Revista

Brasileira

de

Hematologia

e

Hemoterapia

Brazilian

Journal

of

Hematology

and

Hemotherapy

w w w . r b h h . o r g

Original

article

Identifying

the

similarities

and

differences

between

single

nucleotide

polymorphism

array

(SNPa)

analysis

and

karyotyping

in

acute

myeloid

leukemia

and

myelodysplastic

syndromes

Thiago

Rodrigo

de

Noronha

a,∗,

Sandra

Serson

Rohr

a,

Maria

de

Lourdes

Lopes

Ferrari

Chauffaille

a,b aUniversidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo(UNIFESP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil bGrupoFleury,SãoPaulo,Brazila

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received28August2014 Accepted26September2014 Availableonline21November2014

Keywords:

Acutemyeloidleukemia Myelodysplasticsyndromes Lossofheterozygosity

Singlenucleotidepolymorphism Karyotype

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Objective:Tostandardizethesinglenucleotidepolymorphismarray(SNPa)methodinacute myeloidleukemia/myelodysplasticsyndromes,andtoidentifythesimilaritiesand differ-encesbetweentheresultsofthismethodandkaryotyping.

Methods:Twenty-two patients diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia and three with myelodysplasticsyndromeswerestudied.TheG-bandingkaryotypingandsinglenucleotide polymorphismarrayanalysis(CytoScan®HD)wereperformedusingcellsfrombonemarrow,

DNAextractedfrommononuclearcellsfrombonemarrowandbuccalcells(BC).

Results:Themeanageofthepatientsstudiedwas54yearsold,andthemedianagewas 55years(range:28–93).Twelve(48%)weremaleand13(52%)female.Tenpatientsshowed abnormalkaryotypes(40.0%),11normal(44.0%)andfourhadnomitosis(16.0%).Regarding theresultsofbonemarrowsinglenucleotidepolymorphismarrayanalysis:17were abnor-mal (68.0%) andeight were normal(32.0%). Comparingthe two methods,karyotyping identifiedatotalof17alterations(8deletions/losses,7trissomies/gains,and2 transloca-tions)andsinglenucleotidepolymorphismarrayanalysisidentifiedatotalof42alterations (17losses,16gainsand9copy-neutrallossofheterozygosity).

Conclusion:Itispossibletostandardizesinglenucleotidepolymorphismarrayanalysisin acutemyeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndromesand compare theresults with the abnormalities detected bykaryotyping. Singlenucleotide polymorphism array analysis increasedthedetectionrateofabnormalitiescomparedtokaryotypingandalsoidentified anewsetofabnormalitiesthatdeservefurtherinvestigationinfuturestudies.

©2014Associac¸ãoBrasileiradeHematologia,HemoterapiaeTerapiaCelular.Published byElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

∗ Correspondingauthorat:UniversidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo(UNIFESP),RuaDr.DiogodeFaria,824,5◦andar,Citogenética,04037-002São

Paulo,SP,Brazil.

E-mailaddress:thinoronha@yahoo.com.br(T.R.Noronha).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjhh.2014.09.011

Introduction

Acutemyeloidleukemia(AML)isagroupofclonaldisorders resulting from acquired somatic genetic lesions accumu-lated in hematopoietic progenitors in a step-wise fashion throughout life. The mutations give rise to a malignant hematopoieticclone;malignanthematopoiesissubsequently suppressesnormalhematopoiesis.1,2

The myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a group of clonalhematopoieticstemcelldisordersinvolvingcytogenetic changes,andgenemutationsthatoccurinamultistep pro-cess, withwidespread gene hypermethylationatadvanced stages.MDS are characterizedbyineffectivehematopoiesis leadingtoblood cytopenias or,insomecases,evolution to AML.3

ThedetectionofchromosomalabnormalitiesinAML/MDS supports the diagnosis, classification, prognostic stratifi-cation, therapy option, treatment monitoring and better understanding ofthedisease’s biology.3,4 Theconsequence

of chromosomal investigations is major advances in the treatmentand survivalofpatients. However, about 50% of AML/MDS have eithernormal karyotypes or non-recurrent chromosomalabnormalities, which preventsa better char-acterization of the disease.5,6 Therefore, an increased

abnormalitydetectionratebyother methodsandimproved understandingofpathogenesisareurgentlyneeded.1,7,8

Inthiscontext,thesinglenucleotidepolymorphismarray (SNPa) method, also referred to as molecular karyotyping, is a sensitive technology used to perform high-resolution genome-wide DNA copy number analysis and to detect segmentalregionsofhomozygosity,knownasregionsof copy-neutrallossofheterozygosity(CN-LOH).2,9

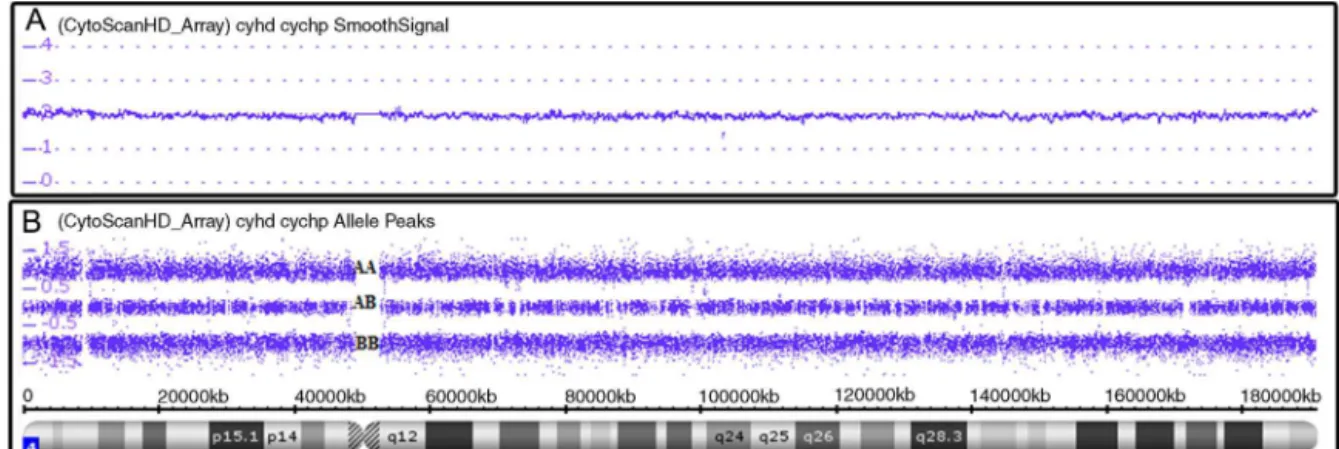

SNPa analysis uses millions of markers (probes com-prise 25-mer oligonucleotides) across the entire human genome.10 Therearetwotypesofprobes:non-polymorphic

probes,usedonlyforassessingcopynumbervariations(CNV) (Figure1A),andpolymorphicprobes,usedtoassessgenotypes (Figure1B).11Forcopynumberanalysis,patientDNAlabeled

withafluorochromeprovidessignalintensitythat,when com-paredtoasetofreferenceDNAs,indicateswhetherthereisa

gainorlossofgeneticmaterial.Forgenotypeanalysis,asingle nucleotidepolymorphism(SNP)hasasinglebasepair substi-tution(A,T,C,orG)ofonenucleotidetoanother,then,the allelescorrespondingtothenucleotidebasechangesare arbi-trarilygiventhedesignationalleleAandalleleB(polymorphic probes)andrevealwhichofthegenotypes(forexample,AA, BBorAB)ispresent.12

In order tobetter define the genetic abnormalities, the objective of this study was toidentify the similarities and differences between SNPa analysis and karyotyping in 25 AML/MDScasesatdiagnosis.

Methods

Caseselection

Twenty-five patientswithAML(n=22,non-acute promyelo-cyticleukemia)andMDS(n=3)diagnosedaccordingtoWHO criteriaattheEscolaPaulistadeMedicina,Universidade Fed-eraldeSãoPaulo(UNIFESP)fromMarch2012toJanuary2014 were studied.4 Bonemarrow (BM)aspiratewas collectedat

diagnosisfromallpatients.

At the same time, buccal cells (BC) were alsocollected (DNA-SALTMOasisDiagnostics®)todistinguishclonal abnor-malitiesfromconstitutionalfindings.13,14

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of UNIFESP and Grupo Fleury and was conducted in accor-dance with the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 2008. All patients gave informed consent prior to entering the study.

Karyotyping

ThekaryotypingwasperformedforallBMsamplesatthetime of initial diagnosis and conventional cytogenetic analyses of 24–48h cultures were performed on bone marrow aspi-ratesusingstandardtechniques.Thekaryotyperesultswere describedaccordingtotheInternationalSystemforHuman Cytogenetic Nomenclature 2009.15–17 Whenever possible,at

least20metaphaseswereanalyzed.17

Singlenucleotidepolymorphismarrayanalysis

SNPaanalysiswasperformedforallsamples(BMandBC).13

Mononuclear cellsfrom BMwere separated (Ficollmethod) and DNA was extracted from these cells as well as from BC (Nucleic Acid and Protein Purification kit from Marcherey-Nagel®).14,18DNA(250ng)wasdigested,amplified,

purified,fragmented,labeledandhybridizedusingAffymetrix CytoScan®HDArrayGeneChip;CELfileswerecreatedusing the GeneChip® System 30007G according tothe manufac-turer’sinstructions(Affymetrix).TheCELfileswereanalyzed usingChromosomeAnalysisSuitev2.0(ChAS)software.19,20

Equipment,instrumentation, andmethodologies emplo-yedduringtheuseofmicroarrayplatformswerecalibrated, monitored,andregularlymaintainedasappropriate.Positive (GenomicDNAControlsuppliedbyAffymetrix)andnegative controls (LowEDTA TE Buffer)were used tovalidate chip, reagents,andinstrumentsandeveryCytoScan®HDarrayhas internalqualitycontrolmetricsusedtodeterminepass/failfor individualsamples.21

RegionsofCNVlargerthan1MbandCN-LOHlargerthan 10MbidentifiedbytheChASSoftwareordetectedbyvisual inspection,regardlessofgenecontent,are denotedastrue aberrations,withtheexceptionofthoseknowntobenormal genomicvariants(presentintheGenomicVariantsDatabase [http://projects.tcag.ca/variation]) and/or found in constitu-tional(BC)SNPaanalysis.9,18,22,23

SNParesultsofBCindicatethe individualconstitutional genome.Thus,changesobservedinBMandnotfoundinBC areindicativeofacquiredabnormalitiesandwereconsidered forevaluation.13

Results

Themeanageofthepatientswas54yearsandthemedianage was55years(range:28–93).Twelvepatients(48%)weremale and13(52%)werefemale.

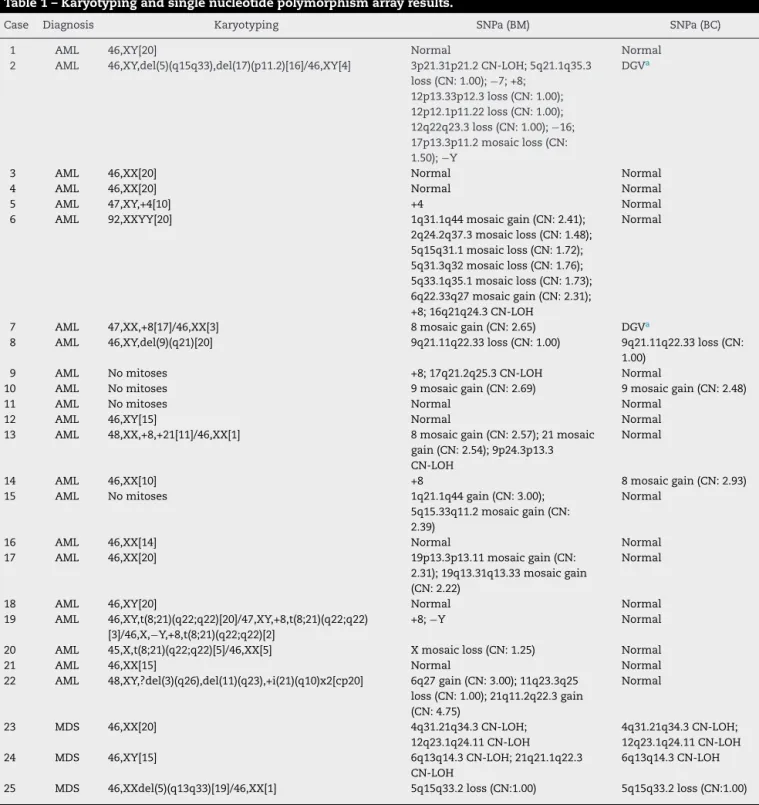

KaryotypingandSNParesultsarelistedinTable1.

Karyotype

Ten patients had abnormal karyotypes (40.0%), 11 normal (44.0%)andfourhadnomitosis(16.0%)(Figure2).

Karyotyping detected a total of 17 alterations (8 dele-tions/losses,7trisomies/gainsand2translocations)inthe25 cases(Figure3).

Singlenucleotidepolymorphismarray

ByBMSNPaanalysis,17patientswereabnormal(68.0%)and eightnormal(32.0%)(Figure2)andbyBCSNPaanalysis,six patientswereabnormal(24.0%),17werenormal(68.0%)and two had no results (8.0%). The internal quality control of Genechipfailedfortwosamples.

SNPaanalysisdetectedatotalof42alterations(17losses, 16gainsand9CN-LOH)inthe25cases(Figure3).

TheSNPamethoddetectedallabnormalitiesfoundby kar-yotypeexceptfor:

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

70%

Karyotype SNP array

No results

Normal

Abnormal 16%

32%

68% 44%

40%

Figure2–Resultsofkaryotyping(abnormal:10patients, normal:11patientsandnoresults:4patients)andbone marrowsinglenucleotidepolymorphismarrayanalysis (SNPa;abnormal:17patientsandnormal:8patients).

Karyotype 4 (8.7%)

Karyotype and SNPa 13 (28.3%)

SNPa 29 (63.0%)

Figure3–Frequencyofabnormalitiesdetectedby karyotypingonly:4(8.7%),bybonemarrowsingle nucleotidepolymorphismarray(SNPa)analysisonly:29 (63.0%)andbybothmethodssimultaneously:13(28.3%).

• polyploidyinCase6; • t(8;21)inCases19and20; • ?del(3)(q26)inCase22.

Ontheotherhand,SNPadetectedmanyabnormalitiesnot foundbykaryotyping:

• CN-LOH in 3p21.31p21.2, −7, +8, loss in 12p13.33p12.3,

12p12.1p11.22,12q22q23.3,−16and−YinCase1;

• mosaicgainin1q31.1q44 and6q22.33q27,+8mosaicloss

in2q24.2q37.3,5q15.q31.1,5q31.3q32,5q33.1q35.1and CN-LOHin16q21q24.3inCase6;

• CN-LOHin9p24.3p13.3inCase13(Figure4A); • +8inCase14;

• mosaicgainin19p13.3p13.11and19q13.31q13.33inCase17; • gainin6q27inCase22;

• CN-LOHin4q31.21q34.3and12q23.1q24.11inCase23; • CN-LOHin6q13q14.3and21q21.1q22.3inCase24.

Table1–Karyotypingandsinglenucleotidepolymorphismarrayresults.

Case Diagnosis Karyotyping SNPa(BM) SNPa(BC)

1 AML 46,XY[20] Normal Normal

2 AML 46,XY,del(5)(q15q33),del(17)(p11.2)[16]/46,XY[4] 3p21.31p21.2CN-LOH;5q21.1q35.3 loss(CN:1.00);−7;+8;

12p13.33p12.3loss(CN:1.00); 12p12.1p11.22loss(CN:1.00); 12q22q23.3loss(CN:1.00);−16; 17p13.3p11.2mosaicloss(CN: 1.50);−Y

DGVa

3 AML 46,XX[20] Normal Normal

4 AML 46,XX[20] Normal Normal

5 AML 47,XY,+4[10] +4 Normal

6 AML 92,XXYY[20] 1q31.1q44mosaicgain(CN:2.41);

2q24.2q37.3mosaicloss(CN:1.48); 5q15q31.1mosaicloss(CN:1.72); 5q31.3q32mosaicloss(CN:1.76); 5q33.1q35.1mosaicloss(CN:1.73); 6q22.33q27mosaicgain(CN:2.31); +8;16q21q24.3CN-LOH

Normal

7 AML 47,XX,+8[17]/46,XX[3] 8mosaicgain(CN:2.65) DGVa

8 AML 46,XY,del(9)(q21)[20] 9q21.11q22.33loss(CN:1.00) 9q21.11q22.33loss(CN:

1.00)

9 AML Nomitoses +8;17q21.2q25.3CN-LOH Normal

10 AML Nomitoses 9mosaicgain(CN:2.69) 9mosaicgain(CN:2.48)

11 AML Nomitoses Normal Normal

12 AML 46,XY[15] Normal Normal

13 AML 48,XX,+8,+21[11]/46,XX[1] 8mosaicgain(CN:2.57);21mosaic

gain(CN:2.54);9p24.3p13.3 CN-LOH

Normal

14 AML 46,XX[10] +8 8mosaicgain(CN:2.93)

15 AML Nomitoses 1q21.1q44gain(CN:3.00);

5q15.33q11.2mosaicgain(CN: 2.39)

Normal

16 AML 46,XX[14] Normal Normal

17 AML 46,XX[20] 19p13.3p13.11mosaicgain(CN:

2.31);19q13.31q13.33mosaicgain (CN:2.22)

Normal

18 AML 46,XY[20] Normal Normal

19 AML 46,XY,t(8;21)(q22;q22)[20]/47,XY,+8,t(8;21)(q22;q22) [3]/46,X,−Y,+8,t(8;21)(q22;q22)[2]

+8;−Y Normal

20 AML 45,X,t(8;21)(q22;q22)[5]/46,XX[5] Xmosaicloss(CN:1.25) Normal

21 AML 46,XX[15] Normal Normal

22 AML 48,XY,?del(3)(q26),del(11)(q23),+i(21)(q10)x2[cp20] 6q27gain(CN:3.00);11q23.3q25 loss(CN:1.00);21q11.2q22.3gain (CN:4.75)

Normal

23 MDS 46,XX[20] 4q31.21q34.3CN-LOH;

12q23.1q24.11CN-LOH

4q31.21q34.3CN-LOH; 12q23.1q24.11CN-LOH

24 MDS 46,XY[15] 6q13q14.3CN-LOH;21q21.1q22.3

CN-LOH

6q13q14.3CN-LOH

25 MDS 46,XXdel(5)(q13q33)[19]/46,XX[1] 5q15q33.2loss(CN:1.00) 5q15q33.2loss(CN:1.00)

SNPa:singlenucleotidepolymorphismarray;BM:bonemarrow;BC:buccalcells;AML:acutemyeloidleukemia;MDS:myelodysplasticsyndrome; CN:copynumber;LOH:lossofheterozygosity;DGV:genomicvariantsdatabase.

Loss:CN<2.00;gain:CN>2.00;normal:CN=2.00.YandXformale:normal:CN=1.00.

Figure4–Affymetrix®ChromosomeAnalysisSuiteImage.(A)Pairedanalysis(Buccalcellandbonemarrowsingle nucleotidepolymorphismarrayanalysis)ofchromosome9showingcopy-neutrallossofheterozygosity(CN-LOH)onlyin bonemarrow.(B)Pairedanalysis(Buccalcellandbonemarrowsinglenucleotidepolymorphismarrayanalysis)of chromosome1showing1q21.1q44gainonlyinbonemarrow.

• +8andCN-LOHin17q21.2q25.3inCase9; • mosaicgaininallchromosome9inCase10;

• gainin1q21.1q44,mosaicgainin5q15.33q11.2inCase15

(Figure4B).

Discussion

Cytogeneticabnormalities identifiedbykaryotypingremain themostimportantprognosticfactorinAML.2,24

Molecular karyotyping of these cases by SNPa analysis demonstratedadditionalinformationregardingmicroscopic, submicroscopic,andCN-LOHalterations;thecombinationof SNPaanalysiswithkaryotypingimprovesthedetectionrate forabnormalities.23

Clearly,theSNPamethoddoesnotreplacekaryotypingas itcannotdetectbalancedtranslocationsthatarerelevantto thediagnosisandmanagementofavarietyofhematopoietic malignancies.11

thesmallnumberofMDSpatientsincludedinthisstudy(three cases),allhadabnormalitiesdetectedbySNPaanalysis,while onlyonehadanabnormalkaryotype.

CN-LOHregionswerefoundinCases6,9,13,23and24(20% ofcases).Thisabnormalityrepresentsanimportant mech-anism by which point mutations and other micro lesions can be established in an homozygous state detectable by SNPaanalysis.13,25CN-LOHisthoughttobepositivelyselected

during clonal evolution because it can result in homozy-gosity for a mutationin one allele ofa tumor suppressor gene or oncogene, together with the loss ofthe wild-type allele.13,26

ConstitutionalSNPaanalysis(BC)wasdoneinallcasesin ordertoavoidfalsediscoveriesbycomparingwiththefindings for BM (Figure 4).13,18 In Case 23 two regions of

constitu-tionalCN-LOHwerefoundin4q31.21q34.3and12q23.1q24.11. InCase24 oneregionofconstitutionalCN-LOHwas found in 6q13q14.3. Therefore, the interpretation of these cases is that the abnormalities were not acquired, but constitu-tional.

Infourcases,thesamealterationwasfoundbothbyBM andBCSNPaanalysis(constitutional).Thealterationsfound byBCSNPaanalysisinCases10(mosaicgaininchromosome9) and14(mosaicgaininchromosome8)werepresentatalower levelthanbytheBMSNPaanalysis,thussuggestingthatthe BCmighthavebeencontaminatedwithbloodatthetimeof collection,thoughthesechangesmighthavebeendilutedin BC.13

InCases8(lossin9q21.11q22.33)and25(lossin5q15q33.2), thealterationsfoundintheBCSNPaanalysiswereseenby karyotypingandinterpretedasanacquiredalterationbecause inCase8thisdeletionwouldresultinconstitutional dimor-phismorrelatedsyndrome,whileinCase25theclonewas detectedbykaryotypingalongwithnormalcells.Supporting thisinterpretation,beyondthe scope ofthis work,we per-formedSNPaanalysisinCase8afterinductiontherapyand theproportionofthechange(CNV)waslower,thereby sug-gestingthatthisabnormalitywasaffectedbychemotherapy. Withthisevidence,weconsiderthesetwoabnormalitiesas acquired.

Thequalitycontrolmetricsintheconstitutional(BC)SNPa analysisfailedinCases2and7andinthesecasesweusedthe GenomicVariantsDatabasetovalidatethefindingsoftheBM SNPaanalysis.27Possibly,thefailurewasduetopoorquality

DNAfromBC.

InCases2and14,afterSNPaanalysis,somechromosomal abnormalities(−7,+8,−16and −Y)were foundinsporadic

metaphasesduringthekaryotypingreanalysis,buthad not initiallybeendescribedbecausetheydidnotmeetthe crite-riontobeconsideredasacytogeneticclone,15 thatis,more

thanthreecellswiththesamenumericalchangeortwocells withthesamerearrangement.28

Theapplicationofthe SNPa techniquehasbeen largely limitedtoexploratoryresearchoncancergenetics.However, givenitsexcellent performanceindetectinggenetic abnor-malitiesincancer,itsapplicationinclinicalonco-hematology couldbe alogicalsteptoattempt toestablish better man-agementofcancerpatients.11,29 Theredundancyoftestsis

beneficialforcomprehensiveandindistinctcharacterization ofthedisease.

SNPa analysis may add value to karyotyping-non-informativeresultsandoccasionallyrevealcryptic abnormal-itiesnotrecognizedbykaryotyping.23However,SNPaanalysis

shouldbeviewedasacomplimentarytool.Some abnormali-tiesdetectedbySNPaanalysisandnotalwaysrecognizedby karyotypingarenotyetincludedinclassificationand progno-siscriteria.30

Notwithstandingtheprogressinthisarea,SNPatestshave notbeenstudiedtotheirfullpotentialandmanyquestions remaintobeanswered;forinstance:

• InwhichsituationcouldSNPabeperformedinperipheral

bloodsamplesandwouldthetestofferthesame informa-tionasformarrowsamples?

• DoabnormalitiesfoundonlybySNPaanalysispresentthe

sameprognosticvalueaskaryotyping?

• ShouldabnormalkaryotypesalsobeinvestigatedbySNPa

inordertoamplifythedetectionofaberrations?

• Shouldtreatmentoptionstargetingspecificchromosomal

abnormalities be investigated by SNPa analysis before introducingthedrug?

• WhichSNParesultswoulddriveatreatmentchange? • Whatadditionalcostsareacceptableinordertoobtain

bet-tertreatmentdefinition?

Conclusion

In summary,SNPa analysis was standardizedin AML/MDS andresultswerecomparedwiththeabnormalitiesdetected bykaryotyping.SNPaanalysisincreasedthedetectionrateof abnormalitiescomparedtokaryotypingandalsoidentifieda newsetofabnormalitiesthatshouldbefurtherinvestigated infuturestudies.

Conflict

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgments

TheSNPatestwassupportedbyGrupoFleurywithincentive ofFinanciadoradeEstudoseProjetos(Finep).

MLChauffaillereceivedaCNPQ-ProdutividadeemPesquisa grant307747/2012-3andFAPESP-AuxílioPesquisa11/51751-0 that,inpart,supportedthisstudy.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1.MeyerSC,LevineRL.Translationalimplicationsofsomatic genomicsinacutemyeloidleukaemia.LancetOncol. 2014;15(9):e382–94.

2.CostaAR,VasudevanA,KrepischiA,RosenbergC,Chauffaille ML.Single-nucleotidepolymorphism-arrayimproves detectionrateofgenomicalterationsincore-bindingfactor leukemia.MedOncol.2013;30(2):579.

3.AdèsL,ItzyksonR,FenauxP.Myelodysplasticsyndromes. Lancet.2014;383(9936):2239–52.

myeloidleukemiainadults:recommendationsfroman internationalexpertpanel,onbehalfoftheEuropean LeukemiaNet.Blood.2010;115(3):453–74.

5. TiuRV,VisconteV,TrainaF,SchwandtA,MaciejewskiJP. UpdatesincytogeneticsandmolecularmarkersinMDS.Curr HematolMaligRep.2011;6(2):126–35.

6. WelchJS,LeyTJ,LinkDC,MillerCA,LarsonDE,KoboldtDC, etal.Theoriginandevolutionofmutationsinacutemyeloid leukemia.Cell.2012;150(2):264–78.

7. RaghavanM,LillingtonD,SkoulakisS,DebernardiS,Chaplin T,FootNJ,etal.Genome-widesinglenucleotide

polymorphismanalysisrevealsfrequentpartialuniparental disomyduetosomaticrecombinationinacutemyeloid leukemias.CancerRes.2005;65(2):375–8.Availablefrom:

http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/65/2/375.short

8. FrohlingS.Comparisonofcytogeneticandmolecular cytogeneticdetectionofchromosomeabnormalitiesin240 consecutiveadultpatientswithacutemyeloidleukemia.J ClinOncol.2002;20(10):2480–5.

9. SimonsA,Sikkema-RaddatzB,deLeeuwN,KonradNC, HastingsRJ,SchoumansJ.Genome-widearraysinroutine diagnosticsofhematologicalmalignancies.HumMutat. 2012;33(6):941–8.

10.SpeicherM,CarterN.Thenewcytogenetics:blurringthe boundarieswithmolecularbiology.NatRevGenet. 2005;6(10):782–92.

11.Sato-OtsuboA,SanadaM,OgawaS.Single-nucleotide polymorphismarraykaryotypinginclinicalpractice:where, when,andhow?SeminOncol.2012;39(1):13–25.

12.SchwartzS.Clinicalutilityofsinglenucleotidepolymorphism arrays.ClinLabMed.2011;31(4):581–94,viii.

13.HeinrichsS,LiC,LookAT.SNParrayanalysisinhematologic malignancies:avoidingfalsediscoveries.Blood.

2010;115(21):4157–61.

14.deLeeuwN,Hehir-KwaJY,SimonsA,GeurtsvanKesselA, SmeetsDF,FaasBH,etal.SNParrayanalysisinconstitutional andcancergenomediagnostics–copynumbervariants, genotypingandqualitycontrol.CytogenetGenomeRes. 2011:212–21.

15.SimonsA,ShafferLG,HastingsRJ.CytogeneticNomenclature: ChangesintheISCN2013Comparedtothe2009Edition. CytogenetGenomeRes.2013[Epubaheadofprint].

16.YiJH,HuhJ,KimHJ,KimSH,KimSH,KimKH,etal. Genome-widesingle-nucleotidepolymorphismarray-based karyotypinginmyelodysplasticsyndromeandchronic myelomonocyticleukemiaanditsimpactontreatment outcomesfollowingdecitabinetreatment.AnnHematol. 2013;45:9–69.

17.PinheiroR,ChauffailleM.ComparisonofI-FISHand G-bandingforthedetectionofchromosomalabnormalities duringtheevolutionofmyelodysplasticsyndrome.BrazJMed BiolRes.2009;42(11):425.

18.ParkinB,OuilletteP,LiY,KellerJ,LamC,RoulstonD,etal. Clonalevolutionanddevolutionafterchemotherapyinadult acutemyelogenousleukemia.Blood.2013;121(2):369–77.

19.YamamotoG,NannyaY,KatoM,SanadaM,LevineRL, KawamataN,etal.Highlysensitivemethodforgenomewide detectionofalleliccompositioninnonpaired,primarytumor specimensbyuseofaffymetrix

single-nucleotide-polymorphismgenotypingmicroarrays. AmJHumGenet.2007;81(1):114–26.

20.HugginsR,LiLH,LinYC,YuAL,YangHC.Nonparametric estimationofLOHusingAffymetrixSNPgenotypingarrays forunpairedsamples.JHumGenet.2008;53(11-12): 983–90.

21.CooleyLD,LeboM,LiMM,SlovakML,WolffDJ,Working GroupoftheAmericanCollegeofMedicalGeneticsand Genomics(ACMG)LaboratoryQualityAssuranceCommittee. AmericanCollegeofMedicalGeneticsandGenomics technicalstandardsandguidelines:microarrayanalysisfor chromosomeabnormalitiesinneoplasticdisorders.Genet Med.2013;15(6):484–94.

22.GibsonSE,LuoJ,SathanooriM,LiaoJ,SurtiU,SwerdlowSH. Whole-genomesinglenucleotidepolymorphismarray analysisiscomplementarytoclassicalcytogeneticanalysisin theevaluationoflymphoidproliferations.AmJClinPathol. 2014;141(2):247–55.

23.TiuRV,GondekLP,O’KeefeCL,HuhJ,SekeresMA,ElsonP, etal.Newlesionsdetectedbysinglenucleotide

polymorphismarray-basedchromosomalanalysishave importantclinicalimpactinacutemyeloidleukemia.JClin Oncol.2009;27(31):5219–26.

24.CostaAR,BelangeroSI,MelaragnoMI,ChauffailleML. Additionalchromosomalabnormalitiesdetectedbyarray comparativegenomichybridizationinAML.MedOncol. 2012;29(3):2083–7.

25.XuX,JohnsonEB,LevertonL,ArthurA,WatsonQ,ChangFL, etal.TheadvantageofusingSNParrayinclinicaltestingfor hematologicalmalignanciesdacomparativestudyofthree genetictestingmethods.CancerGenet.2013;206(9–10): 317–26.

26.RadtkeI,MullighanCG,IshiiM,SuaX,ChengaJ,MabJ,etal. Genomicanalysisrevealsfewgeneticalterationsinpediatric acutemyeloidleukemia.ProcNatlAcadSciUSA.

2009;106(31).Availablefrom:

http://www.pnas.org/content/106/31/12944.short

27.MilosevicJD,PudaA,MalcovatiL,BergT,HofbauerM, StukalovA,etal.Clinicalsignificanceofgeneticaberrations insecondaryacutemyeloidleukemia.AmJHematol. 2012;87(11):1010–6.

28.ChauffailleML.Alterac¸õescromossômicasemsíndrome mielodisplásica.RevBrasHematolHemoter.2006;28(3):182–7.

29.YiJH,HuhJ,KimHJ,KimSH,KimHJ,KimYK,etal.Adverse prognosticimpactofabnormallesionsdetectedby genome-widesinglenucleotidepolymorphismarray-based karyotypinganalysisinacutemyeloidleukemiawithnormal karyotype.JClinOncol.2011;29(35):4702–8.

30.ChauffailleML.AddingFISHtokaryotypeinmyelodysplastic syndromeinvestigationdiagnosis:areallquestions