ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Journal

of

Hazardous

Materials

jou rn a l h om ep ag e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / j h a z m a t

Batch

and

fixed-bed

assessment

of

sulphate

removal

by

the

weak

base

ion

exchange

resin

Amberlyst

A21

Damaris

Guimarães

∗,

Versiane

A.

Leão

Bio&HydrometallurgyLaboratory,DepartmentofMetallurgicalandMaterialsEngineering,UniversidadeFederaldeOuroPreto,CampusMorrodoCruzeiro, s.n.,Bauxita,OuroPreto,MG,35400-000,Brazil

h

i

g

h

l

i

g

h

t

s

•AmberlystA21(weakbaseresin)wasappliedforthefirsttimeinsulphateremoval. •Itisacomprehensivestudyofthemainaspectsofsulphateadsorption,neverdonebefore. •SulphateadsorptionprocessbyAmberlystA21isfastandfeasibleinacidmedium. •Efficientsulphateelutionwasobtainedusingsimpleandaccessibleconditions.

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received20February2014

Receivedinrevisedform4July2014

Accepted26July2014

Availableonline13August2014

Keywords:

Sulphateremoval

Sorption

Ionexchange

AmberlystA21

Weakbaseresins

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

ThispaperinvestigatedsulphateremovalfromaqueoussolutionsbyAmberlystA21,apolystyreneweak baseionexchangeresin.BoththepHandinitialsulphate concentrationwereobservedtostrongly affectsorptionyields,whichwerelargestin acidicenvironments.Working underoptimum opera-tionalconditions,sulphatesorptionbyAmberlystA21wasrelativelyfastandreachedequilibriumafter 45minofcontactbetweenthesolidandliquidphases.Sorptionkineticscouldbedescribedbyeither thepseudo-firstorder(k1=3.05×10−5s−1)orpseudo-secondordermodel(k2=1.67×10−4s−1),and boththeFreundlichandLangmuirmodelssuccessfullyfittedtheequilibriumdata.Sulphateuptakeby AmberlystA21wasaphysisorptionprocess(H=−25.06kJmol−1)thatoccurredwithentropyreduction (S=−0.042kJmol−1K−1).Elutionexperimentsshowedthatsulphateiseasilydesorbed(∼100%)from theresinbysodiumhydroxidesolutionsatpH10orpH12.Fixed-bedexperimentsassessedtheeffectsof theinitialsulphateconcentration,bedheightandflowrateonthebreakthroughcurvesandtheefficiency oftheAmberlystA21inthetreatmentofarealeffluent.Inallstudiedconditions,themaximumsulphate loadingresinvariedbetween8and40mg(SO42−)mL(resin)−1.

©2014ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved.

1. Introduction

Whenoxidizing conditions are present,sulphate is the pre-dominantsulphurspeciesinliquideffluentsassociatedwiththe processingsulphur-ladenrawmaterials[1,2].Highsulphatelevels inwaterandwastewatersarerelatedtotheoccurrenceofpiping andequipmentcorrosion,and,whensucheffluentsaredischarged intotheenvironment,theymayincreasetheacidityofbothsoils andbodiesofwater[1,3].

Amongwastewaterscontaininghighsulphateconcentrations,

acidminedrainage(AMD)isoneofthemostimportant.AMDis

generatedwhensulphidemineralsareoxidizedinthepresenceof

∗Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+553135591102;fax:+553135591561.

E-mailaddress:guimaraes.damaris@yahoo.com.br(D.Guimarães).

waterandoxygen,eitherwithorwithouttheaidofbacteria.This acidicsolutionactsasaleachingagentfordifferentminerals, pro-ducingadrainagerichindissolvedmetals,whichcanrendernatural waters unsafefor use,even after miningactivitieshave ceased

[4]. Highsulphate concentrations indrinkingwater cause taste alteration and, when the sulphate content exceeds 600mgL−1, diarrhoea[2].Becauseoftheseadverseeffectstohumanhealthand theenvironment,miningcountriesusuallysetlimitsforsulphate concentrationsinwatersandwastewatersrangingfrom250mgL−1 to500mgL−1[2,5].

Sulphate emissions can be controlled by combinations of

differenttechniquessuchaslimeneutralizationandgypsum pre-cipitation, reverse osmosis, electrodialysis and adsorption [1]. Althoughtheapplicationofadsorptionisoftenlimitedtothe pol-ishingstepofwastewatertreatment,itisapromisingmethoddue toitsabilitytoreducesulphateionconcentrationstoverylowlevels

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.07.071

[6].Moreover,itsrelativecostcanbereducedbyselectinga suit-ableresinandworkingunderconditionsthatmaximizeadsorption andalsofacilitateregeneration.Sulphateremovalbyshrimp peel-ings[7],modifiedcellulosecontainedinbothsugarcanebagasse

[8]andricestraw[9],coconutpith[10],limestone[11]and mod-ifiedzeolites[12]havebeenproposed.Fengetal.[13]deviseda processforAMDtreatmentcomprisedofmetalprecipitationand sulphatesorptiononionexchangeresins.Nevertheless,a funda-mentalassessmentofsulphatesorptionmechanismsisyettobe carriedout.Withinsucha context,thepresentstudysoughtto investigatetheutilizationofAmberlystA21,aweakbaseresin,for sulphatesorptionbecausethismaterialconferstheadvantageof easyelutionviapHshift.

2. Experimental

2.1. AmberlystA21resin

AmberlystA21isa weakbase(tertiaryamine)macroporous

polystyreneresin withanexchangecapacity of1.25eqL−1 [14]. Priortotheexperiments,theresinwassievedusingTylersieves,

and a particle size range between 0.71mm and 0.84mm was

selectedforallexperiments.Sampleswerekeptunderwaterfor atleast40hbeforeuseintheexperiments.

2.2. Batchsorptionandelution

TheinfluenceofbothpH(2,4,6,8and10)andinitialanion concentrationonsulphateuptakewasstudiedbyplacing1mLof hydratedresin incontactwith100mLofsodiumsulphate solu-tionswithSO42−concentrationsrangingfrom100to1200mgL−1. Theexperimentswereperformedover5h,duringwhichthe sys-temwasstirredat180min−1 whiletemperature(34◦C,50◦Cor

70◦C)andsolutionpHwereconstant.Attheendofthe

experi-ments,thesampleswerefiltered,andthesulphateconcentration intheaqueousphasewasdeterminedbyICP–OES(Inductively Cou-pledPlasma–OpticalEmissionSpectroscopy).Sulphateloadingsin theresinsweredeterminedbymassbalance.

Thekineticofthesorptionwasalsostudied.Inthisstep,5mL

of hydrated resin were mixed with 1L of solution containing

160mg(SO42−)L−1 at28±1◦CandpH4,whichwerekept

con-stantthroughouttheexperiment.Thesystemwassampledevery

5mininthefirsthour,every10mininthesecondhour,andat140, 160,180,210,240and360min.Sorptiondatawerethenfittedto pseudo-firstorder,pseudo-secondorderandintraparticlediffusion models[15].

Thepseudo-firstordermodelassumesthatthesorptionprocess isreversibleandreachesequilibrium.Thismodelisrepresentedby Eq.(1),wherek1 istheoverallrateconstantforthepseudo-first ordermodel,tistimeandUtthefractionalattainmentof equilib-rium.UtisobtainedbyEq.(2).Suchamodelcanonlybeapplied todatafromtothelowerpartoftheresinloadingcurve;i.e.,the modeldoesnotapplytoequilibriumdata[15].

ln (1−Ut)=−k1t (1)

Ut= q

qeq

= Co−C

Co−Ceq (2)

Thepseudo-secondordermodel(Eq.(3))wasproposedbyHo andMcKay[18]todescribesorptionprocessesinwhichthe rate-determiningstepisthesorptionreaction.In thisequation,k2 is therateconstantofthepseudo-secondordermodel,andqt and

q∞arethesulphateloadingachievedattimetandatequilibrium,

respectively.

qt= tk2(q∞) 2

1+tk2q∞

(3)

TheintraparticlediffusionmodelproposedbyWeberand Mor-ris[19]isvalidifadsorbatediffusionintheliquidfilmistheonly controllingstepoftheprocess.ThismodelisdescribedbyEq.(4), inwhichkipistherateconstantofintraparticlediffusion,andCis aconstantrelatedtothethicknessoftheboundarylayer.

q=kip(t)1/2+C (4)

Sorption equilibrium was investigated using adsorption

isothermsproduced atdifferent temperatures,which enabled a

thermodynamicanalysisofsulphatesorption.Theisothermswere producedbymixing1mLofhydratedresinwith100mLofsodium sulphate solutions whose initialsulphate concentrations varied between30mgL−1 and1800mgL−1.Eachsystemwasstirredat 180min−1,pH4andatemperatureof34◦C,50◦Cor70◦Cuntil

equilibrium wasreached.The aqueousphase wassubsequently

separated from the solid phase, and the residual aqueous

sul-phateconcentrationwasdeterminedbyICP-OES.Resinloadingwas determinedbymassbalance.Equilibriumdatawerethenfittedto theFreundlichandLangmuirmodels[14]priortothermodynamic analysis.

TheLangmuirmodel(Eq.(5))wasoriginallydevelopedto rep-resentmonolayeradsorptiononidealsurfaces.Itassumesthatthe heatofadsorptionisindependentofsurfacecoverageandissimilar tothatobservedinchemicalreactions.Furtherassumptionsare:(i) thereisalimitedandmeasurableareaforadsorption;(ii)the mono-layerisonemoleculethick;and(iii)adsorptionisreversible,and equilibriumconditionsareattained[6].Conversely,theFreundlich isotherm(Eq.(6))isanempiricalequationthatdescribesnon-ideal adsorptionprocesses.Itassumesheterogeneoussurfacesand mul-tilayeradsorption[20],resultinginanexponentialdistributionof theheatsofadsorption[6].

qeq=qmaxbCeq

1+bCeq (5)

qeq=Kf

Ceq 1/n(6)

InEqs.(5)and(6),qeqistheresinloadingatequilibrium,Ceqis theequilibriumconcentrationoftheadsorbateinsolution,qmaxis themaximumloading,bisaconstantrelatedtotheaffinitybetween theresinandtheadsorbate,Kfisthecapacityfactor,andnisthe intensityparameter[6].

Athermodynamicanalysisuseddataproducedfortheinitial sulphateconcentrationof300mgL−1wascarriedouttoassessthe influenceoftemperatureonthesorptionprocess.Equilibrium con-stant(Keq)valuescorrespondingtothesorptionprocessdeveloped atdifferenttemperaturesweredeterminedutilizingEq.(7):

Keq= qeq

Ceq (7)

Theequilibriumconstant, aswrittenin Eq.(7),is alsocalled thedistributioncoefficient(KD)[24–26].AfterobtainingKeq,the enthalpy(H)andentropy(S)ofsulphatesorptionwere deter-minedfromthevan’tHoffequation(Eq.(8)),andtheGibbsfree energywascalculatedbyEq.(9).

lnKeq=−H RT +

S

R (8)

G=−RTlnKeq (9)

In Eqs. (8) and (9), R is the universal gas constant

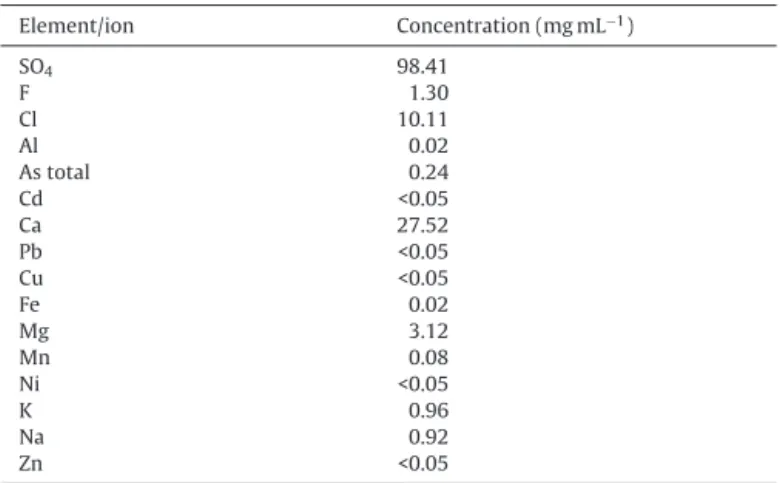

Table1

Compositionoftheindustrialeffluentusedexperimentally.

Element/ion Concentration(mgmL−1)

SO4 98.41

F 1.30

Cl 10.11

Al 0.02

Astotal 0.24

Cd <0.05

Ca 27.52

Pb <0.05

Cu <0.05

Fe 0.02

Mg 3.12

Mn 0.08

Ni <0.05

K 0.96

Na 0.92

Zn <0.05

SulphateelutionfromAmberlystA21wasassessedbymixing 100mLofsodiumhydroxidesolutions(atpH10andpH12)with 1mLofpre-loadedresin(10.4mg(SO42−)mL(resin)−1).Thesystem waskeptunderagitationfor24hat30◦C,andthefinalsulphate

concentrationintheaqueousphasewasdeterminedbyICP–OES priortocalculatingresinelutionefficiencies

2.3. Fixed-bedexperiments

Sulphateadsorptioninfixed-bedcolumnswereperformedin ordertoinvestigatetheeffectsofconcentration,bedheightand flowrateonbedloading.Differentvolumesofresin(0.71–0.84mm particlesizes)weretransferredtoaglasscolumn(13mm diam-eter×142mmheight)toproducedifferentbedlengths,Z(6cm, 9cmand12cm).Afterloading,distilledwaterwaspassedthrough thecolumn(60min)toremovefineparticlesthatcouldhavebeen loadedinthecolumn.Thecolumnwasfedupwardsbyperistaltic pumpssothatanypreferentialpathwayforthesolutionwouldbe avoided.Theflowrate(Q)wasvariedbetween10and20mLmin−1. Sampleswerecollectedregularlyfromthecolumneffluent.The sul-phateconcentrationsinthesesampleswereanalysedbyICP–OES. Theinlet sulphate concentration(C0)rangedfrom55mgL−1 to 160mgL−1,andtheanionloadingontheresinwasdeterminedby massbalance.TheexperimentswerecarriedoutatapHof4.0and atemperatureof28±1◦C.

ToassesstheefficiencyofAmberlystA21inthetreatmentofa realeffluent(fromtheminingindustry),adsorptionexperiments wereperformedina fixed-bedcolumn.The compositionofthe acidiceffluent(pH3.2)ispresentedinTable1andtheexperiments werecarriedoutat25±1◦C,usingabedheightof9cm,whichwas

fedataflowrateof10mLmin−1.Immediatelyafterloadingthebed, itwaselutedfor3hwithapH12sodiumhydroxidesolutionata flowrateof10mLmin−1.Thesampleswerecollectedinintervals of10minandthechlorideandfluoridecontentweredetermined

byionchromatography(Metrohm).

3. Resultsanddiscussion

3.1. Batchexperiments

AscanbeseeninFig.1,sulphateloadingsinAmberlyst A21 weresignificantlyreducedasthesolutionaciditydecreased.This outcomewasexplainedbythepresenceoftertiaryaminegroups, whichmustbepositivelychargeinordertobindsulphate(Eq.(10)). Therefore,theconcentrationofprotonatedaminegroupsincreased with increasing acidity, resulting in greater sulphate loading (Eq.(11)).Fig.1 also indicatesthat increasingthe initialanion

2 4 6 8 10

5 10 15 20 25 30 35

(a)

Su

lpha

te

c

on

c.

in

th

e

re

si

n

(m

g

m

L

-1

)

pH

Initial Sulpha

te con

c.

100 mg L

-1300 mg L

-1700 mg L

-11200 mg L

-12 4 6 8 10

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35

Su

lpha

te

c

on

c.

in

th

e

re

si

n

(m

g

m

L

-1

)

(b)

pH

Initial Sulpha

te con

c.

100 mg L

-1300

mg L

-1700

mg L

-12 4 6 8 10

0 5 10 15 20 25 40 42 44

Su

lpha

te

c

on

c.

in

th

e

re

si

n

(m

g

m

L

-1

)

(c)

pH

Initial Sulpha

te con

c.

100

mg L

-1300

mg L

-1700

mg L

-1Fig.1.EffectofpHonsulphatesorptionbyAmberlystA21resinat34◦C(a),50◦C(b)

and70◦C(c).Experimentalconditions:1mLofhydratedresin,100mLofsolution

andstirringrateof180min−1.

concentrationresultedinlargersulphate loadingsonAmberlyst A21.Conversely,sulphateloadingswereslightlyreducedathigher temperatures;thiswillbefurtherdiscussedduringtheanalysisof theeffectoftemperatureonsorptionequilibrium.

R–NH3(resin)+H2O⇆RNH4+(resin)+OH−(aq) (10)

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 0

3 6 9 12 15

k = 1.67

x 10

-4min

-1q

eq= 13

.9 mg mL(res

in)

-1R

2= 0.96

Time (min)

q

t(m

g (S

O

4 2-) m

L(r

es

in

)

-1

)

Fig.2. Loadingsulphate(qt)infunctionoftimeandfitofpseudo-secondorder

modelfromadsorptionessaysbyAmberlystA21.Experimentalconditions:5mLof

hydratedresin,1Lofsodiumsulphatesolution(150mg(SO42−)L−1),at28±1◦C,pH

4,stirringrateof200min−1.

ThepH4 wasselected for furthersulphatesorption studies

becausethis pHis encounteredinmanyAMDsites.Workingat

thispH,Fig.2 depictstheprofileof thesulphateconcentration intheresinasafunctionoftimeinabatchstudy.Thesorption process,whichwascomprisedoftwodifferentstages,resin pro-tonation(Eq.(10))andsulphatesorption(Eq.(11)),wasrelatively fast,attaininganequilibriumconcentrationof11.6mgmL(resin)−1 innearly45min.

The kinetic data were fitted to pseudo-first order,

pseudo-second order and intraparticle diffusion models. Among these

models, only the pseudo-second order model showed a good

fit to the experimental data and described all thedata gener-atedinthekineticexperiments.Thus,itcanbeinferredthatthis

model describes the adsorption of sulphate by Amberlyst A21

resin.AsshowninFig.2,thepseudo-secondorderrateconstant was1.67×10−4s−1andthetheoreticalequilibriumsulphate load-ing(q∞)was13.9mgmL(resin)−1,which isconsistentwiththe

experimentalvalue(11.6mgmL(resin)−1).Instudiesofsulphate adsorptionbyanothertypeofadsorbent,Oliveira[12]investigated theadsorptionof sulphatein zeolites functionalizedbybarium salts.Inthiscase,theprocesswasdescribedbythepseudo first-ordermodelwithanoverallrateconstantof0.4s−1.

Subsequently, sorption equilibrium was investigated utiliz-ingisotherms produced at differenttemperatures and fittedto both Langmuir(Eq.(5))and Freundlich (Eq.(6))models.Fig. 3

presentsthe fittingsof the experimentaldata to theLangmuir

0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400

0 5 10 15 20

Aqueou

s sulpha

te con

c.

(mg L

-1)

Su

lpha

te

c

on

cen

tr

a

tion

(m

g

m

L

(r

es

in)

-1

)

34o

C

50o

C

70o C

Fig.3.AdsorptionisothermsfittedtoLangmuirmodel,constructed withdata

obtainedfromessayscarriedoutindifferentconditionsoftemperature,pH4and

stirringrateof180min−1,withtheAmberlystA21resin.

Table2

AdsorptionisothermsparametersofLangmuirmodelobtainedatdifferent

temper-atures,pH4andstirringrateof180min−1,withAmberlystA21resin.

Temperature Langmuir

Parameters R2

34◦C q

max=16.18 0.83

b=0.16

50◦C

qmax=12.78 0.98

b=0.15

70◦

C qmax=10.11 0.92

b=0.06

0.0029 0.0030 0.0031 0.0032 0.0033

3.6 3.8 4.0 4.2 4.4 4.6 4.8

Y=3014

,25

*X-5,02

R

2=0,99

1/T

ln

(K

eq

)

Fig.4.van’tHoffplotforsulphatesorptiononAmberlystA21.

equationat differenttemperatures(34◦C, 50◦C and 70◦C); the

Langmuirisothermcanbeutilized todescribesulphate adsorp-tionbyAmberlystA21,withqmaxvaluescloseto15mgmL(resin)−1 (Table2).Theobservedbconstantvalues,alsolistedinTable2, gen-erallydecreasedwithincreasingtemperature.Asthisconstantis relatedtotheaffinitybetweensulphateandresin,itcanbeinferred thattheaffinitydecreasesastemperatureincreases[6].Sorption datawerealsofittedtotheFreundlichmodel,however,agood fit-tingwasnotobservedinthiscase. Basedontheanalysisofthe

R2 values,itcanbestatedthatsulphateadsorptioninAmberlyst A21isdescribedbytheLangmuirmodel.Thisway,thesurfaceof theloadedresiniscomposedofamonolayerofsulphateanions. SimilarresultswerealsoobservedbyHaghshenoetal.[21]forthe

ionexchangeresinLewaitK6362,byNamasivayamandSangeetha

[10]usingZnCl2activatedcarbonproducedfromcoconutshell,and byOliveira[12]instudieswithzeolites.Intheseworks,the maxi-mumsulphateloadingsobservedwere55.6mgg−1,4.9mgg−1and 53.8mgg−1,respectively.

Aspredictedbyconstant bin theLangmuirmodel,thevan’t Hoffequation(Eq.(8))[27]confirmedthatsulphatesorptionby AmberlystA21is anexothermicprocess (H=−25.06kJmol−1) related to a decrease in entropy (S=−0.042kJmol−1K−1) of

the system (Fig. 4, Table 3). A study of sulphate sorption

on activated carbon revealed it to be an endothermic process

Table3

Changesofenthalpy,H,Gibbsfreeenergy,Gandentropy,S,relatedtosulphate

adsorptionprocessbyAmberlystA21resin,atpH4andstirringrateof180min−1.

Temperatura(◦C) H(kJmol−1) S(kJmol−1K−1) G(kJmol−1)

34 −12.21

50 −25.06 −0.042 −10.25

0 50 100 150 200 250 0.0

0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0

Time (min)

C

t/C

oC

o= 55

mg(SO

42-) L

-1C

o=80

mg(SO

42-) L

-1C

o=160

mg(SO

42-) L

-1(a)

0 50 100 150 200 250

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0

C

t/C

oTime (min)

H = 6 cm

H = 9 cm

H = 12

cm

(b)

0 50 100 150 200 250

0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0

C

t/C

oQ = 10

mL min

-1Q = 15

mL min

-1Q = 20

mL min

-1Time (min)

(c)

Fig.5.BreakthroughcurvesforsulphatesorptionbyAmberlystA21resin,at

differ-entinletconcentrations(C0)(a),bedheight(H)(b)andflowrate(Q)(c).Experimental

conditions:pH4,28±1◦Cand0.35bedporosity.Fixedconditions:inletsulphate

concentrationof80mgL−1,bedheightof9cmandflowrateof15mLmin−1.

(H=15.4kJmol−1) that occurred with an increase in entropy (S=0.133kJK−1mol−1)[10].

TheHvaluelowerthan40kJmol−1(inabsoluteterms)implied

that physisorption was the main sorption mechanism [6,28],

whereas thenegativeSvalueswere interpretedtoindicate a

reductioninsulphateaccessibilitytotheresincorewithincreasing temperature[27].ItisalsoworthnotingthattheGibbsfreeenergy relatedtosulphatesorptionbyAmberlystA21wasalsomeasured (Eq.(9)),andtheresultsarepresentedinTable3.Such thermody-namicparameters,however,refertotheoverallsorptionprocess, i.e.,theyincludeboththeprotonationofthefunctionalgroupsand sulphateadsorptionsteps.

AnimportantfeaturetobeaddressedinapplyingAmberlystA21 inthetreatmentofsulphate-ladeneffluentsisresinelution[29].As observedinthestudyoftheinfluenceofpHonsulphateadsorption byAmberlystA21,aminefunctionalgroupsarenotprotonatedin

Table4

SulphateelutionofAmberlystA21resin,at30◦

Candstirringrateof180min−1.

Initialsulphateloading

(mg(SO42−)mL(resin)−1)

Dessorption

efficiency(%)

Eluant

10.4 ∼100 SolutionofNaOH

(pH10)

∼100 SolutionofNaOH

(pH12)

alkalineconditions,resultinginlowsulphateloadings.Therefore, elutionwascarriedoutbysettingthepHoftheeluentsolutionto 10and12,whichgaveyieldsapproaching100%(Table4).Similar tothecurrentstudy,Fengetal.[13]observedelutionyieldsfor theionexchangeresinsDuoliteA161,DuoliteA375andAmberlite IRA67between90%and95%whenapplyingCa(OH)2solutions con-taining2%NaOH.Moreover,MoretandRubio[7]observednearly 96%sulphateelutionfromshrimppeelingsfunctionalizedwith ter-tiaryaminegroupsafterincreasingthepHto12.Efficientsulphate desorptionfromcarbonproducedfromcoconutshellandactivated withZnCl2wasalsopromotedinanalkalinemedium(pH11)with 90%efficiency[10].

3.2. Fixed-bedexperiments

Fig.5(a)and (b)presentsthebreakthrough curvesproduced fromsolutionscontainingdifferentsulphate concentrationsand beddepths, respectively,ata flow rateof15mLmin−1.Table5 depictsthemeasuredsorptionparameters.Thecurvesdemonstrate that either increasingthe solution concentration or decreasing thebeddepthresultedinreachingbreakthroughandsaturation pointsmorerapidly;thus,asmallervolumeofsolutionistreated at breakthrough.Theseoutcomes werea resultof thefactthat theadsorption capacity isfinite and wasreachedmore rapidly atlargerinletconcentrationsorlowerbedheights.Irrespectiveof theparameterinvestigated,thesamecapacitiesofapproximately 10mg(SO42−)mL(resin)−1weredetermined.Fig.5(c)andTable5 demonstratethatincreasingtheflowratereducedthetimeneeded toreachthebreakthroughandsaturationpoints.Becauseincreased flowratesimplylesscontacttimebetweentheresinandthe solu-tion,therewasaslightreductioninsorptioncapacitytoavalue around8mgmL(resin)−1,whichisconsistentwiththestudyby Haghshenoetal.[21]ontheresinLewaitK6362.

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200 0.0

0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0

C

t/C

oTime (min)

SO

4Cl

F

-Fig.6.Breakthroughcurvesfortheadsorptionofthemajoranionspresentinthe

metallurgicalindustryeffluenttreatedinafixed-bedofAmberlystA21.

Experimen-talconditions:pH3.2,25±1◦C,bedheightof9cm,0.35bedporosityandflowrate

Table5

Experimentaldataobtainedwithfixedbedexperimentscarriedoutat28±1◦C,pH4,porosityof0.35,varyingthesulphateinletconcentration,bedheightandflowrate.

Varied experimental condition

Breakthrough

volume(mL)

Breakthrough

time(min)

Saturation

volume(mL)

Saturationtime

(min)

Bedcapacityof

adsorption

(mg(SO42−))

Maximumloadingofresin

(qmax)

(mg(SO42−)mL(resin)−1)

Sulphateinletconcentration

(mg(SO42−)L−1)

55 600 40 1500 100 93.8 8.52

80 450 30 1200 80 105.7 9.61

160 150 10 750 50 126.7 11.5

Bedheight

(cm)

6 150 10 1200 80 101.6 12.7

9 300 20 1350 90 111.6 10.1

12 450 30 1650 110 138.7 9.6

Flowrate

(mLmin−1)

10 400 40 1100 110 88.5 8.1

15 450 30 1200 80 95.6 8.7

20 400 20 1200 60 96.8 8.8

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180

0 100 200 300 400 500 600

Su

lpha

te

c

on

cen

tr

a

tio

n

mg

mL

(r

es

in)

-1

Time (min)

Fig.7.Desorptioncurveofthebedloadedbythemetallurgicaleffluentbyusingof

sodiumhydroxide(pH12).Experimentalconditions:25±1◦C,bedheightof9cm,

0.35bedporosityandflowrateof10mLmin−1.

Fig.6 showsthebreakthroughcurveobtainedinthe experi-mentsperformedwithanindustrialeffluent(Table1).Atlowresin loadings,therewerefreetertiaryaminefunctionalgroupsandthus bothchlorideandsulphateionswereadsorbed.Asthesegroups wereoccupied,acompetitionbetweenchlorideandsulphatewas thenobserved.Becausesulphatehasahigheraffinityfortheresin, chlorideovershootingwasobservedduringtheloadingasindicated byCt/Co ratioslargerthan1,forchloride.Therefore,nochloride loadingontheresinwasobservedattheendoftheexperiment. Thatwasconfirmedbythedesorptionexperimentswhoseresults arepresentedinFig.7andrevealednochlorideintheeluate,i.e. onlysulphateanionsweredetected.Furthermore,theindustrial effluentalsocontainedfluorideionsbutthelatterwasnotadsorbed

atanymoment.

Approximately 150min were necessary to saturate the

resinwhosemaximumloadingwas14.27mg(SO42−)mL(resin)−1 whereasapproximately80minwererequiredduringelution.Resin loadingintheexperimentwiththeindustrialeffluentwashigher

thanthoseobtainedinbatchtests(carriedoutatpH4).Itislikely thatthehigherloadingobservedintheexperimentwithareal efflu-entisduetothepHoftheeffluentwhichwas3.2.AccordingtoFig.1, thelowerthepH,thehighertheloadingcapacityoftheresindue toitsfunctionalgroupsprotonation(Eqs.(1)and(2)).

4. Conclusions

Thepresentstudyshowedtheapplicationoftheionexchange resin Amberlyst A21in sulphate sorption for thefirst time. By

a comprehensive investigation of different parameters related

to its sulphate sorption performance, it was possible to

con-cludethattheprocesshaspositivefeatures thatmakeitagood

candidate for use in sulphate removal applications. In acidic

conditions, the process is fast (k=1.67×10−4s−1), exothermic (H=−25.06kJmol−1)andcanbecarriedoutinbothbatchand fixed-bedcolumnswithnodifferenceinthemaximumadsorption capacity(11.6mg(SO42−)mL(resin)−1).Althoughthisadsorption capacityis lowcompared tostrongbaseresins,100%resin elu-tioniseasilyaccomplishedbyincreasingthepHto10and12with sodiumhydroxidesolutions.Theexperimentswithanindustrial effluentindicatedthatfluorideionsdonotinterfereonthesulphate loading.Conversely,althoughchloridewasalsoloaded,itwaslater desorbedasthebedbecamesaturatedwithsulphate,whichhada higheraffinityfortheresin.

Acknowledgements

FinancialsupportfromthefundingagenciesFINEP,FAPEMIG, CNPq,CAPESandValeisgratefullyappreciated.

References

[1]INAP,Treatmentofsulphateinmineeffluentes,in:InternationalNetworkfor

AcidPrevention,2003,p.129.

[2]WHO,in:GuidelinesforDrinking-WaterQuality,Genebra,2008,p.668.

[3]R.J.Bowell,Sulphateandsaltminerals:theproblemoftreatingminewaste,in: MineEnvironmentalMangazine,2000,pp.11–13.

[5]USEPA,in:SulfateinDrinkingWater,U.S.EnvironmentalProtectionAgency,

Washington,DC,1999.

[6]T.D.Reynolds,P.Richards,UnitOperationsandProcessesinEnvironmental Engineering,2nded.,PWSPublishingCompany,Boston,1995.

[7]A.Moret,J.Rubio,Sulphateandmolybdateionsuptakebychitin-basedshrimp shells,Miner.Eng.16(2003)715–722.

[8]D.R.Mulinari,M.L.C.P.daSilva,Adsorptionofsulphateionsbymodificationof sugarcanebagassecellulose,Carbohydr.Polym.74(2008)617–620. [9]W.Cao,Z.Dang,X.-Q.Zhou,X.-Y.Yi,P.-X.Wu,N.-W.Zhu,G.-N.Lu,Removalof

sulphatefromaqueoussolutionusingmodifiedricestraw:preparation, charac-terizationandadsorptionperformance,Carbohydr.Polym.85(2011)571–577. [10]C.Namasivayam,D.Sangeetha,Applicationofcoconutcoirpithfortheremoval

ofsulfateandotheranionsfromwater,Desalination219(2008)1–13. [11]A.M.Silva,R.M.F.Lima,V.A.Leão,Minewatertreatmentwithlimestonefor

sulfateremoval,J.Hazard.Mater.221–222(2012)45–55.

[12]C.R.Oliveira,Adsorc¸ão–remoc¸ãodesulfatoeisopropilxantatoemzeólita

nat-uralfuncionalizada,MSc,UniversidadeFederaldoRioGrandedoSul,Porto

Alegre,2006,107pp.

[13]D.Feng,C.Aldrich,H.Tan,Treatmentofacidminewaterbyuseofheavymetal precipitationandionexchange,Miner.Eng.13(2000)623–642.

[14]D.Guimarães,TratamentodeEfluentesRicosemSulfatoporAdsorc¸ãoem

ResinadeTroca-Iônica,MasterThesis,UniversidadeFederaldeOuroPreto,

OuroPreto,MG,Brasil,2010,170pp.

[15]H.Qiu,L.Lv,B.C.Pan,Q.J.Zhang,W.M.Zhang,Q.X.Zhang,Criticalreviewin adsorptionkineticmodels,J.ZhejiangUniv.Sci.A10(2009)716–724.

[18]Y.S.Ho,G.McKay,Pseudo-secondordermodelforsorptionprocesses,Process Biochem.34(1999)451–465.

[19]J.Weber,J.C.Morris,Kineticsofadsorptiononcarbonsolution,J.Sanit.Eng.89 (1963)31–59.

[20]M.Chabani,A.Amrane,A.Bensmaili,Kineticmodellingoftheadsorptionof nitratesbyionexchangeresin,Chem.Eng.J.125(2006)111–117.

[21]R.Haghsheno,A.Mohebbi,H.Hashemipour,A.Sarrafi,Studyofkineticand fixedbedoperationofremovalofsulfateanionsfromanindustrialwastewater byananionexchangeresin,J.Hazard.Mater.116(2009)961–966.

[24]S.S.Tahir,N.Rauf,ThermodynamicstudiesofNi(II)adsorptionontobentonite fromaqueoussolution,J.Chem.Thermodyn.35(2003)2003–2009. [25]H.Zheng,L.Han,H.Ma,Y.Zheng,H.Zhang,D.Liu,S.Liang,Adsorption

char-acteristicsofammoniumionbyzeolite13X,J.Hazard.Mater.158(2008) 577–584.

[26]B.Kemer,D.Ozdes,A.Gundogdu,V.N.Bulut,C.Duran,M.Soylak,Removalof fluorideionsfromaqueoussolutionbywastemud,J.Hazard.Mater.168(2009) 888–894.

[27]E.L.Schineider,Adsorc¸ãodecompostosfenólicossobrecarvãoativado,93pp., UniversidadeEstadualdoOestedoParaná,Toledo,2008.

[28]G.Bayramoglu,B.Altintas,M.Y.Arica,Adsorptionkineticsandthermodynamic parametersofcationicdyesfromaqueoussolutionsbyusinganewstrong cation-exchangeresin,Chem.Eng.J.152(2009)339–346.