w w w . j c o l . o r g . b r

Journal

of

Coloproctology

Review

Article

Short

bowel

syndrome:

treatment

options

Rosário

Ec¸a

a,∗,

Elisabete

Barbosa

a,baUniversidadedoPorto,FaculdadedeMedicina,Porto,Portugal

bCentroHospitalardeSãoJoão,Servic¸odeCirurgiaGeral,Porto,Portugal

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory: Received25June2016 Accepted6July2016

Availableonline7September2016

Keywords:

Shortbowelsyndrome Intestinaladaptation Surgicalmanagement

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Introduction:Shortbowelsyndrome(SBS)referstothemalabsorptivestatethatoccurs fol-lowingextensiveintestinalresectionandisassociatedwithseveralcomplications. Methods:TheresearchforthisreviewwasconductedinthePubmeddatabase.Relevant scientificarticlesdatedbetween1991and2015andwritteninPortuguese,SpanishorEnglish wereselected.

Results:Severaltherapies,includingnutritionalsupport,pharmacologicaloptionsand sur-gicalprocedureshavebeenusedinthesepatients.

Conclusions:Overthelastdecadesnewsurgicalandpharmacologicalapproachesemerged, increasingsurvivalandqualityoflife(QoL)inpatientswithSBS.AllSBSpatientsoughtto haveanindividualizedandmultidisciplinarycarethatpromotesintestinalrehabilitation.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradeColoproctologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.This isanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Síndrome

Intestino

Curto:

abordagens

terapêuticas

Palavras-chave:

SíndromeIntestinoCurto Adaptac¸ãoIntestinal Tratamentocirúrgico

r

e

s

u

m

o

Introduc¸ão:ASíndromedoIntestinoCurto(SIC)resultadaperdadacapacidadedeabsorc¸ão dointestinoapósressec¸ãointestinalextensaeestáassociadaadiversascomplicac¸ões. Métodos:Estarevisãofoirealizadacombaseemartigoscientíficosoriginaispesquisadosna basededadosMEDLINEviaPubmed,nalínguaportuguesa,inglesaeespanhola,comolimite temporalde1991a2015.

Resultados:Otratamentoinstituídopodeseranívelnutricional,farmacológicooucirúrgico. Conclusões:Aolongodasúltimasdécadassurgiramnovasabordagensterapêuticas cirúrgi-casenão-cirúrgicasquemelhoraramasobrevivênciaeaqualidadedevida(QoL)destes pacientes.Deve-se estabelecer uma abordagem multidisciplinar e individualizadapara garantiramelhorreabilitac¸ão.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradeColoproctologia.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:rosarinho.eca@gmail.com(R.Ec¸a). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcol.2016.07.002

Introduction

Definition

Shortbowelsyndrome(SBS)ischaracterizedbyreduced abil-ityofdigestionandabsorptionduetoasurgicalresection,a congenitaldefect,or bowel disease.1–5 Thisabsorption

fail-ure results in nutritional and electrolyte imbalances.1,3,5–7

AccordingtoBuschmanetal.8,9inadultsSBSoccurswhenthe

anatomicallengthoftheremainingsmallintestineis<200cm. Animportantaspect isto distinguishbetween SBSand intestinalfailure(IF).IFreferstoaconditionresultingfrom obstruction,dysmotility,bowel resectionsurgery,congenital defect,oradiseaseassociatedwithlossofabsorptivecapacity, inwhichSBSisitsmostfrequentcause.4

Epidemiology

TheincidenceandprevalenceofSBShaveincreasedoverthe pastdecades.10InEurope,theestimatedincidenceand

preva-lenceis2-3permillionand4permillion,respectively.4,7,8,11

Thisconditionoccursinapproximately15%ofadults undergo-ingintestinalresection(75%inextensiveintestinalresection and 25% in sequenced resections).4,12 However, the actual

values are difficult to determine, since this is a condition that includesall formsoflength/function reductionofthe smallintestineassociatedwithmalabsorptionsyndrome,and moreover,its notificationisnotdetailed.Thebestestimate isbasedonthenumberofpatientsreceivinglong-term Par-enteralNutrition(PN)and/orintravenous(IV)fluids,giventhat asignificantpercentageofpatientsunderPNhaveSBS(35%). However,patientsnolongertreatedwithPNarenotincluded, andthusthenumberofSBSpatientsisunderestimated.7

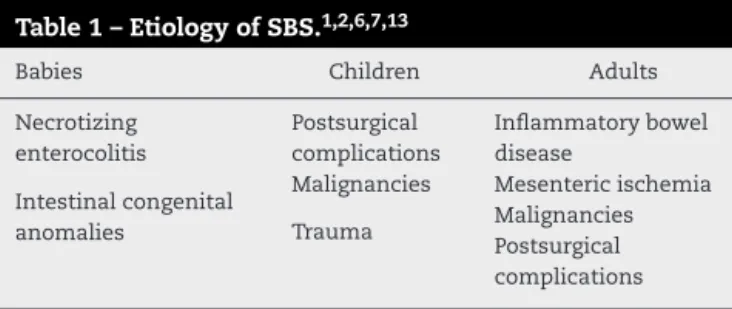

Etiology

Theetiologyismultifactorialandcoversallagegroups.8SBS

canresultfromacongenitaloracquiredpathologyrequiring anextensiveresectionofthesmallintestine(Table1).1,2,6,7,13

Materials

and

methods

Thisreviewwasbasedonoriginalscientificarticlessearched inMEDLINEviaPubMed,inPortuguese,English,andSpanish idiom,withatimelimitfrom1991to2015.Thesurveywas conductedusing the terminology “short bowel syndrome”; “AdaptationANDSBS”;“NutritionANDSBS”;

“Pharmacolog-Table1–EtiologyofSBS.1,2,6,7,13

Babies Children Adults

Necrotizing enterocolitis

Postsurgical complications

Inflammatorybowel disease

Intestinalcongenital anomalies

Malignancies Mesentericischemia

Trauma Malignancies

Postsurgical complications

icalManagementANDSBS”;“SurgicalTreatmentANDSBS”; “NewapproachesANDSBS”;“QualityoflifeANDSBS”.Papers ofinterest foundthrough thereferences were searched.In total,96publicationswereincluded.

Results

Pathophysiology

Thesmallintestinehasahighadaptivecapacityinthefaceofa substantialreductionofitslength;thus,inmostcases, resec-tions uptohalfitssizearewell-toleratedinthelongterm. However,asmallintestinewithlessthan200cmpresentsan increasedriskfortheoccurrenceofascenarioof malabsorp-tion,andhencemalnutrition.14–17

ThemanifestationsofintestinalresectionandSBSarea resultof15,17:

1. thelossofintestinalabsorptionsurface; 2. thelossofspecificsitesofabsorption;

3. adecreaseinproductionofintestinalhormones; 4. thelossoftheileocecalvalve.

MostSBScasesoccurafterextensiveresections,andthe lengthoftheremainingintestineisthemajordeterminantof prognosisandofclinicalconsequences.15,16

Thelossofnutrientandfluidabsorptioncapacitiesheralds theonsetofmalnutritionandelectrolyteimbalances; absorp-tionofmacro-nutrients,mainlycarbohydrates(CH)andlipids, arethemostaffected.2,5,6,15,18–21

Thepresenceofalargeamountofunabsorbedsolutesin the intestinal lumen resultsin anincreasedosmotic pres-sure and in the onset of one of the major symptoms of SBS, diarrhea, usually more intense at an initial stages. Anothersymptomreportedissteatorrhea,resultingfromthe decreasedreleaseandactivityofpancreaticenzymesandbile salts,whichmakesemulsification,digestionandabsorption oflipidsandfat-solublevitaminsdifficult.Ontheotherhand, deficienciesofwater-solublevitaminsarelessfrequentsince, inmostpatients,theduodenum,andproximaljejunum seg-mentsarepreserved.2,6,14–16

In addition, resectionofspecific locations on thebowel compromisesabsorption:removingthedistalileumprevents reabsorptionofbilesaltsandabsorptionofvitaminB12;the absence of an “ileal brake” reduces further the ability to digest and absorb thoughgastric hypersecretion,increased gastric/intestinal emptying, resulting in worsening of the diarrheaandsteatorrhea;thepresenceofthecolonis essen-tialfortheintestinaladaptation,bysubstantiallyincreasing fluidretention capabilityand,moreover,the capacityofits bacteriatodigestCHintoabsorbableshortchainfattyacids (SCFAs).1,2,5,6,14,17,18–22Itisalsoimportanttopreservethe

ileo-cecalvalvesinceitslosswillallowupstreamgrowthofcolonic bacteria.5,15,19

are critical for the neurohormonal control ofthe digestive process.Thus,thedecreasedproductionwillresultinafaster gastricemptying,hypergastrinemiaandincreasedintestinal transit.8,14,17,22

Asfortypesofsmallbowelresection,themostcommonin SBSare15,16,19,22:

1. Resectionofpartofjejunumandsometimesofileum,with anastomosisoftheremainingportions.

2. Resectionoftheileumwithajejunal–colicanastomosis. 3. Resectionoftheileum,colonandpartofjejunum,witha

jejunostomy.

Foreach typeofresection,anatomicalandphysiological changescanleadtodifferentclinicalpictures.Typically,the jejunalresectionisthebest-toleratedoption,thoughless fre-quent,takingintoaccountthatthepreservationoftheileum andcontinuityofthecolon(structureswithgreateradaptive capacity)ensuresthemaintenanceofasuitabledigestive pro-cess.Accordingly,patientsundergoingjejunostomyarethose withhighernutritionalandfluiddeficits.5,15,19

Post-intestinalresectionadaptation

Adaptation is an individualized process that depends on factorsrelatedtotheintestineandtothepatient.4,6This

phe-nomenontakes place ina period ofabout 2 years,and is dividedintothreephases:acute,adaptive,andmaintenance phases(Fig. 1), duringwhichthe remainingintestine com-pensatesforthelossincurredthroughstructuralandmotility changes.1,2,4,14,20,23

Thesuccessofthisadaptationdependsonboththelength andtheportionofresectedbowel,andwilldeterminewhether thepatientwillrequireapermanentornon-permanenttotal parenteralnutrition(TPN),afactwithgreatimpactonquality oflife(QoL)andprognosis.2,4,6,7,17,21–23

Structuralchanges

Aftertheresection,anincreaseintheabsorptivesurfacearea occurs,alongwithanincreaseinwallthickness,length,and diameterofthedigestivetract.2,4,10,17,23

At microstructural level, there is hypertrophy of villi, increases of microvilli and crypts, and differentiation of specialized mucosal cells.Simultaneously,local angiogene-sis is enhanced, resulting in better blood flow and tissue oxigenation.4,14,21,23–31

Motilitychanges

Thechanges ofintestinalmotility occur intwophases: an initialphaseinwhichthere isgreater motility,followedby anadaptationphase,inwhichthemotilityisreduced,thus favoring absorption. These changes are less common after amassiveresection,beingmorepronouncedinthejejunum versusileum.4,21,32,33

Functionalchanges

Asforfunctionalchanges,itshouldbementioned:

◦ Anincreaseinthenumberofcarrierproteinsandoftheir intrinsicactivity.1,2,4,10,13,23,34,35

◦ AnincreaseinthelevelsofpeptideYY.1,2,4,10,16,17,34 ◦ Anincreaseoftheenzymeactivity.4,36

Acute phase

Adaptive phase

Maintenance

phase

– Onset after resection; – Duration of 1 to 2

years;

– After the adaptive

phase;

– Permanent,

individualized

dietary

treatment;

– Effective therapy of

acute exacerbations

and optimal

maintenance therapy. – Maximum intestinal

adaptation, by

gradually increasing

exposure to nutrient (starting

by parenteral nutrition and

gradual increase

of Enteral Nutrition) – Duration of at least

4 weeks;

– Characterized by

malabsorption,

dysmotility, diarrhea and

gastric hypersecretion;

– Allows stabilization

of the patient.

Treatment

Theestablishedtreatmentoccursatanutritional, pharmaco-logicalor,ifnecessary,surgicallevel.1,19,21,37,38

Clinicaltreatment

ThepatientsinthepostoperativeperiodbeginwithPN(atleast inthefirst7–10days)asawaytoensureapropernutrition untilthereishemodynamicstabilizationwithaswitch when-everispossible,toenteralnutrition(EN)andlatertoanoral diet.4,7,9,10,21,37–40

Theestablishedplan(PNorEN),aswellasthecomposition, volumeoftheformulation,andnumberofinfusionsshouldbe adjustedtoindividualneeds.4,10,19,29,38–43However,allpatients

shouldingestsmallmealsseveraltimesaday,inorderto stim-ulatetheabsorptionofnutrients.7,38,39,43–46 Theestablished

dietshouldberichincomplexCH,essentialfattyacids(FA), andlong-chaintriglycerides(TG).Proteinshouldcorrespond to20%ofthediet.38,44–47

DietinpatientswithSBSandpreservationofthecolon

Patientswithpreservationofthecoloncanretainupto1000 extracalories/daybybacterialfermentation.38,48 Asaresult,

these patients benefit from diets rich in CH, but poor in lipids.18,38 Among the lipids inthe diet, oneshould prefer

medium-chainTGs.38

Wheneverilealresectionisgreaterthan100cm,dietsmust belowinoxalateandrichincalcium,toreducetheriskof nephrolithiasis.38,49

Solublefibershouldbeincludedinthediet,sothatthefeces arebetterformedandthatthereisanincreaseinintestinal transit.Ontheotherhand,insolublefibersarelessbeneficial, byproducingtheoppositeeffect.38,50Inascenarioofdiarrhea

>3L/day,dietswithhighlevelsofbothtypesoffibersshould beavoided.38,51

DietinpatientswithSBSandwithajejunostomyor ileostomy

Inthisgroup ofpatients, 40–50%ofdietary caloriesshould come from complex CHs and 30–40% from lipids.38,40,52 In

contrasttotheprevioussituation,medium-chainTGsshould beavoided.38,48 Solublefiberinthedietshould beincluded

accordingtotheneeds.38,44

Parenteralnutrition(PN)andIVfluids

PNshouldprovideabout20–35kcal/kg/dayandshouldconsist oflipids(20–40%,upto1g/kg/day),CHs(intheformof glu-cose,2.5–6g/kg/dayto7g/kg/day)andprotein(1.5g/kg/day). TopreventdeficiencyinessentialFAs,thesesubstancesmust

be provided,1–2% inthe formoflinoleicacid and 0.5%as linolenic␣-acid.Asforessentialaminoacids,the suplemen-tationshouldbe186mg/kg/day.7,10,38,53–55

Patientswho underwent aterminaljejunostomy require supplementationwithIVfluid,asaguaranteeofcorrect hydra-tionandforpreventionofrenalinjury.4,38Theformulations

areadministeredviasubclavianveinwithatunneledorfully implantedcatheter,inordertoreducetheriskofinfectionand thrombosis.7,38

Homeparenteralnutrition(HPN)

Inrecent decades,anewmultidisciplinaryapproachtothe treatment of these patients, HPN, was developed. Initially developedforpatientswithIF,currently,itsusewasextended topatientswithSBS.13,30,40,42,56–58

In the United States, HPN has had a growing interest, withseveralspecializedcenterswithintestinalrehabilitation programs.13,53,56 InEurope, HPN stillhas little impact, and

a prevalenceof2–40/million inhabitantsis estimated,with large variationsamongcountries.31 For various reasons,in

Portugal HPN isnotproperly established, withfew centers providing this treatment option; thus, there is a need for developmentinthisarea,withphysicians’awarenessand leg-islativechanges.56

HPNisindicatedinsituationswherepatientsrequire pro-longedPN,butwithoutrequiringhospitalization.13,17Patients

shouldbeclinicallystable,motivatedandawareofthecare theyshouldhave.Anotherimportantpointistheguarantee that thesepatientswillhavesecuredasuitablehospitalor specializedcentersupport,inadditiontoreceiving informa-tionontheformulationanditsadministrationinordertogain autonomy.13,28,38,57–60

HPNformulationsarestandardizedmixturesoffluidsand electrolytes, CHs, lipids,aminoacids, vitaminsand miner-als, availableincommercial preparations,insingle orsplit preparation.13,56

In regard to complications, in general they are usually associated withthe handling of catheter.56–59 During HPN,

mortalityismorecloselyrelatedtoanunderlyingpathology thanwiththecomplicationsinherentinthistechnique.56,58

HPNshouldbediscontinuedonceit isnolongerbenefiting the patient, or in the face ofthe magnitude ofassociated complications.58

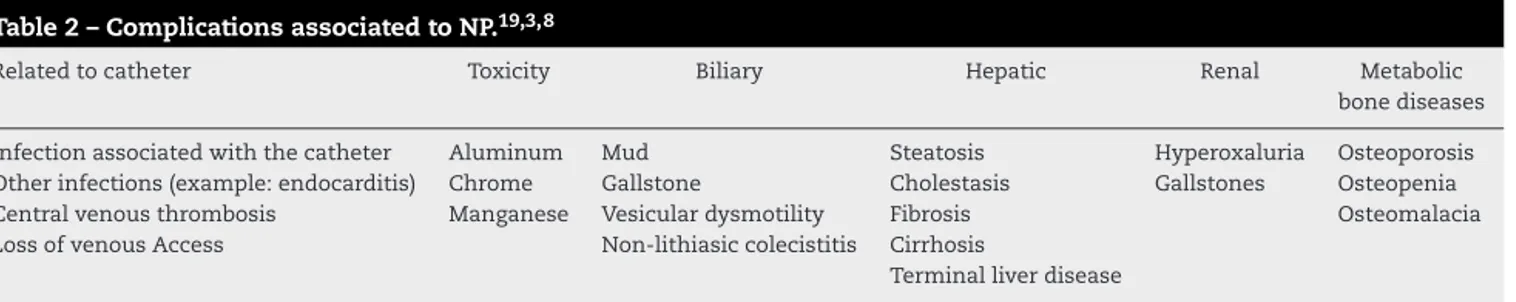

ComplicationsofaprolongedPN

Although a risky and, costly therapeutic, low morbid-ity/mortality prompts its implementation. Table2 lists the complicationsbehindaprolongedPN.19,38

Table2–ComplicationsassociatedtoNP.19,3,8

Relatedtocatheter Toxicity Biliary Hepatic Renal Metabolic

bonediseases

Infectionassociatedwiththecatheter Aluminum Mud Steatosis Hyperoxaluria Osteoporosis Otherinfections(example:endocarditis) Chrome Gallstone Cholestasis Gallstones Osteopenia

Centralvenousthrombosis Manganese Vesiculardysmotility Fibrosis Osteomalacia

LossofvenousAccess Non-lithiasiccolecistitis Cirrhosis

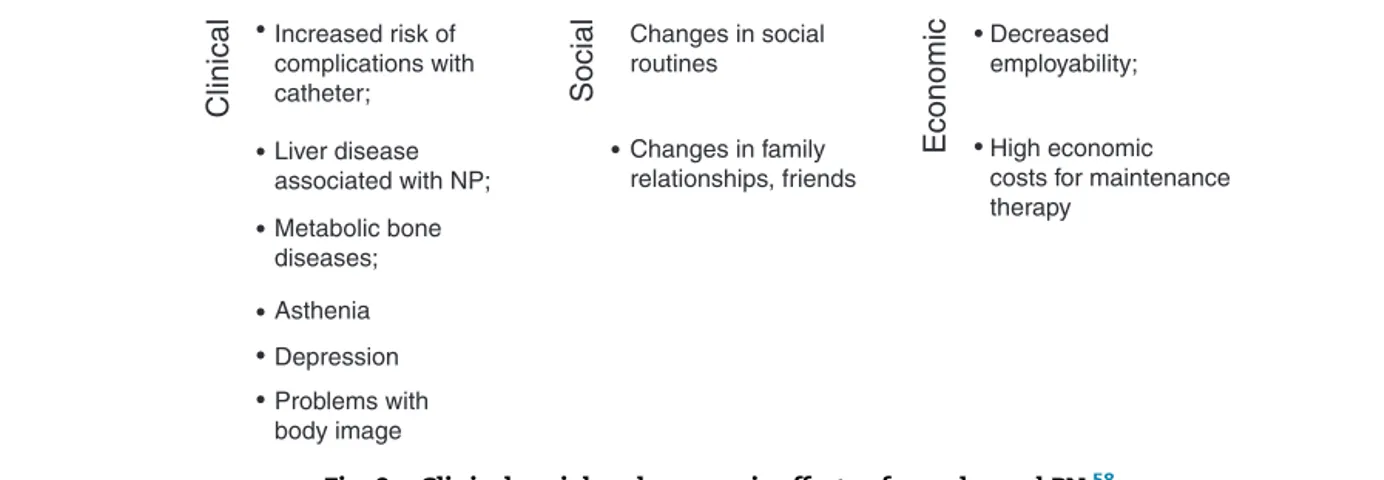

Clinical

Social

Economic

Increased risk of complications with catheter;

•

•

•

•

•

•

• •

• Changes in social

routines

Decreased employability;

High economic costs for maintenance therapy

Changes in family relationships, friends Liver disease

associated with NP;

Metabolic bone diseases;

Asthenia

Depression

Problems with body image

Fig.2–ClinicalsocialandeconomiceffectsofaprolongedPN.58

Withinthisgroup,themostcommoncomplicationsare:

Complicationsrelatedtothecatheter

In this group, infection, thrombosis, occlusion, and pneu-mothorax are included. The reported incidence is 3.6 complicationsper1000catheter-days.58,59

Septicemia

Ofallcomplicationsthisisthemostcommon,withan inci-dence of 0.5–1.6/1000 catheter-days, and isresponsible for mostcasesofmorbidityandhospitalreadmissions.The occur-renceofsepsisisanindicatorofthecareoffered.7,13,19,38,58,59

Astopredisposingfactors,oneshouldtakeintoaccountthe type/characteristicsof the catheter, its handling,13,15,28,38,56

potentialunderlyingdiseases,theanatomyoftheremaining intestine,theuseornotofthecatheterforbloodsampling, andthefrequencyofdrugadministration.28,39 Inthecaseof

recurrentinfection,onemayaddanantibiotic(p.ex., tauroli-dine)throughthecathetervalve.19,58–61Inextremesituations

and/orincaseofresistance,thecathetershouldbereplaced, butonlyasalast resort,becausethe conductshouldbeas conservativeaspossible.28,61

Catheterocclusionandcentralveinthrombosis

Venous thrombosis is a common occurrence (0.07 episodes/catheter-year),56,58,61 and the diagnosis is

estab-lished by ultrasound with doppler.28,56 This complication

occurs more frequently in patients with coagulation dis-orders, malignancies, and thrombosis of the mesenteric artery/vein;antithromboticprophylacticmeasureswith war-farin(notwithheparin,duetoanincreasedriskofinfection and ofcatheter occlusion)must beintroduced.7,10,13,28,56In

unresolvedcases,orinthosethatmayresultinsuperioror inferiorvenacavasyndrome,thecathetershouldberemoved andplacedinadifferentlocation.38

Livercomplications

Thesepatientsaresubjecttohepatobiliarydisorderssuchas steatosis,cholestasis,liverfibrosis,andcirrhosis;liverfailure anddeatharepotentialcomplications.7,19,28,38,56,58Preclinical

andclinicalevidencesuggestthatthecomponentsofPNcan behepatotoxicduetoexcesslipid,particularlywiththeuseof soyoil-basedsolutions.19,38,56,58,62

Bonemetabolicdiseases

Patients receiving PN are atgreater risk ofbonemetabolic disease (osteoporosisand osteomalacia), whose etiology is multifactorial, with an increase in incidence after bowel transplantation.7,56,58

Othercomplications

In the long term, in addition to the clinical effects, PN hassocialand economiceffectsthataffectQoLofpatients (Fig.2).15,58

ConsiderationsindiscontinuationofPN/IVfluid

Although PN is the nutrition started in the postoperative period,itisimportantthatitsdiscontinuationoccursassoon aspossible,tosafeguardintestinaladaptation.Itisestimated that, after5years discontinuation occurs in55% ofadults withSBS,anditiscriticalthepresenceofaresidualintestine withthegreatestpossiblelength,intestinalmucosawithout inflammation,acolonincontinuityandhighlevelsofplasma citrulline.13,38,63

However,priortodiscontinuationofPN,80%oftheenergy demand must betaken orally, with the occurrenceof nei-therweightlossnorchangesinthelevelsofelectrolytes.38,64

Inthissense,thephysicianmaychoosebetweentwo meth-odswiththesameunderlyingprinciple:gradualreductionof PN/IV.Inthefirstmethod,thenumberofadministrationdays isreduced,andinthesecondmethod,thevolume adminis-teredineachsessionisdecreased.Thislattermethodhasthe advantageoflessriskofdehydration.Butforbothmethods,it isimportanttoconductperiodicmonitoringandassessments ofnutritionalstatusandhydration,aswellasoflevelsof vita-minsandminerals,sothat,ifnecessary,supplementationis carriedout.38,64

Enteralnutrition(EN)

ENmustbestartedgradually,oncethehemodynamicstability isobtained,diarrhea<2L/day,andwiththeintestinal activ-ity restored, insofaras it allowstoincrease the absorptive capacity.10,18,38,47,54,56Intheirstudy,Jolyetal.27suggestedthat

continuousadministrationofnutrientsresultsinpersistent luminalstimulation.18,38

Regarding the type of enteral diet, elemental or poly-meric,theseoptionsaresimilarintermsofnutrientuptake and lossof electrolytes/fluid. However,polymeric dietsare cheaper, less hyperosmolar, improve intestinal adaptation, andare generallywell-tolerated, beingthemostfrequently administered.10,38,42

Nutritionalsupplements

Duetomalabsorption,SBSpatientsrequiresupplementation ofcertainnutrientsandmineralssuchas:

◦ Calcium (preferably citrate, thanks to increased solubility/absorption).7,17,30,38,44,65

◦ Magnesium.7,38,54,66 ◦ Iron.7

◦ Zinc.38,54,67

◦ VitaminA,B12,C,D,EandK.19,38,54,68,69

Adjuvantmedication

Theabsorptionofdrugs isalsoaltered; but whenever it is necessarytointervenepharmacologically,thedrugshouldbe administratedorally.7

Diarrheaisoneofthe symptomsdescribedand ismore intenseiftheresectionsarecarriedoutdistally.Ithasbeen foundthat patientsundergoing terminaljejunostomy have a faster intestinal transit for liquids versus patients with a preserved colon, due to reduced levels of peptide YY and glucagon-like peptide (GLP) 1 and/or 2.70 In order to

reduce intestinal motility, patients should receive lopera-mideordiphenoxylate+atropine asafirst-line medication. Theseagents havesimilarefficacy; although,somestudies haveattributed advantagetoloperamide. Asa second-line medication, codeine and opium can be considered; how-ever,consideringthattheseareCNS-actingagents,theyare less prescribed.38,70,71 These drugsshould be administered

30–60minbeforemealstoensuregreatereffectiveness.6,38,70

Another reported symptom is gastric hypersecretion, whose underlying mechanism is not yet clear, but some authorsbelievethatthisphenomenonmaybeduetotheloss ofoneormoreintestinalhormonesofgastricsecretion.4,7,24,72

Typically,thegastrichypersecretionistransitoryand disap-pearsinweekstomonthsafterresection.4,70 Astreatment,

anti-secretory drugs are administered, and the first line consists of proton pump inhibitors. But despite the good tolerability, these agents are associated with an increased riskofcommunity-acquiredpneumonia,osteoporosis,anda deficitofvitaminB12.70,72–74Amongsecond-lineagents,

his-taminetype2receptorantagonistscanbeused.6,70,72 With

regardto␣2-adrenergicagonistsandanalogsofsomatostatin, these drugs are prescribed when there is failure ofabove agents,orbecauseoftheirhighcost,routeofadministration, increasedriskoflithiasiccholecystitisanddecreased intesti-naladaptation.38,70,72

Some patients need antibiotics to control bacterial growth.15,17,39Somepreclinicalstudieshaveshownbenefitin

theuseofprebioticsorprobioticsastheseagentsincreased

intestinal adaptation, reduced bacterial translocation, and restoredtheintestinalbacterialflora.39,70,75,76

Optimizationoforalfluids

Patientswhohaveundergoneresectionsofileumorcolonare atgreaterriskofdiarrheaanddehydration,thus,itiscritical anappropriateadjustmentoffluids,particularlyinpatients undergoingterminaljejunostomyoranileostomy,wherethe electrolyteneedsaregreater(1.5–2L/day).38,49However,there

are restrictionswithrespecttowhatfluidsthe patientcan consume:hypertonicandhypotonicsolutions,diureticdrinks, caffeine,andalcoholshouldbeavoided,withpreferencegiven tooralrehydrationsolutions(ORS),astheseareformulations containingbalancedamountsofelectrolytes.4,38,52

Emergencytreatment

Severalmediatorsareconsideredaspotentialintestinotrophic factors, two of which, somatotropin and teduglutide, are currently approved for clinical use in adult patients with SBS.41,61,77

Growthhormone(GH)

GH, apituitaryhormone,hasbeenidentifiedasapotential mediatorinintestinaladaptationinconjunctionwith insulin-likegrowthfactor-1.23,38,78,79

Somatotropin,therecombinantformofGH,wasapproved in2003byFDAforthetreatmentofSBSinpatientswith nutri-tionalsupport.However,todate,EMAhasnotyetapprovedits useforthispurpose.48Therecommendeddoseis0.1mg/kg,

1×/dayfor4weeks.

InastudybyByrneetal.onPN/IV-dependentSBSpatients, the effect of somatotropin and of the optimized oral diet supplemented withglutamine inPN/IV requirements were investigated. After 4 weeks, PN decreases in volume were observed inall groups,withgreater impact onthe volume ofthedietsupplementedwithglutamineandsomatotropin. There wasalsoanincreaseintheconsumptionoforal flu-ids, to offset the PN volume reduction.63,77 In this study,

the most common adverse effects of somatotropin were identified: peripheraledema, musculoskeletal disorders,GI complaints, acute pancreatitis, impaired glucose tolerance, diabetesmellitustype2andcarpaltunnelsyndrome,aswell asitscontraindications:cancerpatients,orwithacutecritical illnessinintensivecareunits.63,77

Analogofglucagon-likepeptide-2(GLP-2)-teduglutide

GLP-2isahormoneproducedbyintestinalLcellsinresponse tointestinalstimulation,withintestinotrophiceffect;this hor-mone isimportant inthe growth and maintenanceof the intestinalepithelium.Moreover,GLP-2isassociatedwithan increasedintestinal absorption aswell asthe inhibitionof motilityandgastricsecretion.23,78,80,81

Teduglutide, the recombinant human analog of GLP-2, increases the intestinal barrier function and the abilityof intestinal absorption, and since 2012 this agent has been approved by the FDA and EMA for the treatment of PN-dependentadultpatientswithSBS.23,77,78Therecommended

AstudyconductedbyJeppesenetal.82foundthatpatients

treatedwithteduglutidedemonstratedincreasesinthesizeof villi,depthofcrypts,andofplasmalevelsofcitrulline. More-over,decreasesintheexcretionoflipids,nitrogen,sodium, potassium,andfluidsviafeceswerenoted,andconsequently, ahigherabsorptioncapacity.77,82Eveninpatientsundergoing

resectionoftheterminalileumandcolon,animprovement inintestinalabsorptioncapacityandnutritional statuswas found.83

Withregardtoadverseeffects,themostcommonhaveGI origin,beingmostintenseintheinitialperiodoftreatment.77

Animportant aspectisthat teduglutide carriesthe risk of providing an accelerated neoplastic growth; thus, a prior colonoscopyanddiscontinuationoftheiruseinpatientswith active intestinal malignancy is recommended. In patients withintestinalobstruction,biliary,pancreatic,or cardiovas-culardisease withanincreasedcardiacoutput,teduglutide shouldbeusedwithcaution.Thesamecautionshouldprevail inpatientsusing pharmaceuticalswithnarrow therapeutic margins;suchpatients shouldbemonitoredforthe riskof increasedabsorption.83

Giventhedifferencesbetweenthesetwodrugs,the deci-sion of treatment should be individualized, based on the anatomy,functionalstatusoftheremainingintestine,andthe reportedsymptoms.83

Surgicaltreatment

InpatientswithSBS,surgeryplaysanimportantrolein pre-venting,mitigatingorevenreversingIF,andoneshouldalways choosethemostconservativeapproachpossible.84,85

Surgicaloptionsarebasedonthreecategories:(1) correc-tionoftheintestinaltransit,7,84(2)improvementofintestinal

motilitywithboweldilation,84and(3)delayingtheintestinal

transitwithoutdilatationoftheintestine.84

Surgerytocorrectintestinaltransit

Rarelythese patients are presented witha slow/decreased intestinal transit; where this occurs, it is important to investigate possible partial obstructions, blind loops, and entero-entericfistulae.85

Surgeriestoimproveintestinalmotilityincasesofintestinal dilatation

Inthesmallintestineofthesepatients,oftenbacterial col-onization occurs, due to dilated segments and to a rapid intestinal transit. If these patients are refractory to medi-caltreatment,thephysicianmaychoosetoperformsurgery, which consistsofa “narrowing/bottleneckenteroplasty” in whichthedilatedportionoftheintestineisremovedthrough the extension ofthe anti-mesenteric edge. Thisprocedure isapplied when lengthofthe bowel issuitable and when the surfacearea that islost allowsabetter progressionof peristaltism.85

Insituations wherethe lengthiscritical,the Longitudi-nalIntestinalLengtheningandTailoring(LILT)technique,first describedbyBianchi,86isused.Inthisprocedure,a

bottleneck-ingoftheintestineismadewithoutlossofsurfacearea,with thecreationofalongitudinal,5-cmavascularspacealongthe

mesentericsideoftheexpandedloop.Theintestineisthen longitudinallydivided,takingcaretoperform revasculariza-tionateachside.Eachsideofthebowelisthentubularized, formingtwohemi-loopsthatconnectintheterminalregions inanisoperistalticmode. Thus,theoperationgeneratesan intestinalloopwithhalfthewidthandtwicethelength.85This

isthemostusedproceduretoincreasethesurfacearea,but itisimportanttouseitwithcautioninsituationswherethe intestineisveryshortand/orwhenthepatientsuffersfroma concomitantliverdisease.17,84–86

Another procedure is the serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP),described byKimet al.87in2003.Inthis procedure,

the lumen becomesnarrower byapplying metallic clamps perpendiculartothegreateraxisoftheintestineinazigzag pattern.84,87,88Theendresultisanincreaseinthelengthand

adecreaseofthediameteroftheintestine.Thisisaprocess lesscomplexthanthatpreviouslydescribed.24,88

Theforemostprocedureremainsunclearandvarieswith thesurgeon’spreference.However,recentstudieshaveshown better long-term results with the LILT technique in terms ofsurvival,PNautonomy,andavoidanceofintestinal trans-plantation.However,theuseoftheSTEPtechniqueismore widespread,thankstoitssimplicity.Regardingtheinherent complications,thesearemoresignificantinthecasestreated withLILT.84,89

Althoughanencouragingstep,thelong-termresultsshow thatonlyhalfofthetreatedpatientshavesustainedbeneficial resultsformorethan10years.17

Surgeriestoprolongintestinaltransitintheabsenceof intestinaldilatation

- Reversal of segments of the small intestine (RSSI): This surgeryconsistsinthecreationofantiperistalsissegments, withtheideallengthof10–12cmandmostdistallypossible (∼10cmfromtheterminalstomaorfromthejunctionofthe smallintestine-colon)toallowaretrogradeperistalsis dis-tallyandthecessationofmotilityoftheproximalintestine. Additionally,thereisthecessationofactivityofthe intrin-sicnerveplexusthatwilldelaythemyoelectricactivityof thedistalsegment.Withthisprocedureonecanreduceor evendiscontinuePN.84,89Itisimportantashortintervaltime

betweentheenterectomyandRSSI,andthatRSSI>10cm,in ordertoallowenteralautonomy.17,84

- Coloninterposition:Intheinterpositionofacolonsegment intheremainingsmallintestine(inaniso-orantiperistalsis mode),intestinaltransitisretarded,beingtheisoperistaltic trafficisthemostbeneficial.17,84

- Valvesandsphincters:Thesestructurescanbedesignedby anexternalconstrictionoftheintestine,asegmental dener-vation, or anintussusceptionofintestinalsegments (the mostcommonlyusedprocedure).Thevalvescreateapartial obstructionwhichinterruptsthenormalfunctionalpattern ofthesmallintestineandpreventretrogradereflux.17,84

Intestinaltransplant

In Portugal, the first simultaneous transplant of liver and intestinewascarriedoutattheHospitaldeCoimbrain1996.90

Table3–Contraindicationstoperformanintestinal

transplant.84

Absolute Relative

Activeinfection Reducedneurodevelopment

Malignancies Psychosocialfactors

notall patientsare able toundergo this procedure, due to contraindications(Table3).84

SomepatientswithSBSsufferfromanassociatedliver dis-ease,forwhichcertainconditions,forexample,asignificant portalhypertension,requireacombinedliver-intestine trans-plant,andalsoofthepancreasandstomachinthosepatients whereamultiorgandisorderorcompletesplenicvein throm-bosisexists.84,92

Currently,intestinaltransplantationisasuccessfulsurgery, thanks to advances in immunosuppression. However, this option should be considered at an early stage, in order to prevent the occurrence of hepatic complications, and consequently,livertransplantation,since,giventheclinical characteristicsnecessaryforitsrealization,thesepatientsare atadisadvantageversuspatientswhoonlydependonabowel transplant.84Thesurvivalratesat1yearandthepercentage

ofnon-rejectionofthegraftare89%42and79%,respectively,

afteranintestinaltransplantand72%and69%iftherewas acombinedliver-intestinetransplant.89However,thesurvival

ofpatientswithsmallboweltransplantationdecreasesinthe long term,sincethese patientshave ahigher incidenceof chronicrejectionversuspatientsundergoingacombined liver-boweltransplantation.Thiscanbeexplainedbythegreater toleranceofhepaticlymphocytescomparedtothatof intesti-nallymphocytes.84

Even considering that, currently, patients undergoing intestinaltransplantwillgetthesameresultstopatients sub-ject toa permanent PN. It is importantto note that most transplantedpatientsconsistofindividualsinwhom contin-uousmaintenanceofPNwouldresult,inthemediumterm,in amortalityrateofapproximately100%.84

Qualityoflife(QoL)

Inhealth,qualityoflifeisdescribedastheperspectivethat the patient has about his/her healthstatus, aswell ason the impact of disease and its treatment on a day-to-day basis.1,93–95

PatientswithSBSreportalowerQoL,regardlessofthe ther-apy,andQoLislowerwhenpatientsreceivePNforextended periods.1EvenpatientsonHPNorENreferamajorimpact,

notonlyataphysicalbutalsoatasociallevel.However,this subjectiveexperiencehasnotbeenproperlyevaluated, result-inginanover-estimateofthereportedvalues.1,56,94Thereare

fewstudiesreportingmeasurementswithvalidatedQoL mea-surementinstruments.Onlyin2010Baxteretal.95deviseda

specificinstrument(aprovisionalquestionnaireand psycho-metrictests)toevaluateQoLofpatientswithSBSinHPN.95

Itisimportantthattheclinicianunderstandswhatarethe goalsandexpectationsthateachpatienthasaboutthe treat-ment,aswellaswhatarethesymptomsrelatedtodiseaseorto treatmentthataremostupsettingsothatthebesttherapeutic approachcanbeprovided.1

Table4–PrognosticfactorsofSBS.4

Prognosticfactors

√Remainingintestine(sizeandlocation) √Underlying/remainingintestinalpathology √Resection/non-resectionofcolon

√Absence/presenceoftheileocecalvalve √Intestinaladaptation

√Pharmacologicaltherapy

√Nutritionalsupport(dependenceonPN/EN) √Patient(age,BMI)

√Otheraffectedorgans

Prognosis

PatientswithSBShaveareducedsurvival.19Overall,the

per-centageofsurvivalafter6yearsfromthe dateofresection is65%forpatientswitharemainingsmallintestinegreater than50cm;thispercentagedecreasesinpatientswithalength below50cm,41duetoagreaterpropensitytothedevelopment

ofrenalandliverfailure,andofdependenceonPN.4

Table4liststhefactorsassociatedwithprognosis.4

Conclusion

SBSisaconditionwithagreatvariability,bothinetiologyand initsmanifestations.1

Overtheyears,variousdevelopmentshavebeenmadein ordertoensurethebesttreatment.AlthoughPNisessential inthepostoperativeperiod,itsprolongationisassociatedwith risksandcomplicationsthatcausehighmorbidity/mortality. Inthissense,itisimportanttoensureenteralautonomyfora betterintestinaladaptation,aswellasabetterQoL.93–95

In cases where the treatment is not effective, one must opt for a surgical approach, including a intestinal transplantation.85

The last years havewitnessedthe development ofnew drugtherapies, forinstance,teduglutideand somatotropin, whichpromoteintestinalrehabilitation,improvethefunction oftheremainingbowel,andallowasignificantreductionin PNneeds.1,77,93

ToimproveQoL,thephysicianshouldeducateandmonitor patientsappropriately,sothattheirexpectationsarefullymet.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1.KellyDG,TappendenKA,WinklerMF.Shortbowelsyndrome: highlightsofpatientmanagement,qualityoflife,and survival.JParenterEnteralNutr.2014;38:427–37. 2.HöllwarthME.Reviewarticle:Shortbowelsyndrome:

pathophysiologicalandclinicalaspects.Pathophysiology. 1999;6:1–19.

4. ThompsonJS,WeswmanRA,RochlingFA,MercerDF.Current managementofshortbowelsyndrome.CurrProblSurg. 2012;49:52–115.

5. NightingaleJMD.Managementofpatientswithashortbowel. WorldJGastroenterol.2001;7:742–51.

6. ParrishCR.Theclinicalguidetoshortbowelsyndrome.Pract Gastroenterol.2005;29:67–106.

7. MalcolmKR,WilmoreDW.Shortbowelsyndrome.JPENJ ParenterEnteralNutr.2014;38:427–37.

8. BuchmanAL,ScolapioJ,FryerJ.AGAtechnicalreviewon shortbowelsyndromeandintestinaltransplantation. Gastroenterology.2003;124:1111–34.

9. BuchmanAL.Etiologyandinitialmanagementofshortbowel syndrome.Gastroenterology.2006;130:S5–15.

10.VanderhoofJA,YoungRJ.Enteralandparenteralnutritionin thecareofpatientswithshort-bowelsyndrome.BestPract ResClinGastroenterol.2003;17:997–1015.

11.BakkerH,BozzettiF,StraunM,Leon-SanzM,HebuterneX, PertkiewiczM,etal.Homeparenteralnutritioninadults:a Europeanmulticentersurveyin1997.ESPEN-HomeArtificial NutritionWorkingGroup.ClinNutr.1999;18:135–40. 12.ThompsonJS.Comparisonofmassivevsrepeatedresection

leadingtotheshortbowelsyndrome.JGastrointestSurg. 2000;4:101–4.

13.MessingB,CrennP,BeauP,Boutron-RuaultMC,Matuchansky C.Long-termsurvivalandparenteralnutrition-dependence inadultpatientswithshortbowelsyndrome.

Gastroenterology.1999;117:1043–50.

14.KellerJ,PanterH,LayerP.Managementoftheshortbowel syndromeafterextensivesmallbowelresection.BestPract ResClinGastroenterol.2004;18:977–92.

15.TappendenKA.Pathophysiologyoftheshortbowel

syndrome:considerationsofresectedandresidualanatomy.J ParenterEnterNutr.2014;38:14S–22S.

16.NightingaleJ,WoodwardJM.Guidelinesformanagementof patientswithashortbowel.Gut.2006;55:iv1–12.

17.SeetharamP,RodriguesG.Shortbowelsyndrome:areviewof managementoptions.SaudiJGastroenterol.2011;17:229–35. 18.WallsEA.Anoverviewofshortbowelsyndrome

management:adherence,adaptation,andpractical recommendations.JAcadNutrDiet.2013;113:1200–8. 19.JeppesenPB.Spectrumofshortbowelsyndromeinadults:

intestinalinsufficiencytointestinalfailure.JParenterEnteral Nutr.2014;38:8S–13S.

20.PurdunPP,KirbyDF.Short-bowelsyndrome:areviewofthe roleofnutritionsupport.JPEN.1991;15:93–101.

21. http://www.uptodate.com.sci-hub.org/contents/management-of-the-short-bowel-syndrome-in-adults

22.JeppesenPB.Thenon-surgicaltreatmentofadultpatients withshortbowelsyndrome.ExpertOpinOrphanDrugs. 2013;1:527–38.

23.TappendenKA.Intestinaladaptationfollowingresection.J ParenterEnterNutr.2014;38:23S–31S.

24.UmarS.Intestinalstemcells.CurrGastroenterolRep. 2010;12:340–8.

25.LauronenJ,PakarinenMP,KuusanmäkiP,SavilahtiE,VentoP, PaavonenT,etal.Intestinaladaptationaftermassive proximalsmall-bowelresectioninthepig.ScandJ Gastroenterol.1998;33:152–8.

26.DoldiSB.Intestinaladaptationfollowingjejuno-ilealbypass. ClinNutr.1991;10:138–45.

27.JolyF,MayeurC,MessingB,Lavergne-SloveA,Cazals-Hatlm D,NoordineML.Morphologicaladaptationwithpreserved proliferation/transportercontentinthecolonofpatientswith shortbowelsyndrome.AmJPhysiolGastrointestLiver Physiol.2009;297:G116–23.

28.O’keefeSJD,BuchmanAL,FishbeinTM.Shortbowel syndromeandintestinalfailure:consensusdefinitionsand

overview.ClinGastroenterolHepatol.2006;4: 6–10.

29.WealeAR,EdwardsAG,BaileyM,LearPA.Intestinal adaptationaftermassiveintestinalresection.PostgradMed. 2005;81:178–84.

30.ParrishCR.Theclinician’sguidetoshortbowelsyndrome. NutrIssuesGastroenterol.2005;31:67–106.

31.VanGossumA,CabreE,HébuterneX,JeppesenP,KrznaricZ, MessingB,etal.ESPENguidelinesonparenteralnutrition: gastroenterology.ClinNutr.2009;28:415–27.

32.QuigleyEM,ThompsonJS.Themotorresponsetointestinal resection:motoractivityinthecaninesmallintestine followingdistalresection.Gastroenterology.1993;105:791–8. 33.SchmidtT,PfeifferA,HackelsbergerN,WidmerR,MeiselC, KaessH.Effectofintestinalresectiononhumansmallbowel motility.Gut.1996;38:859–63.

34.NightingaleJM,KammMA,vanderSijpJR,GhateiMA,Bloom SR,Lennard-JonesJE.Gastrointestinalhormonesinshort bowelsyndrome:peptideYYmaybethe“colonicbrake”to gastricemptying.Gut.1996;39:267–72.

35.DrozdowskiL,ThomsonAB.Intestinalmucosaadaptation. WorldJGastroenterol.2006;12:4614–27.

36.BinesJE,TaylorRG,JusticeF,ParisMC,SourialM,NagyE,etal. Influenceofdietcomplexityonintestinaladaptation followingmassivesmallbowelresectioninapre-clinical model.JGastroenterolHepatol.2002;17:1170–9.

37.BuchmanAL.Shortbowelsyndrome.ClinGastroenterol Hepatol.2005;3:1066–70.

38.MatareseLE.Nutritionandfluidoptimizationforpatients withshortbowelsyndrome.JParenterEnteralNutr. 2013;37:161–70.

39.RhodaKM,ParekhNR,LennonE,Shay-DownerC,QuintiniC, SteigerE,etal.Themultidisciplinaryapproachtothecareof patientswithintestinalfailureatatertiarycarefacility.Nutr ClinPract.2010;25:183–91.

40.MatareseLE,JeppesenPB,O’keefeSJD.Shortbowelsyndrome inadults:theneedforaninterdisciplinaryapproachand coordinatedcare.JParenterEnteralNutr.2014;38:60S–4S. 41.BuchmanAL.Themedicalandthesurgicalmanagementof

shortbowelsyndrome.MedGenMed.2004;6:12.

42.Ba’athME,AlmondS,KingB,BianchiA,KhalilBA,Morabito A,etal.Shortbowelsyndrome:apracticalpathwayleadingto successfulenteralautonomy.WorldJSurg.2012;36:1044–8. 43.CrennP,MorinMC,JolyF,PenvenS,ThuillierF,MessingB.Net

digestiveabsorptionandadaptativehyperphagiainadult shortbowelpatients.Gut.2004;53:1279–86.

44.MatareseLE.Sindromedeintestinocorto:princípiosactuales detratamento.NutrEnterParenter.2012:484–96.

45.DibaiseJK,YoungRJ,VanderhoofJA.Intestinalrehabilitation andtheshortbowelsyndome:part2.AmJGastroenterol. 2004;99:1823–32.

46.MatareseLE,O’KeefeSJ,KandilHM,BondG,CostaG, Abu-ElmagdK.Shortbowelsyndrome:clinicalguidelinesfor nutritionmanagement.NutrClinPract.2005;20:493–502. 47.JeppesenPB,HoyCE,MontersenPB.Deficienciesofessential

fattyacids,vitaminAandEandchangesinplasma lipoproteinsinpatientswithreducedfatabsorptionor intestinalfailure.EurJClinNutr.2000;54:632–42. 48.JeppersenPB,MortensenPB.Theinfluenceofapreserved

colonontheabsorptionofmediumchainfatinpatientswith smallbowelresection.Gut.1998;43:478–83.

49.MatareseLE,SteigerE.Dietaryandmedicalmanagementof shortbowelsyndromeinadultpatient.JClinGastroenterol. 2006;40:S85–93.

substrate,althoughpectinsupplementationmaymodestly enhanceshortchainfattyacidproductionandfluid absorption.JPENJParenterEnteralNutr.2011;35: 229–40.

51.ByrneTA,VegliaL,CarmelioM,BennettH.Beyondthe prescription:optimizingthedietofpatientswithshortbowel syndrome.NutrClinPract.2000;15:306–11.

52.CompherC,WinklerM,BoullataJI.Nutritionalmanagement ofshortbowelsyndrome.ClinNutrSurgPatients.

2008;2:148–53.

53.CoberMP,RobinsonC,AdamsD.AmericanSocietyfor ParenteralandEnteralNutritionBoardofDirectors. Guidelinesfortheuseofparenteralandenteralnutritionin adultandpediatricpatients.JPENJParenterEnteralNutr. 2002;26:SA-138.

54.LochsH,DejongC,HammarqvistF,HebuterneX,Leon-Sanz M,SchutzT,etal.ESPENguidelinesonenteralnutrition: gastroenterology.ClinNutr.2006;25:260–74.

55.O’keefeSJ,PetersonME,FlemingCR.Octreotideasanadjunct tohomeparenteralnutritioninthemanagementof

permanentend-jejunostomysyndrome.JPENJParenter EnteralNutr.1994;18:26–34.

56.PintoJFGM,CostaEL.Nutric¸ãoparentéricadomiciliária:a mudanc¸adeumparadigma.ArqMed.2015;29:103–11. 57.AlmeidaMTL.OpapeldoSuporteNutricionalnodomicílio.

FCNAUP–Trabalhoacadémico;2002.

58.WinklerMF.Clinical,socialandeconomicimpactsofhome parenteralnutritiondependenceinshortbowelsyndrome.J ParenterEnteralNutr.2014;38:32S–7S.

59.GillandersL,AngstmannK,BallP,O’CallaghanM,Thomson A,WongT,etal.Aprospectivestudyofcatheter-related complicationsinHPNpatients.ClinNutr.2012;31:30–4. 60.JohnBK,KhanMA,SpeerhasR,RhodaK,HamiltonC,

DechiccoR,etal.Ethanollocktherapyinreducing catheter-relatedbloodstreaminfectionsinadulthome parenteralnutritionpatients:resultsofaretrospectivestudy. JPENJParenterEnteralNutr.2012;36:603–10.

61.Al-AminAH,SarveswaranJ,WoodJM,BurkeDA,Donnellan CF.Efficacyoftaurolidineonthepreventionof

catheter-relatedblood-streaminfectionsinpatientsonhome parenteralnutrition.JVascAcess.2013;14:379–82.

62.XuZW,LiYS.Pathogenesisandtreatmentofparenteral nutrition-associatedliverdisease.HepatobiliaryPancreatDis Int.2012;11:586–93.

63.CrennP,Coudray-LucasC,ThuillierF,CynoberL,MessingB. Postabsorptiveplasmacitrullineconcentrationisamarkerof absorptiveenterocytemassandintestinalfailureinhumans. Gastroenterology.2000;119:1496–505.

64.DiBaiseJK,MatareseLE,MessingB,SteigerE.Strategiesfor parenteralnutritionweaninginadultpatientswithshort bowelsyndrome.JClinGastroenterol.2006;40:S94–8. 65.HanzlikRP,FlwlerSC,FisherDH.Relativebioavailabilityof

calciumfromcalciumformate,calciumcitrate,andcalcium carbonate.JPharmacolExpTher.2005;313:1217–22.

66.BragaCBM,FerreiraIML,MarchiniJS,CunhaSFC.Copperand magnesiumdeficienciesinpatientswithshortbowel syndromereceivingparenteralnutritionororalfeeding.Arq Gastroenterol.2015;52:94–9.

67.AroraR,KulshreshthaS,MohanG,SinghM,SharmaP. Estimationofserumzincandcopperinchildrenwithacute diarrhea.BiolTraxeElemRes.2006;114:121–6.

68.OkudaK.DiscoveryofvitaminB12intheliverandits absorptionfactorinthestomach:ahistoricalreview.J GastroenterolHepatol.1999;14:301–8.

69.JeejeebhoyKN.Managementofshortbowelsyndrome: avoidanceoftotalparenteralnutrition.Gastroenterology. 2006;130:S60–6.

70.KumpfVJ.Pharmacologicalmanagementofdiarrheain patientswithshortbowelsyndrome.JParenterEnterNutr. 2014,http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0148607113520618. 71.ChanL-N.Opioidanalgesicsandthegastrointestinaltract.

PractGastroenterol.2008;32:37–50.

72.ThomsonAB,SauveMD,KassamN,KamitakaharaH.Safety ofthelongtermuseofprotonpumpinhibitors.WorldJ Gastroenterol.2010;16:2323–30.

73.LamJR,SchneiderJL,ZhaoW,CorleyDA.Protonpump inhibitorandhistamine2receptorantagonistuseand vitaminB12deficiency.JAMA.2013;310:2435–42.

74.JeppesenPB,StaunM,TjellesenL,MortensenPB.Effectof intravenousranitidineandomeprazoleonintestinal absorptionofwater,sodium,andmacronutrientsinpatients withintestinalresection.Gut.1998;43:763–9.

75.MogilnerJG,SrugoI,LurieM,ShaoulR,CoranAG,ShiloniE, etal.Effectsofprobioticsonintestinalregrowthandbacterial translocationaftermassivesmallbowelresectioninarat.J PediatrSurg.2007;42:1365–71.

76.ReddyVS,PatoleSK,RaoS.Roleofprobioticsinshortbowel syndromeininfantsandchildren–asystematicreview. Nutrients.2013;5:669–79.

77.JeppesenPB.Pharmacologicaloptionsforintestinal rehabilitationinpatientswithshortbowelsyndrome.J ParenterEnterNutr.2014;38:45S–52S.

78.AltersSE,McLaughlinB,SpinkB,LachinyanT,WangCW, PodustV,etal.GLP-2-“G-XTEN:apharmaceuticalprotein withimprovedserumhalf-lifeandefficacyinaratCrohn’s diseasemodel”.PLoSONE.2012;7:e50630.

79.McMellenME,WakemanD,LongshoreSW,McDuffieLA, WarnerBW.Growthfators:possiblerolesforclinical managementoftheshortbowelsyndrome.SeminPediatr Surg.2010;19:35–43.

80.JeppesenPB,HartmannB,ThulesenJ,GraffJ,LohmannJ, HansenBS,etal.Glucagon-likepeptide2improvesnutrient absorptionandnutritionalstatusinshortbowelpatientswith nocolon.Gastroenterology.2001;120:806–15.

81.LjungmannK,HartmannB,Kissmeyer-NielsenP,FlyvbjergA, HolstJJ,LaurbergS.Time-dependentintestinaladaptation andGLP-2alterationsaftersmallbowelresectioninrats.AmJ PhysiolGastrointestLiverPhysiol.2001;281:G779–85.

82.JeppesenPB,PertkiewiczM,MessingB,IyerK,SeidnerDL, O’keefeSJ,etal.Teduglutidereducesneedforparenteral supportamongpatientswithintestinalfailure.

Gastroenterology.2012;143:1473–81.

83.O’KeefeSJ,JeppesenPB,GilroyR,PertkiewiczM,AllardJP, MessingB.Safetyandefficacyofteduglutideafter52weeksof treatmentinpatientswithshortbowelsyndrome-intestinal failure.ClinGastroenterolHepatol.2013;11:815–23.

84.FishbeinTM.Intestinaltransplantation.NEnglJMed. 2009;361:998–1008.

85.KishoreRI.Surgicalmanagementofshortbowelsyndrome.J ParenterEnterNutr.2014;20:1–7.

86.BianchiA.Longitudinalintestinallengtheningandtailoring: resultsin20children.JRSocMed.1997;90:429–32.

87.KimHB,FauzaD,GarzaJ,OhJT,NurkoS,JaksicT.Serial transverseenteroplasty(STEP):anovelbowellengthening procedure.JPediatrSurg.2003;38:425–9.

88.PakarinenMP,KurvinenA,KoivusaloAI,IberT,RintalaRJ. Long-termcontrolledoutcomesafterautologousintestinal reconstrutionsurgeryintreatmentofsevereshortbowel syndrome.JPediatrSurg.2013;48:339–44.

89.BaxterJP,FayersPM,MckinlayAW.Areviewofthequalityof adultpatientstreatedwithlong-termparenteralnutrition. ClinNutr.2006;25:543–53.

91.RegeAS,SudanDL.Autologousgastrointestinal

reconstruction:reviewoftheoptimalnontransplantsurgical optionsforadultsandchildrenwithshortbowelsyndrome. NutrClinPract.2012;28:65–74.

92.JonesBA,HullMA,KimHB.Autologousintestinal reconstrutionsurgery.SeminPediatrSurg.2010;19: 59–67.

93.JeppesenPB,PertkiewiczM,ForbesA,PironiL,GabeSM,JolyF, etal.Qualityoflifeinpatientswithshortbowelsyndrome treatedwiththenewgluxagon-likepeptide-2analogue

teduglutide–analysesfromarandomised,placebocontrolled study.ClinNutr.2013;32:713–21.

94.BerghöferP,FragkosKC,BaxterJP,ForbesA,JolyF,HeinzeH, etal.Developmentandvalidationofthedisease-specific ShortBowelSyndrome–QualityofLife(SBS-QoLTM)scale.

ClinNutr.2013;32:789–96.