342

Radiol Bras. 2017 Set/Out;50(5):338–348 Letters to the EditorAline de Araújo Naves1, Luiz Gonzaga da Silveira Filho1, Renata Etchebehere1, Hélio Antônio Ribeiro Júnior1, Francisco Valtenor A. Lima Junior2

1. Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro (UFTM), Uberaba, MG, Brazil. 2. Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Uni-versidade de São Paulo (HCFMRP-USP), Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil. Mailing address: Dra. Aline de Araújo Naves. Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mi-neiro. Avenida Getúlio Guaritá, 130, Nossa Senhora da Abadia. Uberaba, MG, Brazil, 38025-440. E-mail: rdi.alinenaves@gmail.com.

A indicates that the tumor is limited to the nasal cavity; stage B indicates that it involves only the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses; and stage C indicates that it extends beyond the stage B limits. The staging system proposed by Dulguerov employs the tumor-node-metastasis classii cation(3,4).

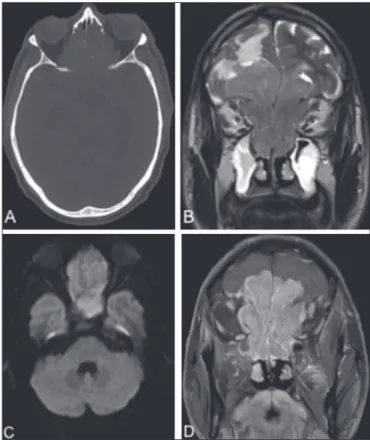

Bone destruction and calcii cation within the lesion can be characterized by CT(5). An MRI scan provides more accurate information on the extent of the tumor, especially in terms of intracranial and orbital involvement. On MRI, the majority of olfactory neuroblastomas present a signal that is (in relation to that of muscle tissue) hypointense in T1-weighted sequences

and hyperintense in T2-weighted sequences, as well as showing intense enhancement in contrast-enhanced sequences(6,7). MRI is also superior to CT in the evaluation of recurrence after cra-niofacial resection, because of its greater ability to differentiate i brous scar tissue from residual or recurring neoplasia(6). Cysts in the intracranial margin of the tumor have been reported in cases of olfactory neuroblastoma. Another relevant aspect is a dumbbell-like morphology, the tumor mass being divided be-tween the anterior cranial fossa and the nasal cavity, the cribri-form plate cribri-forming the “waist”(5).

The main differential diagnoses of olfactory neuroblastoma include: squamous cell carcinoma, typically in the maxillary an-trum, with bone erosion; sinonasal adenocarcinoma, with het-erogeneous enhancement, which has been associated with occu-pational exposure to wood dust; undifferentiated sinonasal carci-noma, which affects older patients; and dural-based invasive me-ningioma, with poorly dei ned borders and areas of necrosis(8).

REFERENCES

1. Ferreira MCF, Tonoli C, Varoni ACC, et al. Estesioneuroblastoma. Rev

Ciênc Méd. 2007;16:193–8.

2. Howell MC, Branstetter BF 4th, Snyderman CH. Patterns of regional spread for esthesioneuroblastoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:929–

33.

3. Van Gompel JJ, Giannini C, Olsen KD, et al. Long-term outcome of esthe-sioneuroblastoma: Hyams grade predicts patient survival. J Neurol Surg B

Skull Base. 2012;73:331–6.

4. Tajudeen BA, Arshi A, Suh JD, et al. Importance of tumor grade in

esthe-sioneuroblastoma survival: a population-based analysis. JAMA

Otolaryn-gol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140:1124–9.

5. Mendonça VF, Carvalho ACP, Freitas E, et al. Tumores malignos da cavi-dade nasal: avaliação por tomograi a computadorizada. Radiol Bras. 2005;

38:175–80.

6. Li C, Yousem DM, Hayden RE, et al. Olfactory neuroblastoma: MR evalu-ation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1993;14:1167–71.

7. Schuster JJ, Phillips CD, Levine PA. MR of esthesioneuroblastoma (olfac-tory neuroblastoma) and appearance after craniofacial resection. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:1169–77.

8. Baptista AC, Marchiori E, Boasquevisque E, et al. Comprometimento

órbito-craniano por tumores malignos sinonasais: estudo por tomograi a

computadorizada. Radiol Bras. 2002;35:277–85. Figure 1. CT of the brain (A), with a bone window, showing an expansile lesion

occupying ethmoid cells and containing calcii cations, with bone destruction.

MRI demonstrated that the lesion was extra-axial, with lobulated contours, lo-cated in the upper portion of the nasal cavity, and extended to the anterior cranial fossa, facial sinuses, and orbits. A coronal T2-weighted sequence (B) shows that the expansile lesion presented an isointense signal, although a hyperintense signal (edema) can be seen in the brain parenchyma in the fron-tal lobe, mainly on the left. An axial diffusion-weighted imaging sequence (C) shows a hyperintense signal (restricted diffusion). A contrast-enhanced coronal T1-weighted sequence (D) shows intense enhancement.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0100-3984.2015.0206

Giant ovarian teratoma: an important differential diagnosis of pelvic mas-ses in children

Dear Editor,

An 8-year-old female patient presented with diffuse ab-dominal pain accompanied by progressive distension. Physical examination revealed a large abdominal mass, predominantly in the mesogastrium, that was depressible and painless on palpa-tion. Ultrasound showed a solid-cystic formation extending from the epigastrium to the hypogastrium, with a calcium component and an air-l uid level (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) showed a massive solid-cystic formation, with a fat component and soft tissue, as well as calcii cations, measuring 12.6 × 19.2

× 20.8 cm, exerting a signii cant mass effect, displacing the small intestine, aorta, and inferior vena cava, as well as causing slight compression of the pancreas, kidneys, and ureters, with no apparent signs of ini ltration (Figure 2). Intraoperatively, the mass was seen to be adhered to the left fallopian tube and to the greater omentum (Figure 1). The tumor was excised without complications, and the patient was discharged i ve days later. A follow-up abdominal ultrasound revealed no changes.

343

Radiol Bras. 2017 Set/Out;50(5):338–348Letters to the Editor

Felipe Nunes Figueiras1, Márcio Luís Duarte2, Élcio Roberto Duarte1, Daniela Brasil Solorzano1, Jael Brasil de Alcântara Ferreira1

1. Santa Casa de Santos – Radiologia, Santos, SP, Brazil. 2. Hospital São Camilo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Mailing address: Dr. Felipe Nunes Figueiras. Santa Casa de Santos – Radiologia. Avenida Doutor Cláudio Luís da Costa, 50, Jabaquara. Santos, SP, Brazil, 11075-900. E-mail: bilita88@gmail.com.

Ovarian teratoma is the most prevalent germ cell neoplasm, accounting for approximately 32% of all ovarian neoplasms, and can be divided into mature or immature teratoma depending on its cellular differentiation(1). The cellular components of this lesion are pronounced and varied, potentially encompass-ing respiratory epithelium, skin, cartilage, mucosa, and neural epithelium(2–5). It is a benign neoplasm, presenting on physi-cal examination as a palpable pelvic mass, typiphysi-cally 5–10 cm in diameter, and occurs bilaterally in 10–15% of cases(1). In 10% of cases, it is considered an emergency, presenting the typical proile of acute abdomen, due to torsion of the vascular pedicle that occurs secondary to its growth(6). The clinical diagnoses of abdominal masses are diverse and imprecise, requiring comple-mentary diagnostic imaging(7).

Abdominal X-ray is nonspeciic for ovarian teratoma and can occasionally show calciications in the area surrounding the lesion. Ultrasound and CT are the main imaging methods for the detection of this disease, the rapid detection of which de-mands recognition of the typical imaging patterns, particularly in cases of emergency (acute onset). Although CT also has high speciicity and sensitivity, particularly for the detection of cys -tic teratoma, it is not routinely employed, because it involves the use of ionizing radiation. The combination of various im-aging methods is an essential part of the surgical planning(8). The histological study is also of importance, determining the macroscopic and microscopic aspect of the lesion, as well as the prognosis. Surgical treatment—excision of the lesion—is the gold standard(8).

REFERENCES

1. Wu RT, Torng PL, Chang DY, et al. Mature cystic teratoma of the ovary:

a clinicopathologic study of 283 cases. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 1996;58:269–74.

2. Akbulut M, Zekioglu O, Terek MC, et al. Florid vascular proliferation in mature cystic teratoma of the ovary: case report and review of the litera-ture. Tumori. 2009;95:104–7.

3. Baker PM, Rosai J, Young RH. Ovarian teratomas with lorid benign vas

-cular proliferation: a distinctive inding associated with the neural com -ponent of teratomas that may be confused with a vascular neoplasm. Int

J Gynecol Pathol. 2002;21:16–21.

4. Nogales FF, Aguilar D. Florid vascular proliferation in grade 0 glial

im-plants from ovarian immature teratoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2002;21:

305–7.

5. Fellegara G, Young RH, Kuhn E, et al. Ovarian mature cystic teratoma with lorid vascular proliferation and Wagner-Meissner–like corpuscles. Int J Surg Pathol. 2008;16:320–3.

6. Stuart GC, Smith JP. Ruptured benign cystic teratomas mimicking gyne -cologic malignancy. Gynecol Oncol. 1983;16:139–43.

7. Mahaffey SM, Ryckman FC, Martin LW. Clinical aspects of abdominal masses in children. Semin Roentgenol. 1988;23:161–74.

8. Buy JN, Ghossain MA, Moss AA, et-al. Cystic teratoma of the ovary: CT

detection. Radiology. 1989;171:697–701.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0100-3984.2016.0026 Figure 1. A: Ultrasound of the

abdo-men, showing a massive solid-cystic formation with a pronounced solid component (arrow). B: Intraopera-tive photograph showing the large volume of the lesion and its

encap-sulated appearance.

A

B

Figure 2. A: Non-contrast-enhanced axial CT scan showing an extensive solid-cystic formation, with a fatty component, a liquid component,

and calciications. B: Intravenous contrast-enhanced axial CT scan showing a compressive effect on and displacement of the structures adjacent to the lesion—the pan-creas, abdominal aorta, inferior vena cava, small intestine, and left

kidney.