w w w . r b h h . o r g

Revista

Brasileira

de

Hematologia

e

Hemoterapia

Brazilian

Journal

of

Hematology

and

Hemotherapy

Special

article

Guidelines

on

neonatal

screening

and

painful

vaso-occlusive

crisis

in

sickle

cell

disease:

Associac¸ão

Brasileira

de

Hematologia,

Hemoterapia

e

Terapia

Celular

Project

guidelines:

Associac¸ão

Médica

Brasileira

–

2016

Josefina

Aparecida

Pellegrini

Braga

a,

Mônica

Pinheiro

de

Almeida

Veríssimo

b,

Sara

Teresinha

Olalla

Saad

c,

Rodolfo

Delfini

Canc¸ado

d,e,

Sandra

Regina

Loggetto

f,∗aEscolaPaulistadeMedicina,UniversidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo(Unifesp),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil bCentroInfantilBoldrini,Campinas,SP,Brazil

cFaculdadedeCiênciasMédicas,UniversidadeEstadualdeCampinas(Unicamp),Campinas,SP,Brazil dFaculdadedeCiênciasMédicasdaSantaCasadeSãoPaulo(FCMSCSP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil eHospitalSamaritano,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

fCentrodeHematologiadeSãoPaulo(CHSP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received12February2016

Accepted4April2016

Availableonline8April2016

Introduction

Theguidelines projectisajoint initiative ofthe Associac¸ão

MédicaBrasileiraandtheConselhoFederaldeMedicina.Itaims

to bring together information in medicine to standardize

conductinordertohelpdecision-makingduringtreatment.

The data contained in this article were prepared by and

∗ Correspondingauthorat:AvenidaBrigadeiroLuísAntônio,2533,JardimAmérica,01401-000SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil.

E-mailaddress:loggetto.sr@hotmail.com(S.R.Loggetto).

are recommended by the Associac¸ão Brasileira de

Hematolo-gia,HemoterapiaeTerapiaCelular(ABHH).Evenso,allpossible

medical approaches should be evaluated by the physician

responsiblefortreatmentdependingonthepatient’s

charac-teristicsandclinicalstatus.

Thisarticlepresentstheguidelinesonneonatalscreening

andpainfulvaso-occlusivecrisisinsicklecelldisease(SCD).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjhh.2016.04.001

1516-8484/©2016Associac¸ãoBrasileiradeHematologia,HemoterapiaeTerapiaCelular.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisan

Description

of

the

method

used

to

gather

evidence

TheseGuidelineswerepreparedbyelaboratingeightclinically

relevantquestions,tworelatedtoneonatalscreeningforSCD

andsixrelated topainfulvaso-occlusive crisisinSCD. The

questionswere structuredusingthe Patient/Problem,

Inter-vention,ComparisonandOutcome(PICO)system(Appendix

A),allowingthegenerationofevidencesearchstrategiesin

the key scientific databases (MEDLINE PubMed, Lilacs,

Sci-ELO, Embase, CochraneLibrary, Premedline via OVID). The

datarecoveredwerecriticallyanalyzedusingdiscriminatory

instruments(scores)accordingtothetypeofevidence–JADAD

forrandomizedclinicaltrialsandtheNewcastleOttawascale

for non-randomized studies.After identifying studies that

potentially substantiaterecommendations,thelevel of

evi-denceanddegreeofrecommendationwerecalculatedusing

theOxfordClassification.1

Degree

of

recommendation

and

level

of

evidence

A:Majorexperimentalandobservationalstudies

B:Minorexperimentalandobservationalstudies

C:Casereports(non-controlledstudies)

D:Opinionwithoutcriticalevaluationbasedonconsensus,

physiologicalstudiesoranimalmodels

Background

SCDisagroupofinheriteddiseasesinwhichthesynthesisof

hemoglobin(Hb)isimpairedbecauseofamutationinthebeta

globinchainoftheHbgeneonchromosome16.This

muta-tionleadstothesubstitutionofaglutamicacidforvalineat

position6ofthebetachain,resultingintheproductionofHb

Swhoseexpressioncausessicklingofredbloodcells,

poly-merizingHbwithresultingvaso-occlusion,painandchronic

organdamage.1–3(D)HbSisthemostcommonabnormalHb

inBrazil.2(D)

Sicklecellanemiaoccurswhenthepatientishomozygous

for the Hb S gene (Hb SS). Moreover, Hb S can be

associ-atedwithotherabnormalHb,suchasHbS/beta-thalassemia,

Hb SC, Hb SD, persistence of Hb fetal (Hb F) with Hb S,

amongothers. Theterm SCD defines both sickle cell

ane-miaand these associations. Thecombination ofthe Hb S

genewithnormalHb(HbA)characterizesthesicklecelltrait

(HbAS).1–3(D)

ThediagnosisofSCD,aconditionwithhighmorbidityand

mortality rates, is made atbirth with neonatal screening.

Thepathophysiologyiscomplexandevolveswithacuteand

chroniccomplicationsthat affect differentorgans and

sys-tems.

BecauseofthecomplexityofSCD,manyquestionswere

askedduringthedevelopmentoftheseguidelinesandsoit

was decidedtopresent them in threeparts. Thefirst part

discusses diagnosis by neonatal screening and aspects of

vaso-occlusivecrisis,thesecondpartanswersquestionsabout

splenicsequestrationand thecentralnervous systemfrom

diagnosis to treatment and the third part deals with the

preventionofinfections,diagnosisandtreatmentoffever,

pri-apismandbonemarrowtransplantation.

Objective

Theaimofthefirstpartoftheseguidelinesistheapproachto

diagnosisbyneonatalscreeningandsubsequentconfirmation

ofSCDandquestionsrelatedtothediagnosisandtreatment

ofthevaso-occlusivecrisis.

What

is

the

prevalence

of

sickle

cell

disease

and

how

are

the

results

of

neonatal

screening

for

hemoglobinopathies

interpreted?

P:Allnewbornbabies

I:Resultsofneonatalscreening

C:

O:Interpretationoftheresults

The laboratory techniques used to identify hemoglobin

in the Newborn Screening Program are high-performance

liquid chromatography(HPLC)and isoelectricfocusing(IEF)

because thesetestscanquantifysmallamountsofHb;the

main Hb in the newbornis Hb F.4–16 (A),17 (B) Several

dis-eases areinvestigatedduringneonatalscreening, including

SCD,phenylketonuriaandcongenitalhypothyroidism.4–8,12–16

(A) The Hb with the highest concentration is shown

first in the neonatal screening results and so Hb F will

alwaysbefollowedbytheotherhemoglobins.4–6,14(A)1–3(D)

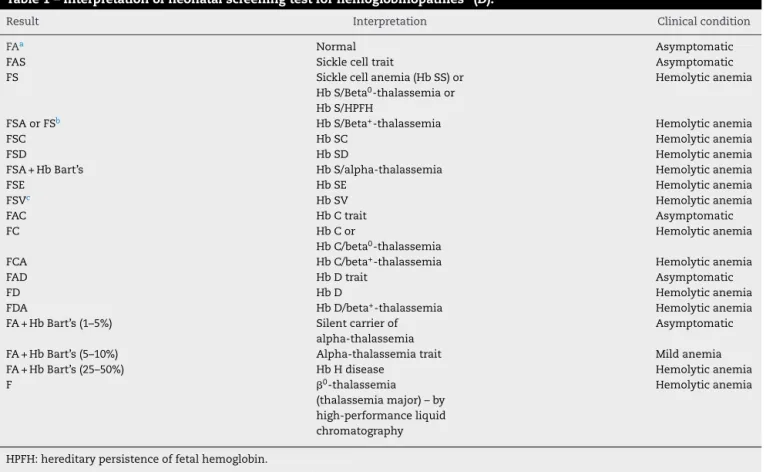

Table 1showshow tointerpret neonatalscreeningresults.

The most common hemoglobinopathies in Brazil are Hb

FAS, Hb FS, Hb FSA, Hb FSC, Hb FSD and Hb FSA+Hb

Bart’s.

TheprevalenceofHbSinBrazilisfrom1.2to10.9%

depend-ingontheregionofthecountry,5,6,13–16(A),17–19(B)whilethe

prevalence of Hb FS (sickle cell anemia) ranges from <0.1

to 0.2%6,7,13–16 (A)17,19 (B) and Hb FSC ranges from <0.1 to

0.9%.5–7,14,15(A)17,18(B)Itisnoteworthythatthestateswiththe

highestnumberofcasesofSCDareBahiaandRiodeJaneiro,

whileParanáand RioGrandedoSulhavethelowest rates.

TheprevalenceofHbCisfrom 0.15to7.4%.5–7,14,15 (A)17–19

(B). HbS/beta-thalassemiahasbeenidentifiedinthestates

ofSãoPaulo,MinasGerais,ParanáandRioGrandedoSul,all

withprevalences<0.1%.5,6,14,16(A)InthecityofRibeirãoPreto,

SãoPaulotheincidenceforsicklecellanemiawasshownto

be1:7,358andforHbSCdisease1:9,365.7(A)InRioGrande

doSulthe incidenceofSCD (HbSS, Hb SC,HbSD and Hb

S/beta-thalassemia)was1:9,1206(A)andinMinasGeraisthe

incidences of Hb FS and Hb FSC were 1:2,800and 1:3,450,

respectively.14(A)

InFrance,SCDprevalencetendstobehigherinthe

pop-ulationofinfantsborntoparentsfromSub-SaharanAfrica,

the Mediterranean, the Arabian Peninsula, French islands

and Indiacompared tothegeneralpopulation(3:10,000 vs.

1:10,000).20 (B) InBrazil,theUSA and theUnitedKingdom,

Table1–Interpretationofneonatalscreeningtestforhemoglobinopathies3(D).

Result Interpretation Clinicalcondition

FAa Normal Asymptomatic

FAS Sicklecelltrait Asymptomatic

FS Sicklecellanemia(HbSS)or

HbS/Beta0-thalassemiaor HbS/HPFH

Hemolyticanemia

FSAorFSb HbS/Beta+-thalassemia Hemolyticanemia

FSC HbSC Hemolyticanemia

FSD HbSD Hemolyticanemia

FSA+HbBart’s HbS/alpha-thalassemia Hemolyticanemia

FSE HbSE Hemolyticanemia

FSVc HbSV Hemolyticanemia

FAC HbCtrait Asymptomatic

FC HbCor

HbC/beta0-thalassemia

Hemolyticanemia

FCA HbC/beta+-thalassemia Hemolyticanemia

FAD HbDtrait Asymptomatic

FD HbD Hemolyticanemia

FDA HbD/beta+-thalassemia Hemolyticanemia

FA+HbBart’s(1–5%) Silentcarrierof

alpha-thalassemia

Asymptomatic

FA+HbBart’s(5–10%) Alpha-thalassemiatrait Mildanemia

FA+HbBart’s(25–50%) HbHdisease Hemolyticanemia

F 0-thalassemia

(thalassemiamajor)–by high-performanceliquid chromatography

Hemolyticanemia

HPFH:hereditarypersistenceoffetalhemoglobin.

a FAbecausefetalHbispredominantatbirth;theresultofthalassemiaminorisalsoHbFA.

b HbFSAisHbSassociatedwithbeta-thalassemia.However,ifthepercentageofHbAisverylow,thephenotypeinneonatalscreeningmay

beHbFS.

c FSVindicatesHbvariantsdifferentfromHbA,HbS,HbC,HbE,HbDandHbBart’s.ThefollowingHbvariantshavebeenidentifiedinBrazil:

HbWoodville,HbChad,HbG-Phil,HbE-Saskatoon,HbRichmond,HbO-Arab,HbBeckman,HbHope.

characteristics.4,10 (A),2 (D) Screening is also universal in

Belgium.11(A)

After the diagnosis of SCD, children and their families

shouldbeprovidedspecialcare,asthereisapossibility of

othercasesofSCDinthefamily.4,8,11,13,15(A),21,22(C)

The interpretation of newborn screening for sickle cell

anemia depends on the initial tests and the confirmation

method used. The proper interpretation and use of these

resultsdependsontheimplementationexperienceof

neona-talscreeningprograms.8(A)

TheNeonatalScreeningProgramforhemoglobinopathies

inBrazilhashadagreatimpactonSCDmortalityand

mor-bidityrates,asearlydiagnosispermitstheuseofprophylactic

antibiotictherapy,specialvaccinationsandthetrainingof

par-entsandcaregiversabouttheclinicalcharacteristicsofSCD,

suchasspleenpalpationforsplenicenlargement.23(D)

Recommendation: The results of neonatal screening

forhemoglobinopathiesshouldbeinterpretedbasedon tests made using HPLC or IEF. As Hb is expressed in decreasingorderofconcentration,HbFwillalwaysbethe firsttobereportedintheresults,followedbyatleastone otherHb.

Is

there

evidence

for

the

need

to

perform

a

confirmatory

electrophoresis

exam

after

the

sixth

month

of

life?

P: Over 6-month-old patients and abnormal hemoglobin resultsinneonatalscreening

I:Bloodcollectionforhemoglobinelectrophoresis C:Resultsofneonatalscreening

O:Interpretationoftheresults

The diagnosis of hemoglobinopathies needs to be con-firmedwhenthechildisaboutsixmonthsoldand,insome situations,astudyoftheparentsormolecularanalysis(DNA) ofthechildshouldbemade.1,2(D),4,6–8,10,11,14–16(A)

Positiveresultsshouldalwaysbeconfirmed.4,5,10–12,24 (A)

Thecombinationofmethods(IEFandHPLC)reducesthe

pos-sibilityoffalsenegativeresultsforSCD,whichcanoccurin

casesofred blood celltransfusions priortosample

collec-tionorprematurity.4,9(A)Falsepositiveresultsforsicklecell

anemiacanbefoundintherarecombinationofHbSandHb

HopedetectedbyIEF.InFrance,twocasesin42infantswith

suspectedHbSS,actuallyhadHbS/HbHope.25(B)

A Brazilian study of 4,635 children from Minas Gerais

screening showed 0.6% of discordant results between the

initialscreeningand anIEFexam after sixmonths oflife.

Sevencaseshadhadbloodtransfusionsbeforeblood

collec-tion,sevencaseshadproblemsinbloodcollectionorinthe

transcriptionoftheexamresults,therewasdifficultyto

dif-ferentiatebetweenHbSandHbDineightcasesandthereason

wasnotidentifiedinfivecases.14(A)

Recommendations: All children identified as having

hemoglobinopathiesduringneonatalscreeningshould be retested by hemoglobin electrophoresis after six monthsoflife.

Is

there

evidence

on

the

factors

that

cause

a

vaso-occlusive

crisis?

P:Patientsbetween0and18yearsoldwithsicklecellanemia andpainfulcrisis

I:Fever,dehydration,infection,metabolicdisorder,exposure toextremecoldandheat,alcoholism,osteomyelitis,illegal drugs(marijuana,cocaine)

C:Withoutsymptoms

O:Triggersofvaso-occlusivecrisis

Several factors have been associated with the vaso-occlusive crisis in patients with SCD, such as infections, climatechange,psychologicalfactors,altitude,acidosis,sleep apnea,stress,dehydration,hypoxiaandphysicalexhaustion. However,inmostcasesthetriggeringfactorisnotidentified.26 (D)

Pain crises in these patients have variable intensities

and frequencies, being higher in winter. Higher

tempera-turesduringwinterwereassociatedwithlesspainintensity

andfrequency.27(B)However,anotherstudydidnotconfirm

the association between changes in temperature and pain

frequency.28(B)Moreover,thehospitalizationrateforpain

cri-sisincreaseswiththeintensityofwindandairhumidity.29,30

(B)

Somefactorsincreasethelikelihoodofhospitalizationfor

painfulcrisisinpatientswithSCD.Inamultivariateanalysis

offactorsassociatedwithcrisis,increasedriskof

hospitaliza-tionwasobservedinsubjectswithHbSS(hazardratio:3.1),in

thoseexposedtosmoking(hazardratio:1.9)andthosewith

ahistory ofasthma (hazard ratio:1.3).31 (B)Another study

demonstratedtheimportanceofrespiratorysymptomsand

asthmainpain crisis.32 (B)Anassessmentofnocturnal O

2

saturationandpainfulcrisisin90patientswithsicklecell

ane-miaconcludedthatanocturnalO2saturation<90%(p-value

<0.0001),Hbbelow8.8g/dL(p-value<0.01)andahematocrit

below28%(p-value<0.0012)areassociatedwiththeonsetof

symptoms.33(B)

Otherclinicalsituationsareassociatedwithpaincrisisin

patientswithSCD, including high bloodviscosity34 (B)and

menstruation(61.5%ofcasesofcrisisinwomenoccurduring

menstruation).35(C)

Recommendation: Factors associated with pain

cri-sis can be environmental, suchas temperature, wind and humidity or clinical such asrespiratory diseases, increased blood viscosity, anemia and menstruation. Smokingincreasestheriskofhospitalizationandsome infections increase the risk of having apainful vaso-occlusivecrisis.

Is

there

evidence

that

the

use

of

pain

assessment

scales

is

a

good

method

to

monitor

pain

related

to

vaso-occlusive

crisis?

P:Patientsbetween0and18yearsoldwithsicklecellanemia andpainfulcrisis

I:Followinguptreatmentusingpre-establishedpainscales C: Following up treatment without using pre-established painscales

O:Adequatepaincontrol

Thereareseveralchallengestopainmanagementinsickle cell anemia, such as disregarding the level of pain felt by patients,thedifficultyto‘quantify’thispain,thebest instru-menttoassesspain,thediscrepancybetweenpainandpatient behavior,theinadequateprescriptionofanalgesiaandthefear thatthepatientbecomesdependentonopioids.Onlyby eval-uatingthetrueintensityofthepain,isitpossibletoofferthe besttreatment.36(B)

Three methodsare used toevaluatepainintensity. The

African-American Oucher scale is designed for children

between 3 and 12 years and gives scores of0–100 for the

intensityofpain;itconsistsofaseriesofpicturesofchildren

expressing different levels ofpain. TheWong-Baker FACES

scaleusespainscoresbetween0and5,andcanbeusedin

over3-year-oldchildren;itiscomprisedofaseriesofdrawings

offacesexpressingdifferentlevelsofpain.Thevisualanalog

scale(VAS)usesahorizontal10-cmlineonpaper,whereone

endisdesignatedasnopainandtheotherisdesignatedas

extremepain;thepatientindicatesatwhatlevelhis/herpain

isonascaleof0–10.37(B)

Acriticalissueinthemanagementofpaininsicklecell

anemia is precisely which scale is most appropriate. An

assessmentofthepainof100childrenwithsicklecellanemia

and vaso-occlusivecrisisusingthethreemethods

(African-AmericanOucherscale,VASandtheWong-BakerFACESscale)

showedthattheFACESandOucherscaleswereequallyvalid

andreliableasinstrumentstoevaluatepain,but56%of

chil-drenand adolescentspreferredthe FACESscale.Thevisual

analogscalehadthelowestdegreeofreliability.37(B)

Aretrospectivestudyof3-to21-year-oldpatientsusedthe

VAS tocompare152episodesofpainduetovaso-occlusion

in77 patientswithSCDversus221episodesofpainin219

patientswithlong bonefracture. Thepain scoreswere

sig-nificantlyhigherinthechildrenwithpainfulvaso-occlusive

crisis(7.7±2.5vs.6.7±3.0;p-value=0.005).InSCDpatients,

therewasnorelationshipbetweenanypainassessmentscale

A retrospective study of 279 episodes of painful

vaso-occlusivecrisis(initiallytreatedwithonedoseofmorphine)

in105over 8-year-old childrenwithSCD foundthat

appli-cationofthe Wong-BakerFACES painscale (0–5)canguide

analgesiamanagement.Theinitialscorewashigherin

hos-pitalizedcomparedtonon-hospitalizedchildren(4.4vs.3.9;

p-value=0.002). The FACES scale allowed a more accurate

assessmentofthenecessityofhospitalizationinover

8-year-oldSCDchildrenwithpainfulcrisiswhowerebeingtreated

withmorphine.39(B)

Aprospectivestudyof232over16-year-oldSCDpatients

whoself-reportedpaineverydayduringsixmonthsusinga

painscalebetween0and9,reportedthatthemeanpain

inten-sityincreasedasthepercentageofdayswithpainincreased

(p-value<0.001).Painwasreportedon56%ofthetotal

patient-days; pain crises without attending amedical service was

reportedon13%ofthedaysandmedicalcarewasusedonly

in3.5%ofthedays.About30%ofpatientsreportedpainon

morethan95%ofthedays.Basedinthescale,theuseof

opi-oidswashigherondayswithmorepain(p-value<0.001).Thus,

thepainscalealsoallowscontrolofpainoutofthehospital

withouttheindiscriminateuseofopioids.40(B)

Themedicationquantificationscale(MQS)associatedwith

apainscaleappliedin27SCDchildrenhospitalizedforpainful

crisis,allowsmonitoringregardingtheuseofanalgesicsand

painintensity.Inthisprospectivestudy,59.3%describedthe

onsetofpainassuddenandthatpaincontinuedtobeconstant

for70.4%ofpatientsfromthetimeofonsetuntiladmission

tothehospital.UsingtheAfrican-AmericanOucherscale,the

meanscoreofpainintensityonthedayofhospitalizationwas

84±9.9(range:63.8–100),andtheinitialmeanscoreoftheMQS

was15.7±4.9(range:6–24).Afterdrugtherapy(morphinewas

themostfrequent),thisscoredropped1.2±0.5pointsforeach

dayofhospitalization(range:0.9–2.5;p-value<0.0001).There

wasacorrelationbetweenthepainlevelanddrugdose;the

MQSprovedtobeasensitiveandusefultooltoquantifythe

utilizationofanalgesicsinSCD.41(B)

ThepainlevelmeasuredusingtheVAS(scoresof0–100)

in74SCDadultswithvaso-occlusivecrisisidentifiedamean

scoreof80[95%confidenceinterval(CI):75.99–82.95]onarrival

athospital.Thereductioninpainfollowingtheuseof

anal-gesics was monitoredusing the VAS. Inpatients reporting

a significant improvementin pain, the change in the VAS

was23.4(95%CI:15.4–31.4),whileitwasonly13.5(95%CI:

11.25–15.74)inthoseinwhomtheimprovementwasminimal.

Thestudyconcludedthattheminimumclinicallysignificant

scoretoassessimprovementinpainduringtreatmentwith

analgesiawas13.5;thisalsoallowsanevaluationofpainrelief

inadultswithSCD.42(B)

Apainintensityscale(numericratingscale)wasusedto

predicthospitalizationof65patientsagedbetween13and53

yearsold(mean:23years)withSCDandvaso-occlusivecrisis

and80acuteeventsthatresultedin49hospitalizations.The

meaninitialscoreforpain was8.5inhospitalizedpatients

and5.1forthosewhoweredischarged(p-value<0.001).When

consideringascoreof6.5asthecutoffpoint,thesensitivity

was0.886andspecificitywas0.762,withpositiveandnegative

predictivevaluesof0.886and0.760,respectively.Therefore,

the pain score allows an indication for hospitalization.43

(B)

In theassessmentofpain in17SCD childrenusing the

FACESscale,thelevelofpainpredictedthelengthof

hospi-talization.Childrenwithahighscore(>2)24hafterreceiving

medicationsspentmoretimeinhospital.44(B)

Recommendation:TheuseofpainscalesinSCDpatients withvaso-occlusivecrisiscanguidetreatment,monitor responseandpredicthospitalization.

What

is

the

best

sequence

of

medications

to

control

painful

vaso-occlusive

crisis?

P:Patientsbetween0and18yearsoldwithsicklecellanemia andpainfulcrisis

I:Treatmentwithmorphineversusmeperidine C:Treatmentwithparacetamolordipyrone O:Adequatepaincontrol

The treatment of painful vaso-occlusive crisis in SCD patients involves correcting triggering factors, such as hypoxia,infection,acidosis,dehydration,physicalexhaustion andexposuretoextremecold.Themanagementofpainful cri-sisisbasedonnon-randomizedclinicalstudies45,46(A),47(B),

andmainlyconsistsofhydrationandanalgesia.48 (A)Thus,

manyguidelineshavebeenwrittentoprovidesupportinthe

treatmentofpaininsicklecellanemia.49,50(D)

Theproperuseofanalgesicsisimportantandthe

prescrip-tion should suitthe intensityofpain, witha fixeddoseat

specificintervals,andnotusingmedications‘asnecessary.’

Theuseofmedicationsforpainmanagementinover

12-year-old childrenand adults should follow the threesteps

oftheanalgesiascale (Table2)recommendedbytheWorld

HealthOrganization(WHO)51,52(D).

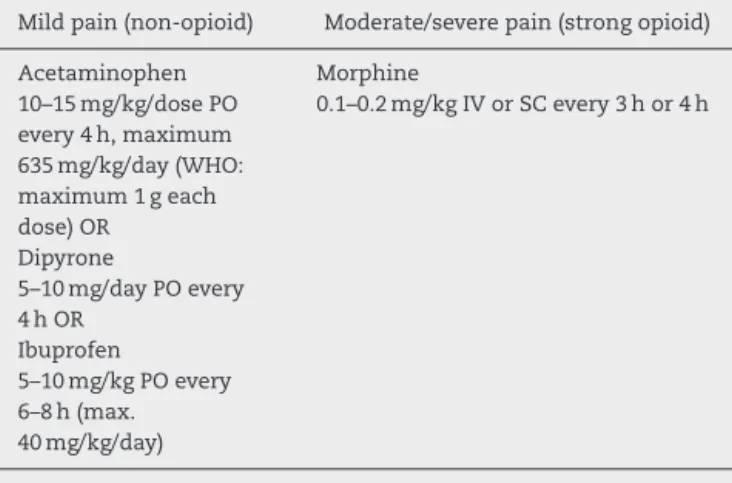

For under 12-year-oldchildren,the use ofdrugs forthe

managementofpainisalittledifferentbecausetheanalgesia

scale,asrecommendedbyWHOguidelinespublishedin2012,

hasonlytwosteps(Table3)53(D).

Thetwo-stepapproachconsiderstheuseoflowdosesof

strongopioidanalgesicsforthetreatmentofmoderatepain

becauseitisnotsafetousecodeineinchildrendueto

prob-lems relatedtogeneticvariabilityinbiotransformation and

insufficientdatafromclinicalstudiesinchildrenusingother

intermediateopioidssuchastramadol.53(D)

Treatment ofmildto moderatepain inover 12-year-old

childrenand adultsshould startwithanon-opioiddrugat

therecommendeddoseandfrequencytogetherwithadjuvant

medicationsasnecessary.Ifthepaindoesnotstop,addaweak

opioid.Iftheweakopioidcombinedwithanon-opioiddrug

doesnotcontrolthepain,theweakopioidshouldbereplaced

byastrongopioid.48(A)49,52(D)

Inunder 12-year-oldchildrenwithmildpain, treatment

shouldstartwithanon-opioiddrugattherecommendeddose

andfrequency;ifpaindoesnotimprove,alowdoseofastrong

opioidshouldbeaddedwiththe dosebeingincreasedonly

ifthepaindoesnotimprove.Afterastartingdoseaccording

Table2–StepsofpainmanagementlistedintheanalgesiascaleasrecommendedbytheWorldHealthOrganization– over12-year-oldchildrenandadults51,52(D).

Mildpain Visualpainscale(1–4)

Moderatepain Visualpainscale(5–7)

Severepain Visualpainscale(8–10)

Non-opioid Weakopioid Strongopioid

Aspirin

30–60mg/kg/dayPOevery4h maximum3.6g/24h OR

Acetaminophen

10–15mg/kg/dosePOevery4h maximum635mg/kg/day OR

Dipyrone

5–10mg/dayPOevery4h

Codeine

0.5–0.75mg/kg/dosePOevery4h

Codeine

0.75–1mg/kg/doseIVorPOevery 4h

OR Morphine

0.1–0.2mg/kgIVorSCevery3hor 4h

OR Tramadol 0.1–0.25mg/kg/hIV

Ibuprofen

5–10mg/kgPOevery6hto8h

Tramadol 0.5mg/kgIV

maximum5mg/kg/dayevery6h

PO:peros;IV:intravenous;SC:subcutaneous.

Table3–Stepsofpainmanagementlistedinthe analgesiascalerecommendedbytheWorldHealth Organization–under12-year-oldchildren53(D).

Mildpain(non-opioid) Moderate/severepain(strongopioid)

Acetaminophen 10–15mg/kg/dosePO every4h,maximum 635mg/kg/day(WHO: maximum1geach dose)OR

Dipyrone

5–10mg/dayPOevery 4hOR

Ibuprofen

5–10mg/kgPOevery 6–8h(max. 40mg/kg/day)

Morphine

0.1–0.2mg/kgIVorSCevery3hor4h

PO:peros;IV:intravenous;SC:subcutaneous.

beadjustedtothelevelthatiseffective(withnomaximum dose).Themaximumincreaseindosageis50%every24hin outpatientsettings.53(D)

Do not use meperidine because, besides having one

tenth ofthe analgesic power ofmorphine, it is associated

withserious adverseevents,suchas seizuresand physical

dependence.49,50,54,55(D)

Intravenous morphine is considered the treatment of

choicefor the severe pain crisis insickle cell anemia, but

itisassociatedwithseveraladverse eventsincludingacute

chest syndrome. Patient-controlled administration of

mor-phinecomparedtocontinuoususewasnomoreeffectivein

respecttopainmanagementandlengthofhospitalstay,butit

significantlyreducedopioidconsumptionandproducedfewer

adverseevents.56(B)

A randomized, double blind, parallel-group study

com-pared the use oforal versus continuous intravenous

mor-phine.Initialpainmanagementusedintravenousmorphine

(upto0.15mg/kg).Subsequently,acomparisonbetweenoral

morphine(1.9mg/kgevery12h)andcontinuousintravenous

morphine (0.04mg/kg/h)wasmade forthe managementof

painepisodesinsicklecellanemiapatients;therewasno

dif-ference inthe resolutionofpain northe timeofanalgesic

administration.Theneedforrescueanalgesiawassimilar,as

weretheadverseeffects.Oralmorphinemaybeanalternative

totheuseofcontinuousintravenousmorphine.57(B)

Theuseoforalorintravenousmethylprednisoneatadose

of15mg/kgintwodosesinthefirst24hcombinedwith

mor-phine can produce benefits to reduce the time needed to

resolvepaininepisodesofseverepain.However,theuseof

corticosteroidsisassociatedwithareboundeffectwiththe

worsening ofpainwhenits administrationisstopped, and

itsindicationmustbecarefullyconsidered.58 (B)Theuseof

corticosteroidsfavorspainfulcrisiswhenusedinacutechest

syndrome.59(D)

Theuseofnitricoxideinthetreatmentofpainful

vaso-occlusivecrisisofhospitalizedsicklecellanemiapatientsdoes

notshortenthetimerequiredforcrisisresolution,doesnot

reducethelengthofhospitalization,doesnotaffectthe

inten-sity ofpain or chestpain, and does notreduce the useof

opioids.60(A)

Recommendation: Painmanagement ofvaso-occlusive

Is

there

evidence

for

the

use

of

adjuvant

medications

such

as

non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory

drugs,

antihistamines,

antidepressants,

benzodiazepines,

anticonvulsants

or

corticosteroids

in

the

management

of

painful

vaso-occlusive

crisis?

P:Patientsbetween0and18yearsoldwithsicklecellanemia

andpainfulcrisis

I: Treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

(diclofenac, nimesulide, aspirin, COX 1 inhibitors and

COX2inhibitors),antihistamines,antidepressants,

benzo-diazepinesandanticonvulsants

C:Treatmentwithparacetamolordipyrone

O:Adequatepaincontrol

Therearefewrandomizedclinicaltrialsonthetreatment

ofthepainfulcrisisinsicklecellanemia45(A),46(B),sothat

mostofthetreatmentisbasedondatafromnon-randomized

studies.49,55,61,62(D)

Five studieswith non-steroidalanti-inflammatorydrugs

(NSAIDs)asadjuvantpainmedicationsforchildrenandadults

withSCDwerereviewed.Oraldiflunisalwassimilartoplacebo.

Twostudieswithintravenousketorolacinhospitalizedadults

werefavorabletoketorolacforpaincontrol,whiletwo

oth-erswerenot.Thesmallsamplesizesandtheheterogeneityof

themethodsprecludeanyconclusionintheuseofNSAIDto

treatpaininSCDandmakeanymeta-analysisonthissubject

unrealistic.45 (A)AphaseIIItrial,doubleblind,randomized,

placebo-controlledof66episodesofpainfulvaso-occlusive

cri-sisconcludedthatketorolacwasnoteffectivetocontrolthe

painandtheuseofmorphinewhencomparedtoaplacebo.

Theauthorsdonotrecommendthesystematicuseof

ketoro-lac in these patients.63 (A) No studies were found in the

literatureonotherNSAIDs,suchasacetaminophen.45(A)

A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study in

Brazilshowednobenefitwiththeuse ofpiracetamin

chil-drenand youngadultswithsickle cellanemia andpainful

vaso-occlusive crisisinrelation tothe use ofopioids,pain

intensityandhospitalization.64(A)Piracetamisineffectivein

thepreventionofvaso-occlusivepaincrisis.64(A)Thesedata

wereconfirmedinameta-analysiswiththreestudies,

includ-ingtheBrazilianstudy,whereitwasconcludedthatthereare

insufficientdatatoindicatepiracetamforpainfulcrisisinSCD

patients.65(A)

Methylprednisoloneorintravenous dexamethasone

sug-gestbenefitsinrelationtopainmanagement,butpatientswho

receivedasingledoseofcorticosteroidshadahigherriskof

painreactivation.45(A)

Magnesiumisavasodilatorthatenhancesthehydrationof

redbloodcells.Forthisreasonitwasinvestigatedina

random-ized,double-blind,placebo-controlledstudy of104children

withSCD hospitalized to receive intravenous analgesia for

painfulcrisis.Intravenousmagnesiumsulfatehadnoeffect

onreducingthelengthofhospitalstay,improvementsinpain

orreductionsinthecumulativedoseofanalgesics.66(A)

Adjuvantmedicationshavebeenusedtoenhancethe

anal-gesiceffectofopioidsinpatientswithcancerandtodecrease

their adverse events. Antihistamines (chlorpheniramine

0.15mg/kg/day orally every 6h with a maximum dose of

12mg/day),antidepressants(amitriptyline10–20mgorallyat

night), benzodiazepines(thedose dependsonthe

benzodi-azepine)andanticonvulsants(carbamazepine5–10mg/kg/day

onceortwiceaday)havemildanalgesiceffects.When

indi-cated,thesemedicationsshouldbeusedcarefully.49,51,52(D)

Recommendations:Thereisnoconsistentevidence

sup-portingtheuseofantidepressants,benzodiazepinesand anticonvulsants in the management of painful vaso-occlusive crisis in sickle cell anemia. There are no benefits with piracetam or magnesium sulfate use in painfulvaso-occlusivecrisis.

Is

there

evidence

for

the

use

of

oxygen

therapy

or

hyperhydration

in

the

management

of

painful

vaso-occlusive

crisis?

P:Patientsbetween0and18yearsoldwithsicklecellanemia andpainfulcrisis

I:Treatmentwithoxygentherapyorhyperhydration C:Treatmentwithoutoxygentherapyorhyperhydration O:Adequatepaincontrol

Althoughinhaledoxygentherapy(50%oxygen)inpatients withSCDreversesthesicklingofredbloodcells,thereisno evidenceintheliteraturethatitsuseinvaso-occlusivepain crisisprovidesbenefitsbyreducingthepain,theuseofopioids orhospitalization.67,68(B)

Dehydrationisanimportantfactorinthesicklingprocess.

Thedecreased abilitytoconcentrateurine, acharacteristic

ofSCDpatients, resultsininadequatecontrolofhydration.

Thus, duringpainful crisis, patientsreceive intravenous or

oralhydration,regardlessoftheirstateofhydration.However,

careisnecessarynottocausecardiacorpulmonaryvolume

overload.Norandomizedcontrolledtrialsreportbenefitsin

respecttoimprovingorresolvingpainwiththe infusionof

intravenousfluidsasadjuvanttreatmentinsicklecellanemia

patientswithpainfulvaso-occlusivecrisis,regardlessofthe

stateofhydration.47(A)

Hydrationinpatientswithsicklecellanemiashouldbe

car-ried out withcaution.Hypotonic solutionsmay beusedto

establishbaselinehydration,maximum1–1.5timesthe

main-tenancevolumeincludingthemedicationsvolume.49,55,61,69,70

(D)Careshouldbetakentoavoidexcessivehydrationbecause

it decreasesthe plasmaoncoticpressureand increasesthe

hydrostatic pressure,withrisk ofpulmonaryedema

(espe-cially in patients with kidney disease, heart disease or

previouslungdisease).70(D)

Recommendations: Thereisno publishedevidenceon

Is

there

evidence

that

bone

scintigraphy

is

a

good

test

to

differentiate

the

painful

vaso-occlusive

crisis

from

osteomyelitis?

Is

there

any

test

that

allows

this

differentiation?

P:Patientsbetween0and18yearsoldwithsicklecellanemia

anddoubtsbetweenpainfulcrisisandosteomyelitis

I:Bonescintigraphy

C:Clinicaldiagnosis

O:Differentialdiagnosisbetweenpainfulvaso-occlusive

cri-sisandosteomyelitis

Insicklecellanemia,boneinfarctionisabout50timesmore

commonthan osteomyelitis.71 (B)However,the

differentia-tionbetweenosteomyelitisandboneinfarctionisdifficult.In

bothsituationsthepatientcanhavepain,fever,edema,

ery-thema,andleukocytosisandimagingtests(X-ray,computed

tomography)arenonspecific.72,73(B)

Aprospectivestudyof42episodesofbonepaininchildren

withSCDshowedthatinmostcasesthe diagnosisofbone

infarctionisclinical.However,scintigraphywithtechnetium

canhelpincaseswherethereisdoubtaboutosteomyelitis.

When bonemarrowscintigraphy withtechnetiumismade

withintendaysofonset,theuptakeisnormalattheinjury

site in the case of osteomyelitis (100% of cases) while in

boneinfarctiontheuptakeisdiminished(93%ofcases).Bone

scintigraphywithtechnetiumhasproveneffectivetoidentify

osteomyelitisin100%ofcasesduetothehigheruptake,butit

isnotspecificforboneinfarction.74(B)

Combinationofsequentialboneandbonemarrow

scintig-raphy withtechnetium showed benefitsin the differential

diagnosisofboneinfarctionandosteomyelitisin39children

withSCDandbonepain.Theseexamsshouldbeperformed

within 72h of the onset ofpain. Decreased bone marrow

uptakeassociated withnormal or reduced boneuptake in

scintigraphysuggestsadiagnosisofboneinfarction,whereas

increasedboneuptakesuggestsinfection.75(B)

Scintigraphyimagesof79 childrenwith SCDperformed

within24hoftheonsetofpainwereretrospectivelyanalysed.

Bonemarrowscintigraphywithtechnetiumwasperformed

followedbybonescintigraphy.Reduceduptakebythebone

marrowand abnormalboneuptakesuggestedbone

infarc-tionandnormaluptakebythebonemarrowwithincreased

boneuptakesuggestedosteomyelitis.Seventycasesofbone

infarctionwerediagnosedwith66beingsuccessfullytreated

withoutantibiotics.Fourcaseswerediagnosedas

osteomyeli-tis,inwhichthreecultureswerepositive;nofalsenegative

resultswereobserved.73(B)

A retrospective study of 22 episodes of suspected

osteomyelitisinSCDchildrenshowedthatthecombination

ofbonescintigraphywithgalliumandtechnetiumcanhelpin

thedifferentialdiagnosisofboneinfarctionand

osteomyeli-tis.Thebestdatafordiagnosisareobtainedwithin24hafter

theonsetofsymptoms.72(B)Theuseofbonemarrow

scintig-raphywithgalliumandtechnetiumwasalsoeffectiveforthis

differentialdiagnosisinastudyof18episodesofpain.76(C)

Aprospectivestudyof53SCDchildrenwiththeneedto

differentiatebetween vaso-occlusive crisis and

osteomyeli-tisfoundultrasoundchangesofthesofttissuesuggestiveof

osteomyelitisin17patients;puswasdrainedfromallpatients.

Theauthorssuggestthatultrasoundshouldbeconsideredas

the first optiontoinvestigateosteomyelitis.77 (B) The

over-all sensitivityof soft tissueultrasound in the diagnosis of

osteomyelitiswas74%withaspecificityof63%.78(C)The

ultra-soundwasnormalincasesofboneinfarction,andperiosteal

elevation,subperiostealorintramedullaryabscessesand

cor-ticalboneerosioncanbeobservedinosteomyelitis.77(B)78(C)

Thediagnosisofosteomyelitisbyultrasoundcanbeenhanced

byinvestigatingreactive proteinCserum levelsand

leuko-cyte counts, as these values are significantly increased in

osteomyelitis.79(B)

Magneticresonanceimaging(MRI)isagoodimagingexam

toevaluatethebonemarrowandtodetect boneinfarction.

However,inSCD,itisdifficulttodifferentiatebetween

infarc-tionandosteomyelitiswithMRI.80(D)

Althoughimagingtestscanhelptodifferentiatebetween

bone infarction and osteomyelitis, a clinical diagnosis is

alwaysbetter.73,74,81(B)

Recommendation: Differentiating bone infarction and

osteomyelitis remainsachallengebecausethe clinical presentationissimilarinbothcasesandlaboratorytests are still of limited use. Bone scintigraphy with tech-netiumdoesnothelptodifferentiateboneinfarctionin sickle cell anemia patients withbone pain. Thus, the combinationofboneandbonemarrowscintigraphywith technetium can assist in the differentiation between osteomyelitis and boneinfarction,ascanscintigraphy usinggalliumandultrasoundofthesofttissues.MRImay playaroleandbesoughtwhereverpossibleincasesof feverandprolongedpain.

Conflicts

if

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Appendix

A.

PICO1

What is the prevalence of sickle cell disease and how

aretheresultsofneonatalscreeningforhemoglobinopathies interpreted?

((Anemia, Hemolytic, Congenital AND screening AND neonatal)) OR (((screening AND neonatal)) AND (Hemoglobinopathies))

PICO2

Isthereevidencefortheneedtoperformaconfirmatory electrophoresisexamafterthesixthmonthoflife?

(Anemia, Sickle Cell OR Hemoglobinopathies OR Hemoglobins) AND (Electrophoresis) AND (Neonatal OR Newborn)

PICO3

SicklecellanemiaAND(veno-occlusivediseaseOR

veno-occlusivesyndromeORpainORvaso-occlusiveORvascular

disease ORcrisis) AND (fever ORdehydration OR infection

OR metabolic syndrome OR cold OR heat OR alcohol OR

osteomyelitisORcocaineORmarihuanaORetiologyORrisk)

PICO4

Isthereevidencethattheuseofpainassessmentscales isagoodmethodtomonitorpain relatedtovaso-occlusive crisis?

SicklecellanemiaAND(veno-occlusivediseaseOR

veno-occlusivesyndromeORpainORvaso-occlusiveORvascular

diseaseORcrisis)AND(SeverityofIllnessIndexORscaleOR

scoreORVASORmeasurement)

PICO5

Whatisthebestsequenceofmedicationstocontrolpainful vaso-occlusivecrisis?

(Therapy/broad[filter]ANDSicklecellanemiaAND

(veno-occlusivedisease ORveno-occlusive syndrome ORpain OR

vaso-occlusiveORvasculardiseaseORcrisis))

PICO6

Isthereevidencefortheuseofadjuvantmedicationssuch as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antihistamines, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants or cor-ticosteroids in the management of painful vaso-occlusive crisis?

(Therapy/broad[filter]ORanti-inflammatoryORHistamine

Antagonists OR anticonvulsant OR Benzodiazepines) AND

Sickle cell anemia AND (veno-occlusive disease OR

veno-occlusivesyndromeORpainORvaso-occlusiveORvascular

diseaseORcrisis)

PICO7

Isthereevidencefortheuseofoxygentherapyor hyperhy-drationinthemanagementofpainfulvaso-occlusivecrisis?

SicklecellanemiaAND(veno-occlusivediseaseOR

veno-occlusivesyndromeORpainORvaso-occlusiveORvascular

diseaseORcrisis)AND(oxygentherapyOROXYGENORFluid

TherapyORInfusions,ParenteralORHYDRATIONOR

DEHY-DRATION)

PICO8

Isthereevidencethatbonescintigraphyisagoodtestto differentiatepainfulvaso-occlusivecrisisfromosteomyelitis? Isthereanytestthatallowsthisdifferentiation?

((RadionuclideImaging))AND(sicklecellanemia)

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1. NationalInstituteofHealth,NationalHeart,Lung,andBlood Institute,DivisionofBloodDiseasesandResources.The managementofsicklecelldisease;2002.

2. AgênciaNacionaldeVigilânciaSanitária(Anvisa).Manualde

DiagnósticoeTratamentodeDoenc¸asFalciformes;2002.p.

142.Availablefrom:http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/

publicacoes/anvisa/diagnostico.pdf[cited10.01.15][Internet]. 3. BragaJA,LoggettoSR,CampanaroCM,LyraIM,VianaMB,

AnjosAC,etal.Doenc¸afalciforme.In:LoggettoSR,BragaJA, ToneLG,editors.HematologiaeHemoterapiaPediátrica.São Paulo:Atheneu;2014.p.139–62.

4. ShaferFE,LoreyF,CunninghamGC,KlumppC,VichinskyE, LubinB.Newbornscreeningforsicklecelldisease:4yearsof

experiencefromCalifornia’snewbornscreeningprogram.J PediatrHematolOncol.1996;18(1):36–41.

5.BrandeliseS,PinheiroV,GabettaCS,HambletonI,SerjeantB, SerjeantG.NewbornscreeningforsicklecelldiseaseinBrazil: theCampinasexperience.ClinLabHaematol.2004;26(1):15–9.

6.WagnerSC,deCastroSM,GonzalezTP,SantinAP,ZaleskiCF, AzevedoLA,etal.Neonatalscreeningfor

hemoglobinopathies:resultsofapublichealthsystemin SouthBrazil.GenetTestMolBiomarkers.2010;14(4):565–9.

7.MagalhãesPK,TurcatoMdeF,AnguloIdeL,MacielLM. Neonatalscreeningprogramattheuniversityhospitalofthe RibeirãoPretoSchoolofMedicine,SãoPauloUniversity, Brazil.CadSaudePublica.2009;25(2):445–54.

8.StreetlyA,LatinovicR,HallK,HenthornJ.Implementationof universalnewbornbloodspotscreeningforsicklecelldisease andotherclinicallysignificanthaemoglobinopathiesin England:screeningresultsfor2005-7.JClinPathol. 2009;62(1):26–30.

9.DucrocqR,PascaudO,BévierA,FinetC,BenkerrouM,ElionJ. Strategylinkingseveralanalyticalmethodsofneonatal screeningforsicklecelldisease.JMedScreen.2001;8(1):8–14.

10.AlmeidaAM,HenthornJS,DaviesSC.Neonatalscreeningfor haemoglobinopathies:theresultsofa10-yearprogrammein anEnglishHealthRegion.BrJHaematol.2001;112(1):32–5.

11.LêPQ,FersterA,CottonF,VertongenF,VermylenC, VanderfaeillieA,etal.SicklecelldiseasefromAfricato Belgium,fromneonatalscreeningtoclinicalmanagement. MedTrop(Mars).2010;70(5–6):467–70.

12.Bardakdjian-MichauJ,BahuauM,HurtrelD,GodartC,RiouJ, MathisM,etal.Neonatalscreeningforsicklecelldiseasein France.JClinPathol.2009;62(1):31–3.

13.DinizD,GuedesC,BarbosaL,TauilPL,MagalhãesI. Prevalenceofsicklecelltraitandsicklecellanemiaamong newbornsintheFederalDistrict,Brazil,2004to2006.Cad SaudePublica.2009;25(1):188–94.

14.PaixãoMC,CunhaFerrazMH,JanuárioJN,VianaMB,LimaJM. ReliabilityofisoelectrofocusingforthedetectionofHbSHb C,andHBDinapioneeringpopulation-basedprogramof newbornscreeninginBrazil.Hemoglobin.2001;25(3):297–303.

15.LoboCL,BuenoLM,MouraP,OgedaLL,CastilhoS,deCarvalho SM.NeonatalscreeningforhemoglobinopathiesinRiode Janeiro,Brazil.RevPanamSaludPublica.2003;13(2–3):154–9.

16.WatanabeAM,PianovskiMA,ZanisNetoJ,LichtvanLC, Chautard-Freire-MaiaEA,DomingosMT,etal.Prevalenceof hemoglobinSintheStateofParana,Brazil,basedonneonatal screening.CadSaudePublica.2008;24(5):993–1000.

17.AdornoEV,CoutoFD,MouraNetoJP,MenezesJF,RêgoM,Reis MG,etal.HemoglobinopathiesinnewbornsfromSalvador, Bahia,NortheastBrazil.CadSaudePublica.2005;21(1):292–8.

18.BandeiraFM,LealMC,SouzaRR,FurtadoVC,GomesYM, MarquesNM.Hemoglobin“S”positivenewborndetectedby cordbloodanditscharacteristics.JPediatr(RioJ).

1999;75(3):167–71.

19.deAraújoMC,SerafimES,deCastroWAJr,deMedeirosTM. PrevalenceofabnormalhemoglobinsinnewbornsinNatal, RioGrandedoNorte,Brazil.CadSaudePublica.

2004;20(1):123–8.

20.ThuretI,SarlesJ,MeronoF,SuzineauE,CollombJ,Lena-Russo D,etal.NeonatalscreeningforsicklecelldiseaseinFrance: evaluationoftheselectiveprocess.JClinPathol.

2010;63(6):548–51.

21.MillerFA,HayeemsRZ,BombardY,LittleJ,CarrollJC,Wilson B,etal.Clinicalobligationsandpublichealthprogrammes: healthcareproviderreasoningaboutmanagingtheincidental resultsofnewbornscreening.JMedEthics.2009;35(10):626–34.

23.BainBJ.Haemoglobinopathydiagnosis:algorithms,lessons andpitfalls.BloodRev.2011;25(5):205–13.

24.BoemerF,VanbellinghenJF,BoursV,SchoosR.Screeningfor sicklecelldiseaseondriedblood:anewapproachevaluated on27,000Belgiannewborns.JMedScreen.2006;13(3):132–6.

25.DucrocqR,BévierA,LeneveuA,Maier-RedelspergerM, Bardakdjian-MichauJ,BadensC,etal.Compound

heterozygosityHbS/HbHope(beta136Gly→Asp):apitfallin thenewbornscreeningforsicklecelldisease.JMedScreen. 1998;5(1):27–30.

26.ShapiroBS.Themanagementofpaininsicklecelldisease. PediatrClinNorthAm.1989;36(4):1029–45.

27.SmithWR,BausermanRL,BallasSK,McCarthyWF,Steinberg MH,SwerdlowPS,etal.Climaticandgeographictemporal patternsofpainintheMulticenterStudyofHydroxyurea. Pain.2009;146(1–2):91–8.

28.SlovisCM,TalleyJD,PittsRB.Nonrelationshipofclimatologic factorsandpainfulsicklecellanemiacrisis.JChronicDis. 1986;39(2):121–6.

29.JonesS,DuncanER,ThomasN,WaltersJ,DickMC,HeightSE, etal.Windyweatherandlowhumidityareassociatedwith anincreasednumberofhospitaladmissionsforacutepain andsicklecelldiseaseinanurbanenvironmentwitha maritimetemperateclimate.BrJHaematol.2005;131(4): 530–3.

30.NolanVG,ZhangY,LashT,SebastianiP,SteinbergMH. Associationbetweenwindspeedandtheoccurrenceofsickle cellacutepainfulepisodes:resultsofacase-crossoverstudy. BrJHaematol.2008;143(3):433–8.

31.WestDC,RomanoPS,AzariR,RudominerA,HolmanM, SandhuS.Impactofenvironmentaltobaccosmokeon childrenwithsicklecelldisease.ArchPediatrAdolescMed. 2003;157(12):1197–201.

32.GlassbergJ,SpiveyJF,StrunkR,BoslaughS,DeBaunMR. Painfulepisodesinchildrenwithsicklecelldiseaseand asthmaaretemporallyassociatedwithrespiratory symptoms.JPediatrHematolOncol.2006;28(8):481–5.

33.HargraveDR,WadeA,EvansJP,HewesDK,KirkhamFJ. Nocturnaloxygensaturationandpainfulsicklecellcrisesin children.Blood.2003;101(3):846–8.

34.NeborD,BowersA,Hardy-DessourcesMD,Knight-Madden JM,RomanaM,ReidH,etal.Frequencyofpainfulcrisesin sicklecellanemiaanditsrelationshipswiththe

sympatho-vagalbalance,bloodviscosityandinflammation. Haematologica.2011;96(11):1589–94.

35.YoongWC,TuckSM.Menstrualpatterninwomenwithsickle cellanaemiaanditsassociationwithsicklingcrises.JObstet Gynaecol.2002;22(4):399–401.

36.ZempskyWT.Evaluationandtreatmentofsicklecellpainin theemergencydepartment:pathstoabetterfuture.Clin PediatrEmergMed.2010;11(4):265–73.

37.LuffyR,GroveSK.Examiningthevalidity,reliability,and preferenceofthreepediatricpainmeasurementtoolsin African-Americanchildren.PediatrNurs.2003;29(1):54–9.

38.ZempskyWT,CorsiJM,McKayK.Painscores:aretheyusedin sicklecellpain?PediatrEmergCare.2011;27(1):27–8.

39.Frei-JonesMJ,BaxterAL,RogersZR,BuchananGR. Vaso-occlusiveepisodesinolderchildrenwithsicklecell disease:emergencydepartmentmanagementandpain assessment.JPediatr.2008;152(2):281–5.

40.SmithWR,PenberthyLT,BovbjergVE,McClishDK,RobertsJD, DahmanB,etal.Dailyassessmentofpaininadultswith sicklecelldisease.AnnInternMed.2008;148:94–101.

41.JacobE,MiaskowskiC,SavedraM,BeyerJE,TreadwellM, StylesL.Quantificationofanalgesicuseinchildrenwith sicklecelldisease.ClinJPain.2007;23(1):8–14.

42.LopezBL,FlendersP,Davis-MoonL,CorbinT,BallasSK. Clinicallysignificantdifferencesinthevisualanalogpain

scaleinacutevasoocclusivesicklecellcrisis.Hemoglobin. 2007;31(4):427–32.

43.DoylePortugalR,MorgadoLoureiroM.Evaluationofpain scaletopredicthospitaladmissioninpatientswithsicklecell disease.Haematologica.2003;88(4):ELT11.

44.SporrerKA,JacksonSM,AgnerS,LaverJ,AbboudMR.Painin childrenandadolescentswithsicklecellanemia:a

prospectivestudyutilizingself-reporting.AmJPediatr HematolOncol.1994;16(3):219–24.

45.DunlopRJ,BennettKC.Painmanagementforsicklecell disease.CochraneDatabaseSystRev.2006;(2):CD003350.

46.KavanaghPL,SprinzPG,VinciSR,BauchnrH,WangCJ. Managementofchildrenwithsicklecelldisease:a comprehensivereviewoftheliterature.Pediatrics. 2011;128(6):e1552–74.

47.OkomoU,MeremikwuMM.Fluidreplacementtherapyfor acuteepisodesofpaininpeoplewithsicklecelldisease. CochraneDatabaseSystRev.2012;6:CD005406.

48.LottenbergR,HassellKL.Anevidence-basedapproachtothe treatmentofadultswithsicklecelldisease.HematolAmSoc HematolEducProgram.2005:58–65.

49.U.S.DepartmentofHealthandHumanServices,PublicHealth

Service,NationalInstitutesofHealth,NationalHeart,Lung,

andBloodInstitute.Themanagementofsicklecelldisease.

NIHPublicationNo.02-2117;2002.Availablefrom:

https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/scmngt.pdf

[cited10.01.15][Internet].

50.BrunettaDM,CléDV,HaesTM,Roriz-FilhoJS,MorigutiJC. Manejodascomplicac¸õesagudasdadoenc¸afalciforme. Medicina(RibeirãoPreto).2010;43(3):231–7.

51.MinistériodaSaúde,InstitutoNacionaldeCâncer.Cuidados paliativosoncológicos:controledador.INCA:RiodeJaneiro; 2001.p.124.

52.WorldHealthOrganization.Cancerpainreliefandpalliative care.WorldHealthOrganizationTechinicalReportSeries804. Geneva,Switzerland:WorldHealthOrganization;1990.p. 1–75.

53.WHOguidelinesonthepharmacologicaltreatmentof persistingpaininchildrenwithmedicalillnesses.World HealthOrganization;2012.p.36–53.ISBN9789241548120.

54.SCAC(theSickleCellAdvisoryCommittee)ofGENES(The GeneticNetworkofNewYork,PuertoRicoandtheVirgin Islands).Guidelinesforthetreatmentofpeoplewithsickle celldisease;March2002.

55.MinistériodaSaúde,SecretariadeAtenc¸ãoàSaúde, DepartamentodeAtenc¸ãoEspecializada.Manualdeeventos agudosemdoenc¸a.Brasília:EditoradoMinistériodaSaúde; 2009,50p.:il.[SérieA.NormaseManuaisTécnicos].

56.vanBeersEJ,vanTuijnCF,NieuwkerkPT,FriederichPW, VrankenJH,BiemondBJ.Patientcontrolledanalgesiaversus continuousinfusionofmorphineduringvaso-occlusivecrisis insicklecelldisease,arandomizedcontrolledtrial.AmJ Hematol.2007;82(11):955–60.

57.JacobsonSJ,KopeckyEA,JoshiP,BabulN.Randomisedtrialof oralmorphineforpainfulepisodesofsickle-celldiseasein children.Lancet.1997;350(9088):1358–61.

58.GriffinTC,McIntireD,BuchananGR.High-doseintravenous methylprednisolonetherapyforpaininchildrenand adolescentswithsicklecelldisease.NEnglJMed. 1994;330(11):733–7.

59.CabootJB,AllenJL.Pulmonarycomplicationsofsicklecell diseaseinchildren.CurrOpinPediatr.2008;20(3):279–87.

60.GladwinMT,KatoGJ,WeinerD,OnyekwereOC,DampierC, HsuL,etal.Nitricoxideforinhalationintheacutetreatment ofsicklecellpaincrisis:arandomizedcontrolledtrial.JAMA. 2011;305(9):893–902.

61.MinistériodaSaúde,SecretariadeAtenc¸ãoàSaúde,

básicasnadoenc¸afalciforme.Brasília:EditoradoMinistério daSaúde;2006.p.56[SérieA.NormaseManuaisTécnicos].

62.NationalInstituteforHealthandClinicalExcellence(NICE).

ClinicalGuideline143.Sicklecellacutepainfulepisode:

managementofanacutepainfulsicklecellepisodein

hospital;2012.Availablefrom:https://www.nice.org.

uk/guidance/cg143/resources/sickle-cell-disease-managing-acute-painful-episodes-in-hospital-35109569155525[cited

10.01.15][Internet].

63.BartolucciP,ElMurrT,Roudot-ThoravalF,HabibiA,SantinA, RenaudB,etal.Arandomized,controlledclinicaltrialof ketoprofenforsickle-celldiseasevaso-occlusivecrisesin adults.Blood.2009;114(18):3742–7.

64.AlvimRC,VianaMB,PiresMA,FranklinHM,PaulaMJ,Brito AC,etal.Inefficacyofpiracetaminthepreventionofpainful crisesinchildrenandadolescentswithsicklecelldisease. ActaHaematol.2005;113(4):228–33.

65.AlHajeriAA,FedorowiczZ,OmranA,TadmouriGO.Piracetam forreducingtheincidenceofpainfulsicklecelldiseasecrises. CochraneDatabaseSystRev.2007;(2):CD006111.

66.GoldmanRD,MounstephenW,Kirby-AllenM,FriedmanJN. Intravenousmagnesiumsulfateforvaso-occlusive episodesinsicklecelldisease.Pediatrics.2013;132(6):e 1634–1641.

67.ZipurskyA,RobieuxIC,BrownEJ,ShawD,O’BrodovichH, KellnerJD,etal.Oxygentherapyinsicklecelldisease.AmJ PediatrHematolOncol.1992;14(3):222–8.

68.RobieuxIC,KellnerJD,CoppesMJ,ShawD,BrownE,GoodC, etal.Analgesiainchildrenwithsicklecellcrisis:comparison ofintermittentopioidsvs.continuousintravenousinfusionof morphineandplacebo-controlledstudyofoxygeninhalation. PediatrHematolOncol.1992;9(4):317–26.

69.SickleCellSociety,DepartmentofHealth,UKForumon HaemoglobinDisorders.Standardsfortheclinicalcareof adultswithsicklecelldiseaseintheUK;2008.

70.TostesMA,BragaJA,LenCA.Abordagemdacrisedolorosaem crianc¸asportadorasdedoenc¸afalciforme.RevCiêncMéd Campinas.2009;18(1):47–55.

71.KeeleyK,BuchananGR.Acuteinfarctionoflongbonesin childrenwithsicklecellanemia.JPediatr.1982;101(2):170–5.

72.AmundsenTR,SiegelMJ,SiegelBA.Osteomyelitisand infarctioninsicklecellhemoglobinopathies:differentiation bycombinedtechnetiumandgalliumscintigraphy.Radiology. 1984;153(3):807–12.

73.SkaggsDL,KimSK,GreeneNW,HarrisD,MillerJH. Differentiationbetweenboneinfarctionandacute

osteomyelitisinchildrenwithsickle-celldiseasewithuseof sequentialradionuclidebone-marrowandbonescans.JBone JointSurgAm.2001;83A(12):1810–3.

74.RaoS,SolomonN,MillerS,DunnE.Scintigraphic differentiationofboneinfarctionfromosteomyelitisin childrenwithsicklecelldisease.JPediatr.1985;107(5):685–8.

75.KimHC,AlaviA,RussellMO,SchwartzE.Differentiationof boneandbonemarrowinfarctsfromosteomyelitisinsickle celldisorders.ClinNuclMed.1989;14(4):249–54.

76.KahnCEJr,RyanJW,HatfieldMK,MartinWB.Combinedbone marrowandgalliumimaging.Differentiationofosteomyelitis andinfarctioninsicklehemoglobinopathy.ClinNuclMed. 1988;13(6):443–9.

77.Sadat-AliM,al-UmranK,al-HabdanI,al-MulhimF. Ultrasonography:canitdifferentiatebetweenvasoocclusive crisisandacuteosteomyelitisinsicklecelldisease?JPediatr Orthop.1998;18(4):552–4.

78.WilliamRR,HusseinSS,JeansWD,WaliYA,LamkiZA.A prospectivestudyofsoft-tissueultrasonographyinsicklecell diseasepatientswithsuspectedosteomyelitis.ClinRadiol. 2000;55(4):307–10.

79.InusaBP,OyewoA,BrokkeF,SanthikumaranG,Jogeesvaran KH.Dilemmaindifferentiatingbetweenacuteosteomyelitis andboneinfarctioninchildrenwithsicklecelldisease:the roleofultrasound.PLOSONE.2013;8(6):e65001.

80.LonerganGJ,ClineDB,AbbondanzoSL.Sicklecellanemia. Radiographics.2001;21(4):971–94.