Leonor Furtado de Mendonça e Almeida

Acute Myelitis: 5 year- retrospective study

2011/2012Leonor Furtado de Mendonça e Almeida

Acute Myelitis: 5 year- retrospective study

Mestrado Integrado em Medicina

Área: Neurologia

Trabalho efetuado sob a Orientação de:

Dra. Joana da Cruz Guimarães Ferreira de Almeida

Trabalho organizado de acordo com as normas da revista:

Journal of Neurology

1

Índice

Página de Título e Resumo………2

Artigo………....3

Tabelas e Figuras……….10

Anexo I………13

2

Acute Myelitis: 5 year- retrospective study

Leonor Almeida1, Carlos Andrade2, Joana Guimarães3, Carolina Garret4

Abstract:

Aim: To analyze demographic, clinical and paraclinical data of a cohort with first episode of acute

myelitis in a Portuguese hospital, as any description in the Portuguese population was found in literature. Describe the differences between myelitis associated and not associated with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Methods: 5 year- retrospective study based on medical records of admitted patients with a spinal cord

syndrome. Patients with age above 18 and inflammatory etiologies were included.

Results: 74 myeolopathies were identified but only 30 myelitis were included. In myelitis group, the final

diagnosis were: clinically isolated syndrome, MS, systemic lupus erythematosus, post-infectious myelitis and idiopathic form. Differences statistically significant between the groups were found in these subsets: presence of autonomic symptoms and gait autonomy at the onset, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results and longitudinal extension in spinal cord MRI. The recurrence of myelitis was also different among groups. The diagnostics groups were further classified in acute myelitis associated with MS and other acute myelitis. The statistically significant differences found among these groups were the same as in the groups described above. The neurological disability at the end of the follow-up was correlated with motor symptoms, hyperreflexia and visual evoked potencials with increased latencies and inversely correlated with an autonomous gait at the onset.

Conclusion: The principal aim of describing an acute myelitis cohort in Portuguese population was

accomplished. In order to make a better characterization enabling more accurate application of diagnostic criteria and treatment options, multicentre studies should be performed.

Key Words: inflammatory myelopathy, acute transverse myelitis, demyelinative myelitis, multiple

sclerosis

1- Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto.

Alameda Professor Hernâni Monteiro, 4200 Porto, Portugal Telephone and Fax: +351225511200

E-mail: leonor.fma@gmail.com

2- Neurology Department, Centro Hospitalar de São João E.P.E.

3- Neurology Department, Centro Hospitalar de São João E.P.E., Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto 4- Neurology Department, Centro Hospitalar de São João E.P.E., Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto

3

1. Introduction

Acute transverse myelopathy is a clinical definition of an acute neurological condition that reflects impairment of spinal cord function. [33] It results in loss of motor, sensory and autonomic functions below the level of the lesion [27], indicating the need of urgent therapy. [5] The lesion typically spans multiple vertebral segments and is not radiologically or pathologically transverse; the term transverse has been retained over decades because of the importance of a spinal sensory level in making the diagnosis.[29]

Although anatomically speaking spinal cord syndromes are well-defined, they have an extensive list of differential diagnosis.

First of all, it is important to rule out, by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), a compressive etiology by disc herniation, a tumor metastasis or spondylolisthesis, because a structural cause needs immediate neurosurgical evaluation.

Beyond the compressive etiology, myelopathies can occur due to inflammatory and non-inflammatory causes. The latter includes vascular, radiation, metabolic, neoplastic and paraneoplastic etiologies. [1, 13] The former can include systemic autoimmune disorders (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [17], Sjögren syndrome [3, 12], antiphospholipid antibody syndrome [20], mixed connective tissue disease [22], systemic sclerosis [35], ankylosing spondilitis [23], and sarcoidosis [18]), infections [1, 13, 27] and primary central nervous system demyelinating disorders [1].

Even among the last group there are several differential diagnosis, such as Multiple Sclerosis (MS), Neuromyelitis optica (NMO), Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis and the idiopathic form [9], which can be the ultimate diagnosis despite the extensive work-up.

A lumbar puncture should be performed to distinguish between inflammatory and non inflammatory myelopathy. If the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) shows moderate pleocytosis or increased immunoglobulin G (IgG) index and gadolinium enhancement is seen in spinal cord MRI, an inflammatory cause should be suspected and the extent of demyelination should be measured. [1]

The management of these patients is made in emergency care units with high-dose intravenous steroid therapy [16] or plasmapheresis, in case of severe demyelination [15].

Independent of etiology, the prognosis of these patients is highly variable and unpredictable. A division can be made in three groups: one third completely recovers, one third presents residual symptoms and the remaining have no improvement at all [25].

We didn’t find any description of this syndrome in the Portuguese population in literature, so the aim of our study is describing a group of patients admitted with the first episode of an non infectious inflammatory myelopathy, ie non infectious myelitis, in a Portuguese hospital and analyze the demographic, clinical and paraclinical data, in order to characterize them and correlate the findings with their outcome.

2. Patients and methods

A retrospective, descriptive and analytical study will be carried based on medical records of admitted patients with a spinal cord syndrome, between 01/01/2007 and 31/12/2011, in Neurology department of Centro Hospitalar de São João, E.P.E., Porto, Portugal.

4

Potential study subjects were identified by querying the inpatient database for different groups of discharge diagnosis: Encephalitis, myelitis and encephalomyelitis; spino-cerebellar diseases; diseases of the spinal cord not categorized in other group (NCOG); multiple sclerosis; demyelinating diseases NCOG; paralytic syndromes NCOG.2.1 Definition of cases

The enrolled patients had sensory (paresthesias, dysesthesias, hypoaesthesias, sensory level), motor (paraparesis, tetraparesis, monoparesis, hemiparesis) and/or autonomic (increased urinary urgency, bowel or bladder incontinence, difficulty or inability to void, incomplete evacuation or bowel constipation)[28] initial symptoms compatible with a spinal cord syndrome with progression from onset to nadir of 4 hours to 21 days[1]. Patients whose symptoms reach maximal severity in less than four hours from onset are presumed to have an ischemic etiology [1], therefore out of the scope of this study.

Patients matching the clinical criteria of spinal cord syndrome, as previously described, with age above 18 were included in the study.

The compressive, vascular, neoplastic, paraneoplastic, metabolic, infectious and radiation etiologies were excluded from the final evaluation and characterization of the cases of myelitis.

The initial diagnosis of acute transverse myelitis after the follow-up were categorized in subgroups according to the different etiologies.

2.2. Data collection 2.2.1. Clinical data

The following data was collected from Medical Charts: gender, age, date of admission and discharge, motive of admission, neurological exam aspects, previous diseases relevant to the case, family history of neurological disease, final diagnosis, therapeutics and evolution of the patient.

The dysfunction was staged with Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [19] and this classification was revised by a neurologist specialized in demyelinating diseases and certified by Neurostatus e-Test. In order to compare the last visit EDSS in patients with different time follow-ups, this score was converted to Multiple Sclerosis Severity Score (MSSS).[26]

2.2.2 Supplementary exams

Infectious diseases screening tests were performed in most cases. Serology for antibodies in serum to

Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) 1 and 2, Varicela Zoster Virus (VZV), Human T-cell Lymphotropic Virus-1, Borrelia spp, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), hepatitis B and C and Mycoplasma were

accomplished. Serologies and/or Polimerase Chain Reaction (PCR) in CSF were also carried out to

Borrelia spp, Treponema pallidum, Mycobacterium Tuberculosis, M. pneumoniae, HSV-1, HSV-2, Human Herpes virus-6, Enterovirus, HIV, Epstein-Barr Virus, Cytomegalovirus, VZV and Toxoplasma gondii.

Auto-immune diseases were screened by anti-nuclear antibodies, anti double stranded DNA antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-extractable nuclear antigens antibodies and circulating imunocomplexes

5

assays. Angiotensin converting enzyme was also titrated in CSF and vitamins B12 and E and copper levels were dosed in serum. Thyroid function tests, as well as anti-thyroid antibodies, were also requested. Brain MRI was classified in three groups according to the Barkoff/ Tintore criteria [4, 34] : normal, suggestive of MS (≥3 present criteria) or non suggestive of MS (< 3 criteria).Spinal cord MRI was analyzed by number of lesions, their longitudinal and transversal localization and extension, signal in T2-weighed scans, enhancement by gadolinium contrast and swelling of the cord. The first scan was carried during the acute phase.

Visual evoked potentials (VEP) were evaluated in most of the patients and subdivided in normal and increased latencies.

Inflammatory signs in CSF were assessed by number of cells (pleocytosis ≥10 total cells/mm3)[31], IgG index (≥0,6) and the presence of oligoclonal IgG bands (OCB).

Serum NMO-IgG antibodies were tested when there was a suspicion of a NMO spectrum disorder by ELISA, using a commercial sampling kit (INNOTEST AQP4Ab ELISA).

2.3. Statistical analysis

The data was saved and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 software program; missing values were excluded from the analysis. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviation or as medians with range. The different diagnostic groups were compared using Mann-Whitney U, Krushkal-Wallis, chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. p values <0,05 were considered statistically significant.

2.4. Ethical aspects

The study started after approval by Ethics Committee for Health of Centro Hospitalar de São João, E.P.E..

3. Results

After querying the inpatient database, 451 patients were found. However, after excluding patients under 18 years old, absence of a true spinal cord syndrome and presentations explained by a disease diagnosed before 2007, only 74 cases of myelopathies remained. Of this 74, only 30 myelitis were included in the study, following the exclusion of compressive spondylotic (n=18), associated with radiotherapy (n=1), vascular (n=8), subacute combined degeneration (n=8), paraneoplastic (n=3) and infectious (n=6) etiologies. Among the last ones, four cases of Neuroborreliosis, one HSV-1 and one HTLV-1 CNS infections were identified (Figure 1).In Myelitis patients group, five patients (16,7%) had the diagnosis of clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), fourteen (46,7%) of multiple sclerosis (MS), one (3,3%) of systemic lupus erythematosus, four (13,3%) of post-infectious myelitis and six (20%) with the idiopathic form. One patient in the MS group was diagnosed with primary progressive subtype.

3.1. Clinical Findings

Of the 30 myelitis patients, 16 (53,3%) were female and 14 (46,7%) were male and all of them were Caucasian. Onset of the disease occurred within a median of 7 days (ranging from 1 to 21) at the mean

6

age of 36,7 ±11,15 years. The most frequent symptoms were sensory disturbances (96,7%): hiposthesias in 21 (70%), disesthesias in 10 (33,3%), paresthesias in 14 (46,7%) and sensory level in 18 (60%). Motor symptoms were present in 18 cases (60%): hemiparesis- 3(10%); monoparesis- 3 (10%); paraparesis- 8 (26,7%) and tetraparesis- 4 (13,3%). Bilaterality of symptoms was found in 18 (60%). Hyperreflexia was present in 13 (43,3%) patients and 7 (23,3%) were unable to walk. Six patients (43,3%) referred pain and only 3 (10%) had a positive L’Hermitte sign. The median of the follow-up time (between first episode and last ambulatory visit) was 10 months (range:2-58).Eight patients (26,7%) had recurrence of the myelitis, seven from the MS group and one from the IATM group, within a median time of 4,5 months (range: 1-11). Two other patients from the MS group had non spinal relapses, one 17 months after and other 5 months after; both had motor symptoms compatible with encephalic lesions.

From the 6 patients who remained diagnosed as idiopathic, two completely fulfilled the diagnostic criteria from Transverse Acute Myelitis Consortium Working Group[1]. Two didn’t have bilateral symptoms but had instead an hemi-level, hence matching the criteria for acute partial transverse myelitis proposed by Scott et al.[32] The other two did have bilateral symptoms, however have not shown a clearly defined sensory level.

Only 9 patients (30%) had complete recovery, nevertheless the median EDSS at discharge was 1.5 (0-7.0) and the mean MSSS at the last follow-up visit was 2,77 (0,35-9,59).

All but 3 patients were treated with methylprednisolone (1g/d for 5 days), in cases of poor steroid response this treatment was followed by IV immunoglobulins (3 cases), plasmapheresis (2 cases), azathioprine (one) and cyclophosphamide (one).

3.2 Supplementary tests

All patients were submitted to at least one MRI scan of the spinal cord during the acute phase of the disease and, with one exception, an abnormal scan was found in all patients. 65,5% had a single lesion and 34,5% had multiple lesions (all lengthening ≤ 2 cord segments). 20,7% had a longitudinally extensive myelitis (≥3 cord segments) and 79,3% had a lesion spanning ≤ 2 vertebral segments. Eleven patients (36,7%) had lesion/lesions located in the cervical spinal cord, eight (26,7%) with thoracic location, seven (23,3%) with both cervical and thoracic, two (6,6%) with sacral and one patient with a lesion extending by the all length of the cord. In transversal section, 23,3% had centromedullary lesions, 46,7% peripheral lesions, 13,3% holocord lesions, 6,7% had a mixed type. Eleven ( 37,9%) patients presented with cord swelling and twenty-one (72,4%) with gadolinium enhancement.

A Brain MRI was also taken in all the patients with 6 (20%) of them having a normal scan, 6 (20%) having an abnormal scan but with less than 3 Barkoff/ Tintore criteria [4, 34] and 18 (60%) with 3 or more criteria present.

In CSF analysis, 11/30 (36,7%) showed pleocytosis, 19/25 (76%) an elevated IgG index and 16/28 (57,1%) positive OCB.

VEPs showed increased latencies in 5/23 (21,7%) patients. Of the 7 NMO-IgG antibodies requested, 6 were negative and one isn’t available yet.

7

3.3 Comparisons between groups

Table 1 shows the data for this study sample. There were no statistically significant differences between the diagnostic groups with respect to gender, age at the onset, symptoms (except autonomic symptoms (p=0,04) and gait autonomy (p=0,028)), CSF analysis including IgG index and OCB, VEP results and disability measured by EDSS at the onset, at discharge and at the end of follow-up by MSSS. Differences statistically significant between the groups were found in brain MRI (p=0,000) results and in the longitudinal extension (p=0,03) in spinal cord MRI. The recurrence of myelitis was also different among groups (p=0,008).

In order to understand the differences the diagnostics groups were further classified in acute myelitis associated with MS (AM-MS) and other acute myelitis (AM-O), either associated with other diseases or the idiopathic form. The patients with CIS were included in AM-MS group, because they were isolated in time, but all of them had dissemination in space according to the 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria.[24] The statistically significant differences found among AM-MS and AM-O groups were the same found in the groups described above (Table 2). Inability to deambulate is negatively associated with MS (OR=0,046), so was the presence of autonomic symptoms (OR=22,67). The differences in MRI, brain and spinal cord, were the same, as well.

The recurrence of symptomatic episodes was associated with AM-MS group (table 2) and with EDSS>2.5 at the onset ( p=0,018; OR=9,6 (1,48-62,16) ).

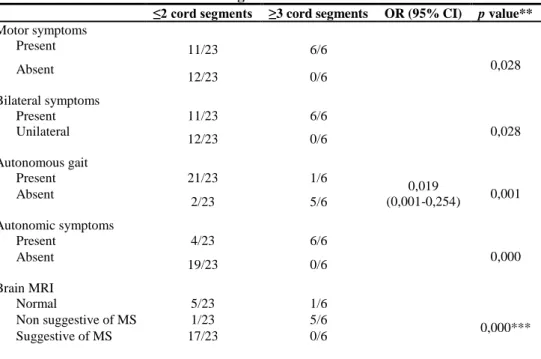

Longitudinally extensive cord lesions were strongly associated with presence of motor (p=0,028) and autonomic (p=0,000) manifestations and symmetrical symptoms (p=0,028), loss of fully ambulatory capacity (p=0,001) and absence of brain MRI suggestive of MS (p=0,000). (table 3)

At discharge from the hospital, EDSS>2.5 was only associated to positive OCB in CSF (p=0,028). (Table 4) The neurological disability at the end of the follow-up measured by MSSS superior to 2.5 was correlated with motor symptoms (p=0,002), hyperreflexia (OR=12)and VEP with increased latencies (OR=20) and inversely correlated with an autonomous gait at the onset (OR=0,111). (Table 5)

4. Discussion

This study describes the clinical course of 30 patients with first episode of acute myelitis. Diagnosis of MS was the most prevalent and its percentage superior to the ones found in recent studies[2, 6, 7, 21], despite similar presentations in others [8, 10]. This finding probably dues to the inclusion of patients with partial myelitis, without bilateral symptoms or a clearly defined sensory level as advocated by Transverse Myelitis Consortium Working Group.[1] These weren’t applied as inclusion criteria, because we didn’t want to exclude any kind of inflammatory myelopathy, except for th infectious etiologies, once this is the first Portuguese population description of this syndrome. We didn’t find any NMO case, which is very uncommon [2, 6, 7, 21]; presumably this pathology is even less ordinary in our population, since, as far as we are concerned, there is only one described case in literature in the Portuguese adult population.[11] Demographic differences were not found between groups. Although they have been described [8, 30], they are currently not useful in distinguishing causes of myelitis, according to an evidence based guideline recently released.[31]

8

The differences found among groups (five initial diagnostic groups and AM-MS/AM-O), correlating MS positively with an abnormal brain MRI with ≥3 Barkhof criteria, multiple and longitudinal small lesions in spinal MRI and recurrence of symptomatic myelitis, and negatively with loss of gait autonomy and autonomic symptoms, were as the expected.[32] The longitudinal extension of the spinal lesions was associated with the severity of manifestations and inversely associated with brain MRI suggestive of MS, although there was no correlation with long term disability as it was shown by other groups.[6, 21] However, this may be due to the reduced number of patients with longitudinal extensive myelitis.Superior neurological impairment, at hospital discharge, was associated with negative OCB and, at the end of the follow-up, with presence of motor symptoms, as was found by Gajofatto at al.[10] Hyperreflexia, inability to walk autonomously at the onset and VEP with increased latencies were also associated with MSSS superior to 2.5 at the end of the follow-up. Despite the findings of statistically significance, we don’t know if they are reproducible owing to the small sample size.

This study has several limitations. The reduced number of cases is the strongest limitation in our point of view, however as acute transverse myelitis is a rare presentation it is very difficult to have large cohorts in a single hospital. The fact that it is retrospective hampers the uniformity in supplementary testing. For example we didn’t report the results of somatosensory evoked potentials which once normal can predict better prognosis.[14] Nonetheless our principal aim was accomplished since we characterize demographically, clinically and paraclinically a Portuguese myelitis cohort. In order to understand if our findings are reproducible and indeed correlate with the outcome of patients, other studies should be performed. We appeal to multicentre studies, so that better characterization of our population is achieved and the application of diagnostic criteria and treatment options are more accurate and standardized.

Conflict of interests

None.Acknowledgments

Doctor Joana Lima Bastos, for the help with statistical analysis.

References

1. (2002) Proposed diagnostic criteria and nosology of acute transverse myelitis. Neurology 59:499-505

2. Alvarenga MP, Thuler LC, Neto SP, Vasconcelos CC, Camargo SG, Papais-Alvarenga RM (2010) The clinical course of idiopathic acute transverse myelitis in patients from Rio de Janeiro. Journal of neurology 257:992-998

3. Anantharaju A, Baluch M, Van Thiel DH (2003) Transverse myelitis occurring in association with primary biliary cirrhosis and Sjogren's syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 48:830-833

4. Barkhof F, Filippi M, Miller DH, Scheltens P, Campi A, Polman CH, Comi G, Ader HJ, Losseff N, Valk J (1997) Comparison of MRI criteria at first presentation to predict conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis. Brain : a journal of neurology 120 ( Pt 11):2059-2069

5. Brinar VV, Habek M, Zadro I, Barun B, Ozretic D, Vranjes D (2008) Current concepts in the diagnosis of transverse myelopathies. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 110:919-927

6. Chaves M, Rojas JI, Patrucco L, Cristiano E (2011) Acute transverse myelitis in Buenos Aires, Argentina. A retrospective cohort study of 8 years follow up. Neurologia (Barcelona, Spain)

7. de Seze J, Lanctin C, Lebrun C, Malikova I, Papeix C, Wiertlewski S, Pelletier J, Gout O, Clerc C, Moreau C, Defer G, Edan G, Dubas F, Vermersch P (2005) Idiopathic acute transverse myelitis: application of the recent diagnostic criteria. Neurology 65:1950-1953

8. de Seze J, Stojkovic T, Breteau G, Lucas C, Michon-Pasturel U, Gauvrit JY, Hachulla E, Mounier-Vehier F, Pruvo JP, Leys D, Destee A, Hatron PY, Vermersch P (2001) Acute myelopathies: Clinical, laboratory and outcome profiles in 79 cases. Brain : a journal of neurology 124:1509-1521

9. Eckstein C, Saidha S, Levy M (2011) A differential diagnosis of central nervous system demyelination: beyond multiple sclerosis. Journal of neurology

9

10. Gajofatto A, Monaco S, Fiorini M, Zanusso G, Vedovello M, Rossi F, Turatti M, Benedetti MD (2010) Assessment ofoutcome predictors in first-episode acute myelitis: a retrospective study of 53 cases. Archives of neurology 67:724-730 11. Guimaraes J, Sa MJ (2007) Devic disease with abnormal brain magnetic resonance image findings: the first Portuguese

case. Archives of neurology 64:290-291; author reply 291

12. Hummers LK, Krishnan C, Casciola-Rosen L, Rosen A, Morris S, Mahoney JA, Kerr DA, Wigley FM (2004) Recurrent transverse myelitis associates with anti-Ro (SSA) autoantibodies. Neurology 62:147-149

13. Jacob A, Weinshenker BG (2008) An approach to the diagnosis of acute transverse myelitis. Semin Neurol 28:105-120 14. Kalita J, Misra UK, Mandal SK (1998) Prognostic predictors of acute transverse myelitis. Acta neurologica Scandinavica

98:60-63

15. Keegan M, Pineda AA, McClelland RL, Darby CH, Rodriguez M, Weinshenker BG (2002) Plasma exchange for severe attacks of CNS demyelination: predictors of response. Neurology 58:143-146

16. Kennedy PG, Weir AI (1988) Rapid recovery of acute transverse myelitis treated with steroids. Postgrad Med J 64:384-385

17. Krishnan AV, Halmagyi GM (2004) Acute transverse myelitis in SLE. Neurology 62:2087-

18. Kumar N, Frohman EM (2004) Spinal neurosarcoidosis mimicking an idiopathic inflammatory demyelinating syndrome. Archives of neurology 61:586-589

19. Kurtzke JF (1983) Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 33:1444-1452

20. Lee DM, Jeon HS, Yoo WH (2003) Transverse myelitis in a patient with primary antiphospholipid syndrome. Yonsei Med J 44:323-327

21. Li R, Qiu W, Lu Z, Dai Y, Wu A, Long Y, Wang Y, Bao J, Hu X (2011) Acute transverse myelitis in demyelinating diseases among the Chinese. Journal of neurology 258:2206-2213

22. Mok CC, Lau CS (1995) Transverse myelopathy complicating mixed connective tissue disease. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 97:259-260

23. Oh DH, Jun JB, Kim HT, Lee SW, Jung SS, Lee IH, Kim SY (2001) Transverse myelitis in a patient with long-standing ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 19:195-196

24. Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, Clanet M, Cohen JA, Filippi M, Fujihara K, Havrdova E, Hutchinson M, Kappos L, Lublin FD, Montalban X, O'Connor P, Sandberg-Wollheim M, Thompson AJ, Waubant E, Weinshenker B, Wolinsky JS (2011) Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Annals of neurology 69:292-302

25. Ropper AH, Poskanzer DC (1978) The prognosis of acute and subacute transverse myelopathy based on early signs and symptoms. Annals of neurology 4:51-59

26. Roxburgh RH, Seaman SR, Masterman T, Hensiek AE, Sawcer SJ, Vukusic S, Achiti I, Confavreux C, Coustans M, le Page E, Edan G, McDonnell GV, Hawkins S, Trojano M, Liguori M, Cocco E, Marrosu MG, Tesser F, Leone MA, Weber A, Zipp F, Miterski B, Epplen JT, Oturai A, Sorensen PS, Celius EG, Lara NT, Montalban X, Villoslada P, Silva AM, Marta M, Leite I, Dubois B, Rubio J, Butzkueven H, Kilpatrick T, Mycko MP, Selmaj KW, Rio ME, Sa M, Salemi G, Savettieri G, Hillert J, Compston DA (2005) Multiple Sclerosis Severity Score: using disability and disease duration to rate disease severity. Neurology 64:1144-1151

27. Sa MJ (2009) Acute transverse myelitis: a practical reappraisal. Autoimmun Rev 9:128-131

28. Sakakibara R, Hattori T, Yasuda K, Yamanishi T (1996) Micturition disturbance in acute transverse myelitis. Spinal cord 34:481-485

29. Scott TF (2007) Nosology of idiopathic transverse myelitis syndromes. Acta neurologica Scandinavica 115:371-376 30. Scott TF, Bhagavatula K, Snyder PJ, Chieffe C (1998) Transverse myelitis. Comparison with spinal cord presentations of

multiple sclerosis. Neurology 50:429-433

31. Scott TF, Frohman EM, De Seze J, Gronseth GS, Weinshenker BG (2011) Evidence-based guideline: clinical evaluation and treatment of transverse myelitis: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 77:2128-2134

32. Scott TF, Kassab SL, Singh S (2005) Acute partial transverse myelitis with normal cerebral magnetic resonance imaging: transition rate to clinically definite multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England) 11:373-377 33. Scotti G, Gerevini S (2001) Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of acute transverse myelopathy. The role of

neuroradiological investigations and review of the literature. Neurol Sci 22 Suppl 2:S69-73

34. Tintore M, Rovira A, Martinez MJ, Rio J, Diaz-Villoslada P, Brieva L, Borras C, Grive E, Capellades J, Montalban X (2000) Isolated demyelinating syndromes: comparison of different MR imaging criteria to predict conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology 21:702-706

35. Torabi AM, Patel RK, Wolfe GI, Hughes CS, Mendelsohn DB, Trivedi JR (2004) Transverse myelitis in systemic sclerosis. Archives of neurology 61:126-128

10

Table 1 Characteristics of the study subjects

Characteristics MS CIS PI SLE IATM p

value* Gender (F:M) 8:6 3:2 0:4 1:0 4:2 0,196 Age at onset 33,07 (10,042) 36,60 (13,903) 48,50 (13,178) 36 a 37,50 (7,176) 0,277** Motor symptoms Tetraparesis Paraparesis Hemiparesis Monoparesis 9/14 3 2 3 1 2/5 0 1 0 1 3/4 1 2 0 0 1/1 0 1 0 0 3/6 0 2 0 1 0,693 0,697 Hyperreflexia 8/14 2/5 1/4 1/1 1/6 0,319 Sensory symptoms 13/14 5/5 4/4 1/1 6/6 0,881 Paresthesias 7/14 2/5 1/4 1/1 3/6 0,722 Dysesthesias 5/14 2/5 1/4 0/1 3/6 0,944 Hyposthesias 11/14 3/5 4/4 1/1 3/6 0,205 Sensory level 8/14 3/5 2/4 1/1 4/6 0,911 Bilateral symptoms 8/14 1/5 4/4 1/1 4/6 0,145 Autonomous gait 13/14 5/5 2/4 0/1 3/6 0,028 Autonomic symptoms 2/14 0/5 4/4 1/1 3/6 0,04 Pain 2/12 0/5 2/4 0/1 2/6 0,319 EDSS at onset 3.0 (1.0-7.0) 1.5 (1.0-3.0) 3.0 (1.0-7.0) 2.5 a 4.0(1.0-8.0) 0,368**

Spinal cord MRI

Single lesion 6/13 2/5 4/4 1/1 6/6 0,052 Multiple lesions 7/13 3/5 0/4 0/1 0/6 Longitudinal extension ≤ 2 cord segments 13/13 5/5 1/4 0/1 4/6 0,03 ≥ 3 cord segments 0/13 0/5 3/4 1/1 2/6 Gadolinium Enhancement 10/13 4/5 2/4 0/1 5/6 0,371 Cord swelling 4/13 3/5 2/4 0/1 2/6 0,694 Brain MRI Normal 0/14 0/5 1/4 0/1 5/6 0,000 Suggestive of MS 13/14 5/5 0/4 0/1 0/6 Non suggestive of MS 1/14 0/5 3/4 1/1 1/6 CSF analysis Pleocytosis 5/14 2/5 3/4 0/1 1/6 0,383 OCB + 10/14 3/5 1/3 - 2/6 0,352 IgG index >0,6 9/11 4/5 2/3 - 4/6 0,878 VEPs Normal 10/13 3/4 0/1 1/1 4/4 0,284 Increased latencies 3/13 1/4 1/1 0/1 0/4 EDSS at discharge 1.5 (0-3.5) 1.0 (0-1.5) 2.0 (0-2.5) 0 a 1.5 (0-7.0) 0,375** Full Recovery 2/14 2/5 1/3 1/1 3/6 0,262 Recurrence of myelitis 9/13 0 0/3 0/1 1/6 0,008 MSSS 2,9662 (2,04159) 1,5820 (1,0063) 2,99933 (2,64379) - a 2,9667 (3,50724) 0,625**

Abbreviations: MS: multiple sclerosis; CIS: clinically isolated syndrome; PI: post-infectious; SLE:nSystemic Lupus Eritematous; IATM: idiopathic acute transverse myelitis; Gender (F:M)- Female:Male; OCB +: positive oligoclonal bands in cerebrospinal fuid.

*Calculated using chi-square test **Calculated using Krushkall-Wallis test

11

Table 2 – Variables associated with MS group

AM-MS AM-O OR (95% CI)* p value**

Autonomous gait Absent 1 6 0,046 (0,004-0,479) 0,04 Present 18 5 Autonomic symptoms Absent 17 3 22,67 (3,14-1633,63) 0,001 Present 2 8 Brain MRI Normal 0 6 0,000 Non suggestive of MS 1 5 Suggestive of MS 18 0 Spinal cord MRI

Single lesion 8 11 0,003 Multiple lesions 10 0 Longitudinal extension ≤ 2 cord segments 18 5 0,001*** ≥ 3 cord segments 0 6 Recurrence of myelitis Absent Present 8 9 9 1 0,0099 (0,010-0,961) 0,042

Abbreviations: OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval

* Risk of having MS with the presence of certain characteristics was calculated by an OR with 95% CI. These were wide due to the small sample size.

**Calculated by Fisher exact test or ***chi-square test

Table 3- Variables associated with longitudinal extension of cord lesions

≤2 cord segments ≥3 cord segments OR (95% CI) p value**

Motor symptoms Present 11/23 6/6 0,028 Absent 12/23 0/6 Bilateral symptoms Present 11/23 6/6 0,028 Unilateral 12/23 0/6 Autonomous gait Present 21/23 1/6 0,019 (0,001-0,254) 0,001 Absent 2/23 5/6 Autonomic symptoms Present 4/23 6/6 0,000 Absent 19/23 0/6 Brain MRI Normal 5/23 1/6 0,000*** Non suggestive of MS 1/23 5/6 Suggestive of MS 17/23 0/6

* Risk of having a longitudinal extensive lesion was calculated by an OR with 95% confidence interval (CI) ** values calculated using chi-square and Fisher exact test or *** chi-square test

Table 4 - Variables associated with disability at discharge after first episode

EDSS ≤ 2.5 EDSS > 2.5 p value*

OCB

Positive 15/23 0/4

0,028 Negative

8/23 4/4

12

Table 5 - Variables associated with disability at the end of the follow-up

MSSS ≤ 2.5 MSSS > 2.5 OR (95% CI) of MSSS > 2.5* p value** Motor symptoms Present 8/20 10/10 0,002 Absent 12/20 0/10 Autonomous gait Present 18/20 5/10 0,111 (0,016-0,755) 0,026 Absent 2/20 5/10 Hyperreflexia Present 5/20 8/10 12 (1,885-76,376) 0,007 Absent 15/20 2/10 VEP Increased latencies 1/16 4/7 20 (1,613-247,981) 0,017 Normal 15/16 3/7

Abbreviations: VEP- Visual Evoked Potentials

* Risk of having a MSSS> 2.5 was calculated by an OR with 95% confidence interval (CI) ** values calculated using Fisher exact test

451 cases

Myelopathies

n =74

Myelitis

n =30

SCM

n =18

Vascular

n =8

SCD

n =8

Infectious

n =6

Paraneoplastic

n =3

Radiotherapy

n =1

HSV-1

N =1

HTLV-1

n =1

Neuroborreliosis

n =4

Figure 1- Diagram showing etiologies of the acute myelopathies included and excluded from the study

Abbreviations: SCM: Spondilotic Compressive Myelopathy; SCD: Subacute Combined Degeneration; HTLV-1: Human T-cell Lymphotropic Virus-1; HSV-1: Herpes Simplex Virus-1

13

Anexo I

14

Journal of Neurology publication criteria

Type of papers

o Declaration of Conflict of Interest is mandatory for all submissions.

o Please refer to the section "Integrity of research and reporting" in the Instructions for Authors.

o Papers must be written in English.

o Papers must not exceed 8 printed pages (20 type-written pages of 32 lines each) plus 8 figures, taking up no more than 3 printed pages altogether. Exception to this rule can be made only with the agreement of the Joint Chief Editors.

o Letters to the Editors will be considered for publications of brief communications or case reports; they should not contain more than 600 words, 1 figure, 1 table (or 2 of either), and 15 references.

Manuscript Submission

Submission of a manuscript implies: that the work described has not been published before; that it is not under consideration for publication anywhere else; that its publication has been approved by all co-authors, if any, as well as by the responsible authorities – tacitly or explicitly – at the institute where the work has been carried out. The publisher will not be held legally responsible should there be any claims for compensation.

Permissions

Authors wishing to include figures, tables, or text passages that have already been published elsewhere are required to obtain permission from the copyright owner(s) for both the print and online format and to include evidence that such permission has been granted when submitting their papers. Any material received without such evidence will be assumed to originate from the authors.

Online Submission

Authors should submit their manuscripts online. Electronic submission substantially reduces the editorial processing and reviewing times and shortens overall publication times. Please follow the hyperlink “Submit online” on the right

and upload all of your manuscript files following the instructions given on the screen.

Title Page

The title page should include: o The name(s) of the author(s) o A concise and informative title

o The affiliation(s) and address(es) of the author(s)

o The e-mail address, telephone and fax numbers of the corresponding author Abstract

Please provide an abstract of 150 to 250 words. The abstract should not contain any undefined abbreviations or unspecified references.

Keywords

Please provide 4 to 6 keywords which can be used for indexing purposes.

Text Formatting

Manuscripts should be submitted in Word.

o Use a normal, plain font (e.g., 10-point Times Roman) for text. o Use italics for emphasis.

15

o Do not use field functions.o Use tab stops or other commands for indents, not the space bar. o Use the table function, not spreadsheets, to make tables. o Use the equation editor or MathType for equations.

Note: If you use Word 2007, do not create the equations with the default equation editor but use the Microsoft equation editor or MathType instead.

Headings

Please use no more than three levels of displayed headings.

Abbreviations

Abbreviations should be defined at first mention and used consistently thereafter.

Footnotes

Footnotes can be used to give additional information, which may include the citation of a reference included in the reference list. They should not consist solely of a reference citation, and they should never include the bibliographic details of a reference. They should also not contain any figures or tables. Footnotes to the text are numbered consecutively; those to tables should be indicated by superscript lower-case letters (or asterisks for significance values and other statistical data). Footnotes to the title or the authors of the article are not given reference symbols.

Always use footnotes instead of endnotes.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments of people, grants, funds, etc. should be placed in a separate section before the reference list. The names of funding organizations should be written in full.

Scientific style

Generic names of drugs and pesticides are preferred; if trade names are used, the generic name should be given at first mention.

Citation

Reference citations in the text should be identified by numbers in square brackets. Some examples: 1. Negotiation research spans many disciplines [3].

2. This result was later contradicted by Becker and Seligman [5]. 3. This effect has been widely studied [1-3, 7].

Reference list

The list of references should only include works that are cited in the text and that have been published or accepted for publication. Personal communications and unpublished works should only be mentioned in the text. Do not use footnotes or endnotes as a substitute for a reference list.

The entries in the list should be numbered consecutively. o Journal article

Gamelin FX, Baquet G, Berthoin S, Thevenet D, Nourry C, Nottin S, Bosquet L (2009) Effect of high intensity intermittent training on heart rate variability in prepubescent children. Eur J Appl Physiol 105:731-738. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0955-8

Ideally, the names of all authors should be provided, but the usage of “et al” in long author lists will also be accepted:

Smith J, Jones M Jr, Houghton L et al (1999) Future of health insurance. N Engl J Med 965:325–329

16

Slifka MK, Whitton JL (2000) Clinical implications of dysregulated cytokine production. JMol Med. doi:10.1007/s001090000086 o Book

South J, Blass B (2001) The future of modern genomics. Blackwell, London o Book chapter

Brown B, Aaron M (2001) The politics of nature. In: Smith J (ed) The rise of modern genomics, 3rd edn. Wiley, New York, pp 230-257

o Online document

Cartwright J (2007) Big stars have weather too. IOP Publishing PhysicsWeb. http://physicsweb.org/articles/news/11/6/16/1. Accessed 26 June 2007

o Dissertation

Trent JW (1975) Experimental acute renal failure. Dissertation, University of California Always use the standard abbreviation of a journal’s name according to the ISSN List of Title Word Abbreviations, seewww.issn.org/2-22661-LTWA-online.php

For authors using EndNote, Springer provides an output style that supports the formatting of in-text citations and reference list.EndNote style (zip, 2 kB)

Tables

o All tables are to be numbered using Arabic numerals.

o Tables should always be cited in text in consecutive numerical order.

o For each table, please supply a table caption (title) explaining the components of the table. o Identify any previously published material by giving the original source in the form of a

reference at the end of the table caption.

o Footnotes to tables should be indicated by superscript lower-case letters (or asterisks for significance values and other statistical data) and included beneath the table body.

Artwork

For the best quality final product, it is highly recommended that you submit all of your artwork – photographs, line drawings, etc. – in an electronic format. Your art will then be produced to the highest standards with the greatest accuracy to detail. The published work will directly reflect the quality of the artwork provided.

Figure Lettering

o To add lettering, it is best to use Helvetica or Arial (sans serif fonts).

o Keep lettering consistently sized throughout your final-sized artwork, usually about 2–3 mm (8–12 pt).

o Variance of type size within an illustration should be minimal, e.g., do not use 8-pt type on an axis and 20-pt type for the axis label.

o Avoid effects such as shading, outline letters, etc. o Do not include titles or captions within your illustrations.

Figure Numbering

o All figures are to be numbered using Arabic numerals.

o Figures should always be cited in text in consecutive numerical order. o Figure parts should be denoted by lowercase letters (a, b, c, etc.).

o If an appendix appears in your article and it contains one or more figures, continue the consecutive numbering of the main text. Do not number the appendix figures, "A1, A2,

17

A3, etc." Figures in online appendices (Electronic Supplementary Material) should,however, be numbered separately.

Figure Captions

o Each figure should have a concise caption describing accurately what the figure depicts. Include the captions in the text file of the manuscript, not in the figure file.

o Figure captions begin with the term Fig. in bold type, followed by the figure number, also in bold type.

o No punctuation is to be included after the number, nor is any punctuation to be placed at the end of the caption.

o Identify all elements found in the figure in the figure caption; and use boxes, circles, etc., as coordinate points in graphs.

o Identify previously published material by giving the original source in the form of a reference citation at the end of the figure caption.

Figure Placement and Size

o When preparing your figures, size figures to fit in the column width.

o For most journals the figures should be 39 mm, 84 mm, 129 mm, or 174 mm wide and not higher than 234 mm.

o For books and book-sized journals, the figures should be 80 mm or 122 mm wide and not higher than 198 mm.

Permissions

If you include figures that have already been published elsewhere, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner(s) for both the print and online format. Please be aware that some publishers do not grant electronic rights for free and that Springer will not be able to refund any costs that may have occurred to receive these permissions. In such cases, material from other sources should be used.

Integrity of research and reporting

Ethical standards

Manuscripts submitted for publication must contain a statement to the effect that all human studies

have been approved by the appropriate ethics committee and have therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. It should also

be stated clearly in the text that all persons gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. Details that might disclose the identity of the subjects under study should be omitted.

The editors reserve the right to reject manuscripts that do not comply with the above-mentioned requirements. The author will be held responsible for false statements or failure to fulfill the above-mentioned requirements.

Conflict of interest

Authors must indicate whether or not they have a financial relationship with the organization that sponsored the research. This note should be added in a separate section before the reference list.

If no conflict exists, authors should state: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Both statements have also to be sent to the Editor-in-Chief together with the original manuscript when this is submitted. The forms can be downloaded at the end of this paragraph.

They have to be filled-in, printed, signed, scanned and uploaded as “Supplementary Material” to the original manuscript files.

Ethical Standards Agreement Form (pdf, 49 kB)