w w w . r b o . o r g . b r

Update

article

Stress

fractures:

definition,

diagnosis

and

treatment

夽

Diego

Costa

Astur

∗,

Fernando

Zanatta,

Gustavo

Gonc¸alves

Arliani,

Eduardo

Ramalho

Moraes,

Alberto

de

Castro

Pochini,

Benno

Ejnisman

UniversidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received5January2015 Accepted5February2015

Availableonline30December2015

Keywords:

Stressfracture/epidemiology Stressfracture/physiopathology Stressfracture/diagnosis Stressfracture/classification Stressfracture/treatment

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

StressfractureswerefirstdescribedinPrussiansoldiersbyBreithauptin1855.Theyoccur astheresultofrepeatedlymakingthesamemovementinaspecificregion,whichcanlead tofatigueandimbalancebetweenosteoblastandosteoclastactivity,thusfavoringbone breakage.Inaddition,whenaparticularregionofthebodyisusedinthewrongway,a stressfracturecanoccurevenwithouttheoccurrenceofanexcessivenumberoffunctional cycles.Theobjectiveofthisstudywastoreviewthemostrelevantliteratureofrecentyears inordertoaddkeyinformationregardingthispathologicalcondition,asanupdatingarticle onthistopic.

©2015SociedadeBrasileiradeOrtopediaeTraumatologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditora Ltda.Allrightsreserved.

Fraturas

por

estresse:

definic¸ão,

diagnóstico

e

tratamento

Palavraschave:

Fraturasporestresse/epidemiologia Fraturasporestresse/fisiopatologia Fraturasporestresse/diagnóstico Fraturasporestresse/classificac¸ão Fraturasporestresse/tratamento

r

e

s

u

m

o

AfraturaporestressefoidescritainicialmenteemsoldadosprussianosporBreithauptem 1855eocorrecomooresultadodeumnúmerorepetitivodemovimentosemdeterminada regiãoquepodelevarafadigaedesbalanc¸odaatuac¸ãodososteoblastoseosteoclastose favorecerarupturaóssea.Alémdisso,quandousamosumadeterminadaregiãodocorpo demaneiraerrônea,afraturaporestressepodeocorrermesmosemqueocorraumnúmero excessivodeciclosfuncionais.Oobjetivodesteestudoérevisaraliteraturamaisrelevante dosúltimosanosparaagregarasprincipaisinformac¸õesarespeitodessapatologiaemum artigodeatualizac¸ãodotema.

©2015SociedadeBrasileiradeOrtopediaeTraumatologia.PublicadoporElsevierEditora Ltda.Todososdireitosreservados.

夽

WorkperformedattheSportsTraumatologyCenter,EscolaPaulistadeMedicina,UniversidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo,SãoPaulo,SP, Brazil.

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:mcastur@yahoo.com(D.C.Astur). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rboe.2015.12.008

Introduction

Stressfractures werefirst described inPrussian soldiersby Breithauptin1855.1–3Theywerenamed“marchfractures”and

theircharacteristicswereconfirmed40 yearslaterwiththe adventofradiography.1,2In1958,Devasmadethefirstreport

onstressfracturesinathletes.1–3

Thisinjuryoccurs asaresultofhighnumbersof occur-rences of cyclical overloading of intensity lower than the maximumbonestrength,onnon-pathologicalbonetissue.4–6

Thesefracturesmaybethefinalstageoffatigueor insuf-ficiencyofthe boneaffected.6 Fatiguefractures occur after

formationandaccumulationofmicrofracturesinnormalbone trabeculae.Ontheotherhand,fracturesresultingfrombone insufficiencyoccurinbonethatismechanicallycompromised and generally presents low bonemineral density.6 In both

situations,imbalancebetweenthebonethatisformedand remodeledandthebonethatitreabsorbedwillresultin dis-continuityofthe boneatthe siteaffected.7,8 Theaimhere

wastopresentanupdatingarticleonthistopicandcondense themaininformationobtainedthroughthemostimportant studiespublishedoverthelastfewyears.

Epidemiology

Population

Runners,soldiersanddancersarethemainvictimsofstress fractures.6,9,10

Anatomicalregion

All the bonesofthe humanbody are subject tofracturing causedby stress.Thisstress isclosely related tothe daily practicethatathletesundertake.Thepredominanceofstress fracturesinthelowerlimbs,overfracturesintheupperlimbs, reflectsthecyclical overloadingthatistypicallyexertedon bonesthatbearthebodyweight,incomparisonwithbones thatdonothavethisfunction.3Stress fracturesaremostly

commonlydiagnosedinthetibia,followedbythemetatarsals (especially the second and third metatarsals) and by the fibula.3,11Stressfracturesintheaxialskeletonareinfrequent

andaremainlylocatedintheribs,parsinterarticularis,lumbar vertebraeandpelvis.11–13

Typesofsport

Runnerspresentgreatestincidenceofstressfracturesinlong bonessuchasthetibia, femurand fibula,andalsopresent fracturesinthebonesofthe feetandsacrum.11,12 Typesof

sport inwhichthe upperlimbsare used, suchasOlympic gymnastics,14 tennis,baseball andbasketballmay resultin

fracturesduetostress.Thebonemostaffectedistheulna, especiallyinitsproximalportion,whilethedistalextremity ofthe humerusisalsoaffected.6,11,13Stress fracturesoccur

mainlyintheribsingolfersandrowers11,13Jumpers,bowlers

anddancerspresentgreatestriskofinjurytothelumbarspine andpelvis.11

Sex

Amongathletes,thedifferenceintheincidenceofstress frac-turesbetweenmenandwomenisminimal.Itisbelievedthat theintensityandtypeofcontrolledtrainingforeachathlete andthephysicalpreparationthatalreadyexistsdiminishthe impactofthetrainingprogram.9,15Inthemilitarypopulation,

theincidenceofstressfracturesamongfemalesisgreaterthan amongmen.16,17

Physiopathology

Sixtoeightweeksafterasuddenandnon-gradualincrease intheintensityofanathlete’sornewpatient’sphysical activ-ity,thiscyclicalandrepetitivephysiologicaloverloadingmay leadtotheappearanceofmicrofracturesandmaynotallow thebonetissuetohavesufficienttimetoundergo remodel-ing andadapt tothe newcondition, andthustorepairthe microlesion.4–6,10,18,19 Theload appliedis considered to be

insufficienttocauseanacutefracture,butthecombinationof overloading,repetitivemovementsandinadequaterecovery timemakethisachronicinjury.11Elasticdeformationoccurs

initially,andthisprogressestoplasticdeformityuntilitfinally resultsinmicrofracturing.Ifthisisnottreated,itwillevolve tocompletefracturingoftheboneaffected.10Thebonerepair

processinstressfracturesdiffersfromtheprocessincasesof commonacutefracturesandonlytakesplacethroughbone remodeling,i.e.reabsorptionoftheinjuredcellsand replace-mentwithnewbonetissuetakeplace.19

Markeyalsoproposedthatthemusclemassactstoward dispersing and sharing impactloads on the bonetissue.20

Therefore,whenfatigue,weaknessormuscleunpreparedness occur,thisprotectiveactionislostandtheriskofbonetissue lesionsincreases.16,20

Risk

factors

The factors associatedwith increasedrisk ofdevelopment ofstress fracturescan bedividedinto extrinsicand intrin-sic factors. This makes stress fractures multifactorial and difficult to control.8,9,20–23Extrinsic factors relate to sports

movements,nutritionalhabits,equipmentusedandthetype ofground.8,9,14,20–23

Abruptincreasesintheintensityandvolumeoftraining areoftenenoughforlesionstodevelop.6,9–11Equipmentsuch

asfootwearthathaslowimpactabsorption,iswornout(more thansixmonthsofuse)orisabadfitfortheathlete’sfootmay causeinjuries.8,23 Thequalityofthetrainingtrackmayalso

beariskfactor,whenitisuneven,irregularorveryrigid.17,24

Lastly,iftheathlete’sfitnesslevelisinsufficientforthesports movement orfunctionaltechnique,thismayleadtoinjury, sometimes withoutthe number ofrepetitions having been veryhigh.8,25

Theintrinsicfactors relatetopossibleanatomical varia-tions,muscleconditions,hormonalstates,gender,ethnicity orage.8,9,20–22

reality,hormonal,nutritional,biomechanicalandanatomical alterationsarethetruefactorsthatfavorappearanceofstress fracturesinwomen.11,24

Agealsocannotbeconsideredtobeariskfactorin isola-tionforstressfractures.11,23,27StudiesconductedintheUnited

States have attempted to evaluate the incidence of these injuriesamongwhite andblackathletes,withoutobserving anysignificantdifferences.11,13 Inamilitarypopulation,the

incidenceamongwhiteswastwiceashighasamongblacks, withoutanydifferencebetweenthesexes.Thiswasattributed tobonedensityanditsbiomechanics.24

There is an inverse relationship between bone mineral densityandtheriskofstressfractures.8,10,28Inadequate

nutri-tional intake may alter bone metabolism and predispose towardappearanceofstressfractures.8,10,29

Lowlevelsofphysicalandmuscleconditioningarealsoan importantriskfactorforthegenesisofthisproblem.6,8,10,30,31

Furthermore,rigidpescavus,discrepancyofthelowerlimbs, shorttibia,genuvalgum,increasedQangle,bodymassindex lowerthan21kg/m2 andshortstature shouldalsobetaken

into consideration in analyzing the risk factors for stress fractures.6,8,9,21,32

Somestudieshavealsosuggestedthatstiffnessofthefeet, alterationstotheplantararchandlimitationsofdorsiflexion duetoshorteningofthesuraltricepsmayberiskfactors.8,10,33

Runnerswhosehindfootpresentseversion,particularlywith excessive pronation, and athletes witha pronounced high archhaveariskofdevelopingstressfracturesthatisup to 40%higher.10,21,33,34Moreover,hyperpronationoftheforefoot

predisposestowardincreasedriskofstressfracturesinthe fibula.35Stressfracturesinthesecondmetatarsalhavebeen

correlatedwithpresenceofMorton’sneuroma, hypermobil-ityofthefirstmetatarsalandarelativeincreaseinthelength ofthesecondmetatarsal.20,33Althoughuseoforthosesand

footwearthatismoreappropriatetheoreticallydecreasesthe incidenceofstress fractures,the number ofstudies inthe literatureremainsinsufficienttosustainthistheory.10,34

Otherauthorshavealsoconsideredthatthefollowingare riskfactors:smoking,physicalactivityoffrequencylessthan threetimesaweekandconsumptionofmorethan10doses ofalcoholicdrinkperweek.6

Physical

examination

Physicalexaminationofstressfracturesisverysensitivebut unspecific.20,36Patientspresentincreasedsensitivity,painand

edemaatthelesionlocationafteranabruptand/orrepetitive increaseinphysicalactivitywithinsufficientrestintervalsfor physiologicaltissuerecovery.6Initially,thepainisreducedand

alleviatedthroughrestandthisallowsunimpairedphysical activity.However,iftheaggressivemovementismaintained, the injury will progress, thus resulting in increased pain andlimitationofpracticingthis movement.9,20 Information

regardinganypreviousfractures,weight,height,bodymass indexand its changes over the last 12 months, menstrual andpubertyhistoryandnutritionalevaluationsisimportant foridentifyingpossibleintrinsicriskfactorsforinjuryduring physicalexaminations.10

Clinical testssuchasuse oftherapeuticultrasound and tuningforksare alsouseful indiagnosticinvestigations on stressfractures.3Whenuseddirectlyonthesiteofthe

sus-pectedlesion,theymaytriggerorworsenthepainbecause of the great local osteoclastic reabsorption, which results in injury to the periosteum.3,37 In addition, the skipping

rope test (hop test) can be used: this consists of asking the patient to hop on the spot while putting weight on the limb that is under investigation. The test is positive whenit triggersstrong orincapacitatingpainintheregion injured.6,38

Somelaboratorytestsmaybeusefulininvestigatingstress fractures:serumlevelsofcalcium,phosphorus,creatinineand 25(OH)D3. Nutritional markers should be requested in the presenceofclinicalconditionsofweightlossandanorexia. Hormonal levels(FSHand estradiol)shouldbeinvestigated whenthereisahistoryofdysmenorrhea.10

Imaging

examinations

Imagingexaminationsarefundamentalfordiagnosing, prog-nosingandfollowingupstressfractures.6

Simpleradiography (X-ray) isthe initialimaging exami-nationbecauseofitseaseofaccessandlowcost.4,13,36,38–42

However, it has a high false-negative rate, given that the alterations caused bystress fractures onlyappearon such examinationsatalatestage(twotofourweeksafterthestart ofthepain),whichmaydelaythediagnosis.6,14,18,43Initially,a

subtleweakradiolucentareacanbeobserveddirectlyonthe bonetissueaffected and/orsclerosis,periostealthickening, corticalchangescomprisingdiminishedcorticalbonedensity (gray cortex) and/or appearance ofa delicate fracture line. Finally, an attempt bythe organism toform abone callus isobserved,withendostealthickeningandsclerosis,which arethecommonestfindings.6,10,14,38,44Thesignknownasthe

dreadedblacklineoccursintheanteriorcorticalboneofthe tibiaandsuggeststhepresenceofafracturewithapoor prog-nosisandahighprobabilityofevolutiontoacompletefracture becauseofitslocationinaregionofbonetensionandpoor vasclarization.44

Computed tomography (CT)is used mainly when there is a contraindication against using magnetic resonance imaging.43–46 Chronic and quiescent lesions may be more

evident in this examination than on magnetic resonance imagingorbonescintigraphybecausetheypresentlowbone turnover.46SinglephotonemissionCT(SPECT)hasbeen

par-ticularlymoreusefulininvestigatingstressfracturesinvolving the dorsal spine, and specifically in pars interarticularis (spondylolysis).6,45,46

Nuclear medicine using triple-phase scintigraphy (technetium-99m)presents significant sensitivity(74–100%) toboneremodelingandshowsimagingalterationsthreeto fivedaysafterthestartofsymptoms.3,6,41,42,47The

radiophar-maceutical becomes concentrated in the regions affected anddetectsareasofboneremodeling,microfracturesofthe trabecular bone,periosteal reactionand formation ofbone callus.46

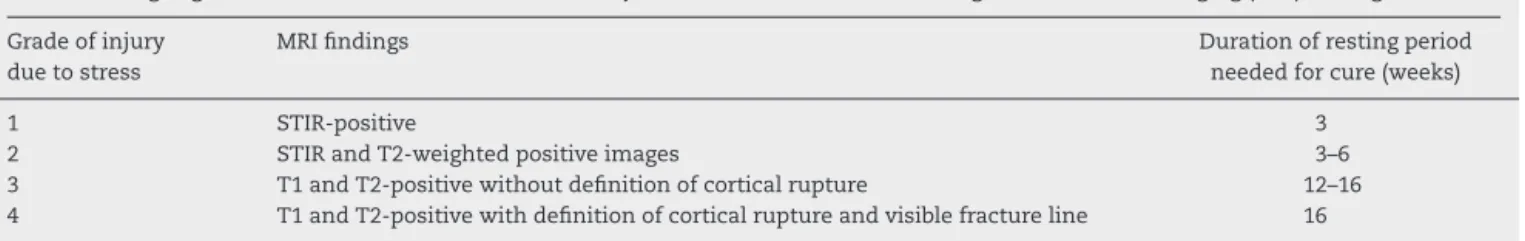

Table1–ClassificationofArendtandGriffiths.

Stages/gradesofArendtandGriffithsforboneinjuriesduetostress,basedonmagneticresonanceimaging(MRI)findings

Gradeofinjury duetostress

MRIfindings Durationofrestingperiod

neededforcure(weeks)

1 STIR-positive 3

2 STIRandT2-weightedpositiveimages 3–6

3 T1andT2-positivewithoutdefinitionofcorticalrupture 12–16

4 T1andT2-positivewithdefinitionofcorticalruptureandvisiblefractureline 16

fractures. It is recommended by the American College of Radiology as the preferred examination in the absence of radiographic alterations.6 The abnormalities caused bythe

fracturecanbeidentifiedonetotwodaysafterthestartof thesymptoms,6,10,12,38,41,43,46,48withearlydetectionofedema

in the bone tissue and adjacent areas.10,41,46 This

exami-nationmakesitpossibletodifferentiatemedullarydamage from cortical,endosteal and periostealdamageallows gra-dationofthelesionsregardingtheirseverityandprognosis.6

Intramedullaryendosteal edemaisoneofthefirstsigns of boneremodelingandmaycontinuetobepresent forup to sixmonthsafterthefracturehasbeendiagnosedandtreated, whilethecorticalmaturationandremodelingtakeplace.16,48

Medullaryedemaorsignsofbonestressmayalsobepresentin asymptomaticphysicallyactivepatients,withoutany correla-tionwithincreasedincidenceofstressfractures,especiallyin thetibiainmarathonrunners.46Thefracturelineisless

com-monlyvisible.10Itpresentssensitivityslightlygreaterthanor

equaltothatofscintigraphy,butitisconsideredtobeamore specificexamination.6,38,41

Classification

Fracturescanandshouldbeclassifiedsothattheprognosis andtreatmentcanbemeasuredandthusgiverisetoabetter resultforthepatient.

Arendt and Griffiths apud Royer et al.11 used imaging

parametersobtainedthroughMRItodividestressfractures intofourstages.Theaimofthisclassificationistodefinethe lengthofrestingtimethat isneededforareturn tosport, according to the patient’s current stage. These stages can alsobeusedforreevaluationduringfollow-upofthelesion.7

Lesionstreatedatstage1requireanaverageof3.3weeksof resting,whilethoseatstage4require14.3weeks7(Table1).

Table2–Classificationoflow-riskstressfractures.

Low-riskstressfractures

Upperlimbs Clavicle,scapula,humerus,olecranon,ulna, radius,scaphoid,metacarpals

Lowerlimbs Femoraldiaphysis,tibialdiaphysis,fibula, calcaneus,metatarsaldiaphyses

Thorax Ribs

Dorsalspine Parsinterarticularis,sacrum Pelvis Ischiopubicrami

Table3–Classificationofhigh-riskstressfractures.

High-riskstressfractures Femoralneck(superolateral) Anteriorcorticalboneofthetibia Medialmalleolus

Navicularbone

Baseofthesecondmetatarsal Talus

Patella

Sesamoids(hallux) Fifthmetatarsal

Stressfracturescanalsobeclassifiedashighandlow-risk fractures. The bone location, the prognosis for consolida-tionandtraitsascertainedthroughimagingexaminationsare someofthecharacteristicsthatdefinewhetherthereishigher riskthatastressfracturemightnotevolvesatisfactorilyduring thetreatment6,11(Tables2and3).

Fredericson proposed a stress fracture classification throughusingthe alterationsseenonMRI.Theprogressive stagesoflesionseverityareassessedaccordingtoperiosteal involvement,followedbymedullaryinvolvementandgoing asfarasthepointatwhichthecorticalbonealsobecomes compromised10,41(Table4).

Treatment

Inordertoadequatelytreatstressfractures,itisessentialto identifyriskfactorsthatleadtodisease.Treatmentsforstress fractures are based on preventionofnewepisodes and on recoveryoftheinjuredarea.6,10,20

Table4–Fredericsonclassification.

MRIfindingsaccordingtoFredericson

Lesionstage

0 Normal

1 Periostealedema

2 PeriostealandmedullaryedemaonT2-weighted images

3 PeriostealandmedullaryedemaonT1and T2-weightedimages

Preventionofnewepisodesisachievedthrough modify-ingactivities,correctingsportsmovements,changingsports equipment,changingtraininglocationsthatmightbe favor-ingboneoverloading,changingnutritionalhabits,recognizing hormonal,anatomical andmuscle strength alterationsand recognizinglowcardiomuscularconditioning.20Theidealtype

of footwear for each type of sports practice is the exter-nal factor that has been studied most with regard to the genesisofstressfractures.20Somestudieshaveshownthat

thereislowerincidenceofinjurieswhenrunningonasphalt isreplacedbyrunning onsoftersurfaces,suchasathletics tracks.Nonetheless,otherauthorshavereportedintheir stud-iesthat therewasno relationshipbetweenthesefactors.20

Voloshin49believedthattherewasinterferencebetweenthe

differentshock-absorbingsurfaces:thestressonthebone tis-sueisnotduesolelytothereactionforcesfromtheground. Thecombinedforcesgeneratedbymuscleactionthroughthe athlete’smovementandhisadaptationtothetrainingsurface mayalsobeconsideredtoberiskfactorsforagiventypeof injury.20,49

Thetreatmentsfortheseinjuriescomprisediminutionof theoverloadingonthesiteaffected,medicationforpain con-trolandphysiotherapeuticrehabilitation.6,10,20

Analgesics are used for pain relief.6 Anti-inflammatory

drugs, if used, should be prescribed cautiously and only for short periods. Studies on animals have demonstrated thattheremaybenegativeinterferenceinthebonehealing process.6However,reviewsoftheliteratureconductedmore

recentlyhavereportedthatthereisnoconclusiveevidence regardingthisnegativeaction.50–52

The time taken for fracture consolidation is generally betweenfourand12weekswhenthefracturesarelow-risk.6

Forthemetatarsals,atimeofthreetosixweeksisexpected, whilefor the posteromedial region of the tibial diaphysis, the femurand the pelvis, sixto12 weeks isexpected.10,11

Thepatientshouldbereexaminedeverytwotothreeweeks, tomonitor the changesto the symptoms and pain during restingandrehabilitationperiods.6,53–56INordertomaintain

flexibility,strengthandcardiovascularphysicalconditioning duringthe restingperiod, thepatient needstobeengaged inaphysiotherapy program6,53,54 and acontrolled exercise

program.57

Immobilizationisonlyrarelyusedfortreatingstress frac-turesbecauseofitsdeleteriouseffectsonmuscles,tendons, ligamentsandjoints.5However,therearesomespecifictypes

of fracture for which immobilization is fundamental for obtainingappropriateconditionsforacure:thisisthecase forthenavicularbone,sesamoids,patellaandposteromedial regionofthetibia.5

High-riskfracturescommonlyevolvetonon-consolidation of the bone and surgical intervention by an orthopedist becomesnecessary.6 Stress fractures ofthe lateral cortical

bone(duetotension)atthefemoralneckisassociatedwith catastrophicresults,suchascomplete displacement ofthe femoral head and osteonecrosis, when this is not treated surgically.20,53 Fracturesoftheanterior corticalboneofthe

middle third ofthe tibialdiaphysis are another type that, ifnottreatedsurgically,mostlypresentsanextremelypoor prognosis.20Fracturesofthebaseofthefifthmetatarsaland

ofthenavicularbonecanalsobecitedastypesthatcommonly

requiresurgicalinterventioninordertoachieveasatisfactory resultfromtheirtreatment.20

New

types

of

therapy

Somenewtypesoftherapyforstressfracturesarebeing stud-ied with the aim ofachieving faster consolidation and an earlierreturntophysicalactivities.Thesecanbedividedinto biologicalandphysicalmethods.50

Oxygensupplementationtherapy(hyperbaricoxygen therapy)

In vitro studies have demonstrated that administration of 100%oxygeniscapableofstimulatingosteoblastsand conse-quentlyboneformation.50However,thereisstillnoconsensus

in the literature regarding its benefits for treating stress fractures.50,54

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonatessuppressbonereabsorptionandinactivate osteoclasts through their bonding withcalcium phosphate crystals.20,50Theirhighcostandvarioussideeffectsmaybe

thedecidingfactorwithregardtochoosingandattemptingto usethistherapeuticmethod.50,55Thereisnotyetanyscientific

basisfortheirprophylacticuse.50,56

Growthfactorsandgrowthfactor-richpreparations

Growth factorsareapplieddirectlytodiseasedtissueswith the aim of accelerating and promoting their repair. The preliminary results from muscles, tendons and ligaments have been encouraging.50,57 There are only a few studies

on treating stress fractures. Some of them have reported thatwhenthesefactorsare usedduringsurgicaltreatment ofhigh-riskfractures,theymayaccelerateand improvethe recovery.50

Bonemorphogenicproteins

Bonemorphogenicproteinscontainbioactivefactorsthatare responsibleforinducingbonematrixactivitywithan osteoin-ductive function.50 Their primary activity is in relation to

differentiationofmesenchymalcellsintoboneandcartilage tissue-formingcells,throughdirectandosteochondral ossi-fication.Theyhaveanimportantfunctioninrepairingbone lesions.Studiesonanimalshavedemonstratedacceleration of the injury cure process in cases of traumaticfractures, but little can be concluded regarding their use in stress fractures.50

Recombinantparathyroidhormone

Parathormone actstoward regulating serum calcium levels through gastrointestinal absorption, calcium and phospho-rusreabsorptioninthekidney,andcalciumreleasefromthe skeletal tissue.50 Although this initially promotes

isdone intermittentlyin acontrolledmanner, it givesrise toanabolic stimulationofosteoblastsandresultsin forma-tionofbonewithincreasedstrengthanddensity,followedby remodeling.50Studieshavedemonstratedthatthishormone

stimulatesbonerepairthroughbothendochondraland mem-branousmechanisms.50

Low-intensitypulsatileultrasonography

High-frequencysoundwavesthatareabovetheaudiblelimit of human beings interact with bone tissue and the adja-centsofttissuesand generatemicrostressandtensionthat arecapableofstimulatingconsolidation.6,13,50However,their

exactmechanismofactionremainsunknown.19Somestudies

havedemonstrateditsefficacyintreatingstressfractures.50,58

Otherstudieshavecompletelysupporteditsusefortreating thesefractures.6

Applicationofmagneticfields

Magneticfieldscanbeappliedbymeansofadirectcurrentat thefocusofthefracturethroughsurgicalplacementof elec-trodes,useofanelectricalcapacitationfielddeviceoruseof electromagneticfieldpulses.50Thereisstillnoconcrete

evi-denceregardingitsuseinstressfractures.20,50

Criteria

for

return

to

sport

Thetimetakenfromdiagnosis tocureand untilthereturn tosportdependsonmultiplefactorssuchastheinjurysite, sportsactivity, severityoftheinjury andpossibility of cor-rectingriskfactorsthatareintrinsictothepatient.20Low-risk

stressfracturesandnon-surgicaltreatmentusuallymakeit possibleforthepatienttoreturntohisactivitiesfourto17 weeksaftertheinjury.6

Thecriteriathat can beusedforallowing anathlete to returntohispracticemayinclude:totalabsenceofpainat thesiteaffected,especiallyduringsportsmovements;absence ofsymptomsduringpainprovocationtestsattheinjurysite; absenceofabnormalitiesinimagingexaminations;and,above all,comprehensionbythepatient,trainersandtechnicalteam ofthesportregardingtheriskfactorsandconditionsthatled totheinjury,sothatcorrectionscanbemadesoastoprevent recurrenceandreappearanceofinjuries.10

Thegradualdefinitivereturntosportsactivityshouldbe startedafterthepatienthasbeenfreefrompainfor10–14days, with10%increasesintrainingintensityperweek.20,50

Forma-tionofabonecallusandobliterationofthefracturelineon simpleradiographsand,especially,oncomputedtomography scansarethefactorsthatdeterminewhetherthecureprocess forthestressfracturehasbeenadequate.50

Prevention

Althoughseveralmethodsforpreventingstressfractureshave been proposed,onlysomeofthem presentproven validity thatcanjustifytheirrecommendations.6Thepossiblerisk

fac-torsthatcontributetoappearanceofthesefracturesneedto

becarefullystudied,modifiedandfollowedup.6,10 Constant

controlandmodificationofphysicalactivity,withadequate recovery time,are extremelyimportant.6,10 Itisconsidered

thatdailyintakeof2000mgofcalciumand800IUofvitamin D maybeprotectionfactors.6,9 Thekinematicsand

biome-chanicalfactorspredisposingtowardsuchfracturesneedto bemonitoredandcorrected,throughcorrectunderstanding ofthesportsmovements,equipment,orthoses,training sur-faceandalltheotherfactorsthatmaybeinvolvedinsports practice.6,10,50 Some studies have investigated prophylactic

use ofbisphosphonatesforpreventing stressfractures, but thereisstillnoevidenceregardingitsbenefitsinprevention ofthistypeofinjury.6

Complications

Themaincomplicationsoccurincasesofhigh-riskstress frac-tures.Inappropriatemanagementmaycauseprogressionof the fracture to acomplete and displaced fracture line and thus give rise to delayed consolidation, avascularnecrosis and pseudarthrosis.6,20 Furthermore,bisphosphonatesused

intreatingstressfractures mayweaken someboneregions when usedoverthe longterm and maypredisposetoward appearanceoffracturesduetoinsufficiencyandapotential teratogeniceffectamongpregnantpatients.6

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1.BreithauptMD.Zurpathologiedesmenschlichenfusses.To thepathologyofthehumanfoot.MedZeitung.1855;24:169. 2.DevasMB.Stressfracturesofthetibiainathletesof‘shin

soreness.JBoneJointSurgBr.1958;40(2):227–39. 3.SchneidersAG,SullivanSJ,HendrickPA,HonesBDGM,

McmasterAR,SugdenBA,etal.Theabilityofclinicalteststo diagnosestressfractures:asystematicreviewand

meta-analysis.JOrthopSportsPhysTher.2012;42(9):760–71. 4.FayadLM,KamelIR,KawamotoS,BluemkeDA,FrassicaFJ,

FishmanEK.Distinguishingstressfracturesfrompathologic fractures:amultimodalityapproach.SkeletRadiol. 2005;34(5):245–59.

5.NivaMH,MattilaVM,KiuruMJ,PihlajamäkiHK.Bonestress injuriesarecommoninfemalemilitarytrainees:a

preliminarystudy.ClinOrthopRelatRes.2009;467(11):2962–9. 6.CarmontRC,Mei-DanO,BennellLK.Stressfracture

management:currentclassificationandnewhealing modalities.OperTechSportsMed.2009;17:81–9. 7.PatelDS,RothM,KapilN.Stressfractures:diagnosis,

treatment,andprevention.AmFamPhysician. 2011;83(1):39–46.

8.EvansRK,AntczakAJ,LesterM,YanovichR,IsraeliE,Moran DS.Effectsofa4-monthrecruittrainingprogramonmarkers ofbonemetabolism.MedSciSportsExerc.2008;4011 Suppl.:S660–70.

10.BennellKL,MalcolmSA,ThomasSA,WarkJD,BruknerPD. Theincidenceanddistributionofstressfracturesin competitivetrackandfieldathletes.Atwelve-month prospectivestudy.AmJSportsMed.1996;24(2):211–7. 11.RoyerM,ThomasT,CesiniJ,LegrandE.Stressfracturesin

2011:practicalapproach.JointBoneSpine.2012;79Suppl. 2:S86–90.

12.SnyderRA,KoesterMC,DunnWR.Epidemiologyofstress fractures.ClinSportsMed.2006;25(1):37–52.

13.IwamotoJ,TakedaT.Stressfracturesinathletes:reviewof196 cases.JOrthopSci.2003;8(3):273–8.

14.DaffnerRH,PavlovH.Stressfractures:currentconcepts.AmJ Roentgenol.1992;159(2):245–52.

15.JohnsonAW,WeissCBJr,WheelerDL.Stressfracturesofthe femoralshaftinathletes–morecommonthanexpected:a newclinicaltest.AmJSportsMed.1994;22(2):248–56. 16.JonesBH,BoveeMW,HarrisJM,CowanDN.Intrinsicrisk

factorsforexercise-relatedinjuriesamongmaleandfemale armytrainees.AmJSportsMed.1993;21(5):705–10.

17.PesterS,SmithPC.Stressfracturesinthelowerextremitiesof soldiersinbasictraining.OrthopRev.1992;21(03):

297–303.

18.BolinD,KemperA,BrolinsonG.Currentconceptsinthe evaluationandmanagementofstressfractures.CurrRep SportMed.2005;4(6):295–300.

19.MoriS,BurrDB.Increasingintracorticalremodelling followingfatiguedamage.Bone.1993;14(2):103–9. 20.RaaschWG,HerganDJ.Treatmentofstressfractures:the

fundamentals.ClinSportsMed.2006;25(1):29–36. 21.KorpelainenR,OravaS,KarpakkaJ,SiiraP,HulkkoA.Risk

factorsforrecurrentstressfractureinathletes.AmJSports Med.2001;29(3):304–10.

22.JoyEA,CampbellD.Stressfracturesinthefemaleathlete. CurrSportsMedRep.2005;4(6):323–8.

23.GardnerLIJr,DziadosJE,JonesBH,BrundageJF,HarrisJM, SullivanR,etal.Preventionoflowerextremitystress fractures:acontrolledtrialofashockabsorbentinsole.AmJ PublicHealth.1988;78(12):1563–7.

24.MilgromC,FinestoneA,LeviY,SimkinA,EkenmanI, MendelsonS,etal.Dohighimpactexercisesproducehigher tibialstrainsthanrunning?BrJSportsMed.2000;34(3):195–9. 25.PatelRD.Stressfractures:diagnosisandmanagementinthe

primarycaresettings.PediatrClinNAm.2010;81:9–27. 26.ShafferRA,RauhMJ,BrodineSK,TroneDW,MaceraCA.

Predictorsofstressfracturesusceptibilityinyoungfemale recruits.AmJSportsMed.2006;34(1):108–15.

27.MilgromC,FinestoneA,ShlamkovitchN,RandN,LevB, SimkinA,etal.Youthisariskfactorforstressfracture:a studyof783infantryrecruits.JBoneJointSurgBr. 1994;76(1):20–2.

28.ValimakiVV,AlfthanH,LehmuskallioE,LoyttyniemiE,Sahi T,SuominenH,etal.Riskfactorsforclinicalstressfractures inmalemilitaryrecruits:aprospectivecohortstudy.Bone. 2005;37(2):267–73.

29.MyburgKH,HutchinsJ,FataarAB,HoughSF,NoakesTD.Low bonedensityisanetiologicfactororstressfracturesin athletes.AnnInternMed.1990;113(10):754–9.

30.NievesJW,MelsopK,CurtisM.Nutritionalfactorsthat influencechangeinbonedensityandstressfracturerisk amongyoungfemalecross-countryrunners.PMR. 2010;2(8):740–50.

31.PoppKL,HughesJM,SmockAJ,NovotnySA,StovitzSD, KoehlerSM,etal.Bonegeometry,strength,andmusclesize inrunnerswithahistoryofstressfracture.MedSciSports Exerc.2009;41(12):2145–50.

32.GiladiM,MilgromC,SimkinA,DanonY.Stressfractures: identifiableriskfactors.AmJSportsMed.1991;19(6):647–52.

33.ManioliA2nd,GrahamB.Thesubtlecavusfoot:theunder pronator:areview.FootAnkleInt.2005;26(3):256–63. 34.PohlMB,MullineauxDR,MilnerCE,HamillJ,DavisIS.

Biomechanicalpredictorsofretrospectivetibialstress fracturesinrunners.JBiochem.2008;41(6):1160–5.

35.MaitraRS,JohnsonDL.Stressfractures.Clinicalhistoryand physicalexamination.ClinSportsMed.1997;16(2):

259–74.

36.FredericsonM,WunC.Differentialdiagnosisoflegpaininthe athlete.JAmPodiatrMedAssoc.2003;93(4):321–4.

37.RomaniWA,PerrinDH,DussaultRG,BallDW,KahlerDM. Identificationoftibialstressfracturesusingtherapeutic continuousultrasound.JOrthopSportsPhysTher. 2000;30(8):444–52.

38.IshibashiY,OkamuraY,OtsukaH,NishizawaK,SasakiT,Toh S.Comparisonofscintigraphyandmagneticresonance imagingforstressinjuriesofbone.ClinJSportMed. 2002;12(2):79–84.

39.SterlingJC,EdelsteinDW,CalvoRD,WebbR.Stressfractures intheathlete.Diagnosisandmanagement.SportsMed. 1992;14(5):336–46.

40.BennellK,BruknerP.Preventingandmanagingstress fracturesinathletes.PhysTherSport.2005;6:171–80. 41.FredericsonM,BergmanAG,HoffmanKL,DillinghamMS.

Tibialstressreactioninrunners.Correlationofclinical symptomsandscintigraphywithanewmagneticresonance imaginggradingsystem.AmJSportsMed.1995;23(4): 472–81.

42.StrauchWB,SlomianyWP.Evaluatingshinpaininactive patients.JMusculoskeletMed.2008;25:138–48.

43.ShinAY,MorinWD,GormanJD,JonesSB,LapinskiAS.The superiorityofmagneticresonanceimagingindifferentiating thecauseofhippaininenduranceathletes.AmJSportsMed. 1996;24(2):168–76.

44.DixonS,NewtonJ,TehJ.Stressfracturesintheyoungathlete: apictorialreview.CurrProblDiagnRadiol.2011;40(1): 29–44.

45.ZukotynskiK,CurtisC,GrantFD,MicheliL,TrevesST.The valueofSPECTinthedetectionofstressinjurytothepars interarticularisinpatientswithlowbackpain.JOrthopSurg Res.2010;5:13.

46.SofkaCM.Imagingofstressfractures.ClinSportsMed. 2006;25(1):53–62.

47.BruknerP,BennellK.Stressfracturesinfemaleathletes. Diagnosis,managementandrehabilitation.SportsMed. 1997;24(6):419–29.

48.FredericsonM,JenningsF,BeaulieuC,MathesonGO.Stress fracturesinathletes.TopMagnResonImaging.

2006;17(5):309–25.

49.VoloshinKW.Dynamicloadingduringrunningonvarious surfaces.HumanMovSci.1992;11:675–89.

50.MehalloCJ,DreznerJA,BytomskiJR.Practicalmanagement: nonsteroidalanti-inflammatorydrug(NSAID)useinathletic injuries.ClinJSportMed.2006;16:170–4.

51.WheelerP,BattME.Donon-steroidalanti-inflammatory drugsadverselyaffectstressfracturehealing?Ashortreview. BrJSportsMed.2005;39(2):65–9.

52.BurnsAS,LauderTD.Deepwaterrunning:aneffectivenon weightbearingexerciseforthemaintenanceoflandbased runningperformance.MilMed.2001;166(3):253–8. 53.JohanssonC,EkenmanI,TornkvistH,ErikssonE.Stress

fracturesofthefemoralneckinathletes:theconsequenceof adelayindiagnosis.AmJSportsMed.1990;18(5):524–8. 54.BennetMH,StanfordR,TurnerR.Hyperbaricoxygentherapy

forpromotingfracturehealingandtreatingfracturenon union.CochraneDatabaseSystRev.2005;25(1):

55.ShimaY,EngebretsenL,IwasaJ,KitaokaK,TomitaK.Useof bisphosphonatesforthetreatmentofstressfracturesin athletes.KneeSurgSportsTraumatolArthrosc. 2009;17(5):542–50.

56.EkenmanI.Donotusebisphosphonateswithoutscientific evidence,neitherinthetreatmentnorprophylactic,inthe treatmentofstressfractures.KneeSurgSportsTraumatol Arthrosc.2009;17(5):433–4.

57.HammondJW,HintonRY,CurlLA,MurielJM,LoveringRM. Useofautologousplateletrichplasmatotreatmusclestrain injuries.AmJSportsMed.2009;37(6):1135–42.