w w w . j c o l . o r g . b r

Journal

of

Coloproctology

Original

Article

Health

locus

of

control,

body

image

and

self-esteem

in

individuals

with

intestinal

stoma

Geraldo

Magela

Salomé

a,∗,

Joelma

Alves

de

Lima

b,

Karina

de

Cássia

Muniz

b,

Elaine

Cristina

Faria

a,

Lydia

Masako

Ferreira

caUniversidadedoValedoSapucaí(UNIVAS),PousoAlegre,MG,Brazil

bUniversidadedoValedoSapucaí(UNIVAS),ProgramaInstitucionaldeBolsasdeIniciac¸ãoCientífica(PIBIC),PousoAlegre,MG,Brazil

cUniversidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo(UNIFESP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received5December2016 Accepted10April2017 Availableonline10May2017

Keywords:

Intestinalstoma Qualityoflife Self-esteem Bodyimage Locusofcontrol

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Objective:Toevaluatethehealthlocusofcontrol,self-esteem,andbodyimageinpatients

withanintestinalstoma.

Method:Adescriptive,cross-sectional,analyticalstudyconductedatthepoleofthe

ostom-atesofthecityofPousoAlegre.ThestudywasapprovedbyResearchEthicsCommitteeof UniversidadedoValedoSapucaí.Opinion:620,459.Patients:44patientswithanintestinal stoma.Fourinstrumentswereused:aquestionnairewithdemographicandstomatologic data, the Health Locus of Control Scale, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale/UNIFESP-EPM,andtheBodyInvestmentScale.Statistics:Chi-square,Pearson,Mann–Whitneyand Kruskal–Wallistests.p<0.05wasdetermined.

Results:Themajorityofpatientswereover70years,16(36.4%)werefemale,30(68.2%)were

married,31(70.5%)wereretirees,31(70.5%)hadanincomeof1–3minimumwages,32(72.7%) didnotpracticephysicalactivity,18(40.9%)hadanincompleteelementaryeducation,and 35(79.5%)participatedinasupportorassociationgroup.33(75%)participantsreceivedthe stomabecauseofaneoplasia;and33(75%)hadadefinitivestoma.In36(81.8%)participants, thetypeofstomausedwasacolostomy,and22(50%)measured20–40mmindiameter;32 (72.7%)participantsusedatwo-piecedevice.Withregardtocomplications,therewere29 (65.9%)casesofdermatitis.ThemeantotalscorefortheHealthLocusofControlScalewas 62.84;fortheRosenbergSelf-EsteemScale,27.66;andfortheBodyInvestmentScale,39.48. Themeanscoresforthedimensionsinternal,powerfulothers,andchanceoftheHealth LocusofControlScalewere22.68,20.68,and19.50,respectively.WithrespecttotheBody InvestmentScale,forthedimensionsbodyimage,bodycare,andbodytouch,themean scoreswere11.64,11.00,and13.09,respectively.

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:geraldoreiki@hotmail.com(G.M.Salomé). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcol.2017.04.003

Conclusion: Inthisstudy,theparticipantsshowedchangesinself-esteemandbodyimage andalsoshowednegativefeelingsabouttheirbody.Ostomizedindividualsbelievethatthey themselvescontroltheirstateofhealthanddonotbelievethatotherpersonsorentities (physician,nurse,friends,family,god,etc.)canassistthemintheirimprovementorcure and,inaddition,believethattheirhealthiscontrolledbychance,withoutpersonalorother people’sinterference.

©2017SociedadeBrasileiradeColoproctologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisis anopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Lócus

de

controle

em

saúde,

imagem

corporal

e

autoestima

nos

indivíduos

com

estoma

intestinal

Palavras-chave:

Estomaintestinal Qualidadedevida Autoestima Imagemcorporal Lócusdecontrole

r

e

s

u

m

o

Objetivo:Avaliarolócusdecontroledasaúde,autoestimaeimagemcorporalemportadores

deestomaintestinal.

Método: Estudo descritivo,transversal, analítico; realizadono Polo de ostomizadosda

cidadedePousoAlegre,aprovadopeloCEPdaUniversidadedoValedoSapucaí.Parecer: 620.459.Casuística:44pacientescomestomaintestinal.Foramutilizadosquatro instru-mentos:questionáriocomdadosdemográficoserelacionadosaoestoma,EscaladeLócus deControledaSaúde,EscaladeAutoestimadeRosenberg/UNIFESP–EPMeBodyInvestment

Scale. Estatística:TestesdoQui-quadrado, Pearson,Mann-Whitneye deKruskal-Wallis.

Determinou-sep<0,05.

Resultados: Amaioriatinhaidadeacimade70anos,16(36,4%)eramdogênerofeminino,

30(68,2%)eramcasados,31(70,5%)aposentados,31(70,5%)tinhamrendade1a3salários mínimos,32(72,7%)nãopraticavamatividadefísica,18(40,9%)nãocompletaramoensino fundamentale35(79,5%)participavamdegrupodeapoioouassociac¸ão.33(75%)dascausas daconfecc¸ãodoestomaforamporneoplasiaeem33(75%)oestomaeradefinitivo.Em36 (81,8%)oestomaeradotipocolostomia,22(50%)mediamde20a40mmdediâmetroe 32(72,7%)eramdispositivosduaspec¸as.Comrelac¸ãoàscomplicac¸ões,29(65,9%)foram dermatite.AmédiadoescoretotaldaEscalaparaLocusdeControledaSaúdefoide62,84; EscaladeAutoestimadeRosenberg,27,66;eBodyInvestmentScale,39,48.Comrelac¸ãoàmédia doescoretotaldasdimensõesdaEscalaparaLocusdeControledaSaúde,constatamos: Internalidadeparasaúde,22,68;Externalidade“outrospoderosos”,20,68;eExternalidade parasaúde,19,50.Comrelac¸ãoàsdimensõesdaBodyInvestmentScale,constatamos:para Imagemcorporal,médiade11,64;Cuidadocorporal,médiade11,00;eToquecorporal,média de13,09.

Conclusão: Osparticipantesdoestudoapresentaramautoestimaeimagemcorporal

alter-adasesentimentosnegativosemrelac¸ãoaocorpo.Osostomizadosacreditamqueeles próprioscontrolamoseuestadodesaúdeenãoacreditamqueoutraspessoasouentidades (médico,enfermeiro,amigos,familiares,Deus,etc.)possamajuda-losemsuamelhoraou curaequesuasaúdeécontroladaaoacaso,seminterferênciaprópriaoudeoutraspessoas. ©2017SociedadeBrasileiradeColoproctologia.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

OstomycomesfromtheGreekwordstoma,meaning open-ingorbuildinganewmouthofsurgicalorigin,whichismade whenthereisaneedtomakeatemporaryorapermanent diversion from the normal transit of food or elimination. Consideringthe typesofostomy,the intestinal typeisthe mostfrequent.Thistypeischaracterizedbythe exterioriza-tionofthecolonthroughtheabdominalwall,withthegoal offecalelimination;ontheotherhand,theartificialopening

whichisdefinedastheimagethateveryhumanbeing con-structsofhis/herownbodythroughoutthelife,andthatkeeps upwithtohis/herneedsandtotheenvironmentinwhichthis humanbeingisliving.3

When experienced by the ostomized person, sexuality manifests itself through negative feelings: worry, anguish, fear, shame, isolation, inferiority, and control of his/her desires. Thereports show that ostomized persons refer to theirbodyasnotbeingthe sameasbefore,andbetraythe changesintheirsexualactivitiesduetophysicaldiscomfort, embarrassment,andthesideeffectsoftheadjuvanttherapy.4 Inadditiontofacingchangesinself-image,changesin sex-ualactivity,andsocialandfamilyisolation,ostomizedpersons mustconfrontotherconcerns:complicationsthatmayoccur withthestoma,especiallyproblemsoflossofskinintegrity aroundthestoma,changesintheireliminationpattern,the factthatthepersonbeginstoevacuatethroughtheabdomen, frequentoccurrenceofleakageofsecretionaroundthebag, presenceofodorandeliminationofgases;changesineating habits;andtheneedofperistomalskin-relatedhygiene(i.e., self-care).5,6Itisoftencriticaltheunderstandingandsupport fromfamilyandfriends,andespeciallyfromtheprofessional whoshouldguidethepatientandhis/herfamilywithregard toself-care,thatis,thecareandhygieneoftheperistomal skin,suchaschangingthebag,etc.Inshort,thisisaperiod ofdifficultadaptationfortheostomized personinhisnew life.7–10

The adaptation process occurs with the adjustment of a whole life and in a new context, in which, in many cases,importantfactorsneedtobeabandoned,replaced,or reduced.11 Thus,thisisanindividualprocessthatdevelops overtimeandinvolvesaseriesofaspects,rangingfromthe helpoffered,tothewaytheostomizedpersongetsinvolvedin self-care.11

Asalreadynoted,thelackofhealthcontrolandthe diffi-cultytoperformself-carefortheadaptationtothisnewlife aresomeofthemajorproblemsforostomizedpersonsandfor theirsocialization,andthisprocessmaytakeseveralmonths. Sociocultural,psychologicalandemotionalaspectsarerelated tothese difficulties and tothe lack ofcontrol. TheHealth LocusofControl,beliefs andpsychological, emotional,and socialchangesareimportantaspectsofdoingself-careand fortheindividual’sadaptationtohis/hernewwayoflifeand socialization.

Locusofcontrolisamodelthatproposesthatthe individ-ual’sbelief(internalandexternalmotivation)determinesthe actiontobetaken.Thosewhobelievethattheresults,atleast inpart,aredependentontheactionstaken,areconsidered tobeinternallyoriented.Thosewhohaveexternalguidance generallydonotbelieve,orhavelittlefaith,intherelationship betweenoutcomeandindividualaction.12

Autonomyandindependencearegoodindicatorsforthe healthoftheostomizedperson,sincethe inabilityto inter-veneinitscontextcanbringupasenseoffailure.Thus,ifthe individualascribehis/herfailuretopersonaldeficienciesina generalizedandlastingway,he/shemaypresentwithafeeling ofineffectiveness.13,14

Thegreaterthesenseofpersonalcontrolandtheabilityto commandandmakedecisions,themoreintensewillbethe feelingofsatisfaction.Self-esteemandself-imagealsodepend

not onlyon the individual,but onhis/herinteraction with othersandwithsociety.15–19

Healthprofessionalsarefittedwithtechnicalandhuman skillsthatenablethemtoprovidehelptoostomizedpersons, who, intheir daily lives, return tothe outpatient clinicto continue theirtreatment. In many cases,these individuals arrive atthe outpatientclinicwithanxietyand frustration, notacceptingself-care,andwithoutaperspectiveofcure;in addition,theyexpressfeelingsofloss.Thus,inthesepatients, theevaluationofself-esteemandself-imagecanresultin sub-sidies,sothattheircareisimprovedandmoreappropriately directedtotheindividualneedsoftheostomizedperson.

Objective

Toevaluatethehealthlocusofcontrol,bodyimage,and self-esteeminpatientswithanintestinalstoma.

Method

This isa descriptive, cross-sectional, analytical study.This studywasconductedatthePoleofostomizedpatientsinthe city ofPouso Alegre, afterapproval bythe Research Ethics CommitteeoftheUniversidadedoValedoSapucai(opinion number:620.459). Forty-four patientswithintestinalstoma participatedinthe study.Thedatawerecollected afterthe signingofthe FreeInformedConsentForm bythe patient, or byhis/heraccompanyingperson.Data werecollectedby theresearchersthemselves.Thequestionswereaskedduring theinterview.Thesamplewasselectedinanon-probabilistic manner,forconvenience.Theinclusioncriteriaforthisstudy were: age ≥18 years and presence of an intestinal stoma.

Thecriteriafornon-inclusionwere:patientswithadementia syndrome and/orother conditions thathamper the under-standingandresponseofthequestionnaires.

Four datacollectioninstruments wereused: a question-naire on socio-demographic and stoma-related data, the Health LocusofControlScale, theRosenberg/UNIFESP-EPM Self-esteem Scale,and finally the Body Investment Scale.8 Theinterviewslastedapproximately20minandthedata col-lection onlystartedafterthe approvalfrom the Ethics and ResearchCommitteeoftheFaculdadedeCiênciasdaSaúde “Dr.JoséAntônioGarciaCoutinho.”

(items2,4, 9,11,15,and 16),in whichthe scoresindicate towhatdegreethepersonbelievesthathisorherhealthis controlledbychance,without interferencefromhimself or fromothers.Thescoresforeachdimensionrangefrom1to 5,withthe followingscores:for“Itotallyagree,”+5;“I par-tiallyagree,”+4;“Iamundecided,”+3;“Ipartiallydisagree,” +2;and“Istronglydisagree,”+1.Thescoreobtainedforeach dimensionwillbethesumoftheitemsinthesubscalein ques-tion.Thesumofthevaluesofthe itemsbelongingtoeach ofthethreesubscalesrepresentsthetotalscoreinrelation tothelocusofhealthdimensioninquestion.Thetotalvalue obtainedforeach subscalecan varybetween6and 30and indicatesthatthelargerthe value,the greaterthebelief in thisdimension.Thescaleispresentedasunique,wherethe subscaleitemsintersect.20

TheRosenberg-EPM Self-EsteemScalewas translatedby Dini21intothePortugueselanguage,withmeasurement prop-erties such as reproducibility, validity and responsiveness. Thisscaleisaspecificinstrumentwithpsychometric prop-ertiesonlyforasinglecharacteristic,self-esteem.Thescale consistsoften statements, which may represent disagree-ment or agreement, in whichthe person hasfour choices ofresponse rangingfrom “I fully agree”to “I strongly dis-agree”.Initems 1,3,4,7and 10,the option“I fullyagree” referstothehighestself-esteem,andinitems2,5,6,8and9, thisoptionpointstothelowestself-esteem.Foreach alterna-tive,thepatientexaminedshouldindicateonlyoneresponse, accordingtowhathe/sheisfeelingatthemomentofthetest. Eachresponsealternativereceivesascorerangingfrom0to 3,and these points,over the 10 questions,must beadded togetherandrepresentthefinalscoreobtainedfromthe ques-tionnaire.Thequestionnairescoresrangefrom0to30,with 0 being the best result, and 30 being the worst state for self-esteem.21

TheBrazilianversionoftheBodyInvestmentScaleconsists of20items,dividedintothreefactors(bodyimage,bodycare, andbodytouch).Theresponsesarearrangedinafive-point Likertscale,from“Itotally disagree”(1point)to“I strongly agree”(5points).Inordertoobtainthefinalscoreofthisscale, thescoresofitems2,5,9,11,13and 17must beinverted, andthen,allitemsareaddedup.Thehigherthescore,the greaterwillbethepositivefeelinginrelationtothebody.The dataobtainedweresubmittedtoanExploratoryFactor Anal-ysis,withVarimaxrotation.IntheBrazilianscale,ofthe24 originalitems,20weremaintained,and4factorsexplained 36.3% ofthe totalvariance ofthe scale.For factor 1(Body Image),a=0.81;forfactor2(BodyCare),a=0.70;andforfactor 3(BodyTouch),therewasinternalconsistencyata=0.66.For thefourthandlastfactor(BodyProtection),a=0.37.22

In the evaluation of the results, the data were entered and analyzed by the statistical program SPSS-8.0. For the analysisofthefindings,the followingstatistical testswere applied: Pearson’s Chi-squared test for the distribution of absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies (this test deter-minedwhetherthedistributionwasdifferentfrom5%,that is, p≤0.05); Mann–Whitney test for comparison between

twogroups;Kruskal–Wallistestwhenthereweremorethan two groups; and finally, the Spearman correlation for the correlation of continuous variables with semi-continuous variables.

Results

Table 1 shows that the majority of the study participants

were women,withageover70years,married,retired,with anincomeof1–3minimumwages,didnotpracticephysical activity,andhadanincompleteelementaryeducation.Only 35(79.5%)patientswereengagedinasupportorassociation group.Significancewasnotedinallvariables.

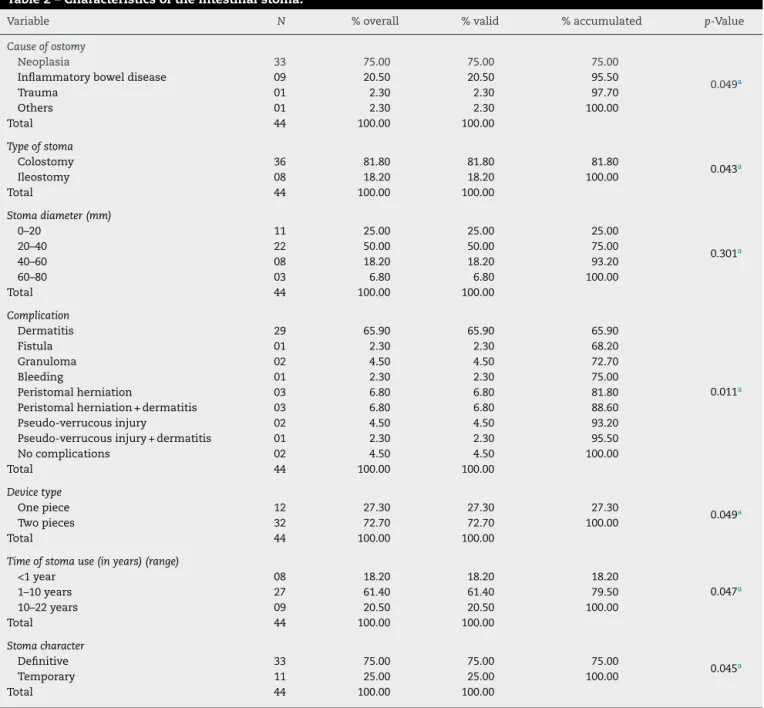

Table2shows that,forthe mostpart, colostomieswere

definitive,duetoneoplasia,with20–40mmindiameter,and with2-piecedevices.Themostfrequentcomplicationwas der-matitis.

Table3presentsthemeanofthetotalscoreforthescales applied:HealthLocusofControlScale,62.84;Rosenberg Self-esteemScale,27.66;andBodyInvestmentScale,39.48.These meanssuggestthattheostomizedpatientswhoparticipated inthe studyexhibitedaltered self-esteemandbody image, that is,theseindividuals presentednegativefeelingsabout theirbody;however,theybelievedthattheycouldcontroltheir healthandthat,moreover,thepeopleinvolvedintheircare andrehabilitationcouldnotcontributetotheirimprovement. There wasnostatisticalsignificanceinthe variable“stoma diameter.”

Table4liststhemeanoftotalscoreofthedimensionsof theHealthLocusofControlScale:InternalHLC, 22.68; Pow-erfulothersHLC,20.68;andChanceHLC,19.50.Theseresults demonstratethatourpatientsbelieved thattheycontrolled themselvestheir health,and thattheydidnotbelievethat other people orentities(doctor, nurse,friends,family,god, etc.)couldhelpthem,andthattheirhealthiscontrolledby chance,withoutinterferencefrom themselvesorfrom oth-ers.WithrespecttothedimensionsoftheBodyInvestment Scale,thefollowingmeanswereobtained:bodyimage,11.64; bodycare,11.00;andbodytouch,13.09.Therewasstatistical significanceinallvariables.

Discussion

Inthe21stcentury,chronichealthconditionshavebecome particularlyimportantinhealthcareservicesinBrazil;this newsituationincreasesthelifeexpectancyofBrazilians,who arethenexposedtohealthproblems,suchascancer,trauma, and chronic degenerative diseases. Many people undergo surgery to makethe stoma, with a view to providing the patientwithabetterqualityoflife.4

Table1–Sociodemographiccharacteristicsofindividualswithanintestinalstoma.

Variable N %overall %valid %accumulated p-Value

Gender

Male 18 40.90 40.90 40.90 0.039a

Female 26 59.10 59.10 100.00

Total 44 100.00 100.00

Agegroup

38–49years 11 25.00 25.00 25.00

0.455a

50–59years 06 13.60 13.60 38.60

60–69years 11 25.00 25.00 63.60

70–87years 16 36.40 36.40 100.00

Total 44 100.00 100.00

Maritalstatus

Married 30 68.20 68.20 68.20

0.041a

Single 06 13.60 13.60 81.80

Widowed 08 18.20 18.20 100.00

Total 44 100.00 100.00

Occupation

Retired–“r” 31 70.50 70.50 70.50

0.049a

Unemployed–“u” 05 11.40 11.40 81.80

Working–“w” 08 18.20 18.20 100.00

Total 44 100.00 100.00

Supportgroup

Yes 35 79.50 79.50 79.50

0.037a

No 09 20.50 20.50 100.00

Total 44 100.00 100.00

Income

<1minimumwage 02 4.50 4.50 04.50

0.048a

1–3minimumwages 31 70.50 70.50 75.00

3–4minimumwages 10 22.70 22.70 97.70

≥5minimumwages 01 2.30 2.30 100.00

Total 44 100.00 100.00

Practicesphysicalactivity

Yes 12 27.30 27.30 27.30

0.043a

No 32 72.70 72.70 100.00

Total 44 100.00 100.00

Education

Incompleteelementaryeducation 18 40.90 40.90 40.90

0.076a

Completeelementaryeducation 07 15.90 15.90 15.90 Canreadandwrite 19 43.20 43.20

Total 44 100.00 100.00 100.00

a Statisticalsignificance;Pearson’sChi-squaredtest(p≤0.05).

Inthisstudy,weverifiedthatthemajorityofthe partici-pantswerewomen,agedover70years,married,retired,with anincomeof1–3minimumwages,didnotpracticephysical activity,andhadanincompleteelementaryeducation.Only35 (79.5%)oftheindividualsstudiedwereengagedinasupport orassociationgroup.Suchdataarecompatiblewithseveral studiespreviouslypublished.23–26

Itis importantto note that the elderly exhibit peculiar biologicalcharacteristicsandaremorevulnerableto chronic-degenerativediseases,forexample,neoplasia.Meirellesand Ferraz(2001)statethattheoccurrenceofcomplicationsinthe stomahasamultifactorialcharacter,involvingfromthe con-fectionofthestoma,itslocation,totheobesityofthepatient, withaninfluenceoftheagefactor.Thus,whensuchfactors areassociatedwiththephysiologicalalterationsofaging,the

elderlyareingreatervulnerabilityregardingtheincidenceof complicationsinthestoma.27,28

Women tendto take less time to rehabilitate,although showingsignificantdegreesofdespair,depression,andfear inthepreoperativeperiod.Men,especiallythosewhodevelop sexualimpotence,takealongertimetorespond satisfacto-rilytotheirroutineactivities,includinggreaterdifficultyfor self-care.24

Table2–Characteristicsoftheintestinalstoma.

Variable N %overall %valid %accumulated p-Value

Causeofostomy

Neoplasia 33 75.00 75.00 75.00

0.049a

Inflammatoryboweldisease 09 20.50 20.50 95.50

Trauma 01 2.30 2.30 97.70

Others 01 2.30 2.30 100.00

Total 44 100.00 100.00

Typeofstoma

Colostomy 36 81.80 81.80 81.80

0.043a

Ileostomy 08 18.20 18.20 100.00

Total 44 100.00 100.00

Stomadiameter(mm)

0–20 11 25.00 25.00 25.00

0.301a

20–40 22 50.00 50.00 75.00

40–60 08 18.20 18.20 93.20

60–80 03 6.80 6.80 100.00

Total 44 100.00 100.00

Complication

Dermatitis 29 65.90 65.90 65.90

0.011a

Fistula 01 2.30 2.30 68.20

Granuloma 02 4.50 4.50 72.70

Bleeding 01 2.30 2.30 75.00

Peristomalherniation 03 6.80 6.80 81.80

Peristomalherniation+dermatitis 03 6.80 6.80 88.60

Pseudo-verrucousinjury 02 4.50 4.50 93.20

Pseudo-verrucousinjury+dermatitis 01 2.30 2.30 95.50

Nocomplications 02 4.50 4.50 100.00

Total 44 100.00 100.00

Devicetype

Onepiece 12 27.30 27.30 27.30

0.049a

Twopieces 32 72.70 72.70 100.00

Total 44 100.00 100.00

Timeofstomause(inyears)(range)

<1year 08 18.20 18.20 18.20

0.047a

1–10years 27 61.40 61.40 79.50

10–22years 09 20.50 20.50 100.00

Total 44 100.00 100.00

Stomacharacter

Definitive 33 75.00 75.00 75.00

0.045a

Temporary 11 25.00 25.00 100.00

Total 44 100.00 100.00

a Statisticalsignificance;Pearson’sChi-squaredtest(p≤0.05).

Table3–Resultsobtainedformeantotalscoresofthe HealthLocusofControlScale,RosenbergSelf-esteem Scale,andBodyInvestmentScaleinindividualswithan intestinalstoma.

Descriptivelevel HealthLocusof ControlScale

Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale

Body Investment Scale

Mean 62.84 27.66 39.48

Median 63.00 29.00 38.00

Standarddeviation 8.061 3.791 5.928

Minimum 45 19 27

Maximum 81 40 51

p-Value 0.038a 0.049a 0.045a

Mann–Whitneytest. a p≤0.05.

haverecentlyreceivedastomawhentheydonothaveafixed partner,becausetheyfeelinsecureandembarrassedforfear ofnotbeingacceptedbythepartner.

It is important that family members, caregivers, and professionalsprovide emotionalandpsychologicalsupport, becausewhentheostomizedpersonreceivesastoma,he/she becomesrestrainedinhis/hersexual,leisure,socialand pro-fessional life. The ostomized individual begins to see the ostomyasananatomicalmutilation.Inthisway,family mem-bers,caregiversandprofessionalsbecomeessentialpartsof theelaborationofatherapeutic,rehabilitation,andsocial rein-tegrationplan.

Table4–ResultsobtainedformeanscoresofHealthLocusofControlScale,RosenbergSelf-esteemScale,andBody InvestmentScaledimensionsinindividualswithanintestinalstoma.

Mean Median Standarddeviation Minimum Maximum p-Value

HealthLocusofControlScale

InternalHLC 22.68 23.00 2.466 16 28 0.038a

PowerfulothersHLC 20.68 20.00 4.208 12 29 0.027a

ChanceHLC 19.50 20.00 4.995 10 30 0.035a

BodyInvestmentScale

Bodyimage 11.64 11.00 1.753 10 16 0.021a

Bodycare 15.00 13.50 4.666 10 28 0.019a

Bodytouch 13.09 12.0 2.868 10 19 0.020a

Kruskal–Wallistest. a p≤0.05.

andpatientshadbeenlivingwiththestomafor1to10years. Theseresultsagreewithseveralnationalandinternational studies.23–26

RegardingtheBodyInvestmentScaleand theRosenberg Self-EsteemScale,weobservedachangeinthescore, indi-catingthat theostomized patientswho participatedinthe studyhadlowself-esteemandlowself-image,thatis,these individualshadnegativefeelingsabouttheirbody.

Thelossperceived bythe person immediately afterthe confectionoftheostomyisthelossofthephysiologicaland anatomicalfunctionofdefecating.Withthis,theostomized individualisapersonwhowillnotsitinatoilet,becausehe mustdiscreetlypourhis/herstoolandlivewithanartificial anus overwhich he/shenomorehas anycontrol. Because ofthisexperience,ostomizedpatientsfacefeelingsof frus-tration,uselessness,mutilation,andself-rejection,aswellas moodswingsand,especially,difficultiesinself-careandinthe adaptationtothisnewwayoflife.Thisresultsinchangesin self-esteemandbodyimage.29

In studies investigating the quality of life and self-esteem in patients with an intestinal stoma, the means ofRosenberg/UNIFESP-EPMSelf-EsteemScaleand of Flana-gan Quality of Life Scale (FQVS) were 10.81 and 26.16, respectively.16

Anotherstudy inwhichthe sociodemographicand clin-icalfactors were evaluated, itsparticipants had amean of 10.81ontheRosenberg/UNIFESP-EPMSelf-EsteemScale.For theBodyInvestmentScale,atotalscoreof38.79wasobtained, and the means for the Body Image and Personal Touch domainswere,respectively, 7.74and 21.31.When we com-paredthe stomaandsociodemographic-relateddataversus theRosenberg/UNIFESP-EPMSelf-EsteemScaleandtheBody InvestmentScale,wenoticedthatallpatientsshoweddeclines inself-esteemand self-image.Thosepatientsnotinformed thattheywouldreceiveastomaandinwhichthedemarcation wasnotperformed,presentedaworseninginself-esteemand self-image,inrelationtootherlesionand sociodemographic-relatedcharacteristics.Thepatientswhoparticipatedinthis studypresenteddeclinesinself-imageandself-esteeminall thecharacteristicsofthestomaandalsoinsociodemographic data;thismeansthattheseindividualshadnegativefeelings abouttheirownbodies.8

Ostomized individuals need toadapt their lifestyle and alsoincorporatetherapeuticpracticesthat involvechanges

ineatingpatterns,hygiene,thepracticeofphysicalactivities, self-care(includingtheexchangeofthebagandperistomal skin hygiene), and acontinuous monitoringby a multidis-ciplinary health team. Coexistence with a stoma implies adjusting oneself to the complex dynamics between fam-ilyrelationships,personalfeelings,lifestyle,andchangesin habits, routines’adequacy, andtheimplementation ofcare relatedtothepreventionofcomplications. Thewaypeople perceivetheirconditioninfluencestheoverallcontroloftheir stateofhealth-illness,psycho-emotionalaspect,sincemany ofthesepeopledonotbelievethattheyareabletocontroltheir healththroughself-care anddailyactivitiesandthat those peopleinvolvedintheircareandrehabilitationcannot con-tributetotheirimprovement.Withthatinmind,manyofthese patientsendupisolatingthemselvesfromsociety,familyand leisure–inshort,thesearepeoplewhopresentthemselves withimpairedqualityoflife,well-being,self-esteem,and self-image.8,16,30,31

Instudiesthatevaluatedsubjectivewell-beingand qual-ity of lifeinpatients with anintestinal stoma,the results ofthe FlanaganQualityofLife Scale rangedfrom 16to 22 points,indicatingthatthesepatientshadtheirqualityoflife altered.Regardingthesubjectivewell-beingscaleinthethree domains: Positive affect – 43 (61.40%) individuals;Negative affect–31(44.30%)individuals,andSatisfactionwithlife–54 (77.10%)individuals,allparticipantsscored3points, charac-terizinganegativechangeinthesedomains.Themeanofthe FlanaganQualityofLifeScalewas26.16,andthemeansofthe SubjectiveWell-beingScaledomainswereasfollows:Positive affect,2.51;Negativeaffect,2.23;and Satisfactionwithlife, 2.77,suggestingthatinthisstudy,participantswithintestinal stomapresentednegativefeelingsrelatedtoself-esteem,and tothelossintheirqualityoflife.32

WiththeapplicationoftheHealthLocusofControlScale, theseresultsdemonstratedthatostomizedpeoplebelievethat they controlthemselvestheirhealth, and thattheydonot believethat otherpeople orentities(doctor, nurse,friends, family, god,etc.)couldhelp them,and thattheir healthis controlledbychance,withoutinterferencefromthemselves orfromothers.

the effects caused byhis/her perceptionin relationto the controlofperformances,competencies,andabilities: those individualswhoattributetheirsuccesstopersonaleffortsand personalattributestendtodevelopmorepositiveaffectsand betterperformanceexpectations;ontheotherhand, individ-uals who attribute their failuresto anunfitness orlack of abilityoften feel anxious,guilty, and fearful; and,in addi-tion,they have less efficiency. Three areas are affected by theperceivedcontrol:behavior,cognitiveabilities,and affec-tiveexpressions.Withinthissameline,otherstudiesrelate the consensusofself-efficacyto learningand tothe moti-vationnecessary to achieve successin learning,indicating thatlearningdifficultiesariseinassociationwithalowsense ofself-efficacy,low motivation,unfitness toperformtasks, inabilityoforganization,and “maladaptive”behavior.12,33–36 Suchvariablesarenecessaryfortheadaptationtothenewway oflifeofostomizedindividualsandforperformingself-care.

The adaptive process occurs with the adjustment of a wholelife,inanewcontext,inwhichimportantfactorsoften haveto beabandoned, replaced or shortened.28 Therefore, this is an individual process that develops over time and whichinvolvesaseriesofaspects,rangingfromtheassistance offeredtothewaytheostomizedpersonengagesinself-care. Topreventthisfromoccurring,themultiprofessionalteam shouldprovideglobalassistance,addressingbiopsychosocial andemotionalneedsinordertoimprovethepatient’sliving condition.Infaceofthesefacts,weconsiderthatthecare, con-cerns,andeventhedevelopmentofinterpersonalrelationship arenotlimitedtopsychiatry,but theseaspectspertainalso toany areawhereaneedforhumancareispresent.Thus, theserelationshipsmustoccurinsuchawaythatemotional, economicandculturalaspectsaretakenintoaccount,where dialogisaprimaryfactor,inanefforttoachievetheintegral healthoftheindividual.Whentheprofessionalrealizesthese feelings,will beable toimplementthe care, reviewingthe treatment,thetypeofdeviceused,andthebag,andeventually referringthepatienttoanotherspecialist.

Conclusion

Withtheaccomplishmentofthisstudy,wecanconcludethat theostomizedparticipantshadalteredself-esteemand self-imageandnegativefeelingsregardingtheirbody.Ostomized peoplebelievethattheycontrolthemselvestheirhealth,do notbelieve that other persons or entities (doctors, nurses, friends,relatives,god,etc.)canhelpthemintheir improve-mentorcureandthattheirhealthiscontrolledbychance, withoutpersonalorotherpeople’sinterference.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1. RevelesAG,TakahashiRT.Educac¸ãoemsaúdeaoostomizado: umestudobibliométrico.RevEscEnfermUSP.2007;41:245–50.

2.BellatoR,PereiraWR,MaruyamaSAT,CastrodeOliveiraP.A convergênciacuidado-educac¸ão-politicidade:umdesafioa serenfrentadopelosprofissionaisnagarantiaaosdireitosà saúdedaspessoasportadorasdeestomias.RevTexto Contexto-Enferm.2006;15:334–42.

3.AlmeidaRLM,MeirelesVC,SalimenaAMO,MeloCSC.

CompreendendoossentimentosdaPessoacomColostomia.

RevEstima.2006;4:26–32.

4.BatistaMRFF,RochaFCV,SilvaDMG,SilvaJ,FernandoJG. Autoimagemdeclientescomcolostomiaemrelac¸ãoàbolsa coletora.RevBrasEnferm.2011;64:1043–7.

5.MartinsPAF,AlvimNAT.Perspectivaeducativadocuidadode enfermagemsobreamanutenc¸ãodaestomiadeeliminac¸ão. RevBrasEnferm.2011;64:322–7.

6.NascimentoCMS,TrindadeGLB,LuzMHBA,SantiagoRF. Vivênciadopacienteestomizado:umacontribuic¸ãoparaa assistênciadeenfermagem.RevTextoContexto-Enferm. 2011;20:557–64.

7.SaloméGM,CarvalhoMRF,MassahudJuniorMR,MendesB. ProfileofostomypatientsresidinginPousoAlegrecity.J Coloproctol.2015;35:106–12.

8.SaloméGM,AlmeidaSA.Associationofsociodemographic andclinicalfactorswiththeself-imageandself-esteemof individualswithintestinalstoma.JColoproctol.

2014;34:159–66.

9.CarvalhoSORM,BudóMLD,SilvaMM,AlbertiGF,SimonBS. “Comumpoucodecuidadoagentevaiemfrente”vivências depessoascomestomia.RevTextoContexto-Enferm. 2015;24:279–87.

10.MauricioV,SouzaNVDO,LisboaMTL.Osentidodotrabalho paraoserestomizado.RevTextoContexto-Enferm. 2014;23:656–64.

11.MenezesAPS,QuintanaJFA.Percepc¸ãodoindivíduo estomizadoquantoàsuasituac¸ão.RevBrasPromSaúde. 2008;21:13–8.

12.DelaColetaMF.Escalamultidimensionaldelocusdecontrole deLevenson.ArqBrasPsicol.1987;39:79–97.

13.RotterJ.Generalizedexpectanciesforinternalversusextenal controlofreinforcement.PsycholMonogr.1966;80:1–28. 14.SalgadoPCB,SouzaEAP.Variáveispsicológicasenvolvidasna

qualidadedevidadeportadoresdeepilepsia.EstudPsicol. 2003;8:165–8.

15.SaloméGM,AlmeidaSA,MendesB,CarvalhoMRF,Massahud

JuniorMR.Assessmentofsubjectivewell-beingandqualityof lifeinpatientswithintestinalstoma.JColoproctol.

2015;35:168–74.

16.SaloméGM,AlmeidaSA,SilveiraMM.Qualityoflifeand self-esteemofpatientswithintestinalstoma.JColoproctol. 2014;34:231–9.

17.SaloméGM,AlmeidaAS,FerreiraLM.Associationof sociodemographicfactorswithhopeforcure,religiosity,and spiritualityinpatientswithvenousulcers.AdvSkinWound Care.2015;28:76–82.

18.PereiraMTJ,SaloméGM,OpenheimerDG,EspósitoVHC, AlmeidaS,FerreiraLM.Feelingsofpowerlessnessinpatients withdiabeticfootulcers.Wounds.2014;26:172–7.

19.AlvesSG,ReisBC,GardonaRGB,VilelaLHR,SaloméGM. Associac¸ãodosfatoressociodemográficosedalesão relacionadoaosSentimentosdeimpotênciaeEsperanc¸aem indivíduoscomúlceravenosa.RevBrasCirPlást.

2013;28:672–80.

20.Rodríguez-RoseroJE,FerrianiMGC,DelaColetaMF.Escalade locusdecontroledasaúde–MHLC:estudosdevalidac¸ão. Latino-amEnfermagem.2002;10:179–84.

21.DiniGM,QuaresmaMR,FerreiraLM.Adaptac¸ãoculturale validac¸ãodaversãoBrasileiradaEscaladeAuto-estima Rosenberg.RevSocBrasCirPlast.2004;19:41–52.

thecommunityinstrument.JWoundOstomyContNurse. 2007;34:671–7.

23.KnowlesSR,WilsonJ,WilkinsonAM.Psychologicalwell-being andqualityoflifeincrohn’sdiseasepatientswithanostomy: apreliminaryinvestigation.JWoundOstomyContNurs. 2013;40:623–9.

24.PereiraAPS,CesarinoCB,MartinsMRI,PintoMH,Gomes NetinhoJ.Associac¸ãodosfatoressociodemográficose clínicosàqualidadedevidadosestomizados.Latino-Am Enfermagem.2012;20:93–100.

25.PaulaMAB,TakahashiRF,PaulaPR.Ossignificadosda sexualidadeparaapessoacomestomaintestinaldefinitivo. RevBrasColoproctol.2009;29:77–82.

26.SilvaAC,SilvaGNS,CunhaRR.Caracterizac¸ãodepessoas

estomizadasatendidasemconsultadeenfermagemdo

servic¸odeestomaterapiadomunicípiodebelém-PA.Rev Estima.2012;10:12–9.

27.MacedoMS,NogueiraLT,LuzMHBA.Perfildosestomizados atendidosemhospitaldereferênciaemTeresina.RevEstima. 2005;3:25–8.

28.CostaVF,AlvesSG,EufrásioC,SalomeGM,FerreiraLM.Body imageandsubjectivewell-beinginostomistsinBrazil. GastrointestNurs.2014;12:37–47.

29.MeirellesCA,FerrazCA.Avaliac¸ãodaqualidadedoprocesso dedemarcac¸ãodoestomaintestinaledasintercorrências tardiasempacientesostomizados.RevLatino-am Enfermagem.2001;9:32–8.

30.ZilbersteinB,RodriguesJG,Habr-GamaA,SaadWA,Machado MCC,CecconelloI,etal.Cuidadospréepós-operatóriosem cirurgiadigestivaecoloproctológica.SãoPaulo:Roca;2001.p. 104.

31.SaloméGM,SantosLF,CabeceiraHS,PanzaAMM,PaulaMAB. Knowledgeofundergraduatenursingcourseteachersonthe preventionandcareofperistomalskin.JColoproctol. 2014;34:224–30.

32.SalomeGM,AlmeidaSA,MendesB,CarvalhoMRF,Massahud

JuniorMR.Avaliac¸ãodoBem-estarsubjetivoedaqualidade devidanospacientescomestomaintestinal.JColoproctol. 2015;35:168–74.

33.OliveiraG,MaritanCVC,MantovanelliC,RamalheiroGR, GavilhiaTCA,PaulaAAD.Impactodelaostomía:sentimientos yhabilidadesdesarrolladasfrentealanuevacondiciónde vida.RevEstima.2010;8:19–25.

34.FernandesSCS,AlmeidaSSM.Estudocorrelacionalentre lócusdecontroleevaloreshumanos.RevInterac¸ãoem Psicologia.2008;12:215–22.

35.SaloméGM,deAlmeidaAS,deJesusPT,MassahudMRJ,de OliveiraMCN,deBritoMJA,etal.Theimpactofvenousleg ulcersonbodyimageandself-esteem.AdvSkinWoundCare. 2016;29:316–21.

36.MoreiraCNO,MarquesCB,SaloméGM,CunhaDR,Pinheiro FAM.Healthlocusofcontrol,spiritualityandhopeforhealing inindividualswithintestinalstoma.JColoproctol.