Base of the skull morphology and Class III malocclusion in

patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate

Mariana Maciel Tinano1, Milene Aparecida Torres Saar Martins2, Cristiane Baccin Bendo3, Ênio Mazzieiro4

Objective: The aim of the present study was to determine the morphological differences in the base of the skull of individuals with cleft lip and palate and Class III malocclusion in comparison to control groups with Class I and Class III malocclusion.

Methods: A total of 89 individuals (males and females) aged between 5 and 27 years old (Class I, n = 32; Class III, n = 29; and Class III individuals with unilateral cleft lip and palate, n = 28) attending PUC-MG Dental Center and Cleft Lip/Palate Care Center of Baleia Hospital and PUC-MG (CENTRARE) were selected. Linear and angular measurements of the base of the skull, maxilla and mandible were performed and assessed by a single calibrated examiner by means of cephalometric radio-graphs. Statistical analysis involved ANCOVA and Bonferroni correction. Results: No significant differences with regard to the base of the skull were found between the control group (Class I) and individuals with cleft lip and palate (P > 0.017). The cleft lip/palate group differed from the Class III group only with regard to CI.Sp.Ba (P = 0.015). Individuals with cleft lip and palate had a significantly shorter maxillary length (Co-A) in comparison to the control group (P < 0.001). No significant differ-ences were found in the mandible (Co-Gn) of the control group and individuals with cleft lip and palate (P = 1.000). Conclu-sion: The present findings suggest that there are no significant differences in the base of the skull of individuals Class I or Class III and individuals with cleft lip and palate and Class III malocclusion.

Keywords:Angle Class III malocclusion. Base of the skull. Cleft lip and palate.

How to cite this article: Tinano MM, Martins MATS, Bendo CB, Mazzie-iro E. Base of the skull morphology and Class III malocclusion in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate. Dental Press J Orthod. 2015 Jan-Feb;20(1):79-84. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2176-9451.20.1.079-084.oar

» The authors report no commercial, proprietary or financial interest in the prod-ucts or companies described in this article.

Contact address: Mariana Maciel Tinano E-mail: maritinano@yahoo.com.br 1 PhD resident in Child and Adolescent Health, School of Medicine — Federal

University of Minas Gerais (UFMG).

2 Postdoc resident in Pediatric Dentistry, Federal University of Minas Gerais

(UFMG).

3 Assistant professor, Department of Orthodontics and Pediatric Dentistry,

Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG). 4 PhD in Orthodontics, University of São Paulo (USP).

Submitted: February 21, 2014 - Revised and accepted: May 26, 2014 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2176-9451.20.1.079-084.oar

Objetivo: o objetivo do presente estudo foi determinar diferenças morfológicas da base do crânio de indivíduos portado-res de fissura de lábio e palato e de má oclusão de Classe III, comparado-os com indivíduos controle com má oclusão de Classes I ou III. Métodos: oitenta e nove indivíduos, de ambos os sexos, com idade variando entre 5 e 27 anos, Classe I (n = 32), Classe III não fissurados (n = 29) e Classe III com fissura labiopalatina unilateral (n = 28), oriundos do Centro de Odontologia e Pesquisa da PUC-MG e do Centro de Atendimento de Fissurados do Hospital da Baleia e da PUC-MG (CENTRARE), foram selecionados. Medições lineares e angulares da base do crânio, maxila e mandíbula foram reali-zadas e avaliadas por um único examinador calibrado, por meio de radiografias cefalométricas. Foram utilizados os testes ANCOVA e correção de Bonferroni para a análise estatística dos dados. Resultados: com relação à base do crânio, os resultados não indicaram diferença estatística entre indivíduos controle (Classe I) e os indivíduos com fissuras (p > 0,017). O grupo com fissura foi diferente do grupo Classe III somente em relação à medida CI.Sp.Ba (p = 0,015). O compri-mento maxilar (Co-A) apresentou diferença estatisticamente significativa na comparação entre o grupo controle (Classe I) e o grupo com fissuras (p < 0,001), sendo que os fissurados apresentaram uma maxila menor. Não foram encontradas diferenças na mandíbula (Co-Gn) entre indivíduos do grupo controle (Classe I) e indivíduos fissurados (p = 1,000). Con-clusão: os resultados sugerem que não houve diferença estatisticamente significativa na base do crânio entre indivíduos Classe I e III e indivíduos com fissuras de lábio e palato com má oclusão de Classe III.

INTRODUCTION

Correlations between the development of the base of the skull and maxillofacial components have been

dem-onstrated in facial development studies.1-4 The

morphol-ogy of the base of the skull may be an important factor in the anteroposterior relationship of the maxilla and

man-dible as well as in determining Class III malocclusion.5,6,7

Class III malocclusion results from a combination of morphological abnormalities of the base of the skull, maxilla and mandible as well as in vertical facial

dimen-sions.5,8-11 Morphological variability in the craniofacial

complex of individuals with Class III sagittal relation-ship suggests the inluence of the base of the skull in the development of this type of malocclusion. Individuals with greater lexure of the base of the skull angle reveal a reduction in the horizontal dimension of the middle cranial fossa, with a consequent tendency toward na-somaxilllary retrognathism, a more forward position-ing of the mandible and a prognathic craniofacial

pro-ile.12 Moreover, a lower angle between the ramus of the

mandible and the base of the skull, a smaller and more retrognathic maxilla and a larger and more prominent mandible can lead to Class III malocclusion associated

with Class III facial pattern.11,13

The development of the craniofacial complex in pa-tients with clet lip and palate has been studied in an at-tempt to establish the mechanisms and determinant fac-tors of facial development in such individuals. A number of studies state that the base of the skull is intrinsically diferent in shape and size in patients with clet lip and

palate.14-18 This diference may afect the growth and

po-sitioning of facial structures, with an increased lexure of the base of the skull, thereby favoring the development of a Class III skeletal relationship. Nevertheless, other studies report that individuals with clet lip and palate do not present signiicant diferences in the base of the skull

of which development is normal.19,20,21 Abnormalities in

intermaxillary and interalveolar sagittal relationships in such patients may stem primarily from a reduction in the depth of the maxilla, with no changes in the rotation or

length of the ramus of the mandible.22 Thus, the

antero-posterior deformities oten found in such individuals may actually result from surgical trauma, adaptive changes or a combination of both.

The literature does not reach a consensus regarding base of skull morphology in patients with unilateral clet lip and palate. Additionally, there is considerable lack of

current studies on this subject. For this reason, the aim of the present study was to compare the morphology of the base of the skull in individuals with unilateral clet lip and palate and Class III malocclusion with control individuals with Class I and Class III malocclusion.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Catholic University of Minas Gerais Institutional Review Board (PUC-MG) under protocol CAAE - 0012.0.213.000-07.

Sample

The sample comprised 89 lateral cephalograms col-lected from the iles of PUC-MG Dental Research Center and the Clet Lip/Palate Care Center of Baleia Hospital and PUC-MG (CENTRARE). All cephalo-grams were taken from male and female patients at orth-odontic treatment onset. Patients were aged between 5 and 27 years old (mean = 12.9; median = 12.0).

The sample was divided into three study groups:

1 - Control group comprising 32 cephalograms of

Class I individuals with no history of orthodontic treatment; 2 - Group 2 comprising 29 cephalograms of Class III individuals with no history of orthodontic treatment; and 3 - Group 3 comprising 28 cephalograms of nonsyndromic, unilateral clet lip/palate Class III in-dividuals having undergone correction for clet lip/pal-ate at an early age (lip surgery at a mean age of 6 months, and palate surgery at a mean age of 18 months).

Measurement methods

Cephalometric tracings were performed manually on acetate paper and based on patients’ cephalograms. All tracings were performed by a single calibrated examiner. Intraexaminer agreement was assessed by paired Student’s t-test. Linear and angular measure-ments were performed on two separate occasions with a 10-day interval in between. The p-value generated by the paired Student’s t-test was 0.446 for linear measure-ments and 0.392 for angular measuremeasure-ments, thereby demonstrating no signiicant diferences between mea-surements taken on the two diferent occasions.

The cephalometric landmarks used in the present

study were as described by Jacobson:23 sella (S),

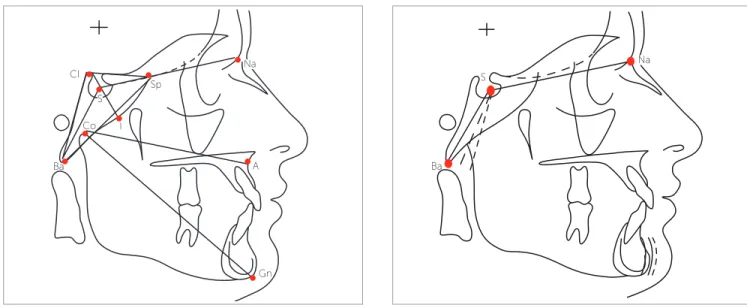

Figure 1 - Cephalometric landmarks, linear and angular measurements. Figure 2 - Ba.S.N angular measurements demonstrating flexure of the base of the skull angle.

and Cl-I) and angular (Ba.S.N, Ba.Cl.Sp, Cl.Ba.Sp and Cl.Sp.Ba) measurements were taken as shown in Figure 1. The height of the base of the skull (Cl-I) was measured by the distance of a straight line from Cl and S landmarks and a point intercepting the greater wing of the sphenoid bone at a point established as point I (I) (Fig 1).

Data analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows, version 19.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis. Initially, the three groups were analyzed with regard to age. As Shapiro-Wilk test determined that this variable was not normally distributed, Kruskal-Wallis test was used and revealed signiicant diferences among the three groups with regard to age(P = 0.032).

Conversely, Shapiro-Wilk test determined that linear and angular measurements were normally distributed, for this reason, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used for statistical analysis of data. Analysis of covariance is jus-tiied by the potential interference of age in the mean lin-ear and angular measurements. In cases of signiicant dif-ferences among groups, Bonferroni correction was used to identify in which groups the diference was found. To prevent errors arising from multiple comparisons, the signiicance level (0.05) was divided by the number of

comparisons;24 thus, p-values less than 0.017 were

con-sidered statistically signiicant (0.05 divided by 3).

RESULTS

Table 1 displays the angular measurements in the three groups. The clet lip/palate group had intermediate mea-surements of the base of the skull that ranged between the control and Class III groups. No signiicant diferences were found between the clet lip/palate group and the control group (Class I). The clet lip/palate group signiicantly dif-fered from the Class III group only with regard to CI.Sp.Ba (P = 0.015). Signiicant diferences in Ba.S.N, Ba.CI.Sp and CI.Sp.Ba were found between the control (Class I) and Class III groups. The lowest Ba.S.N was found in the Class III group, thereby indicating greater lexure of the base of the skull angle in comparison to the other groups (Fig 2).

Table 2 displays the linear measurements in the three groups. Mean Co-A (maxilla) was greater in the control group (Class I) (90.8 mm) and lower in the clet lip/pal-ate group (85.1 mm). This diference was statistically sig-niicant (P < 0.001). Considering a p-value lower than 0.017 as statistically signiicant (as determined by Bon-ferroni correction), no signiicant diference was found between the Class III group and the clet lip/palate group (P = 0.032). Mean length of the mandible (Co-Gn) was greater in the clet lip/palate group (116.3 mm) in com-parison to the other groups. However, this diference was not statistically signiicant. While no signiicant difer-ences were found with regard to angular measurements, the linear measurements of the base of the skull were lower, except for S-N and Ba-Sp.

CI

S

S

Co I

Sp

Ba Ba

Gn A

Table 1 - Mean angular measurements in different groups.

Table 2 - Mean linear measurements in different groups.

*Analysis of covariance adjusted for age. SD= standard deviation; G1= group 1; G2= group 2; G3= group 3. Bonferroni correction= P < 0.017; p-values in bold significant at 0.017.

*Analysis of covariance adjusted for age. SD= standard deviation; G1= group 1; G2= group 2; G3= group 3. Bonferroni correction = P < 0.017; p-value in bold significant at 0.017.

Groups

P-value*

Variable Control (G1) Class III (G2) Cleft (G3) Comparison between groups

Mean ± SD Mean ± SD Mean ± SD G1 x G2 G1 x G3 G2 x G3

Ba.S.N 130.1 ± 5.0 125.6 ± 4.5 127.9 ± 5.0 0.002 0.001 0.275 0.192

Ba.Cl.Sp 114.7 ± 6.9 108.5 ± 6.9 113.2 ± 5.2 0.002 0.002 1.000 0.037

Cl.Ba.Sp 23.4 ± 2.6 25.2 ± 2.8 24.3 ± 2.7 0.080 - -

-Cl.Sp.Ba 42.1 ± 5.3 46.3 ± 5.5 42.5 ± 3.6 0.003 0.004 1.000 0.015

Groups

Variable Control (G1) Class III (G2) Cleft (G3) P-value* Comparison among groups

Mean ± SD Mean ± SD Mean ± SD G1 x G2 G1 x G3 G2 x G3

S-N 70.4 ± 5.1 68.5 ± 4.2 71.4 ± 4.9 0.591 _ _ _

S-Ba 46.5 ± 3.0 45.9 ± 3.0 45.3 ± 4.0 0.049 1.000 0.113 0.082

Co-A 90.8 ± 7.8 86.1 ± 6.0 85.1 ± 7.0 < 0.001 0.208 < 0.001 0.032

Co-Gn 114.7 ± 9.7 114.6 ± 10.9 116.3 ± 9.7 0.029 0.050 1.000 0.069

Ba-Cl 49.4 ± 3.6 49.2 ± 3.2 48.1 ± 4.5 0.051 - -

-Sp-Cl 29.3 ± 2.5 29.5 ± 2.7 29.1 ± 2.9 0.726 - -

-Ba-Sp 66.8 ± 3.5 64.3 ± 3.6 64.9 ± 5.5 0.072 - -

-Cl-I 25.1 ± 2.6 25.9 ± 2.4 24.6 ± 3.2 0.028 0.191 1.000 0.027

DISCUSSION

In the present study, no signiicant diferences were found with regard to the linear measurements of the base of the skull (S-Ba, Ba-Cl, Sp-Cl, Ba-Sp and Cl-l) (P > 0.017), even though they were lower in the clet lip/ palate group in comparison to control (Class I). These

results are in agreement with others studies17,20,25

report-ing that shorter measurements may be attributed to the small body children with clet lip/palate normally have.

No signiicant diferences were found for S-N among groups; however, mean S-N was greater in the clet lip/ palate group in comparison to the other groups. This is

in disagreement with others studies15,16,26,27,28 reporting

lower S-N in children with clet lip and palate, thereby suggesting a relative diference in the craniofacial mor-phology of such individuals. Nevertheless, the majority of the aforementioned studies included individuals with diferent types and degrees of clet lip and palate, which may explain the divergent indings.

Signiicant diference was found in Co-A between the control (Class I) and the clet lip/palate group (P < 0.001), as the former had the greatest whereas the latter had the shortest measurement among the three groups, thereby suggesting a deiciency in the efective length of the maxilla in this group. This result is in

agreement with other studies29-33 reporting the efect

of surgical procedures on the anteroposterior growth and development of the maxilla in children with clet lip and palate due to the formation of ibrous scar tissue at the surgery site. However, it is not yet clear whether maxillary retrognathism may also be related to intrin-sic development deiciencies in such individuals. In

some studies,25,34,35 the maxilla of individuals with clet

No statistically signiicant diference was found with regard to the linear measurement of mandibular length (Co-Gn) (P > 0.017), which is in agreement with other

studies21,25,26,36,37 reporting that the mandible of

individ-uals with clet lip and palate is equal in length to that of individuals without this condition. Likewise, no signii-cant diferences were found between the control and the Class III malocclusion group, which is in disagreement

with other studies9,10 concluding that mandibular length

progressively increases with age of Class III individuals. No signiicant diference was found in the base of the skull angle (Ba.S.N), particularly between control and clet lip/palate group (P = 0.275). This is in agreement

with previous studies16,19,20,25,27 reporting that the

maloc-clusion found in this group is much more the result of maxillary retrognathism caused by surgical trauma than the presence of a more lexed base of the skull, thereby determining the emergence of mandibular prognathism. However, signiicant diferences were found between the control and the Class III malocclusion group, with

a smaller angle in the latter group (125.6o). Other

stud-ies8,10,38,39 also report that Class III individuals have

mor-phological abnormalities in the craniofacial complex, with a reduction in the angle formed by the anterior and posterior segments of the base of the skull. The posterior base of the skull (S-Ba) exerts signiicant inluence in the emergence of mandibular prognathism. This mandibular rotation caused by reduction in the angle may indicate an increase in the length of the linear measurement Cl-I due to the base of the skull being represented by a triangle in

this study. Thus, the greater height of the base of the skull in Class III individuals may be the consequence of greater lexure of this structure.

No signiicant diferences were found between the control and the clet lip/palate group regarding the angular measurements of the base of the skull (Ba. Cl.Sp, Cl.Ba.Sp and Cl.Sp.Ba), thereby conirming absence of morphological diferences between the two groups. However, signiicant diferences in Ba.Cl.Sp and Cl.Sp.Ba were found between the control and the Class III malocclusion group, thereby demonstrating morphological diferences in the craniofacial complex of these two groups.

Based on the results of this study it is reasonable to assert that, the base of the skull in individuals with uni-lateral clet lip and palate does not difer signiicantly from that of individuals with Class I malocclusion; its development is, therefore, normal. In contrast, cranio-facial morphology in individuals with Class III maloc-clusion difers signiicantly from that of individuals with Class I malocclusion, thereby suggesting that structural alterations in this morphology may inluence the emer-gence of Class III malocclusion.

CONCLUSION

1. Bjork, A. Base of the skull. Am J Orthod.1955;41:198-225.

2. Hopkins GB, Houston WJ, James GA. The base of the skull as an aetiological factor in malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 1968;38(3):250-5.

3. Enlow D, Kuroda T, Lewis A. The morphological and morphogenetic basis for craniofacial form and pattern. Angle Orthod.1971;41:161-88.

4. Enlow D, McNamara Jr JA. The neurocranial basis for facial form and pattern. Angle Orthod. 1973;43:256-70.

5. Sanborn RT. Diferences between the facial skeletal patterns of class III malocclusion and normal occlusion. Angle Orthod. 1955;25(4):208-222. 6. Guyer EC, Ellis EE 3rd, McNamara JA Jr, Behrents RG. Components of class III

malocclusion in juveniles and adolescents. Angle Orthod. 1986;56(1):7-30. 7. Chang HP, Liu PH, Tseng YC, Yang YH, Pan CY, Chou ST. Morphometric analysis

of the base of the skull in Asians. Odontology. 2014;102(1):81-8.

8. Singh GD, McNamara Jr JA, Lozanof S. Finite element analysis of base of the skull in subjects with class III malocclusion. Br J Orthod. 1997;24(2):103-12. 9. Miyajima K, McNamara JA Jr, Sana M, Murata S. An estimation of craniofacial

growth in untreated class III female with anterior crossbite. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;112(4):425-34.

10. Mouakeh M. Cephalometric evaluation of craniofacial pattern of Syrian children with Class III malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;119(6):640-9. 11. Chang HP, Hsieh SH, Tseng YC, Chou TM. Cranial-base morphology in children

with class III malocclusion. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21(4):159-65. 12. Lavelle CLB. A study of craniofacial form. Angle Orthod. 1979;49:65-72. 13. Battagel JM. The aetiological factors in Class III malocclusion. Eur J Orthod.

1993;15(5):347-70.

14. Moss ML. Malformations of skull base associated with cleft palate deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg (1946). 1956;17(3):226-34.

15. Dalh E. Craniofacial morphology in congenital clefts of lip and palate. Acta Odontol Scand.1970;28:83-100.

16. Hoswell BB, Gallup BV. Base of the skull morphology in cleft lip and palate: A cephalometric study from 7 to 18 years of age. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992;50:681-5.

17. Harris EF. Size and form of base of the skull in isolated cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1993;30(2):170-4.

18. Cortés J, Granic X. Characteristic craniofacial features in a group of unilateral cleft lip and palate patients in Chile. Rev Stomatol Chir Maxillofac. 2006;107(5):347-53.

19. Brader AC. A cephalometric appraisal of morphological variations in base of the skull and associated pharyngeal structures. Angle Orthod. 1957;27:179-95. 20. Ross RB. Base of the skull in children with cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate J.

1965;2:157-66.

21. Chierici G, Harvold E, Vargervik K. Morphogenetic experiments in cleft palate: mandibular response. Cleft Palate J. 1973;10:47-56.

22. Velemínská J. Analysis of intracranial relations in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate using cluster and factor analysis. Acta Chir Plast. 2000;42(1):27-36.

REFERENCES

23. Jacobson A. Radiographic Cephalometry. Chicago: Quintessence; 1995. 24. Nahler G. Dictionary of Pharmaceutical Medicine. New York: Springer-Verlag /

Wien; 2009.

25. Bishara SE, Iversen WW. Cephalometric comparisons on the base of the skull and face in ndividuals with isolated clefts of the palate. Cleft Palate J. 1974;11:162-75.

26. Krogman WM, Mazaheri M, Harding RL, Ishiguro K, Bariana G, Meier J, et al. A longitudinal study of craniofacial growth pattern in children with clefts as compared to normal, birth to six years. Cleft Palate J. 1975;12(00):59-84. 27. Sandham A, Cheng L. Base of the skull and cleft lip and palate. Angle Orthod.

1988;58(2):163-8.

28. Trotman CA, Collett AR, McNamara JA Jr, Cohen SR. Analyses of craniofacial and dental morphology in monozygotic twins discordant for cleft lip and unilateral cleft lip and palate. Angle Orthod. 1993; 63:135-40.

29. Mestre JC, De Jesus J, Subtelny JD. Unoperated oral clefts at maturation. Angle Orthod. 1960;30:78-85.

30. Huang CS, Wang WI, Liou EJ, Chen YR, Chen PK, Noordhof MS. Efects of cheiloplasty on maxillary dental arch development in infants with unilateral complete cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2002;39:513-6. 31. Singh GD, Rivera-Robles J, de Jesus-Vinas J. Longitudinal craniofacial growth

patterns in patients with orofacial clefts: geometric morphometrics. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004;41:136-43.

32. Liao YF, Mars M. Long-term efects of lip repair on dentofacial morphology in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2005;42:526-32.

33. Corbo M, Dujardin T, de Maertelaer V, Malevez C, Glineur R. Dentocraniofacial morphology of 21 patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate: a cephalometric study. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2005;42(6):618-24.

34. Hagerty RF, Hill MJ. Facial growth and dentition in the unoperated cleft palate. Fissurados. J Dent Res. 1963;42:412-21.

35. Blaine HL. Diferential analysis of palate anomalies. J Dent Res. 1969;48(6):1042-8.

36. Capelozza Filho L, Normando AD, Silva Filho OG. Isolated inluences of lip and palate surgery on facial growth: Comparison of operated and inoperated male adults with UCLP. Cleft Palate Craniofac J.1996;33:51-6.

37. Silva Filho OG, Calvano F, Assunção AG, Cavassan AO. Craniofacial morphology in children with complete unilateral cleft lip and palate: a comparison of two surgical protocols. Angle Orthod. 2001;71(4):274-84.

38. Tanabe Y, Taguchi Y, Noda T. Relationship between base of the skull structure and maxillofacial components in children aged 3-5 years. Eur J Orthod. 2002;24:175-81.