REVISTA

PAULISTA

DE

PEDIATRIA

www.rpped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Physical

activity

and

screen

time

in

children

and

adolescents

in

a

medium

size

town

in

the

South

of

Brazil

João

Paulo

de

Aguiar

Greca

a,∗,

Diego

Augusto

Santos

Silva

b,

Mathias

Roberto

Loch

caBrunelUniversityLondon,Uxbridge,GreaterLondon,UnitedKingdom bUniversidadeFederaldeSantaCatarina(UFSC),Florianópolis,SC,Brazil cUniversidadeEstadualdeLondrina(UEL),Londrina,PR,Brazil

Received27June2015;accepted5November2015

Availableonline29January2016

KEYWORDS

Sedentarylifestyles; Socioeconomic factors;

Leisureactivities; Television; Obesity

Abstract

Objective: Toanalyzetheassociationsbetweensexandagewithbehaviourrelatedtophysical activitypracticeandsedentarybehaviourinchildrenandadolescents.

Methods: Across-sectionalstudywith480(236boys)subjectsenrolledinapublicschoolinthe cityofLondrina,inthesouthofBrazil,aged8---17years.Measuresofphysicalactivity,sports practiceandscreentimeswereobtainedusingthePhysical ActivityQuestionnairefor Older Children.TheMann---WhitneyUtestwasusedtocomparevariablesbetweenboysandgirls.The ChisquaredtestwasusedforcategoricalanalysisandPoissonregressionwasusedtoidentify prevalence.

Results: Girls(69.6%;PR=1.05[0.99---1.12])spentmore timewith sedentarybehaviourthan boys(62.2%). Boys(80%; PR=0.95[0.92---0.98])weremore physicallyactivethangirls(91%). Olderstudentsaged13---17showedahigherprevalenceofphysicalinactivity(91.4%;PR=1.06 [1.02---1.10])andtimespentwithsedentarybehaviourof≥2h/day(71.8%;PR=0.91[0.85---0.97])

whencomparedtoyoungerpeersaged8---12(78.7and58.5%,respectively).

Conclusions: The prevalenceofphysicalinactivity washigher ingirls. Olderstudents spent morescreentimeincomparisontoyoungerstudents.

©2016SociedadedePediatriadeSãoPaulo.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBYlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:joao.deaguiargreca@brunel.ac.uk(J.P.Greca).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rppede.2016.01.001

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Sedentarismo; Fatores

socioeconômicos; Atividadesdelazer; Televisão;

Obesidade

AtividadefísicaetempodetelaemjovensdeumacidadedemédioportedoSul doBrasil

Resumo

Objetivo: Analisaraassociac¸ãodosexoeidadecomcomportamentosrelacionadosàprática deatividadesfísicasesedentarismoemcrianc¸aseadolescentes.

Métodos: Estudotransversalcom480(236sexomasculino)estudantesdeumaescolapública dacidadedeLondrina,Paraná,Brasil,comidadeentre8e17anos.Asmedidasdeatividade física,práticadeesportesequantidadedecomportamentossedentáriosforamobtidas medi-anteaplicac¸ãodoPhysicalActivityQuestionnaireforOlderChildren.OTestedeMann---Whitney Ufoiutilizadoparacompararvariáveisderapazesemoc¸as.OTestedeQui-Quadradofoiusado paravariáveiscategóricaseaRegressãodePoissonparaidentificarprevalências.

Resultados: Moc¸as (69,6%; RP=1.05 [0.99---1.12])dedicaram mais tempo ao comportamento sedentárioquandocomparadasarapazes(62,2%).Rapazes(80%;RP=0.95[0.92---0.98]) apresen-tarammaioresníveisdeatividadefísicaquandocomparadosamoc¸as(91%).Estudantesmais velhoscomidadeentre13---17anos(91,4%;RP=1.06[1.02---1.10])apresentarammaior prevalên-ciadeinatividadefísicaecomportamentosedentáriode≥2h/dia(71,8%;RP=0.91[0.85---0.97])

quandocomparadosaestudantescomidadeentre8e12anos(78,7e58,5%,respectivamente).

Conclusões: Aprevalênciadeinatividadefísicafoisuperiorentreasmoc¸as.Estudantesmais velhosdespenderammaistempoemtelaquandocomparadosaestudantesmaisnovos. ©2016SociedadedePediatriadeSãoPaulo.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Esteéumartigo OpenAccesssobalicençaCCBY(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.pt).

Introduction

The current literature reports that higher levelsof phys-ical activity can reduce the risk of premature all-cause mortality, and also supports the dose---response relation-shipbetweenphysicalinactivityandchronicconditions,i.e.

cardiovasculardisease,stroke,hypertension,coloncancer, breast cancer, type 2 diabetes and osteoporosis.1 Stud-ieshave shownthat increasedsedentary behaviours,such as television viewing, video game playing, playing com-putergames,and/orelectronicgameplaying,areassociated withunfavourablebodycomposition,decreasedfitness, low-ered scores for self-esteem and pro-social behaviour and decreasedacademicachievementinschool-agedchildren.2 Lowlevelsofphysical activityin childhoodand adoles-cence have been reported worldwide, with a proportion of 80.3% doing fewer than 60min of physical activity of moderate tovigorous intensity per day.3 A study describ-ingadolescents’physicalactivitylevelswithdatafrom32 countries concluded that the majority of adolescents do not meet current recommendations of physical activity.4 In Brazil,high levelsof physicalinactivity in children and adolescentswerereportedinthe southern5 andnortheast regions.6

Sedentarybehaviourisrelatedtoanunhealthylifestyle earlyinchildhoodandadolescence.Watchingtelevisionfor morethantwohours,forinstance,increasesthechancesof overweightandobesityasreductionsinsedentarybehaviour arelinkedtobetterbodycomposition.2Recentpublications haveshownthatsedentarybehaviourinyoungpeople, espe-cially inthe formofTV viewing,is associatedwithaless healthfuldiet,suchaslessfruitandvegetableconsumption andagreaterconsumptionofenergy-densesnacksand bev-eragescontainingsugar.7,8Moreover,behavioursestablished

inschool-agechildrentendtocontinueintoadulthood9and studiesthatincludethispopulationhavebeensuggested.1

Someprevious Brazilian studiesinvolving physical inac-tivity and sedentary behaviour focused on investigating adolescents5,6 but didnot stratify subgroups i.e. age and gender comparisons as recommendedelsewhere.7 Studies thataimedat other variables amongchildrenand adoles-centsalso didnotpresent datadifferentiating theage of girlsand boys.10 These stratificationswould givea better understandingofdiseasemechanismsduringchildhoodand adolescenceandhelpthemaintenanceofahealthylifestyle fromchildhoodintoadulthood.Thus,theaimofthisstudy wastoanalyzetheassociationsbetweensexandagewith behaviourrelatedtophysicalactivitypracticeandsedentary behaviourinchildrenandadolescents.

Method

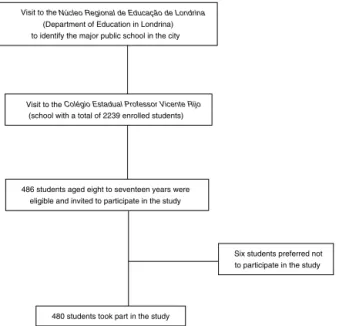

Thisstudyhadacross-sectionaldesign.Datacollectiontook placeduringthesecondsemesterof2011inthecityof Lond-rina,thefourthlargestcityinthesouthernregionofBrazil. ThecityofLondrinahasapopulationsizeof543,003 inha-bitants,withaHumanDevelopmentIndexof0.778.Itisthe secondlargestcityinthestateofParanaafterthecapital, Curitiba.The city has a stableeconomyand according to itsGrossDomesticProductitisrankedastherichestcityin thenorthofParana.11ThisstudywasapprovedbytheEthics Committeeon Researchwith HumanSubjects of the Uni-versidadeEstadual de Londrina (CAAE 0089.0.268.000-11) (Fig.1).

Visit to the Núcleo Regional de Educação de Londrina (Department of Education in Londrina) to identify the major public school in the city

Visit to the Colégio Estadual Professor Vicente Rijo (school with a total of 2239 enrolled students)

486 students aged eight to seventeen years were eligible and invited to participate in the study

Six students preferred not to participate in the study

480 students took part in the study

Figure1 Flowchartexplainingtheselectionprocessofthe sample.

54.000m2,islocatedinthecentralzoneofthecityandisthe

mainschoolinthemunicipalarea.Astheschoolislocatedin thecentralzoneofthecityandithasstudentsfrom differ-entmunicipalregions,itwaspossibletofindalargevariety ofstudentsfromdifferentsocioeconomicstatus.Theschool hada total amount of 2239 students. A total of 486 stu-dentsenrolledfrom3rdto8thgrades, allresidentsofthe citywherethestudytookplace.Thesestudentswere eligi-bleandinvitedtoparticipateinthisstudy;inclusioncriteria forjoiningthestudywere:(1)anageofeightto17years, (2)studentswhomanifestedinterestinparticipatingafter invitation,and (3)studentsandparents whoreturnedthe questionnaireandthesignedconsentformwithinformation aboutthestudy.Nopoweranalyseswerecompletedforthe samplesize.

The physical activity score was measured using the validated12 Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Chil-dren(PAQ-C)13translatedintothePortugueselanguageand adapted by Silva and Malina14 to applyto the context of Brazilian students.Thus, noreproducibility assessment of thePAQ-Cwasmadeinthisstudy.Thestudentsfilledoutthe questionnaireinsidetheirclassroomunderthesupervisionof researcherspreviouslytrainedforitsapplication.The PAQ-Cinvestigatestheamountofmoderateandintensephysical activitycarried outin the sevendaysprior tocompleting thequestionnaire.Itiscomposedof 13questionson play-ingsportsandgamesandphysical activities atschooland duringleisure time,includingweekends,duringtheschool year.Answersweregivenona5pointLikert-typescale ran-gingfrom‘verysedentary’to‘veryactive’.Scores2,3,and4 representedthecategories‘sedentary’,‘moderatelyactive’ and‘active’,respectively.Therefore,fromthefinalscore, itwaspossibletoclassifythestudentsasphysicallyactive orinsufficiently active,accordingtoCrocker andBailey.13 Thosewithscores≥3wereconsideredactiveandthosewith scores<3wereconsideredinsufficientlyactive.13,14

Timespentwatchingtelevision,usingthecomputerand playingvideogamesusewasassessedanddefinedasscreen

time.2 According to the current recommendations based on self-reports and direct measurements,2 a screen time of ≥2h/day wascategorized ashigh sedentary behaviour, whereas a screen time <2h/day was categorized as low sedentarybehaviour.

Theevaluationofbodymassandheightofboysandgirls wasconductedinsidetheclassroomonthesamedayofthe questionnaire’s application. The body mass was assessed using a weight scale with a variation range of 0.1---150kg (Britânia, Curitiba,Brazil).Beforeweightassessment, the subjectsremovedtheirshoesandthen stoodpositionedin the centre of the weighing scale platform wearing light clothes.Fortheheight,astadiometerwithaprecisionrange of0.1cm(Sanny,SãoBernardodoCampo,Brazil)wasused. Afterobtainingbodymassandheight,thebodymassindex (BMI)usingthespecificreferencevaluesforgenderandage proposedbyColeandLobstein15wascalculated.Each sub-jectwasclassifiedinaccordancewithhisorhernutritional status:eutrophic,overweightorobese.

After these procedures, students filled out another questionnaire16 created by the Brazilian Association of Research Companies for the assessment of the family’s economicstatus.Thequestionnairewasdevelopedin accor-dance with the life conditions of Brazilian families. The students’ families wereclassified into classes: A, B, C, D andEandthendividedintohigh/middle(classesAandB)or lowclass(classesC,DandE).

TheMann---WhitneyU testwasutilizedtocompare age variablesfrombothgendersandthechi-squaretestwasused forcategoricalanalysis.Poissonregressionwasusedto con-structamodelfortheobservedassociations.Toanalyzethe degree of the associationsbetween variables,prevalence ratiosandconfidenceintervalsof95%wereused.Allcasesof significance(p-value)lessthan5%wereconsidered statisti-callysignificant.Analyseswereperformedonthestatistical software SPSS (Statistical Packagefor the Social Sciences Inc.,Chicago,Illinois),version20.0.

Results

Atotalof480students,consistingof236boysand244girls agedeightto17participatedinthestudy.Sixstudentswere not abletojoin the study astheyrefused toparticipate,

i.e. due toshame of exposing their body weightor body typeduringtheanthropometrymeasurementsorduetothe factthattheirparentsdidnotreturnthequestionnaires.

Overall, the majority of the sample (boys=62.2%; girls=69.9%),spentmorethantwohours/daywithactivities relatedtoscreen,i.e.television,computeror videogames (PR=1.05 [0.99---1.12]).Theprevalence ofphysical inactiv-ity was also high (boys=80%; girls=91%) in both genders (PR=0.95 [0.92---0.98]). The students’ economic classes foundwere:A=8.4%,B=67.1%,C=20.2%,D=0.8%andE=34%.

Table 1 shows the descriptive analysis according to age, weight, height,BMI and physical activity levels according tothePAQ-C,andsedentarybehavioursandcomparisonsof both genders.According tothePAQ-C score,boysshowed higher levels of physical activity when compared to girls (boys=2.4;girls=2.0; p<0.001). Girlsspentmore hoursper daywithsedentarybehaviourthanboys(boys=2.4;girls=3.0;

Table1 Descriptiveanalysisofboysandgirls.

Girls Boys p-valuea

P25 Median P75 P25 Median P75

Age(years) 11.7 13.4 14.2 11.7 12.9 14.2 0.430 Weight(kg) 42.1 48.2 56.7 39.0 49.3 58.1 0.983 Height(cm) 150.5 157.0 161.6 147.9 158.2 166.5 0.181 Bodymassindex 17.6 19.2 22.8 17.0 19.3 22.2 0.262 PAQ-Cscore 1.6 2.0 2.4 2.0 2.4 2.8 <0.001

Sedentarybehaviour(h/day) 1.4 3.0 4.3 1.4 2.4 3.7 0.026 BodymassindexaccordingtoColeandLobstein(2012).Boldindicatesp<0.050.

a Mann---WhitneyUtest.

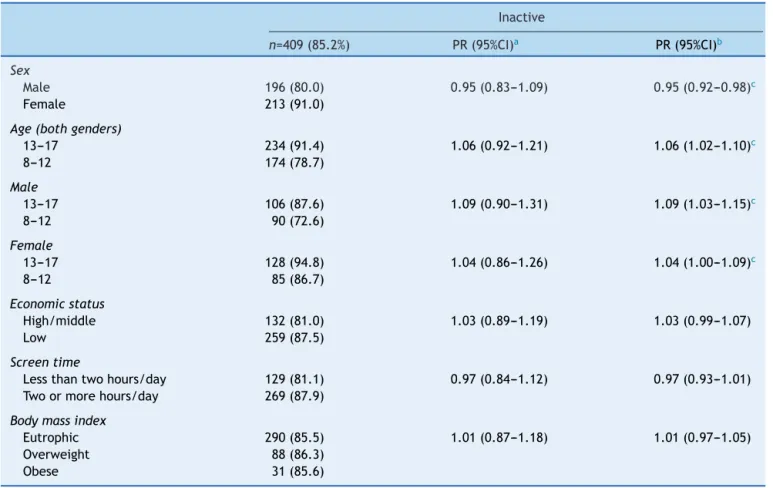

Table 2shows associationsbetweenlowlevelsof phys-ical activity and independent variables in students. High levelsofphysical inactivitywere foundin boysaged8---12 (72.6%), 13---17 years (87.6%; PR=1.09 [1.03---1.15]) and girls aged 8---12 (86.7%) and 13---17 years (94.8%; PR=1.04 [1.00---1.09]). After adjusted analysis, the prevalence of physical inactivity was found to be higher in girls (91%; PR=0.95[0.92---098]).Boys(87.6%;PR=1.09[1.03---1.15])and girls(94.8%;PR=1.04[1.00---1.09])aged13---17yearsshowed

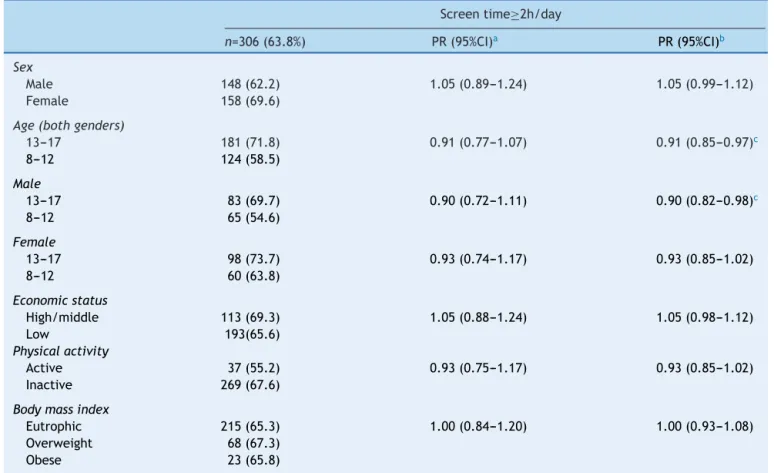

a higher prevalence of physical inactivity than younger peers. Table 3 shows associations between high screen time and independent variables in students. When ana-lyzing older boys and girls together, a higher prevalence of high screen time than their younger peers was found (71.8%;PR=0.91 [0.85---0.97]).When comparingolderboys to younger boys, the prevalence of older boys with high screentimewashigherthaninyoungerboys(69.7%;PR=0.90 [0.82---0.98]).

Table2 Associationbetweenlowlevelsofphysicalactivityandindependentvariablesinchildrenandadolescents. Inactive

n=409(85.2%) PR(95%CI)a PR(95%CI)b Sex

Male 196(80.0) 0.95(0.83---1.09) 0.95(0.92---0.98)c

Female 213(91.0)

Age(bothgenders)

13---17 234(91.4) 1.06(0.92---1.21) 1.06(1.02---1.10)c

8---12 174(78.7)

Male

13---17 106(87.6) 1.09(0.90---1.31) 1.09(1.03---1.15)c

8---12 90(72.6)

Female

13---17 128(94.8) 1.04(0.86---1.26) 1.04(1.00---1.09)c

8---12 85(86.7)

Economicstatus

High/middle 132(81.0) 1.03(0.89---1.19) 1.03(0.99---1.07)

Low 259(87.5)

Screentime

Lessthantwohours/day 129(81.1) 0.97(0.84---1.12) 0.97(0.93---1.01)

Twoormorehours/day 269(87.9)

Bodymassindex

Eutrophic 290(85.5) 1.01(0.87---1.18) 1.01(0.97---1.05)

Overweight 88(86.3)

Obese 31(85.6)

a Crudeanalysis.

Table3 Associationbetweenhighscreentimeandindependentvariablesinchildrenandadolescents. Screentime≥2h/day

n=306(63.8%) PR(95%CI)a PR(95%CI)b Sex

Male 148(62.2) 1.05(0.89---1.24) 1.05(0.99---1.12) Female 158(69.6)

Age(bothgenders)

13---17 181(71.8) 0.91(0.77---1.07) 0.91(0.85---0.97)c

8---12 124(58.5)

Male

13---17 83(69.7) 0.90(0.72---1.11) 0.90(0.82---0.98)c

8---12 65(54.6)

Female

13---17 98(73.7) 0.93(0.74---1.17) 0.93(0.85---1.02)

8---12 60(63.8)

Economicstatus

High/middle 113(69.3) 1.05(0.88---1.24) 1.05(0.98---1.12)

Low 193(65.6)

Physicalactivity

Active 37(55.2) 0.93(0.75---1.17) 0.93(0.85---1.02)

Inactive 269(67.6)

Bodymassindex

Eutrophic 215(65.3) 1.00(0.84---1.20) 1.00(0.93---1.08)

Overweight 68(67.3)

Obese 23(65.8)

aCrudeanalysis.

b Analysisadjustedbyallvariables,independentlyofp-valuefromcrudeanalysis. c p<0.050.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze the associations between sex and age with behaviour related to physical activity practiceand sedentary behaviour in children and adolescents. Comparing different gender groups in child-hoodandadolescence,girlsshowedlowerphysicalactivity levelsthanboys.Theresultsfromthisstudysupportprevious findings. Decelis et al.17 reported that a high percent-age of boys and girls are not meeting physical activity recommendations1andshowthatlevelsofphysicalactivity inchildhoodandadolescencestartdecreasingbefore adult-hood. Family plays an important role in physical activity practicein childhoodand adolescence.18 One explanation forboysengaginginmorephysicalactivitythangirlsisthat theyseemtohavemoresocialandfamilysupportfor prac-ticingphysical activity.19 There is stilla need topromote physicalactivityinchildhoodandadolescenceandthisdata canhelptodevelopinterventionsforthispopulation.These comparisonsdeliverinformationtotheliteratureas recom-mendedbeforeforfurtherstudies.7

Comparisonsmadewithgirlsfromdifferentage groups showedthatoldergirlsspendmorescreentimethanyounger girls. Consequences of high amounts of time spent with sedentary activities are expected in early childhood. A study of physical activity and obesity trends reported by

Sigmundováetal.7showedthat,overaperiodoftenyears, thetimespentwithsedentaryactivitiesincreasedandthe level ofphysical activity decreased in childhoodand ado-lescence.Cluster analysisconductedbyDeBourdeaudhuij et al.20 with children recruited from Hungary, Belgium, theNetherlands,GreeceandSwitzerlandshowedthatgirls spentmoretimebeingsedentarythanboys,similartoour findings. Sedentary activities of boys and girls are higher thanthecurrentrecommendations,2andprogrammes focus-ingonbothdecreasingsedentarybehaviourandincreasing physical activity areneeded, particularlyingirls.21 Lower levelsofphysicalactivityamongolderboysandgirlsmight beexplainedbythefact thatparentscanassociate lower academic achievement at school withthe time that they spendoutsidethehome,whichmightbeabarrierforolder boysandgirlstoengageinmorephysicalactivity.19

In this study, we found a higher prevalence of older male students spending more screen time and practicing lessphysicalactivitythanyoungerboys.Anexplanationfor thisdifferencefoundinourstudycouldbethatmanyolder boys have attributes that children still do not have, i.e.

The prevalence of sedentary behaviour found in the present studywashigh inboth genders,andthis corrobo-rates recentfindings ofa Brazilianstudy bySilva etal.,23 where the authors investigated the association between sports participation and sedentary behaviour and found thatthemajorityoftheadolescentsincludedintheir sam-ple had a high incidence of sedentary behaviour. Suchert etal.24 assessedeffectsofsedentarybehaviour,depressed affect, self-esteem, physical self-concept, general self-efficacyandphysicalactivity.Amonggirls,lowerscoresin self-esteemandgeneralself-efficacywereassociatedwith higherscreen-basedsedentarybehaviours.Melkeviketal.25 reportedthat the use ofelectronic media wasassociated withincreasedBMIz-scoresandhigheroddsofbeing over-weight in boys and girls who did not follow the physical activityguidelines.Recentresearch23foundanegative asso-ciation between sedentary behaviour and engagement in sportsinadolescents.

Ahighprevalenceofphysicalinactivitywasfoundin stu-dentswithhighscreentime.Severalstudiesanalyzedthese co-existentvariablesinthispopulation.Physicalactivityand more timespent withsedentary behaviour are relatedto academicskills.26Additionally,lowlevelsofphysicalactivity andhighlevelsofsedentarybehavioursincreasethechances of obesity in childhood.1,2 Obesity in childhood and ado-lescence is linkedto numerous chronic diseases in life. A BrazilianstudyconductedbyDutraetal.27reporteda preva-lenceofsedentarylifestyleofmorethan70%andthatscreen timewasinverselyassociated withphysical activity. Simi-larly,Ferrarietal.28foundahigherprevalenceofchildren meeting moderate tovigorous physical activity guidelines amongchildrenwhowatched ≤2h/dayof television.Still, insufficientphysicalactivityshouldnotberelatedto seden-tary behaviours as it is not directly linked to sedentary activitiesinvestigatedinthisstudy,i.e.televisionviewing.29 Evidenceshowsthattelevisionviewingandphysicalactivity inchildhoodandadolescencearenon-relatedconstructs,29 andpracticing morephysical activity does notnecessarily lowersedentarybehaviours.30Ourfindingsraisemajor con-cernsandtheycorroboratethehighprevalenceofbothrisk factors,highsedentarybehaviourandlowphysicalactivity, reportedelsewhere,indifferentregionsofBrazil.23,28

This study has limitations which must be taken into account:first, the method of investigation relies on self-reported questionnaires regarding physical activity and sedentary behaviours. There are advantages using these methods,i.e.fulldescriptionanddetailsaboutthephysical activityandtimespentwithsedentarybehaviour;however motionsensordeviceswoulddeliverbetterandmoreprecise information compared to the 7 day recall method. Sec-ondly, the cross-sectional design prevents the assessment ofcausality.Longitudinaldesignmightallowbetter under-standing,insteadof makingcomparisons betweenyounger andolderstudentsfromdifferentregionsofthetownand differentsocialclasses.Thesampleusedinthisstudyisnot representativeofallstudentsofthecity;howeveritis rep-resentativeofthemajorschoolinthecitywherethestudy tookplace. Additionally,theselectedschoolfor thisstudy hasstudentsfromallregionsofthecity.However,data col-lectionfromother cities would givea largersample size, andmakecomparisonsbetweensimilarstudiesfromother countriespossible.7

In conclusion, ourresults support evidence that physi-calactivitylevelsarelowerinolderstudentsthanyounger students.Additionally,olderstudentsspentmoretimewith sedentary activities than their youngerpeers. The preva-lenceofphysicalinactivitywashigheringirlsthaninboys. Older boys showed lower levels of physical activity and higheramountsofscreentimethanyoungerboys.

Funding

TheauthorJoãoPaulodeAguiarGrecawouldliketothank CAPES (Coordenac¸ão de Aperfeic¸oamento de Pessoal de NívelSuperior---Brasil)forthescholarshipprocessnumber BEX13281/13-5.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.JanssenI.Physicalactivityguidelinesforchildrenand youth. CanJPublicHealth.2007;98Suppl.2:S109---21.

2.TremblayMS,LeBlancAG,KhoME,SaundersTJ,LaroucheR, ColleyRC,etal.Systematicreviewofsedentarybehaviourand healthindicatorsinschool-agedchildrenandyouth.IntJBehav NutrPhysAct.2011;8:98.

3.HallalPC,AndersenLB,BullFC,GutholdR,HaskellW,Ekelund U,etal.Globalphysicalactivitylevels:surveillanceprogress, pitfalls,andprospects.Lancet.2012;380:247---57.

4.Kalman M,InchleyJ,Sigmundova D,IannottiRJ,Tynjälä JA, HamrikZ,etal.Seculartrendsinmoderate-to-vigorous physi-calactivityin32countriesfrom2002to2010:across-national perspective.EurJPublicHealth.2015;25Suppl.2:37---40. 5.GuilhermeFR,Molena-FernandesCA,GuilhermeVR,FáveroMT,

ReisEJ,RinaldiW.Physicalinactivityandanthropometric meas-uresinschoolchildrenfromParanavaí,Paraná,Brazil.RevPaul Pediatr.2015;33:50---5.

6.RiveraIR,SilvaMA,SilvaRD,OliveiraBA,CarvalhoAC.Physical inactivity,TV-watchinghoursandbodycompositioninchildren andadolescents.ArqBrasCardiol.2010;95:159---65.

7.SigmundováD,SigmundE,HamrikZ,KalmanM.Trendsof over-weightandobesity,physicalactivityandsedentarybehaviour in Czech schoolchildren: HBSC study. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24:210---5.

8.HobbsM,PearsonN,FosterPJ,BiddleSJ.Sedentarybehaviour anddietacrossthelifespan:anupdatedsystematicreview.Br JSportsMed.2015;49:1179---88.

9.FrancisSL,StancelMJ,Sernulka-GeorgeFD,BroffittB,LevySM, JanzKF.TrackingofTVandvideogamingduringchildhood:Iowa BoneDevelopmentStudy.IntJBehavNutrPhysAct.2011;8:100. 10.VasconcelosIQ,NetoAS,MascarenhasLP,BozzaR,UlbrichAZ, Campos W,et al.Fatoresderisco cardiovascularem adoles-centes com diferentes níveis de gasto energético. Arq Bras Cardiol.2008;91:227---33.

11.IBGE---InstitutoBrasileirodeGeografiaeEstatística[homepage ontheInternet].Cidades2014.Availablefrom:http://cidades. ibge.gov.br/xtras/perfil.php?lang=&codmun=411370&search= parana[cited22.06.15].

13.Crocker PR, Bailey DA. Measuring general levels of physical activity:preliminaryevidenceforthephysicalactivity question-naireforolderchildren.MedSciSportsExerc.1997;29:1344---9.

14.Silva RC, Malina RM. Level of physical activity in adoles-centsfromNiterói,RiodeJaneiro,Brazil.CadSaudePublica. 2000;16:1091---7.

15.ColeTJ,LobsteinT.Extendedinternational(IOTF)bodymass indexcut-offsforthinness,overweightandobesity. Pediatric Obesity.2012;7:284---94.

16.ABEP [homepage on the Internet]. Critério de Classificac¸ão EconômicaBrasil2011.Availablefrom:http://www.abep.org/ criterio-brasil[cited26.06.15].

17.DecelisA, JagoR, FoxKR.Physicalactivity,screentimeand obesity status ina nationally representative sample of Mal-teseyouthwithinternationalcomparisons.BMCPublicHealth. 2014;14:664.

18.FernandesRA,ReichertFF,MonteiroHL,FreitasJúniorIF, Car-dosoJR,RonqueER,etal.Characteristicsoffamilynucleusas correlatesofregularparticipationinsportsamongadolescents. IntJPublicHealth.2012;57:431---5.

19.Gonc¸alvesH,HallalPC,AmorimTC, AraújoCL,MenezesAM. Socioculturalfactorsandphysicalactivitylevelinearly adoles-cence.RevPanamSaludPublica.2007;22:246---53.

20.DeBourdeaudhuijI,Verloigne M,MaesL, VanLippevelde W, ChinapawMJ,TeVeldeSJ,etal.Associationsofphysicalactivity andsedentarytimewithweightandweightstatusamong10-to 12-year-oldboysandgirlsinEurope:aclusteranalysiswithin theENERGYproject.PediatrObes.2013;8:367---75.

21.VerloigneM,VanLippeveldeW,MaesL,YıldırımM,Chinapaw M,Manios Y,et al. Levelsof physicalactivity and sedentary timeamong10-to12-year-oldboysandgirlsacross5European countriesusingaccelerometers:anobservationalstudywithin theENERGY-project.IntJBehavNutrPhysAct.2012;9:34.

22.GuimarãesRM,RomanelliG. The inclusionof adolescentsof lowerclassesinthejobmarketthroughanong.Psicologiaem EstudoMaringá.2002;7:117---26.

23.SilvaDA,TremblayMS,Gonc¸alvesEC,SilvaRJ.Televisiontime amongBrazilianadolescents:correlatedfactors aredifferent betweenboysandgirls.SciWorldJ.2014;2014:794539.

24.SuchertV,HanewinkelR,IsenseeB,läuftStudyGroup. Seden-tary behavior, depressed affect, and indicators of mental well-beinginadolescence:doesthescreenonlymatterforgirls? JAdolesc.2015;42:50---8.

25.MelkevikO,HaugE,RasmussenM,FismenAS,WoldB, Borrac-cinoA,et al.Areassociationsbetweenelectronicmediause andBMIdifferentacrosslevelsofphysicalactivity?BMCPublic Health.2015;15:497.

26.HaapalaEA,PoikkeusAM,Kukkonen-HarjulaK,TompuriT,Lintu N,VäistöJ,etal.Associationsofphysicalactivityandsedentary behaviorwithacademicskills---afollow-upstudyamongprimary schoolchildren.PLoSOne.2014;9:e107031.

27.DutraGF,KaufmannCC,PrettoAD,AlbernazEP.Television view-inghabitsandtheirinfluenceonphysicalactivityandchildhood overweight.JPediatr(RioJ).2015;91:346---51.

28.FerrariGL,AraujoTL,OliveiraL,MatsudoV,MireE,Barreira TV,etal.Associationbetweentelevisionviewingandphysical activityin 10-yearoldBrazilianchildren. JPhys ActHealth. 2015;12:1401---8.

29.TaverasEM,FieldAE,BerkeyCS,Rifas-ShimanSL,FrazierAL, ColditzGA,etal.Longitudinalrelationshipbetweentelevision viewingandleisure-timephysicalactivityduringadolescence. Pediatrics.2007;119:e314---9.