www.jped.com.br

REVIEW

ARTICLE

Education

in

children’s

sleep

hygiene:

which

approaches

are

effective?

A

systematic

review

夽

,

夽夽

Camila

S.E.

Halal

a,b,

Magda

L.

Nunes

b,∗aGrupoHospitalarConceic¸ão,PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil

bFaculdadedeMedicina,PontifíciaUniversidadeCatólicadoRioGrandedoSul(PUC-RS),PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil

Received7May2014;accepted14May2014 Availableonline25June2014

KEYWORDS

Sleephygiene; Sleepeducation; School-aged; Child

Abstract

Aim: Toanalyze the interventionsaimed atthe practiceofsleephygiene, aswell astheir

applicabilityandeffectivenessintheclinicalscenario,sothattheymaybeusedbypediatricians

andfamilyphysiciansforparentaladvice.

Sourceofdata: AsearchofthePubMeddatabasewasperformedusingthefollowing

descrip-tors:sleephygieneORsleepeducationANDchildrenorschool-aged.IntheLILACSandSciELO

databases,thedescriptorsinPortuguesewere:higieneEsono,educac¸ãoEsono,educac¸ãoE

sonoEcrianc¸as,ehigieneEsonoEinfância,withnolimitationsofthepublicationperiod.

Summaryofthefindings: Intotal,tenarticleswerereviewed,inwhichthemainobjectives

weretoanalyzetheeffectivenessofbehavioralapproachesandsleephygienetechniqueson

children’ssleepqualityandparents’qualityoflife.Thetechniquesusedwereoneormoreofthe

following:positiveroutines;controlledcomfortingandgradualextinctionorsleepremodeling;

aswellaswrittendiariestomonitorchildren’ssleeppatterns.Alloftheapproachesyielded

positiveresults.

Conclusions: Althoughbehavioralapproachestopediatricsleephygieneareeasytoapplyand

adhereto,therehavebeenveryfewstudiesevaluatingtheeffectivenessoftheavailable

tech-niques.Thisreviewdemonstratedthatthesemethodsareeffectiveinprovidingsleephygiene

forchildren,thusreflectingonparents’improvedqualityoflife.Itisofutmostimportancethat

pediatriciansandfamilyphysiciansareawareofsuchmethodsinordertoadequatelyadvise

patientsandtheirfamilies.

©2014SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

夽 Pleasecitethisarticleas:HalalCS,NunesML.Educationinchildren’ssleephygiene:whichapproachesareeffective?Asystematic

review.JPediatr(RioJ).2014;90:449---56.

夽夽

StudyconductedatPontifíciaUniversidadeCatólicadoRioGrandedoSul,PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:nunes@pucrs.br,camilahalal.neuro@hotmail.com(M.L.Nunes). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2014.05.001

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Higienedosono; Educac¸ãodosono; Infância;

Crianc¸a

Educac¸ãoemhigienedosononainfância:quaisabordagenssãoefetivas?Uma revisãosistemáticadaliteratura

Resumo

Objetivo: Avaliarasintervenc¸õesvisandopráticasdehigienedosonoemcrianc¸as,sua

aplicabil-idadeeefetividadenapráticaclínica,paraqueasmesmaspossamserutilizadasnaorientac¸ão

dospaispelospediatrasemédicosdefamília.

Fontedosdados: Foirealizadabusca nabasededadosdaPubmedutilizando osdescritores

sleephygieneORsleepeducationANDchildorschool-aged,enasbasesLilacseScielo,com

asseguintespalavras-chave:higieneEsono,educac¸ãoEsono,educac¸ãoEsonoEcrianc¸as,e

higieneEsonoEinfância,nãotendosidolimitadooperíododebusca.

Síntesedosdados: Foram revisados10 artigos cujosobjetivos eram analisar efetividade de

abordagenscomportamentaisedetécnicasdehigienedosonosobreaqualidadedosonodas

crianc¸asenaqualidadedevidadospais.Foramutilizadasumaoumaisdasseguintestécnicas:

rotinaspositivas,checagemmínimacomextinc¸ãosistemáticaeextinc¸ãogradativaou

remod-elamentodosono,bemcomodiáriosdopadrãodesono.Todasasabordagensapresentaram

resultadospositivos.

Conclusões: Apesar de a abordagem comportamental no manejo do sono na faixa etária

pediátrica ser de simples execuc¸ão e adesão, existem poucos estudos na literatura que

avaliaramsuaefetividade.Osestudosrevisadosevidenciaramqueestasmedidassãoefetivas

nahigieneerefletememmelhorianaqualidadedevidadospais.Édefundamental

importân-ciaospediatrasemédicosdefamíliaconheceremestasabordagens,paraquepossamoferecer

orientac¸õesadequadasaseuspacientes.

©2014SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Todososdireitos

reservados.

Introduction

Theprevalenceof sleepdisordersishigh inchildhoodand mayaffectupto30% ofschool-agechildren.1,2 These

dis-orders are important due to the effects they can have

not only on the child, but also on their families and

society.3 Thus, a child with chronic sleep disorders may

have learning and memory consolidation impairment at

school,irritabilityandmoodmodulation alterations,

diffi-cultysustainingattention,andbehavioralalterationssuch

asaggression,hyperactivity,orimpulsivity.4---7Furthermore,

thechronicsleepdeficit lowersthethresholdfor

acciden-talinjuryandpromotesmetabolicchangesthat,inthelong

term,cancauseother conditions,suchasoverweightand

itsconsequences.8,9

Pediatriciansandfamilyphysiciansplayakeyrolein

pro-motingquality of sleepin children.10,11 For this purpose,

theyneedtohave knowledge ofmethods of sleepquality

promotion,ofphysiologyaspectsandage-dependentsleep

modifications,andoftheimportanceofgood-qualitysleep

inchildhood.12 Arecentstudydemonstratedthat,although

96%of Americanpediatricians consideritto betheir role

toadvise parents about sleephygiene methods, only 18%

reportedhavingreceivedformaltrainingonthesubject.10

Moreover,intheUnitedStates,theSleepinAmericaPoll,

conductedin 2004,includingapproximately1,500families

ofchildrenupto10yearsold,demonstratedthatonly13%of

pediatriciansaskedparentsaboutpossiblesleepdisorders.13

Asurveyconductedinpediatricsresidencyprogramsinthe

UnitedStates,Canada,Japan,India,Vietnam,SouthKorea,

Singapore,andIndonesiaobservedthatthemeantimespent

in sleep education at the institutions in those countries

wastwohoursduringthetrainingperiod,andthata

quar-terofthereportedprogramsofferednoinstructiononthe

subject.14

Sleep disorders are divided into eight different

cate-gories,whichincludeinsomnia,sleepdisorderedbreathing,

hypersomnia of central origin, circadian rhythm

dis-orders, parasomnias sleep-related movement disorders,

unresolved issues and isolated symptoms (which include

snoring, somniloquy, and benign myoclonus), and other

sleep disorders.15 The latter category includes sleep

dis-orders considered to be physiological or environmental.16

Theenvironmentaldisorders,oftenofbehavioralorigin,can

be prevented if properly managed throughsleep hygiene

measures.17

Objective

The objective of thisarticle wasto performa systematic reviewof interventionsaimingat sleephygiene, andtheir applicabilityandeffectivenessinpediatricclinicalpractice, sothattheycanbeusedinparentalguidance.

Methods

withcomorbidities (hospitalizationduring the study, neu-rologicalor respiratory diseases, behavioralor psychiatric disorders).

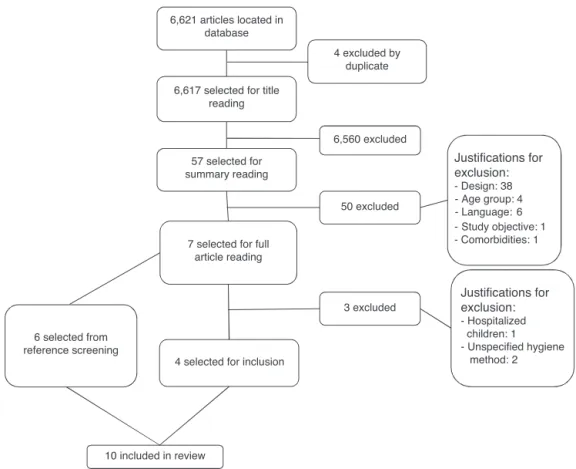

Studies of childrenwithdiagnosis of parasomnias were alsoexcludedfromthisanalysis,aswellasthoseinwhich the sleep hygiene method was not properly specified in themethodssection.OnlystudiespublishedinPortuguese, English, and Spanish were reviewed. The search totaled 6,621articles,ofwhichfourwereexcludedasduplicates.Of theremaining6,617,afterreadingthetitles,57were con-sideredpossiblyrelevantandhadtheirabstractsreviewed. Ofthese, 50were excludedfor not meetingthe inclusion criteria,andsevenwereselectedtobereadasfull texts. Ofthese,fourwereconsideredrelevantforthisstudy.18---21

Thesamesearch,butwithdescriptorsinPortuguese,was

conducted in the LILACS and SciELO databases. The

key-wordsusedwerehigieneEsono,educac¸ãoEsono,educac¸ão

EsonoEcrianc¸as,ehigieneEsonoEinfância.IntheLILACS

database,tworeferenceswerefound,neitherofwhichmet

thescopeofthisreview.IntheSciELOdatabase,the

descrip-torshigieneEsonoresultedin20articles,noneofwhichmet

thecriteriaforinclusioninthisstudy.Inthissamedatabase,

thedescriptorseducac¸ãoEsonoEcrianc¸asresultedinfive

articles,noneofwhichmetthescopeofthisreview.

The analysis of the studies and their references also

offeredthepossibilityofaccesstootherpublications,and

thusatotalofsixnewreferencesweresoughtandincluded

in this review.22---27 Fig. 1 shows the process of search,

selection, andexclusionof articlespresent in thecurrent

literature.

Definitions

The diagnosis of sleep disorders requires the presence of specificcriteria,whichmustbepresentforaspecificperiod oftimeandhavenegativeconsequencesonthechildand/or parents.1 Thus, mild or moderate symptoms arenot

con-sidereddisorders,althoughtheycancausesomedegreeof

impairment.28

The mean latency to sleep onset is usually about 19

minutesin children up to2 years of age, and 17minutes

from the age of 3 until the beginning of adolescence.29

In children, insomnia, defined as difficulty initiating or

maintaining sleep and comprising a number of

sub-classifications,usuallyfallsunderthediagnosisofbehavioral

insomnia.30 That, in turn, is divided between 1)

sleep-onsetassociation typeand2) limit-setting type,or mixed

form.

Themost commonsubtype,‘‘limit-setting type’’,

com-prisesthe attempttopostpone goingto sleepor refusing

todoso,characterizedbycrying, refusingtostay inbed,

orrequestsforfood,drink,orthereadingofstories.Inthis

context,itiscustomarytoidentifyparentswithinconsistent

routinesthattendtogiveintotheirchildren’srequests.31

Inthe‘‘sleep-onsetassociation’’subtype,certainbehaviors

needtoberepeatedateverywakingepisodeforthechildto

resumesleep.Thus,achildthatassociatessleeponsetwith

thepresenceofoneorbothparents,food,orbeingrocked

tosleep,whenawakeningduringthenight-evenwith

nor-malawakeningsexpectedfortheiragegroup-needstohave

theritualrepeatedtoresumesleep.32

6,621 articles located in database

6,617 selected for title reading

57 selected for summary reading

7 selected for full article reading

4 selected for inclusion

4 excluded by duplicate

6,560 excluded

50 excluded

Justifications for exclusion:

- Design: 38 - Age group: 4 - Language: 6

-Study objective:1 - Comorbidities: 1

3 excluded

Justifications for exclusion:

- Hospitalized children: 1 - Unspecified hygiene method: 2 6 selected from

reference screening

10 included in review

Parents′ perception of their child having poor quality sleepisdirectlyrelatedtothenumberofnightwakingsand tohowdemandingthechildistoinitiatesleepatbedtime andretake sleep afternight wakings.29,33 A recent

analy-sisofdatafromBrazilianbirthcohortfound,at12months,

aprevalenceof nocturnalawakeningsof 64.4%in thetwo

weeksprecedingthestudy,with56.5%ofthechildren

wak-ingupeverynight,andmostofthematleasttwotimeseach

night.34

Theterm‘‘sleephygiene’’includeschangesinsleep

envi-ronment,aswellasengagingthechildandtheirparentson

routineandpracticesthatencouragesleepofgoodquality

andsufficientduration.Italsoincludesthepracticeof

sooth-ingactivitiesduringwakefulnessaimingtopropitiatesleep

onset.11Themostusualpracticesarehavingconsistent

bed-timeandwake-uptimeforboththenocturnalanddaytime

sleep(amongchildrenattheagegroupwherenapsare

con-sideredphysiological),establishingtheappropriateplaceto

initiatesleep,and avoiding environmental andbehavioral

associationswithsleeponset(beingrockedtosleep,parents

layingonthechild’sbeduntilsleeponset,nursingtosleep,

watchingTVinbed,ordrinkingbeveragesrichincaffeine

closetobedtime).17

Childrenwhoneedbehavioralassociationstofallasleep,

uponawakeningduringthenight,willneedtheseresources

againinordertoresumesleep.1Thepassivepresenceofa

parent,however,appearstobepositiveatsomeagegroups,

aswellastheuseofthechild’sownresources,suchasusing

apacifierorthumb-suckingandsleepingwithatransitional

object.35

Methodsofsleephygienepromotion

The most studied methods are discussed below. These strategiesappeartoworkbetterinchildrenaged2yearsand older,whenarewardsystemcanbeused.2However,some

studieshaveattemptedtoadvisepregnantwomenor

par-entsofinfantsinordertopromoteproblemprevention.1,33

Extinction:Parentsshouldputthechildinbedata

pre-specifiedtimeandignorethechilduntilacertaintimeon

thefollowing morning,while monitoringforthepossibility

ofinjury.Themethodisbasedoneliminatingtheactsthat

reinforcecertainbehaviors(suchascryingonawakening),

aimingat their extinction over time.36 The greatest

diffi-cultyinimplementingthis strategyis theparents’lack of

consistencyandtheparentalanxietythatisgenerated.Asa

result,somedefendthestrategyofextinctioninthe

pres-enceofparents,suchthatparentsremainintheroombut

donotrespondtothechild’sbehavior.2,36

Gradualextinction:Inspiteofcomprisingdifferent

tech-niques,the gradual extinction method usually consists of

ignoringthedemandsofthechildforspecifictimeperiods;

these periods are usually determined by the child’s age

andtemperamentandtheparents’discretioninrelationto

howlong theytoleratetheirchild’scrying. Parentsshould

calmthechildfor shortperiods,whichusuallyrangefrom

15secondstooneminute. Thetechniqueaimstopromote

thechild’scapacitytoself-sootheandreturntosleep,

with-outundesirableassociationsorparentalinterference.1,2,36

When assessing 79 children with a mean age of 10.2

months (3-24 months) whose parents were instructed to

implementthegradualextinctiontechniqueduring

noctur-nal sleep,Skuladottir etal.observedthatthe durationof

nocturnal sleep increasedfrom 10.27hours to10.57hours

(p<0.001) afterthe intervention, aswell asreducing the

frequency ofnocturnal awakenings(from4.57to1.57per

night,p<0.001).18

Eckerbergconductedastudy toassesswhether

recom-mendations provided only in written form tothe parents

of children treated at a clinic for sleep disorders would

work aswell as clinical follow-up, which hadbeen

previ-ouslyadvocated.19Guidancetoparentsofchildrenincluded

in the study followed the gradualextinction method, the

same provided by the physician during routine

consulta-tions. Atotal of39 children between 4and 30months of

ageparticipated inthestudy,divided intoan intervention

group(writteninformationsentby email,withoutcontact

withtheclinician) and acontrol group(information given

bytheclinician).Aftertheintervention,childrenfromboth

groups fell asleepfaster (p<0.001) and earlier (p<0.01),

which amounted to 30minutes earlier after a one-month

intervention.

In both groups, there was also a significant reduction

in nocturnal awakenings (from 4.6 to 4.2 awakenings in

thecontrolandfrom3.3to2.8in theinterventiongroup,

p<0.001)inthetwoweeksfollowingtheintervention.The

probability of resume sleep on their own also increased

aftertheintervention(2.1-foldinthecontroland2.0-fold

in the intervention group,p<0.001). After threemonths,

thisdecrease continuedin bothgroups, and therewasan

increaseinthedurationofnocturnalsleep(by59minutesin

thecontrolandby72minutesintheinterventiongroup)and

adecreaseintimeofwakefulnessduringthenight(from82

to18minutes,p<0.001),withnodifferencesbetweenthe

groups.

InanAustraliancase-controlstudycarriedoutbyHiscock

&Wake,146childrenbetween7and9monthsofagewere

recruited from an outpatient setting.22 The intervention

group received specialized guidance on the physiology of

sleepandtheapplicationofthegradualextinctionmethod,

whereasthecontrolgroupreceivedanewsletterabout

nor-mal sleeppatterns at theage range of6-12 months. Two

monthslater,childrenintheinterventiongrouphadresolved

more sleep problems than those in the control group

(p=0.005), andthe remainingproblems wereless intense

in the intervention group. Maternal depressive symptoms

decreasedinbothgroupsaftertwomonths,butdecreased

moresignificantly intheinterventiongroup (p=0.02),the

groupwhosemothersalsoreportedthattheirownsleepwas

ofbetterquality(p=0.02)attheendofthefollow-up.

Aiming to compare the effectiveness of the gradual

extinction and extinction methods, and of these in

rela-tiontono sleephygienemethod,ReidMJ etal. analyzed

43children aged16to48months(14extinction,13

grad-ualextinction,and16controls)priortointervention,andat

21daysandtwomonthsafterintervention.23Theyobserved

that families allocated to the extinction group had more

difficulty adheringtothe methodduringthe secondweek

inrelationtothegradualextinctiongroup(interruptingthe

interventiononaverage3.4timeseachweek,comparedto

1.1timesintheothergroup,p=0.02).Duringtheremaining

time,adherenceremainedhighandsimilarinbothgroups

The intervention groups also had better assessments

regarding qualityat both themoment of sleeponset and

sleepmaintenance,whencomparedtothecontrolgroup.In

thesubscaleregarding qualityofsleepin theCBCL(Child

Behavior Checklist), both intervention groups also scored

betterinrelationtothecontrolgroup,andsimilarlytoeach

other.Twomonthslater,anewevaluationshowedthatthe

benefitsremained inthe groups thatunderwent

interven-tions.

Minimalcheckingwithsystematic extinction:Similarto

theextinctionmethod,butthechildcanbecheckedevery5

to10minutes,andtheparentcancomfortthechildquickly

whennecessary,arrangingthecovers,andmakingsurethat

therearenocomplications.2

Adachi etal. analyzed 99 children taken for childcare

consultation at 4 months of age, randomly dividing them

between intervention and control groups.20 The

interven-tion consisted of information about positive routines for

initiating sleep, appropriate and inappropriate behaviors

to resume sleep at night, and the method of minimal

checking with systematic extinction. At the end of the

study, the intervention group had a greater decrease in

the rates of behaviorslisted as‘‘inadequate’’. The

char-acteristicof‘‘givingfoodoradiaperchangeimmediately’’

decreasedfrom66.7%to36.4%(p=0.001),andthe

charac-teristicdescribedas‘‘holdingandcomfortingimmediately’’

decreased from 22.7% to10.6% (p=0.021). In the control

group,thenumberof nocturnal awakeningsincreased

sig-nificantlyfrom53%to66.7%(p=0.022),asdidthenumber

ofawakeningswithcrying(from8.1%to19.4%,p=0.065).

AninterventionconductedbyHalletal.included39

fam-iliesofinfantsaged6to12months,whoseparentssought

helpthroughatelephoneansweringservice forparentsof

infantswithdifficultysleeping.21Theaimofthestudywasto

analyzetheimprovementintheparents’qualityoflife,and

at theend of theintervention, a significant improvement

intheparents’qualityofsleepwasobserved,aswellasof

symptomsofdepressedmoodandfatigue.Theco-sleeping

ratesalsodecreasedsignificantly(from70%practicingthem

before the intervention to 74% not practicing them after

theintervention,p<0.001),withnochangeinthepractice

ofbreastfeeding.

Positive routines: This methodconsistsof the

develop-ment of routines preceding bedtime, comprisingpeaceful

andpleasurable activities.37 Anotherstrategy thatcan be

used is delaying the time to go to bed to ensure that,

whenlyingdown,thechildwillfallasleepquickly,untilthis

habit offalling asleepquicklyis consolidated. After that,

startanticipatingbedtimeby15to30minutesonsuccessive

nights until the time considered appropriate is achieved.

Thechildshouldnotsleepduringtheday,exceptattheage

groupsinwhichdaytimesleepisphysiological.2,36

Positiveroutinesareoftenusedincombinationwithother

methods of sleep hygiene. Adachi et al. included

behav-ioral recommendationsin theirintervention group.At the

end of the intervention, they found that the practice of

positiveroutinescharacterizedby‘‘playingandstimulating

duringtheday’’(p=0.003),‘‘establishingaplacetosleep’’

(p=0.008),and‘‘establishingatimetabletosleepandwake

up’’(p=0.007)hadincreasedsignificantly.20

Mindelletal.performedastudyincludingchildrenintwo

groups(7-18monthsand18-36months),inwhicharoutine

precedingsleepwasimplemented,consistingofabath

fol-lowedbymassageandquietactivities,withatimeperiod

betweenthebathandturningoffthelightsof30minutes.24

Theroutinesignificantlyreducedproblembehaviorsinboth

groups,withdecreasedsleeplatencyandthenumberand

durationof nocturnalawakenings(p<0.001). Themothers

inthegroupofchildrenagedupto18monthsshowed

reduc-tioninsymptomsofstress,depression,anger,fatigue,lack

ofstamina,andconfusion(p<0.001)and,inthegroupolder

than18months,therewasanimprovementinthesymptoms

ofstress,anger,fatigue,andconfusion(p<0.001).

This study had a long-term follow up, in which 65%

of participants in the group aged up to 18 months were

randomized into three groups: one received instructions

exclusively via the internet, another received

instruc-tions via the internet in addition to those described

in the previous study, and a third group was used as

control.25 After one year, the improvements observed in

the twogroups that received the interventions regarding

sleeplatency, difficulty falling asleep, number and

dura-tionof nocturnal awakenings,periodof continuous sleep,

and maternal confidence in relation to her child’s sleep

management persisted (p<0.001). After three weeks of

intervention, the qualityof maternal sleep improved

sig-nificantly(p<0.001);afteroneyear,however,itdecreased

back to levels close to those at the start of the

intervention.

Aiming tocompare the effectiveness between positive

routinesandgradualextinctioninreducingtempertantrums

with bouts of anger at bedtime, Adams and Rickert

fol-lowed, for six weeks, two groups of children targeted

for each intervention compared to a control group, in

a total of 36 children (12 per group) aged between 18

and48months.26 The children inthe groups submittedto

any of the interventions had significantly fewer bouts of

anger, which were of shorter duration than the controls

(p<0.05 and p<0.001, respectively). There was no

sig-nificant difference in response between the intervention

groups, although children in the group submittedto

pos-itive routines showed faster favorable responses. Parents

inthegroupallocatedtoimplementpositiveroutinesalso

scoredbetterontheMaritalAdjustmentScaleattheendof

theintervention,whichwasvalidatedforthatpopulation,

andinvestigatestheperceptionthatthecouplehasoftheir

relationship.38

Programmed awakening: It consists in waking up the

childatnight,between15and30minutesbeforetheusual

timeofspontaneousawakening,andafterthat,comforting

hertoreturntosleep.Thenumber ofprogrammed

awak-eningsshould varywiththe usual number of spontaneous

awakenings.Overtime,ittendstoextinguishspontaneous

awakenings,andtheprocessofreducingscheduled

awaken-ingsbegins,resultinginincreasedsleepconsolidation.1,2,36

Rickert&Johnsoncomparedthemethodsofprogrammed

awakeningandsystematicextinctionwithacontrolgroupin

33childrenwitha meanageof 20months(6-54months),

randomly allocating them into three groups of 11

chil-dren (programmed awakening, systematic extinction, and

acontrolgroup).27Theinterventionlastedeightweeks,and

parentswerere-contactedthreeandsixweekslater.

Chil-drenwhoexperiencedtheinterventionsshowed,attheend

Halal

CS,

Nunes

ML

Table1 Studiesreviewed,authors,agerangeofstudy,numberofparticipants,objectives,typeofintervention,andoutcomes.

Author/yearof

publication

Agerange n Mainobjective Sleephygienemethod Results

Adachietal.,20

2009

4months Intervention:99 Control:95

-Decreaseofinappropriatebehavior, nighttimeawakenings,andarousals withcrying

-Positiveroutines -Minimalcheckingwith systematicextinction

-Decreaseofinappropriatebehaviors

-Preventionofincreasednocturnalawakenings withage

Halletal.,21

2006

6to12 months

39 -Assessmentofparents’qualityof lifeafterimprovementofthechild’s sleepquality

-Minimalcheckingwith systematicextinction

-Improvementofsleepqualityanddepressed moodsymptomsofparents

-Decreaseinco-sleeping Rickert&

Johnson,27

1988

6-54 months

33(11ineach interventiongroup, 11incontrolgroup)

-Evaluationofthereductioninthe numberofnocturnalawakenings

-Programmedawakening -Systematicextinction -Control

-Lowernumberofnighttimeawakeningsin bothgroupsthatunderwentinterventions

Mindelletal.,24

2009

7to18 months 18to36 months

206(7-18m) 199(18-36m)

-Changesinmaternalmoodafter improvedsleepqualityofthechild

-Positiveroutines -Decreasedsleeplatencyinchildren -Decreaseinthedurationofnocturnal awakenings

-Decreaseindepressivesymptomsinmothers Mindelletal.,25

2011

18to48 months

171 -Changeinsleepqualityofchildand mother

-Changeinmaternalself-confidence

-Positiveroutines -Decreaseinsleeplatency,difficultyfalling asleep,numberanddurationofnocturnal awakenings

-Maternalself-confidenceimprovement -Temporaryimprovementofthequalityof maternalsleep

Skuladottir etal.,182005

3to24 months

79 -Changesinthenocturnalsleep patternwithimproveddaytimesleep pattern

-Positiveroutinesfordaytime sleep

-Gradualextinctionfor nighttimesleep

-Remodelingfordaytimesleep

-Increaseinnocturnalsleep -Decreaseinnocturnalawakenings

Adams& Rickert,26

1989

18and48 months

36(12ineach interventiongroup; 12incontrolgroup)

-Effectonthenumberoftemper tantrums

-Positiveroutines -Gradualextinction

-Lowernumberoftempertantrumsand shorterepisodesinbothinterventiongroups -Bestscoreintheparents’group

positiveroutinesintheMaritalAdjustment Scale

Eckerberg,19

2002

4to30 months

39 -Effectivenessofwritteninformation oververbalinstructionsbythe physician

-Gradualextinction -Decreaseinsleeplatencyinbothgroups -Decreaseofawakeningsinbothgroups -Increasedchancetogobacktosleepontheir owninbothgroups

Hiscock& Wake,222002

7to9 months

Intervention:75 Control:71 (total146)

-Effectivenessoftheadvicegivenby thephysicianinrelationtowritten adviceonsleepqualityofthechild andmaternaldepressivesymptoms

-Gradualextinction -Fewersleepproblemsintheintervention group

-Decreaseinmaternaldepressivesymptomsin theinterventiongroup

Reidetal.,23

1999

16to48 months

43(14inextinction group,13ingradual extinctiongroup, and16controls)

-Comparisonoftheeffectivenessof methodsofsleephygiene

-Extinction -Gradualextinction

although this decrease occurred faster in the group sub-mittedtotheextinctionmethod.Thisdifferenceremained statisticallysignificantduringthereassessments.

Sleepremodeling:Consistsofnotallowingnapstooccur attimesthatcandisruptnocturnalsleeponset,which com-prisesfourhoursbeforebedtimeinchildrenatanagerange thatallowstwonapsperday,andsixhoursbeforebedtime inchildrenwhousuallyhaveonenapaday.18

ThestudydevelopedbySkuladottiretal.usedthis

tech-nique for daytime naps.18 As demonstrated above, they

observedpositiveresultsregardingthedurationofnocturnal

sleep.

Table1summarizes thestudiesincluded inthepresent

review by author, age group andsample size, objectives,

typeofintervention,andmainresults.

Discussion

The number of studies available in the literature on interventions targeting sleep hygiene in children without comorbid conditions is scarce.18---27 It is noteworthy that

no Brazilian studies were found in this search. A recent

cross-sectionalstudyperformedin theUnitedStates,with

children aged5 to6years froma low-incomecommunity

consistingpredominantlyofLatinofamilies,observeda

four-fold higher prevalence of sleep alterations than normally

expectedatthisage,suggestingthatunfavorable

socioeco-nomicconditionsmaycontributetopoorsleepquality.39

This finding indicates the potential importance of this

typeofstudyandsubsequentinterventionsintheBrazilian

population,consideringthatthesleepqualityimprovement

amongchildrenofdifferentagerangesandsocioeconomic

levelscould also contribute tothe improvement of other

indicesofqualityoflife.

Some studies observed that groups of children

receiv-ing no intervention also obtained improvements in sleep

quality indices at the reassessments. One possible

expla-nation is the existence of an association between neural

maturationandphysiological circadianmechanisms,which

inthemselvesactasasleepregulator,improvingsleep

qual-ityovertime.1However,itisnoteworthythatchildrenwho

receivedinterventionsconsistentlyshowedmoresignificant

improvements regardingindicesof sleepquality.This fact

suggeststheimportanceoftheexternalenvironmentonthe

sleepmaturationprocess.

Informationprovidedonlyinwriting(brochures,

newslet-ters)canbeequallyeffective.19 Thisispossiblyduetothe

factthesecanbeconsultedasoftenasparentsdeem

nec-essary, and asdoubts arise in the implementation of the

techniques.

Theinterventionsperformedinthereviewedstudiesare

simpleandeffective,andrepresentsecondaryeducational

measures for parentsthat donotimply additionalcostto

themortothehealthsystem,becausetheybasicallyconsist

ofrecommendations.Itispossiblethattheseinterventions

wouldactuallyimplycostsavingstothesystem,aswellto

advisedparents,whosechildrensleepbetter,andthuswould

probablyhavealowerchanceofseekingspecializedcare,in

additiontohavingbetterperformanceintheirprofessional

activities.Thefavorableresultsofalltheinterventionsthat

objectively sought to analyzemood and qualityof life of

parentscorroboratethishypothesis.

Thereviewedstudiesaddressedabroadagerange,

vary-ingfrom3monthsto4years,mostlycomprisingchildrenin

theirfirstyearoflife. Theimportanceof thisinformation

liesinthefactthatinterventionsinchildrenyoungerthan

2yearsalsoappeartobeeffective,allowingearlychanges

andpreventingchildren’sexposuretolongperiodsofpoor

sleep.

The role of the health professional who works with

children is to know the physiologyof sleepand its

phys-iological maturation process. The inclusion of questions

aboutsleepqualityandpossiblesleepimpairmentfactorsin

theanamnesis,inadditiontoofferingsleephygiene

guide-linesregardingthepreventionortreatmentofpathological

behaviors,shouldbepartofeverypediatricvisit.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.MindellJA,KuhnB,LewinDS,MeltzerLJ,SadehA.Behavioral treatmentofbedtimeproblemsandnightwakingsininfantsand youngchildren.Sleep.2006;29:1263---76.

2.NunesML,CavalcanteV.Avaliac¸ãoclínicaemanejodainsônia empacientespediátricos.JPediatr(RioJ).2005;81:277---86. 3.Karraker KH, Young M. Night waking in 6-month-old infants

and maternal depressive symptoms. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2007;28:493---8.

4.HaleL,BergerLM,LeBourgeoisMK,Brooks-GunnJ.A longitu-dinalstudyofpreschoolers’language-basedbedtimeroutines, sleepduration,andwellbeing.JFamPsychol.2011;25:423---33. 5.Blunden SL, Chapman J, Rigney GA. Are sleep education programs successful? The case for improved and consistent researchefforts.SleepMedRev.2012;16:355---70.

6.QuachJ,GoldL, ArnupS,SiaK-L,WakeM,HiscockH.Sleep well-be well study: improving school transition by improv-ing child sleep: a translational randomisedtrial. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e004009.

7.Owens J.Classification and epidemiology ofchildhood sleep disorders.PrimCareClinOfficePract.2008;35:533---46. 8.Cappuccio FP, Taggart FM, Kandala NB, Currie A, Peile E,

Stranges S, et al.Meta-analyses ofshort sleep duration and obesityinchildrenandadults.Sleep.2008;31:619---26. 9.Blunden SL,ChervinRD.Sleep problemsare associated with

pooroutcomesinremedialteachingprogrammes:Apreliminary study.JPaedChildHealth.2008;44:237---42.

10.Faruqui F, Khubchandani J, Price JH, Bolyard D, Reddy R. Sleep disorders in children: a national assessment of pri-marycarepediatrician practicesandperceptions.Pediatrics. 2011;128:539---46.

11.Gruber R, Cassoff J, Knäuper B. Sleep health education in pediatriccommunitysettings:rationaleand practical sugges-tionsforincorporatinghealthysleepeducationintopediatric practice.PediatrClinNorthAm.2011;58:735---54.

12.MindellJA,MolineML,ZendellSM,BrownLW,FryJM. Pedia-triciansandsleepdisorders:trainingandpractice.Pediatrics. 1994;94:194---200.

13.NationalSleepFoundation.SleepinAmericaPoll.2004.[cited

on20Mar2014].Availablefrom:www.sleepfoundation.org

14.Mindell Ja, Bartle A, Ahn Y, Ramamurthy MB, Huong HTD, KohyamaJ,etal.Sleepeducationinpediatricresidency pro-grams:across-culturallook.BMCResNotes.2013;6:130. 15.Oliveiero B,NovelliL. Sleepdisordersinchildren. ClinEvid.

16.AmericanAcademyofSleepMedicine.International classifica-tionofsleepdisorders:diagnosticandcodingmanual.2nded.

Westchester:AmericanAcademyofSleepMedicine;2005. 17.Mindell JA, Meltzer LJ, Carskadon MA, Chervin RD.

Devel-opmental aspects of sleep hygiene: Findingsfrom the 2004 NationalSleepFoundationSleep inAmericaPoll.SleepMed. 2009;10:771---9.

18.Skuladottir A, Thome M, Ramel A. Improving dayand night sleepproblemsininfantsbychangingdaytimesleeprhythm: a single group before and after study. Int J Nurs Studies. 2005;42:843---50.

19.Eckerberg B. Treatment of sleep problems in families with smallchildren: iswritten informationenough?ActaPaediatr. 2002;91:952---9.

20.AdachiY,SatoC,NishinoN,OhryojiF,HayamaJ,YamagamiT.A briefparentaleducationforshapingsleephabitsin4-month-old infants.ClinMedRes.2009;7:85---92.

21.HallWA,ClausonM,CartyEM,JanssenPA,SaundersRA.Effects onparentsofaninterventiontoresolveinfantbehavioralsleep problems.PedNurs.2006;32:243---50.

22.HiscockH,WakeM.Randomisedcontrolledtrialofbehavioural infantsleepinterventiontoimproveinfantsleepandmaternal mood.BMJ.2002;324:1062---7.

23.Reid MJ, Walter AL, O’Leary SG. Treatment of young chil-dren’sbedtime refusaland nighttime wakings:a comparison of‘‘standard’’and graduatedignoringprocedures.JAbnorm ChildPsychol.1999;27:5---16.

24.MindellJA,TelofskiLS,WiegandB,KurtzES.Anightlybedtime routine:impactonsleepinyoungchildrenandmaternalmood. Sleep.2009;32:599---606.

25.MindellJA,DuMondCE,SadehA,TelofskiLS,KulkarniN,GunnE. Long-termefficacyofaninternet-basedinterventionforinfant andtoddlersleepdisturbances:oneyearfollow-up.JClinSleep Med.2011;7:507---11.

26.AdamsLA,RickertVI.Reducingbedtimetantrums:comparison betweenpositiveroutinesandgraduatedextinction.Pediatrics. 1989;84:756---61.

27.Rickert VI, Johnson CM. Reducing nocturnal awakening and crying episodes in infantsand young children: a comparison

betweenscheduledawakeningsandsystematicignoring. Pedi-atrics.1988;81:203---12.

28.ThorpyMJ.Classificationofsleepdisorders.Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9:687---701.

29.Galland BC, Taylor BJ, Elder DE, Herbison P. Normal sleep patternsininfantsandchildren:Asystematicreviewof obser-vationalstudies.SleepMedRev.2012;16:213---22.

30.MorgenthalerTI,OwensJ, AlessiC,BoehleckeB, BrownTM, ColemanJ,etal.Practiceparametersforbehavioraltreatment ofbedtimeproblems andnight wakingsininfantsandyoung children.Sleep.2006;29:1277---81.

31.WardTM,RankinS,LeeKA.Caringforchildrenwithsleep prob-lems.JPediatrNurs.2007;22:283---95.

32.AnuntasereeW,Mo-suwanL,VasiknanonteP,KuasirikulS, Ma-a-leeA,ChoprapawanC.NightwakinginThaiinfantsat3months ofage:associationbetweenparentalpracticesandinfantsleep. SleepMed.2008;9:564---71.

33.CookF,BayerJ, LeHN,MensahF,Cann W, Hiscock H.Baby business: a randomised controlled trial of a universal par-entingprogram that aims to prevent early infantsleep and cryproblemsandassociatedparentaldepression.BMCPediatr. 2012;12:13.

34.SantosIS,MotaDM,MatijasevichA.Epidemiologyofco-sleeping andnighttimewakingat12monthsinabirthcohort.JPediatr (RioJ).2008;84:114---22.

35.Moore M, Meltzer LJ, Mindell JA. Bedtime problems and night wakings in children. Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 2008;35:569---81.

36.KuhnBR,ElliottAJ.Treatmentefficacyinbehavioralpediatric sleepmedicine.JPsychosomRes.2003;54:587---97.

37.GallandBC,MitchellEA.Helpingchildrensleep.ArchDisChild. 2010;95:850---3.

38.SpanierGB.Themeasurementofmaritalquality.JourSexMarit Ther.1979;5:288---300.