Revista

de

Administração

http://rausp.usp.br/ RevistadeAdministração52(2017)59–69

Strategy

and

Business

Economics

Degree

of

equity

ownership

in

cross-border

acquisitions

of

Brazilian

firms

by

multinationals:

a

strategic

response

to

institutional

distance

Grau

de

propriedade

de

capital

nas

aquisi¸cões

de

empresas

brasileiras

por

multinacionais:

uma

resposta

estratégica

à

distância

institucional

Propiedad

de

capital

en

las

adquisiciones

de

empresas

brasile˜nas

por

multinacionales:

respuesta

estratégica

a

la

distancia

institucional

Manuel

Anibal

Silva

Portugal

Vasconcelos

Ferreira

a,b,∗,

Simone

César

da

Silva

Vicente

b,

Felipe

Mendes

Borini

c,

Martinho

Isnard

Ribeiro

de

Almeida

caInstitutoPolitécnicodeLeiria,Leiria,Portugal bUniversidadeNovedeJulho,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

cUniversidadedeSãoPaulo,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

Received22February2015;accepted15February2016 Availableonline10October2016

Abstract

Thisstudyanalyzeshowforeignmultinationalenterprisesrespondtouncertaintyintheircross-borderacquisitionsinemergingeconomiesand, specificallyinBrazil,giventheinstitutionaldifferencesthatseparatethehomeandhostcountries.Weanalyzehowinstitutionaldistanceimpacts multinationalenterprisesstrategyintakingapartialorfullownershipstakeintheirBrazilianacquisitions.Weproposethattheequitystakeisa strategicresponsetotheuncertaintyofoperatingininstitutionallydistantcountries.Inanstudybasedonsecondarydataof736acquisitionsbetween 2008and2012,wetestedstatisticallytherelationbetweenninedimensionsofinstitutionaldistanceandtheequitystakeacquired.Resultsshow differentiatedeffectsalbeitwithsignificantevidencethatgreatergeographicdistanceleadmultinationalenterprisestotakeapartialequitystake, whilefinancialandculturaldistanceleadstoafullacquisition.Thisstudyhastwocontributions:reinforcestheunderstandingoftheinstitutional challengesofenteringemergingeconomies,andputsforthhowfirms’strategiesmayincorporatestructuralsolutionsthatminimizerisksand investmentswhenfacinginstitutionaluncertainties.

©2016DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP.

PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBYlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Keywords:Institutionalenvironment;Institutionaldistance;Cross-borderacquisitions;Brazil;Uncertaintyreductionstrategy

Resumo

Esteartigoanalisaaformacomoasempresasmultinacionais(EMNs)estrangeirasrespondemàincertezanasaquisic¸õesdeempresasemeconomias emergentese,especificamente,noBrasil,faceàsdiferenc¸asinstitucionaisqueseparamospaísesdeorigemedestinodosinvestimentos.Analisamos comoadistânciainstitucionalimpactaaestratégiadasmultinacionaisestrangeirasnatomadadepropriedadeparcialoutotaldocapitalnasaquisic¸ões noBrasil.Propomosqueograudepropriedadeéumarespostaestratégicadiantedaincertezadeoperaremmercadosinstitucionalmentemais distantes.Numestudobaseadoemdadossecundáriosde736aquisic¸õesrealizadasentre2008e2012,testamosestatisticamentearelac¸ãoentre novedimensõesdedistânciainstitucionaleograudepropriedadeadquirido.Osresultadosmostramefeitosdiferenciados,mascomevidência significativaquemaiordistânciageográficaconduzàtomadadeposseparcial,enquantomaiordistânciafinanceiraeculturalàtomadadeposse

∗Correspondingauthorat:MorrodoLena,AltoVieiro,2411-901Leiria,Portugal. E-mail:manuel.portugal.ferreira@gmail.com(M.A.Ferreira).

PeerReviewundertheresponsibilityofDepartamentodeAdministrac¸ão,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸ãoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeSãoPaulo –FEA/USP.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rausp.2016.09.001

total.Esteestudotemduascontribuic¸ões:reforc¸aoentendimentodosdesafiosinstitucionaisdeentraremeconomiasemergentes,epropõecomo asestratégiasdasempresaspodemincorporarmodosestruturaisqueminimizamriscoseinvestimentosemrelac¸ãoasincertezasinstitucionais.

©2016DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP.

PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Palavras-chave: Ambienteinstitucional;Distânciainstitucional;Aquisic¸õesinternacionaisdeempresas;Brasil;Estratégiadereduc¸ãodeincerteza

Resumen

Enesteartigoseanalizacómolasempresamultinacionales(EMNs)extranjerasrespondenalaincertidumbreenlasadquisicionesdeempresasen economíasemergentesy,específicamente,enBrasil,antelasdiferenciasinstitucionalesqueseparanlospaísesdeorigenydestinodelasinversiones. Seevalúacómoladistanciainstitucionalinfluyeenlaestrategiadelasmultinacionalesextranjerasenlatomadepropiedadparcialototaldel capitalenlasadquisicionesenBrasil.Seproponequeelgradodepropiedadesunarespuestaestratégicafrentealaincertidumbredeoperaren mercadosinstitucionalmentemáslejanos.Enunestudioconbaseendatossecundariosde736adquisicionesrealizadasentre2008y2012,seha puestoestadísticamenteapruebalarelaciónentrenuevedimensionesdedistanciainstitucionalyelniveldepropiedadadquirido.Losresultados muestranefectosdiferenciados,peroconevidenciasignificativadequemayoresdistanciasgeográficasconducenalatomadepropiedadparcial, mientrasqueunamayordistanciafinancierayculturalconducealatomadepropiedadtotal.Esteestudioaportadoscontribuciones:subrayael entendimientodelosdesafíosinstitucionalesdeentrareneconomíasemergentes,yproponecómolasestrategiasdelasempresaspuedenincorporar formasestructuralesquedisminuyanriesgoseinversionesfrentealasincertidumbresinstitucionales.

©2016DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP.

PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Esteesunart´ıculoOpenAccessbajolalicenciaCCBY(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Palabrasclave: Ambienteinstitucional;Distanciainstitucional;Adquisicionesinternacionalesdeempresas;Brasil;Estrategiadedisminucióndeincertidumbre

Introduction

Thispaperanalyzestheassociationbetweeninstitutional dis-tanceamongcountriesandthe degreeofequity ownershipto reduceinstitutionaluncertaintyinthecross-borderacquisitions bymultinationalcorporations(MNCs)inanemergingeconomy. Specificallythestrategic responseresearchedisthedegreeof equityownershipbasedonthepremisethatanacquisitionmay involveeitherapartialorafullequitystakeintheacquiredfirm (Hennart&Larimo,1998;Phene,Tallman,&Almeida,2012). Thispaperthusanalysestheassociationbetweeninstitutional distanceandthestrategyofundertakingapartialorfull acqui-sitionbyforeignMNCsinanemergingeconomy,specifically Brazil.

Albeit MNCs hold firm-specific advantages (Rugman, Verbeke, & Nguyen, 2011; Verbeke & Brugman, 2009) that allowsthemtoovercometheliabilitiesofforeignness(Meyer, Mudambi,&Narula,2011;Zaheer,1995),thoseadvantagesmay havelimitedusedwhenexposedtoinstitutionalenvironments thatdepartmoresubstantiallyfromthehomecountry(Rugman etal., 2011),such as inemergingeconomies (Beule,Elia,& Piscitello,2014).Inthesemarkets,MNCsaremoresusceptible tothedisadvantagesof foreignness(Zaheer,1995).Theseare disadvantagesrelatedtoalackofknowledgeonthe“normal” waysofconductingbusiness,lackoflegitimacy,unfamiliarity withthenormative,regulatoryandcognitiveaspects(Kostova, 1999).Thedisadvantagesrequirethatfirmsformulatea strate-gicresponsethatpromotesaccesstothehostcountry’sspecific advantages(Rugman&Verbeke,2001;Rugmanetal., 2011) and, simultaneously, protects the MNC fromthe institutional insufficiencies of the host countries (Peng, Wang, & Jiang, 2008),inparticularintheemergingeconomies.Itisthus reason-ablethat thestrategyforeachacquisitionwilldiffer(Ferreira, 2007;Pheneetal.,2012),asitisreasonabletosuggestthatthe

degreeofequityacquiredineachacquisition–partialorfull– needstobeadjustednotonlytothestrategicobjectivesbutalso totheexternalinstitutionaluncertaintiesandrisks.

Partialacquisitionshavebeentreatedintheliteratureas effec-tive mannersto avoida loss of value post-acquisition (Dyer, Kale, &Singh,2004;Ferreira, 2007;Vermeulen&Barkema, 2001),asmeanstoabsorbthetargetfirmspecificknowledgeand learnininstitutionallydistantenvironments(Jakobsen&Meyer, 2008; Pheneetal.,2012).However,theliteratureisscarcein revealing how the structural formof the acquisition– inthis study focusingonlythedegreeof equityownership–maybe seenas astrategy toreduceinstitutional uncertainty.Thus,in thispaper,weexamineonespecificaspectofastructural solu-tion in the acquisitionstrategy. That is,how the institutional distance between countries impact the degree of ownership incross-borderacquisitions.Wefurtherproposethat thenine dimensionsofinstitutionaldistancedescribedandmeasuredby Berry, Guillen,andZhou(2010) – cultural, economic, finan-cial,political,administrative,demographic,knowledge,global connectionsandgeographic–arepositivelyrelatedwith under-taking afullcross-borderacquisitioninemergingeconomies, usingthecaseofcross-borderacquisitionsinBrazil.

Thisstudywasbasedonsecondarydatacollectedfromthe SDCPlatinumofacquisitionsinBrazilbetween2008and2012. Theinstitutionaldimensionsconsideredfollowedthetaxonomy of institutional distances of Berry et al. (2010). The sample comprised736acquisitionsofBrazilianfirmsbyforeign multi-nationals.

undertakeafullacquisitionoftheBrazilianfirms,overapartial equitystake. Hence,inconditions ofhighinstitutional uncer-tainty, the MNCs may prefer the internalization and control overthe operationsor sharetheresponsibility withapartner, dependingonthespecificinstitutionaldimensionconsidered.

Thisstudycontributestotheanalysisontheimpactof insti-tutionaldistancesbetweencountriesinthestrategicactionsof firms. We follow the rationale that the institutional environ-mentisnot deterministicandthat firmsmay actstrategically (see Kostova, 1999; Oliver, 1991, 1997; Peng et al., 2008). Itfurthercontributestointegratetheliteratureonacquisitions withthatoninstitutionaldistance,permittingtounderstandthe structuralsolutionsemployedbytheMNCsinentering emerg-ingeconomies through acquisitions. Wepropose andtestthe degreeofequity ownershipas astructuralresponseto institu-tional uncertainty in the host country. Thus, dialoguing with the literature on entry modes, the results of this paper con-tributebygoingbeyondthecontrastamongentrymodes(Dikova &Witteloostuijn, 2007) andresearching different degrees of ownershipinacquisitions(Beuleetal.,2014;Chari&Chang, 2009).This study reveals that when the acquisitions involve firmsinemergingeconomies,thestructuralsolutiontoreduce uncertaintymaybedifferentfromthatportrayedintheliterature. Astopractitionerimplications,thisstudyshowsthatfirmsmay reactusingthebeststructuralsolutiontominimizeinstitutional risksanduncertainties.

The paper hasfive sections. The first section comprises a briefliteraturereviewandconceptualdevelopment.Thesecond sectiondescribesthemethod,includingdataandvariables.The thirdpresentstheresultsandisfollowedbyabroaddiscussionon theimpactofinstitutionaldistanceoncross-borderacquisitions andontheequityownershipstake.

Literaturereviewandconceptualdevelopment

Degreeofequityownershipinacquisitions

Cross-borderacquisitionsareoneoftheprimaryformsfirms use to access other firms’ resources and advantages (Anand &Kogut,1997;Barkema&Vermeulen,1998;Ferreira,2007; Vermeulen&Barkema,2001)andlocation-specificadvantages (Pheneetal.,2012).Anacquisitionmayinvolvedifferentlevels ofproperty– maybe afullacquisitionof 100%ofthe target firm’sequity,orapartialacquisitionthatinvolveslessthanthe totalityofthetargetfirm’sequity(Barkema&Vermeulen,1998; Chen&Hennart,2004).Thedifferentformsofacquisitions–full orpartial–aremotivatedbydifferentexogenousfactors(Chen, 2008),buttheyalso entail differentlevels of risk (Chapman, 2003;Chen&Hennart,2004),transferofresourcetoandfrom theacquiredfirm(Pheneetal.,2012),andcontroloverthe for-eignoperations (Chen &Hennart, 2004; Jakobsen&Meyer, 2008).

Apartial acquisition maybe preferred toaccess location-specificadvantagesthatlocalfirmsabsorbed.Itmayalsobean intermediatestep;thatis,aninitialinvestmentthatisfollowed bythefullacquisitionofthetargetfirm(Hoffmann& Schaper-Rinkel,2001).Apartialacquisitionpossiblyhasthe strategic

objectiveofabsorbingtheresourcesandcapabilitiesofthetarget firm,butinsuchmanneras toprevent thelossof value post-acquisition(Dyeret al.,2004; Ferreira,2007).Hence, partial acquisitionsseemtobebettertoprospectresourcesand capabil-itiesnotyetheld(Pheneetal.,2012),especiallyunderconditions ofuncertainty.Forexample,ChenandHennart(2004)confirmed that the propensityof the Japanesefirms toacquireless than thetotality ofthetargetfirmsintheUSAwasexplainedbya difficultytoassessthevalueoftheacquisition.

In other turn, full acquisitions involve the intent of the investor tokeepthe totalcontrolof the targetfirm(Jakobsen &Meyer,2008).Thefullownershippermitsthe totalcontrol of theoperationsbutitisnotaseffectiveas apartial acquisi-tiontoaccesscomplementaryresourcesbysharinginvestments andrisks(Anderson&Gatignon,1986;Pheneetal.,2012).The needforlargerinvestmentsandgreaterexposuretotherisksand liabilitiesofforeignnessaresomeofthecostsassociatedtofull ownership(Anderson&Gatignon,1986;Slangen&Hennart, 2007).In additiontothesedisadvantages, thereisthe lossof valueofthetarget’sassetspost-acquisition(Dyeretal.,2004), duetoalossofhumancapitalandknowledge.Inthismanner, fullacquisitionsseemtobethebeststrategicresponsetoexploit abroad the portfolio of products, technologiesand resources acquired(Pheneetal.,2012).

Hence, the degree of equity ownership depends on the strategic objectives of the MNCs but these are not the only determinant.Theconditionsofinstitutionaluncertaintyarealso importantdriversofthechoiceforundertakingafullorpartial acquisition.

Institutionalenvironmentinemergingeconomies

Theinstitutionsarecrucialtosustainthefunctioningof mar-ketsandreducetransactioncosts(North,1990)and,asnotedby Pengetal.(2008),decreasetherisksanddefinetheboundaries ofwhatistakenaslegitimate.Thecharacteristicsofthecontext inwhichfirmsoperate,or“therulesofthegame”(North,1990) –thelocalinstitutionalconditions(Pengetal.,2008)–, deter-minewhichstrategiestodeploy(Meyer&Peng,2005;Peng, Sun,Pinkham,&Chen,2009).Followingtheinstitutional the-ory, the MNCs need togain legitimacy(Dacin, 1997) in the hostmarketstosurviveandprosper,adaptingtotheprevailing normsandsystemsofthosemarkets(Dimaggio&Powell,1983; Kostova,1999;Meyer&Rowan,1977;North,1990).

specific institutional dimension, institutional differences gen-erateuncertaintyandtransactioncoststhat arebarriersMNCs needtoovercome.Hence,thequalityoftheinstitutionalsystem influence the uncertainties, costs andrisks of operations and thusdeterminetherelativebenefitsofeachforeignentrymode (Bevan,Estrin,&Meyer,2004;Meyer,2001).

Recent researchhasnotedthat intheemerging economies theinstitutional mattersare especiallyrelevantgiventhe pro-nounceddifferencesthatdistinguishtheseeconomiesfromtheir moredevelopedcounterparts(Gelbuda,Meyer&Delios,2008; Khanna,Palepu,&Sindha,2005;Meyer&Peng,2005;Wright, Filatotchev,Hoskisson,&Peng,2005).Theinstitutional con-text of the emerging economies is marked by institutional debilities – already termed as institutional voids - that con-trastwiththedegreeofinstitutionalsophisticationofthemore developed countries (Khanna et al., 2005; Meyer & Peng, 2005).

The institutions are not specificto countries(Berry etal., 2010;Cuervo-Cazurra,2016)andtheinstitutional differences betweencountriesaugmenttheperceivedrisksandcosts(Deng, 2009),duetoalackofknowledgeonhowthelocalinstitutions operate(Contractor,Lahiri,Elango,&Kundu,2014).Themore pronouncedthedifferences,the greater willbethe uncertain-tiesconcerning the localhostmarket, partner’resources, and learningpotential(Contractoretal.,2014).Theacquisitionsin emerging economiesare thus morecomplex for MNCs from developedcountriesdueto:alessdevelopedcapitalmarket,pool of labor less qualified, less sophisticated legalinfrastructure, bureaucracy,inefficientenforcementofcontracts,weak protec-tionofpropertyrights,corruption,etc.(Contractoretal.,2014; Meyeretal.,2009).Theculturalcharacteristicsofthe emerg-ingeconomiesarealsodistinctfromthedevelopedcountriesand manifestinsuchaspectsasdifferentattitudes,valuesystemsand behaviors.Firms–suppliers,clientsandcompetitors–in emerg-ingeconomiestendtobe(despitesomecasesofgrandsuccess such asJBS/Friboi,Embraer andGerdau,allBrazilianfirms) internationally little competitive(Khanna etal., 2005; Meyer etal.,2009).

Give the institutional differences between countries, researchershavesoughttounderstandtheforeignentry strate-gies deployed by MNCs in the emerging economies (Meyer etal.,2009).Specifically,inthisstudyweargueaboutthedegree ofequityownershipincross-borderacquisitionsgivenasetof institutionaldistances,takingthespecificcaseof Brazilasan emergingeconomy.

Institutionaldistanceandthedegreeofownershipin acquisitions

Research in international business has evolved beyond descriptions of the countries’ institutional characteristics to seek to understand the many dimensions (Ghemawat, 2001; Guisinger,2001; Kostova,1996; North,1990)of institutional distance–ordifference–betweencountries(Berryetal.,2010; Dikova, Sahib, & Van Witteloostuijn, 2010; Kostova, 1996; Morosini,Shane,&Singh,1998;Tihanyi,Griffith,&Russell, 2005).Thedifferencesbetweencountrieshavebeenmeasured

usingtheconceptofinstitutionaldistance(Drogendijk&Martín, 2015),thatmaybedefinedasthedegreeofsimilarityor dissim-ilaritybetweentheinstitutionsoftwocountries.Somescholars havecreatedtaxonomiestocharacterizetheinstitutional dimen-sions, suchastheCAGEmodelbyGhemawat(2001),thesix dimensionsbyDowandKarunaratna(2006)orthenine dimen-sionsbyBerryetal.(2010).The importanceofcapturing the multidimensionality of theinstitutional environmenthasbeen highlighted by Berryet al.(2010,p. 1461)as:“definingand measuringcross-nationaldistancealongmultipledimensionsis important,because differenttypesof distancecanaffectfirm, managerial or individualdecisionsindifferentways, depend-ing onthe dimension ofdistance underexamination”. Inthis vein,Berryetal.(2010)proposedataxonomyofnine dimen-sionsofinstitutionaldistancebetweencountries:(1)economic, (2) financial, (3) political,(4) administrative,(5) cultural, (6) demographic, (7) knowledge, (8) global connections,and (9) geographic.Thisdisaggregationoftheconstructofinstitutional distancepresentsamorecompleteclassificationthat encapsu-latesothertaxonomies(forinstance,Ghemawat’s(2001)CAGE model) andthus permitsamoredetailed analysisof how the differentfacetsoftheinstitutionalenvironmentmayinfluence MNCs’strategies.

Albeit well established that MNCs use the foreign entry modes best suited to the conditions of the host markets to gain legitimacy (Meyer & Rowan, 1977) and be accepted (Dacin, 1997),the literatureis notconsensualon whatis the best strategic response tothe institutionaldifferences, or dis-tances,althoughOliver(1991,1997)hassuggestedthatMNCs are not prisonersof their immediate institutional milieu. For instance,itisnotstraightforwardhowcross-boreracquisitions must be conducted, even if they are a commonly deployed strategy for international growth (Hitt, Ireland, & Harrison, 2001). Albeit reasonable to suggest that a possible strategic action under conditions of uncertainty may drive the equity stakeacquired inan acquisition,theextant theoryisnot con-sensualinpointingoutwhatisthestructuralsolutionpertaining the degree of equity ownership in conditions of institutional uncertainty. Nonetheless, it seemsreasonable to suggest that the institutional environment is likely to influence the level of control desired for a given foreign operation (Kostova, 1999).

thetargetfirmandhostcountry(Barkema&Vermeulen,1998; Ferreira,2007;Pheneetal.,2012)whilemaintainingflexibility (Zhao,Luo,&Suh,2004).

Thestructuralsolutiontoreduceuncertaintymaybe differ-entwhentheacquisitionsinvolvefirmsinemergingeconomies, than when involving firms in developed countries. In many emergingeconomies, the informationasymmetriesinopaque marketsmakemoredifficulttoobtaininformationonpotential partnersthusraisingtherisks ofcollaborating(Meyer,2001). Aweakinstitutional framework,volatileandarbitrary,makes impracticablecollaborativeentrymodesgiven,forinstance,the hazardsinguaranteeing theenforcementofcontracts(Meyer, 2001). The ability to regulate the partnership may also be especiallyhinderedinvoidinstitutionalenvironments.In condi-tionsofhighinstitutionaluncertainty,maintainingapartnership (e.g., a partial acquisition) does not guarantee the ability to overcomeregulatoryinefficiencies,arbitrarynormsand bureau-cracy(Meyer,2001;Peng,Wang&Jiang,2008).Furthermore, theinstitutional differenceswill likelyjeopardize the internal transferofknowledge andbest practicestoothersubsidiaries (Kostova, 1996, 1999; Kostova & Zaheer, 1999), discourag-ing MNCs from seeking partial acquisitions to absorb new knowledgeinemerging economies.Hence,albeit acquiring a firminanemergingeconomyexposestheMNCtogreat man-agementchallengesoftheacquiredfirm(Capron,Mitchell,& Swaminathan, 2001); a partial acquisition also entails coor-dinationchallengesanddifficultiesinmanaging thepartners’ objectives.

DeliosandBeamish (1999),for example, havenoted how the partial ownership(specifically, the joint ventures) were a means to access the resources of the local firms, including their networks that help in overcoming the voids of a weak institutionalcontext.Notwithstanding,inhighuncertainty con-ditionsfirmsneedtotrusttheabilitytogoverntheirpartnerships andenforcecontracts.Thereforethe suggestionthatthe need for a local partner decreases with the strengthening of the institutionalenvironment(Meyer,2001)hasanotherfacetthat is the own ability to regulate the relationship between part-ners,that is likelytobe difficult ininstitutionally very weak environments.

Combining these arguments it seems reasonable to sug-gest that an high, and idiosyncratic, institutional uncertainty associate to entering emerging economies leads to maintain internalized the foreign operation resorting to a full acqui-sition. This proposition follows Transaction Costs Theory (Williamson, 1985) that under conditions of uncertainty the firms is likely to prefer maintaining internalized the opera-tions.The institutional differences betweeninvestor andhost emerging countries make integration, legitimacy and perfor-mance more difficult for MNCs (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999). We thus propose that firms will prefer foreign entry modes of greater commitment when the institutional differences are larger.Thatis,thepreferredforeignentrymodemaybebased onfullycontrollingthesubsidiaryforgreaterinstitutional dis-tancesbetweenthehomeandhostcountries.Inotherwords,the largerthedistance,thehigherthepropensitytoconductafull acquisition.

Method

Tocollectthedataandpursuetheresearchgoalwefollowa quantitativeapproachseekingtoassessthetiesbetween insti-tutionaldistanceandthedegreeofequityownershipacquired. We now describethe data collection proceduresand sample, and detail de dependent, independent and control variables employed.

Datacollectionandsample

The datawas collectedfromsecondarysources.Data per-tainingtotheacquisitionsofBrazilianfirmsbyforeignMNCs wasextractedfromSDC Platinum(SecuritiesDataCompany Platinum)–mergersandacquisitions.Thisisadatabasewith restrictedaccessbutwidelyusedinpriorstudies(e.g.,Capron &Guillén,2009;Capron&Shen,2007).Thedatabasecontains allacquisitiondealswithUSfirmsastargetssince1979andnon USsince1985untilpresent.FromSDCplatinum,wecollected datapertainingtotheacquiringandacquiredfirms.

Data collection followed some procedures to select and delimitthesample.First,weonlywantdealsinwhichthetarget firmisheadquarteredorlocatedinBrazilandtheacquiringfirm isforeign.Second,weexcludedalldealsinvolvingMNCsin off-shores.Third,weexcludedalldealsinwhichthecurrentstatus wasunknown,rumors,intentsandallsortsofambiguousstatus. Fourth,we delimitedtheperiodtotheacquisitions completed between2008and2012.Theperiodandthesamplewereselected intentionallytopermitbothasubstantialsampleforstatistical testsandtoconstructanacquisitionexperiencevariablewiththe datafrom1985to2007.Itisworthnotingthatwehadaccessto thedataupto2012only.Fifth,wedidnotincludedeals involv-inganacquirerofthefinancialsector.Finally,weexcludedthe dealswithinsufficientdatainthevariablesof interest.Albeit very used thisdataset is alsovery incompleteandoftendoes notrevealvaluesofacquisitions,percentagesacquiredandso forth,andhencewehavedecidedtodichotomizethedependent variableinfullandpartialacquisition.

With theseprocedures, we obtained afinalsample of 736 acquisitions ofBrazilianfirmsbyforeignmultinationalsfrom 38countries.ThemaininvestorsweretheUSA,Canada,France andUK.493(or67%)acquisitionsinvolvedundertakingafull equitystakeand243(33%)werepartialacquisitions.

The data pertaining to the institutional distances between the home countries of the MNCs and Brazil were collected from Berry et al. (2010), publicly available at http://lauder. wharton.upenn.edu/ciber/research/faculty.php#(Cross-national distancedata).

Variables

enrichedscrutinizingtheactualpercentagesofequityheld.Data forequityacquiredwascollectedfromSDCPlatinumandcoded inadichotomousvariablesuchthat0–partialacquisitionand 1–fullacquisition.Partialacquisitionsinvolvelessthan100% ofequityacquired.

Independentvariables

Theindependentvariablesincludetheinstitutionaldistance assessedusingBerryetal.’s(2010)taxonomyofnine dimen-sions.Thedatausedconsistedinadistanceforeachinstitutional dimensionbetweenthehomecountryoftheacquirerMNCand Brazil.Itisworthnotingthatthemajorityoftheacquirerswere fromdevelopedcountries.

Economicdistancerevealsdifferencesinthedegreeof eco-nomic developmentandstability. Wehaveusedthe valuesin Berryetal.(2010)calculatedwithsuchitemsasGross domes-ticproduct(GDP)percapita,inflation,exportsandimportsof theinvestorcountriesandBrazil.Financialdistanceassesses firms’capacitytofinancetheiroperationsinthetargetcountry, availabilityandefficiencyofthefinancialsector.Datawas col-lectedfromBerryetal.(2010)andincludeprivatecredit(%of GDP),stockmarketcapitalization(%ofGDP)andnumberof firmslistedpermillioninhabitants.Politicaldistancereflects differencesinthepoliticalsystem,stabilityandpredictabilityof thepublic policies,normsandregulations.Thedatacollected fromBerryetal.(2010)useindicatorsas uncertaintyof poli-cymaking,numberofinstitutionalactors,vetopower,extentof democracy,sizeofgovernment,andsoforth.Datafor admin-istrative distance collected fromBerry et al.(2010) include aspectssuch as common language,religion,colonial tiesand legalsystem. Kwok and Tadesse(2006) argued that astrong legalsystemreducestheuncertainties.

Culturaldistancehasbeenoneofthevariablesmoreoften usedininternationalbusinessresearchandnotedasaneffective measureofinstitutionaldifferencesamongcountries(Kogut& Singh,1988).SincedataforculturewasnotavailableforBrazil inBerryetal.wecalculatedculturaldistanceusingKogutand Singh’s(1988)EuclideandistanceandHofstede’s(1980)four primaryculturaldimensions.AlbeitHofstede’staxonomywas addedoftwodimensions,(Hofstede&Bond,1988;Hofstede, Hofstede,&Minkov,2010)thereisnotdataavailableformany countriesinthesetwodimensions.

Demographic distance expresses differences in demo-graphicaspectsamongcountriessuchasincome,age,gender, salaries, productivity, availability of labor (data from Berry etal.,2010).Knowledgedistancereferstodifferencesof tech-nologicalsophisticationandgenerationof innovationsamong countries(Anand&Kogut,1997).DatausedfromBerryetal. (2010)thatusedindicatorssuchasthenumberofpatentsand scientific papers published.Global connectionsdistance, or connectivitybetweencountries,showsdifferencesinthelevelof integrationintheglobaleconomy,easingoperationsand reduc-ingsomecostfactors(e.g.,communications,trade,international outsourcing),butisalsoanindicatorofthequalityofthe infra-structure. Lastly, geographicdistance that albeit not strictly relatedtoinstitutionaltheoryisafactorthatislikelytoreveal

important differencesbetweencountries.Geographicdistance between countries increase transportation costsand telecoms (Berryetal.,2010)andisanoften-usedproxytohighlightthat countriesdiffer.WeusedBerryetal.(2010)data.

Controlvariables

We have used a number of control variables capable of influencingthedegreeofequityownershipinacquisitions.We controlledforthesizeoftheacquirerMNCbecauselargerfirms havemoreavailableresourcesforundertakingafullacquisition (Beuleetal.,2014;Kogut&Singh,1988).SincetheSDC plat-inumdoes notincludedataon sizesuchas assets,numberof workersorotherconventionalmeasure,weusedthenumberof 4-digitsSICcodestoproxysize(datafromSDCPlatinum).This proxyisreasonablesincewemayexpectthatthelargerthe num-berbusinessesthefirmsbeinvolvedinthelargertheywillbe. Thisvariablewas measuredcounting thenumberof different SICcodesofeachfirm,andvariesbetween1and14.

Wealsocontrolledforindustrybecausethespecificitiesof eachindustrymayinterfereintheforeigninvestmentstrategies ofMNCs.Forinstance,itispossiblethattechnologicaland pro-ductionaspectsdriveMNCstoprotect,internalizing,theirassets thususingfullacquisitionstoexpand.Theindustrieswerecoded asmanufacturing,naturalresources,services,tradeandothers. Data for industrywasextractedfromSDCPlatinum.We fur-therincludedacontrolforhightechnologytoaccountforthe knowledge intensityof bothacquirerandacquiredfirms. The resource-Basedviewsuggeststhatfirmsholdingricher compe-tences tend topreferfullcontrol over theforeign operations, namelyasamannertopreventunintendeddiffusionof knowl-edgetocompetitors(Brouthers&Hennart,2007).Wecodedina dichotomousvariablewhetherthefirmishightechnology(1)or nothightechnology(0)withdataavailableintheSDCdatabase thatclearlyspecifiesthefirmshightechnologystatus.

Wehavealsoincludedacontrolforthedegreeof diversifica-tion.Thisdenotestherelativeproximitybetweenthebusinesses oftheacquirerandacquiringfirms.Iftheacquisitioninvolves greaterdiversificationthenapotentialmotivewouldbetoaccess novelknowledge,whichisbetterexecutedwithpartial acquisi-tions(Chari&Chang,2009;Ferreira,2007).Usingdatafrom SDC Platinum, we included two measures of diversification. Diversification of the coreprimary business of the acquir-ing firm compares the main business of the acquirer to the main business of the acquired firms using the main 4-digits SIC(StandardIndustrialClassification)ofbothfirms.Wehave conducted robustnesstestsfor3-digitsSICcodeswithsimilar results.Generaldiversificationcomparedallbusinessesofeach firmtoassessthedegreeofdiversificationfortheacquiringMNC whencomparingtheentireportfolioofbusinesses.Thetwo vari-ableswerecodeddichotomouslyin1–acquisitionentailssome diversification,and0–doesnotentaildiversification.

learninginconductingacquisitions,whichpredictablydecreases the perceived risks in undertaking acquisitions. Acquisitions experiencewasmeasuredsummingthenumberofprior acqui-sitionseachMNChadmadeinBrazilbetween1985(firstyear availableinSDCPlatinum)andthefocalacquisition.Giventhat, wehadonlypartialaccesstothedatabasewecouldnotcalculate abroaderacquisitioncapabilitythatconsideredallacquisitions conductedbyeachMNCworldwide.Nonetheless,local expe-rienceis a moredirect measure of relevant experience since prioracquisitions inBrazilshoulddiminish theMNCs sensi-tivity tothe local idiosyncrasiesthat are potential sources of uncertainties.DatawerecollectedfromSDC.

Lastly,weusedtheyeartheacquisitionwasannouncedasa controltoaccountforpotentialeconomiccyclescapableof influ-encingourmodel.Weincludedfourvariablesforyears2008, 2009,2010and2011,using2012asthebaseline.

Results

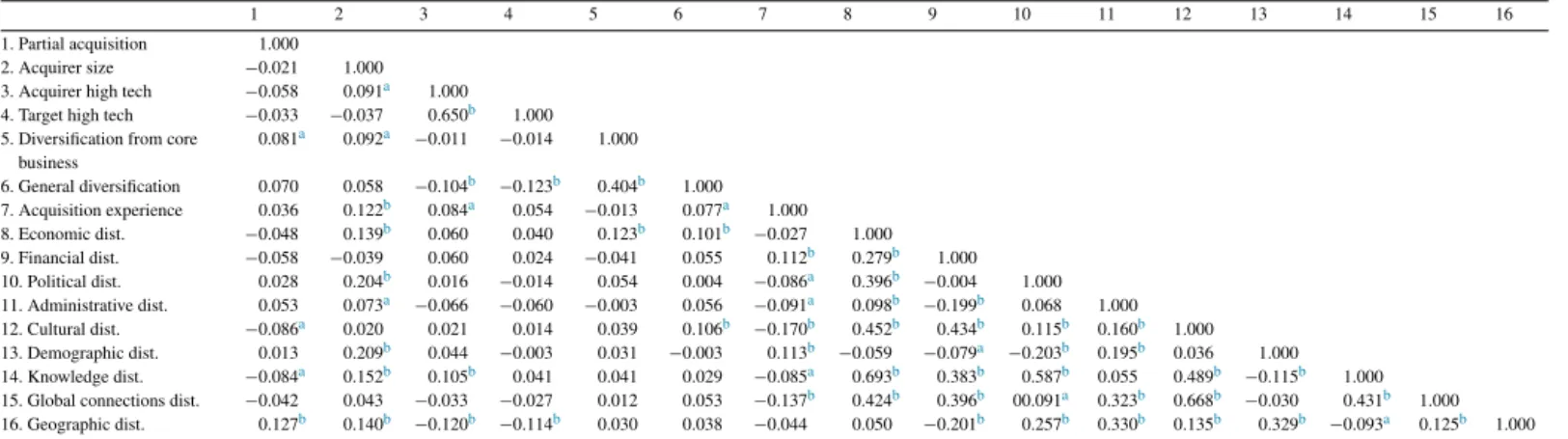

The statistical analysis involved multivariate techniques using alogistic regression. A logistic regression is appropri-atetoestimatetheeffectsofasetofvariablesonadichotomous dependentvariable. Thetestsanalyzehow theforeignMNCs respond to institutional uncertainties in their acquisitions in Brazilselectingdifferentdegreesofequityownershiponthe tar-get:fullorpartial.Table1presentsthecorrelationsmatrix.The correlationsarenotashighastoraisemulticollinearityconcerns andthecollinearitydiagnosis(specificallytheVarianceInflation Factor–VIF)arelowerthanthree.Thus,thereisnoevidence ofmulticollinearityinthedata.

Table2includestheresultsofthelogisticregressionforthe dependentvariable:degreeofequityacquired(fullorpartial). Model1includesonlythecontrolvariables.Models2–10add eachofthemeasuresofinstitutionaldistanceseparately.Model 11isthecompletemodelandincludesallindependentvariables. Wehighlightthatthecontrolvariablesforhightechnologyof theacquiredandtargetfirmsarenotsignificantwhichdenotes thattherelationsoughtafterisnotsensitivetotheknowledge intensityinvolvedinthedeal.Thevariablesonthediversification (orcorebusinessandgeneral)arealsonotsignificantpointing thattherelationisnotrelatedtoenteringintonewbusinesses. Pertainingtotheindustry,inadditiontonotbeingsignificant,a complementaryanalysiswehaveconductedandnotshownhere showsthatthemajorityoftheacquisitionstakesplaceinsidethe industry(usingthe4-digitsSICcodes)–thatis,inthemajority oftheacquisitionstheMNCsarenotenteringanovelbusiness butratherextendingonthebusinesstheyalreadyoperate.

Theresultsconfirmthatculturalandfinancialdistance influ-encethelikelihoodofafullacquisition.Thatis,thegraterthese twodistances,themorelikelytheMNCswillprefertotakefull ownershipoftheiracquisitionsinBrazil.Hence,wefound par-tialevidencefortheimpactofsomeinstitutionaldimensionson theequitystakeselectedandspecifically,thatgreater cultural distance(model 11)leadsMNCstoacquirethetotalityofthe Braziliantargetfirms.Theseresultsmayseemunconventional giventhepossibleexpectationthatunderconditionsofgreater uncertaintytheMNCswouldprefertosharetheriskswithlocal

partners– whichwould leadtopartial acquisitions.However, the results are compatible with the arguments related to the transactioncostsofoperating inemergingeconomiesandthe betterprotectiontotheproprietaryresourcesoftheMNCsusing modelsoffullcontroloftheoperationsinemergingeconomies. Onlythegeographicdistanceisrelatedtothelikelihoodthat theacquisitionswillentailapartialequitystakeoftheBrazilian subsidiary.Possiblygeographicdistanceincreasesthe difficul-tiesincontrollingandmanagingamoredistantsubsidiary,in additiontothecoststhatarisefromdistanceandthatthe com-municationtechnologiescannotovercome.Intheseinstances,a localpartnermaybeaviablealternative.

Wefailtoconfirmsignificanteffectsforthepossibleimpact on the degree of equity ownership of economic, political, administrative, demographic, knowledge, and global connec-tionsdistances.Notwithstanding,itisnotsurprisingthatthese institutionaldimensionsrevealaslessrelevantinselectingthe equity stake. At least in part, these institutional dimensions aremoreexplicitandeasiertoobserveandthusrepresentless uncertainty (see Rodriguez etal., 2005).In otherwords, the uncertaintyandriskassociatedtothesedimensionsmaybemore easilyidentified,analyzedandincorporatedintheverymarket selection decision.Therefore, the decisionto enter Brazilby means of an acquisitionpredictably already consideredthese uncertainties.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the influence of institutional distanceonthedegreeofequityownershipacquired in cross-borderacquisitions.ThisstudyproposedthatMNCsmightreact strategicallytohighlevelsofexternalinstitutionaluncertainty using structural solutions.Wehavespecificallyproposedthat theMNCswillacquirethetotalityofthetarget’sequityin con-ditionsofhighinstitutionaluncertaintyinemergingeconomies. Thisstudy,basedonsecondarydatacollectedfromSDC Plat-inum,analyzedandpermittedtoconcludethatinconditionsof institutional uncertainty– withdistinct effectsfor thevarious institutional dimensions – the MNCs tendtoacquire the full acquisitionofthetargetBrazilianfirms.

The results that sustain a positive effect of cultural and financialdistancewarrantadditionalconsiderations.First,they confirm that MNCs acquire greater equity ownership in the foreignsubsidiarieswhensomeinstitutionaldimensions, specif-icallyculturalandfinancial,differmoremarkedlyfromthoseof thehomecountriesoftheinvestorfirms.Theresultscontrastwith thecommonargumentthatunderconditionsofhigherriskthe MNCsprefertoengageinoperationscommittinglessresources toassurelowerriskandgreaterflexibility.

Table1 Correlations.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

1.Partialacquisition 1.000 2.Acquirersize −0.021 1.000 3.Acquirerhightech −0.058 0.091a 1.000

4.Targethightech −0.033 −0.037 0.650b 1.000

5.Diversificationfromcore business

0.081a 0.092a −0.011 −0.014 1.000

6.Generaldiversification 0.070 0.058 −0.104b −0.123b 0.404b 1.000

7.Acquisitionexperience 0.036 0.122b 0.084a 0.054 −0.013 0.077a 1.000

8.Economicdist. −0.048 0.139b 0.060 0.040 0.123b 0.101b −0.027 1.000

9.Financialdist. −0.058 −0.039 0.060 0.024 −0.041 0.055 0.112b 0.279b 1.000

10.Politicaldist. 0.028 0.204b 0.016 −0.014 0.054 0.004 −0.086a 0.396b −0.004 1.000

11.Administrativedist. 0.053 0.073a −0.066 −0.060 −0.003 0.056 −0.091a 0.098b −0.199b 0.068 1.000

12.Culturaldist. −0.086a 0.020 0.021 0.014 0.039 0.106b −0.170b 0.452b 0.434b 0.115b 0.160b 1.000

13.Demographicdist. 0.013 0.209b 0.044 −0.003 0.031 −0.003 0.113b −0.059 −0.079a −0.203b 0.195b 0.036 1.000

14.Knowledgedist. −0.084a 0.152b 0.105b 0.041 0.041 0.029 −0.085a 0.693b 0.383b 0.587b 0.055 0.489b −0.115b 1.000

15.Globalconnectionsdist. −0.042 0.043 −0.033 −0.027 0.012 0.053 −0.137b 0.424b 0.396b 00.091a 0.323b 0.668b −0.030 0.431b 1.000

16.Geographicdist. 0.127b 0.140b −0.120b −0.114b 0.030 0.038 −0.044 0.050 −0.201b 0.257b 0.330b 0.135b 0.329b −0.093a 0.125b 1.000

aSignificantat0.05. b Significantat0.01.

Table2

Logisticregressionfortheequityownershipacquired.

Model1 Model2 Model3 Model4 Model5 Model6 Model7 Model8 Model9 Model10 Model11

Acquirersize 0.001 −0.001 0.003 0.008 0.003 −0.003 0.006 −0.004 −0.002 0.011 0.017

Industry 0.878 0.859 0.922 0.878 0.934 1.006 0.913 0.893 0.934 0.879 1.137

Naturalresources −0.072 −0.073 −0.059 −0.118 −0.066 −0.041 −0.081 −0.013 −0.048 0.011 −0.014

Services 0.342 0.332 0.339 0.310 0.375 0.469 0.393 0.376 0.385 0.323 0.560

Trade 0.620 0.614 0.708 0.597 0.643 0.817 0.644 0.669 0.689 0.534 0.828

Others 21.325 21.366 21.458 21.233 21.378 21.500 21.433 21.415 21.314 21.555 21.701

Acquirerhightech 0.233 0.229 0.198 0.228 0.211 0.209 0.237 0.211 0.237 0.186 0.152

Targethightech −0.193 −0.196 −0.167 −0.198 −0.204 −0.224 −0.211 −0.183 −0.200 −0.208 −0.289 Diversificationfromcorebusiness −0.282 −0.301 −0.264 −0.272 −0.293 −0.286 −0.275 −0.291 −0.278 −0.265 −0.271 Generaldiversification −0.123 −0.135 −0.148 −0.130 −0.097 −0.184 −0.122 −0.130 −0.140 −0.120 −0.171

Yearsofacquisition Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Acqusitionexperience −0.027 −0.026 −0.038 −0.035 −0.037 0.003 −0.022 −0.021 −0.016 −0.035 0.001

Economicdist. 0.007 −0.004

Financialdist. 0.038a −0.015

Politicaldist. 0.000 −0.000

Administrativedist. −0.012 −0.011

Culturaldist. 0.299b 0.400b

Demographicdist. −0.012 −0.012

Knowledgedist. 0.010 0.005

Globalconnectionsdist. 0.078 −0.003

Geographicdist. −0.000b 0.000

n 736 736 736 736 736 736 736 736 736 736 736

R2 0.05 0.05 0.06 0.06 0.06 0.06 0.05 0.06 0.06 0.06 0.08

Chi-quadrado 39.377c 40.102c 43.388c 41.934c 42.976c 49.001c 40.779c 41.283c 41.802c 48.049c 64.272c

ap<0.05. b p<0.01. cp<0.001.

policies, and so forth that are hazardous for the operations (Capron&Guillén,2009).Moreover,weakinstitutionsdonot guaranteethequalityofthefinancialinformationaboutthetarget firms,potentialintermediaries(Khannaetal.,2005;Tong,Reuer, &Peng, 2008),nor about potential efficient incumbent local partners.Intheseinstancesofinsecurityregardingthe environ-mentandpartnersinemergingcountries,asBrazil,theforeign firmsarelikelytochoosefullyacquiringatargetfirm.

Culturaldifferencesarebroadlyrecognizedasdeterminants oftheforeign entrymodes,notingthatgreater cultural differ-encestendtoleadfirmstopreferentrymodesinvolvinglower commitmentofresources(Kogut&Singh,1988;Morosinietal., 1998).Nonetheless,muchoftheextantstudiesexplorethe pos-sibilityof learning when entering culturally distant countries (Barkema &Vermeulen, 1998; Ferreira, 2007; Vermeulen & Barkema,2001).Intheemergingeconomies,possiblythe learn-ingsoughtisthatrelatedtothemarketandcommercialization

toalargealbeitlowerincomepopulation.Therefore,asolution offullpropertymaysignalthatthereisnoemphasisonlearning butratheronexploitingtheresources andcapabilitiesalready heldbytheforeignMNCenteringBrazil.

potential.The evidenceforthisclaim isinthe lowdegreeof business-leveldiversificationbetweenacquirerandtargetfirms. Themajorityoftheacquisitionstookplacebetweenfirmsinthe samebusiness,thuscharacterizingtheseashorizontal acquisi-tions.

Hence,thelearningpotentialisessentiallyrestrictedto learn-ing about the market – for example, how to operate in the emergingeconomies,howtoservethelowerincomeconsumers –thatatthebusinesslevel.Thisanalysisisrelevantforfuture researchinsofarasitisimportanttounderstandwhatisthe learn-ingpotentialatthelocallevelforfurtherabsorptionandinternal transfertoothersubsidiariesgeographicallydisperse.

Conclusion

Researchininternationalbusinessandstrategyhasalready established the importance of understanding the institutional environmentandhowthedifferencesbetweentheinstitutional environmentsimpactthechoicesandstrategiesofthe multina-tionals.Tosucceed inthe foreignmarkets theMNCsneed to havecompetitiveadvantagescomparedtotheincumbentlocal firms.Foreign MNCsalsoneed tobeabletoovercome insti-tutionaldisadvantages.Albeit thecurrentattractivenessofthe emergingeconomiestheystillsufferfromanumberoffragilities andinefficienciesthatmaybeespeciallyhazardoustoovercome byMNCsthatarenotfamiliarwiththeinstitutionalfacetsofthe emergingeconomies.Inthisstudy,weproposedthatatleastin someinstancesamannertoovercomeinstitutionaluncertainties mightbeintakingstructuralformsthatpermitgreater adapta-tion or greater control overthe operations. Acquiringalocal firmtheforeignMNCmayaccessthe intangibleresources of theacquiredfirmasamannertoaugmentitslocallegitimacy. Thepotential costsofoperating inlessefficientandeffective environmentsandthelossesofflexibilitymaybeinferiortothe risksofundertakingpartialacquisitionsinemergingeconomies suchasBrazil.

The degree of equity ownership acquired in cross-border acquisitionsbytheMNCsentailsmanystrategicconsiderations (Chari&Chang,2009).Strategicmotivationssupportedinthe technological upgrade or in knowledge are possibly imple-mentedthroughfullacquisitions,especiallywhenitisnecessary to control the assets of the target firm (Meyer et al., 2009). Thetotalownershipavoidsthat MNCsincurinthe coordina-tionhazardswhenthereissharedproperty(Chen,2008),what maybeespeciallyrelevant ininstitutionalcontextswherethe legalsystemisnoteffectiveinpreventingopportunistic behav-iors(Williamson,1985).Totalownershipmayalsobepreferred whentheacquirerMNCseekstotransferinternallyknowledge, resourcesandcompetencestothesubsidiary (Ferreira,2007), andthis concern is higher for investments in less developed countries.

Partialacquisitions,incontrast,maybepreferredtoaccess complementary resources, and when the risk is high or the investmentslarger(Chari&Chang,2009).The literaturehas pointedthatpartialacquisitionsmaypromotelearningwiththe localpartners(Barkema&Vermeulen, 1998),witherlearning aboutthebusinessoraboutthemarket(Ferreira,2007).Partial

acquisitionsarealsoeasiertoreverse,whichmaybeimportant in environmentsthat are moreunstable. It isthus reasonable to seek tobetter understandhow the strategies implemented through cross-borderacquisitions vary accordingtothe insti-tutionalconditionsinthehostcountries.

Thisstudycontributestotheliteratureontheimpactofthe institutional environment in the internationalization of firms (Meyeretal.,2011)andinparticularintheinternationalization tolessdevelopedinstitutionalenvironmentsfoundinthe emerg-ingeconomies(Khoury&Peng,2011;Meyeretal.,2009;Peng etal.,2008).Ourresultscontrast,atleastpartially,withthose found in the extant literature that emphasized preferably the moredevelopedcountriesandshowthatinemergingeconomies the entriesthrough full acquisition is the structural response preferredtoreduceuncertainty.Hence,thereisacontribution to the construction of an institutional perspective in strategy (Oliver, 1991,1997; Penget al., 2009) anda contributionto the literatureonforeignentrymodesbyanalyzingthedegree ofequityownership(Jakobsen&Meyer,2008)without resort-ingtothemoreusualstudiescontrastingamongalternativeentry modes,suchascomparisonsbetweenacquisitionsandgreenfield investmentsorjoint-ventures.Finally,thisstudymakesa con-tributiontotheresearchonemergingeconomiesand,although theempiricalcontextwaslimitedtoonehostcountry,itraises newperspectives on theneed tounderstandin detailthe dif-ficultiesof operatinginthosecountries.Ourstudy showsthat itisnotsufficienttounderstandaggregatedimensionssuchas institutionaldistance,butratherthatisnecessaryadeepeningon thelocalspecificitiestocapturehowtheinstitutionaldifferences existandtheirimpact.

Limitationsandfutureresearchavenues

Thisstudyhaslimitations.First,thelimitationsimposedby insufficienciesintheavailabledatathatimpedeadditional anal-yses. Forinstance, it would be relevant toconsider how the strategic motivations– marketseeking,natural resource seek-ing,strategicassetseeking(Dunning,1993)–impactthedegree of equity ownershipinacquisitions incontext ofinstitutional uncertainty.Otherdatapotentiallyrelevantincludedataonthe economicperformanceandinnovationsince, ononeside,the evidenceontheimpactofacquisitionsonfirmsperformanceis not consensual(Chapman, 2003;Capron&Shen,2007)and, on other side, researchers have pointed to the potential that MNCsmayreconfigure theirportfolio of resourcesand com-petencesusingacquisitions(Barkema,Bell,&Pennings,1996; Dyeretal.,2004;Ferreira,2007;Haspeslagh&Jemison,1991). Futureresearchwillpossiblyrequiredatacollectedthrough sur-veytoassessthemotivationsandthebenefitsexpectedfromthe acquisitions.

emergingeconomies.Foreigninvestmentstillflowsmainlyfrom northtosouth,buttheremaybesubstantialdifferencesinthe strategicmotivationsofemergingMNCs.

Finally,usingrealoptionstheory,inconditionsofhigh uncer-taintyintheforeignmarketsitmaybebetterforMNCstocommit less resources tomaintain flexibilityand permit afaster exit fromthe hostcountryif theconditions becomemoreadverse (Tongetal.,2008).Smallerinvestmentsmaybeterminatedwith lowercostsifthehostcountryconditionsareworsethaninitially forecasted.However,ininstitutionallylessdevelopedcountries theremaybeinstitutionalbarriersthathinderdivestments(Peng etal.,2009)andmakeunviableadaptingtochanging environ-mentalandbusinessconditions.Thus,itisrelevanttoexaminein futurestudieshowMNCsmayplantheirstrategiesconcerning theequitystakesoftheirinvestmentstoprotectfromaworsening ofthehostinstitutionalconditions.

Conflictsofinterest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

Anand,J.,&Kogut,B.(1997).Technologicalcapabilitiesofcountries,firm rivalryand foreigndirectinvestment. JournalofInternational Business Studies,28(3),445–465.

Anderson,E.,&Gatignon,H.(1986).Modesofforeignentry:Atransaction costanalysisandpropositions.JournalofInternationalBusinessStudies,

17(3),1–26.

Barkema,H.,&Vermeulen,F.(1998).Internationalexpansionthroughstart-up oracquisition:Alearningperspective.AcademyofManagementJournal,

41(1),7–26.

Barkema,H.,Bell,J.,&Pennings,J.(1996).Foreignentry,culturalbarriers, andlearning.StrategicManagementJournal,17(2),151–166.

Berry, H.,Guillen, M., & Zhou, N. (2010). An institutional approach to cross-nationaldistance.JournalofInternationalBusinessStudies,41(9), 1460–1480.

Beule,F.,Elia,S.,&Piscitello,L.(2014).Entryandaccesstocompetencies abroad:Emergingmarketfirmsversusadvancedmarketfirms.Journalof InternationalManagement,20,137–152.

Bevan,A.,Estrin,S.,&Meyer,K.(2004).Foreigninvestmentlocationand institutionaldevelopmentintransitioneconomies.InternationalBusiness Review,13(1),43–64.

Brouthers,K.,&Hennart,J.F.(2007).Boundariesofthefirm:Insightsfrom internationalentrymoderesearch.JournalofManagement,33(3),395–425.

Capron,L.,&Guillén,M.(2009).Nationalcorporategovernanceinstitutions andpost-acquisitiontargetreorganization.StrategicManagementJournal,

30(8),803–833.

Capron,L.,&Shen,J.C.(2007).Acquisitionsofprivatevs.publicfirms:Private information,targetselection,andacquirerreturns.StrategicManagement Journal,28(9),891–911.

Capron,L.,Mitchell,W.,&Swaminathan,A.(2001).Assetdivesturefollowing horizontalacquisitions:Adynamicview.StrategicManagementJournal,

22(9),817–844.

Chapman,K.(2003).Cross-bordermergers/acquisitions:Areviewandresearch agenda.JournalofEconomicGeography,3(3),309–334.

Chari,M.,&Chang,K.(2009).Determinantsoftheshareofequitysoughtin cross-borderacquisitions.JournalofInternationalBusinessStudies,40(8), 1277–1297.

Chen,S.(2008).Themotivesforinternationalacquisitions:Capability procure-ments,strategicconsiderations,andtheroleofownershipstructures.Journal ofInternationalBusinessStudies,39(3),454–471.

Chen,S.F.,&Hennart,J.F.(2004).Ahostagetheoryofjointventures:Whydo JapaneseinvestorschoosepartialoverfullacquisitionstoentertheUnited States?JournalofBusinessResearch,57(10),1126–1134.

Contractor,F.,Lahiri,S.,Elango,B.,&Kundu,S.(2014).Institutional,cultural andindustryrelateddeterminantsofownershipchoicesinemergingmarket FDIacquisitions.InternationalBusinessReview,23(5),931–941.

Cuervo-Cazurra,A.(2016).Multilatinasassourcesofnewresearchinsights:The learningandescapedriversofinternationalexpansion.JournalofBusiness Research,69(6),1963–1972.

Dacin,T.(1997).Isomorphismincontext:Thepowerandprescriptionof insti-tutionalnorms.AcademyofManagementJournal,40(1),46–81.

Delios,A.,&Beamish,P.(1999).OwnershipstrategyofJapanesefirms: Trans-actional, institutional,and experienceinfluences. StrategicManagement Journal,20(10),915–933.

Deng,P.(2009).WhydoChinesefirmstendtoacquirestrategicassetsin inter-nationalexpansion?JournalofWorldBusiness,44(1),74–84.

Dikova,D.,&Witteloostuijn,A.(2007).Foreigndirectinvestmentmodechoice: Entryandestablishmentmodesintransitioneconomies.Journalof Interna-tionalBusinessStudies,38,1013–1033.

Dikova, D., Sahib, P., & Van Witteloostuijn, A. (2010). Cross-border acquisition abandonmentandcompletion:Theeffectofinstitutional dif-ferencesandorganizationallearningintheinternationalbusinessservice industry, 1981–2001. Journal of International BusinessStudies, 41(2), 223–245.

Dimaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1983). Theiron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphismandcollectiverationalityinorganizationalfields.American SociologicalReview,48(2),147–160.

Dow,D.,&Karunaratna,A.(2006).Developingamultidimensional instru-menttomeasurepsychicdistancestimuli.JournalofInternationalBusiness Studies,37,578–602.

Drogendijk, R.,& Martín,O.(2015). Relevantdimensions andcontextual weights of distance in international business decisions:Evidence from SpanishandChineseoutwardFDI.InternationalBusinessReview,24(1), 133–147.

Dunning,J.(1993).MultinationalEnterprisesandtheGlobalEconomy. Read-ing,MA:Addison-Wesley.

Dyer,J.,Kale,P.,&Singh,H.(2004).Whentoallyandwhentoacquire?Harvard BusinessReview,82(8),109–115.

Ferreira,M.(2007).Buildingandleveragingknowledgecapabilitiesthrough cross-borderacquisitions.InS.(Org.)Tallman(Ed.),Newgenerationsin internationalstrategy.NewYork,NY:EdwardElgarPublishing.

Gelbuda,M.,Meyer,K.,&Delios,A.(2008).Internationalbusinessand institu-tionaldevelopmentinCentralandEasternEurope.JournalofInternational Management,14(1),1–11.

Ghemawat,P.(2001).Distancestillmatters:Thehardrealityofglobalexpansion.

HarvardBusinessReview,79(8),137–147.

Guisinger, S.(2001).From OLIto OLMA:Incorporating higherlevels of environmentalandstructuralcomplexityintotheEclecticparadigm. Inter-nationalJournalofEconomicsofBusiness,8(2),257–272.

Haspeslagh,C.,&Jemison,B.(1991).Managingacquisitions.InCreatingvalue throughcorporaterenewal.NewYork,NY:TheFreePress.

Hennart, J., & Larimo, J. (1998). The impact of culture on the strat-egy of multinational enterprises: Does national origin affect the ownership decisions? Journal of International Business Studies, 29(3), 515–538.

Hitt,M.,Ireland,R.,&Harrison,J.(2001).Mergersandacquisitions:Avalue creatingorvaluedestroyingstrategy?InM.Hitt,R.Freeman,&J.Harrison (Eds.),HandbookofStrategicManagement(pp.384–408).Oxford,UK: BlackwellPublishersLtd.

Hoffmann, W., & Schaper-Rinkel,W. (2001). Acquireorally? Astrategy frameworkfordecidingbetweenacquisitionandcooperation.Management InternationalReview,41(2),131–159.

Hofstede,G.(1980).Culture’sconsequences:Internationaldifferencesin work-relatedvalues.BeverlyHills,CA:Sage.

Hofstede,G.,&Bond,M.(1988).Theconfuciousconnection:Fromcultural rootstoeconomicgrowth.OrganizationalDynamics,16(4),5–21.

Jakobsen, K., & Meyer, K. (2008). Partial acquisition: The overlooked entrymode.ForeignDirectInvestment,LocationandCompetitiveness,2, 203–226.

Khanna,T.,Palepu,K.,&Sindha,J.(2005).Strategiesthatfitemergingmarkets.

HarvardBusinessReview,83,6–15.

Khoury,T.,&Peng,M.(2011).Doesinstitutionalreformofintellectualproperty rightsleadtomoreinboundFDI?EvidencefromLatinAmericaandthe Caribbean.JournalofWorldBusiness,46(3),337–345.

Kogut,B.,&Singh,H.(1988).Theeffectofnationalcultureonthechoiceof entrymode.JournalofInternationalBusinessStudies,19(3),411–432.

Kostova,T.(1996).Successofthetransnationaltransferoforganizational prac-ticeswithinmultinationalcorporations.Unpublisheddoctoraldissertation. Minneapolis:UniversityofMinnesota.

Kostova,T.(1999).Transnationaltransferofstrategicorganizationalpractices: Acontextualperspective.AcademyofManagementReview,24(2),308–324.

Kostova,T.,&Zaheer,S.(1999).Organizationallegitimacyunderconditionsof complexity:Thecaseofthemultinationalenterprise.Academyof Manage-mentReview,24(1),64–81.

Kwok,C.,&Tadesse,S.(2006).Nationalcultureandfinancialsystems.Journal ofInternationalBusinessStudies,37(2),227–247.

Meyer,K.(2001).Institutions,transactioncostsandentrymodechoice.Journal ofInternationalBusinessStudies,31,357–368.

Meyer,K.,&Peng,M.(2005).ProbingtheoreticallyintoCentralandEastern Europe:Transactions,resources,andinstitutions.JournalofInternational BusinessStudies,36(6),600–621.

Meyer,J.,&Rowan,B.(1977).Institutionalizedorganizations:Formalstructure asmythandceremony.AmericanJournalofSociology,83(2),340–363.

Meyer,K.,Estrin,S.,Bhaumik,S.,&Peng,M.(2009).Institutions,resources, andentrystrategiesinemergingeconomies.StrategicManagementJournal,

30(1),61–80.

Meyer,K.,Mudambi,R.,&Narula,R.(2011).Multinationalenterprisesand localcontexts:Theopportunitiesandchallengesofmultipleembeddedness.

JournalofManagementStudies,48,235–252.

Morosini,P.,Shane,S.,&Singh,H.(1998).Nationalculturaldistanceand cross-borderacquisitionperformance.JournalofInternationalBusinessStudies,

29(1),137–158.

North,D.(1990).Institutions,institutionalchangeandeconomicperformance. CambridgeUniversityPress.

Oliver,C.(1991).Strategicresponsestoinstitutionalprocesses.Academyof ManagementReview,16(1),145–179.

Oliver,C.(1997).Sustainablecompetitiveadvantage:Combininginstitutional andresource-basedviews.StrategicManagementJournal,18(9),697–713.

Peng,M.,Wang,D.,&Jiang,Y.(2008).Aninstitution-basedviewof inter-nationalbusinessstrategy: Afocus onemergingeconomies.Journalof InternationalBusinessStudies,39(5),920–936.

Peng,M.,Sun,S.,Pinkham,B.,&Chen,H.(2009).TheInstitution-Basedview asathirdlegforastrategytripod.AcademyofManagementPerspectives,

23(3),63–81.

Phene,A.,Tallman,S.,&Almeida,P.(2012).Whendoacquisitionsfacilitate technologicalexploration andexploitation?JournalofManagement,38, 753–783.

Rodriguez,P.,Uhlenbruck,K.,&Eden,L.(2005).Governmentcorruptionand theentrystrategies ofmultinationals.AcademyofManagement Review,

30(2),383–396.

Rugman,A.M.,&Verbeke,A.(2001).Subsidiary-specificadvantagesin multi-national.StrategicManagementJournal,22(3),237–250.

Rugman,A.M.,Verbeke,A.,&Nguyen,Q.T.K.(2011).Fiftyyearsof inter-nationalbusinesstheoryandbeyond.ManagementInternationalReview,

51(6),755–786.

Slangen,A.,&Hennart,J.(2007).Greenfieldoracquisitionentry:Areviewof theempiricalforeignestablishmentmodeliterature.JournalofInternational Management,13(4),403–429.

Tihanyi,L.,Griffith,D.,&Russell,C.(2005).Theeffectofculturaldistance on entry mode choice, international diversification, and MNE perfor-mance:Ameta-analysis.JournalofInternationalBusinessStudies,36(3), 270–283.

Tong,T.,Reuer,J.,&Peng,W.(2008).Internationaljointventuresandthevalue ofgrowthoptions.AcademyofManagementJournal,51(5),1014–1029.

Verbeke, A., & Brugman, P. (2009). Triple-testing the quality of multinationality–performanceresearch:Aninternalizationtheory perspec-tive.InternationalBusinessReview,18(3),265–275.

Vermeulen,F.,&Barkema,H.(2001).Learningthroughacquisitions.Academy ofManagementJournal,44(3),457–476.

Williamson,O.(1985).Theeconomicinstitutionsofcapitalism.NewYork,NY: TheFreePress.

Wright,M.,Filatotchev,I.,Hoskisson,R.,&Peng,M.(2005).Strategyresearch inemergingeconomies:Challengingtheconventionalwisdom.Journalof ManagementStudies,42,1–33.

Zaheer,S.(1995).Overcomingtheliabilityforeignness.Academyof Manage-mentJournal,38,341–363.