www.jped.com.br

REVIEW

ARTICLE

Assessment

of

acute

motor

deficit

in

the

pediatric

emergency

room

夽

Marcio

Moacyr

Vasconcelos

a,∗,

Luciana

G.A.

Vasconcelos

b,

Adriana

Rocha

Brito

aaUniversidadeFederalFluminense(UFF),HospitalUniversitárioAntônioPedro,DepartamentoMaternoInfantil,Niterói,RJ,

Brazil

bAssociac¸ãoBrasileiraBeneficentedeReabilitac¸ão(ABBR),DivisãodePediatria,RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil

Received21May2017;accepted28May2017 Availableonline27July2017

KEYWORDS

Acuteweakness; Motordeficit; Guillain---Barré syndrome;

Transversemyelitis; Child

Abstract

Objectives: Thisreviewarticleaimedtopresentaclinicalapproach,emphasizingthediagnostic investigation,tochildrenandadolescentswhopresentintheemergencyroomwithacute-onset muscleweakness.

Sources: AsystematicsearchwasperformedinPubMeddatabaseduringAprilandMay2017, using the following search termsin various combinations: ‘‘acute,’’ ‘‘weakness,’’ ‘‘motor deficit,’’‘‘flaccidparalysis,’’‘‘child,’’‘‘pediatric,’’and‘‘emergency’’.Thearticleschosen for thisreview werepublishedoverthepasttenyears,from1997through2017.This study assessedthepediatricagerange,from0to18years.

Summaryofthedata: Acute motor deficit is a fairly common presentation in the pedi-atric emergency room. Patients may be categorized as having localized or diffuse motor impairment, and a precise description of clinical features is essential in order to allow a complete differential diagnosis. The two most common causes of acute flaccid paralysis in the pediatric emergency room are Guillain---Barré syndrome and transverse myeli-tis; notwithstanding, other etiologies should be considered, such as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, infectiousmyelitis,myasthenia gravis,stroke, alternatinghemiplegia of childhood,periodicparalyses,brainstemencephalitis,andfunctionalmuscleweakness. Algo-rithmsforacutelocalizedordiffuseweaknessinvestigationintheemergencysettingarealso presented.

Conclusions: The clinical skills to obtain a complete history and to perform a detailed physical examination are emphasized. An organized, logical, and stepwise diagnostic and

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:VasconcelosMM,VasconcelosLG,BritoAR.Assessmentofacutemotordeficitinthepediatricemergency room.JPediatr(RioJ).2017;93:26---35.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:mmdvascon@gmail.com(M.M.Vasconcelos).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2017.06.003

therapeutic management is essential to eventually restore patient’s well-being and full health.

PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.onbehalfofSociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.Thisisan openaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Fraquezaaguda; Déficitmotor; Síndromede Guillain---Barré; Mielitetransversa; Crianc¸a

Avaliac¸ãododéficitmotoragudonoambientedeprontosocorropediátrico

Resumo

Objetivos: Oobjetivodesteartigoderevisãoéapresentarumaabordagemclínica,enfatizando ainvestigac¸ãodiagnóstica,voltadaparacrianc¸aseadolescentesnoprontosocorrocomfraqueza musculardesurgimentoagudo.

Fontes: Foi realizada uma pesquisa sistemática na base de dados PubMed entre abril e maiode2017,utilizandoosseguintestermosdepesquisaemváriascombinac¸ões:‘‘agudo’’, ‘‘fraqueza’’,‘‘déficitmotor’’,‘‘paralisiaflácida’’,‘‘crianc¸a’’,‘‘pediátrico’’e‘‘emergência’’. Ostrabalhosescolhidosparaestarevisãoforampublicadosnosúltimosdezanos,de1997a2017. Estetrabalhoabordaafaixaetáriapediátrica,de0a18anos.

Resumodosdados: Odéficitmotoragudoéumacausarazoavelmentecomumparacrianc¸ase adolescentesprocuraremoprontosocorro.Ospacientespodemserclassificadoscomo apre-sentandodeficiênciamotoralocalizadaoudifusa,eumadescric¸ãoprecisadascaracterísticas clínicas é essencial para possibilitarum diagnóstico diferenciadocompleto. Asduas causas maiscomunsdeparalisiaflácidaagudanoprontosocorropediátricosãosíndromede Guillain-Barréemielitetransversa,independentementedeoutrasetiologiasseremconsideradas,como encefalomielitedisseminadaaguda,mieliteinfecciosa,miasteniagrave,derrame,hemiplegia alternantedainfância,paralisiaperiódica,encefalitedotroncoencefálicoefraquezamuscular funcional.Osalgoritmosdainvestigac¸ãodefraquezaagudalocalizadaoudifusanaconfigurac¸ão deemergênciatambémsãoapresentados.

Conclusões: São enfatizadas as habilidades clínicas para obter um histórico completo e realizarumexamefísicodetalhado.Ummanejodiagnósticoeterapêuticoorganizado,lógico e por etapas é essencial para eventualmente restaurar o bem-estar e a saúde total do paciente.

PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.emnomedeSociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.Este ´eum artigo OpenAccess sobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Acutemotordeficitorweaknessisafairlycommon presen-tationinthepediatricemergencyroom(ER).Acrossallage ranges, 5% of all patients visiting the ER have neurologic symptoms.1 Inthissetting, thepediatrician must be

com-fortableinperformingtheinitialworkup,assomeetiologies may be life-threatening and demand urgent care. Timely interventionsarelikelytorestorepatient’swell-beingand fullhealth.

Weakness is categorized as a negative motor sign, as well as ataxia and apraxia. It is valuable to have a firm grasp on the definition of these three negative motor signs. Weakness is defined as the inability to generate normal voluntary force in a muscle or normal voluntary torque in a joint, while ataxia is the inability to gener-ate a normal voluntarymovement trajectory that cannot beattributedtoweaknessorinvoluntarymuscleactivityin theaffectedjoints.2 Ataxicmovementsareuncoordinated

and clumsy, but there is no underlying weakness of the

involvedmuscles. Apraxia is the inability toperform pre-viouslylearnedcomplexmovements,whichisnotexplained byweakness,ataxia,orinvoluntarymotoractivity,i.e.,the motor,sensory,basalganglia,andcerebellarfunctions are intact.2 It is noteworthy that sensory weakness does not

exist.

For the purpose of this study, plegia will be used to denote complete or partial weakness,3 but the reader

is informed that strictly speaking plegia means complete paralysis andparesis implies that muscle strength is only partially affected. A common descriptor of acute weak-ness is acute flaccid paralysis, meaning that in the ER setting, paralysis is usually not accompanied by spastic-ity or other abnormal signs of central nervous system (CNS)motortracts,e.g.,hyperreflexia,clonus,orBabinski reflex.4

Methods

AsystematicsearchwasperformedinPubMeddatabase dur-ing April and May 2017, using the following search terms in various combinations: ‘‘acute,’’ ‘‘weakness,’’ ‘‘motor deficit,’’ ‘‘flaccid paralysis,’’ ‘‘child,’’ ‘‘pediatric,’’ and ‘‘emergency’’.Thearticleschosenforthisreviewwere pub-lishedoverthepasttenyears,from1997through2017.This studyassessedthepediatricagerange,from0to18years.

Clinical

features

and

differential

diagnosis

Acuteweakness may present either as a localized or dif-fuseimpairment.Aprecisedescriptionofthemotordeficit

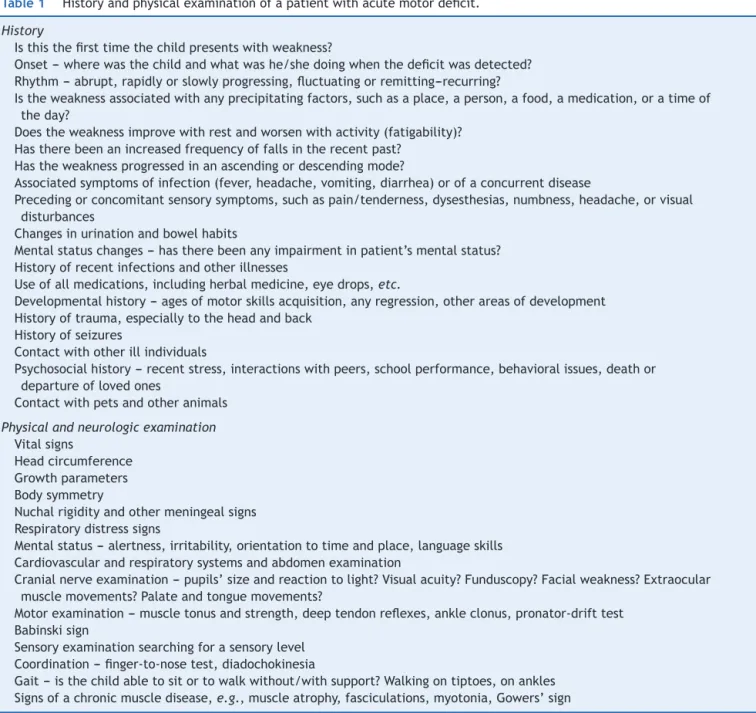

----itsmodeofonset,duration,andprogression----is essen-tialtoallowacompletedifferentialdiagnosis.Inthissense, adetailed historyandafull physical examination, includ-ingan objectiveneurologicexamination, providethebest opportunities to expedite etiology identification. Table 1

outlines the essential information to be compiled during the initial approach of a patient presenting with acute weakness.

The pattern through which weakness extends toother bodypartsmayoffercluestodiagnosis.Forexample,a rel-ativelysymmetric,ascendingdeficitsuggestsGuillain---Barré syndrome(GBS),while adescendingparalysisraises suspi-cionofbotulism.5

SomepatientswillpresenttotheERwithwhatappears to be acute weakness, but a thorough assessment will

Table1 Historyandphysicalexaminationofapatientwithacutemotordeficit.

History

Isthisthefirsttimethechildpresentswithweakness?

Onset---wherewasthechildandwhatwashe/shedoingwhenthedeficitwasdetected? Rhythm---abrupt,rapidlyorslowlyprogressing,fluctuatingorremitting---recurring?

Istheweaknessassociatedwithanyprecipitatingfactors,suchasaplace,aperson,afood,amedication,oratimeof theday?

Doestheweaknessimprovewithrestandworsenwithactivity(fatigability)? Hastherebeenanincreasedfrequencyoffallsintherecentpast?

Hastheweaknessprogressedinanascendingordescendingmode?

Associatedsymptomsofinfection(fever,headache,vomiting,diarrhea)orofaconcurrentdisease

Precedingorconcomitantsensorysymptoms,suchaspain/tenderness,dysesthesias,numbness,headache,orvisual disturbances

Changesinurinationandbowelhabits

Mentalstatuschanges---hastherebeenanyimpairmentinpatient’smentalstatus? Historyofrecentinfectionsandotherillnesses

Useofallmedications,includingherbalmedicine,eyedrops,etc.

Developmentalhistory---agesofmotorskillsacquisition,anyregression,otherareasofdevelopment Historyoftrauma,especiallytotheheadandback

Historyofseizures

Contactwithotherillindividuals

Psychosocialhistory---recentstress,interactionswithpeers,schoolperformance,behavioralissues,deathor departureoflovedones

Contactwithpetsandotheranimals

Physicalandneurologicexamination Vitalsigns

Headcircumference Growthparameters Bodysymmetry

Nuchalrigidityandothermeningealsigns Respiratorydistresssigns

Mentalstatus---alertness,irritability,orientationtotimeandplace,languageskills Cardiovascularandrespiratorysystemsandabdomenexamination

Cranialnerveexamination---pupils’sizeandreactiontolight?Visualacuity?Funduscopy?Facialweakness?Extraocular musclemovements?Palateandtonguemovements?

Motorexamination---muscletonusandstrength,deeptendonreflexes,ankleclonus,pronator-drifttest Babinskisign

Sensoryexaminationsearchingforasensorylevel Coordination---finger-to-nosetest,diadochokinesia

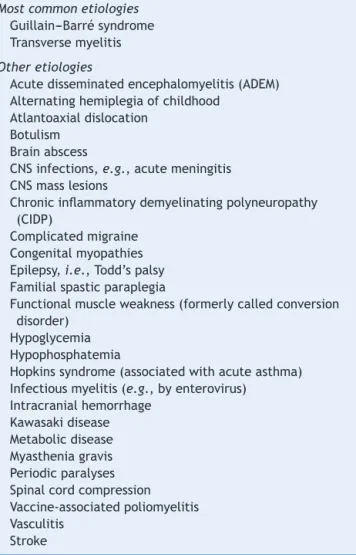

Table2 Etiologiesofanacutediffusemotordeficit.

Mostcommonetiologies Guillain---Barrésyndrome Transversemyelitis

Otheretiologies

Acutedisseminatedencephalomyelitis(ADEM) Alternatinghemiplegiaofchildhood

Atlantoaxialdislocation Botulism

Brainabscess

CNSinfections,e.g.,acutemeningitis CNSmasslesions

Chronicinflammatorydemyelinatingpolyneuropathy (CIDP)

Complicatedmigraine Congenitalmyopathies Epilepsy,i.e.,Todd’spalsy Familialspasticparaplegia

Functionalmuscleweakness(formerlycalledconversion disorder)

Hypoglycemia Hypophosphatemia

Hopkinssyndrome(associatedwithacuteasthma) Infectiousmyelitis(e.g.,byenterovirus)

Intracranialhemorrhage Kawasakidisease Metabolicdisease Myastheniagravis Periodicparalyses Spinalcordcompression Vaccine-associatedpoliomyelitis Vasculitis

Stroke

CNS,centralnervoussystem.

reveal that in fact he/she has pseudoparalysis, i.e., muscle strength is preserved and the motor function is impaired by another mechanism, most often severe pain. Common pediatrics examples of this situation are inability to walk due to calf pain secondary to acute viral myositis, pyogenic arthritis-related arthralgia (e.g., gonococcal arthritis in teenagers), nursemaid’s elbow, or bone pain secondary to osteomyelitis, bone fracture, or dislocation.

Sincetheeradicationofpoliomyelitis,thetwomost com-moncausesofacuteflaccidparalysisintheERareGBSand acutetransversemyelitis.6Amongotheretiologies(Table2),

the most relevant for the pediatric age group are acute disseminatedencephalomyelitis(ADEM),infectiousmyelitis, myastheniagravis (MG), stroke, alternating hemiplegiaof childhood,periodicparalyses,brainstem encephalitis,and functionalmuscleweakness.

Guillain---Barrésyndrome

GBS,oracuteinflammatorydemyelinating polyradiculoneu-ropathy (AIDP), is an autoimmune disease that usually

presentswithacuteonsetof arapidlyprogressive, essen-tially symmetric weakness and areflexia in a previously well child.7 The acute weakness in GBS tends to begin

distallyand to progress rostrally, and in 50---70% of cases it is preceded within four weeks by an acute respira-tory or gastrointestinal infection. The etiologic agents most frequently involved are Campylobacter jejuni and Helicobacter pylori in the gastrointestinal tract, and Mycoplasmapneumoniaeintherespiratorytract.Anannual incidenceof0.5---2casesper 100,000individuals hasbeen reportedin theage range<18 years.8 In lessthan 10% of

cases,GBS isassociatedwithvaccinationin thepreceding 30days.9

AIDPisactuallyadescriptivetermforthemostcommon clinicalpresentationofGBS,whilein10---15%ofcases,the clinicalfeaturescomprisevariantGBSforms,suchasacute motoraxonalneuropathy(AMAN,morerapidlyevolvingand moreseveremotordeficits,nosensorydeficits),acutemotor and sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN, reported nearly exclusivelyinadults),Miller-Fishersyndrome(ataxia, oph-thalmoplegia,andareflexiawithoutperipheral weakness), pharyngeal-cervical-brachial motor variant (ptosis, facial, pharyngeal,neckflexormuscleweakness),acute pandysau-tonomia,andacuteophthalmoplegia.8,10,11AMANis dueto

axonaldamageandismorefrequentlydiagnosedinAsiaand SouthAmerica.11

Clinicalonsetischaracterizedbylimbpain,limb weak-ness,andinafewcasesataxia.Physicalexaminationusually showsapreservedmentalstatusorirritabilityanddecreased orabolisheddeeptendonreflexesin weaklimbs.7,8

Weak-nessprogressesinacaudo-cranialdirection,butthereare exceptionstothispattern.Peakweaknessisusuallyreached afterseventotendays,butnolaterthanfourweeks.The severityofarmweaknessisthemostreliablefactorto pre-dictrespiratoryinsufficiency.11

The diagnosis is based on clinical findings, and sup-ported by albuminocytologic dissociation in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), that is, an increased protein level despite normalleukocytecount,aspinemagneticresonance imag-ing (MRI) showing contrast-enhancement of nerve roots, and/or demyelination or axonal damage findings in elec-tromyographywithnerve conduction studies (EMG).Some patients have normal EMG studies in the first two weeks of illness, but later on all patients show abnormal results.6

Transversemyelitis

Acutetransverse myelitis (ATM) accounts for one fifth of acquired demyelinating events in children; it hasan esti-matedannualincidenceinchildrenaged<16yearsof2per 1,000,000,anditsmale:female ratiois 1.1---1.6:1.12 There

are two peaks of pediatric incidence, at the age ranges 0---2 years and 5---17 years, with the highest incidence in theformer.13Intwo-thirdsofcases,therewasaprodromal

infectionwithinthepast30days.

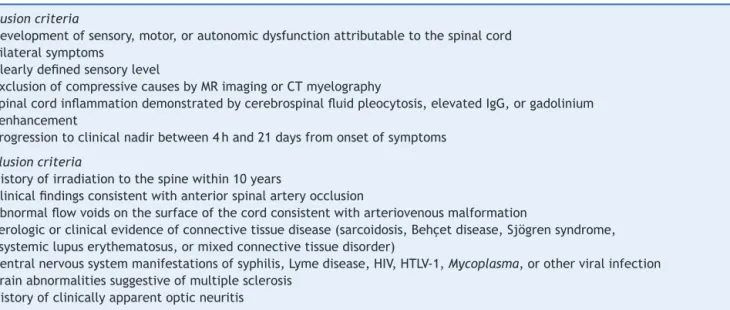

Table3 Diagnosticcriteriafortransversemyelitis.

Inclusioncriteria

Developmentofsensory,motor,orautonomicdysfunctionattributabletothespinalcord Bilateralsymptoms

Clearlydefinedsensorylevel

ExclusionofcompressivecausesbyMRimagingorCTmyelography

Spinalcordinflammationdemonstratedbycerebrospinalfluidpleocytosis,elevatedIgG,orgadolinium enhancement

Progressiontoclinicalnadirbetween4hand21daysfromonsetofsymptoms

Exclusioncriteria

Historyofirradiationtothespinewithin10years

Clinicalfindingsconsistentwithanteriorspinalarteryocclusion

Abnormalflowvoidsonthesurfaceofthecordconsistentwitharteriovenousmalformation

Serologicorclinicalevidenceofconnectivetissuedisease(sarcoidosis,Behc¸etdisease,Sjögrensyndrome, systemiclupuserythematosus,ormixedconnectivetissuedisorder)

Centralnervoussystemmanifestationsofsyphilis,Lymedisease,HIV,HTLV-1,Mycoplasma,orotherviralinfection Brainabnormalitiessuggestiveofmultiplesclerosis

Historyofclinicallyapparentopticneuritis

Source:TransverseMyelitisConsortiumWorkingGroup.Proposeddiagnosticcriteriaandnosologyofacutetransversemyelitis.14

seven days), plateau (1---26 days), and recovery phases (monthstoyears).Insomepatients,painisthepresenting feature.6

ATM is a diagnosis of exclusion;therefore, it is impor-tanttocarefullyconsideritsdifferentialdiagnoses.Inthis regard, the diagnostic criteria established by the Trans-verseMyelitisConsortium WorkingGroup maybevaluable (Table3).14

Childrenwill benefitfroma favorablemotor outcome, withupto56%havingcompleterecovery;onestudyfound thatthemeantimetorecovertheabilitytowalk indepen-dentlywas56days.6

Acutedisseminatedencephalomyelitis(ADEM)

ADEMis an inflammatory, demyelinating disease that typ-ically occurs within two days to four weeks following a viralinfectionor,lesscommonly,vaccination.15 Itpresents

withmultifocal neurologic deficits accompanied by ence-phalopathy,anditsmeanageofonsetis5.7years,witha male:femaleratioof2.3:1.15,16

Clinicalfeaturesmayincludefever,headache,vomiting, meningealsigns,visualloss,seizures,cranialnervepalsies, andmentalstatuschanges,rangingfromlethargytocoma.15

ThereisanongoingcontroversyonwhetherADEMand mul-tiplesclerosis(MS)belongtothesamediseasespectrumor are completely distinct entities.16 Although ADEM usually

followsamonophasiccourse,itsrecurringandmultiphasic variantsblursthedistinctionfromMS.BrainMRImaybethe mostvaluabletooltoaccomplishsuchdistinction,asADEM casesexhibitlargeareasofincreasedsignalintensityonT2 and FLAIR-weightedimages, with ill-defined borders, dis-tributedbilaterallyinthecerebralwhitematter(WM)and oftenaffectingthebasalganglia,brainstem,andcerebellar andcerebralcortexgraymatter,whileMScasesusuallyshow

well-definedlesionsthatareconfinedtotheperiventricular WM.17Absenceofencephalopathy,ageabove10years,

pres-ence of optic neuritis, and intrathecal oligoclonal bands duringanacuteCNSdemyelinationeventincreasetherisk ofMSdevelopment.15

CSFmaybenormalormaydisplaymildpleocytosis,with orwithoutelevatedproteinlevels.15

Early and aggressive treatment may attain good recovery with minimal or no deficit in over half the patients.18

Infectiousmyelitis

Acuteflaccidparalysiscanresultfromspinalcordinfection withanumberofpathogens,e.g.,WestNilevirus,nonpolio enteroviruses,denguevirus,syphilis,Lymedisease,human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barrvirus,HTLV-1,andMycoplasma.14,19Itsmaindistinctive

featurefromtransversemyelitisisthatthemajorityof chil-drenhavefocal,poliomyelitis-likespinalcordparalysiswith minimalornosensorysymptoms.20

Acuteviralmyositis

Acuteviralmyositismanifestsasmusclepainandlower-limb weakness,especiallyin thecalves andthighs.21 Itis most

commonlyassociatedwithinfluenzavirusinfection. Accord-ingly, its prodromal symptoms include fever, headache, cough, andother respiratory signs.Affectedchildren may refrain from moving their legs secondary to pain, or mayindeedhaveweaknessrelatedwithrhabdomyolysis.22

Myastheniagravis

MGisarelativelyrareautoimmuneneuromusculardisorder, andits presentation inchildhoodis divided intotransient neonatalMGandjuvenileMG.Theformerisdueto transpla-centaltransferofacetylcholinereceptor(AChR)antibodies andusuallyrecoverswithintwomonthsoflife.23

Clinical presentation is characterized by fatigability and fluctuating weakness of ocular, facial, limb, bulbar, andrespiratorymuscles.AntibodiesagainstAChR, muscle-specific kinase (MuSK), and lipoprotein receptor-related protein4(LRP4)mayparticipateinitspathogenesis.24

Astudycompared114ChinesejuvenileMGpatientswith 207youngadultsMGpatients.AChRantibodieswerefound in 77%, 80%, and 81% of the 0---8 years, 8---18 years, and adultageranges,respectively.Onlyoneoutofsixpatients thattestedpositiveforMuSKandLRP4antibodieswasnot an adult. Repetitivenervestimulation during electromyo-graphy(EMG) may be useful for diagnosis, aswell as the neostigmine test, but this should beperformed only in a controlledandmonitoredsetting, inthepresenceof staff whoareskilledincardiopulmonaryresuscitation.Atropine shouldbeimmediatelyavailable.23

Stroke

Strokemayoccurinchildrenolderthanonemonthas fre-quently as 13/100,000 per year. Itsincidence is higherin neonates(25to40/100,000)andishighestamongpremature infants(upto100/100,000).25 Theunderlying mechanisms

in pediatric patients include ischemic stroke, sinovenous thrombosis, and hemorrhagic stroke.26 Affected patients

usually present with an acute-onset focal neurological deficit,e.g.,hemiplegia,hemianesthesia,hemiataxia, uni-lateralfacialpalsy,and/oraphasia.27Newbornsmaypresent

withseizures.26

Of the children with arterial ischemic stroke, 20---30% will have recurrent strokes; therefore, early diagnosis is paramount.26 Appropriateinvestigationwithneuroimaging

shouldnotbedelayed.

Alternatinghemiplegiaofchildhood

Alternatinghemiplegiaof childhoodis arare developmen-taldisorderthatis caused,in75%ofcases,byamutation intheATP1A3geneofneuronalNa+/K+ATPase.28 Itsonset

is before1.5yearsof age anditsclinical featuresconsist of episodic unilateral hemiplegia, dystonia, quadriplegia, and abnormal eye movements. Each episode lasts for minutes,hours,or longer,andfrequentlyrecurs. Affected children may have developmental delay and epilepsy.28

The calcium channel blocker flunarizine can reduce fre-quency, severity,and durationof dystonicand hemiplegic spells.28

Periodicparalyses

Periodic paralyses are associated with mutations in the sodium channel gene SCN4A, the calcium channel gene

CACNA1S, or the potassium channel gene KCNJ2, and shouldnotbeconfused withsecondarycauses of episodic paralysis, such as drug toxicity.29 Patients present with

episodic attacks of flaccid muscle weakness, typically associated with hypo- or hyperkalemia. Episodes can be triggered by carbohydrate- or potassium-rich foods, or by rest after exercise. Treatment with acetazo-lamide may decrease the frequency and severity of episodes.29

Brainstemencephalitis

Bickerstaff’sbrainstemencephalitis(BBE)andMiller-Fisher syndrome form a continuous spectrum, both with ataxia andexternalophthalmoplegia,butonlythosepatientswith BBE develop impaired consciousness.30 BBE is an

uncom-mon disorder of unknown etiology; however, it is often associated with CNS cell surface antibodies, particularly anti-GQ1bantibodies.31Themostcommoninitialsymptoms

arediplopiaandgaitdisturbance;CSFalbuminocytological dissociation is found in half the patients during the sec-ond week of illness, and facial or limb weakness maybe observed.30

Spinalcordinfarction

Itisrareinchildren,andmaymimicothercommonsentities, suchasATM.AbsenceofCSFpleocytosisandanormal pro-teinlevelhelptodifferentiatebetweenthesetwoentities. It usually involves the anteriorspinal artery. Risk factors areminorspinaltrauma,parainfectiousvasculopathies,and surgery.32Childrenpresentwiththetypicalspinalcordsigns,

suchasasensorylevel,bladderand/orboweldysfunction, aswellasparaplegiaortetraplegia.

Functionalmuscleweakness

Acute weakness may be caused by functional neurologi-cal disorder (FND), a condition that was formerly called hysteriaandconversiondisorder,andchildren asyoung as 5 years of age may be affected.33 In a British study of

204 children, whose agesranged from7 to 15 years,the mostcommonpresentationwasweakness(63%)and abnor-malmovements (43%),and themost frequent antecedent stressor was bullying at school (81%).34 These authors

estimated that the annual incidence of FND in the age range<15 years was 1.30/100,000. A sharp observer will detect a few incongruous findings during physical exam-ination of a patient presenting with weakness due to FND6,33,35:

- monoculardiplopia---thechildcomplainsofdoublevision which persists when one eye is closed. Nevertheless, monocular diplopia may also be caused by a refractive error,particularlyastigmatism

Acute localized weakness

Facial palsy Monoplegia

Unilateral palsy?

Consider: •Neuroimaging for

trauma and posterior fossa tumor •Lumbar puncture for

GBS

•Detailed clinical Hx •Toxin assay and EMG

for botulism

•Previously undiagnosed Möbius syndrome No

Yes

Bell’s palsy (no further workup) Systemic symptoms or

other neurologic signs?

No

If not improved 4-6 weeks later, reconsider diagnosis Yes

Consider: • Infection workup • Otoscopy for RHS • Neuroimaging • Thyroid function

tests

• Lumbar puncture • AChR antibodies

Hx of recent trauma?

Consider: •

•

Traumatic birth → neonatal brachial plexus injury

Arm was pulled → nursemaid’s elbowa

•Compression nerve injury → acute plexopathy or neuropathy

•Sports injury to neck or shoulder → shoulder weakness due to long thoracic nerve lesion Yes

No

Consider: •Neuraxis imaging for

cerebral or spinal malformation, tumor, stroke

•EEG for subclinical seizures •EMG to classify

weakness •Hx of OPV in past 40

days for VAPP

If cause is undefined, reassess Hx & PE and

consider atypical presentations

Figure1 Algorithmforacutelocalizedweaknessinvestigationintheemergencysetting.

AChR, acetylcholine receptor; CNS, central nervous system; EEG, electroencephalography; EMG, electromyography; GBS, Guillain---Barré syndrome; Hx, history; OPV, oral polio vaccine; PE, physical examination; RHS, Ramsay-Huntsyndrome; VAPP, vaccine-associatedparalyticpoliomyelitis.aAcauseofpseudoparalysis.

- give-wayweakness---suddenloss oftoneafteraninitial good/normalstrength responsewhenamuscleis tested againstresistance

- co-contraction---effortfulcontractionofonemuscleand its agonist, resulting in almost no movement at the joint

- motorinconsistency---significantdifferencesinmotor per-formanceunderdifferenttestingconditions.

- Hoover sign --- the examiner places a hand under the heel of the ‘‘good’’ leg and asks the patient to lift the weak leg against resistance. A patient with FND will not exert downward pressure with the ‘‘good’’ leg.

Diagnostic

workup

When a pediatric patient presentsat the ER witha main complaint of acutemotor deficit, it is worthwhile topay closeattentiontoafewkeyaspectsofhistoryandphysical examination(Table1).Figs.1and2suggestalgorithmsfor investigatingacutelocalizedanddiffuseweaknessintheER setting,respectively.

A localized deficit, such as facial palsy (Table 4)36 or

monoplegia (Table 5),3 tends to have a smaller list of

etiologies, while a more diffuse deficit, e.g., paraplegia,

hemiplegia, or tetraplegia, will require consideration of manyetiologies(Table2).Awordofcautionisinorder,asa thoroughphysicalexaminationofapatientwhocomplainsof monoplegiamayrevealinconspicuousweaknessofan addi-tionallimb,sothepatientisactuallyaffectedbyhemiplegia orparaplegia.37

Whenapatientpresentswithacute-onsetdiffuse weak-ness, the presence or absence of mental status changes, i.e., encephalopathy,willguidethe diagnosticworkup. In encephalopathicpatients,CNSinfectionbecomesapressing hypothesis to be addressed by appropriatestudies. Other entities need tobe considered as well, such as seizures, mass lesions,dysfunctionin other organsystems,trauma, andmetabolicdisturbances.

Great part of the neurologic examination deals with lesion localization, and the authors believe that a gen-eral pediatrician working in the ER should master the basicexaminingskillstoascertainwhetheranacutemotor deficit stems from the brain, brainstem, spinal cord, neuromuscular junction, skeletal muscle, or peripheral nerves.

Alargenumberoftestsandproceduresareavailableto investigateanacutelyweakpatient.Asinsimilarsituations, initial priorityshouldbegiventoruleout life-threatening and treatable conditions. A stepwise, cost-effective, and timely workup is strongly recommended, as outlined in

Acute diffuse weakness

Yes Consider:

•Spine MRI for trauma, mass lesion, infarction, inflammation, or compression

•Lumbar puncture for infectious versus transverse myelitis

•Serum vitamin B12 for subacute combined degeneration

•Visual acuity assessment and serum aquaporin-4 IgG for NMO

•Findings suggestive of trauma or physical abuse

Mental status changes?

Signs of infection? Consider:

•Neuroimaging •Lumbar puncture •Infection workup •Antibiotics + acyclovir •Seizure surveillance •Assessment of other

organ systems No

Yes

Consider: •Brain MRI for ADEM/MS,

mass lesion, stroke, PRES

•EEG for Todd’s paralysis

•Anti-GQ1b and other CNS autoantibodies for brainstem encephalitis

•Assessment of other organ systems •Toxicological screening

•Findings suggestive of trauma or physical abuse •Metabolic screening Yes

No

Signs of myelopathyb?

No

Much increased CK? Acute myositis a

or other rhabdomyolysis Yes

No

Fluctuating weakness,

positive AChR? Myasthenia gravis

Areflexia, ↑CSF protein

w/o pleocytosis? GBS

Periodic paralyses

Cranial nerve deficits, constipation, descending

Botulism

Incongruous PE findings, psychosocial issues?

Functional muscle weakness Yes

Yes No

No

Reassess Hx & PE and consider atypical

↓K+, ↑K+, or ↑T 4?

Yes

No

Yes

Yes

No No Abrupt onset and consistent neuroimaging?

No

Stroke Yes

Figure2 Algorithmforacutediffuseweaknessinvestigationintheemergencysetting.

AChR,acetylcholinereceptor;CK,serumcreatine-kinase;CNS,centralnervoussystem;CSF,cerebrospinalfluid;EEG, electroen-cephalography;EMG,electromyography;GBS,Guillain---Barrésyndrome;Hx,history;IgG,immunoglobulinG;K+,serumpotassium;

MS,multiplesclerosis;NMO,neuromyelitisoptica;PE,physicalexamination;PRES,posteriorreversibleencephalopathysyndrome; RHS,Ramsay-Huntsyndrome;T4,thyroxine;w/o,without.

aAcauseofpseudoparalysis.

bMyelopathysignsincludeasensorylevel,bladderand/orboweldysfunction,andparaplegiaortetraplegia.

Table4 Etiologiesoffacialparalysis.

Congenital Acquired

Themostcommoncause

Birthtrauma Bell’spalsy

Othercauses Congenitalbilateralperisylviansyndrome

Congenitalmyasthenia Congenitalmyotonicdystrophy Facialmuscleaplasia

Facioscapulohumeralmusculardystrophy Möbiussyndrome

Transitoryneonatalmyasthenia

Acuteotitismedia

Brainstemmasslesion(e.g.,pontineglioma) Drugs:interferon,ribavirin

Facialcanalanomalousnarrowing Facialnerveschwannoma Hypoparathyroidism Hypothyroidism

Herpessimplexvirusinfection Lyme’sdisease

Melkersson-Rosenthalsyndrome Mumps

Myastheniagravis Otherinfections Ramsay-Huntsyndrome Stroke

Table5 Etiologiesofmonoplegia.

Centralnervoussystemmasslesion,includingtumor, hematomaorabscess

Complicatedmigraine Epilepsy

Headorspinaltrauma Hereditarybrachialneuritis

Hereditaryneuropathywithliabilitytopressurepalsy Neonatalbrachialplexusparalysis

Neuropathy Plexopathy Stroke

Traumaticperonealneuropathy

Vaccine-associatedparalyticpoliomyelitis

Source:AdaptedfromFenichel.3

Conclusions

MostpatientsarrivingintheERwithanacutemotordeficit will benefit from a practical investigative approach and timely interventions based upon history, physical exami-nation, and a few diagnostic tests, and will be able to eventuallyrecovertheirwell-beingandfullhealth.

Conflict

of

interests

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.Pope JV, Edlow JA. Avoiding misdiagnosis in patients with neurological emergencies. Emerg Med Int. 2012;2012: 949275.

2.SangerTD,ChenD,DelgadoMR,Gaebler-SpiraD,HallettM, MinkJW.Definitionandclassificationofnegativemotorsigns. Pediatrics.2006;118:2159---67.

3.Fenichel GM. Paraplegia and quadriplegia. In: Fenichel GM, editor. Clinical pediatric neurology: a signs and symptoms approach. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2009. p.267---83.

4.MarxA,GlassJD,SutterRW.Differentialdiagnosisofacute flac-cidparalysisanditsroleinpoliomyelitissurveillance.Epidemiol Rev.2000;22:298---316.

5.BarnesM,Britton PN,Singh-GrewalD.Of warand sausages: a case-directed review of infant botulism. J Paediatr Child Health.2013;49:E232---4.

6.MorganL.Thechildwithacuteweakness.ClinPediatrEmerg Med.2015;16:19---28.

7.RyanMM.PediatricGuillain---Barrésyndrome.CurrOpinPediatr. 2013;25:689---93.

8.Devos D, Magot A, Perrier-Boeswillwald J, Fayet G, Leclair-VisonneauL,OllivierY,etal.Guillain---Barrésyndromeduring childhood:particularclinicalandelectrophysiologicalfeatures. MuscleNerve.2013;48:247---51.

9.Top KA, Desai S, Moore D,Law BJ, Vaudry W, Halperin SA, et al. Guillain---Barré syndrome after immunization in Cana-dian children (1996---2012). Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34: 1411---3.

10.DimachkieMM,BarohnRJ.Guillain---Barrésyndromeand vari-ants.NeurolClin.2013;31:491---510.

11.Korinthenberg R. Acute polyradiculoneuritis: Guillain---Barré syndrome.In:DulacO,LassondeM,SarnatHB,editors.Handb ClinNeurol,vol.112.2013.p.1157---62.

12.Absoud M, Greenberg BM, Lim M, Lotze T, Thomas T, Deiva K. Pediatric transverse myelitis. Neurology. 2016;87: S46---52.

13.Wolf VL, Lupo PJ, Lotze TE. Pediatric acute transverse myelitis overview and differential diagnosis. JChild Neurol. 2012;27:1426---36.

14.GohC,PhalPM,DesmondPM.Neuroimaginginacutetransverse myelitis.NeuroimagClinNAm.2011;21:951---73.

15.AlperG.Acutedisseminatedencephalomyelitis.JChildNeurol. 2012;27:1408---25.

16.Wender M. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM). JNeuroimmunol.2011;231:92---9.

17.Tenembaum SN. Pediatric multiple sclerosis distinguishing clinical and MR imaging features. Neuroimag Clin N Am. 2017;27:229---50.

18.TenembaumS,ChitnisT,NessJ,HahnJS.Acutedisseminated encephalomyelitis.Neurology.2007;68:S23---36.

19.RománGC.Tropicalmyelopathies.HandbClinNeurol,vol.121; 2014.p.1521---48.

20.NelsonGR,BonkowskyJL,DollE,GreenM,HedlundGL,Moore KR,etal.Recognitionandmanagementofacuteflaccidmyelitis inchildren.PediatrNeurol.2016;55:17---21.

21.CardinSP,MartinJG,Saad-MagalhãesC.Clinicalandlaboratory descriptionofaseriesofcasesofacuteviralmyositis.JPediatr (RioJ).2015;91:442---7.

22.ChenCY,LinYR,ZhaoLL,YangWC,ChangYJ,WuKH.Clinical spectrumofrhabdomyolysispresentedtopediatricemergency department.BMCPediatr.2013;13:134.

23.LiewWK,KangPB.Updateonjuvenilemyastheniagravis.Curr OpinPediatr.2013;25:694---700.

24.Hong Y, Skeie GO, Zisimopoulou P, Karagiorgou K, Tzartos SJ,GaoX, etal.Juvenile-onsetmyastheniagravis: autoanti-bodystatus,clinicalcharacteristicsandgeneticpolymorphisms. JNeurol.2017;264:955---62.

25.RivkinMJ,BernardTJ,DowlingMM,Amlie-LefondC.Guidelines forurgentmanagementofstrokeinchildren.PediatrNeurol. 2016;56:8---17.

26.Bowers KJ, deVeber GA,Ferriero DM, Roach ES, Vexler ZS, MariaBL.Cerebrovasculardiseaseinchildren:recentadvances in diagnosis and management. J Child Neurol. 2011;26: 1074---100.

27.BernardTJ,FriedmanNR,StenceNV,JonesW,IchordR, Amlie-LefondC,etal.Preparingfora‘‘pediatricstrokealert’’.Pediatr Neurol.2016;56:18---24.

28.MasoudM,PrangeL,WuchichJ,HunanyanA,MikatiMA. Diagno-sisandtreatmentofalternatinghemiplegiaofchildhood.Curr TreatOptionsNeurol.2017;19:8.

29.StatlandJM,BarohnRJ.Musclechannelopathies:the nondys-trophicmyotoniasandperiodicparalyses.Continuum(Minneap Minn).2013;19:1598---614.

30.ItoM,KuwabaraS,OdakaM,MisawaS,KogaM,HirataK,etal. Bickerstaff’sbrainstemencephalitisandFishersyndromeform acontinuousspectrum:clinicalanalysisof581cases.JNeurol. 2008;255:674---82.

31.Hacohen Y, Nishimoto Y, Fukami Y, Lang B, Waters P, Lim MJ, et al. Paediatric brainstem encephalitis associated withglialandneuronalautoantibodies.DevMedChildNeurol. 2016;58:836---41.

32.SorteDE,PorettiA,NewsomeSD,BoltshauserE,HuismanTA, Izbudak I. Longitudinally extensive myelopathy in children. PediatrRadiol.2015;45:244---57.

34.Ani C, Reading R, Lynn R, Forlee S, Garralda E. Incidence and12-monthoutcome ofnon-transientchildhoodconversion disorder in the UK and Ireland. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202: 413---8.

35.Grattan-Smith PJ, Dale RC. Pediatric functional neurologic symptoms.HandbClinNeurol,vol.139;2016.p.489---98.

36.VasconcelosMM.Acutemotordeficit.In:VasconcelosMM, edi-tor.GPSpediatrics. RiodeJaneiro:GuanabaraKoogan;2017. p.823---8[inpress].