F UNO A ç Ã O

GETULIO VARGAS

FGV

EPGESEMINÁRIOS DE ALMOÇO

DA EPGE

Measuring the TFP costs of barriers to

trade

PEDRO CAVALCANTI FERREIRA

(EPGE/FGV)

Data: 02/06/2006 (Sexta-feira)

Horário: 12h 15 min

Local:

Praia de Botafogo, 190 - 110 andar

Auditório nO 1

Coordenação:

l\:1easuring the TFP costs of barriers to trade

Pedro Cavalcanti Ferreira"

Alberto

T'rejost

EPGE - Funcla(;âo Getulio Vargas

INCAE

April 28, 2006

Abstract

Thís arLicle performs outpnt decompositiolls in ol'del' to meaSUl'e

the eJ1ect of trade restrictío11s on total factor procluctívity anel labor

productjvity. lt is assumed an ecollomy with two traclable and

1l01l-storable intermediate goods, used in the production of a. nOll-tradable

flnal good. The solution of the sLalic Lracle anel fador allocation

prob-lem generates implicitly a mapping between factor endOvvmenLS and

flnal output, which is then l1sed as an exogenous prodnctíon

fUllC-ti011 in the decomposition exerci se. vVe find that for lllidclle income

economies vúth high tarilI rates, the effects 01' tracle restrictions are

sigllificant; in some cases, enough to a.ttribute to protectionism Olle

thil'd of lheir TFP disadvantage, OI' Luore. For lhese cconomics, the

impacl o[ trade rcstrictiolls on GDP per worker iH aIso l'ekvant.

,

-'Praia ele Botafogo, 190, Rio de Janeiro,RJ, Brazil, 22253-900. ffTTeinl,((}fr;v.!J'r t Apartado 0GO-4050, Alajuela, Costa Hica. albcTto. tTé)osrfl'incac. cd'u

1

Introduction

vVe study and measure the eífects of international tmde paliey on LotaI

fae-{.or product.ivit.y and output leveIs. As opposed to the prevíous development

nceonnting liLcnüure1, \ve are not \vorried whether TFP 01' factoni are Inore relevnnt. in explaining output difl'erences. Instead, we perform outpnt

de--compositiOl iS frorn a distindive perspcdive. \Ve are interesLed to estirnate in

the lirst pInce thc share of TFP difference that is due to distOl'tions cnused

by harrÍcrs to 1.rade. 0111' lnodel is adeqnate t.o this task hecause in essence

its trade portion is Lhe standard Hecksher-Ohlin moclel. TaríH's distOl't

do-mestíc priccs introducing; an inefficiency in the allocation

01'

fadol's betweenthe proctnd ion of inLermediaLe goods, tIms redncíng the value of national

ーイッ」QャjHセエ@ at internationaI prices. In addition, the same price dist.ortion causes

<tu inefficiclJ(;y in the c110ice of the mix of inLcrrnediatc good hy .t:inal-good

procl!lcers.

Hence, policy instrulllents that incl'case the cost

01'

lnternational tradegenerate ,tn inefficicnt equilibrium allocation of factors aeross industries. In

t,he lllodel, r:his inefficieney lIas an eHect similar to a [aIl in total factor

pro-dlldivily. l'nder a eOllservative calibration of the pal'ameters that determine

the a.ggl'ega':.e, statíc importance of trade, we find that barriers to trade C<:tIl be ver)' impxtant for poor countl'ies. Incteed, the model says Lhat for a

COUIl-1 For inSÜtl'Ce, lVIallkiw, Romer anel "Veil (1992) anel Mankiw (1995) present.eei evidellce

t.hat ヲ。」エッイセZ@ (, f prodnct. iou HCCOllUt for the bnlk of i UCOllle di ffercnces acrOf:f: 」ッョョHNャᄋゥ・セZN@

try WiUl 1/4 of U8 capital/labor ratio, the sLatie elifference bdween having tarifI leveI of 10% OI" 100% can represent. a 10ss of output. of 8.7%.

Apply-ing t.he rnodel 1.0 the data of some countries'Nith a protccLionist past - Lhe main excrcise of this art.icle - \ive find that as much as one thirel of their TFP

ditfercnce rei ative to the U8 ca,n be attribllted Lo restrÍctive t.rade poliey.

Although this is the 1110st elramatic result, we fóund sÍzable productivity anel

ontpllt eost.s

oI

barriers to trade in Iuany cases.vVe use as ou!' main insLrument a model that follows Ferreira anel Trejos

(2006). In this framework, it is assumecl an econorny with L\vo tradable anel non-stol'able intermeeliate gooCl<3, used in Lhe product.ion of a nOll-tradnble

final good. vVe focus OH the case 01' a small, príce-taking economy. The

so-Illtion of the static tmde anel factor aLlocation problem genel'ate:s implicitly

a mapping between facto!" enelowments anel final output, \vhich cem then be

uHed as ,Ui exogenous productlon fuuction. '[,his (ixmulation is similar to Cor-den (1971), Trejos (1992) anel Ventura (1997) thaL use a fador-endowrnentH framework to introduce t.rade in a macro model.

This artide has fonr sessions in adelition to Lhis introduction. The ncxt session present.s the model used in our development decomposition exercises,

whilc sesslon three discusses data anel calibration. 8ession four pre:sents the

T'ime is disnete and unhonnded. Our representative count.ry i8 small (a price t.aker) anel populat.ed by a continuum of identical, illfinitely-lived individuaIs.

There are three goods produced in this economy. Two of those goods, called

/1

anel B, are non-stol'able, tradable intermediate produds. They are oulyused to Inal:e the other good, called Y, a final produet that can be consumed

01' invest.ed, but that CéUmot be traded. There are a180 tvvo factors oi" pro-dm:Llon in l.his economy: labor in efficient nnits H and physical capit.al }{.

]'he endow1llcnt oI" labor, mea,sured in efficiency units, 1S given by:

\vhere li repI'esents eificiency-units oflahor per \vorker and s stands for schoo1·· ing. The production functio1l8 of A. and B are:

Wit.hout ャッセウ@ of generality, A i8 labor-illtensive: (ta

<

0b. The production 01'the fhml good Y llfles only the intcnnediate goods. Becamc t.hese

intennedi-ate gooels are traelab1e, the amounts of t.hem that are used in the production

oI" the flnal Lャセッッ、@ (denotcd by lmverease a and

b)

may difIer from the amOllntsproduced A anel B. Tbtal ontpnt of Y is given by:

(1)

'2The l11CHk] follows closely Ji'erreíl"a and Trejo .. s (2006) anel hence ít wíll on]y be presenteel

vrhere 8 1S total factor productivity.

VVe derive the allocation of capital K anel labor I1 aUlong the productioll

01'

A

and B, Lhe quantities (J, anelb

of intermediale gooels nsed domeslically,and the amount

01'

final outputY

thaL is produced. Because intennediategoods are assumed t.o be l1on-slorable, and tbe lim-l.l good is nol lradable,

lhis i8 a static l)l'Oblel1l, which yields all equilibriul1l l1lapping

Y = F(I{, HIT,

p)

that relates final oulput with factor endmvments. Second, because factors

are not tradable, we can simply use that equilibrium mapping

F

as if it ,;verean exogenonsly given lechnology.

To get Y =

F'

(K, HIT,p) in equilibrium notice that each period, theequilibrium solntlons for

{A,

B, 0"b,

q. V), T,Ki,

Hd

must satisfy t,he followingproperties:

1. Producers

01'

intermediate goods chooseKi. Hi

In order to maxnmze the period's profit,s:n:

A2. Producers of .flual goods IIlé1Jemuze profits, taking domestic pnces as

glven:

l -"ll--, l

a, )

=

argmaxíla') ' -qa - )a,l;

:3. Finnt-' make zero profits,

qa

-+

bqA

B

marh:ts dear,

anel n;:;ents neither bOITOW from nOI" lencl to the world economy,

pA+ E

=

pa-+

b.'1. Local priccs

01'

tradable goods satisfy ali afLer-tnrifI law of one price:q = { p/

(1

-+

T),

p.(1-+T) if

if

a<A

Hascel Oll these requisites, one cnn derive Lhe equilibrinm relationship F:

1. lf li' / fi is much lmver [nu1<,:h higher] than t,he world's raL io ({{ / 11) * ,

onl)' the intermediate セッッ、@ A

[El

will be produced, as its productiolluses more intensively the relatively abundant labor [capital]. There are

criticaI leveis 8}

<

(J{

/

H)*

and ,Z2>

(J{

/

ITr

sueli that ifIC

/ H

S

81then t he country onl;tj produces A, and if K / H

?

Z2 then the countryonly prodnces

n.

'I'hen, Y is a Cobb-Donglas fnnction oI {( and H,are sen:útive to T. In particular, with higher Lariffs the ecoIlomy is less

pronc to specialize, so

D"hIDT

<

O[DzdDT

>

OL with -s[ -+ O {N_Zセ@ -+ cX,.;]as T -+ 00.

2. If

1-:1

II1S

very dose to (KI

11)* a high cnough tariff wi11 makc the ecoIlomy noL trade at aU: There exist :E1 and [iZセL@ where s[<

:rlS

thel'e is no Lrade, so

a

= ./1,b

=

B.

\;Ye have:D:EdDT

< O a.nelD:.c'2/DT

>

O. Also, Xl -+ O anel ::C'l -+ 00 as T -+ 00, \vhile Xl = :E2 if T = O.

:3. Ifh,/H is neither too dose llor too far from (lo(

/1-1)*,

Lhe eCOl1omy wiU proeluce both intermeeliate goods, yet still Ü'aele. In thosc cases holelsa result analogous to the Fhdor Price Equél.lization Theorem, \vhich

states thaL equilibrium marginal returns of capit.al anel labor are not

sen:-;itive to small wtriations in the fador eudowl11.ent. Wlmt that means is Lhat tillal output

Y

is linear in [( anelH

wbenK

I

H

E [81,:Ed

01'vvhen K/H E [:E2, Z2]'

h・jャHセ・L@ Lhe eqnilibrium relaLionship frolll

T-:

anelH

t.o l' takes Lhe fonnF'(K ,

Hlr

- , J)) I =n

1KO"H1'''O!a if K/H<

SIoセiH@

+

O:lH if K IH Hセ@ 181, ;1;11[241('iH1-ci if KIH E [Xl,X2]

where the values

Di.

are functions of parametel's, anel are afledeel by p anelT. For a dosed economy it is Lhe case that [:1:1, :X:2) := \Jt+. Con:-;cql1enLly,

with-out trade our l1lodel simply collapses to one with the aggregate production

funclÍon

F"'(1\", HIT,p)

=

Du

1I(ê'H1-ct ,.a

equal to"'ret

a+

(1 -1)

rl"b. For <-111values of p anel T, F is homogcneous of degl'ee one anel continuous in K and

H. Ccncricnlly, F 1S also locally concave and continuously eliITerentiable.:1.

F i8 ・ャ・」イ・。セ[ゥョァ@ in T (strictly elecreasing if k セ@ [:1:1,

X2])

anel also DF!\ / DT<

O.The fac!. that

a

F[( /ar

<

O implies that a protectionist Lrade policy carries as a conscquence a loss in output, given inputs, anel thereforc a 10ss inmea-sured prodndiviLy. T'he eiTect of r on ouLpuL is not because tariffs appear

directly in <tny of 1;l1e proeludion fllnctions, hn(; rather hecanse tarifIs change

domestic prices in a way that distorts the decisions of produccrs. The1"e are

t\vo reasons \vhy this is so. First, a distorted q inlrodnces an incHiciency

in the allocation of J{ anel H betvvcen A anel B, thus reelucing the value of nation.al produd at international prices. Second, the same price distortion

causes an illeíIiciency in the choice of a anel b by Y-producers.

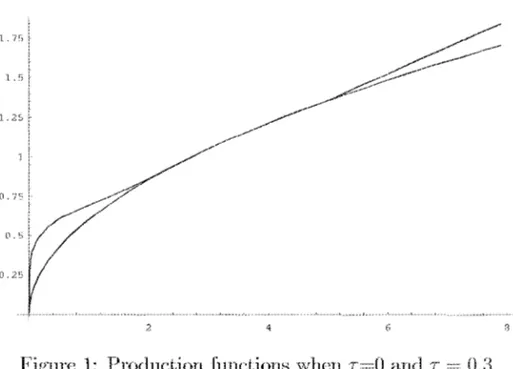

'file thüxet.icnl e[Técts of t.aritTs on outpnt are iHusLmted in Figure 1, for

the case vvhere T

= ()

and r =::: HINセゥL@ respectively.3U T .> O )2;lobal concavi1y anel continuous differetltiability is lost becau"e FI( has

diserete variatíons (l1p Ol' elown) at the criticaI yalnes 8, and cc,. See Ferreira anel Trejos

1.7S

1.S

1. 2ó

0.75

o.s

Q.25

4

Figure 1: Prodndion fundiom; when

T=O

anel T=

0.3Note that., gIven

K/ H,

the open ・」ッョッュセt@ unambiguously obt.ains moreoutput as

F(IC I1IT

>

O) iH everywhere belowF(I.;,', BIT

=

O). T'his meansthat in thÍs n1.odel, everything else eqnals, larger barriers to trade imply

smaller prodnctivit,y. Moreover, the larger T, Lhe larger Lhe disLance bct,ween

F(IC HIT

>

O) anelF(K, HiT

=

O), givcn K anelH.

Note also Lhat 1,he1"eis all interval [:r] ,

T2l

where the curves coincide. In this sense, the modelpredids that t,hc costs of protectionism for econornies dose Lo the lcadcrs is

either null or very small, vvhich is what one conld expect from a model in

wbich trade iR driven by eornparaLive advant,age.

We perform level-accolUlting exercises for a variety oi" countrics, to see

whaL frnct,ion oI the Lotéil fador prodndiviLy reRidnnI LhaL one mensures

usíng a dosed-economy fn.nnevllOrk c<tn ac1,ually he aLtribnLcd to the

ineftl-ciencÍes associated with protectionist trade policy. In this sense ours is a

impact of i hese balTiers on capital accuIlllllation anel hellce on grO\vth anel

income levds in the future. As ".Te have SbO\Vll in our previous paper, t,his 10ng 1'un ・ヲェ[サクセエ@ of protcctionism policy can be sÍzable. Howcver, \ve 1'esLrict

ourselves t() the ヲッャャHョ[カゥョセ@ decomposition cxercise:

lnClus/Ui) In (F(k;,

hilnTs))/

ln(F(k;, h;ITl ))+

ln(F(ki1

husITus))/ln(F(kj , hjITCS))+-In (F(ku,5, husITUS))/ ln(F(ki , hos,ITus))

+

ln((yus/ F(kus, liusITUS))/(y,:/F(ki , hiIT,:))),

where y and k stanel for ouLput per worker anel capital per worker,

respec-tively. By LセZッョウエイオ、ゥッョL@ the snm in the right hanel size has to he eqnal to

the left hand sÍze. 'rhe latt.er is the ratio of US GDP per worker to

COU11-Lry i's GD1) per 'worker. The lirsL expression to thc right is the portioll of

GDP diHel'f'.llce explained only by tariffs. vVe use our production function

to measure cHltpnt, \vith the respective factors

01'

prodndion, bnt we giveto eountry; the tarifIs observecl in the

USo

Thc second expression gives theresidual diflérence

01'

output - artel' accOlmting for trade poliey - expIained hyhllman capital dispariLies. The third expresslon gives l.he residual

dilTerence-aftel' accoullting for trade and educational disparities- explained by physical

capital. Th" expression in the very bottom is Lhe residual TFP elitIercnce, iL

is that part of TFP disparity which is not explainecl by tracle policy.

3

Data and calibration

To assess h, we use a standard Mincer function of schoolillg,

01'

the fOl'lnh

=

e08 . Follmving Psacharopoulos (199/1), we set. t-he return of schoolingto

q)

=:: 0.099. \!Vc used data OH the average edllcational atlainment 01' 1.he population aged 15 year8 and over, takell from Barro and Lee (2000)4.\!Ve use the Penn-\Vorld Tnblet'i (PWT) dala for output per workcr. The

physical capital series is construded with real investment. data from the

P\!VT' usÍl1g the PerpetuaI Inventory l\Jethod. 'lhe inibal capital stock, ]{o,

was approxÍmated hy ](0

=

Io/[(l

+

.17)(1

+-

17,)

-

(1 -â)],

where lo Ís the initial investmenL expenditure, 9 i8 the rate of technological progress andn 18 Lhe growth raLe oI' the populaLion. In t,his calculaLion it is assmned that alI economies were in a balanced gTOIvth pat-h aI, time zero, so that

L_j

=

(1-+

nr-

j (1-+-

gr-

j lo·\Ve use thc same depreciation rate for alI economies, which was calculated

from

lJS

data. \!Ve employed the capit.al slock a1. market Plices, invcst.mentat Inarket prices, I, as well as the law of lllOtioll of capital to estimat.e the

implicit. depreciation rate according to:

From this calculation, wc obtaincd â

=

3.5% per year (average of the1950-2000 period). To minimize Lhe impact of economic Dllctna1.ions we uscd the

average investment of the first fíve years as a mcasure of lo. \!Vhen data was

availnble we starLed this procedure taking 1950 as 1,he iniLial. year iH mder Lo reduce the efied of I(o in the capital stock series.

4 Data ,vere interpoJated (in levels) to fit an annual frequency when necessary.

Trade pnlicy is assessed with many alternalive data sources. '\Te flrst uscd,

for i,he mid 19(;0's and mid

U)80's,

data from individual country studies. InLhe finlt ca3e we nsed data from Balassa (1971) which constrnded, for a

very limited number of countries, series of efIective rate

01'

protection. Fortbe seeond period we nsed data from Feneira anel Rossi (2001)

ror

Braz i! ,gッョコ。ャ・コMvイセァ。@ auel l\10nge (1995) for Costa Rica, Harrison (1994) for Ivory

CoasL, anel vVorkl BalJk

(Um3)

for Tbailand. In 11.11 cases these mensures01'

ーイッエ・、[ゥッョゥセュ@ \vere converted into T-equivalent terrns. vVe also Hsed \\Torld

Bank(200G) data on avcrage tariff rates (unweighted). Althongh nominal

tariff is a 'worse rneasure of protedionisnl than efTeetive raLe

01'

proteetion, inthe presellt case it has the advantage of being available for a large number

01'

connLries.We interpret the large economy in steady state to be the U8; hence, we

replicaLc Lhe standard calibration of tbe AnlCl'ican economy in dosedRBC

models USil!.g f(k) セ]@ [Llkü. FoUowing NIPA figures for capital's sharc in l1RtÍonal income, we also match ê'f = 1/3 This pins down the average Q, but

leaves frecduHl in choosing '''y', Cta and O'/J. These parameters are particularly impodant, HS the quantitative effects of aU trade-l'elated phenomena, for low

k, are bound to bc larger with a big spread (li/) ---- na, anel with a lower i,

given Q.

If

bot-11 industl'ies requirc very different capital labor raLios, thereis nmch to he gained from trade, as each cOlUlLry can specialize strongly on

the industr.\- whosc demand is dosest to their endO\vlnent. We choose (V(L) C1!b

anel i so that expol't.s cannot amount t.o more than hal1' ot' output, anel so

tha!', for セュ|イ@ one 01' Lhe 20 richest eonntries in the world in laRG, the LotaI

gaius t'rom Lracle (the clifference between T

=

ex) anel T=

O) are ê1,t most 1%

of toLal outpUL. This leads to ,../

=

1/2, eLa=

0.258 anel Ob = OAOS. Hesnltsare robust to varÍatíons of these values within rcasonable bounds.

4

Results

"Ve find that for many countries the effect of trade polícy ís negligible, because

they have low tarifIs, 01' because they are relatively wealthy compared to Lhe

USo Similarly, for many extremely poor countries, the eflects of tarifis are

large compareci to their own lo"v income, but only fi. very smaU fraction of

their productivity difference with respect t.o the US, which is also very large.

Ncvertheless, for some middle inconw economies with high tariff ratcs, Lhe

effects are significant; in some cases, enough to at.trihute to protectionism

one thircl of t;heir

TFP

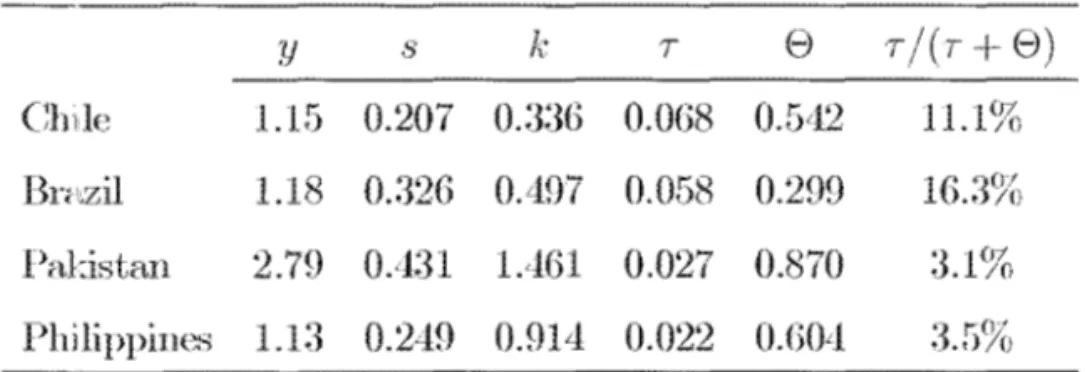

disaclvant.age, 01' more.Tablcs 1 anel 2 show eompariSOl1Swith Lhe lJS for some cOlLnLries in Lhe

mid 1960's and mid 1980's. The column labellecl li shows log-diflerences in

output relRtive to Lhe

tiS,

anci the columns labelleel 8, k, 7 and 8 are theportioll of those log-differences t.hat cau be at.tributed to schooling, capit.al,

protectionism anel produd,ivit,y, respectively. They should, of course, adel up

to the value shown in column li, as saicl belore. The last COIUlIlll measures the proportion of t.otal residual

(7

+

8) explained by tariff dístortions aloue.y S I" 1..

,

8

,/(T+8)

Chile 1.15 0.207 0.336 0.OG8 0.5,12 11.1%

Bn'czil 1.18 0.326 0.497 0.058 0.299 16.3(/;) Pabstan 2.79 0.431 l.'ct61 0.027 0.870 3.1%

Philippines 1.13 0.249 0.9H 0.022 O.GO'! ') r'O'1 d.d/o

y

..,

k:,

8

,/(, +

8)

---Costa Rica 1.25 fJ.:329 0.66 0.04:3 0.216 lG.5%

Brazil 1.07 0.'135 0.438 0.077 0.121 38.8%

Ivory Coast 2.62 0.46 1.81 0.061 0.287 17.0%

Th"jla,nd 2.()Ll 0.339 0.793 0.0:32 0.871 lWセ[サI@

\Vé ean see that pl'oductivity 108s due Lo tarifls is significanL in SOlne

cases, especially for the middle-income eonnLries. In Brazil in the 1980's, T

explains ahnoRt ,10% oi' the TFP diflerence 'ivith respect to the

lTS,

vvhich isllot surprising as Brazil in Lhe period was one of the closest eeonomy in Lhe

"vorld. In other cases as Costa Rica, Ivory Coast anel Chile in the 1960's,

protection also have relatively large etTects 011 prodllctivity gap.

or

coursc, itcarmot explain the bulk of per worker income difference in a given lllmnent,

but the ・ョセG」エ@ OH TFP is sizable.

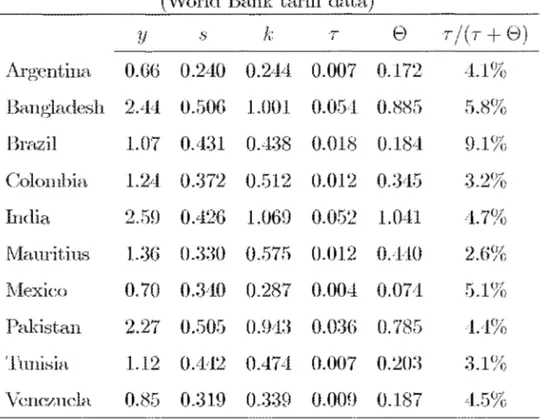

Table 3 bdow presents results also for mid 1980's now l1sing \iVorld Bank

data on aVt'l'il,ge tarifI rates. AR saicl before, this serics lIas the advantage 01'

Table :3: Diíferences in output rclative to l,he US, mid 1980':-;

(World Bank tariff data)

y .s k . .,-, 8 T/(T

+

8). .

.

Argentina 0.66 0.2L1O 0.2/fLl 0.007 0.172 ,1.1%

Banglade:-;h 2A4 0.50G 1.001 0.054 0.885 5.8%

Brazil 1.07 0.'1:31 0.'138 0.018 0.18·c! 9.1 c[セI@

Colombia 1.24 0.372 0.512 0.012 0.:345 3.2%

India 2.59 OA26 1.069 0.0;52 1.041 セQNWE@

Mauritius 1.:3G 0.330 0.575 0.012 0.,,140 2.6%

Mexico 0.70 0.:340 0.287 0.004 0.074 5.1%

Pakistan 2.27 0.505 0.9Ll:3 0.0:36 0.785 ,1.'1%

Tnnisia 1.12 OA42 OA74 0.007 0.203 :3.1%

Venezuela 0.85 0.:319 0.:3:39

O.OOU

0.187 ·'1.5%The countries above were purposely chosen due to the larger effect of

T. However, even m these cases Lhe impaeL of trade barrlcrs were noL 1,00

sizable. Only in Brazil it explains something dose to 101)()

01'

the TFP gap.In other cases, sueh as Bangladesh, セiGi・クゥ」ッ@ anel Incha, the observcd average

エ。イゥhセBャ@ \vere Lhe cause

01'

5% of the TFP difierence. l'dost. of the rclevant caseswere Inidle-income economies in Latin America and Asia, in which measured

tariffs "vere higher. In aU

OECD

countries, as expected, t11e impad was doseto zero: trade clue to compara tive aclvantage is not the main reason for them

to trade, so 1,hat ou1' rnodel cannot capLnre thc cos1,

01'

Lrade harricl"s. In vcrypoor economies the measured impact was also small.

There are Lwo reasons we ca.Il conjeeture for the impact of T t.o bc relat.lve snlall in the above table, although llot irrelevant in mau}' cases. One is that

this mensure under-estimate the degree of protection. For iwstance, it does

1101, take inlo accOlmt the fact that in the mid 1980's non t.rade barriers such

as cotas, li(:ensing 01' outright ban on the import of specific prodncts were \'lideiy used anel 1110st probably were more important for trade protection

1,ha11 tariffs, J:n t.he llrst two tables those fa.dors \vere taken into aCcollnt, at

least partially. Moreover, even the tariffs in the World Bank data set seems

too low. F'elTcira andllossi (2003) sl1mv Umt in Brazil, in Lhis period, avcrage

tarilT was doser to 100%) than 47%, the mnnber in lhe vVorld Bank database. Ir we redo t he above exercise usíng the formeI' value ínstead of the later, we find that T i8 nhle lo explain almost 30% of the TFP gap. Moreover, inslead

of onIy expIainillg 2.2%, of the output per worker difIerence with respect to

the D.S., it now explaius 5.8%. Ir t.his is a general pattern of ta1"i[[· under-measnrelnent, イ・セュャエNウ@ in Table 3 would be very diiferent.

A second possible reason for lhis resuU is Lhe fact that we were usmg

very conservative calibration, one that tends to reduce the gains from trade.

So itmight be the case that for diHcrent. values of 00. and C'Ib - particularly

those that Zャョ」イ・。ウヲセ@ Lhe difIerence heb;veen lhern - we came up wilh larger

TFP losses. This, however, is not the case unless we use very unreasonable

pararnet.er \'1:1111es. Fbr instance, wit.h 00. and n:b equal to 0.2 anel OAG7 (valnes

that still generate

("0

= 1;:3)), T would explain 4A%, 6A% anel 10.1%, of TFP difrerence of Argentina, Bangladesb anel Brazil, respedively. Those キセQオ・ウ@are very dClse to tho8e displayed on Tahle

:3.

Finally, results when nsing 2000 data. found that in almost no case the

ejTect of T i'l far from zero. In this case barriers to trade were found to bc

irreleva.nt as most conntries experienced major trade liberalization after the

mid 1980's. CHUCUUy, protection i8 focnsed in fcw, albciL key, sectors bnt this does not show up in the data among othc1' reaSOll:::l because tariH" is not

the maln illstrumcnt u:sed. This is ln accord "viU1 Hodrik (77) LhaL i-U·gllCS

that the gains from the current trade negot.iations, in tcrms of outpnt, are

probably suml1 as most cconomies a.re now relaLively OpCIl.

\Ve can also e:stiniate t-he output C08t

01"

barriers Lo trade. \Ve use thefoHowing fonnula:

In this expression, ''.Te re-estimaLe country i ouLput with tiS tarifI in pInce

of its own. It gives the measured gain

01"

output if country i had its observed factor:-; of procluction but American tariffs. The gaills, in perccntage terms,are presenLed below

Thble Li: Outpnt gains frorn "lrade" refonn

l\1íd 1960's Yin Mid 1980's I" .YIT*

Chile G.9% Costa Rica 4.:3%

13razil

5.8S1;)

Brazil 7.6%Pakistan 2.7% Ivory Coast 6.2?1()

Philippines RNQセセQ@ Thailand 3.2%

According; to Table 4, Brazil lU the eighties v!Ould be 8 percent richel'

if its eflective mte 01' protection \vere considerably smaller. Although no!'

enongh to dose t.he gap to the US OULpllt. - GDP per \vorkel' of Brazil was

one third 01 that of lhe US in Lhe perioel - this is no small mnnber. Like,vise, fig11res for Chile, Ivory Coast and Costa Rica \vere relevant. In these cases

Lhe static gain

01'

eliminaLing lmrriel's to trade would increase hy 5S'{) 01' rnore outpu1. per vlOrker. 01' course, as we could expect given 1'esults of T,'1.b1e 3, the rneasure gains nsillg World Bank dRta are smaller. For the OECDcountries-(1,8 a matter 01' fact, for a majority of countries - the estimated gains are dose

t.o zero. However, in t,hose cases ívere average tarijIs \vere relatively large,

such as Bangladesh anel Indin, their reduction to US tariff leveis would imply

gains of 5%

01'

per wOl'ker GDP.5

Conclusion

In 1.his papel' \ve presented evidence tha1. barriers to I.rade were impOl't.an1.

fador impairing lhe Pl'Odllctivity o[ less developed countries in the recent

pasto In some cases it explained a sízable parI. of TFP dífference wiLh respect

to Lhe leadillg cconomy. l\!Ioreovel', Lhe onLput cos(, ma)r also he l'elevant.

18

,

The ütd that in mauy cases Lhe cosI, of trade halTiel's were estimaLed to

he sIllall may be either an indication of data. problems, \vhich are \vell know

in the trade lield - larifr is not aIways a precise mensure of baniers to trade

- or may reHect the fact lhat protectionislll is not too hannflll nowadays. 01'

Um,t an ag,g,TegaLe model sl1ch as OUI'::; are no!' abJe Lo capture the l"nll eHed of

sophisticate protection measures v/ideIy useel today, such as export subsidy

OI' anti-duping mensures.

The methoelology we use does not capture lhe ütcl that barriers to lraele

elo afiect investment decisions anel so capital stocks, son1.ething \ve have shown

in onr previous paper Hhセャt・ゥイ。@ anel Trejos (200G)). In this sense, lhe current

exercise is limiteel as it takes stocks as given but does not consieler lhat, if

it. were noto for lrade restrictions, they would be cOllsidenl,hly la.rger. llence,

re;omlts hcre can be seen as a lower bounel of the eosts

01'

banires to lrade.References

[1] Balassa, 8.,1971. "The 8tnlct'U're of Protect.ion m DE,ve!oping

Coun-(TÚS," 'J'he Johns IJopkins Press, Baltiulore.

[2] CordeIl, \IV. , 1971. "The elTects of lrade on Lhe raLe of g,Tovv"t.hl!, in

Bhagwati, Jones, Mundell e Vanek, Trade, Bala'nc6 of Payments anti

GnJ7Dth, (NOl'Lh-HoUand), 1

17-1A:3.

[:3] FelTeim, P. G and L .. 110.'>8i Jr, 200:3. "New Evidcnce ou Trade Liberal-ization aml Produdi vily Growth," Inf:eT1wíionalBconomic Revicw 44,

1:3S:3-1A07.

Hl

Ferreira, P.c. Hnel A. Trejos ,2006. "On the Long-rnll Effects of Barriers t.o Trade." F'úrthcoming, Interrwt'ional Economic Revicw.[r.]

Gonzalez-Vega anelR.

l\iJonge, 1995. "Econonl'Ía Pol[t'Íca, Protec··. .

1

n R ' H(8

T

(1F1.· . A

·i .'H セᄋNGNHIᄋQQNQᄋBᄋLGWGLNLHᄋI@

.

u

Y. '

I, l"J' (:]'t"ll,r'(,>., , I L·· .. '" " \ j I (') " . , "ta , .. ·I·ô(l c",," < 'tIl ()"'(' , .. >', .. oct o>.c.

q.

1('",c,,

',,< ,-"tC t·" "1111" c.de Celltromnérica).

[G] Hall,H. anel C. Jones, 1999. "\Vhy Do Some Countries Proeluce

80

MuchMore Output per 'VVorker Than Others?," (JuaTtcTly Jowrnal of

Eco-ョッュゥ」ᄋセL@ 114, 8:j-11G.

[7]

Harrisj)n,A.,

1996. "Openness anel GTovvth: a Time-Series, Cross-Conlltl'y Analysis for Developing Conntries," Jolt'l'na{ of DeudopmentEconomics, ·'18, 419-L147.

[8]

Klenmv, P. J. anelA.

Roelriguez-Clare, 1997. "The neoclassical revival in gTüwLh economics: bas it gone too far?," in Ben S. Bernanke anel Julio.T. Rotemberg, eds, NBER AlacrDf:conom'Íc8 AnnLlal 19.97 (Cmnbridge, MA: 'lhe MIT Press), n-103.

[9J ldankiw, N. G., 1995. "The GrmOl,rth of Natiolls." Bmoking Paper8 on Economic Actiuity 1: RWU\セRエZ[N@

[lOJ Mankiw, N. C., Romer, D. anel D.Weil., 1992. "A ConLribution 'Ih The

Empirics

01'

Economic Grmvth." Quar'tt:rly JOIlT1wl of Ecolwlnic8 107 (May): 407-Ll:n,[lIJ Prescot L, K, H)98. :'Neeeled: a Total Facto!' Prodnctivit,Y Theory,"

In-tenwtirl1lal Economic Rt:vú:w, 39: 525-552.

20

FUNL'AÇ.\OGETUUO VARGAS

BIBLIOTECA MARIO HENRIQUE SIMONSEN

..

,

[12] Psncharopoulos, Go, 1994. "Heturns to InvestmcnL in Edncation: A

Global Update," World Devf:loprncnt, 22(9): 1325-13,j:t

[13] 'll-ejos,

Ao,

1992"On Lhe Short-Rull Dynamic Eflects of Compara tiveAd vantage 'Jj.'aete ," mmmscripL, UniversiLy of Pel1nsylvalliao

{QセQ}@ Ventura, .1, 1n970 "CrO\vth anel Interdependence", (Juo/lúTly Jonnlal of

e」ッョッュセウL@ 112, 57 -8e1.

[15] vVorld Bank HQYYセセI@

[16] vVorld

llank(2005)N.Cham. P/EPGE SA F383m Autor: Ferreira, Pedro Cavalcanti.

Título: Measuring the TFP costs of barriers to trade.

385151

1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 102443

000385151

1111111111111111111111111111111111111

FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS

BIBLIOTECA

ESTE VOLUME DEVE SER DEVOLVIDO A BIBLIOTECA NA ÚLTIMA DATA MARCADA