Journal

of

Coloproctology

w w w . j c o l . o r g . b r

Original

article

Quality

of

life

and

self-esteem

of

patients

with

intestinal

stoma

Geraldo

Magela

Salomé

∗,

Sergio

Aguinaldo

de

Almeida,

Maiko

Moura

Silveira

UniversidadedoValedoSapucaí(UNIVÁS),PousoAlegre,MG,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received23February2014 Accepted15May2014

Availableonline22October2014

Keywords:

Ostomy Qualityoflife Bodyimage Self-concept Self-esteem

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Theaimofthisstudywastoinvestigatethequalityoflifeandself-esteeminpatientswith intestinalstoma.Thisisaclinical,primary,descriptive,analyticalstudy,conductedatthe OstomizedPeople’sPoleofPousoAlegre,afterapprovalbytheEthicsCommitteeofthe FaculdadedeCiênciasdaSaúdeDr.JoseAntonioGarciaCoutinhounderopinionNo.23,227. Threeinstruments–aquestionnaireondemographicsandstoma,RosenbergSelf-Esteem Scale/UNIFESP-EPMandFlanaganQualityofLifeScale–wereusedinthedatacollection. Thefollowingtestswereusedforstatisticalanalysis:chi-squaredandKruskal–Wallistests andSpearmancorrelation.Forallstatisticaltests,thelevelofsignificanceof5%(p<0.05) wasconsidered.Mostparticipantswereolderthan60years,ofmalegenderandattended supportgroups.Twenty-one(30%)ofrespondentswereilliterate.Neoplasiawasthemost frequentofthecausesthatledpatientstoreceiveanostomy;permanentcolostomywas thetypeofostomyused.Individualswerenotsubmittedtostomademarcationanddidnot makeirrigation.Regardingthetypeofcomplication,34(48.60%)haddermatitis;14(20%) showedretraction.

ThemeanofRosenbergSelf-EsteemScale/UNIFESP-EPMwas10.81andthemeanof Flana-ganQualityofLifeScalewas26.16.Itwasconcludedthatindividualswithintestinalstoma participatinginthesurveyshowedimpairedself-esteem/qualityoflife.

©2014SociedadeBrasileiradeColoproctologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.All rightsreserved.

Qualidade

de

vida

e

autoestima

em

pacientes

com

estoma

intestinal

Palavras-chave:

Estomia

Qualidadedevida Imagemcorporal Autoimagem Autoestima

r

e

s

u

m

o

Oobjetivodeste estudofoiinvestigaraqualidadede vidaeaautoestimaempacientes comestomaintestinal.Trata-sedeumestudoclínico,primário,descritivoeanalítico.Este estudofoirealizadonoPólodosostomizadosdePousoAlegre,apósaprovac¸ãopeloComitê deÉticaemPesquisadaFaculdadedeCiênciasdaSaúde“Dr.JoséAntônioGarciaCoutinho”, soboparecer no23.277.Foramutilizadostrêsinstrumentosparaa coletade dadosda pesquisa:questionáriosobreosdadosdemográficoseestoma,EscaladeAutoestimade

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:geraldoreiki@hotmail.com,gsalome@infinitetrans.com(G.M.Salomé).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcol.2014.05.009

Rosenberg/UNIFESP–EPMeEscaladeQualidadedeVidadeFlanagan.Foramutilizadosparaa análiseestatísticaosseguintestestes:Qui-quadradoeKruskal-Wallisecorrelac¸ãode Spear-man.Paratodosostestesestatísticos,foiconsideradooníveldesignificânciade5%(p<0,05). Amaioriadosparticipantestinhamaisde60anos,eramdogêneromasculinoe partici-pavamdegrupodeapoio.Vinteeum(30%)dosparticipantesdapesquisaeramanalfabetos. Neoplasiafoiacausamaisfrequenteparaaaquisic¸ãodaostomia;otipodeostomiafoi colostomiapermanente.Osindivíduosnãoforamsubmetidosàdemarcac¸ãodoestomae nemrealizaramirrigac¸ão.Comrelac¸ãoaotipodecomplicac¸ão,34(48,60%)apresentavam dermatite;14(20%)retrac¸ão.AmédiadaEscaladeAutoestimadeRosenberg/UNIFESP–EPM foi10,81eamédiadaEscaladeQualidadedeVidadeFlanagan(EQVF)foi26,16. Concluiu-sequeosindivíduoscomestomaintestinalqueparticiparamdapesquisaapresentavam autoestimaequalidadedevidaprejudicadas.

©2014SociedadeBrasileiradeColoproctologia.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda. Todososdireitosreservados.

Introduction

Astoma isan artificial communication betweenorgans or visceraandtheexternalenvironment,forfeeding,drainage and elimination. The making of an ostomy is a medical-surgicalprocedure.Withrespecttotheoriginofthedisease, theostomymaybetemporaryorpermanent.1

Whenreceivingastoma,theindividualbeginsto evacu-atethroughtheartificialcommunicationinstalledinhis/her abdomen.Atfirst,manypatientswouldratherdiethanlive withthestoma.Overthedays,theystarttorealizethat hav-inganostomymeansgainingtheopportunityforanewlife. Inthissense,itisnoticedthat,afteranostomy,individuals thustreatedexperiencemomentsofemotionalor psycholog-icalchangethat,byaffectingthequalityoflife,self-esteem, bodyimageandeventheirsexuality,cangenerateanxietyand evendepression.

Weobserve thelossofsocialstatusduetothe isolation imposedbytheostomizedindividualhim(her)selfandbythe society,which canrejectthosewho are consideredoutside theso-callednormalpatterns,thatis,thosewhodonothave abodythatfitsthecurrentbeautyandbiomedicalfunctioning parameters.2

Livingwithastomaoftencausesfeelingsoffear,anguish andinsecurity;thesepeoplebelievethattheyarenotableto returntotheiractivitiesoflifeafterhospitalization.Itmust beemphasizedthattheprocessofrehabilitationofostomized peoplebeginspreoperativelyandcontinueswiththeirreturn home,whenanewphasestarts,markedbyprofound biologi-cal,psychosocialandeconomicchanges,andwhitanewbattle whichoughtbefoughtbytheostomizedpersontocopewith, andsurviveto,thenewconditions.3

Qualityoflife(QOL)istheindividual’sperceptionofhis/her healthstatusinrelationtosocial,physical,psychological, eco-nomicandspiritualaspects.4,5

TheWorldHealth Organization(WHO)defines QOL cov-eringfivedimensions:physicalhealth,psychologicalhealth, levelofindependence,socialrelationshipsandenvironment.6

Thus, the quality of lifeand well-being encompass the observationsneededtotheresearchonostomizedpatients,

referring to the person’s physical health, level of inde-pendence,socialrelationships,psychologicalstate,personal beliefsandrelationshipwithkeyaspectsoftheenvironment, whichmaycausechangesinself-esteemandself-image, trigg-eringanxietyanddepression.7–9

The assessment of self-esteem in ostomized people is becoming increasingly important and necessary, because whensubjectedtothissurgery,thesepeoplestartlivinga dif-ferentexperience,wheretheirstandardoflivingandrhythm of lifebegin tochange. Their desires and valuesare often notfulfillednorrespected;theyfeelrejected,seeking seclu-sionbecauseoftheodorandeliminationoffecesthroughthe abdomen.

Notwithstandingtherecognitionoftheimportanceof self-esteemto socialand individual well-beingin thescientific literature, in Brazil there are few studies on the subject, especiallypopulation-basedones.Thus,thisstudyaimedto investigatethequalityoflifeandself-esteeminpatientswith intestinalstoma.

Methods

Thisisaclinical,primary,descriptive,analytical,prospective study.

This study was conducted at the Ostomized People’s Pole at Pouso Alegre. Data were collected in the period between December 2012 and May 2013, after approval by the Research Ethics Committee from the Universidade do Vale doSapucaí under OpinionNo. 23,277.The samplewas selected in a non-probabilistic way and by convenience. Data collection was conducted by the researchers them-selves;allpatientssignedafreeandinformedconsentform. Inclusion criteria were: age≥ 18 years and be user of an

intestinalstoma.Exclusioncriteriawere:patientswith syn-dromesofdementiaand/orotherconditionsthatprevented them from understanding and answering tothe question-naires.

Scale/UNIFESP-EPM;andthethirdwasFlanaganQualityofLife Scale.

TheRosenbergscaleisaninstrumentusedinseveral stud-iesonself-esteem.10-12Itisanunidimensionalscaletranslated

andadaptedinBrazilbyDinietal.13tobeusedintheirstudy,

havingbeenappliedtoapopulationofpatientswho under-wentplasticsurgery.11–13TheRosenbergscaleisaLikert-type

4-pointscale (1=Ifully agree 2=I agree,3=I disagree, 4=I stronglydisagree),containing10items.Ofthistotal,5items evaluatethe individual’spositivefeelingsaboutthemselves (Ingeneral,Iamsatisfiedwithmyself;IfeelIhavesomegood qualities;Iamabletodothingsaswellasmostother peo-ple,providedtheyaretaughttome;IfeelthatIamapersonof worth,atleastonalevelequaltootherpeople;Itakeapositive viewofmyself)and5assessnegativefeelings(AttimesIthink Iamnogoodatall;Idon’tfeelsatisfactioninthethingsthat Ihavedone;IfeelthatIhavenotmuchtobeproudof; some-timesIreallyfeelmyselfuseless,incapableofdoingthings;I wishIcouldhavemorerespectformyself;AlmostalwaysI’m inclinedtothinkI’maloser).Toscoretheresponses,thefive itemsthatexpresspositivefeelingshavetheirvaluesinverted, which,addedtotheotherfive,adduptoasinglevalueforthe scale.Thisscaleconsistsoftenstatementswithfour possi-bleoptionsforresponse.Eachalternativehasavalueranging fromzerotothree.Thus,itpresentsafinalscoreofzeroto30, wherezeroisthebestvalueforself-esteemand30theworst one.

TheFQLS14conceptualizesthequalityoflifebasedonfive

dimensions: physicaland material well-being,relationship withothers,social,communityandcivicactivities,personal developmentandfulfillment,andrecreation.These dimen-sionsare measuredby15items,wherethe respondenthas sevenresponseoptionsrangingfrom“verydissatisfied”(score 1)to“verysatisfied”(score7).105pointsismaximumscore achieved in the assessment of quality of life proposed by Flanagan,14with15pointsbeingtheminimumscore,

reflect-ingalowqualityoflife.Itisworthnotingthatthescale is self-administered; however, some older people involved in thisstudyreceivedhelpfromresearchersintheiranswersto theinstrument,becauseofphysicallimitationssuchashand tremor,decreasedvisualandhearingacuityandlow educa-tionallevel.

The FQLS was developed for the United States and has not been validated for the Brazilian culture; How-ever, Hashimoto et al. held its translation into Portuguese and applied FQLS for ostomized patients.15,16 In 1998,

Gonc¸alves et al. applied the scale in a relatively large and heterogeneous random sample and found high reli-ability for this instrument. Then, these authors used the same scale in astudy involving elderly people,15,16

verify-ing a good level of reliability – a factor that contributed to the decision to use this instrument in the present study.

Inthestatisticalanalysis,thefollowingtestswereused:the chi-squaredtestondemographicvariablesandonthe“related toostomy”variable,todetermineifthedistributionwas pro-portional,thatis,ifthesamenumberofsubjectswasallocated toeachvariablecategory.Kruskal–WallistestandSpearman correlationwerealsoused.Forallstatisticaltests,significance levelsof5%(p<0.05)wereconsidered.

Results

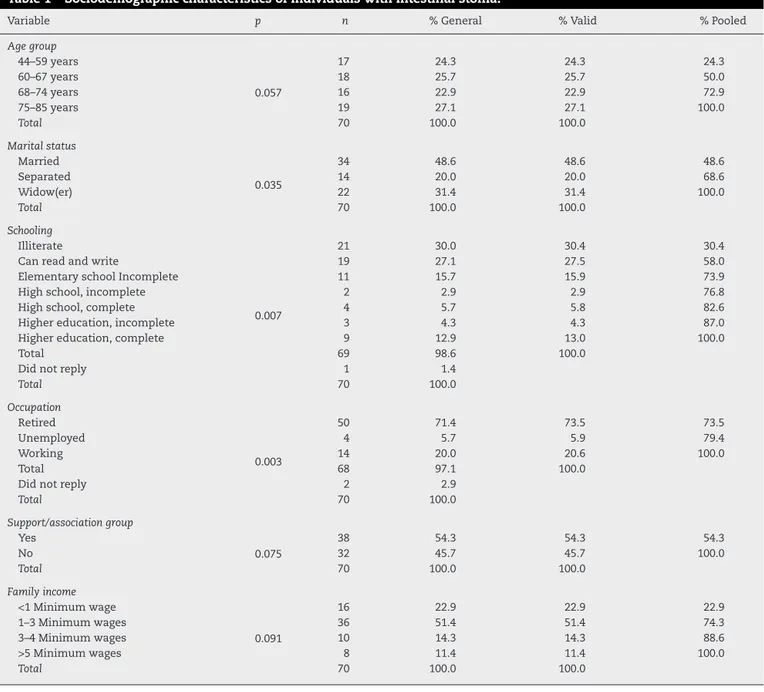

In Table 1, it can be verified that the majority of par-ticipants were above 60 years old, male gender, retired, earned1–3minimumwagespermonthandattendedsupport groups.Twenty-one(30%)ofrespondentswereilliterateand 19(25.10%)couldreadandwrite.

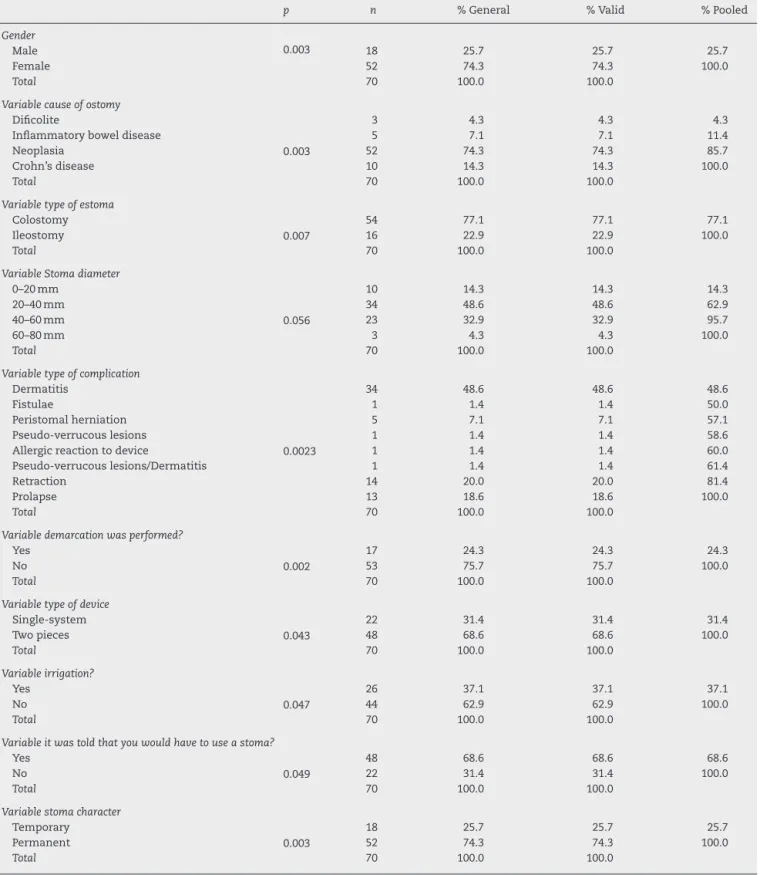

Table2showsthatneoplasiawasthemostfrequentcause for ostomy;permanent colostomy was the typeofostomy used. Most of the subjects were not told that they would receiveastoma.Inaddition,allsubjectswerenotsubmitted tostomademarcationanddidnotmakeirrigation.Regarding thetypeofcomplication,34(48.60%)haddermatitis;14(20%), retractionand13(18.60%),prolapse.Withrespecttothe diam-eter ofthe stoma, 34 (48.60%) measured 20–40mm and 23 (32.90%),40–60mm.

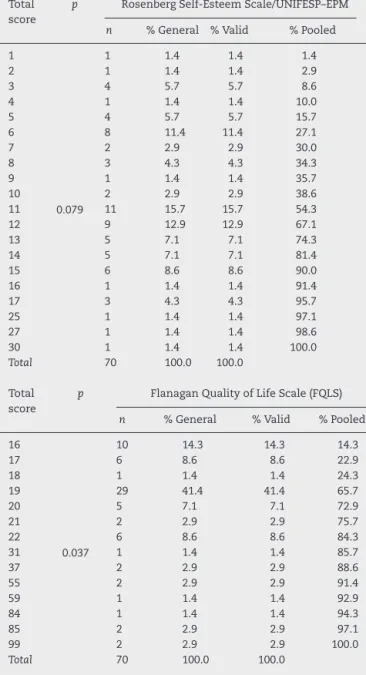

FromTable3,theparticipants’responsesrevealthatthe meanscoreofRosenbergSelf-EsteemScale/UNIFESP-EPMwas 10.81andthe meanscoreofFQLS was26.16,meaningthat theseostomizedpatientshadnegativefeelingsrelatedto self-esteemandshowedadecreasedqualityoflife.

AccordingtoTable4,itwasobservedthatmostof partic-ipantsgotscoresbetween1and15pointsintheSelf-Esteem Scale,andbetween16and22pointsinFQLS,revealingthat thesepatientsshowedqualityoflifeandself-esteemchanges.

Table5showsthattheparticipants’responsesreached60 points(85.70%) forthequestion aboutindependence(being able to do things for yourself) and 62 points (88, 61%) for questions aboutthejob orworkathomeandparticipation inrecreationalandsportsactivities.Suchvaluescharacterize changesintheseaspects.

AccordingtoTable6, amean of1.41–2.0forall 16items was obtained. Thesefindings reflecta lowdegree of satis-faction,thatis,theostomizedindividualsinthisstudywere dissatisfiedwiththeirlives.

Discussion

With regard to sociodemographic characteristics ofour 70 patients with intestinal stoma, most were elderly, over 60 years, were male, retired, earned 1–3 minimumwages per month and attended support groups. Twenty-one patients (30%) were illiterate and 19 (25.10%) could read and write, which is in line with other studies on intestinal stoma users.15–20

Thedatarelatingtostomaindicatedthat,formost partic-ipants,neoplasia wasthecausethatledtostomacreation; andpermanentostomywasthetypeofostomyused.Mostof thesubjectswerenottoldthattheywouldreceivethestoma. Also,theywerenotsubmittedtostomademarcationnorto irrigation.Regardingthetypeofcomplication,34(48.60%)had dermatitis;14(20%)retraction;and13(18.60%),prolapse.As thediameterofthestoma,34(48.60%)measured20–40mm and23(32.90%),40–60mm.Thesefindingsagreewithseveral publishedstudies.15,19–25

Table1–Sociodemographiccharacteristicsofindividualswithintestinalstoma.

Variable p n %General %Valid %Pooled

Agegroup

44–59years

0.057

17 24.3 24.3 24.3

60–67years 18 25.7 25.7 50.0

68–74years 16 22.9 22.9 72.9

75–85years 19 27.1 27.1 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Maritalstatus

Married

0.035

34 48.6 48.6 48.6

Separated 14 20.0 20.0 68.6

Widow(er) 22 31.4 31.4 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Schooling

Illiterate

0.007

21 30.0 30.4 30.4

Canreadandwrite 19 27.1 27.5 58.0

ElementaryschoolIncomplete 11 15.7 15.9 73.9

Highschool,incomplete 2 2.9 2.9 76.8

Highschool,complete 4 5.7 5.8 82.6

Highereducation,incomplete 3 4.3 4.3 87.0

Highereducation,complete 9 12.9 13.0 100.0

Total 69 98.6 100.0

Didnotreply 1 1.4

Total 70 100.0

Occupation

Retired

0.003

50 71.4 73.5 73.5

Unemployed 4 5.7 5.9 79.4

Working 14 20.0 20.6 100.0

Total 68 97.1 100.0

Didnotreply 2 2.9

Total 70 100.0

Support/associationgroup

Yes

0.075

38 54.3 54.3 54.3

No 32 45.7 45.7 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Familyincome

<1Minimumwage

0.091

16 22.9 22.9 22.9

1–3Minimumwages 36 51.4 51.4 74.3

3–4Minimumwages 10 14.3 14.3 88.6

>5Minimumwages 8 11.4 11.4 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

degenerative(andnotdegenerative)chronicdiseases.Often theseconditionsmay implytheuseofanostomy;andthis requiresprofessionals knowledgeableofinnovative techno-logicalresourcesandinapositiontopromoteautonomyfor self-careanddailyactivitiesfortheirpatients,withtheaimto provideabetterqualityoflifeandwell-being.26

When apatientreceives astoma, he/shebeginstoface manychangesinhis/herdailylivethatoccurnotonlyonthe physiologicallevel,butalsoonpsychological,emotionaland sociallevels.Thishasitsconsequences:suffering,pain, dete-rioration,uncertaintyaboutthefutureandfearofrejection.27

Theadaptationprocessoccurs withtheadjustmentofa lifetimeinanewcontext,inwhichimportantfactors often mustbeabandoned,replacedordiminished.Therefore,this isanindividualprocessthattakesplaceovertime,involvinga numberofaspectsrangingfromtheassistancegiven,tohow theostomizedpersonengagesinself-care.28

Inadditiontothepsychological,emotionalandsocial prob-lems already reported earlier,ostomized people face other

setbacks,suchastheexposuretoarangeofsocialconstraints, thepossibilityofoutgassingandexcrementleakageduetothe lackofvoluntarycontrolandalsobyflawsinthesafetyand qualityofthecollectionbag,besidesothercomplications.All inall,thistriggersthefearofpublicexposure.Typically,such problemscanbeunderstoodfromthephysical,psychological, socialandspiritualdimensions.29

Inthisstudy,consideringFQLS,thetotalscorewasbetween 16and26pointsandthemeanwas26.16,meaningthatthese patientsdemonstratedadecreaseintheirqualityoflife.

Aftersurgeryforthecreationofastoma,thepatient expe-riencesmanynegativefeelingsresultingfromphysiological, psycho-emotionalandsocio-culturalchangesthatpermeate his/herlife,provoking,inagreaterorlesserextent,effectsthat mayimpactonitsqualityoflife.

Table2–Intestinalstomacharacteristics.

p n %General %Valid %Pooled

Gender

Male 0.003 18 25.7 25.7 25.7

Female 52 74.3 74.3 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Variablecauseofostomy

Dificolite

0.003

3 4.3 4.3 4.3

Inflammatoryboweldisease 5 7.1 7.1 11.4

Neoplasia 52 74.3 74.3 85.7

Crohn’sdisease 10 14.3 14.3 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Variabletypeofestoma

Colostomy

0.007

54 77.1 77.1 77.1

Ileostomy 16 22.9 22.9 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

VariableStomadiameter

0–20mm

0.056

10 14.3 14.3 14.3

20–40mm 34 48.6 48.6 62.9

40–60mm 23 32.9 32.9 95.7

60–80mm 3 4.3 4.3 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Variabletypeofcomplication

Dermatitis

0.0023

34 48.6 48.6 48.6

Fistulae 1 1.4 1.4 50.0

Peristomalherniation 5 7.1 7.1 57.1

Pseudo-verrucouslesions 1 1.4 1.4 58.6

Allergicreactiontodevice 1 1.4 1.4 60.0

Pseudo-verrucouslesions/Dermatitis 1 1.4 1.4 61.4

Retraction 14 20.0 20.0 81.4

Prolapse 13 18.6 18.6 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Variabledemarcationwasperformed?

Yes

0.002

17 24.3 24.3 24.3

No 53 75.7 75.7 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Variabletypeofdevice

Single-system

0.043

22 31.4 31.4 31.4

Twopieces 48 68.6 68.6 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Variableirrigation?

Yes

0.047

26 37.1 37.1 37.1

No 44 62.9 62.9 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Variableitwastoldthatyouwouldhavetouseastoma?

Yes

0.049

48 68.6 68.6 68.6

No 22 31.4 31.4 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Variablestomacharacter

Temporary

0.003

18 25.7 25.7 25.7

Permanent 52 74.3 74.3 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

achangeinlifestyle;andthatthenursingcare,through edu-cational activities, is indispensable to the development of self-care and forthe adaptationofostomized people, with consequentimprovementintheirqualityoflife.28

When receiving anintestinal stoma,beyond the stigma from society, these patients suffer the embarrassment of an arduous acceptance of the changes resulting from a

Table3–ResultsobtainedinRosenbergSelf-Esteem Scale/UNIFESP-EPMandFlanaganQualityofLifeScale (FQLS)meanscoresinindividualswithintestinalstoma.

Rosenberg Self-EsteemScale/

UNIFESP-EPM

Flanagan QualityofLife

Scale–FQVS

p

Mean 10.81 26.16

0.001

Median 11.00 19.00

Mode 11 19

Standard-deviation 5.395 19.897

sexualityofthosewhoreceivedthestoma,buttoprioritize their health in all areas.30 These patients feel shame and

embarrassment,feelingsthatcangetthemtoisolate them-selvesandtoalifefullofanxiety–maybewithanegative impactontheirqualityoflife,self-esteemandbodyimage.31

Inastudywhoseauthorsidentifiedthosefactorsthat inter-feredandchangedthedailylivesofostomizedindividuals,it wasconcludedbytheanalysisoftheirreportsthat, among thefactorsidentified,changesineverydaylifeand interper-sonalrelations(especiallypartner/partnerrelationship)were included,deprivingtheindividualofagoodqualityoflife,an adequateself-esteem,apositivebodyimageandofhis/her sexuallife,thatshouldbepreservedandnotstigmatizedin society.30 Anotherstudy inwhichtheauthors assessedthe

relationshipbetweenageandqualityoflife,itwasconcluded thatolderpatients, onaverage,hadhigherscoresfor qual-ityoflife(65.21against61.87;themaximumscorewas100,

p=0.56).32

Inourstudy,afteranalyzingtheresponsesofostomized patients,themeanofRosenbergSelf-Esteem Scale/UNIFESP-EPMwas10.81.Suchfindinghascharacterizedthesepatients ashavinglowself-esteem.

Self-esteemmeans psychologicalwell-being,thatis,the patient feels satisfied with his/her life and the affections related to his/her body are positive, in that the emo-tionalresponsesarestableover aperiodoftime,reflecting acceptanceofhis/herself-image,aswell asin the adapta-tion ofprocesses arising from his/her lifecycle and social relationships.33–35

Intheprocessofadaptation,thepatientwithanintestinal stoma requires supports which are defined as interper-sonaltransformations,involvingthecombinationofaffection, socialintegration,exchangeofmutuality,asecuresenseof allianceand the meaningofguidance attainment.36 When

receivingthis support,thepatientsucceedsinhis/her self-care, which, in turn, has an effect on quality of life and self-esteem.

Fromthetimetheindividual receivesthestoma,he/she starts to experience feelings of helplessness due to the discomfort,embarrassmentandshameofhis/herbody, espe-ciallythefeelingofbeingdirtyand repugnant,37 leadingto

socialisolation,changeinbodyimageandlossinhis/her sex-uallife.

Lowself-esteemcan leadthepatienttosocialisolation, whichisvisibleintheseindividuals.However,itisimportant tostressthat,giventhisreality,itisimperativethenecessity forsocialinteraction,asthisprocess willcontributetothe

Table4–ResultsinRosenbergSelf-Esteem

Scale/UNIFESP-EPMandFlanaganQualityofLifeScale (FQLS)totalscoresinindividualswithintestinalstoma.

Total score

p RosenbergSelf-EsteemScale/UNIFESP–EPM

n %General %Valid %Pooled

1

0.079

1 1.4 1.4 1.4

2 1 1.4 1.4 2.9

3 4 5.7 5.7 8.6

4 1 1.4 1.4 10.0

5 4 5.7 5.7 15.7

6 8 11.4 11.4 27.1

7 2 2.9 2.9 30.0

8 3 4.3 4.3 34.3

9 1 1.4 1.4 35.7

10 2 2.9 2.9 38.6

11 11 15.7 15.7 54.3

12 9 12.9 12.9 67.1

13 5 7.1 7.1 74.3

14 5 7.1 7.1 81.4

15 6 8.6 8.6 90.0

16 1 1.4 1.4 91.4

17 3 4.3 4.3 95.7

25 1 1.4 1.4 97.1

27 1 1.4 1.4 98.6

30 1 1.4 1.4 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

Total score

p FlanaganQualityofLifeScale(FQLS)

n %General %Valid %Pooled

16

0.037

10 14.3 14.3 14.3

17 6 8.6 8.6 22.9

18 1 1.4 1.4 24.3

19 29 41.4 41.4 65.7

20 5 7.1 7.1 72.9

21 2 2.9 2.9 75.7

22 6 8.6 8.6 84.3

31 1 1.4 1.4 85.7

37 2 2.9 2.9 88.6

55 2 2.9 2.9 91.4

59 1 1.4 1.4 92.9

84 1 1.4 1.4 94.3

85 2 2.9 2.9 97.1

99 2 2.9 2.9 100.0

Total 70 100.0 100.0

restorationofhis/herperceptionofthebodyandself-image, mainlycontributingtoovercometheloneliness.38

Inastudywheretheperceptionofpatientswithcolostomy was analyzedregardingthe useofthecollectorbag,it was possibletorevealthefeelingsandchangesthathaveoccurred; and howtheadaptativeprocessoftheindividualbearinga colostomybagdevelops.

Itwasfoundthattherelationshipbetweenthepersonwith acolostomyand his/hercollectorbag ispermeatedby neg-ative feelingsandmajorchanges inphysical,psychological and sexualfeatures,aswellasinthewebofhis/hersocial relationships,resultinginlowself-esteem.26

Table5–Descriptivestatistics:responsesofparticipantstoitemsofFlanaganQualityofLifeScale(FQLS)inindividuals withintestinalstoma.

Questionsofthescale Scoring

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Total

N % n % N % n % n % n % n % n %

Q1 31 44.3 33 47.1 0 0.0 0 0.0 4 5.7 2 2.9 0 0.0 70 100.0 Q2 47 67.1 15 21.4 0 0.0 3 4.3 0 0.0 5 7.1 0 0.0 70 100.0 Q3 50 71.4 10 14.3 2 2.9 2 2.9 1 1.4 0 0.0 5 7.1 70 100.0 Q4 28 40.0 34 48.6 2 2.9 1 1.4 0 0.0 1 1.4 4 5.7 70 100.0 Q5 32 45.7 28 40.0 2 2.9 3 4.3 2 2.9 1 1.4 2 2.9 70 100.0 Q6 51 72.9 8 11.4 3 4.3 1 1.4 2 2.9 3 4.3 2 2.9 70 100.0 Q7 49 70.0 13 18.6 2 2.9 1 1.4 0 0.0 2 2.9 3 4.3 70 100.0 Q8 55 78.6 10 14.3 1 1.4 0 0.0 0 0.0 2 2.9 2 2.9 70 100.0 Q9 55 78.6 9 12.9 1 1.4 2 2.9 1 1.4 0 0.0 2 2.9 70 100.0 Q10 51 72.9 11 15.7 1 1.4 2 2.9 1 1.4 2 2.9 2 2.9 70 100.0 Q11 62 88.6 0 0.0 1 1.4 3 4.3 0 0.0 2 2.9 2 2.9 70 100.0 Q12 54 77.1 8 11.4 3 4.3 0 0.0 0 0.0 3 4.3 2 2.9 70 100.0 Q13 62 88.6 2 2.9 0 0.0 1 1.4 1 1.4 4 5.7 0 0.0 70 100.0 Q14 58 82.9 4 5.7 1 1.4 2 2.9 0 0.0 4 5.7 1 1.4 70 100.0 Q15 57 81.4 4 5.7 1 1.4 0 0.0 2 2.9 6 8.6 0 0.0 70 100.0

Q1,Materialcomfort:housing,food,financialsituation;Q2,Health:tofeelphysicallywellandwithenergy;Q3,Relationshipwithrelatives,social coexistence,communication,helping;Q4,Familyconstitution:havingandraisingchildren;Q5,Intimaterelationshipwithspouseorpartner;Q6, Relationshipwithfriends;Q7,Helpingandsupportingothers;Q8,Participationinpublicinterestassociationsandactivities;Q9,Apprenticeship: havingtheopportunitytoincreaseyourgeneralknowledge;Q10,Self-knowledge:knowledgeaboutyourpotentialsandlimitations,toknow whatyouwant,importantgoalsforyourlife;Q11,Occupationatworkorathome;Q12,Knowshowtocommunicate;Q13Participationin recreationalandsportsactivities;Q14,Listeningtomusic,WatchingTVormovies,readingandotherentertainments;Q15,Socialization:make friends.Independence:feelabletodothingsforyourself.

Table6–ResultsobtainedinFlanaganQualityofLife Scale(FQLS)meanscoreinindividualswithintestinal stoma.

Itemsofscale Scoring

n Mean Median Standard-deviation

Q1 70 1.84 2.0 1.187

Q2 70 1.70 1.0 1.387

Q3 70 1.77 1.0 1.661

Q4 70 2.00 2.0 1.474

Q5 70 1.94 2.0 1.371

Q6 70 1.74 1.0 1.567

Q7 70 1.69 1.0 1.499

Q8 70 1.49 1.0 1.316

Q9 70 1.47 1.0 1.224

Q10 70 1.64 1.0 1.435

Q11 70 1.47 1.0 1.411

Q12 70 1.59 1.0 1.440

Q13 70 1.41 1.0 1.291

Q14 70 1.54 1.0 1.431

Q15 70 1.63 1.0 1.534

Q1,Materialcomfort:housing,food,financialsituation;Q2,Health: to feel physicallywell andwith energy; Q3, Relationshipwith relatives,socialcoexistence,communication,helping;Q4,Family constitution:havingandraisingchildren;Q5,Intimate relation-shipwith spouseorpartner;Q6,Relationshipwithfriends; Q7, Helpingandsupportingothers;Q8,Participationinpublicinterest associationsandactivities;Q9,Apprenticeship:havingthe oppor-tunitytoincreaseyourgeneralknowledge;Q10,Self-knowledge: knowledgeaboutyourpotentialsandlimitations,toknowwhatyou want,importantgoalsforyourlife;Q11,Occupationatworkorat home;Q12,Knowshowtocommunicate;Q13Participationin recre-ationalandsportsactivities;Q14,Listeningtomusic,WatchingTV ormovies,readingandotherentertainments;Q15,Socialization: makefriends.Independence:feelabletodothingsforyourself.

allhumanbeingsconstruct,throughouttheirlife,animageof theirownbodythathastodowiththecustomsandthe envi-ronmentinwhichtheylive,inordertohavetheirneedsmet andtobesituatedintheirownworld.Bodyimageislinkedto conceptsofyouth,beauty,vigor,integrityandhealth. There-fore,thosewhodeviatefromtheconceptofbodybeautymay experiencefeelingsofrejectionandexclusion.39

Inastudythatevaluatedtheimpactofastomainpeople’s lives,theauthorsconcludedthatwhenapersonreceivesan intestinalstoma,severalchangestake placeinthelifestyle oftheseindividuals,involvingtheneedforlearningself-care or changes in relation toits lifestyle with respectto their socialparticipation,aswellassexualimplications.Anyway, the fearthatthe individual hasaboutthis unknown situa-tioninvolvesthedevelopmentofanintimateandpsychosocial discomfort.40

Thus, the person that received an ostomy should not understandtheostomizationasahindrancetohis/hersocial andsexuallife,butasanewconditionneedingadjustment. Giventhattheoccurrenceofanychangeisdifficult,the pro-fessionalwho isprovidingcaremustgohandinhandwith his/herpatient,sothatinthiswaythepatientfeelssupported andwillingtoseekhelp.41

Consideringtheneedsthatemergedinrecentdecadeswith theincreasingnumberofpatientswithchronicdiseasesthat canleadanindividualtolivewithanintestinalstoma,itis essentialto redirectour academictraining and the qualifi-cationofourhealthprofessionals,emphasizingnotonlythe content,butalsothepracticeofcareofferedtothesepeople. Anditisalsocriticalthattheseprofessionalsbecomeaware oftheimportanceofostomizedpeopleperformingself-care.

Conclusion

Patientsinthisstudyshowedlowself-esteemandqualityof life.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1. SampaioFAA,AquinoOS,AraújoTL,GalvãoMTG.Nursing caretoanostomypatient:applicationoftheOrem’stheory. ActaPaulEnferm.2008;21:94–100.

2. CascaisAFMV,MartiniJG,AlmeidaPJS.Oimpactodaostomia noprocessodeviverhumano.TextoContextoEnferm. 2007;16:163–7.

3. CesarettiI,ViannaLAC,ShiftanS,SantosVLCG.Qualityoflife ofcolostomypeoplewithandwithoutplugsystemuse:1426. JWoundOstomyContNurs.2007;34:S67.

4. CiconelliRM,FerrazMB,SantosW,MeinãoI,QuaresmaMR. Traduc¸ãoparaalínguaportuguesaevalidac¸ãodo

questionáriogenéricodeavaliac¸ãodequalidadedevida SF-36(BrasilSF-36).RevBrasReumatol.1999;39:143–50.

5. McCleesN,HylandD,BoltonL.Qualityoflifewithanostomy: historicperspective:1444.JWoundOstomyContNurs. 2007;34:S72.

6. AvanciJQ,AssisSG,SantosNC,OliveiraRVC.Adaptac¸ão transculturaldeEscaladeAutoestimaparaadolescentes.Rev Psicol:ReflexãoeCrít.2007;20:397–405.

7. ItoN,IshiguroM,UnoM,KatoS,ShimizuS,ObataR,etal. Prospectivelongitudinalevaluationofqualityoflifein patientswithpermanentcolostomyaftercurativeresection forrectalcancer:apreliminarystudy.JWoundOstomyCont Nurs.2012;39:172–7.

8. SaloméGM,PellegrinoDMS,BlanesL,FerreiraLM. Self-esteeminpatientswithdiabetesmellitusandfoot ulcers.JTissueViability.2011;20:100–6.

9. HerdmanM,Fox-RushbyJ,BadiaX.‘Equivalence’andthe translationandadaptationofhealth-relatedqualityoflife questionaries.QualLifeRes.1997;6:237–47.

10.RosenbergM.Societyandtheadolescentself-image. Princeton,NJ:PrincetonUniversityPress;1989.

11.RosenbergM,SchoolerC,SchoenbachC,RosenbergF.Global esteemandspecificself-esteem:differentconcepts,different outcomes.AmSociolRev.1995;60:141–56.

12.SouzaDBL,FerreiraMC.Autoestimapessoalecoletivaem mãesenãomães,10.Maringá:PsicologiaemEstudo;2005.p. 19–25.

13.DiniGM,QuaresmaMR,FerreiraLM.Adaptac¸ãoculturale validac¸ãodaversãoBrasileiradaEscaladeAutoestima Rosenberg.RevSocBrasCirPlast.2004;19:41–52.

14.FlanganJC.Measurementofqualityoflife:currentofart state.ArchPhysMedRehabil.1982;23:56–9.

15.Gonc¸alvesLHT,DiasMM,LizTG.Qualidadedevidadeidosos independentessegundopropostadeavaliac¸ãodeFlanagan.O MundodaSaúde.1999;23:214–20.

16.BarrosEJL,SantosSSC,LunardiVL,LunardiFilhoWD.Ser humanoidosoestomizadoeambientesdecuidado:reflexão sobaóticadacomplexidade.RevBrasEnferm.2012;65: 844–8.

17.MeirellesCA,FerrazCA.Avaliac¸ãodaqualidadedoprocesso dedemarcac¸ãodoestomaintestinaledasintercorrências tardiasempacientesostomizados.RevLat-AmEnferm. 2001;9:32–8.

18.CesarettiIUR,SantosVLCG,ViannaLAC.Qualidadedevidade pessoascolostomizadascomesemusodemétodosde controleintestinal.RevBrasEnferm.2010;63:16–21.

19.AnarakiF,VafaieM,BehbooR,MaghsoodiN,EsmaeilpourS, SafaeeA.Qualityoflifeoutcomesinpatientslivingwith stoma.IndianJPalliatCare.2012;18:176–80.

20.KosovanVM.Comparativeestimationofqualityoflifein patientswithcolostomy.KlinKhir.2013;4:8–51.

21.FortesRC,MonteiroTMRC,KimuraCA.Qualityoflifefrom oncologicalpatientswithdefinitiveandtemporary colostomy.JColoproctol.2012;32:253–9.

22.NakagawaH,MisaoH.Effectofstomalocationonthe incidenceofsurgicalsiteinfectionsincolorectalsurgery patients.JWoundOstomyContNurs.2013;40:287–96.

23.KellyC.WOCnurseconsult:peristomalcomplication.J WoundOstomyContinenceNurs.2012;39:425–7.

24.BatistaMRFF,RochaFCV,SilvaDMG,JúniorFJGS.Self-image ofclientswithcolostomyrelatedtothecollectingbag.Rev BrasEnferm.2011;64:1043–7[Brasilia].

25.CunhaRR,FerreiraAB,BackesVMS.Características

sociodemográficaseclínicasdepessoasestomizados:revisão deliteratura.RevEstima.2013;11:29–35.

26.BatistaMRFF,RochaFCV,SilvaDMG,JúniorFJGS.Autoimagem declientescomcolostomiaemrelac¸ãoàbolsacoletora.Rev BrasEnferm.2011;64:1043–7.

27.BarbuttiRCS,SilvaMCP,AbreuMAL.Ostomia,umadifícil adaptac¸ão.RevSBPH.2008;11:27–39.

28.NascimentoCMS,TrindadeGLB,LuzMHBA,SantiagoRF. Vivênciadopacienteestomizado:umacontribuic¸ãoparaa assistênciadeenfermagem.TextoContextoEnferm. Florianópolis.2011;20:557–64.Jul-Set.

29.GemelliLMG,ZagoMMF.Ainterpretac¸ãodocuidadocomo ostomizadonavisãodoenfermeiro:umestudodecaso.Rev Lat-AmEnferm.2002;10:34–40.

30.GomesIC,BrandãoGMON.Permanentintestinalostomies: changesinthedailyuser.RevEnfermUFPEonline. 2012;6:1331–7.

31.PittmanJ,KozellK,ShouldWOC.Nursesmeasurehealth relatedqualityoflifeinpatientsundergoingintestinal ostomysurgery?JWoundOstomyContNurs.2009;36: 254–65.

32.WongSK,YoungPY,WidderS,KhadarooRG.Adescriptive surveystudyontheeffectofageonqualityoflifefollowing stomasurgery.OstomyWoundManage.2013;59:16–23.

33.FreitasMRI,PeláNTR.Subsídiosparaacompreensãoda sexualidadedoparceirodosujeitoportadordecolostomia definitiva.RevLat-AmEnferm.2000;8:28–33.

34.SaloméGM,deAlmeidaSA.Associationofsociodemographic andclinicalfactorswiththeself-imageandself-esteemof individualswithintestinalstoma.JColoproctol.

2014;34:159–66.

36.SantosVLCG.Fundamentac¸ãoteórico-metodológicada assistênciaaosostomizadosnaáreadasaúdedoadulto.Rev EscEnfermUSP.2000;34:59–63.

37.LuciaSC.Sexualidadedoostomizado.In:SantosVLCG, CesarettiIUR,editors.AssistênciaemEstomaterapia:cuidado doOstomizado.SãoPaulo(SP):Atheneu;2005.

38.SbicigoJB,BandeiraDR,Dell’aglioDD.Escaladeautoestima deRosenberg(EAR):validadefatorialeconsistênciainterna. PsicoUSF.2010;15:395–403.

39.SilvaAL,ShimizuHE.Osignificadodamudanc¸anomodode vidadapessoacomestomiaintestinaldefinitiva.RevLat-Am Enferm.2006;14:483–90.

40.OliveiraG,MaritanCVC,MantovanelliC,RamalheiroGR, DavilhiaTCA,PaulaAAD.Impactodaestomia:sentimentoe habilidadesdesenvolvidosfrenteànovacondic¸ãodevida. RevEstima.2010;8:18–24.

41.SalimenaAMO,ValenteWR,MeloMCSC,PashoalinHC,Souza IEO.Compreendendoasvivênciasdemulheresaoenfrentara condic¸ãodeterumestomaintestinal.RevEstima.