w w w . r b h h . o r g

Revista

Brasileira

de

Hematologia

e

Hemoterapia

Brazilian

Journal

of

Hematology

and

Hemotherapy

Original

article

Oral

health-related

quality

of

life

of

children

and

teens

with

sickle

cell

disease

Maria

Luiza

da

Matta

Felisberto

Fernandes

a,∗,

Ichiro

Kawachi

b,

Alexandre

Moreira

Fernandes

a,

Patrícia

Corrêa-Faria

a,

Saul

Martins

Paiva

a,

Isabela

Almeida

Pordeus

aaUniversidadeFederaldeMinasGerais(UFMG),BeloHorizonte,MG,Brazil bHarvardSchoolofPublicHealth,Boston,UnitedStates

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received24June2015 Accepted19January2016 Availableonline13February2016

Keywords:

Sicklecell Qualityoflife Child Oralhealth Malocclusion

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Background:Childrenwithsicklecelldiseasemayhavetheirqualityoflifeaffectedbyoral alterations.However,thereisstilllittledataonoralhealth-relatedqualityoflifeinthese children.Theaimofthisstudywastoinvestigatetheinfluenceofsicklecelldisease, socio-economiccharacteristics,andoralconditionsonoralhealth-relatedqualityoflifeofchildren andteens.

Method:Onehundredandsixchildrenandteenswithsicklecelldiseasewerecompared toasimilarsampleof385healthypeers.Datawerecollectedthroughoralexaminations, interviewstoassessqualityoflife(ChildPerceptionsQuestionnaireforchildrenaged8–10 and11–14)andquestionnairescontainingquestionsonsocioeconomicstatus.

Results:TherewerenostatisticallysignificantdifferencesinthetotalscoresoftheChild PerceptionsQuestionnairesordomainscorescomparingsicklecelldiseasepatientsto con-trolsubjects.Whensub-scaleswerecompared,oralsymptomsandfunctionallimitations hadagreaternegativeimpactonthequalityoflifeofadolescentswithsicklecelldisease (p-value<0.001andp-value<0.01,respectively)whencomparedtohealthycontrols.The onlystatisticallysignificantdeterminantsofnegativeimpactonoralhealth-relatedquality oflifeintheoverallsamplewashomeovercrowding(morethantwopeople/room)inthe youngerchildren’sgroup,anddentalmalocclusionamongteens.

Conclusion:Therewasnosignificantdifferenceinthenegativeimpactontheoral health-relatedqualityoflifebetweenthegroupwithsicklecelldiseaseandthecontrolgroup.Ofthe oralalterations,therewasasignificantdifferenceintheoralhealth-relatedqualityoflife betweenadolescentswithsicklecelldiseaseandcontrolsonlyinrelationtomalocclusion. Amongthesocioeconomiccharacteristics,onlyovercrowdingwassignificantlyassociated withanegativeimpactonoralhealth-relatedqualityoflife.

©2016Associac¸ãoBrasileiradeHematologia,HemoterapiaeTerapiaCelular.Published byElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

∗ Correspondingauthorat:FaculdadedeOdontologia,UniversidadeFederaldeMinasGerais(UFMG),Av.AntônioCarlos,6627,Campus

Universitário,31270-901BeloHorizonte,MG,Brazil.

E-mailaddress:marialuizadamatta@gmail.com(M.L.daMattaFelisbertoFernandes). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjhh.2016.01.004

Introduction

Sicklecelldisease(SCD)isaninheritedautosomalrecessive blooddisease.Theinheritanceofonesicklecell genefrom eachparent(SS)isthemostcommonandtheseverestformof thedisease,affectingaround280,000newbornsperyear.This disease,inadditiontothalassemia,isresponsiblefor3.4%of alldeathsofchildrenunderfiveyearsofage.1Eachyear,3500 childreninBrazilarebornwithSCD.2

ChildrenwithSCDareatriskforseriousmorbiditiesrelated tovascular occlusion, hemolysis, and infection, whichcan impairtheirqualityoflife(QoL)andleadtoearlydeath.The pathologicaleffectsofSCD,seeninmineralizedconnective tis-sues,alsooccurindentaltissuesandtheoralcavity,usually inlatechildhoodand duringadolescence.3 Themost com-monlydescribed findings inthe oral cavity,which are not pathognomonicbutmaybecharacteristicofthedisease,are palloroftheoralmucosaduetoalowhematocritand depapil-lated tongue.4 Thereare reportsofdelayed tooth eruption, hypoplasiaand hypomineralization,hypercementosis, pulp stonesandasymptomaticpulpnecrosisduetothrombosisin thebloodvessels.5–7

IndividualswithSCD experience alower QoL compared tohealthypeers.8,9 Duetotheclinicalcourseofthedisease, SCDisthoughttoaffecttheQoLinmultipledimensions.The mostseriousorganicchangesresultinemotionaland physi-calstressforchildrenandtheirfamilies.10Thefrequencyof episodesoffever,hospitalizations,andpaincantriggeranger andsadness.11Moreover,lowerhealth-relatedQoLinchildren withSCDisassociatedwithasocioeconomicdisadvantage,12 alowlevel ofeducationand notlivingwithbothbiological parents.13 Religionand spirituality have been identified by individualswithSCDasanimportantfactorincopingwith stressandindeterminingtheQoL.14

QoLmay beaffected byoralconditions.Oralconditions suchasdental cariesandmalocclusions affectself-esteem, theabilitytochewand speak,and maybeassociatedwith absenteeism from school and psychological problems.15,16 AlthoughtherehavebeenstudiesontheQoLofpatientswith hematological diseaseswith regardto theirbehavioral and psychologicalimpacts,emphasisonoralhealthhasremained relativelyunderexplored.Onlyrecently,theoralhealth-related QoL(OHRQoL) of54 teenagers with SCD was evaluated by anadolescentmedicineclinicinColumbus,Ohio,comparing themwithadolescentswithotherchronicdiseases.Therewas nostatisticallysignificantdifferenceintheOHRQoLbetween thetwogroups.17

Theobjective ofthisstudy was toinvestigate the influ-enceofSCDandfactorsrelatedtothedisease,oralconditions, resources and individual characteristics on the OHRQoL of childrenwiththisdisease.

Methods

Ethicalapproval

ThisstudyreceivedapprovalfromtheEthicsCommitteesof theFundac¸ão deHematologiaeHemoterapia doEstadode MinasGerais(Hemominas)andtheUniversidadeFederalde

MinasGerais(UFMG),Brazil.Writteninformedconsentwas obtainedfrom the participantsor parents/guardians ofthe participants ofthis study.This research was conductedin accordancewiththeHelsinkiDeclarationasrevisedin2008.

Participantsandrecruitment

ThestudywasconductedinthecityofBeloHorizonte,the cap-italofthestateofMinasGerais,SoutheastBrazil.Thestudy samplewas madeupofchildrenwithSCD,residing inthe metropolitanregionofBeloHorizonte,agedfrom8to14years old,sampledfromthepatientregistryofthereferralcenter, Hemominas.Acontrolgroupofhealthychildrenandteens was recruitedfrom thesame schoolsattended bythe chil-drenwithSCD.Atotalof450childrenandadolescentswith SCDaged8–14yearswereregisteredasreceivingservicesfrom Hemominasin2012.Amongthese,196childrenandteenagers residedinthemetropolitanregionofBeloHorizonte.18

Thesamplesizewascalculatedfromtheexpectedstandard deviations(SDs)oftheQoLscales toevaluatethe OHRQoL: the Child PerceptionsQuestionnaire forchildrenaged8–10 (CPQ8–10) (SD=10.7) and 11–14 years (CPQ11–14) (SD=10.1) investigatedinapilotstudy.Thepilotstudywasconducted usingarandomsampleof34childrenand35teenswithSCD registered in Hemominas. Therequired samplesize (n=51 childrenaged8–10years,and n=45adolescentsaged11–14 years)wascalculatedbasedontheabilitytodetectafive-point differenceinQoLscoresoncomparingSCDpatientsto appar-entlyhealthycontrols,assumingan˛=0.05andˇ=0.10.The programSPSSversion20.0wasusedforallstatisticalanalyses. Onehundredandeightyhealthyadolescentsand205healthy youngerchildrenwhowereenrolledatthesameschoolsand in the same classes asthose with SCDwere selected, and matchedbyageandgender.Theoptiontomatchonecase toatleasteverythreecontrolswasbecausehealthycontrols couldbelessmotivatedtoparticipatethanindividualsina health-caresetting.19

EligibilitycriteriaforinclusionintheSCDgroupwereas follows:diagnosisofSCDhemoglobin(Hb)SSintheirmedical records,notsufferingfromapainfulcrisisatthetimeofthe survey,nomedicalconditionsotherthanSCD,noemergency dentalappointmentwithinthepreviousthreemonthsandno intellectualdisability.Eligibilityofthemembersofthecontrol groupincluded:noorganic,physiological,orpsychiatric dis-ordersandnointellectualdisability,apparentlyhealthywith nodentalappointmentwithinthepreviousthreemonths.

Calibrationexercise

k=0.92;dentalcaries:k=0.92;gingivalbleeding:k=0.91).The test–retestofinstrumentswasalsocarriedout.Atthisstage, theparticipantsansweredtheappropriateinstrumentforage (CPQ8–10orCPQ11–14)intwosessionsatanintervalofninedays. Theagreementvalue obtainedforbothinstruments was a Kappa=0.82.

Clinicaloralexamination

DentalexaminationsofpatientswithSCDwereperformedat Hemominasandhealthycontrolswereexaminedinschools.A qualifieddentistperformedanintra-oralexamoneachpatient usingadisposablemirror,communityperiodontalindex(CPI) probesandgauzes.TheWorldHealthOrganization(WHO)20 normswereusedtoevaluatethefollowing:theDecayed, Miss-ingandFilledTeethindex(DMFT),theDentalAestheticindex (DAI)andtheGingivalindex.TheDAIidentifiesclinicaland aesthetic componentsand mathematicallyderives a single score.Thisscorehasbeenfoundtobesignificantly associ-atedwiththeperceptionoftreatmentneededbystudentsand parents.20Theresearchteamwasmadeupofonedentistand fourtrainedandcertifieddentalresearchers.

Non-clinicalexamination

Through interviews with parents, information was gath-eredonsocioeconomicaspects,religiosity(never,sometimes, frequently), race (White,Black, other),children living with bothparentsandmedicalinformation(diseaseseverity,age atdiagnosis of SCD). Thefollowing socioeconomic aspects wereevaluated:homeovercrowding(numberofpeople/room), yearsofschoolingofthemotherandfather,houseownership, carownership,familyincome(US$/month).

Oralhealth-relatedqualityoflifeinstrument

TheBrazilianversionoftheChildPerceptionsQuestionnaires (CPQ)forchildrenaged8–10 years(CPQ8–10)21 and for chil-drenaged11–14years (CPQ11–14)21 were usedtoassess the OHRQoL.Thesequestionnairesweretranslatedandvalidated fortheBrazilianpopulation, and provedtohave good psy-chometric properties. The CPQ8–10 contains 25 questions21 and the short version of the CPQ11–1422 contains 16 ques-tions.Theinstrumentsencompassfourhealthdomains:oral symptoms,functionallimitations,emotionalwell-being,and social well-being related to oral health conditions. These aretwo ofthe fourquestionnairescomprisingtheOHRQoL measures developed by Jokovic et al.23 All items consider the frequency of events in relation to the condition of the mouth andteeth overthe previous threemonths. The responses to questions were scored on a frequency scale usingthefollowingresponseoptionsandassociatedcodes: ‘Never=0’; ‘Once/twice=1’; ‘Sometimes=2’; Often=3’, and ‘Everyday/Almosteveryday=4’.Thequestionnairesalso con-tained two single-item global ratings. The CPQ sub-scale scoreswere calculated bysumming responses. Theoverall CPQ8–10score,whichmayrangefrom0to100,andtheoverall CPQ11–14score,whichmayrangefrom0to64,wasthesumof

alldomainscores.Higherscorestranslatetoagreaternegative OHRQoL.

Statisticalanalysis

Descriptive and univariate analyses were performed sepa-ratelyfortheoverallsample(SCDandhealthychildrenand adolescents)andonlyforSCDpatients(childrenand adoles-cents).Theresponsestocategoricalquestionsbyeachgroup werecomparedusingeithertheChi-squaretestortheFisher’s exact test for contingency tables with small cell counts. ThenonparametricMann–Whitneytestwasusedtocompare mediansofcontinuousvariablesbetweentheSCDand con-trolgroups.Theage,genderandschoollocation,whichwere recordedatthetimeoftheinterview,werecontrolledinthe multivariablelinearregressionanalysesofOHRQoL.

Results

Excellentinter-raterreliabilitywasfoundfortheoralexams: Kappa value=0.89 (inter-examiner) and Kappa value=0.92 (intra-examiner).Thecorrelationofresponsestointerviews was alsotested (Kappa value=0.82). Theagreementin the recalibration ofclinicalexams,whichwascarriedout every twomonths,consistentlyachievedaKappavalue≥0.87.

The response rate was 100% in both case and control groups.IntheSCDgroup,therewere106participants:56 chil-dren(31boysand25girls)withanaverageageof8.9(SD=0.87) yearsand50teens(30boysand20girls)withanaverageageof 12(SD=1.08)years.Therewere385individualsinthecontrol group.Inthisgroup,therewere205children(112boysand93 girls)withanaverageageof8.9(SD=0.8)yearsand180 ado-lescents(106boysand 74girls)withanaverageageof11.9 (SD=1.0)years.

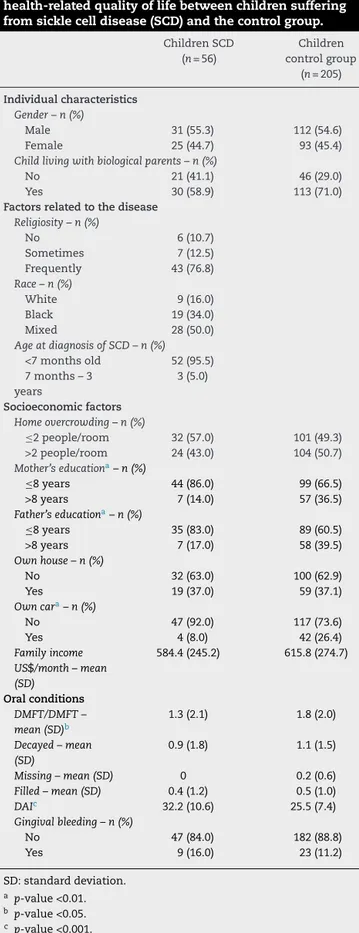

Inthegroupofchildren(Table1),bothmaternaland pater-naleducationallevelswerelowerintheSCDgroup(p-value <0.001and<0.01respectively).MorechildrenwithSCDcame from homeswithnocar(p-value<0.01).Malocclusion(DAI) was worse inchildrenwithSCD (p-value <0.001).However, dentalcaries(DMFT)weremoreprevalentinthechildrenin thecontrolgroup(p-value<0.05).Inthegroupofchildren(aged 8–10years),therewerenostatisticaldifferencesintotalscores oftheCPQ8–10ordomainscoreswhenSCDindividualswere comparedtocontrolsubjects(Table2).

Table1–Descriptiveandcomparativeanalysisof individualcharacteristics,factorsrelatedtothedisease, resources,oralconditions,andnegativeimpactonoral health-relatedqualityoflifebetweenchildrensuffering fromsicklecelldisease(SCD)andthecontrolgroup.

ChildrenSCD (n=56)

Children controlgroup

(n=205)

Individualcharacteristics Gender–n(%)

Male 31(55.3) 112(54.6) Female 25(44.7) 93(45.4)

Childlivingwithbiologicalparents–n(%)

No 21(41.1) 46(29.0)

Yes 30(58.9) 113(71.0)

Factorsrelatedtothedisease Religiosity–n(%)

No 6(10.7)

Sometimes 7(12.5) Frequently 43(76.8)

Race–n(%)

White 9(16.0)

Black 19(34.0) Mixed 28(50.0)

AgeatdiagnosisofSCD–n(%)

<7monthsold 52(95.5) 7months–3

years

3(5.0)

Socioeconomicfactors Homeovercrowding–n(%)

≤2people/room 32(57.0) 101(49.3) >2people/room 24(43.0) 104(50.7)

Mother’seducationa–n(%)

≤8years 44(86.0) 99(66.5)

>8years 7(14.0) 57(36.5)

Father’seducationa–n(%)

≤8years 35(83.0) 89(60.5)

>8years 7(17.0) 58(39.5)

Ownhouse–n(%)

No 32(63.0) 100(62.9)

Yes 19(37.0) 59(37.1)

Owncara–n(%)

No 47(92.0) 117(73.6)

Yes 4(8.0) 42(26.4)

Familyincome US$/month–mean (SD)

584.4(245.2) 615.8(274.7)

Oralconditions

DMFT/DMFT– mean(SD)b

1.3(2.1) 1.8(2.0)

Decayed–mean (SD)

0.9(1.8) 1.1(1.5)

Missing–mean(SD) 0 0.2(0.6)

Filled–mean(SD) 0.4(1.2) 0.5(1.0)

DAIc 32.2(10.6) 25.5(7.4)

Gingivalbleeding–n(%)

No 47(84.0) 182(88.8)

Yes 9(16.0) 23(11.2)

SD:standarddeviation.

a p-value<0.01.

b p-value<0.05.

c p-value<0.001.

Table2–TheChildPerceptionsQuestionnairesubscales for8to10-year-oldsicklecelldisease(SCD)childrenand controls(CPQ8–10).

Maximum score

ChildrenSCD (n=56) Mean(SD)

Childrencontrol group(n=205)

Mean(SD)

ScoreCPQ8-10 100 14.5(12) 17.9(15) Oralsymptoms 20 5.5(3.6) 5.9(3.8) Functionallimitation 20 2.8(3.1) 3.5(4.7) Emotionalwell-being 20 3.3(4.5) 3.9(4.7) Socialwell-being 40 2.9(3.6) 4.6(6.2)

SD:standarddeviation.

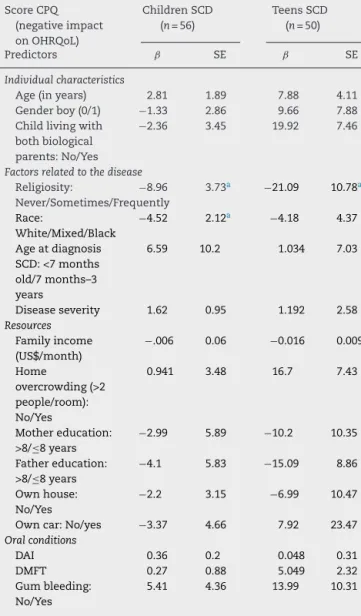

Tables5and6showtheresultsofmultivariable-adjusted linearregression.Table5showstheresultsofcombined anal-yses ofSCD patientsandhealthycontrols.Inbothyounger childrenandadolescents,adiagnosisofSCDwasnot associ-atedwithanegativeimpactonOHRQoL.Theonlystatistically significantdeterminants(p-value<0.05)ofanegativeimpact on OHRQoL inthe overall samplewas home overcrowding (morethantwopeople/room)fortheyoungerchildren’sgroup, anddentalmalocclusion(DAI)amongteens.

Table6presents the findingsrestricted toSCD patients, stratified by age group. Among the younger children, the onlyfactorsthatweresignificantlyassociatedwithanegative impactontheOHRQoLwerereligiosityandrace(withBlack peoplehavingahigherQoL).Noclinicalfactorswere associ-atedwithanegativeimpactontheOHRQoLinthegroupof teenswithSCD;theonlyfactorrelatedtoanegativeimpact ontheOHRQoLwasreligiosity,thefrequencyofchurch atten-dance(p-value<0.05).Livingwithbothbiologicalparentswas marginallyassociatedwithanegativeimpactontheOHRQoL, butinanunexpecteddirection;childrenlivingwithonlyone parentreportedhigherQoL(p-value=0.056).

Discussion

In this study, an overall negative impact of SCD on the OHRQoLwasnotfound.Clinicaldentalcharacteristicssuch asahistoryofgingivalbleedingandexperiencewithcaries did not adverselyaffect the OHRQoL with the only excep-tionbeingmalocclusion(DAI)amongadolescents.Themain determinantoftheOHRQoLwasasocioeconomicfactor(home overcrowding).

Table3–Descriptiveandcomparativeanalysisof individualcharacteristics,factorsrelatedtothedisease, resources,oralconditions,andnegativeimpactonoral health-relatedqualityoflifebetweenteenagerssuffering fromsicklecelldisease(SCD)andthecontrolgroup.

TeensSCD (n=50)

Teens control-group

(n=180)

Individualcharacteristics Gender–n(%)

Male 30(60.0) 106(58.9)

Female 20(40.0) 74(41.1)

Childlivingwithbiologicalparentsa–n(%)

No 30(73.0) 56(38.9)

Yes 11(27.0) 88(61.1)

Factorsrelatedtothedisease

Religiosity(frequentchurch)–n(%)

Never 9(18.0)

Sometimes 14(28.0)

Frequently 27(54.0)

Race–n(%)

White 6(12.0)

Black 19(38.0)

Mixed 25(50.0)

AgeatdiagnosisofSCD–n(%)

<7monthsold 47(94.0)

7months–3years 3(6.0)

Socio-economicfactors

Homeovercrowding–n(%)

<2people/room 25(64.0) 90(62.0)

>2people/room 14(36.0) 55(38.0)

Mother’seducationa–n(%)

≤8years 22(58.0) 132(91.7)

>8years 16(42.0) 12(8.3)

Father’seducationa–n(%)

≤8years 14(61.0) 120(83.3)

>8years 9(39.0) 24(16.7)

Ownhouse–n(%)

No 31(76.0) 91(85.9)

Yes 10(24.0) 53(14.1)

Owncar–n(%)

No 40(98.0) 128(88.9)

Yes 2(1.0) 18(11.1)

Familyincome US$/month (mean±SD)a

1463(671) 628(257)

Oralconditions

DMFT/DMFT–mean (SD)b

1.5(1.9) 2.1(2.8)

Decayed–mean(SD) 1.0(1.4) 1.0(1.7)

Missing–mean(SD) 0.1(0.6) 0.2(0.7)

Filled–mean(SD) 0.4(0.8) 0.8(1.7)

DAI 32(10.3) 29.2(10.6)

Gingivalbleedinga–n(%)

No 23(46.0) 152(84.4)

Yes 27(54.0) 28(15.6)

SD:standarddeviation.

a p-value<0.001.

b p-value<0.05.

Inthisstudy,SCDchildrenandadolescentsdidnothave a more negative overall profileof QoL when compared to thecontrolgroup.Althoughthisfindingissomewhat unex-pected,itagreeswithpreviouslyreportedresults.18Thereason giveninthepreviousstudywasthatthecontrolgroupalso

Table4–TheChildPerceptionsQuestionnairesubscales for11to14-year-oldsicklecelldisease(SCD)teensand controls(CPQ11–14).

Domains–CPQ11–14 Totalpossible

score

SCDteens (n=50) Media(SD)

Control teens (n=180) Media(SD)

Oralsymptoms 16a 5.38(3.40) 4.89(2.82)

Functionallimitations 16b 4.68(3.62) 3.33(2.96)

Emotionalwell-being 16 3.22(3.23) 3.71(3.95)

Socialwell-being 16 2.78(3.49) 2.52(3.43)

OverallCPQ11-14 64 16.06(11.65) 14.37(9.73)

SD:standarddeviation.

a p-value<0.001.

b p-value<0.01.

Table5–Betacoefficientsofthenegativeimpactonthe oralhealth-relatedqualityoflife(OHRQoL)inchildren andteenswithsicklecelldisease(SCD)andcontrol groupbyindividualcharacteristics,factorsrelatedtothe disease,resources,andoralconditions.

CPQscore (negative impacton OHRQoL)

Children SCD(n=56) Controls(n=205)

Teens SCD(n=50) Controls(n=205)

Predictors ˇ SE ˇ SE

Individualcharacteristics

Age(inyears) −1.35 1.2 −0.64 0.83 Genderboy

(0/1)

0.197 2.03 2.34 1.72

Childliving withboth biological parents: No-0/Yes-1

−3.36 2.54 2.31 1.94

Factorsrelatedtothedisease

SCD(0/1) −4.80 2.60 −2.41 3.69

Resources

Familyincome (US$/month)

0.004 0.004 0.003 0.89

Home overcrowding (>2

people/room): No/Yes

9.56 2.51a 2.26 1.73

Mother education: >8/≤8years

−1.33 2.43 −0.156 2.75

Father education: >8/≤8years

−0.474 2.4 −3.05 2.27

Ownhouse: No/Yes

0.629 2.46 −0.09 1.81

Owncar: No/Yes

0.302 2.65 2.61 1.15

Oralconditions

DAI 0.128 0.148 0.165 0.08*

DMFT 0.133 0.57 0.57 0.04

Gumbleeding: No-0/Yes-1

0.4 2.83 0.88 2.03

CPQ: Child Perceptions Questionnaire; ˇ: beta coefficient; SE: standarderror.

Table6–Betacoefficientsofthescorewithanegative impactonoralhealth-relatedqualityoflife(OHRQoL)in childrenandteenssufferingfromsicklecelldisease (SCD)byindividualcharacteristics,factorsrelatedtothe disease,resources,andoralconditions.

ScoreCPQ (negativeimpact onOHRQoL)

ChildrenSCD (n=56)

TeensSCD (n=50)

Predictors ˇ SE ˇ SE

Individualcharacteristics

Age(inyears) 2.81 1.89 7.88 4.11 Genderboy(0/1) −1.33 2.86 9.66 7.88 Childlivingwith

bothbiological parents:No/Yes

−2.36 3.45 19.92 7.46

Factorsrelatedtothedisease

Religiosity:

Never/Sometimes/Frequently

−8.96 3.73a −21.09 10.78a

Race:

White/Mixed/Black

−4.52 2.12a −4.18 4.37

Ageatdiagnosis SCD:<7months old/7months–3 years

6.59 10.2 1.034 7.03

Diseaseseverity 1.62 0.95 1.192 2.58

Resources

Familyincome (US$/month)

−.006 0.06 −0.016 0.009

Home

overcrowding(>2 people/room): No/Yes

0.941 3.48 16.7 7.43

Mothereducation: >8/≤8years

−2.99 5.89 −10.2 10.35

Fathereducation: >8/≤8years

−4.1 5.83 −15.09 8.86

Ownhouse: No/Yes

−2.2 3.15 −6.99 10.47

Owncar:No/yes −3.37 4.66 7.92 23.47

Oralconditions

DAI 0.36 0.2 0.048 0.31

DMFT 0.27 0.88 5.049 2.32

Gumbleeding: No/Yes

5.41 4.36 13.99 10.31

CPQ: Child Perceptions Questionnaire; ˇ: beta coefficient; SE: standarderror.

a p-value<0.05.

sufferedfromchronicdiseases.Incontrast,thecontrolgroup ofthisstudywascomposedstrictlyofapparentlyhealthy chil-drenandadolescents.Aninterpretationofthisfindingisthat childrenandadolescentswithSCDareresilient,andthatthey adjustpsychologically totheir condition. Indeed,the main determinantsofOHRQoLinthisstudywerebackground socio-economiccircumstances(homeovercrowding),religiosity,and aestheticconcerns(malocclusion)amongteens.

Socioeconomic disadvantage impacts QoL by making accesstohealthcaremoredifficult.12 Accordingtoastudy conductedwithaconvenience sampleofAfrican-American children with SCD, the OHRQL was correlated to family income.9Incontrast,asignificantassociationbetween socio-economicvariablesandOHRQLinchildrenwithSCDwasnot observedin this study. Thisresult may bejustified bythe

accesstomedicalmonitoring,aswellastotreatmentatthe SCDhealthcenter.Monitoringandtreatmentresultsinbetter healthcareandconsequentlylessimpactontheOHRQL.

Theresults showthat practicing a religionisprotective in maintaining the OHRQoL in both children and adoles-centswithSCD.Religionandspiritualityhavebeenpreviously reportedbyindividualswithSCD asanimportantfactorin copingwithstressandindeterminingQoL.29,30Involvement inareligionisanimportantmeansofindividualcoping,as wellasameansofreceivingsocialsupportfromothers.31

Comparisonsbetweenthefindingsobtainedinthisstudy and other studiesneedtobeviewedwithadegree of cau-tionasmostofthesestudiesarebasedonsmall,convenience samplesrecruitedinclinicalsettings.Although population-basedstudiescanandhavebeenusedtocomparetheimpact ofcommonconditionssuchasdentaldecay,malocclusionand gingivalbleedinginrandomsamplesofchildren,SCDisnotas prevalentandrecruitmentfromtheclinicsinwhichtheyare treatedremainstheonlyfeasibleoption.Moreover,this cross-sectionaldesigncannotaddressthetrajectoriesofQoLover timeandacrossthelifecourseofSCDpatients.Further stud-ieswithlongitudinalfollow-upofpatientsareneeded.Theuse ofOHRQoLshouldbeconsideredanimportanttoolinthe clini-calpractice,andaninvaluableguidetoassessthepsychosocial functioningofyoungpatientsaffectedwithSCD.

Therewasnosignificantdifferenceinnegativeimpacton OHRQoL between the SCD and controlgroups. Ofthe oral alterations,therewasasignificantdifferenceintheOHRQoL betweenadolescentswithSCDandcontrolsonlyinrelationto malocclusion.Amongthesocioeconomiccharacteristics,only overcrowdingwassignificantlyassociatedwiththenegative impactonOHRQoL.

Funding

This study received supportfrom the National Councilfor ScientificandTechnologicalDevelopment(CNPq),Ministryof ScienceandTechnology,theStateofMinasGeraisResearch Foundation (FAPEMIG), Brazil, and the Lemann Institute, Brazil.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgment

TheauthorswouldliketothankHemominas.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1.HankisJ.Towardhighqualitymedicalcareforsicklecell disease:arewethereyet?JPediatr.2010;86(4):256–8. 2.Brasil,MinistériodaSaúde.ManualdeEducac¸ãoemSaúde:

3. RazmusTF,FotosPG.Oralmedicineinclinicaldentistry: hematologicdisorders.Compendium.1987;8(3):214,216-8, 221-2.

4. FrancoBM,Gonc¸alvesJC,SantosCR.Manifestac¸õesbucaisda anemiafalciformeesuasimplicac¸õesnoatendimento odontológico.ArqOdontol.2007;43(3):92–6.

5. OnyeasoCO,daCostaOO.Dentalaestheticsassessedagainst orthodontictreatmentcomplexityandneedinNigerian patientswithsickle-cellanemia.SpecCareDentist. 2009;29(6):249–53.

6. OlivieriNF,PakbazZ,VichinskyE.HbE/beta-thalassaemia:a commonandclinicallydiversedisorder.IndianJMedRes. 2011;134(4):522–31.

7. LunaAC,RodriguesMJ,MenezesVA,MarquesKM,SantosFA. Cariesprevalenceandsocioeconomicfactorsinchildrenwith sicklecellanemia.BrazOralRes.2012;26(1):43–9.

8. BarakatLP,PattersonCA,DanielLC,DampierC.Qualityoflife amongadolescentswithsicklecelldisease:mediationofpain byinternalizingsymptomsandparentingstress.HealthQual LifeOutcomes.2008;6:60.

9. PanepintoJA,PajewskiNM,FoersterLM,SabnisS,Hoffmann RG.Impactoffamilyincomeandsicklecelldiseaseonthe health-relatedqualityoflifeofchildren.QualLifeRes. 2009;18(1):5–13.

10.CaseyRL,BrownRT.Psychologicalaspectsofhematologic diseases.ChildAdolescPsychiatrClinNAm.

2003;12(3):567–84.

11.MahdiN,Al-OlaK,KhalekNA,AlmawiWY.Depression, anxiety,andstresscomorbiditiesinsicklecellanemia patientswithvaso-occlusivecrisis.JPediatrHematolOncol. 2010;32(5):345–9.

12.PalermoTM,SchwartzL,DrotarD,McGowanK.Parental reportofhealth-relatedqualityoflifeinchildrenwithsickle celldisease.JBehavMed.2002;25(3):269–83.

13.LockerD,JokovicA,StephensM,KennyD,TompsonB,Guyatt G.Familyimpactofchildoralandoro-facialconditions. CommunityDentOralEpidemiol.2002;30(6):438–48. 14.HarrisonMO,EdwardsCL,KoenigHG,BosworthHB,Decastro

L,WoodM.Religiosity/spiritualityandpaininpatientswith sicklecelldisease.JNervMentDis.2005;193(4):

250–7.

15.PeresKG,CascaesAM,LeãoAT,CôrtesMI,VettoreMV. Sociodemographicandclinicalaspectsofqualityoflife relatedtooralhealthinadolescents.RevSaudePublica. 2013;47(3):19–28.

16.SchuchHS,DosSantosCostaF,TorrianiDD,DemarcoFF, GoettemsML.Oralhealth-relatedqualityoflifeof

schoolchildren:impactofclinicalandpsychosocialvariables. IntJPaediatrDent.2015;25(5):358–65.

17.RalstromE,daFonsecaAM,RhodesM,AminiH.Theimpact ofsicklecelldiseaseonoralhealth-relatedqualityoflife. PediatrDent.2014;36(1):24–8.

18.Hemominas.PlanoDiretorEstadualdeSanguee Hemoderivados;2012.Availablefrom:http://www. hemominas.mg.gov.br[cited12.09.14].

19.Marcos-PintoR,Diniz-RibeiroM,CarneiroF,MachadoJC, FigueiredoC,ReisCA,etal.Firstdegreerelativesandfamilial aggregationofgastriccancer:whotochooseforcontrolin case-controlstudies?FamCancer.2012;11(1):137–43. 20.WorldHealthOrganization.OralHealthSurveys:basic

methods.4thed.Geneva:WorldHealthOrganization;1997. Availablefrom:http://www2.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/ 2009/OH stEsurv.pdf[cited12.09.14,Internet].

21.MartinsMT,FerreiraFM,OliveiraAC,PaivaSM,ValeMP, AllisonPJ,etal.PreliminaryvalidationoftheBrazilianversion ofthechildPerceptionsQuestionnaire8–10.EurJPaediatr Dent.2009;10(3):135–40.

22.GoursandD,PaivaSM,ZarzarPM,Ramos-JorgeML,

CornacchiaGM,PordeusIA,etal.Cross-culturaladaptationof theChildPerceptionsQuestionnaire11–14(CPQ11–14)forthe BrazilianPortugueselanguage.HealthQualLifeOutcomes. 2008;6:2.

23.JokovicA,LockerD,StephensM,KennyD,TompsonB,Guyatt G.Validityandreliabilityofaquestionnaireformeasuring childoral-health-relatedqualityoflife.JDentRes. 2002;81(7):459–63.

24.TaylorLB,NowakAJ,GillerRH,CasamassimoPS.Sicklecell anemia:reviewofthedentalconcernsandaretrospective studyofdentalandbonychanges.SpecCareDentist. 1995;15(1):38–42.

25.JavedF,CorreaFO,NoohN,AlmasK,RomanosGE,Al-Hezaimi K.Orofacialmanifestationsinpatientswithsicklecell disease.AmJMedSci.2013;345(3):234–7.

26.daCostaOO,KehindeMO,IbidapoMO.Occlusalfeaturesof sicklecellanemiapatientsinLagos,Nigeria.NigerPostgrad MedJ.2005;12(2):121–4.

27.SouzaKC,DamiãoJJ,SiqueiraKS,SantosLC,SantosMR. Acompanhamentonutricionaldecrianc¸aportadorade anemiafalciformenaRededeAtenc¸ãoBásicadeSaúde.Rev PaulPediatr.2008;26(4):400–4.

28.CostaCP,CarvalhoHL,ThomazEB,SousaSF.Craniofacial boneabnormalitiesandmalocclusioninindividualswith sicklecellanemia:acriticalreviewoftheliterature.RevBras HematolHemoter.2012;34(1):60–3.

29.GeorgeLK,LarsonDB,KoenigHG,McCullonghME. Spiritualityandhealth:whatweknow,whatweneedto know.JSocClinPsychol.2000;19(1):102–16.

30.McCulloughME,HoytWT,LarsonDB,KoenigHG,ThoresenC. Religiousinvolvementandmortality:ameta-analyticreview. HealthPsychol.2000;19(3):211–22.