www.jped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Serum

phenylalanine

in

preterm

newborns

fed

different

diets

of

human

milk

夽

,

夽夽

Débora

M.

Thomaz

a,

Paula

O.

Serafin

a,

Durval

B.

Palhares

a,b,

Luciana

V.M.

Tavares

a,c,

Thayana

R.S.

Grance

a,∗aUniversidadeFederaldeMatoGrossodoSul(UFMS),CampoGrande,MS,Brazil bCaseWesternReserveUniversity-RBCH,Cleveland,UnitedStates

cUniversidadeCatólicaDomBosco(UCDB),CampoGrande,MS,Brazil

Received20June2013;accepted10February2014

Availableonline10May2014

KEYWORDS

Serumphenylalanine; Humanmilk;

Humanmilkfortifier; Bankedhumanmilk; Pretermnewborns

Abstract

Objective: Toevaluatephenylalanineplasmaprofileinpretermnewbornsfeddifferenthuman milkdiets.

Methods: Twenty-fourvery-lowweightpretermnewbornsweredistributedrandomlyinthree groups withdifferentfeedingtypes:Group I:bankedhumanmilk plus5% commercial forti-fierwithbovineprotein,GroupII:bankedhumanmilkplusevaporatedfortifierderivedfrom modifiedhumanmilk,GroupIII:bankedhumanmilkpluslyophilizedfortifierderivedfrom mod-ifiedhumanmilk.Thenewbornsreceivedthegroupdietwhenfulldietwasattainedat15±2 days.Plasmaaminoacidanalysiswasperformedonthefirstandlastdayoffeeding.Comparison amonggroupswasperformedbystatisticaltests:onewayANOVAwithTukey’spost-testusing SPSSsoftware,version20.0(IBMCorp,NY,USA),consideringasignificancelevelof5%. Results: Phenylalaninelevelsinthefirstandsecondanalysis were,respectively,inGroup I: 11.9±1.22and29.72±0.73;inGroupII:11.72±1.04and13.44±0.61;andinGroupIII:11.3 ±1.18and15.42±0.83mol/L.

Conclusion: Theobservedresultsdemonstratedthathumanmilkwithfortifiers derivedfrom humanmilkactedasagoodsubstratumforpreterminfantfeedingbothintheevaporatedor thelyophilizedform,withoutsignificantincreasesinplasmaphenylalaninelevelsincomparison tohumanmilkwithcommercialfortifier.

©2014SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

夽 Pleasecitethisarticleas:ThomazDM,SerafinPO,PalharesDB,TavaresLV,GranceTR.Serumphenylalanineinpretermnewbornsfed

differentdietsofhumanmilk.JPediatr(RioJ).2014;90:518---22.

夽夽

StudyperformedatUniversidadeFederaldeMatoGrossodoSul,CampoGrande,MS,Brazil.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:thayanagrance@yahoo.com(T.R.S.Grance).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2014.02.003

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Fenilalanina plasmática; Leitehumano; Aditivoparaleite humano;

Leitehumanode banco;

Recém-nascido pré-termo

Fenilalaninaplasmáticaemrecém-nascidospré-termoalimentadoscomdiferentes dietasdeleitehumano

Resumo

Objetivo: Avaliaroperfilplasmáticodoaminoácidofenilalaninaemrecém-nascidospré-termo alimentadoscomdiferentesdietasdeleitehumano.

Métodos: Foramestudados24recém-nascidospré-termodemuitobaixopeso,distribuídosem trêsgruposcomdiferentesdietas:GrupoI:leitehumanodebancocom5%deaditivocomercial paraleitehumanocomproteínadeorigembovina(LHB-AC);GrupoII:leitehumanodebanco comaditivodeleitehumanomodificadoevaporado(LHB-E);eGrupoIII:leitehumanodebanco comaditivodeleite humanomodificadoliofilizado(LHB-L). Osrecém-nascidosreceberam a dietadefinidaparaogrupoquandoalcanc¸aramdietaplenapor15±2dias.Aanálisedo aminoá-cidoplasmáticofoifeitanoprimeiroeúltimodiasdadieta.Acomparac¸ãoentreosgruposfoi realizadapormeiodotesteANOVAdeumavia,seguidopelopós-testedeTukey,utilizando-seo softwareSPSS,versão20.0(IBMCorp,NY,EUA),econsiderandoumníveldesignificânciade5%. Resultados: Asconcentrac¸õesplasmáticasdoaminoácidofenilalaninanaprimeira esegunda análisesforam, respectivamente,noGrupo I(LHB-AC)11,9±1,22e29,72±0,73;noGrupoII (LHB-E)11,72±1,04e13,44±0,61;enoGrupoIII11,3±1,18e15,42±0,83umol/L.

Conclusão: Osresultadosencontradosdemonstramqueoleitehumanocomaditivosdopróprio leitehumanocomportou-secomoumbomsubstratoparaalimentac¸ãodorecém-nascido pré-termo, tanto naforma evaporada como liofilizada, sem levara aumentos significativos na concentrac¸ão plasmática de fenilalanina em comparac¸ão ao leite humano comaditivo co-mercial.

©2014SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Todososdireitos reservados.

Introduction

The superiority of human milk (HM) feeding in preterm newborns (PNs) is well documented. HM has an impor-tantimpactonbraingrowthanddevelopment,evenwhen it does not promote great weight gain, supporting the conceptthattheoptimalpostnatalgrowthofPNsisnotyet known.1---5

Regarding thesupplyof proteins,notonlythequantity but also the quality is important for proper growth. The aminoacidcompositionofformulasandadditivestohuman milkusingbovineproteinhasreducedqualityinrelationto HM,6---9whichisconsideredthegoldstandard.

The protein fraction of cow’s milk has a predomi-nance of casein, which has high content of the amino acidphenylalanine.10 Althoughitisanessentialaminoacid in children receiving cow’s milkprotein, plasma levelsof this amino acid are high (close to those associated with metabolismdefects).11---13

The increased intake and plasma levels of phenylala-nine results in the inhibition of the enzyme tyrosinase, andsubsequentconversion,throughhydroxylation,of phen-ylalanine into tyrosine, increasing tyrosine availability. This increase can cause a deleterious effect on brain development,leadingtoconsequencessuchassleep distur-bance, memory deficits, and attention and concentration deficits.14---17

WhiletheoptimalnutritionforPNsisunknown, neona-tologists should be committed to what appears to be ideal,whichdoes notresultinchangesin theshort-term, and provides better long-term development. In this con-text, supplementing HM with an additive containing a

proteinhomologoustothatofHMappearstobeasuitable alternativeforproteinsupply,whilemaintainingsafeplasma levelsofphenylalanine.18---20

Considering this hypothesis, this study aimed to com-paratively analyze plasma levels of phenylalanine in PNs fedbankedhumanmilk(BHM)plusthecommercialadditive FM85(FortifiedMilk 85,Nestlé,SãoPaulo, Brazil)andPNs fedwithBHMplusan additivederivedfromtheHMitself, afterremovaloffatandlactoseinevaporatedorlyophilized forms.

Methods

AfterapprovaloftheFederalUniversityofMatoGrossodo Sul (UFMS) Research Ethics Committee (Res. 17/2006), a non-blindedrandomizedclinical trial wasperformed from 2008to2010,intheneonatologysectionof theNúcleodo HospitalUniversitário(NHU)ofUFMS(UniversidadeFederal deMatoGrossodoSul,CampoGrande,MS,Brazil).

Atotalof24PNshospitalizedintheneonatalsector,of bothgenders,werestudied afterbeingdivided intothree groups.EachgroupreceivedadifferentHM-baseddiet.The groupswerecomparedfor plasmalevelsofphenylalanine. Toconfirm thatthe groupshad similarcharacteristicsand thatthedifferenceinplasmaphenylalaninelevelswas asso-ciatedwiththediettheyreceived,thePNswerecompared regardinggender, gestationalweight/age, respiratory dis-tresssyndrome(RDS),gestationalage,birthweight,startof feeding,volume,calories,earlyminimalenteralnutrition, anddaysonventilator.

GroupI:PNsfedBHM,plus5%commercialadditiveFM85®

(Nestlé,SãoPaulo,Brazil),identifiedbytheacronym: BHM-CA;

Group II: PNs fed BHM with modified HM supplement: 100mLof skimmed HM,evaporated at 20%,withlactose extractionandadded80mLofpasteurizedHM,identified bytheacronym:BHM-E;

Group III: PNs fed BHM, with modified HM supplement: 70mL of skimmed HM, evaporated at 20%, with lactose extraction,lyophilized,reconstitutedin100mLofBHMand pasteurized,identifiedbytheacronym:BHM-L.

TheadditivesobtainedfromHMwerepreparedaccording tothemethoddescribedbyThomasetal.21

Ofthe24PNs, tenbelongedtoGI,fivetoGII,andnine toGIII.They werefedaccording tothisorderatdifferent times.Althoughselectionwasnotblinded,allPNswhomet theinclusioncriteriaandwhowerehospitalizedduringthe studyperiodinNHU-UFMSwereselectedforthestudy.

The PNsincluded inthestudyhadgestationalage<34 weeks;birthweight≤1.500kg,whetherornotadequatefor gestationalage; were clinically stable;had nocongenital malformations;andtheirparents,afterbeinginformedof thenatureofthestudy,signedtheinformedconsent.

PNs were excluded from the study in the presence of congenitalmalformations,metabolicdisorders,anemia,any activedisease(respiratorydisorders,centralnervoussystem manifestationsand gastrointestinal), periventricular hem-orrhage≥grade2,andthosewhosemothershadsufficient milkforfeeding.

Duringthestudy,PNsthatpresentedunfavorable condi-tionsfortheresearchdevelopmentweresubstituted;these conditionswere utterly related toworsening of infection level.

ThePNsstartedreceivingthespecificdietofthegroup theybelongedtoonlywhentheyreachedfull(100mL/kg) andwell-toleratedenteraldietand,therefore,thePNswere enrolledinthestudyassoonastheystartedenteralfeeding bygavage.

The PNswere followedsincethey startedreceivingthe modifiedmilkfor15±2days.

Non-blinded analysisof levelsof the aminoacid phen-ylalanine in plasma was performed. For the analysis, a pre-prandial venous sample was collected (2.5 to3hours after the last feeding) by percutaneous puncture with a syringe containing three drops of heparin (anticoagulant effect),packagedinamicrofugetube(EppendorfdoBrasil Ltda, São Paulo, Brazil).The plasma was then separated by centrifugation (2,500rpm for 10min), identified, and frozenat-20◦Cforsubsequentaminoacidanalysisbyhigh

performance liquid chromatography. Blood collection was performed in each child ofthe threegroups for compari-sonof the aminoacid profile onthe first day, beforethe newborns started thespecific group diet, andon thelast daytheyreceivedthisdiet.

The evaluation of the association between diets offeredto the PNswith the variables gender, gestational weight/age,andRDSwasperformed usingthechi-squared test.TheassociationbetweendietsofferedtothePNsand thevariablesgestationalage,birth weight,earlyfeeding, volume,calories,early minimal enteralnutrition, daysof

Plasma phen

ylalanine le

vels (

µ

mol/L)

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

1 15

Moment (days)

BHM-CA

BHM-E

BHM-L

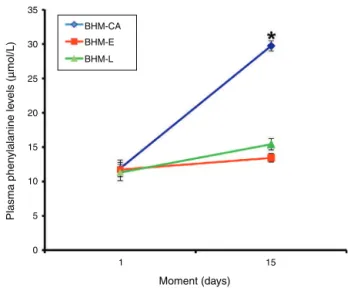

Figure1 Chart showingserumphenylalanine levelsineach ofthePNfeedingregimensusedinthisstudyandaccordingto thetimeofanalysis.Eachsymbolrepresentsthemeanandthe barrepresentsthestandarderrorofthemean.

mechanicalventilation,andplasmalevelsofphenylalanine wasperformedbyone-wayANOVA,followedbyTukey’s post-test. The results of the other variables assessed in this studywereshownasdescriptivestatisticsorintablesand charts. Statisticalanalysis wasperformedusing SPSS soft-wareprogram,release20.0(IBMCorp,NY,USA),considering asignificancelevelof5%.

Results

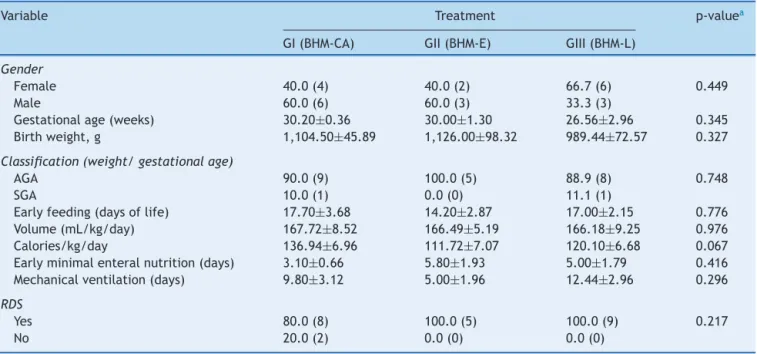

The characteristics of the three groups regarding gender, gestational age,birth weight,adequate weightfor gesta-tionalage,earlyminimalenteralfeeding,earlyfullenteral feeding,useofmechanicalventilation,respiratorydistress syndrome,meanvolume,andcaloriesreceivedinthedaily dietareshowninTable1.

Regarding thesecharacteristics, the groups showed no significantdifferences(Table1).

Plasmalevelsoftheaminoacidphenylalanine(mean± SEM)inthefirstandsecondanalysiswere,respectively:11.9 ±1.22and29.72±0.73mol/LinGroupI(BHM-CA);11.72

± 1.04and 13.44± 0.61mol/L inGroup II (BHM-E);and

11.3 ± 1.18 and 15.42 ± 0.83mol/L in Group III

(BHM-L).Theresultsregardingtheconcentrationoftheessential aminoacidphenylalaninein GroupsI,II,andIIIareshown inFig.1.

Table1 Resultsforthevariablesassessedinthisstudy,accordingtothefeedingtypeofferedtopretermnewborns.

Variable Treatment p-valuea

GI(BHM-CA) GII(BHM-E) GIII(BHM-L)

Gender

Female 40.0(4) 40.0(2) 66.7(6) 0.449

Male 60.0(6) 60.0(3) 33.3(3)

Gestationalage(weeks) 30.20±0.36 30.00±1.30 26.56±2.96 0.345 Birthweight,g 1,104.50±45.89 1,126.00±98.32 989.44±72.57 0.327

Classification(weight/gestationalage)

AGA 90.0(9) 100.0(5) 88.9(8) 0.748

SGA 10.0(1) 0.0(0) 11.1(1)

Earlyfeeding(daysoflife) 17.70±3.68 14.20±2.87 17.00±2.15 0.776 Volume(mL/kg/day) 167.72±8.52 166.49±5.19 166.18±9.25 0.976 Calories/kg/day 136.94±6.96 111.72±7.07 120.10±6.68 0.067 Earlyminimalenteralnutrition(days) 3.10±0.66 5.80±1.93 5.00±1.79 0.416 Mechanicalventilation(days) 9.80±3.12 5.00±1.96 12.44±2.96 0.296

RDS

Yes 80.0(8) 100.0(5) 100.0(9) 0.217

No 20.0(2) 0.0(0) 0.0(0)

Theresultsareshownasmean±standarderrorofthemeanorrelativefrequency(absolutefrequency). RDS,respiratorydistresssyndrome;AGA,appropriateforgestationalage;SGA,smallforgestationalage.

a p-valueintheone-wayANOVA(gestationalage,birthweight,startoffeeding,volume,calories,startofminimalenteralnutrition,

andmechanicalventilation)orchi-squaredtest(gender,weight/gestationalageclassification,RDS).

Discussion

It is suggested that blood samples should be collected immediatelybeforefeedingwhenanalyzingtheaminoacid profile,sotheycanbeanalyzedwithlessinterferencefrom thedietoffered.Thisevidencejustifiesthechoiceof per-formingthepre-prandialcollectionofbloodforaminoacid analysis.22

WhenphenylalaninelevelswerecomparedbetweenPNs feddifferentdiets,itwasobservedthatthosefed commer-cialadditiveshadhigherplasmalevelsofthisaminoacid, witha significant differencewhencomparedto thosefed theevaporatedandlyophilizedadditives.

Considering thatthe groups weresimilarregarding the characteristicsshowninTable1andthattheplasma phen-ylalaninelevelsweresimilarinthethreegroupsatbaseline, this difference in phenylalanine levels at the end of the studyseemstoberelatedtothequalityoftheproteinin theadditiveusedbyeachgroupandthelowerdegradation capacity of thisamino acid in PNscompared tofull-term newborns. Thedifferenceshouldnotbe associatedtothe total amount of protein consumed, as the mean protein contentofthedietintheBHM-CAgroup(1.96±0.01g/dL) isintermediatetothoseingroupsBHM-E(1.81±0.01g/dL) andBHM-L(2.38±0.03g/dL).21

Although the caloric value of BHM-CA (81.65 ± 0.87kcal/dL) is greater than that of BHM-E (67.78 ± 2.01kcal/dL) and BHM-L (72.27 ± 2.56kcal/dL), a still unpublishedclinicalstudyobservedthatweightandlength gainwassimilarinthethreegroups,withtheadvantageof increasedheadcircumferenceintheBHM-Lgroupinrelation totheothers.21Thesegrowthcharacteristicsshowthegood useofproteinofferedbyhomologousadditivesin compari-sontothecommonlyusedcommercialadditive.

Studies evaluatingthe amino acid blood profile of PNs fedHMwiththecommercialadditiveFM85®observedthat betteradequacyoftheproteinsuppliedbythissupplement isnecessary.Theadditiveofheterologousoriginresultedin biochemicalmacronutrient alterationsthat mayaffect the children’sneurodevelopment.23,24

When analyzing plasma phenylalanine levels in groups of healthy newborns at 6 months fed breast milk, regu-larformula,twotypesofformulaswithhydrolyzedcasein, andformulaswithhydrolyzedwheyprotein,thegroupfed breastmilkhadthelowestlevelsoftheaminoacid,25which appears tooccur evenin full-term newborns, due tothe highercontentofphenylalanineinformulasbasedoncow’s milk.

ThesameresultwasfoundinPNsfedHMwiththree dif-ferentadditives:HMprotein,cow’smilkwheyprotein,and amixtureofcow’smilkwheyprotein,peptides,andamino acids,withanaminoacidcompositionsimilartothatofHM. Phenylalaninelevelswerehigherinthegroupwhoreceived HMwithcow’s milkwhey proteinadditive.The other two groupsshowednodifferences.26

Additionally,inPNsgroupedaccordingtogestationalage andfedHMorfourtypesofformulawithproteinextracted fromcow’smilkwithdifferentlevelsandproportionofwhey protein/casein,thosefedHMshowedlowerplasmalevelsof phenylalanine.27

Conversely, astudy that offeredPNsBHM,BHM evapo-ratedat70%,or BHMwiththecommercialadditiveFM85® foundnosignificantdifferencesinplasmalevelsof phenyl-alanine.Inthiscase,neitherthequantitynorthequalityof proteinofferedhadaneffectonserumlevelsofthisamino acid.23

enteralnutritionobservedthattheconcentrationsofglycine is moreaffected by the route of administration, whereas leucineislittleaffected,andphenylalanineismoreaffected bytheofferedsupply.28

Despitethesignificantincreaseinplasmaphenylalanine, nosignificantmetaboliceffectswereobservedinbabiesfed bovineproteinduringthestudy;however,inthelongterm,it canbeanegativefactorforcognitivedevelopment. There-fore,theoptimalplasmalevelsofphenylalanineinorderto avoideffectsoncognitivedevelopmentinthelongtermare stillquestioned.

ThisinvestigationdemonstratedthattheHMwithitsown additivesactedasagoodsubstratetofeedPNs,whetherin theevaporatedorlyophilizedforms,withoutleadingto sig-nificantincreasesinplasmaphenylalaninewhencompared toHMwithcommercialadditive.

Funding

ResearchgrantfromFundac¸ãodeApoioaoDesenvolvimento doEnsino,CiênciaeTecnologiadoEstadodeMatoGrossodo Sul(FUNDECT).

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.CockerillJ,UthayaS,DoréCJ,ModiN.Acceleratedpostnatal headgrowthfollowspretermbirth.ArchChildFetalNeonatal. 2006;1:184---7.

2.SinghalA,FarooqiIS,O’RahillyS,ColeTJ,FewtrellM,LucasA. Earlynutritionandleptinconcentrationinlaterlife.AmJClin Nutr.2002;75:993---9.

3.SinghalA, FewtrellM,ColeTJ,LucasA. Lownutrientintake andearlygrowthforlaterinsulinresistanceinadolescentsborn preterm.Lancet.2003;361:1089---97.

4.HalesCN,OzanneSE.Thedangerousroadofcatch-upgrowth. JPhysiol.2003;547:5---10.

5.ChanGM,LeeML,RechtmanDJ.Effectsofahumanmilk-derived humanmilkfortifierontheantibacterialactionsofhumanmilk. BreastfeedMed.2007;2:205---8.

6.MartinezFE,CameloJuniorJS.Alimentac¸ãodorecém-nascido pré-termo.JPediatr(RioJ).2001;77:32---40.

7.PalharesDB,JorgeSM,Gonc¸alvesAL,MartinezFE.Aminoácidos plasmáticosderecémnascidospré-termoalimentadoscomleite humanodebancodeleiteoufórmuladosleitedevaca.JPediatr (RioJ).1990;66:188---92.

8.LucasA.Influenceofneonatalnutritiononlong-termoutcome. In:SalleBL,SwyerPR,editors.Nutritionofthe very-low-birth-weightinfant.NestléNutritionWorkshopSeries,32.NewYork: RavenPress;1993.p.183---96.

9.PereiraGR,NiemanL.Métodosdenutric¸ãoporviaenteralem recém-nascidopré-termo.In:PereiraGR,LeoneCR,Navantino AF,editors.TrindadeOF.Nutric¸ãodorecém-nascidopré-termo. RiodeJaneiro:Medbook;2008.p.31---43.

10.PencharzPB,BallRO.Aminoacidneedsforearlygrowthand development.JNutr.2004;134:1566---8.

11.Räihä NC. Biochemical basis for nutritional management of preterminfants.Pediatrics.1974;53:147---56.

12.HayJrWW.Strategiesforfeedingthepreterminfant. Neona-tology.2008;94:245---54.

13.Vaz FA, Lauridsen E, Troster EJ. Alimentac¸ão do recém-nascido pré-termo: considerac¸ões atuais. Pediatria. 1985;7: 3---7.

14.Cie´slaJ,Fr˛aczykT,RodeW.Phosphorylationofbasicaminoacid residuesinproteins:importantbuteasilymissed.ActaBiochim Pol.2011;58:137---48.

15.KilaniAR,ColeFS,BierDM.Phenylalaninehydroxylaseactivity inpreterminfants:istyrosineaconditionallyessentialamino acid?AmJClinNutr.1995;61:1218---23.

16.Denne SC, Karn CA, Ahlrichs JA, Dorotheo AR, Wang Juny-ing,LiechtyEA.Proteolysisandphenylalaninehydroxylationin responsetoparenteralnutritioninextremely prematureand normalnewborns.JClinInvest.1996;97:746---54.

17.ShortlandGJ, Walter JH, FlemingPJ, Halliday D. Phenylala-ninekineticsinsickpretermneonateswithrespiratorydistress syndrome.PediatrRes.1994;36:713---8.

18.LucasA,LucasPJ,ChavinSI,LysterRL,BaumJD.Ahumanmilk formula.EarlyHumDev.1980;4:15---21.

19.SantosMM, Martinez FE, Sieber VM, Pinhata MM, Ferlin ML. Acceptability and growth of VLBW --- infants fed with own mother’milkenrichedwithanaturalorcommercialhumanmilk fortifier.PediatricResearch.1997;41:231.

20.Camelo Junior JS, Martinez FE. Lactoengenharia do leite humano.In:PereiraGR,LeoneCR,AlvesFilhoN,TrindadeFilho O,editors.Nutric¸ãodorecém-nascidopré-termo.São Paulo: Medbook;2008.p.11---29.

21.ThomazDM, Serafim PO, PalharesDB, MelnikovP, Venhofen L, Vargas MO. Comparison between homologous human milk supplementsandacommercialsupplementforverylowbirth weightinfants.JPediatr(RioJ).2012;88:119---24.

22.Graham-ThiersPM,BowenLK.Effectofproteinsourcenitrogen balanceand plasmaaminoacidsinexercisinghorses.JAnim Sci.2011;89:729---35.

23.SantosSC, Figueiredo CM, Andrade SM,PalharesDB. Plasma amino acids in preterm infants fed different human milk diets from a human milk bank. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;2: 51---6.

24.PalharesDB, ThomazDM,TavaresLV,SerafinP.Effectofdiet onserumaminoacidprofileinvery-low-birthweightneonates. AdvancesinMedicineandBiology.2011:31.

25.Olle H, Lõnnerdal BO. Nutritional evaluation of protein hydrolysate formulasin healthy term infants: plasmaamino acids,hematology,and traceelements.AmericanJClinNutr. 2003;78:296---301.

26.Boehm G, Borte M, Bellstedt K, Moro G, Minoli I. Protein quality of human milk fortifier in low birth weight infants: effectsongrowthandplasmaaminoacidprofiles.EurJPediatr. 1993;152:1036---9.

27.RassinDK,GaullGE,RaihäNC,HeinonenK.Milkprotein quan-tity and quality in low-birth weight infants: IV: Effects on tyrosine and phenylalanine in plasma and urine. J Pediatr. 1977;90:356---60.