www.jped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Brazilian

adaptation

of

the

Functioning

after

Pediatric

Cochlear

Implantation

(FAPCI):

comparison

between

normal

hearing

and

cochlear

implanted

children

夽

,

夽夽

Trissia

M.F.

Vassoler

a,b,

Mara

L.

Cordeiro

a,b,c,d,∗aFaculdadesPequenoPríncipe,Curitiba,PR,Brazil

bDepartmentofOtorhinolaryngology,HospitalInfantilPequenoPríncipe,Curitiba,PR,Brazil cNeurosciencesGroup,InstitutodePesquisaPeléPequenoPríncipe,Curitiba,PR,Brazil

dDepartmentofPsychiatryandBiobehavioralSciencesoftheDavidGeffenSchoolofMedicine,SemelInstitute forNeuroscienceandHumanBehavior,UniversityofCalifornia,LosAngeles,UnitedStates

Received10March2014;accepted11June2014 Availableonline30October2014

KEYWORDS

FAPCI; Cochlear implantation; Verbal

communication;

Normalhearing

Abstract

Objective: Enabling developmentof theability tocommunicateeffectively is theprincipal objectiveofcochlearimplantation(CI)inchildren.However,objectiveandeffectivemetrics ofcommunicationforcochlear-implantedBrazilianchildrenarelacking.TheFunctioningafter PediatricCochlearImplantation(FAPCI),aparent/caregiverreportinginstrumentdevelopedin theUnitedStates,isthefirstcommunicativeperformancescaleforevaluationofreal-world verbalcommunicativeperformanceof2-5-year-oldchildren withcochlearimplants.The pri-mary aimwastocross-culturally adaptandvalidate theBrazilian-Portugueseversionofthe FAPCI.The secondaryaimwas toconduct atrialoftheadaptedBrazilian-PortugueseFAPCI (FAPCI-BP)innormalhearing(NH)andCIchildren.

Methods: TheAmerican-EnglishFAPCIwastranslatedbyarigorousforward-backwardprocess. TheFAPCI-BPwasthenappliedtotheparentsofchildrenwithNH(n=131)andCI(n=13),2-9 yearsofage.Test-retestreliabilitywasverified.

Results: TheFAPCI-BPwasconfirmedtohaveexcellentinternalconsistency(Cronbach’salpha >0.90).TheCIgrouphadlowerFAPCIscores(58.38±22.6)thantheNHgroup(100.38±15.2; p<0.001,Wilcoxontest).

夽 Pleasecitethisarticleas:VassolerT,CordeiroML.BrazilianadaptationoftheFunctioningafterPediatricCochlearImplantation(FAPCI):

comparisonbetweennormalhearingandcochlearimplantedchildren.JPediatr(RioJ).2015;91:160---7.

夽夽

Articlerefferstomaster’sprojectofotorhinolaryngologistmedicaldoctorTrissiaVassoler,underorientationofprofessordoctorMara

LuciaCordeiro.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:mcordeiro@mednet.ucla.edu(M.L.Cordeiro). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2014.06.008

Conclusion: ThepresentresultsindicatethattheFAPCI-BPisareliableinstrument.Itcanbe used to evaluate verbalcommunicative performancein children with andwithout CI. The FAPCIiscurrentlytheonlypsychometrically-validatedinstrumentthatallowssuchmeasures incochlear-implantedchildren.

©2014SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

FAPCI;

Implantecoclear;

Comunicac¸ãoverbal;

Audic¸ãonormal

Adaptac¸ãobrasileiradoquestionárioFunctioningInventoryafterPediatricCochlear Implantation(FAPCI):comparac¸ãoentrecrianc¸ascomaudic¸ãonormalecom implantecoclear

Resumo

Objetivo: Oprincipalobjetivodoimplantecoclear(IC)emcrianc¸asépermitiro desenvolvi-mentodacapacidadedesecomunicarefetivamente.Contudo,nãoháobjetivonemparâmetros efetivosdecomunicac¸ãoparacrianc¸asbrasileirascomoimplantecoclear.OFunctioningafter PediatricCochlearImplantation(FAPCI),instrumentoderelatodospais/prestadoresde cuida-dosdesenvolvidonosEstadosUnidos,éaprimeira escaladedesempenho paraavaliac¸ãodo desempenhocomunicativoverbalnomundorealdecrianc¸asde2-5anosdeidadecomimplantes cocleares.NossoprincipalobjetivoeraadaptarevalidaraversãodoFAPCIem portuguêsdo Brasil deformatranscultural.Nossoobjetivo secundárioerarealizarumteste daversãodo FAPCI adaptadapara o portuguêsdo Brasil (FAPCI-PB)com gruposde crianc¸as comaudic¸ão normal(AN)eIC.

Métodos: OFAPCIeminglêsnorte-americanofoitraduzidoporumprocessorigorosodetraduc¸ão eretrotraduc¸ão.OFAPCI-PBfoi,então,aplicadoaospaisdascrianc¸ascomAN(N=131)eIC (N=13)de2-9anosdeidade.Foiverificadaaconfiabilidadedareaplicac¸ãodoteste.

Resultados: Confirmou-sequeoFAPCI-PBtemexcelentecoerênciainterna(alfadeCronbach >0,90).OgrupocomICapresentoumenorespontuac¸õesnoFAPCI(58,38±22,6)queogrupo comAN(100,38±15,2;p<0,001,testedeWilcoxon).

Conclusão: EssesresultadosindicamqueoFAPCI-PBéuminstrumentoconfiável.Podeser uti-lizadoparaavaliarodesempenhocomunicativoverbalemcrianc¸ascomesemIC.OFAPCIé, atualmente,oúnicoinstrumentovalidadopsicometricamentequepossibilitaessasmedic¸ões emcrianc¸ascomimplantecoclear.

©2014SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Todososdireitos reservados.

Introduction

Cochlear implantation (CI) is a treatment for

severe-to-profoundbilateralsensorioneuralhearingloss,particularly

forchildrenwithcongenitalandperilingualetiologies.1Itis

recommendedwhentraditionalhearingaids(sound ampli-fication appliances) cannot enable sound discrimination. Social communication is an essential human capacity and orallanguageisthemostusedformofcomplex communica-tion.AmpleevidencehasshownthatchildrenwhoreceiveCI ataveryyoungageareabletodevelopbetterperformance inspeechcomprehensionandproductionandachievebetter academicandsocialbehaviorthanchildrentreatedlater.2

Thereisalsoagrowingevidencethatchildrenwith severe-to-profoundbilateralhearinglosswhoreceiveCIbilaterally canperformalmostaswellaschildrenwithnormal-hearing (NH).3 Early auditory deprivation, even if partial, has a

deleterious effect on language development and on the developmentofcentralauditoryprocessingskills inyoung children.4

Enabling hearingis the firstgoal of CI.Once adequate hearinghasbeen establishedwithCI,the developmentof

oral language is expected to follow.5 Several factors can

influencetheoutcomeofCI,suchasdurationofdeafness, age at implantation, the speech rehabilitation approach applied,andhowthese factorsinteract toinfluence neu-ralplasticity.6Manyvariablesinfluencethisprocess,andit

is extremely important that physicians andspeech thera-piststrackthe performanceandprogressof CIpatientsin theareaoflanguagedevelopment.

Severalstudieshaveinvestigatedtheeffectsof implan-tationageandtheoutcomeoflanguagedevelopmentskills. Notsurprisingly,earlierimplantationhasbeendemonstrated toleadtobetterlanguageoutcomes.7,8Otherfactorsthat

playaroleinlanguagedevelopmentafterCIincludefamily involvementinrehabilitation therapy andthe educational levelofthefamily.Geersetal.9arguedthatchildrenwith

congenitaldeafnessshouldreceiveCInolaterthan2years ofage,whileelectrophysiologicalstudiesandthebrain plas-ticityliteraturedefinethecriticalperiodforCIasextending toabout3.5yearsofage.10Insuccessivestudiesofthe

long-termeffectsauditorydeprivationonlanguagedevelopment, Davidson et al.11 found that a long period of deprivation

acquisition,buthinderedsyntaxandprosodyseverely.The languagedevelopmentofchildrenwhoreceivedstimulation via sound amplificationequipment and sign language was better following CI than those who did not receive such interventions,butoutcomesareimprovedmorebyearlyCI thanbytheseinterventions.11

ElectrophysiologicalresearchbyGilleyetal.6hasshown

thatchildrenwithcongenitaldeafnesswhoreceiveCIwithin the critical maximally plastic period for central auditory pathwaydevelopmentdevelopcorticalelectricalpotentials withlatenciesthatareclosetolatenciesobservedinhearing childrenwithinsixmonthsofstimulation.6Incontrast,

chil-drenwithcongenitaldeafnesswhoreceivedCIafter7years ofageshowcorticalelectricalpotentialswithlatenciesthat areconsistentlylongerthanthoseofage-matchedchildren withNH;outcomesinchildrenwhoreceivedCIbetween3.5 yearsand7yearsofagewerehighlyvariable.Thesefindings areconsistentwithpriorneurophysiologicalandfunctional imagingstudiesinindicatingacriticalperiodfor neuroplas-ticityoftheauditorysystembeforetheageof3.5years.12,13

Families and physicians need to be able to deter-mine whether or not the objectives of CI have been met. Traditionally, clinicians have used speech percep-tion and discrimination tests to evaluate communicative capacityinchildrenfollowingCI.14However,these

measure-mentsmay not reflectthe child’s ability tocommunicate in a real-world environment with background noise and non-ideal listening conditions.15 The World Health

Orga-nization’s International Classification of Functioning (ICF) distinguishes between communicative capacity, the abil-ity to communicate in a standardized environment, and communicativeperformance,theabilitytocommunicatein real-world environments.16 Measuring communicative

per-formance after CI is very difficult, particularly in young children, and this challenge has created a demand for validatedassessmentstools.Thewidelyavailable question-nairesusedfor assessmentofcommunicativeperformance afterCIweredesignedtomeasurecommunicativecapacity, that is, the child’s ability to understand lexicon, gram-mar, and syntax.15 Examples of this type of instrument

includetheReynellDevelopmentalLanguageScales(RDLSs), the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories (MCDIs),and the Meaningful Use of Speech Scale (MUSS). TheRDLSsareusedtoassessexpressiveandreceptive lan-guage,theMCDIsareusedtoevaluatelexicaldevelopment, andtheMUSSisusedtoassessorallanguageuseinchildren withhearingimpairments.Communicativecapacitycanbe measuredin aclinicalsetting, butsuchtesting isnot suf-ficienttoestablish whetherpatients areabletousetheir communicationskills well enough tofunction in anormal socialenvironmentintheirdailylives.15

Currently,therearenoinstrumentswithreliable param-eters that can be used to evaluate the communicative performanceofpediatriccochlearimplantusersinBrazilian Portuguese.ChildrenwhohavereceivedCIinBrazilarestill evaluatedprimarilyintermsoftheresultsofauditoryand languageassessmentsappliedinanisolatedenvironment.17

Speech perception and language skills are measured by directbehavioralobservation or, morecommonly,a proxy assessment,suchastheMUSSorRDLSs,mentioned above, ortheInfant-ToddlerMeaningfulAuditoryIntegrationScale forchildrenyoungerthan24months.

To improve auditory (re)habilitation suchthat commu-nicative performance of children with CI is maximized, thereneedstobeasufficientunderstandingofthe instru-ments’functional limitations.18 The FunctioningInventory

after Pediatric Cochlear Implantation (FAPCI) instrument wasdevelopedin theUSA,in AmericanEnglish, toenable more objective evaluation of the auditory communica-tive performance of 2-5-year-old children withCI. It was designedtoprobethechild’suseofcommunicationskillsin hisorherinteractionswithlinguisticallyfluentindividuals.18

The Speech, Spatial, and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ)19isawidelyusedstructuredscalethatevaluates

hear-ing ability in everyday situations. Originally designed for adults,ithasbeenadaptedforusewithchildren,parents, andteachers.20Itiscomposedofthreesections,A,B,andC.

SectionAassessestheabilityoftheindividualtounderstand orallanguageinaquietsetting,withbackgroundnoise,in reverberantenvironments,andonthephone.SectionB eval-uateshowwell an individualperceives hisor herposition and movement awayfroma sound source. SectionC asks the individual toidentify sounds and voices withthe aim ofdeterminingwhethersoundscanbeunderstoodand seg-regatedwithease. SSQfindingsarerelevantfor receptive languageassessment, but theSSQ does not provide infor-mation about expressive language or the quality of oral languagecommunication,astheFAPCIdoes.Furthermore, the SSQ was developed for adults and then adapted to a parent/teacherversionfor proxyassessmentof 5-11-year-oldchildren,andadaptedtoaself-reportchildversionfor children over11yearsold.Hence, theSSQis notsuitable forusewithchildreninthe2-5-year-oldageband,whereas theFAPCIis.

The FAPCI models various situations of everyday life, andallows communicativeperformancetobeassessed by professionalcareprovidersorfamilymembers.18The

instru-mentconsistsof a23-itemquestionnairethatis answered byparentsorguardiansprobingthelanguagedevelopment of children with cochlear implants who are in the 2-5-year-old age band. Respondents answer questions with a five-pointscale.TheFAPCIisbeingutilizedinseveral ongo-ingNIH-fundedstudiesofpediatricCIandhasalreadybeen translatedintoGerman.21 Thereisnochildself-report

ver-sionoftheFAPCI.

Aseriesofstudiescarriedoutbythegroupthat devel-opedtheFAPCI15,22,23showedthatdespitetheestablishment

ofgoodcommunicativecapacity,childrenwithCIwerenot communicatingonparwiththeirpeersandwerestruggling tocommunicatewithorallanguageinsocialenvironments, includingschool.Therefore,theprimaryaimofthis study wastotranslate,adapt,andtestthereliabilityoftheFAPCI for use with Brazilian children. The second aim of this workwastotestthesensitivityoftheFAPCItranslatedand adapted toBrazilian Portuguese (FAPCI-BP) in the evalua-tionoflanguagedevelopmentinNHchildrenversuschildren usingCI.

Methods

Participants

This research wasapproved by the Institutional Research

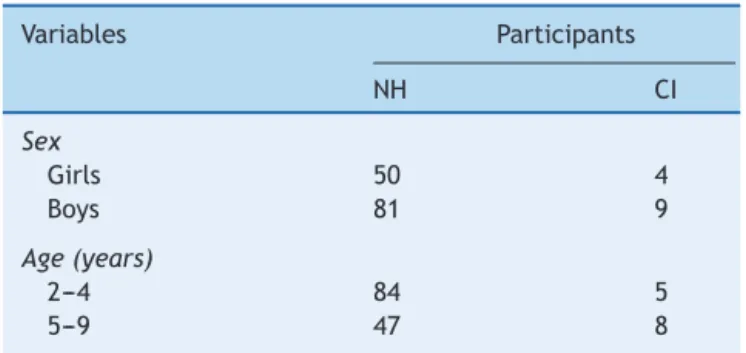

Table1 Demographicsummaryofstudysubjects.

Variables Participants

NH CI

Sex

Girls 50 4

Boys 81 9

Age(years)

2---4 84 5

5---9 47 8

NH,normalhearing;CI,cochlearimplantation.

between 2 and 9 years of age, of both sexes, who were

treated asoutpatients at the PequenoPríncipe Children’s

Hospital in the city of Curitiba, Brazil. The CI sample

included children aged 2-9 years who had undergone CI

andhadbeenlivingwithactivatedimplantsforatleastsix

months.TheNHgroupconsistedofsimilarlyagedchildren

withno otological, neurological, or neuropsychiatry

com-plaints. Parents or guardians accompanying the children

providedwritteninformedconsentandansweredthe

FAPCI-BP.Table1summarizesthedemographiccharacteristicsof thechildrenintheNHandCIgroups,andTable2detailsthe clinicalcharacteristicsoftheCIparticipants.TheFAPCI-BP wascompleted bya total of131 parents of 144children. The clinical characteristics of the 13 cochlear-implanted childrenoftheCIgrouparesummarizedinTable3.

Procedures

A two-step strategy was implemented: (1) translation,

retro-translation, and adaptation of the FAPCI; and (2)

administrationoftheFAPCI-BPtochildrenwithCIand

chil-drenwithNH.

FAPCI

The FAPCI is a 23-itemwritten questionnaire designed to

measure verbalcommunicativeperformance in children 2

to5 years of age after CI.18 It is completed by the

par-ents or theguardians ofthe subjects andcan be finished inabout5-10minutes.Therearethreeresponsemode for-mats:frequency(responselevelsnever,rarely,sometimes, often, always); quantity/proportion (number or percent-age of occurrences, e.g. 0-4%, 5-24%, 25-49%, 50-95%, or 96-100%); and examples (responses offer descriptions or examplesofbehaviors,andlevelscorrespondtoanordinal scale).15Eachanswereditemistranslatedintoascore

ran-gingfrom1point(e.g.fornever)to5points(e.g.always), regardlessofthetypeofquestion,andtheunanswered ques-tionsarescoredas0points,yieldingamaximumtotalscore of115.Ifthenumberofunansweredquestionsexceedstwo, the questionnaire is considered invalid. If more than one answerismarked,thehigheransweristaken.Meanscores werecomparedbetweenthetwogroupsandreportedwith standard deviations (SDs). This instrument wasdeveloped tocomplementothertestsofspokenlanguagecompetence toenableassessmentofcommunicativecapacityinchildren withCI.

Step1:Cross-culturaladaptationandvalidationprocess

Authorization by the original instrument’s author for the

translation,adaptation,andvalidationoftheFAPCIforthe

Brazilianpopulationwasobtained,andtheprocesswas

con-ducted in accordance with the guidelines established by

Beaton etal.24 The FAPCI was translated from English to

Portugueseby aprofessionaltranslator familiar withboth languages.Smallchangeswerenecessaryinordertoadapt theverbiagetoBrazilian culture,but theoriginalessence ofthequestionswasmaintainedasmuchaspossible. The FAPCI-BPispresentedinitsentiretyasanappendixwiththe approvalofthedevelopers.

The adapted questionnaire was sent to another pro-fessional translator who was unfamiliar with the original questionnaire for retro-translation into English.An equiv-alence of construction analysis was performed in which the original and retro-translated English versions were comparedtodeterminewhetherthereweresignificant dif-ferencesin thecontentof thequestions,thatis,whether theFAPCI-BP was faithfulto the structure of the original questionnaire.

Table2 ClinicalcharacteristicsofCIgroupparticipants.

Subject Diagnosistype AgeatCI(years) Hearingtime(years) FAPCIscore

1 Idiophatic 6.8 2.3 43

2 Genetic 3.8 2.8 87

3 Idiopathic 3.2 2.1 35

4 CongenitalRubella 4.9 1.5 67

5 Meningitis 2.1 4.7 70

6 Idiopathic 2.5 1.7 40

7 Neonatalhypoxia 1.9 1.6 88

8 Genetic 2.9 4.5 74

9 Meningitis 2.0 1.1 31

10 Idiophatic 4.4 1.4 67

11 Idiophatic 3.3 1.7 87

12 Cochlearnervehypoplasia 3.7 0.5 28

13 Idiophatic 2.0 1.1 42

Table3 ItemchangesintheadaptationoftheFAPCItoBrazilianPortuguese.

Item OriginalEnglish InitialPortuguese Adaptation FinalPortuguese

11 ...anadultnot familiarwithyour child...

...umadultonão familiarizadocoma crianc¸a...

...anadultthatdoes notknowwellyour child...

...umadultoquenão conhecebema crianc¸a... 14 ...mostly

understandable words...

...cantausando algumaspalavras inteligíveis.

...mostly comprehensible words...

...cantausandoalgumas palavrascompreensíveis.

16 Invertedquestions Questõesinvertidas Invertedquestionsdo notexistin

Portuguese

(itemomitted)

18---20 ...understandingof spokenlanguage withoutvisual...

...crianc¸ada linguagemfalada...

...understandingof spokenlanguage betweenhim/herand youwithout...

...crianc¸adalinguagem faladaentrevocêe ela...

23 How

many...commands...

Quantoscomandos falados...

How

many...commandsor orders...

Quantasordensou comandosfalados...

FAPCI,FunctioningafterPediatricCochlearImplantation.

Totestforinternalconsistency,asubgroupof34parents

ofchildrenwithNHand13parentsofchildrenwithCI

com-pletedtheFAPCI-BPtwicewithatimeintervalof atleast

twoweeks,butnotmorethanonemonth.Cronbach’salpha

wasused toverifythe internal consistency of the

instru-ment’sitemsbetweenthefirstandsecondruns.Aconstruct

canbevalidatedindirectlywithaninternalbaseof

consis-tencyor no relationbetween the questionsthat makeup

partofthescale,allowingtheconclusionthatthescalehas

avalid construction.15 Cronbach’salpha coefficient is the

simplestand best-known measure of internal consistency, andistheprimaryapproachusedinscalevalidation.In gen-eral,agroupofitemsthatexploreacommonfactorshould haveahighalphavalue.Theminimumacceptablevaluefor thealphacoefficientis0.70;alphavaluesgreaterthan0.80 arepreferable.25

Step2:ApplicabilityoftheFAPCI-BP

The FAPCI-BP was answered by parents of NH children

and parents of CI children. The results were subjected

to statistical analyses in R software, version 3.0.1 (R

Projectfor Statistical Computing, Universityof California,

CA,USA). The data wereverifiedin relation tonormality

anddescriptiveanalysesusingWilcoxontests.Comparisons

were considered significant when they had two-tailed

p-values<.001.

Results

Adaptationandinternalconsistency

After comparison of the retro-translation to the original

Englishandconsideration of culturallinguistic use,it was

determinedthat severalitems needed tobe adaptedand

oneitemneededtobewithdrawn(question16),asshown

inTable1,toobtainafinalversionoftheadapted question-nairethatwasconsistentwiththeoriginal.TheCronbach’s alphaforinternal consistency was0.948 forthe NHgroup

and0.964for theCIgroup,withnoquestionsobservedto beoutsidetheexpectedaverage,indicatingthatthe instru-menthadgoodinternalconsistency.

FAPCI-BPtrial

Comparison of the groups’ overall mean scores±SDs

revealed that the NH group performed significantly

bet-ter on the FAPCI-BP (100.38±23.5) than did the CI

group (63.00±21.0; p<.001, Wilcoxon test). The mean

scores±SDs obtainedforchildrenintheNH groupdivided

bychronologicalagearereportedinTable3togetherwith

scoredataforchildrenintheCIgroup,separatedby chrono-logicalageandthechildren’sagesatthetimehearingwas established.Themeanscoresbyageofhearingwithineach ageyearbinarepresentedasmeanswithoutSDs,sincethe subgroupsweresmallandirregular.Thegroupmediansand distributionsareillustratedinaboxplotgraphinFig.1.

Discussion

ThegoalofCIisnotonlythatchildrenwillgainfunctional

auditoryprocessingskills,butalsothattheywilldevelopthe

skills neededtocommunicateeffectivelywithspoken

lan-guage.TheFAPCIistheonlycurrentlyavailableinstrument

thatallowstheimpactofCIoncommunicationskillstobe

measuredinchildren2-5yearsold.Thepresentstudy

pro-ducedaPortuguese-languageFAPCIversionadaptedforuse

intheBrazilianpopulation(seeappendixforthefinalversion

ofFAPCI-BP).ConsistentwiththeAmerican18andGerman21

versions,theBrazilianFAPCIhadexcellentinternal consis-tency(Cronbach’salpha>0.90).Additionally,theexpected gapincommunicativeperformancewasobservedbetween childrenwithCIandchildrenwithNH.

100

80

F

APCI-BP

score

60

40

NH CI

Figure 1 Box plot of FAPCI-BP trial scores for NH and CI groups.Wilcoxon testdemonstrated thattheperformanceof thetwogroupsdifferedsignificantly.

FAPCI,FunctioningafterPediatricCochlearImplantation; NH, normalhearing;CI,cochlearimplantation.

the22-itemFAPCI-BPwassimilartothatoftheoriginal

23-itemversion,whichwasvalidatedinastudyof75families

(alpha=0.86).18,25Thealphavalueservesasanindexofan

instrument’sreliabilityinsituationswheretheresearcheris notabletoperformadditionalinterviewsoftheindividuals inquestion,butrequiresanestimateoftheaveragedegree oferror.25

Examiningthescoresbyageenabledseveralinferences to be made. Firstly, it was noticed that FAPCI-BP perfor-mancewasrelativelystableacrossageswithintheNHgroup, especiallyamongchildrenfromage3through8years.Only theyoungest(2-year-olds)andoldest(9-year-olds)had non-overlapping SDs, which is not altogether surprising given that,normally,childrenexhibitagreatlinguisticexpansion between2and3yearsofageandarestilldevelopingbasic linguistic skills. Regardless, there was at least one child withineach ageyear binachievedthe maximum possible score(115).Thegreatertheage,themorechildrenachieved the maximum possible score. Yet, even in the upper age groups, there were always some children that performed below the maximum, raisingthe question of whether the instrumentmayalsobevalidbeyondthestatedupperlimit of9yearsofage.Regardless,itshouldbenotedthatthere werequitesmallnumbersofchildrenintheage7-,8-,and 9-yearsubgroups.Thus,thedataforthosesubgroupsislikely less reliable than the data for the lower age subgroups, whichweresubstantiallylarger.

ThecomparisonofscoresbetweentheNHandCIgroups demonstratedasignificant lingeringcommunicativedeficit amongchildrenwithCI.Moreover,examiningthescoresof the individual children with CI, it is apparent that they hadnotachievedcommunicativeperformanceonparwith theirpeers,Thereareseveralfactorsthatmayaffect the abilityofchildrenwithCItoachieveoptimum-level commu-nicativeperformance, includingage ofonset ofdeafness, ageatCIactivation,useofspeechtherapy/rehabilitation, underlying pathology, and the presence of other disabili-ties, not tomention inter-individual variationin general, whichcanbesubstantial.26 Ageofimplantationappearsto

be a particularly important factor in language outcome. Childrenimplantedwhen theywere 16---24 monthsof age hadPreschoolLanguageScalescoresmatchingtheirhearing peersatages4and6.7Inthepresentstudy,onlyonechild

receivedCIbefore24monthsofage,andonlythreechildren receivedCIatapproximately24-25monthsold.The major-ityofparticipantsinthisstudyreceivedCIafter3yearsof age.Thus,thecomparisonofNHandCIgroupscanbe con-sideredpreliminary;morestudiesareneededwithalarger sampleofCIchildrenreceivingCIbefore24monthsofage. Itis expectedthatthesoonertheCIis performed,the bettertheoutcomewillbe.Thepresentstudy’sCIgroupwas quiteheterogeneousinterms ofageof CI,pathology,and hearingrehabilitation.Mostchildren inthe CIgroupwere implantedandactivatedbetween3and4yearsofage,which isconsideredborderline forthecriticalperiodofauditory pathwaydevelopmentinthebrain.Twoofthechildren(No. 5andNo.9)losttheirhearingasasequelaofmeningitisvery earlyinlife,whentheywereconsideredtobeprelingual. Thecriticalperiodforlanguagedevelopmentisthoughtto endatabout3.5yearsofagefor childrenwithcongenital deafness;childrenwhoreceivedCIaftertheirfourth birth-dayshow greater variationin outcome than children who receivedCIwhentheywereyoungerthan4yearsold.17,21

To minimize theduration of deafness and lack of crit-icalauditory stimulation, CIsurgery should be performed before2yearsofage.27,28However,evenwhenimpairment

is detected with a newborn hearing test, progression of referralstohearingspecialistsin Brazilcan bequite slow andthefrequencyofCIsperformedis inadequateinmany places(i.e.twopermonthinthestateofParaná,onlyone permonth each atthe PequenoPríncipeHospital andthe Hospital das Clínicas, personal communication). Although CIis covered by the Brazilian public health system, chil-drenneedingCIoftenhaveagedbeyondthecriticalperiod foroptimumresultsbythetimetheyreceivethe interven-tion,duetolongwaitingtimes.Newbornscreeningprograms in Brazil are also inadequate. It is particularly important forinfantstobescreenedinneonatalintensivecareunits, giventheirelevatedprevalenceof affectednewborns. For example,onestudyreportedthat,among979newbornsin anintensivecareunit,10.2%presentedwithunilateraland 4.9%presentedwithbilateralauditorybrainstemresponse impairments.29

Furthermore,afterCI,childrenshouldcommence imme-diately with auditory rehabilitation and proper speech therapy,in addition tostimulation by the family through communicative experiences. Children are subjected to a varietyoftherapies,whicharenotalwaysthemostsuitable forrehabilitationfromdeafnessandlanguagedevelopment. Speechtherapistsarenot present in every city,and even whenproperlytrainedtherapistsarepresent, often there arenotasufficientnumbertoaccommodatetheneed. More-over,it isimportant thatthetherapy beindividualized to meetthespecific needsofeach childand beofsufficient durationtoallowthechildtoabsorbthetreatment.

delayreplacement,somechildrendonotusetheirimplants throughouttheday,butratherturnthemononlywhenthey areinschool.Anotherdifficultissueforfamiliesisthecost of spareparts, such as cablesand antennas, which when damagedpreventtheuseoftheimplants,leavingchildren withoutauditorystimulation.

Thisstudyhassomelimitations.First,becausethe sam-pleof CI children was smalland heterogeneous, it is not possibletoextrapolatetheresultstoallCIchildren.Clearly, largerstudies are needed toenable multiple variables to becontrolled.Also,studiescomparingFAPCI-BPresultswith theresultsoftraditionalwidely-usedtestsoflanguageuse areneeded,sincetheFAPCI-BPisanewinstrument.In prin-ciple, itis expected that FAPCI-BPscores should increase within children with implants over time in relation to increasesincumulativetherapyandstimulationexperience, as observed with the American18 and German versions.21

Likewise,theFAPCI-BPshouldbeusefulforphonoaudilogical monitoringofpatients,particularlyinrelationtorevealing whichcommunicabilityareasmaybelagging.The aforemen-tionedlimitations notwithstanding, this study established a Brazilian version of the FAPCI with excellent internal consistency.Second, eventhough theFAPCI wasdesigned originallytotestthecommunicativeskillsofchildreninthe 2-5-year-oldageband,thisstudyincludedolderchildren,up to9yearsofage.Thiswasdoneinordertocomparetheir FAPCI-BPresultswithresultsobtainedforNHchildren, sim-ilartoprevious studiesvalidatingother versionstheFAPCI whichincludedsubjectsupto10yearsofage.21Thescores

ofthesmallnumberofchildrenover5yearsoldexamined heredidnotappeartodiffermarkedlyfromthescoresof younger children. This result is not surprising given that, normally,thebulkoffundamentallanguagedevelopmentis thoughttooccurbytheageof5years.6

In conclusion, the recently developed FAPCI-BP is the firstinstrumenttoallow functionallanguagedevelopment tobemeasuredinBrazilianchildrenusingcochlearimplants. Aftertranslationandadaption,theFAPCI-BPshowed excel-lent internal consistency and demonstratedthe expected gapbetweenNHandCIgroups,indicatingthatitisvalidfor useinBrazilianchildren.Thisworkpavesthewayforfuture studiesinBrazil,suchasapplyingtheFAPCI-BPtodevelop scoregrowthcurvesin NHchildren toserve asframework for interpreting scores in children with CI. Although the numberofsubjectswithCIinthisstudywassmall,it was possibletoestablishthattheFAPCI-BPcouldbeveryuseful toBrazilian physicians andhealthcareproviders asa reli-ablemetricofthedevelopmentofcommunicationskillsin theirCIpatients.The FAPCI-BPmay beparticularlyuseful forclarifyingdiagnosesaswellasfordirectingandrevising rehabilitativeplans, andthusbetteringtheprospectsofa goodqualityoflifeforchildrenwithCI.

Funding

Secretaria da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior do

Paraná(SETI-PR).

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgments

ThisstudywassupportedbytheDepartmentofScienceand

TechnologyoftheStateof Paraná.The authorsthank

psy-chologistCassiaBenkoforherassistance,andthechildren

andtheirfamiliesfor participatinginthestudy.Theyalso

thankDr.JohnK.Niparkoforprovidingtheopportunityto

translateandadapttheFAPCItoPortuguese.

References

1.BradhamT,JonesJ.CochlearimplantcandidacyintheUnited States:prevalenceinchildren12monthsto6yearsofage.Int JPediatrOtorhinolaryngol.2008;72:1023---8.

2.AndersonI,WeichboldV,D’HaesePS,SzuchnikJ,QuevedoMS, MartinJ,etal.Cochlearimplantationinchildrenundertheage oftwo---whatdotheoutcomesshowus?IntJPediatr Otorhino-laryngol.2004;68:425---31.

3.HyppolitoMA, BentoRF. Directions ofthe bilateralcochlear implantinBrazil.BrazJOtorhinolaryngol.2012;78:2---3. 4.Chevrie-Muller C,Narbona J, editors.linguagem dacrianc¸a:

aspectosnormaisepatológicos.2ndedPortoAlegre:Artmed;

2005.

5.Grieco-CalubTM,SaffranJR,LitovskyRY.Spokenword recogni-tionintoddlerswhousecochlearimplants.JSpeechLangHear Res.2009;52:1390---400.

6.GilleyPM,SharmaA,DormanMF.Corticalreorganizationin chil-drenwithcochlearimplants.BrainRes.2008;1239:56---65. 7.NicholasJG,GeersAE.Willtheycatchup?Theroleofageat

cochlearimplantationinthespokenlanguagedevelopmentof childrenwithseveretoprofound hearinglossJSpeechLang HearRes.2007;50:1048---62.

8.RichterB,EisseleS,LaszigR,LöhleE.Receptiveand expres-sivelanguageskillsof106childrenwithaminimumof2years’ experiencein hearingwithacochlear implant.IntJPediatr Otorhinolaryngol.2002;64:111---25.

9.GeersAE,NicholasJG, MoogJS. Estimatingtheinfluence of cochlearimplantation on languagedevelopment in children. AudiolMed.2007;5:262---73.

10.Sharma A, Dorman MF, SpahrAJ. A sensitiveperiod for the developmentofthecentralauditorysysteminchildrenwith cochlearimplants: implications for ageof implantation.Ear Hear.2002;23:532---9.

11.Davidson LS, Geers AE, Blamey PJ, Tobey EA, Brenner CA. Factorscontributingtospeechperceptionscoresinlong-term pediatriccochlearimplantusers.EarHear.2011;32:19S---26S. 12.Coez A, Zilbovicius M, Ferrary E, Bouccara D, Mosnier I,

Ambert-DahanE,etal.Cochlearimplantbenefitsindeafness rehabilitation:PETstudyoftemporalvoiceactivations.JNucl Med.2008;49:60---7.

13.EggermontJJ,PontonCW.Auditory-evokedpotentialstudiesof corticalmaturationinnormalhearingandimplantedchildren: correlationswithchangesinstructureandspeechperception. ActaOtolaryngol.2003;123:249---52.

14.Vidas S, Hassan R, Parnes LS. Real-life performance con-siderations of four pediatric multi-channel cochlear implant recipients.JOtolaryngol.1992;21:387---93.

15.ClarkJH, AggarwalP,Wang NY, Robinson R, NiparkoJK, Lin FR. Measuring communicative performance with the FAPCI instrument: preliminary results from normal hearing and cochlear implanted children. Int JPediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75:549---53.

16.WorldHealthOrganization(WHO).International classification offunctioningdisabilityandhealth.Geneva:WHO;2001. 17.SilvaMP,ComerlattoJuniorAA,BevilacquaMC,Lopes-Herrera

withacochlearimplant:asystematicreview.JApplOralSci. 2011;19:549---53.

18.Lin FR, Ceh K, Bervinchak D, Riley A, Miech R, Niparko JK. Development of a communicative performance scale for pediatric cochlear implantation. Ear Hear. 2007;28: 703---12.

19.GatehouseS, NobleW. The Speech. Spatialand Qualities of HearingScale(SSQ)IntJAudiol.2004;43:85---99.

20.GalvinKL, Noble W. Adaptation of the Speech Spatial, and Qualities of Hearing Scale for use with children, parents, and teachers. Cochlear Implants Int. 2013 [Epub ahead of print].

21.GrugelL, StreicherB, Lang-RothR, Walger M,vonWedelH, MeisterH.DevelopmentofaGermanversionofthe Function-ingAfterPediatricCochlearImplantation(FAPCI)questionnaire. HNO.2009;57:678---84.

22.Clark JH, Wang NY, Riley AW, Carson CM, Meserole RL, Lin FR,etal.Timingofcochlearimplantationandparents’global ratingsofchildren’shealth anddevelopment. OtolNeurotol. 2012;33:545---52.

23.Ganek H, McConkey Robbins A, Niparko JK. Language out-comesaftercochlearimplantation.OtolaryngolClinNorthAm. 2012;45:173---85.

24.BeatonDE,BombardierC,GuilleminF,FerrazMB.Guidelines fortheprocessofcross-culturaladaptationofself-report meas-ures.Spine(PhilaPa1976).2000;25:3186---91.

25.Cronbach LJ.Coefficientalpha and theinternal structureof test.Psychometrika.1951;16:297---334.

26.Lin FR,Wang NY,Fink NE, Quittner AL, EisenbergLS, Tobey EA,etal.Assessingtheuseofspeechandlanguagemeasures inrelationtoparentalperceptionsofdevelopmentafterearly cochlearimplantation.OtolNeurotol.2008;29:208---13. 27.Geers AE. Speech, language, and reading skills after early

cochlear implantation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:634---8.

28.BaumgartnerWD,PokSM,EgelierlerB,FranzP,GstoettnerW, HamzaviJ.Theroleofageinpediatriccochlearimplantation. IntJPediatrOtorhinolaryngol.2002;62:223---8.