www.rbceonline.org.br

Revista

Brasileira

de

CIÊNCIAS

DO

ESPORTE

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Mechanical

stiffness:

a

global

parameter

associated

to

elite

sprinters

performance

Fernando

López

Mangini

a,

Gabriel

Fábrica

b,∗aUniversidaddelaRepública(UDeLaR),FacultaddeMedicina,UnidaddeInvestigaciónenBiomecánicadelaLocomoción

Humana,Montevideo,Uruguay

bUniversidaddelaRepública(UDeLaR),FacultaddeMedicina,DepartamentodeBiofísica,Montevideo,Uruguay

Received24July2013;accepted12March2014 Availableonline12March2016

KEYWORDS

Stiffness; Sprint; Biomechanics; Performance

Abstract Thisstudyanalyzesvertical stiffnessasaglobalparameterthatcouldbedirectly associatedtosprinter’sperformance.Weevaluatedverticalstiffness,performance,heartrate andlactateconcentrationonfifteenmalesprintersthatranonatreadmillatgaittransition speedand13kmh−1.VerticalStiffnesswasdeterminedbytheratioofthevertical accelera-tion peakandmaximum displacementofthecenterofmass.Physiologicalparameterswere measuredthroughouttheexperimentalprocedureandperformancewasestimatedbyathlete’s timerecordson100mtrackrace.Asexpected,verticalstiffnessandheartrateincreasedwith runningspeed.Wefoundahighcorrelationbetweenheartrateandverticalstiffnessatgait transitionspeed.However,at13kmh−1,lactatepeakshowedahighercorrelationwithvertical stiffness,suggestingagreaterparticipationoftheanaerobicsystem.Aninverserelationship betweenperformanceandverticalstiffnesswasfound,wherefasterathleteswerethestiffer ones.Performanceandlactatepeakpresentedthesameinverserelationship;fasterathletes hadhigherlactatepeaks.Asaresult,fasterathleteswerestifferandconsumemoreenergy.All inall,thesefindingssuggestthatmechanicalstiffnesscouldbeapotentialglobalparameterto evaluateperformanceinsprinters.

©2016Col´egioBrasileirodeCiˆenciasdoEsporte.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrights reserved.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Rigidez; Corridade velocidade; Biomecânica; Desempenhofísico

Rigidez mecânica: um parâmetro global associado com desempenho em velocistas deelite

Resumo Esteestudoanalisaarigidezverticalcomoumparâmetroglobalquepoderiaser dire-tamenteassociadoaodesempenhoemvelocistas.Avaliou-searigidezvertical,odesempenho, afrequênciacardíacaeaconcentrac¸ãodelactatoem15velocistasdosexomasculino,todos altamentetreinados,quecorreramemumaesteiraàvelocidadedetransic¸ãoea13km.h−1.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:cgfabrica@gmail.com(G.Fábrica).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbce.2016.02.004

Arigidezverticalfoideterminadapelarazãoentreopicodeacelerac¸ãoverticaleo desloca-mentomáximodocentrodemassa.Osparâmetrosfisiológicosforammesuradosnacoletade dadoseodesempenhofoiestimadoporregistrosdetempoem100metrosdecorrida.Como esperado,arigidezverticaleafrequênciacardíacaaumentaramcomavelocidade.Arigidez eafrequênciacardíacaobtiveramaltacorrelac¸ãonamenorvelocidade.Contudo,a13km.h−1 opicodelactatomostroualtacorrelac¸ãocomarigidez,oquesugereumamaiorparticipac¸ão dosistemaanaeróbico.Umarelac¸ãoinversafoiachadaentrerigidezeregistrosdetempo,nos quaisosatletasmaisrápidossãoosmaisrígidos.Alémdisso,osatletasmaisrápidosforamos queapresentaramosmaiorespicosdelactato.Assim,esteestudosugerequearigidezvertical poderiaserumparâmetroglobalparaavaliarodesempenhodosvelocistas.

©2016Col´egioBrasileirodeCiˆenciasdoEsporte.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Todosos direitosreservados.

PALABRASCLAVE

Rigidez; Sprint; Biomecánica; Rendimiento

Rigidez mecánica: un parámetro global asociado con el rendimiento en velocistas deélite

Resumen Esteestudioanalizalarigidezverticalcomounparámetroglobalquepodríaestar directamenterelacionadoconelrendimientoenvelocistas. Seevaluó larigidezvertical,el rendimiento, la frecuencia cardíaca y la concentración delactato en 15velocistasde sexo masculino, muy entrenados, que corrieron en una cinta a la velocidad de transición y a 13km/h−1.Larigidezvertical secalculó porelcocienteentreelpicode aceleración verti-calyeldesplazamientomáximodelcentrodemasa.Losparámetrosfisiológicossemidieron duranteelprocedimientoexperimentalyelrendimientoseestimóatravésdeltiempodecada atletaen100mllanos.Comoeradeesperar,larigidezverticalylafrecuenciacardíaca aumen-taronconla velocidad.Seencontróunaaltacorrelaciónentrefrecuenciacardíacayrigidez verticalalavelocidadmásbaja.Sinembargo,a13km/h−1,elpicodelactatomostróunaalta correlaciónconlarigidezvertical,loquesugeríamayorparticipacióndelsistemaanaeróbico. Seencontróunarelacióninversaentreelrendimientoylarigidezvertical,dondelosatletasmás rápidosfueronmásrígidos.Asimismo,elrendimientoyelpicodelactatopresentaronlamisma relacióninversa;losatletasmásrápidosmostraronlospicosmásaltosdelactato.Por consi-guiente,losatletasmásrápidosfueronmásrígidosyconsumieronmásenergía.Estosresultados sugierenquelarigidezmecánicapodríaserunparámetroglobalparaevaluarelrendimiento delosvelocistas.

©2016Col´egioBrasileirodeCiˆenciasdoEsporte.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Todoslos derechosreservados.

Introduction

Arunningsprintercoordinatestheactionsofmanymuscles, tendons, and ligaments in its leg so that the overall leg behaves like a single mechanical spring during ground contact(Farleyetal.,1993).Infact,thesimplestmodelofa runningsprinterisaspring-masssystemconsistingofalinear springrepresentingthestancelimbandapointmass equiv-alenttobodymass (Blickhan,1989;Mcmahon and Cheng, 1990).Duringsupport,verticalforcecomponentisactingon thespringandthusmechanicalstiffnesscanbecalculated fromtheratioofthisforcetothechangeinspringlength.

The spring mass model has been used in optimization studies (Alexander, 2003) and totest hypothesis that are directly related tosport andtraining fields (Morin etal.,

2011; DiMichele et al.,2012).The reasons for usingthis

modelintheseareasaremainlyitssimplicityandglobality sinceevaluations generallyhave the tendency toanalyze oneorafewparametersonly.

Assumingthespring massmodel,previous studieshave used different methods and equipments for estimating mechanical stiffness when running (Brughelli and Cronin, 2008).Oneoftheapproachesmostcommonlyusedis verti-calstiffness(Kvert)(Mcmahon etal.,1987;Cavagnaetal.,

1988; Morin et al., 2005, 2011; Di Michele et al., 2012).

This parameter relatestothepeakvertical forceand the vertical motion of the center of mass during the contact with the ground (Brughelli and Cronin, 2008). Both, the force peak and the displacement of the center of mass depend on muscular activation, fiber type and muscular volume (Herzog, 2000) and is thought to influence sev-eralathleticvariables,includingrateofforcedevelopment, storageofelasticenergy,stridefrequency,groundcontact time and sprint kinematics (Farley and Gonzalez, 1996;

Mcmahon and Cheng, 1990). In this way, changes in Kvert

It is widely known that strengthis amajor qualityfor athletestodevelop,thusitiscloselyassociatedtorunning speed. All elite sprinters have a common feature; huge leanmuscleswithhigh percentageofexplosivefibers that areintensivelyactivatedwhen racing(Kuboetal., 2011). Duringeach stepphase,athletes performmaximum force in averyshortperiodof time,recruitinghigh percentage ofmusclefibersandactivatingcontractileelementsto gen-erate intensive stretch-shorteningcycles in acoordinated manner (Nigg et al., 2000). Therefore, maximum power is perform during ground contact, increasing speed and improvingtimerecords.

Having a largermuscular volume,build up byfast and explosivefibers,withalargercrosssectionthanslowfibers andahighpercentageofactivatedfibers,coulddetermine anincreaseinforcepeakduringgroundcontactphase lead-ingtoanincreaseinKvert.

Nonetheless,an athletewithalargermuscular volume and ahigh percentage of activatedfibers would consume moreenergy.Kvert dependsdirectly ontheforce peakand thisonmusclecharacteristicsthatwoulddetermindenergy consumption. Energy consumption during exercise can be estimated throughout different physiological parameters such as heart rate and blood lactate concentration. The analysisoftheseparameterswouldprovidefurtherinsight onKvertvaluesconsideringthemasarealfeedbackof phys-iologicalprocesseshappeninginsidemuscletendonunitof thelimbs.

Theaimofthisstudyistoprovideabetter understand-ing ontheimportance ofmechanical stiffnessasa global parameter that could be directly associated to athlete’s performance.

Our hypothesis isthat athletes withhighermechanical stiffnesswillconsumemoreenergyandwillhavefastertime recordsin100m.

For that purpose, we analyzed Kvert of elite sprinters througha3D filmingandreconstructionprocedureat con-trolledconditionsandlactateconcentrationandheartrate to assay their relationship withathlete’s performance. If the hypothesis is correct,the physiological and mechani-calparametersstudiedhereshouldfollow thesametrend ofchange andhave ahigh correlation withathlete’stime records.Asaresult,mechanicalstiffnesscouldbea poten-tialglobalparametertopredictperformanceinsprinters.

Methods

Experimentalapproachtotheproblem

Thestudy designiscomposedbytheanalysisofthree dif-ferentvariables.

By using a three dimensional filming method (cineme-try),athlete’smechanicalstiffness(Kvert)wasassayed.This method,basedonthespring-massmodel,providesinsights on the motion of the center of mass when running. Sec-ondly, physiological parameters such as lactate peak and heartrateweremeasuredtoanalyzeenergyconsumption. These canbeconsidering asarealfeedbackof the physi-ologicalprocesseshappeninginsidemuscletendonunitsof thelimbs.

Finally,wemeasuredathlete’sperformancebytheirtime recordsin100mtrack race.Timerecordswere measured undercontrolledconditions(sameday,track,distance,wind speedandchronometer)forallsprinters.

With these information, we tested our hypotheses to provideabetter understanding onthe importanceofKvert asaglobal parameterthatcouldbedirectly associatedto athlete’sperformance.

Subjects

Asampleoffifteenmaleathletes,allhighlytrainedsprinters (19.7±1.28years,69.50±2.68kg)voluntarilyparticipated inthisstudy.Thesamplewasconvenientlyselectedamong athleteswiththebesttimerecordsin100minthecountry. The sample size (n) was estimated throughout a comparisonmodel:

n= 2(Za+Zb)

2∗S2 d2

where n=number of athletes, Za and Zb=risk values, S2=variance of K

vert (taken from bibliography) and d=minimumdifferencedetectedwhencomparingtwoKvert valuesatdifferentspeeds.Also,weconsideredunilaerality andset˛=0.05andˇ=0.05.

Theexclusioncriteriaconsidered werethepresenceof anyinjurywithinthelast6monthorifthetrainingperiod wasdifferentfrompre-competition/competition.Oncethe sample was selected, none of the individuals had to be excludedfromthetrial.

This study complied with the requirements of the local Committee for Medical Research Ethics and cur-rentUruguayanlawandregulations.Theparticipantswere informed about the objectives and characteristics of the study,andtheirconsentwasobtained.

Procedures

Performance was measured by athlete’s time records on 100mtrackrace.Athleteswererequestedtoracea100m onan officialtrail in theNational AthleticStadium. Time recordswere measuredundercontrolledconditions(same day,track, distance,windspeed andchronometer)for all sprinters.

After evaluating performance, athletes were taken to theLaboratoryofMovementintheHospital deClínicas to evaluateKvertandphysiologicalparameters.

Athletes were dressed up in black tight clothes and coveredwith18whitemarkersindifferentanatomical land-markstoidentify them for subsequent digitalization. The selectedpointswerethefifthmetatarsal,lateralmalleolus, femoralcondyle, greater trochanter, acromion, sphenoid, lateralepicondyleofthehumerus,radialstyloidprocessand headofthethirdmetacarpal.Priortoperformingthe exper-imental procedures, two anthropometric variables were measured: body mass and leg length (trochantericheight measuredfromthegreatertrochantertothefloor).

invelocity(ArampatzisandMetzle,1999).Duringthefirst 5min,athletesranattheirgaittransitionspeedestablished byFreud’sequation:

V2=0.5.g.l

where V is the running speed, 0.5 is Freud’s number for gait transition speed, g is acceleration due to gravity (9.8ms−2onearth)andlistheleglengthinmeters(Saibene

and Minetti, 2003). The remaining 5min athletes ran at

13kmh−1,speedat whichmuscles workmainly in isomet-ric contraction (Fisher, 2010). We selected these running speedssincethemodelweareusingtocalculateKvert per-fectlyadjustsandisvalidatlowrunningvelocities. Inthis way,althoughwearenotmeasuringKvert attheusualhigh speedof a race, thisparameter calculated at low speeds reflectstheglobalmechanic characteristicsof theathlete

(Cavagnaetal.,1988).

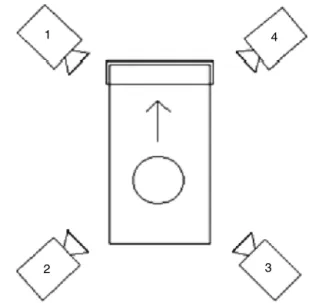

Images were recorded with 4 synchronized DCR-H28E digitalvideocameras,thesewereplacedon950ALS UNO-MATtripodsfollowinga90degreeanglelayoutwithineach other toensure that athlete’s sagital plane wascaptured bytwo cameras(Fig.1). In thisway, a three-dimensional reconstructionwasperformedtodeterminethepositionof athlete’scenterofmass(CM)andcalculatethemechanical stiffnessthroughoutKvert.

Oncethefilmingprocesswasfinalized,imageswere cap-turedandloadedinDvideowsoftware(DigitalforVideofor BiomechanicsWindows32bits).Thisprogramallows decen-tralizingthefieldsthatcomposetheimagesofeachframe ofthevideosothatthefrequencyofdataacquisitioninthis workwas50framespersecond(Barrosetal.,1999;Figueroa

etal.,2003).

Upon finishing the above process, the position coor-dinates of the markers placed over specific landmarks were determined by digitalizing each marker referenced to a three dimensional coordinate system associated to a calibration volume. The system used for calibration, was chosen according to the International Society of

1 4

3 2

Figure1 Schematiclayoutofthecamerasplacedroundthe

treadmill.Thearrowindicatesmovementdirection.

Biomechanics recommendations, in order to unify the kinematics datacommunication. Throughout a 3-D recon-struction,athree-columnmatrix wasobtained,describing thepositioncoordinatesofthemarkers.

The digitalized sequence was selected from 10 step cyclesof thelast minuteof each runningspeed toassure less stepvariability (Fisher, 2010). After establishing this sequenceinonecamera,wecalculatedtheframerangeto acquirethesamerangeinallcameras.Thustoperformthis, we synchronizedthe deviceswithasoundsignal thatwas recordedinthevideoandreadbythesoftware.TheCM coor-dinates weredetermined by 3D reconstructionanalysis in Matlab7.0® (Mathworks,Inc.),consideringthecoordinates ofthepartialcenterofmassofthefeet,legs,thighs,hands, forearms,arms,trunkandhead.Knowingthepositionofthe CMineachstep,weproceededtocalculatetheacceleration oftheCMbyderivingitspositiontwicewithrespecttotime. Fromthe accelerationcurve we determinedtheeffective contacttimeforeachstancephase(Cavagna,2006).Using thistimewecalculatethemaximumdisplacement(MD)of theCMfromthepositioncurve(Cavagna,2006).

Finally,the effective vertical stiffness wasdetermined bytheratioof theverticalaccelerationpeak(avmax)and

MD(BrughelliandCronin,2008)oftheCM.

Kvert=avmax.MD−1

Twophysiologicalparameterswereanalyzedinthisstudy (heartrateandlactateconcentration).Heartratewas mon-itored prior to performing the experimental procedures (basal heart rate) and during both running speeds by a Nike triax c8 heart rate monitor. The lactate concentra-tionwasdeterminedbyaRocheAccutrendpluslactimeter. This device worked throughout a colorimeter method to determine the amount of blood lactate concentration.To carryoutthemeasurementproceduresweused20specific reagentsforlactateand20disposablelancets(allpurchased fromRoche).Fourlactatemeasurementswereperformedto allathletes.Thefirstonewascompletedbeforethestartup oftheprotocol(basallactateconcentration)andtheother threewere accomplished2,5 and8min afterthe experi-mentalprocedureswerefinalized.

Statisticalanalysis

Kvert at both speeds was plotted against athlete’s time records,andlactatepeakwasplottedagainstathlete’stime records.

Pairedsample t-test(p<0.01) wereperformed to ana-lyze howKvert and physiological parameters change when increasingrunningspeed.

Pearsoncorrelationswereimplementedbetween:

- Kvertandphysiologicalparametersatbothspeeds - Kvertandathlete’stimerecordson100m

- Lactatepeakandathlete’stimerecordson100m.

Table1 Mean andstandarddeviation ofKvert andheart ratebothrunningspeedsp≤0.01isthesignificanceofthe changeoftheseparametersfromgate transitionspeed to 13kmh−1.

Variable Gaittransitionspeed 13kmh−1 p

Kvert(s−1) 161.5±22.9 194.5±27.4 0.001 Heartrate 143.9±11.2bpm 177.2±5.7 0.001

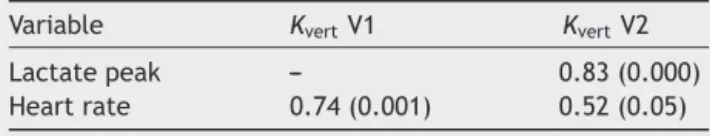

Table2 Resultsofcorrelations,notethattheanalysisare notperformedforlactatepeakandKvertV1,sincethe sam-plesweretakenafterthesecondrace(13kmh−1).Thelevel ofsignificanceisshownbetweenbrackets.

Variable KvertV1 KvertV2

Lactatepeak --- 0.83(0.000) Heartrate 0.74(0.001) 0.52(0.05)

Results

Allathletesanalyzedincreasedtheirheartrate,blood lac-tateconcentrationandKvert whenenhancingrunningspeed

asestablishedinpreviousinvestigations(Kerdoketal.,2002;

BrughelliandCronin,2008;Fisher,2010).

Paired sample t-tests (p<0.01) showed significant changesinheartrateandKvertwhenraisingrunningvelocity fromgaittransitionspeedto13kmh−1(Table1).

Also, blood lactate concentration exhibited an impor-tant peak (7.63±2.41mmoll−1) 2min after finalizing the experimental procedures which was significantly higher (p<0.01)thanthebasalconcentrationobtainedinthiswork (1.89±0.4mmoll−1).

Pearson correlations between heart rate and Kvert for gait transition speed were higher than the ones found at 13kmh−1,andlactatepeak,washighlyassociatedtoK

vert values(r=0.83)whenrunningat13kmh−1(Table2).

HighcorrelationswherefoundwhenplottingKvertvalues measuredatgatetransitionspeedandat13kmh−1against sprinter’s time records in 100m (r=0.907 and r=0.922 respectively), where the fastest sprinters (shortest time record)weretheoneswiththehighestKvert(Fig.2).

The same inverse relationship and similar correlation (r=0.95)wasfoundwhenplottingbloodlactatepeakagainst

300

Kv

er

t (s

–2)

Sprinter’s time records in 100 meters (s)

Kvert values at gait transition speed Kvert at 13 Km.h–1

250

200

150

100

50

0

10.7 10.8 10.9 11 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5

Figure 2 Kvert measured at gait transition speed and at

13kmh−1vstimerecordsin100m.

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

10.7 10.8 10.9 11 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5

Lactate peak (mmol.L

–1)

Sprinter’s time records in 100 meters (s)

Figure3 Lactatepeakvstimerecordsin100m.

athlete’stimerecords,wherethefastestathleteshadthe highestlactatepeaks(Fig.3).

Discussion

Inthis study, we focuson howKvert is associated toelite athlete’s performance. Therefore, to achieve this aim, we calculated Kvert and analyzed heart rate and blood lactate concentration to estimate energy consumption, considering these variables asa realfeedback of physio-logical processes happening inside muscle tendon unit of thelimbs. To estimate Kvert, we useda method based on imagingreconstruction. Although thiscouldbeconsidered asalimitationofthestudymethodssinceforceplatesare moreprecise,we understandit isfundamental toanalyze and evaluate the study parameters at controlled speed. Thus,weconsideredcinemetryasthebestoption.

We used two different running speeds (gait transition speed and 13kmh−1) to confirm that K

vert varies when increasingrunningvelocity(ArampatzisandMetzle,1999). Weselectedtheserunningspeedssincethemodelwe are usingto calculate Kvert better adjusts and is valid at low runningvelocities. Athighervelocities,asymmetriesoccur intheverticaldisplacementoftheCMduringtheeffective ground contactphase(Cavagnaet al.,1988). In thisway, althoughwearenotmeasuringKvertattheusualhighspeed ofarace,thisparametercalculatedatlowspeedsreflects theglobalmechaniccharacteristicsoftheathlete.

TheKvert average valuesfound forgaittransitionspeed (161.5±22.9s−2)andfor13kmh−1(194.5±27.4s−2),were slightly below the values usually established in previous investigations.Forinstance,Ferrisetal.(1999)found val-ues of 18kNm−1 (225s−2) when running at 10.8kmh−1

(Ferrisetal.,1999);DuttoandSmith(2002)founddataof

23.5kNm−1(293s−2)forarunningspeedof14kmh−1(Dutto

andSmith,2002).

values(p=0.001) when enhancing running speed which is coherent with previous studies findings (Arampatzis and

Metzle,1999; Brughelli andCronin, 2008). The significant

changes in Kvert when raising running speed have been fully explained in former studies by enhancing the force peak and decreasing the displacement of the CM during thestance phase (Brughelli andCronin, 2008). These dif-ferences in force and displacement are determined by changes in muscular contractile capacity. This combined withmetabolicchangescouldmaketheneuromuscular sys-temregulatethemuscle-tendonstiffnessbyincreasingthe level of pre-activation and thus affecting global stiffness

(Fisher, 2010). It has been demonstrated that enhancing

running speed, increases Kvert and as a result, a smaller amount of elastic energy is used (Brughelli and Cronin, 2008). The supporting explanation for this statement is that Kvert depends onboth, the vertical acceleration and the effective deformation of the lower limb, while the elasticenergydependsonthesquareddeformation. There-fore,thesmaller effective deformationof the lowerlimb due to the increase on running speed becomes deter-minant in the use of elastic properties (Fisher, 2010). Thus,this should reflect an increase onenergy consump-tion, as analyzed in previous studies where Kvert was assayed in different running speeds in fatigue condition

(Borranietal.,2003;Candauetal.,1998;Slawinskietal.,

2008).

Inthis paper,wefound thatheart rateincreaseswhen enhancing running speed and that blood lactate concen-tration shows a significant peak (7.63±2.41mmoll−1) compared to the basal values (1.89±0.4mmoll−1), con-firming that higher energy is consumed. In addition, increasingrunningspeedimpliesamajoreffortandagreater number of muscle fibers activated, thus raising muscu-lar activation andthe force performed during the ground contactphase(Herzog,2000).Asaresult,moreenergy(ATP) andoxygen is consumedby the musclefibers that is sup-portedbyanintensifybloodsupplydrivenfromtheheart, increasingitsrateandvolumeofventricularejection(Nigg etal.,2000).Pearsoncorrelationsbetweenheartrateand Kvert forgaittransitionspeed(r=0.74)washigherthanthe one found at 13kmh−1 (r=0.52), probably becausewhen runningatalowervelocity,themainsystemrestoringATP is the aerobic system. On the other hand, running at a fasterspeed derives in agreater muscleactivity implying an increase on the amount of lactate concentration. The presence of this molecule in the muscle fibers, promotes theacidificationofthecellsenvironmentwhichspeedsup oxygenrelease tothe tissues, profiting cellular breathing (Niggetal.,2000).Wefoundthatlactateconcentration,was highlyassociatedtoKvert values(r=0.83)whenrunning at 13kmh−1whileheartratecorrelationdecreased(r=0.52). Thisshowsanimportantparticipationoftheanaerobic sys-teminrestoringATP.

Wefound thatfasterathleteswerestiffer andalsothe onesthatreachedthehighestlactatepeak,thusconsuming moreenergy.Therefore,changesinphysiologicalvariables highlighttheimportanceofKvertasaglobalparameter. Hav-ingalargermuscularvolumebuildupbyfastandexplosive fiberswithalargercrosssectionthanslowfibersandahigh percentageofactivatedfiberscoulddetermineanincrease in force peak during ground contact phase leading to an

increase in Kvert.This increase in muscular activation due toalargervolumewillconsumemoreenergy.Asaresult, stiffersprinterswouldconsumemoreenergy.

ThefindingsofthisstudysuggestthatKvertisanimportant determinant and a potential global parameter to evalu-atesprinter’sperformance.Consideringthatitismeasured whenracingandsimpletoevaluate,thisparameterhasan importantpracticalapplicationinthecoachingfield.Inthis sense, for future studies we will focus on a longitudinal approachtoanalyzehowdifferentcapacitiessuchaspower, explosive force andcoordination canaffect Kvert and ath-lete’sperformance.Uptodate,therehavebeennostudies thatanalyzetheeffectsoftraininginotherwaysof estimat-ingmechanicalstiffness,suchaslegstiffness,andrunning speed.

Conclusions

Whenincreasingrunningspeed,heartrateandKvertfollow thesametrendofchange.

At gaittransition speed, Kvert is highly correlatedwith heartrate.

At13kmh−1K

vertishighlycorrelatedwithlactatepeak. Our results suggest that the fastest athletes have a greatermechanicalrigidityandconsumemoreenergy.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

AlexanderRMcN.Modellingapproachesinbiomechanics.PhilTrans RSocLondB2003;358:1429---35.

ArampatzisBG,MetzleV.Theeffectofspeedonlegstiffnessand jointkineticsinhumanrunning.JBiomech1999;32:1349---53.

BarrosRML,BrezinkoferR,LeiteNJ,FigueroaPL.Desenvolvimento eavaliac¸ãodeunsistemaparaanálisetridimensionalde movi-mentoshumanos.RevBrasEngBioméd1999;15:234---9.

Blickhan R. The spring-mass model for running and hopping. J Biomech1989;22:1217---27.

BorraniF, Candau R,Perrey S, Millet GY, Millet GP,RouillonJD.

DoesthemechanicalworkinrunningchangeduringtheVO2slow

component?MedSciSportsExerc2003;35:50---7.

BrughelliM,CroninJ.Influenceofrunningvelocityonvertical,leg andjoint stiffness:modelingandrecommendationsforfuture research.SportsMed2008;38:647---57.

Candau R, BelliA, Millet GY,Georges D,BarbierB, RouillonJD.

Energy costand runningmechanics duringa treadmillrun to voluntaryexhaustioninhumans.EurJApplPhysiolOccupPhysiol 1998;77:479---85.

CavagnaGA,FranzettiP,HenglundN,WillemsP.Thedeterminants ofthestepfrequencyinrunning,trottingandhoppinginman andothervertebrates.JPhysiol1988;399:81---92.

CavagnaGA.Thelanding-take-offasymmetryinhumanrunning.J ExpBiol2006;209:4051---60.

Di Michele R, Del Curto L, Merni F. Mechanical and metabolic responsesduringahigh-intensitycircuittrainingworkoutin com-petitiverunners.JSportsMedPhysFitness2012;52:33---9.

FarleyC,GlasheenJ,McMahonT.Runningsprings:speedandanimal size.JExpBiol1993;185:71---86.

FarleyCT,GonzalezO.Legstiffnessandstridefrequencyinhuman running.JBiomech1996;29:181---6.

FerrisDP,LiangK,FarleyCT.Runnersadjustlegstiffnessfortheir firststeponanewrunningsurface.JBiomech1999;32:787---94.

FigueroaPJ,LeiteNJ,BarrosRML.Aflexiblesoftwarefortracking ofmarkersusedinhumanmotionanalysis.ComputMethodsProg Biomed2003;72:155---65.

FisherG. AnálisedaMecânicadaCorridacomesemo efeitoda Fadiga[Dissertac¸ãoMestrado].PortoAlegre:Ciênciasdo Movi-mento Humano, Universidade Federal do Rio Grandedo Sul, UFRGS;2010.

HerzogW.Cellularandmolecularmusclemechanics.In:HerzogW, editor.Skeletalmuscle mechanics:from mechanismsto func-tion.NewYork:JohnWiley&Sons,Ltd;2000.p.33---52.

KerdokAE,BiewenerAA,McMahonTA,WeyandPG,HerrHM. Ener-geticsandmechanicsofhumanrunningonsurfacesofdifferent stiffness.JApplPhysiol2002;92:469---78.

McmahonTA, ValiantG, FrederickEC.Grouncho running.JAppl Physiol1987;62:2326---37.

Kubo K, Ikebukuro T, Yata H, Tomita M, Okada M. Mor-phological and mechanicalproperties of muscle and ten-don in highly trained sprinters. J Appl Biomech 2011;27: 336---44.

McmahonTA,ChengGC.Themechanicsofrunning:howdoes stiff-nesscouplewithspeed?JBiomech1990;23:65---78.

Morin J, Delleau G, Kyrolainen H, Jeannin T, Belli A. A simple methodformeasuringstiffnessduringrunning.JApplBiomech 2005;21:167---80.

Morin JB, Tomazin K, Edouard P, Millet GY. Changes in running mechanics and spring-mass behavior induced by a mountain ultra-marathonrace.JBiomech2011;44:1104---7.

NiggB,MacIntoshB,MesterJ.Biomechanicsandbiologyof move-ment.Champaign,IL,USA:HumanKinetics;2000.

Saibene F, Minetti AE. Biomechanical and physiological aspects of legged locomotion in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol 2003;88:297---316.