespread indexation gave Brazilians the idea that it would be possible to cope with inflation by avoiding

some

of its costs. Besides indexation, the otherfundamental mechanisrn used to cope with inflation is lhe domestic currency substitute. Brazilians that have access to 'such assets can be protectcd from lhe

inflation tax without giving up lhe liquidity. Since the rich are the most influential in

the political arena, the fact that lhe existence of this domestic currency substitute allowed them to evade a substantial part of the inflation tax plays a decisive role in

explaining why Brazil

has

not undergone a serious anti-inflationary program for solongo

In order to sustain this provision of the domestic currency substitute, lhe Central Bank

has no other option but to follow a highly accommodative monetary policy. Given a very high inflation rate (currendy at an annualimi rate of more than 5,500%), agents

economize on their real balances as much as possible (Ml is currendy less than 1.5%

of.GDP). They do so by holding moncy market accounts-which are believed to be protectcd from the inflation tax-and transferring funds from those accounts to

regular demand deposit accounts whenever needcd (this traDsfer is now done automatically by most large banks). Whenever a check is drawn on bank A, the money

•

4

market fund managed by bank A has to sell securities to get the reserves needed.

These securities are mainly govemment bills, traded in the open martet (this is the

actual narnc in Brazil for the market where banks and the Central Bank trade bank reserves for govemment securities). To be able to provide inflation-protected money substitutes with overnight liquidity, banks have to be able to trade huge amounts of securities (vis-à-vis the small amount of bank reserves they hold) in lhe open market .

without ineurring lhe risk

oI

Iarge capitallosses. That means that lhe Central Bank .has to target the interest rale at a leveI compatible with that goal, and that is indeed the

monetary policy regime that has becn followed in Brazil for the last 2S years with very

few short exceptions.

By targeting the interest rate in lhe open

martet,

the Central Bank completely loses lhe control of the monetary base, and consequendy, of M1.2 The interest rate targeting rcquires the Central Bank to intervene continuously and massively in the open market.This is because the volumes traded are huge in comparison to the small bank reserves. It is not unusual for the Brazilian Central Bank to inject a whole monetary base (300%

of bank reserves) in one single day! In face of such relatively large reserve needs from

the financiaI sector, lhe Central Bank canoot hope to control money if it aims to

sustain the banks' provision of lhe domestic currency substitute.

Section 2 contains a three-period modcl that represents the banks' problem of providing liquidity to interest-bearing assets. This modcl is used to show the limi1S

imposed on mooetary policy in a context of rnegainflation. In Section 3, a few

macroeconomic consequences of lhe provision of lhe dorncstic currency substitute are derived and the maio peculiar characteristics of rnegainflation are presented. Among

the later, ooe importaot feature is that lhe dynamics of rnegainflation are not driven by

2 The Central Bank has no control on lhe other monetmy aggregatel either. because there are no reserve requiremenlS on other componenlS eX M2. M3 OI' M4. Those aggregatel are compoeed eX securities thal are either indexed 10 inflation OI' already incorporalie inflation expectations in lhe

nominal late. 1berefore. lhe non-Ml part eX dIOIe aggregatel PU"" with infIation irrespective eX lhe

"

,

5

a need of financing a given budget deticit through seignorage as it is

usually

assumedin

modcls

of hyperinflation (Bruno and Fischer [1990)). Section 4 concludcs andIays

out topics for future research.

TABLEl.

REAL GDP GROWfH AND INFLATION

REAL GDP GROwm % INFLA TION % per year

1981 -4.40 95.20 1982 0.60 99.70 1983 -3.50 211.00 1984 5.30 223.80 1985 7.90 235.10 1986 7.60 65.00 1987 3.60 415.80 1988 -0.10 1037.60 1989 3.30 1782.90 1990 -4.40 1476.60 1991 0.90 380.30 1992 -1.00 1157.80 1993 4.96 2708.60

•

,

•

6

2. The eonstraints to monetary polley imposed by liquid

interest-bearing asset.j

The model has three periods-l;l. and 3-and 3 agents: a single bank (representing

the whole financiai system), the Central Bank and the households. The households'

aggregate financiai wealth in period I,

W.,

is entirely deposited at the bank in the fonn. . .

.of demand deposits, M .. 3 and money market deposits, MM •. The demand deposits do.

not pay any interest and are subject to reserve requirements of

a

·100%. There is nocurrency. The money market deposits pay a real rate of interest

T.,

between period 1and period 2. The money market nominal continuous rate (7t

+

ri) is contractedbetween the bank and the households in period 1. The inflation rale 1t is assumed

known and constant for alI the periods.

The liability side of the bank's balance sheet in lhe first period is lherefore composed of M. and MM. (a total of W.). The asset side is composed of bank reserves (a

núnimum of

a·

MI) and two-period govemment securities (call them T-bills). TheseT-bills pay one nominal monetary unit in period 3, and are sold in period one at the

unitary price of U1,2 =exp(-27t -ru )' where rl.l is the "long" real rate between

period 1 and period 3.4 The bank buys

B.

of those T-bills (a maximum of~WI

-a·

~)·U1,2}).

For simplicity it is asswncd that: a) lhe bank pays a rate of interest on its money

market liabilities equaI to the rate paid OR govemment bonds; b) lhe expectations

hypothesis of the tenn sttucture of interest rates holds, i.e.,

r

1.l=

ri

+

Et(r

2 ); and c)3 Since lhe foeus oi this model is on lhe banb' probIem. no explicit miaofoundation is offered

f« why lhe housdIolds demand money. A sequei 10 this papel' wiII attempt 10 complete lhe model,

incorporating ao explicit cash-in-advance rationale f« money demand.

4 Thc first subscript relera 10 lhe pc:riod in which lhe variable enters f« lhe first lime in lhe

bank's information set, aod lhe second subscrlpt refera 10 lhe number ( Í pc:riods involved in lhe

variabIe's definition. The second sublcript iI omitted when lhe v.-iabIe refera 110 one pc:riod onIy; for

7

the yieJd curve is flat, Le., r l,l

=

2 . ri' These asswnptions imply that E 1 (r 2)=

ri' ByIensen's inequality, this implies that E1[U1.l/(U1 U2)]~1, where UI =exp(-7t-rl ),

i=I,2. In words, under the above three assumptions, because of negative convexity

(Le., concavity), a strategy of buying two-period bOnds and selling the same nominal

amount of one-period deposits to ~ automatically renewed from periQd 2 to period 3

should yield a negative expectcd profit in period 3. The results, however, will not

crucially depend on lhe three above hypotheses.

The interest rate in period 2, r 2' is set by lhe Central Bank through open market

interventions, and is not known as of period 1. In period 2 there is a shock to money dcmand, ~. In expectcd value tenns, money dcmand grows at rate 7t, i.e., E 1 [~] = exp (X) . ~. This assumption about money dcmand is adcquate for short

periods undcr high inflation. Given lhe new money deman~ lhe households deposit lhe remaining assets in the money market, Le., ~

=

(~+

MM.lU1 - ~).The bank's problem is, therefore, one of transfonning maturities. The bank's deposits

may be withdrawn in period 2, but its assets are redeemable at face value only in

period 3. Since the open market operates in all periods, lhe bank can always seU in

period 2 its "long" securities for its maJket price, U2, which is dctennined by the

Central Bank. After trading in the open market, lhe bank holds B2 in T-bills that matures in period 3. The reserve requirements in period 2 are ~

=

(~.

~).In lhe last period, period 3, lhe bank pays lhe families (~+ MMz./U 2) and receives from lhe Central Bank lhe reserve requirements R2 and lhe bonds B2. The focus of this

analysis is lhe expectcd discountcd value of lhe bank's profits in period 3. Figure 2

displays lhe bank's cash flow.

•

..

8

I

UI.2.[~ +~

-(Mz +MMz/UI )]+1

MAX EI

UI'[(~ -~)+(I\ -~)·UI +(~

-M1)+(MM"-~/UI)]+

(1)a.B2.IIl.R2

l[~ +~

-Bt

'U1,l-~]

J

subject to:

Balance sheet identities

~ +

B.z

= Mz +MMz/U

I + ProfitBt

'UI +~+Mz+MMz= ~ +MMdUI+~+~ 'UI~ +~ =~

+Bt

·U1.2

Reserve requirements

i=I,2

Household' s budget constraints

~+~=w.

Mz +

MMz

= ~ + MM.lU1Demand for money (dcmand deposits)

~

= P I .f:y

'exp(-a .1t) +e,J

~ = P1 ·cxp(1t)·[y ·exp(-a·1t)+~]

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

The balance sheet idcntities say that for each of lhe three periods, all entries add up to zero. Therefore, lhe expected discounted value of lhe bank' s profits in period

3

maybe written simplyas EI

trl.1 .

[~

+B.z

-(~

+ MM"/UI )D·

To obtain funher insight about this problem, we first solve its dcterministic version. Since lhe stochastic variables not known in period 1 are r2 and E2, we set both to their

,

•

9 expected values, rt and O , respectively. With these simplifying assumptions, we have

U1,2 =(U1)=(U2 ) =U2• WealsononnalizePt=l andEt=O.

The discounted value of the bank' s profit under cenainty is therefore:

(6)

The above expression is the gain the bank has for being able to buy securities with the .

costiess funds of its demand deposits, Le., the part that is not transferred to the Central

Bank as required reserves. The middle tenn occurs because of the increase in money demand from period 1 to period 2.

Under uncertainty, the bank's problem is the ooe of choosing the amount of bank

reserves it will hold from period 1 to period 2. Depending on the distribution of the stochastic variables r2 and E2, it may be optimal even for a risk-neutral bank to hold excess reserves. This is because if r2 is set by the Central Bank at too high a leveI, it may be the case that holding bonds from period 1 to period 2 may yield a nominalloss, Le., U1,2

>

U2 ,S A risk-averse bank would have more incentives to hold excess reserves. Although it may be optimal for the bank to hold excess reserves, we willasswne that the bank only holds required reserves. Severa! arguments justify this

assumption. The maio argument is that reserves are extremely expensive under

megainflation; the oPPOrtunity cost of holding excess reserves is the nominal interest rate, which under megainflation is of the order of at least 1,000 percent per year.6 To

S If there were more than ODe bank in lhe modeI. there couId be an additional reason to hold excess reserves. With severa! banks. each bank would monitor the other bank's actions to infer

whether they will be short oi reserve8 in lhe next period. If ODe bank believes thal lhe actiona oi its

competiton will prompt a shortage oi bank reserve8 in lhe open martet. signiflC8lldy raising interest rates 80 that UI J,>U2. it may hold euea reaeI vea 110 make a profit by aeUing lhe excess reserve8 110

other banks in period 2. It rernains a te)' necessary condition fex' this proc::ess to happen ihal lhe

Central Bant does not decide to provide üquidity to lhe banks short in

reserves.

i.e., thal lhe interest targeting procedure foUowed by lhe Central Bant aUows fex' lhe interest rale to rise.6 Even under lhe "normal" nominal rates, similar dfects seem to hold. Hodrick. Kocherlakota and LucM [1991] calibrate a cash-in-advance model to mimic US statistics. Their fmding is ihal lhe model prediclS esse1l1ially COllSlanl velocity.

Why a precaUlionary demtJItIJ for cash balances fails lO gellerate variatioll ill velocity ill lhe

..

1

10

be sure, when a bank holds excess reserves for a single day, it loses the ovemight

nominal interest rate. To be abIe to profit from this strategy, the real interest rate has

to rise enough to compensate the full ovemight nominal rale that was lost. Since under megainflation the inflation expectation component is by far the most important

one of the nominal rate, a very substantial ~crease of the real interest rate is required.

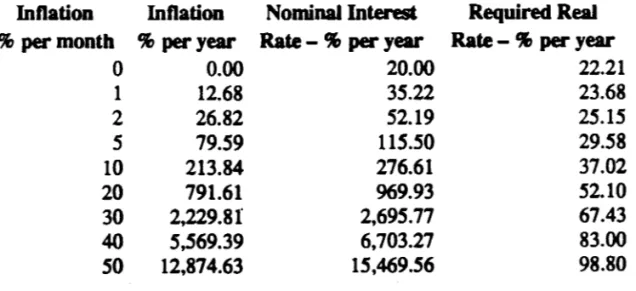

Table 2 perfonns a simple exercise to illustrate the above point. We asswne that the

bank has T-bills with ll-business-day maturity (half a month).7 The real interest rate is

20% per year. Table 2 computes the required yearly real interest rale that would have to hold for the following 10 days to compensate the bank from holding a single day of_ excess reserves. Oearly, under megainflation, the increases required may be too high

to be expected.

TABLEl

REQUlRED INCREASES IN THE REAL INTEREST RA TE IN ORDER TO

COMPENSATE A SINGLE DAY HOLDING EXCESS RESERVES

Inftaüon

Inftaüon

Nominal Interest

Required Real%

permonth

% peryearRate -

%per

yearRate -

%per

yearO 0.00 20.00 22.21 1 12.68 35.22 23.68 2 26.82 52.19 25.15 5 79.59 115.50 29.58 10 213.84 276.61 37.02 20 791.61 969.93 52.10 30 2,229.81 2,695.77 67.43 40 5,569.39 6,703.27 83.00 50 12,874.63 15,469.56 98.80

easll tUId illvestill' ill an illlerest-btarill' boNl. /11 tlais mt:H.k1. IM ~lIefit of tM former i.r lhol IM

moll~ provides IiqWdity services ill IM lIeD period. wltile IM boNl eQllllOt ~ eOllverted illto eOIlS,."",';oll lUltil two periods MIIU. Velocity varies WMII a,ellls Itold more easll IItan IItcessary for

e,,"elll expendinues ill some stlJles. Howtl'er.

if

IIOmiNJI illterest raieS are sujJicielllly 1ei,1I tUIdif

IMvariatioll ill IM mtIT,illal lUility of eOIlS,."",tioll cu:ro.r.r /IU",.e states is sujJicielltly .rmall. a,elllS

ecollOmize 011 easll balances tUId Itold just ellOu,1I money to eov". plll'CNues ill ali /IU",.e Slates.

7 Monetary policy in Brazil ia usually dane throulh purchueI and sales 01 28-day BBCs

•

,

11

The second argument to asswne zero excess reserves is that this simplification alIows

us to draw the highest possible profit as a function of the unknown T2, except when T2

gets so high that U u

>

U2

hold. Since we believe that the later condition is very unlikcly, such function will be very useful in analyzing lhe bank's problem. In otherwords, the no excess reserves solution is indced the rnaxirnimtg strategy under risk-neutrality when E,

~2/U,.2]~1.

The third argurnent is thatbariks

inItrazil

do not hold excess reserves.However, alI that was said depends aucially on the Central Bank's reaction function,

and ODe of its policy goals is to keep the financial system in good health. With such goal, the Central Bank may smoolhen interest rates to avoid capital losses for lhe

banks. If the banks know this criterion, they will not hold excess reserves,because

they will believe that the Central Bank will not alIow lhe interest rate to significandy rise.

nus

is then self-reinforcing, because ifbanks

do not hold excess reserves, the Central Bank will have then more incentives not to let steep increases in the interestrate to occur.

Note that in this rnodcl with ~

=

O lhe bank knows for sure that it will necd to tradeT-bills for reserves in period 2.

nus

is because positive inflation causes the nominal dcmand for dcmand deposits to grow. Since lhe Central Bank is the only supplier ofbank reserves, this amounts to lhe problcm of a monopolist facing a completely

ine1astic

demand curve, i.e., in the limit, lhe Central Bank may set lhe interest ratewherever it dcems fil We will

explain

short1y why lhe Central Bank never chooses toexercise this exttemc power.

When we assume no excess reserves, lhe bank's maximization problcm becomes a

trivial ODe. The bank invests everything in T-bills after fultilling lhe reserve

•

1

12

(7).

We may dccompose lhe bank's discountcd expected profit in fom sources, namcly:

1) The household's wealth: W1

-[J/U

1•2-Y(U

1.U

2)}U

1,2 represents the bank'sgain by perfonning the maturity transfonnation;

2) The (costless) demand deposits:

[

~

-(~

-I)+

M, . exp( lt) -(~

-I)l

U'3 repteSeI1ts lhe gains by investingthe costless demand deposits in periods 1 and 2, respectively;

3) The bank's required reserves:

r

(1 1

exp(1t»)1

.

.

l

Õ' M1 • - -+- -

+

exp(1t)J'

U1,2 represents the (negauve) gamsU

1•2U

2U

2by fulfilling lhe reserve requirements in period 1 (the first two tenns) and period 2 (the last two tenns);

4) The unexpected shock to money demand:

E, -[ exp (li:) .

(I

-li

>{

ik

-I)

l

UI.' tepn:sents lhe gains of a positive shock tomoney demand (demand deposits). The changes in the profit function of a shock to money dernand are lhe following:

,

,

13

4.1) the bank no longer has to pay interest from period 2 to period 3 on the

amount E, . exp(lt) , n:presenting a gain of E, -[ exp( 1t) -(

tt -) )]-

U'3 ; 4.2) the bank has to seU securities to fulfill reserve requirements ofÔ •

€z .

exp (n), representing a (negative) interest gain of:Expression (7) can be better interpreted if we use a Taylor approximation for l/U2

around l/Ut and then use the expectation operator (together with EI(r2 ) =rd

to-obtain EI

[l/u

2 ]=

(1/UJ· (l+a;J2

~

wherea~

is the conditional variance of r2 inperiod 1. We also assume that there is no shock to money demand, Le., E2 = O.

In

this case the discounted expected profit is:'" -f.

.[WI - MI - MI . (UI ·(l-Ô)· (exp(n)-1)]

(8), where '" is the discounted profit under certainty derived above. The Iast term inbrackets represents the discounted value of the increase in costless funds to the bank in

period 2 because of the increase in money demand (remember that here E2

=

O). Therefore, the expression in brackets represents the discounted value of the maximumamount of funds the households may wish to withdraw from their money market accounts in period 2.

In

other words, it represents the size of the funds withurunatched maturities. The whole expression teUs us that under uncertainty about

future interest rates, the discounted expected profit falls below the discounted profit under certainty. This gap is wider the largcr the interest variance is and the larger lhe

size of the funds with unmatched maturities is. Expression (8) teUs us that a very uncertain monetary

policy

could prompt lhe banks to leave the business of providingthe domestic currency substitute. However elegant it may be, expression (8) relies

,

14

argument under risk-neutrality. The argument that the Central Bank

has

its ability toconduct monetary policy, Le., to change the real interest rate, severely hampered by

the need of providing liquidity is much more robust.

Figure

3 exemplifies how the profitability of the bank is affectcd by inflation andmonetary policy (changes in the second period intcrest rate)~ The only source of the. bank's profit analyzed here is the investment in T-bills of costless demand deposits., With zero intlation (the injlation=O% line), the bank's profit is positive at the expectcd

second period real interest rate r2=20%. The profit

line

is negatively related to r2. Asinflation rises, the profit per unit of demand deposit rises, but the demand deposits falI.

Figure

3 shows the profit lines for injlation=791.6% (a monthly inflauon of 20%), andinjlation=12,874.6% (Cagan's hyperinflation threshold of 50%

per

month). The factthat the injlation=12,874.6% profit

line

lies below the injlation=791.6% ODerepresents the so-called Laffer curve in the present context. The households'

economize their real demand deposits (the tax base) to the point that banks profit

begin to

fall

despite the increase in the inflation late, and consequently, the nominal intcrest late (the tax rate) for a given real late. Df course, the exact shape of those profit curves would have to be empirically de1ennincd from lhe basic parameters of themodel The curves drawn in

Figure

3 are merely a vecy rough calibration.The point made by

Figure

3 is that even without uncertainty about the liquidity needsin period 2 (E = O), the bank' s profitability in the busincss of providing the domestic currency substitu1e is very sensitive to changes in lhe real interest late. This is also true for the nominal interest late. Therefore, similar effects to the ones obtained by

increases in the real intcrest rate are also obtained by unexpected increases in lhe

inflation late. Given the inflation pattcm displayed in

Figure

1 (intlation is usually rising), the uncertainty about rising inflation (not modcled here) compounds to theproblem, further constraining the monetary policy. One clcar evidence of how higher inflation leveIs induce higher risks. as well as higher profitability, in the banking

I

15 business

is

shownin

Table 3 (reproduced from Carneiro, Werneck, Garcia and Bonomo [1993]).TABLE3

MEAN AND VARIANCE OF~REST RATES (CJ, PER MONTH)

CORate Discount Rate Spread8

Pre-1980 Mean 2.62 3.65 1.00

1980-1985 Mean 7.53 11.06 3.27

Post-1985 Mean 18.51 24.60 4.76

Pre-1980 Standard Deviation 0.64 1.12 0.52

1980-1985 Standard Deviation 2.78 3.44 1.00

Post-1985 Standard Deviation 14.06 20.59 5.07

Table 3 displays lhe averages and standard dcviations for lending (discount) and

borrowing (CO) rates during three periods: lhe "low-inflation" period (1973-1979),

the high-intlation period wi~out economic shocks (1980-1985), and the extremely high-intlation period with economic shocks (post-1985). Table 3 shows c1early that in

the post-Cruzado era (see Figure 1) not oo1y lhe average spread increased, but its

variability became much greater. This result is consistent with the

familiar

mean-variance analysis: the extremely high and volatile inflation and lhe economic shocks tumed lhe Brazilian economy in a much riskier, and therefore more

profitab1c,

environmcnt for the banking business.

8 1be spread was computed with the correct compound intaelt arithmetic. This is why the

•

16

Nevertheless, the perceived risk cannot increase to the point that banks will no longer

want to be in the business of providing the domestic currency substitute. If the Central

Bank wants to keep alive the mcchanism that provides liquidity to interest-bearlng securities, it has to target interest rales with the objective of protecting the bank from

large capital 10sses.9

In

the model, this means that the Central Bank· will provide the bank with the necessary additional reserves in period 2 Without rmsing too muchinterest rates.IO

In

Brazil this is done by an automatic mcchanism, calledzerada

autom4tica,

which provides at the end of day the reservesbanks

need tofultill

theirreserve requirements.II The

zerada autom4tica

acts as an early discount window when it provides (cheap) reserves for the banks. As Diamond and Dybvig [1983] point out intheir modcl of bank runs and deposit insurance, the

discount window can, as a lentkr

of last resort, provith a service similar to thposit insurance. lt would

buybanJc asseá

with (money creation) tax revenlUs ( ... ) for prices greater than their liquidating

vallU.

Therefore, in spite of the smallness of Ml, the perception of liquidity is much larger. Banks trade an enormous amount of secmities to clear the daily transactions in the economy. Figure 4 (reproduced from Carneiro and Garcia [1993]) shows the amount

ofthe Central Bank's daily interventions in the open market. 1be negative values mean the sales of repurchase agreements, which is what the Central Bank does in times of

9 Derivaôve marketl have ewIved VfrJ rapidly in Bnzü (Carneiro. Werneck. Garcia anel

Bonomo [1993]). Tbere ia an intercst rale futures martet. which couId be used to hedge lhe interest

rale rist. However. such martet is not Iarp enougb to aUow lhe banb to hedge lhe interest rale rist

under megaintlation. Even if lhe futures martet MIe larger. tbere would be lhe question of wbo

would be willing to tJe. lhe intercst rale rist onda' a non-intercst-rale-targeting monetary policy

regime.

10 1be Central Bank couId raise lhe intercst rale in pcriod 3 widlout hanning lhe bant's profit. In practice, boweva-. lhe banb bolcl T -bilIs of several maaurities at any given mornent. 1berefore, lhe

staggered saructure of those securities constrain. lhe ~ poIicy at any given time. For an

alttmative model. see Lopes [1994].

11 1be zertlllo muom4tictl alao gives banb with excas reserves lhe Iast opportunity to buy

repun:hue agreements in arder not to incur in lhe bigh opportunity COIt of exc:ess reserves. Orle

would expect mat only une lide of lhe urtlllll muom4tictl would be used in any given day. depending

0Il whether lhe aure8* of banb is short or

lon,

on reaenea. However. it is not uncommon for lhe,

17 great uncertainty to avoid paying a prohibitive risk premium on lhe longer (one month)

maturity T-bill. The positive values represent Central Bank's purchases of govemment securities. The Central Bank is said to be undersold in the fonner case and oversold in

the later. The size of the Central Bank interventions(relatively to lhe monetary base or to the aggregate of bank reserves) is several times greater than th.at observed in countries with low inflation. Those constant intcrventions aimed at targeting the interest rate are the support of the provision of liquidity to interest-bearing securitic~

an~ ultirnately, what makcs possible for an economy to live with such small Ml.

The

mechanism just described provides an automatic way of increasing the money supply in

tine with expectcd inflation. as in the modcl of frictionless inflation described in

Patinkin [1993] for lhe Israeli economy before 1985.

By looking at Figure 3. one may doubt whether monetary policy is truly constrained.

After all. the profit tine the most sensitive to the interest rate risk is the inflation=O% one. Furthermore. however imprecise the calibration may be. the increases in lhe real

interest rate necessary to cause a negative profit seem very large to imply a constraint

to monetary policy.

In order to answer the first argumento one has to bear in mind what is the relative imponance of the profits modellcd here on a real bank' s aggregate profits. In

mcgainflationary economies, lhe banking sector relies very heavily on the profits created by non-intcrest-bearing demand deposits (Carneiro. Werneck. Garcia and Bonomo [1993]). Cysne [1993] calculatcs that 2% of lhe Brazilian GDP has been yearly transferred on average to lhe banking systcm in that fonn. Therefore. lhe

intcrest rate risk described above should affect a Brazilian bank much more than a US

bank, because lhe later does not depend so much on the profitability stemming from

non-interest-bearing demand deposits. It is clear that large increases in the interest rale

would affect the portfolio of any country's bank. However. large increases in real

interest raleS (of 10 or 20 percentage points) are unlikely to happen in countries with low intlation. In lhe Brazilian econorny. however. large increases in interest rates may

1

18

be necessary to achieve any meaningful economic policy goal. The next Section

analyzes this issue among others.

3. A few macroeconomic consequences oI the domestlc

currency substitute

3.1. The endogeneity of seignorage

One important consequence of the mcchanism of providing liquidity to intcrest-bearing

assets is that seignorage, which is representcd in the modcl of Section

2

approximatelyby the bank' s losses by holding required reserves, becomes endogenous. 12 The intcrest rate targeting pursued by the Central Bank precludes it from monetizing toa much lhe

economy in search for more seignorage. We can see this in the modcl of Section 2 by noting that an attempt to issue toa

many

reserves in period 2 would drive down theinterest rate,

r2.

While this would give lhe bolders of T-bills handsome profits, itwould also drive down lhe rate paid on lhe bank's money market deposits. If lhe

money market deposits may no longer be used as a mean to evade the inflation tax, lhe

households may look for other assets that could perfonn this function.

In

that case, theeconomy would undergo a typical currency substitution process.13

This is lhe basis for lhe claim in

Carneiro

and Garcia [1993] that in the domestic currency substitution regime, hyperinflation is the most Ii/cely outcome of an isolated (i.e., without fiscal adjustment) attempt by the Brazilian Central Bank to control12 Pastore [1993] also

men

to lhe endogeneity eX seignorage. although what fie means byendogenous seignorage ia quite different from what ia meant in this paper. Se

men

to monetary anelexchange policy rules (interest rale OI' real exchange rale targeting) that force lhe govemment to fully moneâze lhe fiscal deficit. therefore maldng seignorage eacIoIeDOUSly equal to lhe deficit. This ia observationally equivalent to GOl!!.'" seignorage modela (Bruno anel Fl8Cher [1990]. Blanchard

and Fl8Cher [1989]. p. 198). where lhe dynamics stem from extracting enough seignorage to finance

lhe ddicit.

13 A sequei to this paper wiD inc:orporúe a foreign a.uet to formally model lhe cumncy

•

19

money. What precludes agents from moving into foreign assets is lhe assurance of the

inflation protection and liquidity of the domestic currency substitute. An attempt by

lhe Central Bank to control the nominal amount of reserves in the system will certainly

make impossible for the banks to keep offering the domestic currency substitute .

Either the retums or the liquidity will have to be curtailed. Sure enough, interest rates

will rise and that would attract funds. The point is that without a crcdible fiscal

adjustment, the increase in interest rates necessary to keep agents from moving into . foreign currency and assets may be too high to be sustainable and believed. The

situation may be similar to speculative attacks against currencies, as in the September

1992 episode when the Sveriges Riksbank (lhe Swedish central bank) raised lhe

overnight marginallending rate to 500% per year, in an ultimately failed attempt to

keep the Iaona's parity (Svensson [1993]).

One does not see foreign currency circulating in Brazil in large proportions as in other

countries that lived through similar inflation rates precisely because of the domcstic currency substitute. The small M1 has in recent years providcd more than 3% of GDP

in seignorage revenues, as well as an additional2% of GDP share for the banks (Cysne [1993]). These figures, however large they may be, do not seem enough to justify a

hyperinflation.14 The amount of seignorage is endogenous, and may be extracted as

long as the domestic currency substitute is alive. With an already troubled fiscal

situation, lhe 1085 of seignorage revenue will ccrtainly make the fiscal dcficit significandy higher.15 Therefo~ if lhe Central Bank dccided in isolation to control

money, this could indeed

spark

a hyperinflation, in spite of very high interest rates. Thepoint here is ORe of credibility and sustainability.

14 Baud 011 available evidellce jromlWloricaJ causo ilseems IIfIII a persisle,., mtJlley-fiMIICed

deficil """' be about 10 lO 12 peru,., of GNP 10 geMrale a Ityperilljlatioll (Saehs and Larrain

[1993], p. 737).

15 Not lO mention that there would be an incn:ue in lhe budget deficit because of lhe reverse

Olivera-Tanzi effect.. This refen lO lhe fact that in Brazil fiIc:al revenues are beliewd 10 be beta

indexed lO infIation than outIays. 'l'lwzefore. infIation saabilizaünn. ceIem [KIIibtu. wouId inaease

I

,

20 In sununary, the dynamics of the Brazilian mcgainflation are nol driven bya necd of financing a given budget deticit through seignorage as it is usually asswned in models

of hyperinflation (Bruno and FIscher [1990]). The provision of lhe domestic currency

substitute slows down the currency substitution process that is always associated with hyperinflations. This makes possible for f:he government to collect seignorage for longer, although it has very little control on the amount it can collect

3~

Tbe lack of a nominal ancbor

The provision of the domestic curreflCY substitute endogeneize money supply,_

providing automatic sanction to any inaease in moncy demand. Price in(ZUCS

increase money demand, and, because of lhe interest targeting procedure, eventually

increase money supply, validaDng lhe

initial

price increases. Widespread indexationthen perpetuates the new inflation levei. Since lhe exchange-rate policy in Brazil

has

becn one of trying to flx the real exchange-rate, lhe system completely lacks a nominal

anchor. Any inflation rate, provided it is expected, may be an equilibrium. It is not

surprising that, as a consequence, inflation has exhibited lhe upward trend shown in

FIgure 1.

3.3. Tbe relative inetTectiveness

oI

bigb real interest rates

Real intcrest rates in Brazil have excecded lhe 20% leveI in 1993. Nevertheless, GDP

grew almost

S%

in real terms -whiJe intlation rose from lhe mid-20s to almost 40% permonth by lhe end of 1993. Thesc figures suggest a rather ineffective monetary policy.

The relative ineffectivencss of monetary policy to control intlation and/or to affect real

activity is due to two facton. The first ODe, which we wi1l not analyze in this paper,

has to do with the transmission

meclumism

of monetary policy in Brazil. Megainflationdestroyed many financiai rnarkets, most importandy the rnarket for long term financing

(Carneiro, Werneck, Garcia and Bonomo [1993]). Indexation proved to be all but a

I

21

Furthennorc. after many years of very high real intercst rates. most finns. finance alI their investments and working capital needs out of retained earnings. without resorting to bank credit (the stock market is of small importance in Brazil). The same applies to

consumer credito which is unbeara.bly expensive. The only aggregate demand item that

seems to be very responsive to increases in intercst rates is inventory.l6 Thercforc. the

stylizcd fact is that the real sector' s response to increasesin interêst rates is quite

small, also because of the income (wealth) effect associated with high real interest' rates when households and finns are net creditors. It should also be noted that therc is

a strong asynunctry, since the effects of a decrease in intercst rates are quite powerful

in boosting activity (and also intlation).

The second factor that accounts for the relative ineffectiveness of monetary policy is

the uncertainty about the relevant real interest rate. This is doe to two factors. With

megaintlation. the dispersion of differcnt price indices substantially increases. especially when intlation is accelerating. Also. agents' ability in forccasting intlation is

severely jeopardized. Therefore. when one looks at a series of ex post real intercst

rates. one may be quite far from the relevant ex ante real rates that guided the agents'

decisions.

The argument of a very disperse distribution of intlation forccasts does not explain

why agents would react less

in

the aggregatc to high interest rates. It only means that some agents willsee

a very high real rate where others may evensee

a negative one.They should still react acconling to their own perception of the real interest rate. Prudent behavior may help explain why a more disperse distribution of intlation

forccasts leads to actions consistent with a lower interest rate (higher expectcd intlation) then each agent' s own forccast. When faced with high future intlation

16 Even with invenlOrics. there secms 10 be a pervene effect fX hilh real interest rates on

infIation. Becauae fX lonl perioda fX hilh interest raleS. fim, reduce invenklriea 10 a minimwn.

'Ibelefore. when there ia a posiâve demand sbock. fim, tend to raiIe priceI quieta" than they wouId

•

,

22

uncertainty,17 agents may want to play safe, and choose a conservative (i.e., high)

intlation forecast. If this is indeed the case, a mean-preserving spread of each agent's inflation forecasts may lead to actions consistent with a higher inflation forecast.

We demonstrate that agents' perceptions of the real interest rate are very disperse

(because of the large dispersion oí intiationary expectations) by look:ing at two altemative sources. The first one is a collection of price indices. We show that the distribution of those indices is very disperse. The second ODe is the intlation futmes

market. We show that the forecasting errors of this market, even at very short horizons, are quite substantial. We now tum to the empirical evidence.

3.3.1. Different price indices

Figure 6 shows results from seven of the price indices most commonly used in Brazil.

They may differ in methodology, period of data collection and geograpbical coverage. Therefore, ODe could account for lhe diffcrences among the severa! indices.

Nevertheless, we contend that the large dispersion of the indices may be used to infer the dispersion of inflation forecasts. The standard deviatioos, computed each month from the seven rneasures of inflation, are very bigh.

Figure 7 shows the real rates that arise when we use lhe different price indices. The

bands for lhe real interest rate are quite large. If ODe takes lhe extreme view of always

considering lhe minimum real rate (for each month) as lhe relevant one, the average

real rates of 32.0% and 17.1% in 1992 and 1993, respectively, fali to 12.7% and

-0.0%. Therefore, the large dispersion among lhe

price

indiccs may lead to vcrydifferent perceptions of what lhe real interest rate is. Megainflation in this respect is

17 Dow. Simonsen anel Werlanl [1993] conc1ude that lUlCerttJÜlty (ÜI IM seue

0/

KnigltlJ.ratMr IIttJn in'dlionality is IM driving force btltiNlIM ezistence

0/

injflJtionary inertia anil IMnon-neutrtJlity 01 monttary policy. The prudent bebavior refmed abcwe may c:onceivabIy be modeled by

•

23

very di.fferent from hyperinflation, because in a hyperinflati.on all agents focus on the

exchaoge rate.

Figure 7 also shows the standard deviations. which are very high (left-hand-side scale).

Taking these estimates seriously, ODe could perfonn the following thought experiment.

Assume that the Central Bank decides to Send a clear signal of non-negative real rates.

Without further knowledge of the distribution of inflation forecasts. and asswning that agents are distributed homogeneously among the di.fferent forecasts, the Central Bank

would have to raise the real interest rate to twice the standard deviation in order send

a signal of a positive real rate to 7/8 of the population (using Olebyshev inequality)~

With ao average standard deviation of 13.3%18 for the period analyzed in Figure 7,

this would mcan that the Central Bank would have to target lhe real interest late

above 26.6%!

In

ex post tenns. one would observe a very high real rate. but thatresulted merely from lhe attempt to signal a non-negative real rate to most agents.19

3.3.2. The intlatiOll futures market

Figure 8 shows the results from lhe futores market for inflatiOll (OTN

I

BTN), for lheperiod it was allowed to operate. The tine is actual monthly

inflation.

whichis

measured by the left-hand-side scale in percent per month. The ClI'Ors refer to monthly

inflation percentage points. i.e., if a futores price implied ao inflation "forecast''20 of

18% per month whi1e actual inflatiOll was 20% per month, the error was 2% per

month. Aftcr computing lhe ClI'Ors for each day of lhe last 30 days for each contract

(the last month before inflatiOll was known).

we

calculate lhe average mcan absolute18 Each standard deviation ia computed with lhe seven obIc:rvaâonI of lhe real rate (one for

each price index) f(X' each month. Then we compute lhe arithmetic average standard deviation for aIl months.

19 I thank Marco Bonomo for sullestinl this thoupt experiment, and 1badeu Keller foi'

sUllestinl lhe use of Chebyshev inequality. (The use of this inequality assumes that lhe distribution ia

symmetric.)

20 lbe use of quota accounts for lhe fact that futurea pric:es are not neces..uy unbiased

predicton of spot prices (in lhe preaent cue. of intlation). Bias may ariIe for aeveral reasons (see

24

error and the square root of the mcan squared error along the month. These two

measures are the bars, with scale in the right-hand-side, also in percent

per

month. Note that those measures includc "forecasts" up to the day before inflationwas

actually anoounced. Figure 9 shows the same results when only the data for the first fortnight of the month is used, i.e., when the "forecasts" included range from 30 to lS

days before inflation was known.

Taking the square root of the mcan squared error (first fortnight) as a proxy for the

standard deviation, and using Olebyshev inequality, Figure 10 displays the

bands

where 7S% and 89% of the inflation forecasts should lie. Figures 8 to 10 corroborate

the point that inflation forecasts are very imprecise, even for very sOOrt horlzons.

In sununary, lhe ineffectiveness of monetary policy to control inflation and output may

be due to the two factors mentioned above, ~ly the very small response of

aggregate demand to increases in the real rate, and the extremely high dispersion of

inflation forecasts among agents. Such high dispersion refers both to the fact that agents canoot accurately forecast a given price indeXo and to the fact that different

agents care about different indices and lhe distribution of those indiccs is very disperse.

4. Concluslon

Sincc lhe mid-sixties Brazil undertook a rather deliberate attempt to live with inflation

by building a comprehensive system of inflation indexation. Inflation indexation

was

aimcd at reducing some of lhe welfare costs of inflation, and was lhen widcly thought as a good solution21 The othel' key factor

was

lhe provision of liquidity tointerest-21 AI least IHfore IM /irst oil sltock iIl1973-74. wilkspread illllutuioll wtJS oftell prtlised tIS ti

secolld IHst 10 price sttJbility. 11 appetJTed 10 millimiu IM welfare Iosses ctlllSed by ;'ajltJtioll. Amoll'

olMr vinues. wilkspread esctútJtor cltJJues wouId

mil.

colltrtlCU i_pe_'" of injltJtiolltlryOI

25

bearing assets, Le., the supply of substitutes to M 1 that were protected from the

inflation

taxwithout giving up the liquidity. Carneiro

andGarcia

[1993]suggest the

name

domestic currency substitute for

thisclass of financiaI instruments because they

slow down the usual process of currency substitution associated with hyperinflations.

This

papermodels

theworking mechanism of the domestic currency substitute, as

wellas analyzes a few of its macroeconomic consequences. The most important

macroeconomic consequence

isthat

thismechanism allows the economy to sustain for

quite a long

timean extremely high inflation leveI without jwnping to hyperinflation,

although the economy slowly drifts toward hyperinflation

(seeFigure

1).Carneiro

andGarcia

[1993]suggest the name megainflation for

thisprocesso

The modcl of the domestic currency substitute (Section

2)shows that the provision of

liquidity to interest-bearing assets severely constrains

thernonetary policy.

This isbecause the very existence of the domestic rnoney

(M 1)depends on the supply of the

domestic currency substitute. Abrupt rnovements in interest rates, as those that would

happen

ifthe Central Bank decided to target a nominal rnonetary aggregate, would

make impossible for the

banksto keep offering inflation protection with ovemight

liquidity.

Asa resulto the rnonetary policy becomes passive,

andthe rnonetary

basegrows rather automatically with intlation.

In Section 3,

lheconsequences of this automatic monetization

are

analyzed. Automatic

rnonetization together with tbe

lackof other

nominal anchors (exchange rate) means

that

lheeconomy

hasan

undetennined cquilibrium.H a given inflation rate

isexpected

to

happen, it

willhappen.

The other macroeconomic consequence of

thedomestic currency substitution regime

is

that the dynamics of megainflation

are not driven

by theattempt of the govemment

tlimilUllt CIIIy Itmporary injlQtion-output trtJJit-ojf. tJNl ali IM IUIcomforl4blt side tfftCtl of

CIIIIi-injlQliolfllT'Y policies. In facl llIiI wa.r Milton Fritdnttlla', ctntral

.,IIIMIII

in lIiI tnlluuitulic dtfonsc•

26

to collect seignorage by printing more money, as it is usually asswned in models of hypcrinflation (Bruno and FlSCher [1990] and B1anchard and FlSCher [1989], p. 198).

Note, however, that

this

does not imply that the Brazilian rnegainflation was notcaused by a fiscal imbalance. At

this

point, we are not abIe to present a full-blowngeneral equilibrium model that explains how rnegainflation originated and evolved.

~

What we are concemed with in

this

paper is the dynamics implied by the domesticcmrency substitute once rnegainflation is already running. The provision of the

domestic cmrency substitute slows down the cmrency substitution process that

is

always associated with hyperinflations.

This

makes possible for the govemment tocollect seignorage for longer, although it has very little control on the amount it can collect. With the domestic cmrency substitute, the Central Bank cannot issue money to pay for the fiscal outlays. H it did that, the market for bank reserves would be in excess

supply of reserves, and interest rates would falI. Given the smallness of bank reserves,

any significant increase in the deficit that needed to be tinanced through seignorage would drive interest Iates down by a

large

amount.This

drop in interest rate willeventually be reflected in the rates paid by banks on the money market accounts,

jeopanlizing the ability of the domestic cmrency substitute to

remain

competitive withforeign cmrency. Therefore, all increases in the fiscal deficit must be financed through

debt and not through seignorage.

On lhe other side, if the Central Bank decided to make the bank reserves grow at a

much smallcr rate that inflation, it could risk to sparlc a hyperinflation.

This

could happen because in a regime where lhe Central Bank no longer is concemed withsmoothing the interest Iate, it would probably vary so much as to preclude

banks

from offering an asset that could at the same time protect from inflation and offer ovemightliquidity. The economy would then move to a path of massive cmrency substitution,

Le., a hypcrinflation. Whether or not lhe very high interest Iates that would emerge from

this

liquidity squeeze would sustain the demand for dornestic govemment securities, and consequently to lhe domestic money, wouJd depend on lhe fiscal"

27

situation. Without a previous credible

fiscal

adjustment, it is very unlikely that thegovemment could sustain an interest rale high enough to avoid the currency substitution process that the demise of the domestic currency substitution regime would entail.

The last issue analyzed in Section 3 is

lhe

effccts of very high real rates on inflationand output. The stylized fact is that very large and positive real interest rales are quite

ineffcctive to lower inflation and output. We suggest two ways to explain

this

one wayineffcctiveness of high real interest rales. The first link, which is next in the research

agenda, is the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. Aft.er a long period of

megainflation and high real raleS, most households and finns already refrain

from

going into debt. Therefore, further increases of interest rales face a very

inelastic

dernand for credit, whilc decreases face a rather elastic ODe. The second link is the

excessive dispcrsion of inflation forecasts.

nus

is doe both to the inability of agents to accuratcly forecast inflation and to the existence of several price indices, with adistribution whose dispersion grows with intlation. U nder high uncertainty about future intlation, agents may behave prudendy and act accordingly to a more

conservative (i.e., higher) estirnate of intlation.

nus

would mean that very high ex post real rates would not have a very large effect in aggregate demandThe very nature of the

domestic

currency substitution regime requires a positive exante real rale.

nus

is what ultimately precludes agents from going into foreign currency and assets. When faced with a very disperse distribution of price indices, theCentral Bank may be forced to

raise

its expected real rale to very high leveIs only to send a clear signal of non-negative real interest ratcs to most agents.When inflation reaches the current extremely high level (5500%), it is also highly

volatilc, greatly jeopardizing economic activity. Aftcr rnany years of very high intlation, it is becoming clear to most Brazilians that the costs of coping with inflation

•

•

28

are

highcr thanthose of fighting il

22The lessons of the Brazilian case are important

for countrics

likeRussia, which may en1Crtain

lheelusive possibility of an easy way out

of fiscal and monetary controls

tofight intlation.

22 Simon8en and Cysne [1994] estimate that lhe current welfare

cosas

m

infIation hover around•

29

References

E. Bacha, " Políticas de estabilização em países em desenvolvimento: Notas sobre o

caso brasileiro", mimeo, Dept. orEconomics, PUC-Rio, 1993.

Banco Central do Brasil, Boletim do Banco Central do Brasil, 1994.

Banco Central do Brasil, Brazil Economic

Program,

39, 1993.o.

Blanchard and S. Fischer, Lectures 011 Macroeconomics, The MIT Press, 1989.M. Bruno and S. Fischer, " Seigniorage, Operating Rules and the High Inflation Trap,"

Quarterly Joumal or Economics,

1990.

E. Cardoso, "Inflation and Poverty," Worldng

Paper,

NBER, 4006, 1992.D. Carneiro, R. Werneck, M. Garcia and M. A. Bonomo, "Strengthening Brazil's

Fmancial Economy," Working

Paper,

Inter-American Development Bank, 142, 1993.D. Carneiro and M. Garcia, " Capital Rows and Monetary Control under a Domestic Currency Substitution Regime: The Recent

Brazilian

Experience," WorkingPaper,

PUC-Rio, 1993.

R.

Cysne. 1993. Imposto Inflacionário e TransfeIências Inflacionárias no Brasil.Workinl

Paper,

FGV-RJ. 1993.D. Diamond and P. Dybvig, "Bank Runs. Deposit Insurance. and Liquidity," Joumal

orpolitical Economy, 91, 1983 .

R. Dombusch and M. Simonse~ eds, InIlatiOll, Debt and Indexation, The MlT Press, 1986.

J. Dow, M. H. Simonsen and S. WC2'lang, " Knightian Rational Expectations,

"

30 M. Garcia. 1991. Thc Formatioo of Inflatiop Expcctatiops in Brazil. Ph.D.

dissertatioo, Departmcnt of Economics, Stanford University.

M. Garcia, " Política Monetária e Fonnação das Expectativas de Inflação: Quem Acertou Mais, o Governo ou o Mercado Futuro?," Pesquisa e Planejamento

EConôDÜCO, 22,475-500, 1992.

M. Garcia, " The FlSher Effect in a Signal Extraction Framework. The Recent

Brazilian Expcrience," JoUrnal ofDevelopment EConomics, 41, 71-93, 1993.

R. Hodrick, N. Kocherlakota and D. Luéas, " The Variability of Velocity in

Cash-in--Advance Models," Joumal ofPoIitical Economy, 99,1991.

F. Lopes, " Moeda Indexada e Controle Monetário," mimeo, 1994.

A. Pastore, " ~ficit Público, a Sustentabilidadc do Crescimento das Dívidas Interna e

Externa, Senhoriagem e Inflacao: Uma Análise do Caso Brasileiro,"

mimco,

1993.D. Patinkio, " Israel's Stabilizatioo Program of 1985, Or Some Simple Truths of

Mooetary Theory," Joumal ofEconomic Perspectives, 7, 103-128,1993.

1. Sachs and F. Lamün, Macroeconomics in tbe Global EConomy, Preotice Hall,

1993.

M. H. Simonsen and R. Cys~ " Welfare Costs of Inflation: The Case for Intcrest

Bearing

Money

and Empirical Estimatcs For Brazil," WorkilllPape.",

FGV-RJ,1993.

F. Sturzenegger. 1991. Essl)'S op Inflatiop apd Fmancial Adaptatiop. Ph.D.

dissertation, Departmcot of Economics, MIT.

L. Svensson, "FlXed Exchange Rates as a Means to Price Stability: What Have we ~" Working

Paper,

Institute for Intemational Economic Studies,~

-rrI ~ -M ~ -'ll JO f1O::> ~ -~ -IJOUOJ~

-'QWWOS Q\ 00 Q\ -00 00 Q\ -~ .~gr

-00 Q\ -~ Q\ -V'I 00 Q\ -~ Q\-~

-~ -Ôq

FIGURE 2

TIIE

BANK1S

CASH FLOW

PERIOO 1

PERI002

M1 L!Ml

I\~M~

Ml....

-RI

1

1

RI BP1,2

Ml

MMl

R

2

W'BP.l

-

U.

R 82

2

PERl003

PROFIT

M2

MM2

~

..

t 86'0

I

96'0I

W;'O ~6'0I

ôOI

8S'0-98'01

~ "!"~

•

r--~S' ~ oq N -8' 118

8'/0.=

:t"Ot!

z

c: 'O -O 'd...

,L'O-=

~

e

~

~

'O 99'0 ~ ,~to:

~

~9'0 " ~ ~<

•

-I

=c ~ ~ -"! l::iC!

-u

I

0\ ~ª

~

I

s

rrI=

..

.~~

I

vt!

~

=c c:1

-o

1

'd li:~

ct

~

I

~'o

~o

1

o

I

I

l::iCI

to

fIJI

Q". ~o

~I

K'O~

I

~to=

,to

-I

, ~~

.

8l'0íl'

I

, , 9t"0.g

E-.

I

n'0t!

.

l'to

c:-I

.

-,ro

ã

,I

.

SI'O~

.

I

.

91'0.

.

tl'O ,I

zl'OI

1'0.

80'0I

, 90'0§

I

;0'0~

m"o

·ã

<11 ~ ('\""'

-~ Q ~-""'

('\!

Q -Qq

-Q Q Q qq

q ~ SIIJCUdi

U)FIGURE 4

Oversold (+) and Undersold(-)

300% 200% 100% , I

I

jaII6-' I I I ( ) t , . . • I. I. 'JI1o'IR I I ' .'1f.D.i II - 1" II11

J

-100%J

.. -200% #. -300% -400% -500%Source: Carneiro and Garcia (1993)

i

,~~

,

-

~

N~

-

N ',\

, - - OversokVTocal Bank Reserves - - - Oversold/Monetary Base

_J

ff'\