www.jped.com.br

REVIEW

ARTICLE

The

use

of

high-flow

nasal

cannula

in

the

pediatric

emergency

department

夽

Katherine

N.

Slain

a,b,

Steven

L.

Shein

a,b,

Alexandre

T.

Rotta

a,b,∗aUHRainbowBabies&Children’sHospital,DivisionofPediatricCriticalCareMedicine,Cleveland,UnitedStates

bCaseWesternReserveUniversity,SchoolofMedicine,DepartmentofPediatrics,Cleveland,UnitedStates

Received9May2017;accepted6June2017 Availableonline15August2017

KEYWORDS High-flownasal cannula; Children; Emergency department; Bronchiolitis

Abstract

Objectives: Tosummarizethecurrentliteraturedescribinghigh-flownasalcannulausein chil-dren,the components andmechanisms of action ofa high-flow nasal cannula system, the appropriateclinicalapplications,anditsroleinthepediatricemergencydepartment.

Sources: Acomputer-basedsearchofPubMed/MEDLINEandGoogleScholarforliteratureon high-flownasalcannulauseinchildrenwasperformed.

Datasummary: High-flownasalcannula,anon-invasiverespiratorysupportmodality,provides heatedandfullyhumidifiedgasmixturestopatientsviaanasalcannulainterface.High-flow nasalcannulalikelysupportsrespirationthoughreducedinspiratoryresistance,washoutofthe nasopharyngeal deadspace,reduced metabolicworkrelated to gasconditioning, improved airwayconductanceandmucociliaryclearance,andprovisionoflowlevelsofpositiveairway pressure.Mostdata describinghigh-flow nasalcannulauseinchildrenfocusesonthosewith bronchiolitis,althoughhigh-flow nasalcannulahasbeenusedinchildren withother respira-torydiseases.Introductionofhigh-flow nasalcannulaintoclinicalpractice, includinginthe emergencydepartment,hasbeenassociatedwithdecreasedratesofendotrachealintubation. Limitedprospectiveinterventionaldatasuggestthathigh-flownasalcannulamaybesimilarly efficaciousascontinuouspositiveairwaypressureandmoreefficaciousthanstandardoxygen therapyforsomepatients.Patientcharacteristics,suchasimprovedtachycardiaand tachyp-nea, havebeenassociated with alackofprogression toendotracheal intubation.Reported adverseeffectsarerare.

Conclusions: High-flownasal cannula shouldbeconsideredfor pediatric emergency depart-ment patients with respiratory distress not requiring immediate endotracheal intubation;

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:SlainKN,SheinSL,RottaAT.Theuseofhigh-flownasalcannulainthepediatricemergencydepartment.J

Pediatr(RioJ).2017;93:36---45.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:alex.rotta@uhhospitals.org(A.T.Rotta).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2017.06.006

0021-7557/©2017SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-ND

prospective,pediatricemergencydepartment-specifictrialsareneededtobetterdetermine responsivepatientpopulations,idealhigh-flownasalcannulasettings,andcomparativeefficacy vs.otherrespiratorysupportmodalities.

©2017SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/ 4.0/).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Cânulanasaldealto fluxo;

Crianc¸as; Departamentode emergência; Bronquiolite

Usodecânulanasaldealtofluxonodepartamentodeemergênciapediátrica

Resumo

Objetivos: Resumiraliteratura atualque descreve ouso dacânula nasal de alto fluxoem crianc¸as,os componentes emecanismosde ac¸ão dosistema decânula nasal dealto fluxo, as aplicac¸ões clínicas adequadas e o papel desse sistema no departamentode emergência pediátrico.

Fontes: Realizamosuma pesquisainformatizada naPubMed/MEDLINE e utilizamos oGoogle Acadêmicoparaencontrarliteraturasobreousodacânulanasaldealtofluxoemcrianc¸as.

Resumodosdados: Acânulanasaldealtofluxo,modalidadedesuporterespiratórionão inva-siva,fornecemisturasdegasesaquecidasetotalmenteumidificadasparapacientespormeio deumacânulanasal.Acânulanasaldealtofluxoprovavelmenteauxiliaarespirac¸ãopormeio dareduc¸ãodaresistênciainspiratória,eliminac¸ãodoespac¸omortoanatômiconasofaríngeo, reduc¸ãodotrabalhometabólicorelacionadoaocondicionamentodegás,melhorada condutân-ciadasviasaéreasetransportemucociliarefornecimentodebaixosníveisdepressãopositiva nasviasaéreas.Amaiorpartedosdadosquedescrevemousodacânulanasaldealtofluxoem crianc¸aséfocadaemcrianc¸ascombronquiolite,emboraacânulanasaldealtofluxotenhasido usadaemcrianc¸ascomoutrascausasdedoenc¸asrespiratórias.Aintroduc¸ãodacânulanasalde altofluxonapráticaclínica,incluindoodepartamentodeemergência,foiassociadaàreduc¸ão dosíndicesdeintubac¸ãoendotraqueal.Dadosintervencionistasprospectivoslimitadossugerem queacânulanasaldealtofluxopodesertãoeficazquantoapressãopositivacontínuanasvias aéreasemaiseficazdoqueaoxigenoterapiapadrãoemalgunspacientes.Ascaracterísticas dospacientes,comomelhoradataquicardiaetaquipneia,foramassociadasaumaausênciade progressãoparaintubac¸ãoendotraqueal.Foramrarososefeitosadversosrelatados.

Conclusões: Acânulanasaldealtofluxodeveserconsideradaparapacientesdodepartamento deemergênciapediátricocominsuficiênciarespiratóriaquenãoprecisamdeintubac¸ão endo-traqueal imediata,contudo,sãonecessáriosensaios clínicos prospectivosespecíficospara o departamentodeemergênciapediátricoparadeterminarmelhoraspopulac¸õesdepacientes querespondemaotratamento,asconfigurac¸õesideaisdacânulanasaldealtofluxoeaeficácia comparadaaoutrasmodalidadesdesuporterespiratório.

©2017SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigo OpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4. 0/).

Introduction

High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) is a non-invasive respira-torysupportmodalitythatprovidesconditioned(heatedand fullyhumidified)gasmixturestopatientsviaanasalcannula interface.Thereisnouniversallyaccepteddefinitionofthe minimumflowratethatdefines‘‘high’’flow.Inneonates, high-flowmaybedefinedasflowrates≥2L/min,whereas forolderchildren,flowrates≥4---6L/minarecommonly con-sideredhigh.1---3 Overthepastdecade,HFNC systemshave

gained increasedacceptance and arenow widely utilized

tosupportcritically-illpatientsacrosstheentireage

spec-trum,fromprematureneonatestoadults.Ithasalsofound

a role across various hospital sites, including the

neona-talintensivecareunit(NICU),pediatricintensivecareunit

(PICU),medicalandsurgicalintensivecareunits(ICU),

inter-mediate care units, and, more recently, the emergency

department(ED).Arecentrandomizedcontrolledtrialhas

shown that HFNC may be superior to standard low-flow

oxygendeliveryinpreventingtreatmentfailureinchildren

withbronchiolitis,4whileother trialssupportthatHFNCis

equivalentto more traditional modalities of non-invasive

ventilationsupport, suchascontinuousorbi-levelpositive

airwaypressure(CPAPorBiPAP).5,6

Inthisarticle,theauthorsreviewtherationalefor

utiliz-ingHFNCinchildren,thebasicanatomyofaHFNCsystem,

itsmechanismsofaction, clinicalapplication, anditsrole

inthepediatricED.

Rationale

for

using

HFNC

A

B

C

Gas blender

Humidifier

Heater

Cannula Heated circuit

Warm Water flow

Cross-section of tubing

Warm Water return Breathing gas

35 21 37

Figure1 Examplesofcommerciallyavailabledevicestodeliverhigh-flownasalcannula(HFNC)support.PanelA:HFNCsystem assembledfromcommonlyavailablecomponents,includingablender,heater/humidifier,heatedcircuit,andcannula.PanelB:the Airvo2HFNCsystemshownhereasamobileunitwithairandoxygencylinders(top),andacloseupofthedigitalconsoleindicating thesettemperature,flowandoxygenconcentrationoftheinspiredgas(bottom).PanelC:thePrecisionFlowHFNCsystem(top), theinternalhumidificationcartridgeandacutoutshowingthehollow-fiberconfiguration(middle),andacutoutofthecircuitwith adiagramofthewarmwaterinsulation system(bottom).ImagescourtesyofFisher&Paykel HealthcareLimited(AandB)and VapothermInc(C).

storedasadehydratedsubstance.Prolongedadministration ofsupplementaloxygencausesdrynessandirritationofthe mucusmembranesandadverselyaffectsmucociliary clear-ance, unlesshumidification is added.7 It is routinein the

hospitalsetting for a bubble humidifier filledwith sterile

watertobeusedforthispurpose.Thesesimpleand

afford-abledevicesprovidesomelevelofhydrationtodrymedical

gases,butthishumidificationisnotadequateforgasflows

greaterthan 5L/m.7,8 When highergas flowsareutilized,

it is imperative that the gas mixture be fully saturated

withwater vaporand heated closetobody temperature,

astheairway mucosais unabletoindependently transfer

sufficientheatandhumidityatthesesupraphysiologicflow

rates.

The deliveryof high-flowtherapy ispredicated onfour

importantfeatures.

(1) ‘‘Open’’system: gasflowshouldbedeliveredthrough

acannulainterfacethatdoesnotobstructthenostrils.

Thisisakeydistinctioncomparedtopressurizedmodes

of nasal ventilation, such as CPAP and BiPAP. There

should be ample opportunity for gas leakage around

the cannula, and a standard rule is to size the nasal

cannula’s prongs tooccupy no more than 50% of the

cross-sectionalareaofeachnostril.

(2) Conditioned gas:gasmixtures deliveredthroughHFNC

should be properly heated and humidified to prevent

desiccationoftherespiratorymucosa.

(3) Highflows:HFNCshoulddelivergasmixtureflowsthat

aregreaterthanthepatient’speakinspiratoryflow,so

astopreventsignificantentrainmentofambientair

dur-inginspiration.

(4) Highvelocity:gasdeliveredathighvelocitydeeply

pen-etratestheairway,movingthesourceoffreshgascloser

tothe carina andproviding some level of respiratory

support.

Basic

anatomy

of

an

HFNC

system

AlthoughthecompositionofanHFNCsystemvariesamong medicalequipmentmanufacturers,thebasicsetupincludes thesameessentialelements:(1)asourceofpressurized oxy-genandairregulatedbyaflow-meter/blender;(2)asterile waterreservoirattachedtoanefficientheaterhumidifier; (3)aninsulatedand/orheatedcircuitthatmaintains tem-peratureandrelativehumidityoftheconditionedgasasit travelstowardthepatient;and(4)anon-occlusivecannula interface.

An HFNC system can be assembled from items com-monlyusedinrespiratorycareandwidelyavailableinmost units. These systems (Fig. 1A) are composed of a water

reservoir heated by a plate heater,such asthoseused in

mechanical ventilators,ahigh-flowblendertocontrol gas

compositionandflow,andacircuitfittedwithaheatedwire

tomaintain gas temperatureand reduce condensation.In

deliveredthroughcommercialequipmentdesigned

specifi-callyforthispurpose,suchastheAirvo2(Fisher&Paykel

HealthcareLimited,Auckland,NewZealand)(Fig.1B)orthe

PrecisionFlowsystem(VapothermInc.,Exeter,New

Hamp-shire,UnitedStates)(Fig.1C).

TheAirvo2isaversatileHFNCdevice,capableof

deliv-ering a widerange of conditioned gas flows.It comprises

a humidifier chamber resting on a plate heater, a digital

consoleforsetting gasflow(2---60L/min)andtemperature

(31,34,or37◦C),abreathingcircuitwithdualspiralheating

elementsfittedwithanintegratedtemperaturesensor,and

contoured malleable cannulas with soft prongs for added

comfort and size options ranging from small neonates to

adults.Supplemental oxygencan beblended intothe

cir-cuit and regulated throughan external flow meter, while

abuilt-inultrasonicoxygensensoranalyzesthefractionof

inspiredoxygen(FiO2)anddisplaysitonthedigitalconsole.

ThePrecisionFlowisafullyintegrateddevicethatuses

adisposablehigh-efficiencyhollow-fibercartridge

humidifi-cationsystem.Gastransitsthroughthelumenofthehollow

fiberswhileheatedwatervaporisforcedthroughitssmall

particle(0.005m)pores.An intuitivesinglebutton

inter-facecontrolsgastemperature(33---43◦

C,adjustablein1◦

C

increments),FiO2(0.21---1,adjustablein0.01increments),

andgasflow(1---40L/min).Thecartridgedesignedfor

new-borns and infants has an operational flow rangebetween

1and8L/min,while thecartridgeforchildren andadults

operatesbetween5and40L/min;bothareclearedfor

30-days continuous use ona single patient. Conditioned gas

transitsfromthedevicetothecannulainterfacethroughthe

centerlumenofaheatedwater-insulatedtubethat

main-tainsgastemperatureandminimizescondensation.Awide

arrayofcannulasizesfittheentireagespectrum,including

asingleprongcannulatopreventocclusionofthenasal

pas-sagesinsmallneonateswhoalsorequireanasoenterictube.

Mechanisms

of

action

A growing body of evidence indicates that HFNC exerts potentiallybeneficialeffectsthoughseveraldifferent mech-anisms, whichinclude: (1)reduced inspiratoryresistance, (2)washoutofthenasopharyngealanatomicaldeadspace, (3)reducedmetabolicworkrelatedtogasconditioning,(4) improved airway conductance and mucociliary clearance, and(5)provisionoflowlevelsofpositiveairwaypressure.

(1) Reduced inspiratory resistance: The nostrils and the nasalpassagesarethepointsofhighestresistanceinthe humanairway.7,9Theuseofaflowthatmeetsorexceeds

an individual’s inspiratorydemand througha properly

positionednasal cannula helps offset that inspiratory

resistance by effortlessly delivering fresh gas further

down the airway, thus bypassing the area of highest

resistanceanddecreasingtheworkofbreathing.

(2) Washoutofthenasopharyngealanatomicaldeadspace:

During normal breathing, the nasopharynx contains

carbon-dioxiderichgas atthe endof exhalation.This

gasisthenrebreathedduringthenextrespiratorycycle,

which reduces the efficiency of gas exchange. When

an HFNC system is used, the fresh gas rapidly

occu-piesthenasalcavityandpharynx,washingoutcarbon

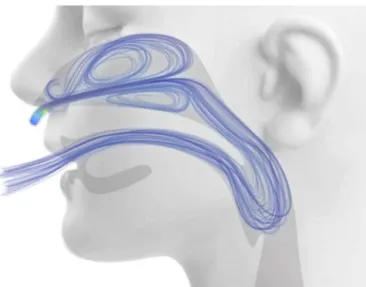

Figure2 Computationalfluiddynamicsmodelingof extratho-racicairwayflushduringhighflownasalcannulasupport.Image courtesyofThomasL.Miller,PhD.

dioxide-rich gas from the nasopharyngeal dead space viatheaforementioned‘‘open’’system(Fig.2).10 This

is equivalent to using the nasopharyngeal anatomical

dead spaceas a reservoir of fresh gas, thus reducing

rebreathingandeffectivelydecreasingthecontribution

oftheanatomicaldeadspacetobreathinginefficiency.

Therefore,apatientsupportedbyHFNCcanemploya

reduced respiratory effort and lower respiratory rate

tomaintainthesamelevelof alveolarventilationand

PaCO2.Thismechanismisparticularlyimportantinsmall

children,consideringthattheextrathoracicanatomical

deadspaceofanewbornisashighas3mL/kganddoes

notapproximatethatofanadult(0.8mL/kg)untilafter

6yearsofage.11

(3) Reduced metabolic work related to gas conditioning:

HFNCsuppliesfullyconditionedgastotheairway,thus

reducinginsensiblewaterlossesandtheenergycostof

heatingtheinspiredgastobodytemperature.10

(4) Improved airway conductance and mucociliary

clear-ance:Inhalationofheatedandhumidifiedgasprevents

desiccationofrespiratorysecretions,7decreases

dysp-neaandthesensation oforopharyngealdryness,12 and

haspotentiallysalutaryeffectsonthemucociliary

appa-ratusfunction.13,14

(5) Provision of low levels of airway pressure: HFNC

cre-ates a low level of positive pharyngeal pressure that

might assist in reducing the dynamic inspiratory

air-wayresistanceandprovidesomedegreeofcontinuous

positive airway pressure.10 The degree of observed

positive airway pressure is directly related to HFNC

flow rate, affected by mouth opening, and

depen-dentonthepressuremeasurementsite.10Threestudies

have used pressures measured in the nasopharynx as

a surrogate for lower positive end-expiration

pres-sures.Milésietal.15 studied21infants<6monthswith

bronchiolitis and found that increasing HFNC to

6---7L/minleads topharyngealpressures thatincrease

to∼6cmH2Oandareweight-dependent,withflowsof

≥2L/kg/minrequiredtoachieveapharyngealpressure

8

6

4

2

0 0 0

–2

3,0 2,5

0 2 1,5 1,0

Gas Flow (L/kg/min)

Pharyngeal Pressure (cm

H2

O)

0,5

Figure3 Relationshipbetweenpharyngealpressureandgas flowduringHFNCsupport.AdaptedfromMilésietal.15

pharyngeal pressuresof ∼3cmH2Oin 25patients with

bronchiolitis on 6---8L/min, and pressures were even

lowerifthesubject’smouthwasopen.Spentzasetal.17

reported nasopharyngeal pressures of 4---5cmH2O in

infants on 8---12L/min and pressures of ∼2cmH2O in

older patients on 20---30L/min. Pressures measured

throughanasopharyngealprobearepotentiallyaffected

by directimpression ofthe inspiredgas jetand likely

overestimatetheactualpressuretransmittedtothe

dis-tal intrathoracic airway, leading other authors touse

anesophagealballooncathetertomeasureesophageal

pressure (Pes).18---20 In one study of 11 infants with

bronchiolitis, end-expiratory Pes was ∼7cmH2O on

8L/min.20 Inanotherstudy of24infantswith

bronchi-olitisorrecoveringfromcardiacsurgery,end-expiratory

Peswas∼4cmH2Oon2L/kg/minandnotsignificantly

differentthanPesmeasuredon2L/minofflow.19

Simi-larly,astudyof25critically-illchildrenwithavarietyof

respiratorydiseasesfoundthatend-expiratoryPeswas

∼5cmH2Oon5---8L/min,only∼1cmhigherthan

mea-surementsobtainedwhileonastandardnasalcannulaat

2L/min.18 Consideredtogether,theavailableevidence

supports thetheorythat HFNC generatesverymodest

increasesinpositiveend-expiratorypressurerelativeto

standard nasalcannula,althoughtheactual amountis

dependentontheHFNC flowandpatientsize.

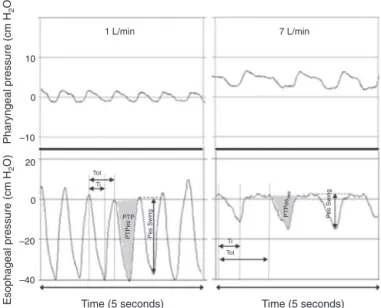

Regard-lessofmechanism,HFNChasbeenshowntosignificantly

reducetheworkofbreathing,mostlybyattenuatingthe

negativeintrathoracicinspiratorypressureasevidenced

byadecreasedesophagealpressureswings(Fig.4)and

electricalactivityofthediaphragm.15,19

Clinical

application

When initiating HFNC therapy, the clinician must control threemainvariables:gastemperature,FiO2,andflowrate. Atour institution, temperatureis typicallyset at approx-imately 1---2◦C below body temperature, and adjusted as

needed for patient comfort. In the authors’ experience, olderchildrenandyoungadultsdescribeanuncomfortable andsomewhatclaustrophobicfeelingwhengastemperature isatorabovebodytemperature,akintowhatisexperienced

1 L/min 7 L/min

10

0

–10

20

0

Tot PTP

Tot

Ti Ti

–20

–40

Time (5 seconds)

Pharyngeal pressure (cm

H2

O)

Esophageal pressure (cm

H2

O)

Time (5 seconds)

Pes Swing

PTPe

s PTPe

s

Pes Swing

Figure 4 Simultaneous recordings of pharyngeal (top) and esophageal(bottom)pressuresfromaninfantreceiving1L/min (left) and 7L/min (right) through a nasal cannula. Although there is a notable increase in pharyngeal pressure during higher flow conditions, virtually no increase is observed in end-expiratory pressure measured atthe thoracic level. The applicationof7L/minflowsignificantlydecreasedthe intratho-racicpressure swingsthroughanattenuationofthenegative inspiratorypressure.AdaptedfromMilésietal.15

while breathinginsideasteam saunaoronaveryhotand

humidsummerday.

HFNC is usually initiated with an FiO2 of 0.6 for the

hypoxemicpatient,providedtherearenophysiologic

con-traindications to the use of these high concentrations of

supplemental oxygen (e.g.,patients recovering from

Nor-woodstageIpalliationforhypoplasticleftheartsyndrome).

FiO2isthenrapidlyadjustedupordownoverthenextfew

minutestoachievethetargetoxygensaturation(SPO2),

typ-ically92%---97%.AlthoughmostpatientstreatedwithHFNC

receiveagasmixtureenrichedwithsupplementaloxygen,

thisisnotnecessarilythecaseforallpatients.Patientswith

respiratorydistresswithouthypoxemiacanstillbenefitfrom

theeffectsofHFNConrespiratorymechanicswhilereceiving

conditionedairwithouttheadditionofoxygen.

Thechoiceofgasflowrateisbasedonpatientsizeand

the perceived magnitude of respiratory support needed.

Ingeneralterms, older/largerpatientsandmoredyspneic

patientswillrequirehigherflows.Thereisnoconsensuson

idealHFNCflows.Someauthorsreportusingage-based

pro-tocols,suchas2L/minforpatients<6months,4L/minfor

6---18 monthsand 8L/min for thoseaged18---24 months21;

or 8---12L/min for infants and 20---30L/min for children.17

Othersreportweight-baseddosing,suchas1L/kg/min22or

2L/kg/min,23 and emergingdata supportthat the effects

of HFNC are dependent on weight.15 Modest support can

beinitiallyprovidedwith0.5---1.0L/kg/min,andincreasing

the flow to up to 1.5---2.0L/kg/min may further

atten-uate intrathoracic pressure swings and reduce the work

of breathing.24 Flows>2L/kg/minmaynotbe additionally

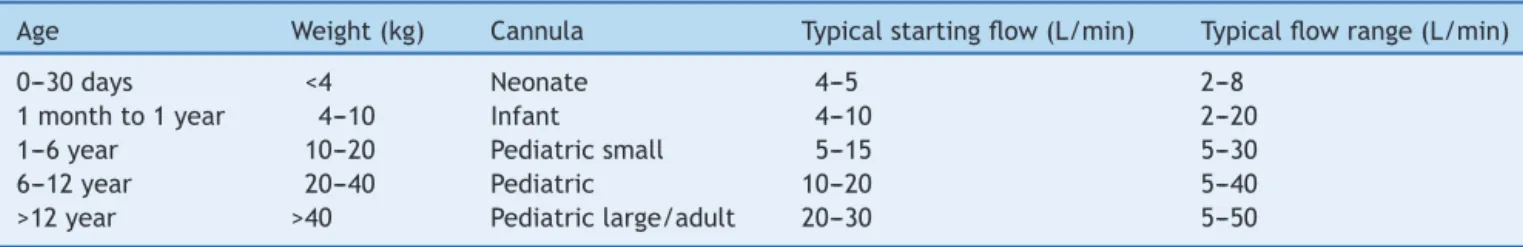

Table1 TypicalstartingflowsforinitiationofHFNCandclinicalflowrangesaccordingtoagegroupandsize.

Age Weight(kg) Cannula Typicalstartingflow(L/min) Typicalflowrange(L/min)

0---30days <4 Neonate 4---5 2---8

1monthto1year 4---10 Infant 4---10 2---20

1---6year 10---20 Pediatricsmall 5---15 5---30

6---12year 20---40 Pediatric 10---20 5---40

>12year >40 Pediatriclarge/adult 20---30 5---50

L,liters;min,minutes.

startedwithflowsof4---5L/min,whileayoungchildstarts with a flow of 5---15L/min (Table 1). Initial flow rates of

50L/min have been used in prospective studies of

criti-callyilladultsandmaybereasonableforadult-sizedPICU

patients.5

HFNC

in

the

pediatric

ED

Considering the success of HFNC in the treatment of critically-illneonates,children,andadults---especiallythe reported reduction in the need for intubation of infants with bronchiolitistreated in the PICU --- the natural next stepforclinicianswastoconsiderearlierinitiationofHFNC in patients while stillin the ED. With its broad range of potentially appropriate patient populations, ease of use, portability,andfavorablepatientsafetyandcomfortprofile, HFNCisrapidlybecominganimportantadjunctmodalityin thetreatmentof acuterespiratoryfailureinthepediatric

ED.25,26 While there is a paucity of robust pediatric

ED-specificdata, theauthorsrecommendconsidering theuse

ofHFNCininfantsandchildrenwithacutehypoxemic

res-piratoryfailurewhoneedsupportbeyondastandardnasal

cannulabutdonotrequireendotrachealintubation.HFNC

may be initiated following a failed trial of regular nasal

cannulaorasaprimaryrespiratorysupportmodality.

TheburgeoningliteraturedescribingHFNCuseinchildren

focusesprimarilyonthosewithbronchiolitis,althoughHFNC

usehasalsobeenreportedinchildrenwithothercausesof

respiratory distress, including pneumonia, asthma, croup,

andotherformsofupperairwayobstruction;neuromuscular

disease;andconvalescencefromcardiacsurgery.25---29

Sev-eralstudieshave evaluatedwhetherintroduction ofHFNC

intoclinical care wasassociated witha reducedneed for

invasive mechanical ventilation. Two small retrospective

studiesof PICUpatientswithmoderate tosevere

bronchi-olitisreportedthat makingHFNCavailable forclinicaluse

wasassociated witha decreased overall need for

intuba-tionandmechanicalventilation.27,30AlargerstudyofPICU

patientswithvariousetiologiesofrespiratorydistress

simi-larlyshowedreducedintubationratesafterintroductionof

HFNC.31 Whilethesestudiesarelimitedbytheir

retrospec-tive design and use of historical controls, similar results

werefound whenHFNC wasimplementedinthepediatric

ED.25Wingetal.studied848childrenwithacuterespiratory

insufficiencyrequiringPICUadmission.25 Overallintubation

rates decreasedfrom15.8% to8.1% (p=0.006)with

intro-ductionofHFNC andestablishmentof aguidelinefor use,

includingadecreasefrom21%to10%(p=0.03)among

chil-drenwithbronchiolitis.25 Theoverall decreasewaslargely

accountedforbyadecreasedintubationrateinthepediatric

ED,from10.5%to2.2%(p<0.001),whileratesofintubation

aftertransfertothePICUremainedsteady.25

Otherstudieshavecomparedintubationratesofchildren

treatedwithHFNCorCPAP.Inoneprospectiverandomized

controlledtrialof PICUpatients youngerthan6monthsof

agewithbronchiolitis,nodifferencewasobserved

regard-ingneedforinvasivemechanicalventilationamongsubjects

treatedwithHFNCat2L/kg/minwhencomparedwiththose

treated with CPAP at 7cmH2O, although HFNC was

asso-ciated with more frequent worsening of dyspnea.32 In a

prospectiverandomized controlledtrial of children under

5 years of age with pneumonia, subjects treated with

HFNChadsimilarratesofclinicaldeterioration,intubation,

anddeathwhencomparedwiththosetreatedwithCPAP.33

Retrospectivestudies of PICU patientswithbronchiolitis22

and varied forms of respiratory failure28 report similar

intubationrates between subjects treated withCPAP and

those receiving HFNC. However, there are no published

prospective interventional trials of pediatric ED patients

specificallydesignedtotestwhetherHFNCreducestheneed

formechanicalventilation,sothesedatashouldbe

gener-alizedtoEDpatientswithcaution.Nevertheless,duetoits

relativesafety,comfortand easeof use,the authors

rec-ommendconsideration of HFNC as a mode of respiratory

supportforchildrenpresentingtotheEDwithmoderateto

severerespiratorydistress.

Withthisstrategy,children whohavenotresponded to

HFNCandrequireahigherlevelofrespiratorysupportmust

be quickly identified. Several small retrospective studies

conducted in the pediatric ED and PICU have sought to

identifydemographicandphysiologicfactorsthatcould

dis-criminatebetweenHFNCsuccessandfailureinchildrenwith

bronchiolitis.23,26,27,34 Predictorsofsuccessincludea

signif-icantdecreaseinheartratefrombaselinewithin60minof

HFNCinitiation,23,27andsimilarlysignificantimprovementin

respiratoryrate27,34(Fig.5).Infantsandchildrenwhofailed

HFNC,variablydefinedasaneedforPICUadmission,or

esca-lationtononinvasiveorinvasiveventilation,wereyounger,26

smaller,34experiencednoimprovementinheartrate23,27or

respiratoryrate34;theywerefoundtobesickerupon

pre-sentation,withworseinitialrespiratoryrate,26 respiratory

acidosis,26,34andseverityofillnessscores.27,34

Forlessillchildren,HFNChasbeencomparedwith

stan-dardnasal cannula(NC). Inone prospectiveobservational

study of pediatric ED patients with bronchiolitis,18

chil-drenweretreatedwithHFNCand18childrenweretreated

withstandardNCbecausenoHFNCsystemwasavailable.35

Although the groups had similar baseline characteristics,

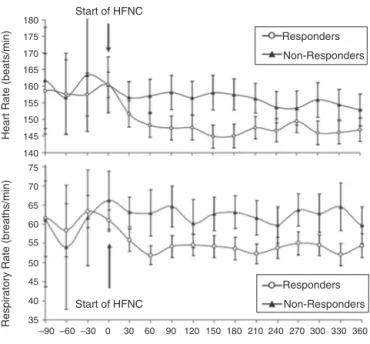

180 175 170 165 160 155 150 145 140 75 70 65 60 55 50 45 40 35 90 Time (minutes) 360 330 300 270 240 210 180 150 120 60 30 0 –30 –60 –90 Responders Non-Responders Responders Non-Responders

Start of HFNC Start of HFNC

Heart Rate (beats/min)

Respiratory Rate (breaths/min)

Figure5 Heartrate(top)andrespiratoryrate(bottom)over timeininfantswithacuteviralbronchiolitis.Anotable reduc-tion in heart rate and respiratory rate at 60min following initiation of HFNC support separates responders from non-respondersinthiscohort.AdaptedfromSchibleretal.27

andshorterdurationofhospitalization.35 Inanother

obser-vationalstudyof94bronchiolitispatientsinitiatedonHFNC

intheED,need forPICUtransferwasfour-foldlowerthan

33contemporarycontrolsreceivingstandardNCtherapy.23

Therehave alsobeenseveralinterventionaltrialsofHFNC

vs.standardNC.Inonestudy,childrenunder18monthsof

ageundergoingextubation followingcardiac surgerywere

randomizedtoHFNC at 2L/kg/minor 2L/minof standard

NC.36 HFNCwasassociated withincreasedPaO

2:FiO2 ratio

and less need for non-invasive positive pressure

ventila-tion,butnodifferenceinPaCO2orre-intubation.36Asmall

prospective pilot study of 19 children with bronchiolitis

foundnodifferenceindurationofoxygentherapyor

hospi-talizationwithHFNCvs.head-boxoxygen.37Inamuchlarger,

open,randomizedcontrolledtrialcomparingHFNCand

stan-dardNCinchildrenwithmoderatebronchiolitisadmittedto

thegeneralward,Kepreotesetal.4alsofoundnodifference

inlengthofhospitalization,durationofoxygentherapy,or

estimatedroomcostsbetweenthetwogroups.However,the

authorsestimatedthepragmatictrialdesign,whichallowed

childreninthestandardNCoxygengroupwhoexperienced

treatmentfailuretoescalatetoHFNC therapywhile

stay-ingonthegeneralcareward,wasultimatelycost-effective.

This is important, given that hospital charges associated

withbronchiolitisarerisingandeffortstowardlimitingcosts

arerecommended.38

A key factor in the cost of HFNC therapy is the

loca-tionin thehospitalin which itis provided.Many hospital

systemsonlyuse HFNC inthe EDand PICU.Other centers

have reported HFNC use on the general wards with

rea-sonablesafetyprofiles.21,23,37,39---41AllowingHFNCuseonthe

generalwardwasassociatedwithdecreasedmedianlength

of hospitalizationand totalhospital chargesin one

retro-spectivestudyofchildrenwithbronchiolitisinitiallytreated

with HFNC in the PICU.21 Reducing hospital costs by

pro-viding HFNC onthegeneral wards must bebalanced with

patient safety concerns, especially given a ∼10% rate of

eventual intubation reportedin several studies ofvarying

patientpopulations.17,21,22,26,27,30,33,34,40

When HFNC is started in the ED, consideration should

also be given tothe availabilityof portable HFNC

equip-ment, soas to avoid the need to interrupt therapy (and

the associated risk of clinical deterioration) while

trans-portingapatientfromtheEDtoaninpatientunit.Although

someofthesepatientsmight toleratethedeliveryof

non-heatednon-humidifiedgasthroughasimplecannulaoreven

interruptionofHFNCdeliveryforashortperiodoftime

dur-ing transport,theauthors prefertodeploy self-contained

portabletransportHFNCdevicesintheEDsothatpatients

can betransportedtothe inpatientsitewithout

interrup-tionsintreatment,whenneeded.

Assessment

of

clinical

response

to

HFNC

As more hospitalsand more sites withinahospital utilize HFNC,itisimperativethatusageguidelinesbedeveloped, includinghow,onwho,andwhentoinitiateHFNC,protocols fortitrationandweaning,frequencyandtypeofserial clin-icalassessment,andcleardefinitionsastowhatconstitutes treatmentfailurewiththeneedtoescalatetootherforms ofnon-invasiveventilation(CPAPorBiPAP)orendotracheal intubation.

Theclinical impactof HFNCis subjectivelyobviousthe patientwithinminutesofitsinitiation,asevidencedbythe reportsofreduceddyspneaandimprovedcomfortexpressed by adult patients and verbalchildren. Standard objective signs of clinical response, such asheart rate, respiratory rate, nasal flaring, accessorymuscle use, and SpO2, used individually or aspart of arespiratory distress score,are often used togauge clinical response to treatment. Sev-eralstudiesshowthatinitiationofHFNCisassociatedwith improvementsinrespiratoryeffortasmeasuredby improve-ments in vital signs, clinical respiratory scores, and gas exchange.17,19,30,35,39---41In theauthors’clinicalexperience,

responders can usually be discerned fromnon-responders

within 60min of initiating HFNC, and often even sooner

than that.Somecentershave attemptedtoasseswork of

breathingina moreobjectivewaythanmeredirect

clini-calobservationbymeasuringintrathoracicpressureswings

during the respiratory cycle througha pressure sensor or

balloon placed in the mid-distal intrathoracic portion of

theesophagus.15,18,24 Whenconsideredinconjunctionwith

thepatient’srespiratoryrate(pressure/rateproduct),

esti-matesofintrathoracicpressuremeasuredintheesophagus

canbeavaluabletooltoevaluateclinicalresponsetoHFNC

andevenhelptitratesupport.15,18,24However,theneedfor

insertion of the esophageal transducer and special

pres-suretransducingequipmentmostlyrelegatesthismonitoring

techniquetouseinresearch.

Patientswhoshownoclinicalimprovementorcontinue

to deteriorate despite initiation of HFNC should be

con-sidered for elective escalation of therapy (i.e., BiPAP or

cardiorespiratorycollapse. Conversely, patients who show

significantclinicalimprovementstillwarrantclose

observa-tionin amonitored environment dueto thecyclic nature

ofmanyrespiratoryconditions(i.e.,bronchiolitis)andthe

possibilitythattheimprovementobservedafterinitiationof

HFNCmightonlybetemporary.

Adverse

events

HFNC is generally safe, provided it is used within its acceptedclinicalparameters.Adverseeventsaregenerally mild, such asepistaxis, skin irritation caused by the can-nulainterface, or aerophagia. Seriousadverse events are extremelyrare,butpneumocephalushasbeenreportedin a premature neonate,42 and cases of pulmonary air leak

(i.e., pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum)43 have been

reportedin older children receiving HFNC support. These

adverse events underscore the importance of delivering

HFNCthroughan‘‘opensystem’’withaproperlysized

non-occlusivecannula thatallowsfor amplegas leakbetween

the prongs and the surrounding nostrils. An open system

ensures that the nasal cannula prongs are non-occlusive,

thus reducingtherisk of suddenincreasesin airway

pres-sureasaresultofinadvertentobstruction.Itis important

tonotethattheincidenceofpulmonaryairleakobservedin

randomizedcontrolledtrialsinvulnerablepretermneonates

wasnotdifferent between patientstreated withHFNC or

nasalCPAP.6Furthermore,theincidenceofskinbreakdown

inpatientstreatedwithHFNC wassignificantlylowerthan

inpatientstreatedwithanasalCPAPinterfacethatrequires

pressureontotheskinsurfacetocreateanocclusiveseal.6

Feeding

patients

on

HFNC

It is notuncommon for patients withrespiratory distress, especially infants with viral bronchiolitis, to have inade-quateoral intakein thehoursor evendaysleading upto theEDvisit.Inaddition,thediscomfortfromhungeroften contributes toa patient’s agitation, which can aggravate respiratory distress. Forthesereasons and thehigh value ofresumingadequatenutrition,considerationisoftengiven astowhetherornotapatientreceivingHFNCcanbefed. AlthoughthisconcernmightnotbepertinenttotheED envi-ronmentininstitutionswherepatientsonHFNCarequickly transitionedtothePICU,delaysindefinitiveplacementof apatientonHFNCmight takemany hoursor evendaysin othercenters.

Although somepractitionersconsiderHFNC usetobea contraindicationfororal feeding,ithasbeen theauthors’ personal experience that adults can swallow liquids and solids without difficulty when subjected to flows as high as40L/min. Thisgroup andothershave shownthat feed-ing selected patients on HFNC can be done safely and with few adverse events.44,45 In this institution, patients

on HFNC who have experienced significant and sustained

clinicalimprovement oftheirrespiratory distressare

gen-erallyfeed,regardlessoftheHFNCflowrate.Theauthors’

practicehasbeentodisregardHFNCasafactorinthe

deci-sion toinitiate enteralfeedsand apply thesame criteria

that wouldbe usedfor anypatient inrespiratory distress

(withorwithoutHFNC):apatientwhohasshownsufficient

improvementofvariousmarkersofrespiratorydistresswill

be tried on enteral feeds regardless of HFNC flow, while

enteralnutritionwillbewithheldfromapatientwho

con-tinuestostruggle andis at risk of requiring escalation of

support and/or aspiration. The authors believe that the

combination of HFNC supportand the comfort of enteral

feeding(for patients who meetthe criteriafor such)can

goalongwaytowardreducingthedistressexperiencedby

infants withacute viralbronchiolitis beingtreated in the

acutein-hospitalsetting.

Conclusion

HFNChasfoundawell-definedroleinthetreatmentof chil-drenwithacutehypoxemicrespiratoryfailure,bridgingthe gapbetweenthedeliveryoflow-flowsupplementaloxygen andtraditionalnon-invasiveventilation(i.e.,CPAP,BiPAP). Consideringitseaseofuse,comfort,andthegrowingbody of clinical evidence supporting its clinical equivalence to othernon-invasiveventilationmodalities,theuseofHFNC isexpectedtocontinuetoexpandbeyondtheconfinesofthe neonatalandpediatricICUs.Retrospectivedataand anec-dotalreportsshowingareductionintheneedforintubation andmechanicalventilationwhenHFNCisinitiatedintheED areencouraging,andmoredefinitivedatafromlarge ran-domizedclinicaltrialsareeagerlyawaitedtodeterminethe exactroleofHFNCinvariouspatientsubsetspresentingto thepediatricEDinrespiratorydistress.46

Conflicts

of

interest

Dr.Rottahasreceivedhonorariaforthedevelopmentof edu-cationalmaterialsandforlecturessponsoredbyVapotherm, Inc.andbyBD/Carefusion.Healsoreceivesroyaltiesfrom Elsevierforeditorialworkonapediatriccriticalcare text-book.Theotherauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.LeeJH,RehderKJ,WillifordL,CheifetzIM,TurnerDA.Useof high flownasal cannulaincriticallyill infants,children, and adults:acriticalreviewoftheliterature.IntensiveCareMed. 2013;39:247---327.

2.Beggs S, WongZH, Kaul S, OgdenKJ, Walters JA. High-flow nasalcannulatherapyforinfantswithbronchiolitis.Cochrane DatabaseSystRev.2014:CD009609.

3.MayfieldS,Jauncey-CookeJ,HoughJL,SchiblerA,GibbonsK, BogossianF.High-flownasalcannulatherapyforrespiratory sup-portinchildren.CochraneDatabaseSystRev.2014:CD009850.

4.KepreotesE,WhiteheadB,AttiaJ,OldmeadowC,CollisonA, SearlesA,etal.High-flowwarmhumidifiedoxygenversus stan-dardlow-flownasalcannulaoxygenformoderatebronchiolitis (HFWHORCT):anopen,phase4,randomisedcontrolledtrial. Lancet.2017;389:930---9.

5.FratJP,ThilleAW,MercatA,GiraultC,RagotS,PerbetS,etal. High-flowoxygenthroughnasalcannulainacutehypoxemic res-piratoryfailure.NEnglJMed.2015;372:2185---96.

7.WardJJ.High-flowoxygenadministrationbynasalcannulafor adultandperinatalpatients.RespirCare.2013;58:98---122.

8.MyersTR,AmericanAssociationforRespiratoryCare.AARC Clin-icalPracticeGuideline:selectionofanoxygendeliverydevice forneonatalandpediatricpatients---2002revision&update. RespirCare.2002;47:707---16.

9.ShepardJWJr,BurgerCD.Nasalandoralflow-volumeloopsin normalsubjectsandpatientswithobstructivesleepapnea.Am RevRespirDis.1990;142:1288---93.

10.Dysart K, Miller TL, Wolfson MR, Shaffer TH. Research in high flow therapy: mechanisms of action. Respir Med. 2009;103:1400---5.

11.NumaAH,NewthCJ.Anatomicdeadspaceininfantsand chil-dren.JApplPhysiol(1985).1996;80:1485---9.

12.RocaO,RieraJ,TorresF,MasclansJR.High-flowoxygentherapy inacuterespiratoryfailure.RespirCare.2010;55:408---13.

13.ReaH,McAuleyS,JayaramL,GarrettJ,HockeyH,StoreyL, etal.Theclinicalutilityoflong-termhumidificationtherapyin chronicairwaydisease.RespirMed.2010;104:525---33.

14.Hasani A, Chapman TH, McCool D, Smith RE, Dilworth JP, AgnewJE. Domiciliary humidificationimproveslung mucocil-iaryclearanceinpatientswithbronchiectasis.ChronRespirDis. 2008;5:81---6.

15.MilesiC,BaleineJ,MateckiS,DurandS,CombesC,NovaisAR, et al. Is treatmentwitha high flow nasal cannulaeffective inacuteviralbronchiolitis?Aphysiologicstudy.IntensiveCare Med.2013;39:1088---94.

16.Arora B, Mahajan P, Zidan MA, Sethuraman U. Nasopharyn-geal airway pressures in bronchiolitis patients treated with high-flow nasalcannulaoxygen therapy.Pediatr EmergCare. 2012;28:1179---84.

17.SpentzasT,MinarikM,PattersAB,VinsonB,StidhamG.Children withrespiratorydistresstreatedwithhigh-flownasalcannula. JIntensiveCareMed.2009;24:323---8.

18.RubinS,GhumanA,DeakersT,KhemaniR,RossP,NewthCJ. Effortofbreathinginchildrenreceivinghigh-flownasalcannula. PediatrCritCareMed.2014;15:1---6.

19.PhamTM,O’MalleyL,MayfieldS,MartinS,SchiblerA.Theeffect ofhighflownasalcannulatherapyontheworkofbreathingin infantswithbronchiolitis.PediatrPulmonol.2015;50:713---20.

20.HoughJL,PhamTM,SchiblerA.Physiologiceffectofhigh-flow nasal cannulain infantswithbronchiolitis.Pediatr Crit Care Med.2014;15:e214---9.

21.RieseJ, FierceJ,Riese A,Alverson BK.Effectofa hospital-widehigh-flownasalcannulaprotocolonclinicaloutcomesand resource utilizationofbronchiolitis patientsadmittedtothe PICU.HospPediatr.2015;5:613---8.

22.MetgeP,GrimaldiC,HassidS,ThomachotL,LoundouA,Martin C,etal.Comparisonofahigh-flowhumidifiednasalcannulato nasalcontinuouspositiveairwaypressureinchildrenwithacute bronchiolitis:experienceinapediatricintensivecareunit.Eur JPediatr.2014;173:953---8.

23.MayfieldS,BogossianF,O’MalleyL,SchiblerA.High-flownasal cannula oxygen therapy for infants with bronchiolitis: pilot study.JPaediatrChildHealth.2014;50:373---8.

24.WeilerTW,KamerkarA, HotzJ,RossPA,NewthCJ,Khemani R.High-flownasalcannulaoffersgreaterreductionofeffortof breathing inchildrenoflowerweight. AmJRespirCritCare Med.2016;193:A6347.

25.Wing R, James C,Maranda LS, ArmsbyCC. Useof high-flow nasalcannulasupportintheemergencydepartmentreducesthe needforintubationinpediatricacuterespiratoryinsufficiency. PediatrEmergCare.2012;28:1117---23.

26.KellyGS,SimonHK,SturmJJ.High-flownasalcannulausein childrenwithrespiratorydistressintheemergencydepartment: predictingtheneedforsubsequentintubation.PediatrEmerg Care.2013;29:888---92.

27.SchiblerA,PhamTM,DunsterKR,FosterK,BarlowA,Gibbons K,etal.Reducedintubationratesforinfantsafterintroduction ofhigh-flownasalprongoxygendelivery.IntensiveCareMed. 2011;37:847---52.

28.tenBrinkF,DukeT,EvansJ.High-flownasalprongoxygen ther-apyornasopharyngealcontinuouspositiveairwaypressurefor childrenwithmoderate-to-severerespiratorydistress?Pediatr CritCareMed.2013;14:e326---31.

29.MikalsenIB,DavisP,OymarK.Highflownasalcannulain chil-dren:aliteraturereview.ScandJTraumaResuscEmergMed. 2016;24:93.

30.McKiernan C, Chua LC, Visintainer PF, Allen H. High flow nasalcannulaetherapyininfantswithbronchiolitis.JPediatr. 2010;156:634---8.

31.KawaguchiA,YasuiY,deCaenA,GarrosD.Theclinicalimpact ofheatedhumidifiedhigh-flownasalcannulaonpediatric res-piratorydistress.PediatrCritCareMed.2017;18:112---9.

32.MilesiC,Essouri S, PouyauR, LietJM,AfanettiM,Portefaix A,etal.Highflownasalcannula(HFNC)versusnasal continu-ouspositiveairwaypressure(nCPAP)fortheinitialrespiratory management of acute viral bronchiolitis in young infants: a multicenterrandomizedcontrolledtrial(TRAMONTANEstudy). IntensiveCareMed.2017;43:209---16.

33.ChistiMJ,SalamMA,SmithJH,AhmedT,PietroniMA,Shahunja KM,etal.Bubblecontinuouspositiveairwaypressurefor chil-drenwithseverepneumoniaandhypoxaemiainBangladesh:an open,randomisedcontrolledtrial.Lancet.2015;386:1057---65.

34.AbboudPA,RothPJ,SkilesCL,StolfiA,RowinME.Predictorsof failureininfantswithviralbronchiolitistreatedwithhigh-flow, high-humidity nasal cannulatherapy. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:e343---9.

35.MilaniGP,PlebaniAM,ArturiE,BrusaD,EspositoS,Dell’EraL, etal.Usingahigh-flownasalcannulaprovidedsuperiorresults tolow-flowoxygendeliveryinmoderatetoseverebronchiolitis. ActaPaediatr.2016;105:e368---72.

36.TestaG,IodiceF,RicciZ,VitaleV,DeRazzaF,HaibergerR,etal. Comparativeevaluationofhigh-flownasalcannulaand conven-tionaloxygentherapyinpaediatriccardiacsurgicalpatients:a randomizedcontrolledtrial.InteractCardiovascThoracSurg. 2014;19:456---61.

37.HilliardTN,Archer N,LauraH,HeraghtyJ,CottisH,MillsK, etal.Pilotstudyofvapothermoxygendeliveryinmoderately severebronchiolitis.ArchDisChild.2012;97:182---3.

38.HasegawaK,TsugawaY,BrownDF,MansbachJM,CamargoCA Jr.TrendsinbronchiolitishospitalizationsintheUnitedStates, 2000---2009.Pediatrics.2013;132:28---36.

39.Bressan S, Balzani M,Krauss B, Pettenazzo A, Zanconato S, BaraldiE.High-flownasalcannulaoxygenforbronchiolitisina pediatricward:apilotstudy.EurJPediatr.2013;172:1649---56.

40.KallappaC, Hufton M,Millen G, Ninan TK. Use ofhigh flow nasalcannulaoxygen(HFNCO)ininfantswithbronchiolitisona paediatricward:a3-yearexperience.ArchDisChild.2014;99: 790---1.

41.DavisonM,WatsonM,WocknerL, KinnearF.Paediatric high-flow nasal cannula therapy in children withbronchiolitis: a retrospectivesafetyandefficacystudyinanon-tertiary envi-ronment.EmergMedAustralas.2017;29:198---203.

42.JasinLR,KernS,ThompsonS,WalterC,RoneJM,YohannanMD. Subcutaneousscalpemphysema,pneumo-orbitisand pneumo-cephalusinaneonateonhighhumidityhighflownasalcannula. JPerinatol.2008;28:779---81.

43.HegdeS, Prodhan P. Seriousair leak syndrome complicating high-flownasalcannulatherapy:areportof3cases.Pediatrics. 2013;131:e939---44.

45.SochetAA, McGeeJA,OctoberTW.Oralnutritioninchildren withbronchiolitisonhigh-flownasalcannulaiswelltolerated. HospPediatr.2017;7:249---55.

46.FranklinD,DalzielS,SchlapbachLJ,BablFE,OakleyE,Craig SS,etal.Earlyhighflownasalcannulatherapyinbronchiolitis,