1226 Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics - October-December 2015 - Volume 11 - Issue 4

Primary cardiac lymphoblastic B‑cell

lymphoma: Should we treat more

intensively?

ABSTRACT

Primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL) is a rare neoplasm, the majority of cases of which are non‑Hodgkin’s, diffuse large B‑cell (DLBCL). We report the first case of an adult with PCL B‑cell lymphoblastic lymphoma whose disease evolution was grim. A 52‑year‑old male reported dyspnea and facial swelling lasting for 4 months and upon a physical examination he presented bradycardia, jugular venous engorgement, and hypophonesis of cardiac sounds. An electrocardiography (Echo) revealed a right atrial mass and nodules at the pericardium. The patient was treated with R‑Hyper‑CVAD (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone) and presented very short remission. At this time, we used R‑ICE (rituximab plus ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide) chemotherapy and the patient underwent complete remission after two courses and received autologous bone marrow transplantation (auto‑BMT). After 75 days of follow‑up, the patient reported dyspnea and a new Echo showed a recurrence of the disease. The patient died due to cardiac failure. PCL is a rare disease with an unfavorable prognosis and a prompt diagnosis and treatment are fundamental to survival. We believe that more intensive therapies, such as auto‑BMT, should be considered as a first treatment option.

KEY WORDS: B‑cell, lymphoblastic lymphoma, primary cardiac lymphoma, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL) is a rare neoplasm, the majority of cases of which are non‑Hodgkin’s, diffuse large B‑cell (DLBCL) involving the pericardium, right atrium, and right ventricle.[1‑4] PCL is detected in 1–3% of cardiac tumors, representing less than 0.5% of extranodal lymphomas.[3,4] These rarely reported cases demonstrate involvement of the right heart, in contrast to myxoma, which typically involves the left atrium.[1,3,4]

A prompt diagnosis of PCL is important to achieve a complete response and is fundamental to favorable evolution of the disease.[2‑7] A diagnosis is often difficult since PCL manifests symptoms consistent with other cardiopulmonary disorders. Many patients report dyspnea for months before diagnosis and this delay decreases the chance of curing the disease.[2‑7]

The aim of this report is to present, to the best of our knowledge, the first case of an adult with PCL B‑cell lymphoblastic lymphoma whose disease evolution was grim. We reviewed the reported cases of the last 10 years; evaluating the clinical presentation, evolution, and response to the treatment.

CASE REPORT

A 52‑year‑old male reported dyspneaand facial swelling lasting for 4 months. Upon a physical examination, he presented bradycardia, jugular venous engorgement, and hypophonesis of cardiac sounds. An electrocardiography (Echo) revealed sinus bradycardia. The Echo also revealed a right atrial mass and nodules at the pericardium. The patient underwent a biopsy of his nodules in the pericardium/myocardium [Figure 1a and b] and a diagnosis of B lymphoblastic lymphoma (CD20 (+), CD79a (+), TdT (+), CD3 (−), and CD5 (−)) was established (World Health Organization). Positron emission tomography‑CT (PET‑CT) showed a markedly increased fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake across the pericardium/myocardium without uptake in other lymph nodes [Figure 1a and b].

The patient was treated with R‑Hyper‑CVAD course A (rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and dexamethasone) and course B (high dose of methotrexate and cytarabine) plus rituximab. After the second course of chemotherapy, the patient exhibited a complete remission according to an Echo, but the disease progressed shortly after the third course. An Echo demonstrated once again revealed nodules at

Access this article online

Website: www.cancerjournal.net

DOI: 10.4103/0973-1482.154063 PMID: ***

Quick Response Code:

E-JCRT Correspondence

Luiz Ivando Pires Ferreira Filho, Howard Lopes Ribeiro Junior, Edílson Diógenes Pinheiro Júnior1,

Ronald Feitosa Pinheiro

Post‑Graduate Program in Medical Science, Department of Clinical Medicine, Federal University of Ceara, Fortaleza, 1Health Sciences Center, University of Fortaleza, Fortaleza, Ceara, Brazil

For correspondence:

Dr. Ronald Feitosa Pinheiro,

R. Pereira Valente, 738, Meireles, 60160250, Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. E‑mail:

Filho, et al.: Primary B‑LBL of the heart

1227

Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics - October-December 2015 - Volume 11 - Issue 4 the pericardium/myocardium. At this time, we used R‑ICE

chemotherapy, a combination of rituximab plus ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide. The patient underwent complete remission after two courses and received autologous bone marrow transplantation (auto‑BMT). After 75 days of follow‑up, the patient reported dyspnea and a new Echo showed a recurrence of the disease. The patient died due to cardiac failure.

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of PCL is extremely rare. Recently, Cresti et al.,[8] evaluated the incidence of primary cardiac tumors in a 14‑year population study. The researchers detected 1.38 cases per year in 100,000 individuals. The most commonly detected tumors were myxoma, fibroelastoma, lipoma, rhabdomyoma, hemangioma, sarcoma, and lymphoma, representing 48, 15, 15, 8, 5, 5, and 2% of cases, respectively. Davis et al.,[9] also studied the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) experience with primary pediatric cardiac malignancies. They detected an age‑adjusted incidence of 0.00686 per 100,000 individuals in the United States. The most common subtype was soft sarcoma, followed by non‑Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

To the best of our knowledge, the case studied here is the first report of an adult with primary cardiac B‑cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. This disorder is highly aggressive with a predominance of T‑cell lineage and commonly presents a bulky anterior mediastinal mass, pleural effusion, or organomegaly.[10] After reviewing the literature, we detected only one case of primary B‑Cell lymphoblastic lymphoma.[11] The case was a 10‑year‑old child who presented with fatigue, syncope, and vomiting for 2 weeks before diagnosis.[11] The most common subtype of PCL is DLBCL,[2‑13] which is detected in

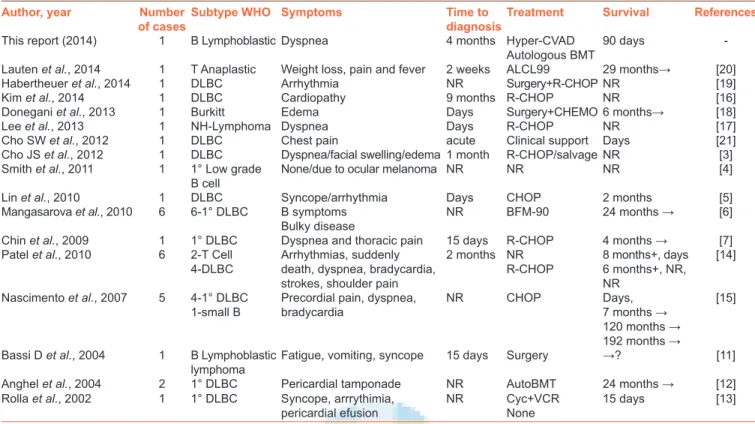

more than 50% of cardiac lymphomas, followed by low‑grade B cell lymphoma [Table 1].

The majority of patients with PCL present symptoms related to cardiac frequency or difficulty breathing.[2‑6] Dyspnea is the most common symptom that may be related to pleural effusion.[2‑3,7,19,20] Patients occasionally report a history of several months of progressive fatigue, night sweats, and weight loss before their diagnosis. We detected a case with a 9‑month delay prior to diagnosis.[21] Our patient reported progressive dyspnea for 4 months before diagnosis. Arrhythmias and syncope are commonly detected.[11,19,20] The most common arrhythmias are atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, and bradycardia [Table 1].[19,20] Our patient presented with sinus bradycardia which was related to the involvement of the right atrium. The sinoatrial node (located in the right atrium) is the natural pacemaker that initiates impulses for the heartbeat; if it is blocked by lymph nodes, its normal function can be disrupted. As cases of arrhythmia are evaluated, an Echo must always be performed. If the Echo demonstrates any mass in the right atrial, the chance of lymphoma increases because atrial myxoma typically involves the left atrium.[19,20] Of utmost importance, we also detected two patients who were initially diagnosed as having hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, but after biopsy were diagnosed as non‑Hodgkin’s lymphoma.[16,21]

The majority of patients have been treated with CHOP/ R‑CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisone) with variable response[2,5‑7,19] and many cases present very short (less than one month) survival durations[2,19] with conventional chemotherapy [Table 1].[6,19,20] Long‑term survivalis observed when patients were treated with more intensive therapy as Berlin‑Frankfurt‑Munster (BFM), anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL 99), and auto‑BMT: 24, 29, and 24 months, respectively. Unfortunately, our patient exhibited a quick recurrence of the disease after auto‑BMT. We suggest that intensive therapies, including BFM, ALCL 99, and auto‑BMT, should be considered as a first line for treatment of patients with more extensive cardiac involvement, such as biatrial and biventricular involvement.

Surgery should not be considered the only treatment. Non‑Hodgkin’s lymphoma is a systemic disorder and chemotherapy should always be used as treatment. We detected patients who were treated with surgery out of necessity of maintaining cardiac function, but the best results were reported when chemotherapy was added as an adjunct to surgery.[17,18]

Sometimes, surgery is not an option of treatment because the myocardium is too rigid due to tumor invasion of the pericardium and myocardium. Modern imaging modalities, including Magnetic Resonance Imaging ( MRI), may help to determine the extent of tumor involvement in the heart. Surgery for mass reduction is not usually recommended because it does not seem to improve the prognosis.[7] The most Figure 1: (a) Lymphoblastic lymphoma showing an extensive number

of nodules in the pericardium/myocardium. (b and c) PET‑CT showed a markedly increased FDG uptake across the pericardium/myocardium without uptake in other lymph nodes. The arrow indicates the nodules PET‑CT = Positron emission tomography‑computed tomography,

FDG = luorodeoxyglucose c b

a

Filho, et al.: Primary B‑LBL of the heart

1228 Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics - October-December 2015 - Volume 11 - Issue 4 common approach is pericardiocentesis, which is performed

urgently to remove pericardial effusion.[7,10,15] Literature review did not reveal any PCL treated with radiotherapy . This modality of treatment is likely dangerous to the heart due to increased chance of arrhythmias and fibrosis of pericardium.

PCL is a disease with an unfavorable prognosis.[2,5,19,20] Many patients present symptoms related to cardiac frequency, especially arrhythmias or difficulty in breathing and a prompt diagnosis and treatment are fundamental to survival. Many cases present very short survival durations with conventional chemotherapy (CHOP/R‑CHOP) and we believe that more intensive therapies, such as auto‑BMT, should be considered as a first treatment option.

REFERENC ES

1. Abdullah HN, Nowalid WK. Infiltrative cardiac lymphoma with tricuspid valve involvement in a young man. World J Cardiol 2014;6:77‑80. 2. Soens L, Schoors D, Van Camp G. Acute heart failure due to fulminant

myocardial infiltration by a diffuse large B‑cell lymphoma. Acta Cardiol 2012;67:101‑4.

3. Cho JS, Her SH, Park MW, Kim HD, Baek JH, Youn HJ, et al. A butterfly‑shaped primary cardiac lymphoma that showed bi‑atrial involvement. Korean Circ J 2012;42:46‑9.

4. Smith M, Golwala H, Magharyous H, Trotter T, Sawh R, Lozano P. Right atrial B‑cell lymphoma in a patient with ocular melanoma. J Card Surg 2011;26:625‑8.

5. Lin JN. Cardiaclymphoma with first manifestation of recurrent syncope‑a case report and literature review. Int Med Case Rep J 2010;10:1‑6.

6. Mangasarova IA, Magomedova AU, Kravchenko SK, Zvonkov EE, Kremenetskaia AM, Vorob’ev VI, et al. Diffuse large B‑cell lymphoma with primary involvement of mediastinal lymph nodes: Diagnosis and treatment. Ter Arkh 2010;82:61‑5.

7. Chin JY, Chung MH, Kim JJ, Lee JH, Kim JH, Maeng IH, et al. Extensive primary cardiac lymphoma diagnosed by percutaneous endomyocardial biopsy. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2009;17:141‑4. 8. Cresti A, Chiavarelli M, Glauber M, Tanganelli P, Scalese M, Cesareo F,

et al. Incidence rate of primary cardiac tumors: A 14‑year population study. J Cardiovasc Med 2014.

9. Davis JS, Allan BJ, Perez EA, Neville HL, Sola JE. Primary pediatric cardiac malignancies: The SEER experience. Pediatr Surg Int 2013;29:425‑9. 10. Thomas DA, O’Brien S, Cortes J, Giles FJ, Faderl S, Verstovsek S, et al.

Outcome with the hyper‑CVAD regimens in lymphoblastic lymphoma. Blood 2004;104:1624‑30.

11. Bassi D, Lentzner BJ, Mosca RS, Alobeid B. Primary cardiac precursor B lymphoblastic lymphoma in a child: A case report and review of the literature. Cardiovasc Pathol 2004;13:116‑9.

12. Anghel G, Zoli V, Petti N, Remotti D, Feccia M, Pino P, et al. Primary cardiac lymphoma: Report of two cases occurring in immunocompetent subjects. Leukemia Lymphoma 2004;45:781‑8. 13. Rolla G, Bertero MT, Pastena G, Tartaglia N, Corradi F, Casabona R,

et al. Primary lymphoma of the heart. A case report and review of the literature. Leuk Res 2002;26:117‑20.

14. Cho SW, Kim BK, Hwang JT, Kim JH, Kim BO, Goh CW, et al. A case of primary cardiaclymphoma mimicking acute coronary and aortic syndrome. Korean Circ J 2012;42:776‑80.

15. Lauten M, Vieth S, Hart C, Wössmann W, Tröger B, Härtel C, et al. Table 1: Reported cases of patients with primary cardiac lymphoma with clinical presentation, time to diagnosis, response to treatment and survival

Author, year Number of cases

Subtype WHO Symptoms Time to diagnosis

Treatment Survival References

This report (2014) 1 B Lymphoblastic Dyspnea 4 months Hyper‑CVAD

Autologous BMT

90 days ‑

Lauten et al., 2014 1 T Anaplastic Weight loss, pain and fever 2 weeks ALCL99 29 months→ [20]

Habertheuer et al., 2014 1 DLBC Arrhythmia NR Surgery+R‑CHOP NR [19]

Kim et al., 2014 1 DLBC Cardiopathy 9 months R‑CHOP NR [16]

Donegani et al., 2013 1 Burkitt Edema Days Surgery+CHEMO6 months→ [18]

Lee et al., 2013 1 NH‑Lymphoma Dyspnea Days R‑CHOP NR [17]

Cho SW et al., 2012 1 DLBC Chest pain acute Clinical support Days [21]

Cho JS et al., 2012 1 DLBC Dyspnea/facial swelling/edema 1 month R‑CHOP/salvage NR [3]

Smith et al., 2011 1 1° Low grade

B cell

None/due to ocular melanoma NR NR NR [4]

Lin et al., 2010 1 DLBC Syncope/arrhythmia Days CHOP 2 months [5]

Mangasarova et al., 2010 6 6‑1° DLBC B symptoms Bulky disease

NR BFM‑90 24 months → [6]

Chin et al., 2009 1 1° DLBC Dyspnea and thoracic pain 15 days R‑CHOP 4 months → [7]

Patel et al., 2010 6 2‑T Cell

4‑DLBC

Arrhythmias, suddenly death, dyspnea, bradycardia, strokes, shoulder pain

2 months NR R‑CHOP

8 months+, days 6 months+, NR, NR

[14]

Nascimento et al., 2007 5 4‑1° DLBC 1‑small B

Precordial pain, dyspnea, bradycardia

NR CHOP Days,

7 months → 120 months → 192 months →

[15]

Bassi D et al., 2004 1 B Lymphoblastic lymphoma

Fatigue, vomiting, syncope 15 days Surgery →? [11]

Anghel et al., 2004 2 1° DLBC Pericardial tamponade NR AutoBMT 24 months → [12]

Rolla et al., 2002 1 1° DLBC Syncope, arrrythimia,

pericardial efusion

NR Cyc+VCR

None

15 days [13]

Legend. 1°=Primary, 2°=Secondary, ALCL=Anaplastic large‑cell lymphoma, BFM=Berlin‑Frankfurt‑Munich group, BMT=Bone Marrow Transplantation, CHEMO=Chemotherapy, CHOP=Cyclophosphamide, Hydroxydaunorubicin, Oncovin and Prednisone, CVAD=Cyclophosphamide, Vincristine, Doxorubicin and Dexamethasone, Cyc=cyclofosmamide, DLBC=Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma, NH=Non‑Hodgkin’s, NR=Not reported, R‑CHOP=CHOP+rituximab,

VCR=Vincristine, → = Alive, WHO=World Health Organisation

Filho, et al.: Primary B‑LBL of the heart

1229

Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics - October-December 2015 - Volume 11 - Issue 4 Cardiac anaplastic large cell lymphoma in an 8‑year old boy. Leuk

Res Rep 2014;3:36‑7.

16. Lee GY, Kim WS, Ko YH, Choi JO, Jeon ES. Primary cardiaclymphoma mimicking infiltrative cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:589‑91. 17. Habertheuer A, Ehrlich M, Wiedemann D, Mora B, Rath C, Kocher A.

A rare case of primary cardiac B cell lymphoma. J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;9:14.

18. Donegani E, Ambassa JC, Mvondo C, Giamberti A, Ramponi A, Palicelli A, et al. Primary cardiac Burkitt lymphoma in an African child. G Ital Cardiol 2013;14:481‑4.

19. Patel J, Melly L, Sheppard MN. Primary cardiac lymphoma: B‑ and T‑cell cases at a specialist UK centre. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1041‑5.

20. Nascimento AF, Winters GL, Pinkus GS. Primary cardiac lymphoma: Clinical, histologic, immunophenotypic, and genotypic features of 5 cases of a rare disorder. Am J Surg Pathol 2007;31:1344‑50 21. Kim DH, Kim YH, Song WH, Ahn JC. Primary cardiaclymphoma

presenting as an atypical type of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Echocardiography 2014;31:E115‑9.

Cite this article as: Pires Ferreira Filho LI, Ribeiro HL, Pinheiro ED, Pinheiro RF. Primary cardiac lymphoblastic B‑cell lymphoma: Should we

treat more intensively?. J Can Res Ther 2015;11:1034.

Source of Support: Nil, Conlict of Interest: None declared.