www.jped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Validation

of

a

subjective

global

assessment

questionnaire

夽

,

夽夽

Maiara

Pires

Carniel

a,∗,

Daniele

Santetti

a,

Juliana

Silveira

Andrade

a,

Bianca

Penteado

Favero

b,

Tábata

Moschen

c,

Paola

Almeida

Campos

d,

Helena

Ayako

Sueno

Goldani

e,

Cristina

Toscani

Leal

Dornelles

aaUniversidadeFederaldoRioGrandedoSul(UFRGS),PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil

bPontifíciaUniversidadeCatólicadoRioGrandedoSul(PUCRS),PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil

cCentroUniversitárioLaSalle(UNILASALLE),Canoas,RS,Brazil

dCentroUniversitárioFranciscano(UNIFRA),SantaMaria,RS,Brazil

eDepartmentofPediatrics,UniversidadeFederaldoRioGrandedoSul(UFRGS),PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil

Received23October2014;accepted11March2015 Availableonline17July2015

KEYWORDS Nutritional assessment; Children; Adolescents; Anthropometry; Validationstudies

Abstract

Objective: TovalidatetheSubjectiveGlobalNutritionalAssessment(SGNA)questionnairefor Brazilianchildrenandadolescents.

Methods: Across-sectionalstudywith242patients,aged30daysto13years,treatedin pedi-atricunitsofatertiaryhospitalwithacuteillnessandminimumhospitalizationof24h.After permissionfromtheauthorsoftheoriginalstudy,thefollowingcriteriawereobservedtoobtain thevalidationofSGNAinstruments:translationandbacktranslation,concurrentvalidity, pre-dictivevalidity,andinter-observerreliability.Thevariablesstudiedwereage,sex,weightand lengthatbirth,prematurity,andanthropometry(weight,height,bodymassindex,upperarm circumference,tricepsskinfold,andsubscapularskinfold).Theprimaryoutcomewas consid-eredastheneedforadmission/readmissionwithin30daysafterhospitaldischarge.Statistical testsusedincludedANOVA,Kruskal---Wallis,Mann---Whitney,chi-square,andKappacoefficient.

Results: AccordingtoSGNAscore,80%ofpatientswereconsideredaswellnourished,14.5% moderatelymalnourished,and5.4%severelymalnourished.Concurrentvalidityshowedaweak correlationbetweentheSGNAandanthropometricmeasurements(p<0.001).Regarding pre-dictivepower,themainoutcomeassociatedwithSGNAwaslengthofadmission/readmission.

夽 Pleasecitethisarticleas:CarnielMP,SantettiD,AndradeJS,FaveroBP,MoschenT,CamposPA,etal.Validationofasubjectiveglobal

assessmentquestionnaire.JPediatr(RioJ).2015;91:596---602.

夽夽

ThestudywasconductedatPostgraduatePrograminChildandAdolescentHealth,UniversidadeFederaldoRioGrandedoSul(UFRGS), PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:maiaracarniel@yahoo.com.br(M.P.Carniel). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2015.03.005

Secondaryoutcomesassociatedincludedthefollowing:lengthofstayattheunitafterSGNA, weight andlengthatbirth, andprematurity(p<0.05).The interobserverreliability showed goodagreementamongexaminers(Kappa=0.74).

Conclusion: This study validated the SGNA in thisgroup of hospitalizedpediatric patients, ensuringitsuseintheclinicalsettingandforresearchpurposesintheBrazilianpopulation. ©2015SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Avaliac¸ãonutricional; Crianc¸as;

Adolescentes; Antropometria; Estudosdevalidac¸ão

Validac¸ãodeumquestionáriodeavaliac¸ãonutricionalsubjetivaglobal

Resumo

Objetivo: Validar o questionário de Avaliac¸ão Nutricional Subjetiva Global (ANSG) para a populac¸ãodecrianc¸aseadolescentesbrasileiros.

Métodos: Estudotransversal,realizado com242pacientes, de30 diasa13anos, atendidos emunidadespediátricasdeumhospitalterciário,comdoenc¸asagudasetempode permanên-ciamínimade24horashospitalizados.Apósautorizac¸ãodosautoresdoestudooriginalforam realizadasasseguintesetapasparaobtenc¸ãodavalidac¸ãodosinstrumentosdeANSG:traduc¸ão (backtranslation),validadedecritérioconcorrenteepreditivaeconfiabilidadeinterobservador. As variáveis em estudo foram: idade, sexo,peso e comprimentoao nascer, prematuridade e antropometria (peso, estatura, índice de massa corporal, circunferência braquial, dobra cutâneatricipitaledobracutâneasubescapular).Odesfechoprincipalconsideradofoi neces-sidadede internac¸ão/reinternac¸ão até30 diasapósaalta hospitalar.Ostestes estatísticos utilizadosforam:ANOVA,Kruskal---Wallis,Mann---Whitney,Qui-quadradoecoeficienteKappa.

Resultados: Deacordocomaclassificac¸ãodoANSG80%dospacientesforamclassificadoscomo bemnutridos,14.5%moderadamentedesnutridose5.4%gravementedesnutridos.Avalidade concorrente mostrou fraca aregular correlac¸ão do ANSG com as medidas antropométricas utilizadas (p<0.001). Quantoao poderpreditivo, desfechoprincipal associado ao ANSG foi tempodeinternac¸ão/reinternac¸ão.Osdesfechossecundáriosassociadosforam:tempode per-manêncianaunidadeapósANSG,pesoecomprimentoaonascereprematuridade(p<0.05).A confiabilidadeinterobservadormostrouboaconcordânciaentreosavaliadores(Kappa=0.74).

Conclusão: EsteestudovalidouométododeANSGnessaamostradepacientespediátricos hos-pitalizados,possibilitando seuusoparafinsdeaplicac¸ãoclínicaedepesquisanapopulac¸ão brasileira.

©2015SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Todososdireitos reservados.

Introduction

Inrecentdecades,therehasbeenasignificantreductionin theprevalenceofworldwidemalnutritioninchildren.1

Nev-ertheless,deathratesduetoseveremalnutritioninchildren

undergoinghospitaltreatmentremainhigh.2---4Several

stud-ieshavereportedaprevalenceofmalnutritionrelatedtoan

underlyingdiseaseof6---51%inhospitalizedchildren.5---7

However, the lack of consensus regarding the

defini-tion,heterogeneousnutritionalscreeningmethods,andthe

fact that nutrition is not prioritized as part of patient

care are some of the factors responsible for the

under-recognition of malnutrition prevalence and its impact on

clinicalresults.Recently,anewdefinitionofhospital

malnu-tritioninchildrenhasbeenused.Thisdefinitionincorporates

theconceptsofchronicity,etiologyandpathogenesisof

mal-nutrition,itsassociationwithinflammation,anditsimpact

onbodyfunctionalalterations.8

Thus, it is crucialtoknow and monitor the nutritional

statusofhospitalizedchildren,tobetterunderstandfactors

contributingtotheoccurrenceofcomplications,increased

lengthofhospitalstay,and consequentincreasein health

systemcosts.5,9---11

Subjective nutritional assessment is an evaluation

method based on clinical judgment and has been widely

used to assess the nutritional status of adults for

clini-calresearchpurposes,7consideredapredictorofmorbidity

andmortality.12Itdiffersfromothernutritionalassessment

methodsbyencompassingnotonlybodycomposition

alter-ations but alsopatient functionalimpairment,13 assessing

thepossiblepresenceofnutritionalrisks,basedonclinical

historyandphysicalexamination.Itisasimple,fast,

inex-pensive,andnon-invasivemethodthatcanbeperformedat

thebedside.12

The questionnaire adapted by Secker andJeejeebhoy7

forthepediatricpopulationhasbeentermedtheSubjective

GlobalNutritionalAssessment(SGNA),andevaluatesthe

fol-lowing parameters:the child’s current height and weight

history,parentalheight,foodconsumption,frequencyand

duration of gastrointestinal symptoms, and current

func-tional capacity and recent alterations. It also associates

Thepresenceoffunctionalalterationsappearstobethe

determiningfactorintheoccurrenceofcomplications

asso-ciatedwithmalnutrition.Thus,itisofutmostimportanceto

attainearlydetectionofnutritionalriskthroughamethod

thatisadequate,sensitivetoidentifyearlyalterations,

spe-cificenoughtobechangedonlybynutritionalimbalances,

andcorrectedbasedonanutritionintervention.14

Considering the need to validate a reliable method of

nutritionalassessmentforchildrenandadolescentsinBrazil,

theaimofthisstudywastovalidatetheSGNAinapopulation

ofBrazilianchildrenandadolescents.

Methods

Population

Thiswasacross-sectionalstudycarriedoutwith242patients aged30daysto13 years,in thecity of PortoAlegre, RS, Southern Brazil. Patients were enrolled in the Pediatric Emergencyand Inpatient Units of Hospital de Clinicas de PortoAlegre,RS,consideringasastudyfactorthenutritional statusassessmentbasedonobjectiveandsubjectivedata. The analyzed outcomes were need for hospitaladmission (patientsfrom theemergency observation room)or read-mission(patientsfromthepediatricward).Datacollection occurredfromMay2012toJune2013.

Thestudyinclusioncriteriawerethefollowing:children and adolescents, aged30 days to 19 years, of both gen-ders,withclinicaldiagnosisofacutediseases15andminimum

lengthofstayof24hinthePediatricEmergencyand

Inpa-tientUnits.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: neuropsychomotor

development delay (according to parental information);

underlying chronic diseases (congenital malformations,

inborn errors of metabolism, heart disease, neuropathy,

liver disease, immunocompromised patients, children of

HIV+mothers);chronicuseofmedicationexceptforferrous

sulfate and multivitamins at prophylactic doses; hospital

admission in the 30-day period prior to the study

assess-ment;patientsyoungerthanonemonth;infectiousprocess

inthepastsevendays;incapacitytoperform

anthropomet-ricmeasurements;andpatientsandcaregiverswhodidnot

speak Portuguese.The clinical informationrelated tothe

underlying diseases were collected from medical records

andconfirmedbytheassistantmedicalteam.

The research project designed for the developmentof

thisstudywasapprovedbytheResearchEthicsCommittee

ofHospitaldeClínicasdePortoAlegre(ProjectNo.11-0339).

Parentsand/orguardianssignedaninformedconsentprior

tostudyenrollment.

Toolvalidationprocess

Initially permission was obtained from the authors to reproduce and use the SGNA questionnaires originating from the PhD thesis entitled ‘‘Nutritional Assessment in Children:AComparisonofClinicalJudgmentandObjective Measures.’’16 Next, the questionnaires were translated

through the back-translation method,17 according to

the following steps: first, translation from English into

Portuguese; subsequently, the new questionnaires were

translatedfromPortuguesebackintoEnglish.

At the third step, a comparison of the tools was

per-formed by a bilingual translator whose native language

is English, who verified whether the new questionnaires

wereaccurateaccordingtotheoriginalcontentand

struc-ture.Thestepsofthistranslationprocesswereperformed

bythreeindependenttranslators.Subsequently,translation

validationwasperformed,consisting ofthereliabilityand

validityassessment.

Studydesign

Afterresearchertrainingtostandardizecollectionof anthro-pometric measurements18 andSGNA questionnaire use,7,19

each child was assessed by two independent researchers

blinded to each other; one researcher collected

anthro-pometric data, whereas the other applied the SGNA

questionnaire. To test SGNA interobserver reproducibility,

61randomlyselectedpatients(25%ofthestudypopulation)

wereevaluatedbyathirdcollaborator,whoalsoappliedthe

SGNAquestionnaire.

Theobjectiveandsubjectivedatawerecollectedwithin

48h after patient hospital admission. Thirty days after

patient hospital discharge, a search was carried out in

the medical files to observe the outcome of need for

hospitaladmission/readmission. Datawere entered intoa

databaseusingMicrosoft Excelsoftware(Microsoft®,2007,

USA) and exported to SPSS (version 18.0, Chicago, USA).

AnthroandAnthroPlussoftware(version3.2.2,WorldHealth

Organization, Geneva, Switzerland) were used to assess

anthropometricdata.

Subjectiveglobalnutritionalassessment

Objectivenutritionalassessment

The following anthropometric measurements were ana-lyzed:weightandheight;bodymassindex(BMI);upperarm circumference (AC); triceps skinfold (TSF), and subscapu-lar skinfold (SSF). For children younger than 24 months, weightwasmeasuredwiththechildrenwearingnoclothes ordiapers.Childrenolderthan24monthsandadolescents wereweighed withagown andwithout shoes. AFilizola® electronicscale(Filizola®,SP,Brazil)wasusedtomeasure weight.

Height measurements were performed using a wood boardwithafixed bladeononesideandmoveableonthe other,thetopoftheheadonthefixedpart(WCS®,Brazil), withthemoveablepartarrangedtobeinparallelwiththe child’slegs.Inchildrenyoungerthan24months,thelength wasmeasured in the supinepositionby measuringwith a rulerattachedtotheboard.Childrenolderthan24months andadolescentsweremeasuredinthestandingpositionwith ananthropometricruler(WISO®,Brazil)fixedonthewalland mobilecursorgraduatedincentimeters.

AC measurementswere measured using a flexible and retractablefiberglassmeasuringtape,surroundingthe mid-dleportionofthenon-dominantarm,withthearmrelaxed. TSFmeasurementswereperformedintheposteriorregion ofthenon-dominantarm,paralleltothelongitudinalaxis, atmidpointbetweentheacromionandolecranon.SSF mea-surements were performed with the non-dominant arm relaxed at the side of the body, obliquely tothe longitu-dinalaxis,followingtheorientationoftheribs,locatedtwo centimetersbelowthelowerangleofthescapula.

The skinfolds were measured in triplicate using a sci-entific adipometer (Cescorf®, Brazil). All equipment was calibratedandthetechniquesusedtoobtainmeasurements were standardized.18 The anthropometric assessment and

nutritionalstatus classificationwere carriedout basedon

thefollowingcriteriaandtoolsoftheWHO20,21:

Childrenagedzerotofiveyears:theWHO’sAnthroPlus

software(version 3.2.2,2011, WorldHealthOrganization,

Geneva,Switzerland)wasused,whichdeterminesz-scores

fortheweight/height(W/H),weight/age(W/A),height/age

(H/A), body mass index/age (BMI/A), upper arm

circum-ference/age (AC/A), tricipital skinfold/age (TSF/A), and

subscapularskinfold/Age(SSF/A)ratios.

Children olderthan five years: the WHO’sAnthro Plus

software(version 3.2.2,2009, WorldHealthOrganization,

Geneva,Switzerland)wasused,whichdeterminesz-scores

for W/A, H/A, and BMI/A ratios. z-score data for AC/A,

TSF/A and SSF/A ratios were evaluated according to the

reference values of Frisancho.22 The premature infants

(n=18) were evaluated using the corrected age up to 2

years.23

Statisticalanalysis

Samplesizewascalculatedconsideringthemeansand stan-darddeviationofhospitallengthofstayfoundinthestudy bySeckerandJeejeebhoy,7of5.3±5.0daysforthegroup

ofwell-nourishedchildrenand8.2±10daysfor thegroup

of malnourishedchildren, witha power of 80%and a

sig-nificancelevelof0.05,resultinginatotalof236patients.

Therequiredsamplesizetotestinterobserverreliabilitywas

calculatedbasedontheKappavalueof 0.6,consideringa

powerof80% andsignificancelevelof 0.05,resultingina

subgroupof61patients.

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean and

standarddeviationormedianandinterquartilerange.

Cat-egoricalvariablesweredescribedasabsoluteandrelative

frequencies.One-way ANOVAwithposthocTukeytestwas

applied to compare means between groups. In case of

asymmetry, Kruskal---Wallis test was used. When

compar-ingproportionsbetweengroups,Pearson’schi-squaredtest

andprevalence ratiowitha 95%confidence intervalwere

applied. The association between nutritional assessment

methodswasassessedbyKendallcoefficient.Theagreement

betweenthemethodswasevaluatedbyKappacoefficient.

Thesignificancelevelwassetat5%(p<0.05).

Results

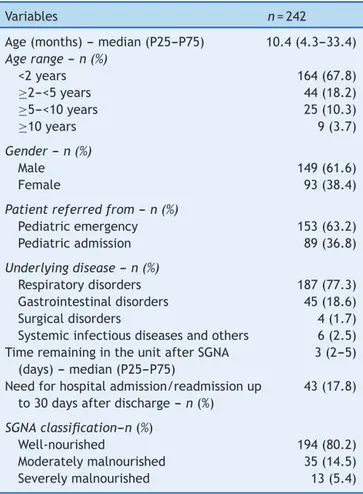

The sample comprised 242 patients, with a median age of approximately 10 months (25th---75th percentiles: 4.3---33.4),withminimumofonemonthandamaximumof 162months.Theagerangeyoungerthan2years predomi-nated(67.8%),aswellasthemalegender(61.6%).Sample characterizationisshowninTable1.

Table1 Characterizationofthestudysample.

Variables n=242

Age(months)---median(P25---P75) 10.4(4.3---33.4)

Agerange---n(%)

<2years 164(67.8)

≥2---<5years 44(18.2)

≥5---<10years 25(10.3)

≥10years 9(3.7)

Gender---n(%)

Male 149(61.6)

Female 93(38.4)

Patientreferredfrom---n(%)

Pediatricemergency 153(63.2)

Pediatricadmission 89(36.8)

Underlyingdisease---n(%)

Respiratorydisorders 187(77.3) Gastrointestinaldisorders 45(18.6)

Surgicaldisorders 4(1.7)

Systemicinfectiousdiseasesandothers 6(2.5) TimeremainingintheunitafterSGNA

(days)---median(P25---P75)

3(2---5)

Needforhospitaladmission/readmissionup to30daysafterdischarge---n(%)

43(17.8)

SGNAclassification---n(%)

Well-nourished 194(80.2)

Moderatelymalnourished 35(14.5)

Severelymalnourished 13(5.4)

SGNA,SubjectiveGlobalNutritionalAssessment.

Table2 AssociationbetweenSubjectiveGlobalNutritionalAssessment(SGNA)dataandobjectiveanthropometric measure-ments(z-score).

Variables N SGNA p rKendall

Well-nourished Moderatelymalnourished Severelymalnourished

Mean±SD Mean±SD Mean±SD

W/H---zscore 208 0.72±1.40b −0.82±0.97a −1.04±2.66a <0.001 −0.36 W/A---zscore 233 0.31±1.13b −1.57±0.51a −2.23±0.76a <0.001 −0.53 H/A---zscore 242 −0.16±1.23c −1.49±0.98b −2.43±2.04a <0.001 −0.37 BMI/A---zscore 242 0.57±1.43b −0.98±1.14a −0.77±2.87a <0.001 −0.34 AC/A---zscore 198 0.45±1.12b −0.65±1.06a −0.83±1.76a <0.001 −0.32 TSF/A---zscore 198 0.63±1.25b −0.23±1.06ab −0.52±1.24a <0.001 −0.23 SSF/A---zscore 198 0.82±1.38b −0.25±1.20a −0.29±1.34a <0.001 −0.25

SGNA,subjectiveglobalnutritionalassessment;W/H,weightforheight;W/A,weightforage;H/A,heightforage;BMI/A,bodymass indexforage;AC/A,upperarmcircumferenceforage;TSF/A,tricepsskinfoldthicknessforage;SSF/A,subscapularskinfoldthickness forage.

Datawereexpressedasmean±standarddeviation.

a,bEquallettersdonotdifferbyTukeytestatthe5%significancelevel.

Of the totalsample, 153patients were treated at the EmergencyPediatric Unit (63.2%) and89 at theInpatient Pediatric Unit (36.8%). The most frequent diagnosis was respiratorydisease(77.3%),followedbygastrointestinal dis-ease(18.6%).

Psychometricproperties

Concurrentvalidity

Nutritionalstatus, as determinedby the SGNA, was com-pared with anthropometric measurements. According to the SGNA, 194 patients (80.2%) were classified as well-nourished,35patients(14.5%)asmoderatelymalnourished, and13patients(5.4%)asseverelymalnourished.

Overall,therewasasignificantdifferencebetweenthe groups;thegroupclassifiedaswell-nourishedshowed signi-ficantlyhighervaluesthantheother two(moderatelyand severelymalnourished)inallnutritionalassessment meth-ods(objectiveandsubjective). However,amongthe mod-eratelyandseverelymalnourished,thedifferencewasonly significantinrelationtoheight/ageratio(Table2).Kendall

coefficients disclosed the weak-to-regular associations

betweenthenutritionalassessmentmethods.Theratiothat

showedthegreatestassociationwithSGNAwasweight/age.

Predictivevalidity

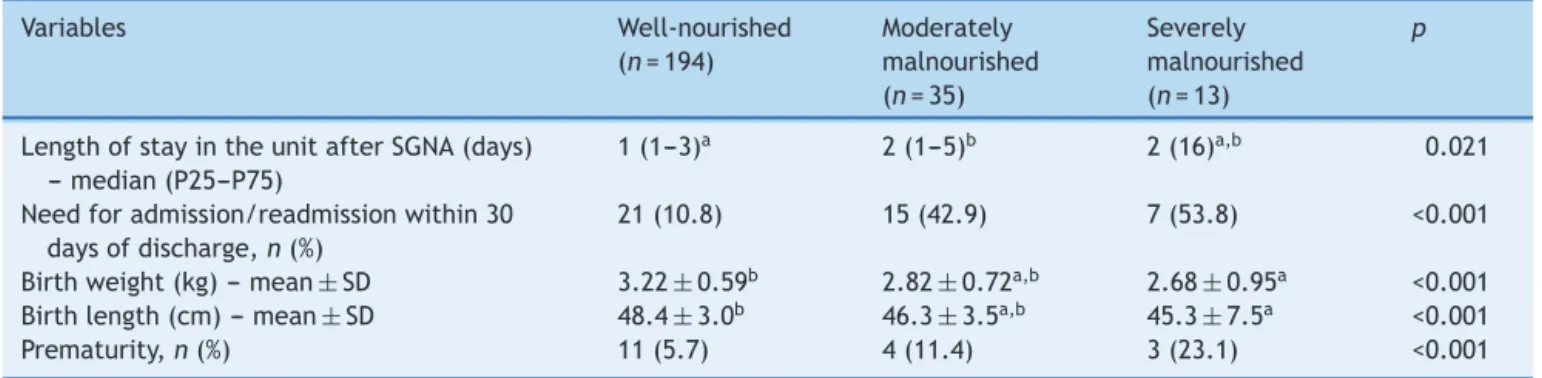

The need for hospital admission/readmission occurred in 43 cases (17.8%). The median (25th---75th percentiles) of timeofadmission/readmissionwastwodays.The probabil-ityofadmission/readmissionwasapproximatelyfourtimes higherinmoderatelymalnourishedpatientswhencompared to normal weight ones (PR=3.96; 95% CI: 2.27---6.91). In severelymalnourishedpatients,theprobabilityofhospital admission/readmissionwasapproximatelyfivetimesgreater when comparedtonormal weightones(PR=4.97; 95%CI: 2.61---9.48).

Nutritional status classified by SGNA was associated withall assessed outcomes (Table3). Patientsconsidered

by SGNA as severely malnourished had lower weight and

length at birth than the group of patients considered

well nourished (p<0.05). Moreover,the need for hospital

admission/readmission and prematurity increasedwithan

increasingdegreeofmalnutrition(p<0.001).

Table3 AssociationbetweenSubjectiveGlobalNutritionalAssessment(SGNA)dataandoutcomes.

Variables Well-nourished

(n=194)

Moderately malnourished (n=35)

Severely malnourished (n=13)

p

LengthofstayintheunitafterSGNA(days) ---median(P25---P75)

1(1---3)a 2(1---5)b 2(16)a,b 0.021

Needforadmission/readmissionwithin30 daysofdischarge,n(%)

21(10.8) 15(42.9) 7(53.8) <0.001

Birthweight(kg)---mean±SD 3.22±0.59b 2.82±0.72a,b 2.68±0.95a <0.001 Birthlength(cm)---mean±SD 48.4±3.0b 46.3±3.5a,b 45.3±7.5a <0.001

Prematurity,n(%) 11(5.7) 4(11.4) 3(23.1) <0.001

SGNA,SubjectiveGlobalNutritionalAssessment.

Datawereexpressedasmean±standarddeviation,median(P25---P75),orabsolutenumber(%)asindicated.

Interobserverreliability

There was good interobserver agreement (kappa=0.74; p<0.001), and the percentage of well-nourished, moder-atelymalnourished,andseverelymalnourishedindividuals weresimilarforthetwoobservers.Thecorrelationoccurred in56of61cases(92%).

Discussion

Subjective global assessment has been widely used, asit isaneasy-to-performmethodthatdoesnotrequire expen-siveresourcesandcanbeperformedby professionalsthat comprisethemultidisciplinaryteam.14

This study translated and validated the SGNA for the

Brazilian pediatric population, through the following

psy-chometricproperties:concurrentandpredictivevalidityand

interobserverreliability.

Concurrent validityassessesthecorrelation of thetool

withanothermeasure(thegoldstandard)usedtomeasure

whatisbeingassessed,bothappliedsimultaneously.24This

studyfoundasignificantassociationbetweenSGNAand

com-monlyusedanthropometricmeasures,asreportedby

Brazil-ianstudiesinvolvingadultswithdifferentpathologies.3,25---27

Theresultswerealsosimilartothosefoundintheoriginal

studybySeekerandJeejeebhoy7involvingchildren

under-goingsmallsurgicalprocedures.However,itis noteworthy

thattheagreementobserved betweenthemethods, SGNA

andanthropometricmeasures, wasweak-to-regularinthis

study(p<0.001).

The predictive validity includes future predictions,

regardingthequalitywithwhichatoolcanpredictafuture

criterion.24 The nutritional status evaluatedby SGNA was

associated with all assessed outcomes (need for hospital

admission/readmission within 30 days after hospital

dis-charge, length of hospital stay after SGNA, weight and

length at birth,and prematurity)(p<0.05). An increasing

degreeofmalnutritionaccordingtotheSGNAclassification

wasassociatedwithincreasedcomplications.Studiesusing

subjectiveassessmentasanevaluationmethodofthe

nutri-tionalstatusof hospitalizedpatientshave alsoshown this

power.7,26,28

Theinterobserverreliabilityevaluatesthe

reproducibil-ity of a tool through its application by two or more

observers.24 In this study, there was good reliability

(Kappa=0.74;p<0.001),higherthantheonefoundin the

originalstudybySeckerandJeejeebhoy.7

Becausethisisasubjectivemethod,theSGNA

diagnos-ticaccuracydependsonobserver’sexperienceandtraining,

whichisitsmaindisadvantage.However,studiescarriedout

with adultsalso attained a level of agreementsimilar to

thatobtainedinthisstudy.Inanearlystudyonnutritional

status assessment,Baker etal.15 showedgood agreement

between their evaluators (Kappa=0.72), as well as

Det-sky et al.29 when they standardized the clinical method,

creatingasubjective nutritionalassessmentquestionnaire

(Kappa=0.78).Inmorerecentstudies,aweak-to-moderate

concordancewasobservedbetweentheevaluators.Secker

and Jeejeebhoy,7 studyingsurgical pediatric patients in a

hospitalinCanada,obtainedKappa=0.28.Beguettoetal.,30

studyingadultpatientsadmittedtoauniversitygeneral

hos-pitalinPortoAlegre,RS,foundKappa=0.46.

The evaluation of the psychometric properties of the

SGNAinthisstudyshowedthetoolhasgoodinterobserver

reliability,in additiontohavingconfirmed theconcurrent

andpredictivevalidityofthequestionnaires.Itsapplication

inBrazilianchildrenandadolescentsandin different

clin-icalsituationsfromthatoftheoriginalstudyshowedgood

results.Afterthetranslationand studyofthe

psychomet-ricpropertiesoftheSGNA,thetoolshowedtobereliable

andvalidforassessingthenutritionalstatusofchildrenand

adolescents.

In this study,hospital stay showed noassociation with

theSGNA,unlikewhatotherstudiesreported.7,9,25 A

possi-bleexplanationmaybe duetothe factthat theselected

patients had acute diseases and were admitted through

thePediatricEmergencyUnit. In thestudy by Seckerand

Jeejeebhoy,7patientswerefromtheSurgicalInpatient

Pedi-atricUnit.

Alimitationofthisstudywasthedifficultyofperforming

biochemicalteststoconfirm thediagnosisofthepatient’s

nutritionalstatus.However,thepositiveaspectofthestudy

wasthedemonstration ofthehigh sensitivityoftheSGNA

questionnairefor nutritionalrisk andmalnutrition

diagno-sis.The fact that it considers the clinical and functional

alterations, which can lead the patient to a situation of

protein,energy,andimmunecompetenceloss,favoredthe

immediatediagnosisofnutritionalriskandmalnutrition.

SGNAvalidationfortheBrazilianpediatricpopulationcan

beastimulusfortheutilization ofthismethodas

system-aticassessment in pediatric services, in different clinical

situations. This can be performed as soon asthe patient

arrivesatthehospital,facilitatingtheidentificationofthose

whomaybeatnutritionalrisk,sothatthemostappropriate

nutritionalinterventioncanbeperformed.

Themethodologyusedandthecarefultranslationprocess

allowfor the conclusionthat SGNA isa valid andreliable

instrumentfor theassessment of thenutritional statusof

Brazilianpediatricpatients.

SGNAisausefuldiagnostictoolforassessingnutritional

status,withsimilarefficacytoanthropometricparameters,

regardlessoftheclinicalstatusofpatients.Thisstudy

vali-datedtheSGNAquestionnaireinthissampleofhospitalized

pediatricpatients,allowingitsuseforclinicalapplications

andforresearchpurposesintheBrazilianpopulation.

Funding

ThestudyreceivedsupportfromFIPE,Researchand Gradu-ateStudy Group,Hospital deClinicasdePortoAlegreand Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tec-nológico(CNPq).

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

Appendix

A.

Supplementary

data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jped. 2015.03.005.

References

1.RamosCV,DumithSC,CésarJA.Prevalenceand factors asso-ciatedwithstuntingand excessweightin childrenaged 0---5 years from the Braziliansemi-arid region.J Pediatr (Rio J). 2015;91:175---82.

2.JoostenKF,HulstJM.Malnutritioninpediatrichospitalpatients: currentissues.Nutrition.2011;27:133---7.

3.RaslanM,GonzalesMC,DiasMC,Paes-BarbosaFC,Cecconello I,WaitzbergDL.Applicabilityofnutritionalscreeningmethods inhospitalizedpatients.RevNutr.2008;21:553---61.

4.Rocha GA,RochaEJ, Martins CV. Theeffects of hospitaliza-tion on thenutritional status ofchildren. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2006;82:70---4.

5.Hendricks KM,Duggan C,Gallagher L, CarlinAC,Richardson DS, Collier SB, et al. Malnutrition in hospitalized pedi-atricpatients:currentprevalence.ArchPediatrAdolescMed. 1995;149:1118---22.

6.PawellekI,DokoupilK,KoletzkoB.Prevalenceofmalnutrition inpaediatrichospitalpatients.ClinNutr.2008;27:72---6. 7.SeckerDJ,JeejeebhoyKN.SubjectiveGlobalNutritional

Assess-mentforchildren.AmJClinNutr.2007;85:1083---9.

8.Mehta NM, Corkins MR,Lyman B, Malone A, Goday PS, Car-neyLN,etal.Definingpediatricmalnutrition:aparadigmshift toward etiology-related definitions. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr.2013;37:460---81.

9.SarniRO,CarvalhoMdeF,doMonteCM,AlbuquerqueZP,Souza FI.Anthropometricevaluation,riskfactorsformalnutrition,and nutritionaltherapyforchildreninteachinghospitalsinBrazil. JPediatr(RioJ).2009;85:223---8.

10.KyleUG,GentonL,PichardC.Hospitallengthofstayand nutri-tionalstatus.CurrOpinClinNutrMetabCare.2005;8:397---402. 11.ChimaCS.Dietmanualstopracticemanuals:theevolutionof

nutritioncare.NLNConvPap.2007;22:89---100.

12.Barbosa-SilvaMC,BarrosAJ.Indicationsandlimitationsofthe use of subjective global assessment in clinical practice: an update.CurrOpinClinNutrMetabCare.2006;9:263---9. 13.Barbosa-Silva MC, de Barros AJ. Subjective global

assess-ment: Part 2. Review of its adaptations and utilization in different clinical specialties. Arq Gastroenterol. 2002;39: 248---52.

14.Seres DS. Surrogate nutrition markers, malnutrition, and adequacy of nutrition support. NLN Conv Pap. 2005;20: 308---13.

15.Organizac¸ãoMundialdaSaúde.Classificac¸ãoEstatística Inter-nacionaldeDoenc¸aseProblemasRelacionadosàSaúde/CID-10 10arevisão.In:Traduc¸ãodoCentrocolaboradordaOMSpara

a Classificac¸ãode Doenc¸as emPortuguês.5thed.São Paulo: EDUSP;1997.

16.Baker JP, Detsky AS, Wesson DE, Wolman SL, Stewart S, WhitewellJ, et al. Nutritional assessment: a comparison of clinicaljudgmentandobjectivemeasurements.NEnglJMed. 1982;306:969---72.

17.AlvesMM,CarvalhoPR,WagnerMB,CastoldiA,BeckerMM,Silva CC.Cross-validationoftheChildren’sandInfants’Postoperative PainScaleinBrazilianchildren.PainPract.2008;8:171---6. 18.Orientac¸õesparaacoletaeanálisededadosantropométricos

emservic¸osdesaúde:NormaTécnicadoSistemadeVigilância AlimentareNutricional---SISVAN.Brasília:MinistériodaSaúde, Secretaria de Atenc¸ão à Saúde, Departamento de Atenc¸ão Básica;2011.

19.Secker DJ, Jeejeebhoy KN. How to perform Subjective Global Nutritionalassessment inchildren. J AcadNutrDiet. 2012;112:424---31.

20.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Child Growth Standards:length/height-for-age,weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: methodsanddevelopment.Geneva:WorldHealthOrganization; 2006.

21.World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Child Growth Stan-dards:methodsanddevelopment:headcircumference-for-age, armcircumference-for-age, tricepsskinfold-for-ageand sub-scapularskinfold-for-age.Geneva:WorldHealthOrganization; 2007.

22.FrisanchoA. Anthropometric standards:aninteractive nutri-tionalreferenceofbodysizeandbodycompositionforchildren andadults. 2nded.Ann Arbor:UniversityofMichiganPress; 2008.

23.FentonTR,KimJH.Asystematicreviewandmeta-analysisto revisetheFentongrowthchartforpreterminfants.BMCPediatr. 2013;13:59.

24.BlackerD,EndicottJ.Psychometricproperties:conceptsof reli-abilityandvalidity.In:RushAJ,editor.Handbookofpsychiatric measures.Washington, DC:AmericanPsychiatric Association; 2000.p.7---14.

25.BaccaroF,MorenoJB,BorlenghiC,AquinoL,ArmestoG,Plaza G,etal.Subjectiveglobalassessmentintheclinicalsetting. JPENJParenterEnteralNutr.2007;31:406---9.

26.YamautiAK,OchiaiME,BifulcoPS,deAraújoMA,AlonsoRR, RibeiroRH,et al.Subjectiveglobalassessmentofnutritional statusincardiacpatients.ArqBrasCardiol.2006;87:772---7. 27.Coppini LZ, Waitzberg DL, Ferrini MT, da Silva ML,

Gama-Rodrigues J, Ciosak SL. Comparison of thesubjective global nutrition assessment×objective nutrition evaluation. Rev AssocMedBras.1995;41:6---10.

28.Detsky AS, Baker JP, O’Rourke K, Johnston N, Whitwell J, Mendelson RA, et al. Predicting nutrition-associated complicationsforpatientsundergoinggastrointestinalsurgery. JPENJParenterEnteralNutr.1987;11:440---6.