www.jped.com.br

REVIEW

ARTICLE

Current

knowledge

of

environmental

exposure

in

children

during

the

sensitive

developmental

periods

夽

Norma

Helena

Perlroth

a,b,∗,

Christina

Wyss

Castelo

Branco

a,caUniversidadeFederaldoEstadodoRiodeJaneiro(UNIRIO),ProgramadePós-Graduac¸ãoemEnfermagemeBiociências,Riode

Janeiro,RJ,Brazil

bUniversidadeFederaldoEstadodoRiodeJaneiro(UNIRIO),DepartamentodeMedicinaGeral/Pediatria,RiodeJaneiro,RJ,

Brazil

cUniversidadeFederaldoEstadodoRiodeJaneiro(UNIRIO),DepartamentodeCiênciasNaturais,RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil

Received10July2016;accepted19July2016 Availableonline4November2016

KEYWORDS

Children’shealth; Environmental exposure; Vulnerability; Pathwaysoftoxicity penetration; Developmental disability

Abstract

Objective: Thisstudyaimstoidentifythescientificevidenceontherisksandeffectsofexposure

toenvironmentalcontaminantsinchildrenduringsensitivedevelopmentalperiods.

Datasource:Thesearchwas performedintheBiremedatabase,usingtheterms:children’s

health, environmental exposure, health vulnerability,toxicity pathways and developmental

disabilitiesintheLILACS,MEDLINEandSciELOsystems.

Datasynthesis: Childrendifferfromadultsintheiruniquephysiologicalandbehavioral

char-acteristicsandthepotentialexposuretoriskscausedbyseveralthreatsintheenvironment.

Exposuretotoxicagentsisanalyzedthroughtoxicokineticprocessesintheseveralsystemsand

organsduringthesensitivephasesofchilddevelopment.Thecausedeffectsarereflectedin

theincreasedprevalenceofcongenitalmalformations,diarrhea,asthma,cancer,endocrineand

neurologicaldisorders,amongothers,withnegativeimpactsthroughoutadultlife.

Conclusion: Toidentifythecausesandunderstandthemechanismsinvolvedinthegenesisof

these diseasesisachallengefor science,asthereisstillalackofknowledgeonchildren’s

夽

Please citethisarticleas:Perlroth NH,BrancoCW.Currentknowledgeofenvironmental exposureinchildrenduringthesensitive developmentalperiods.JPediatr(RioJ).2017;93:17---27.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:norma.perlroth@gmail.com(N.H.Perlroth).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2016.07.002

susceptibilitytomanyenvironmentalcontaminants.Preventionpoliciesandmoreresearchon

childenvironmentalhealth,improvingtherecordingandsurveillanceofenvironmentalrisksto

children’shealth,shouldbeanongoingpriorityinthepublichealthfield.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen

accessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/

4.0/).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Saúdeinfantil; Exposic¸ãoambiental; Vulnerabilidade; Viasdepenetrac¸ão datoxicidade; Deficiênciasdo desenvolvimento

Oestadoatualdoconhecimentosobreaexposic¸ãoambientalnoorganismoinfantil duranteosperíodossensíveisdedesenvolvimento

Resumo

Objetivo: Opresenteestudobuscaidentificarasevidênciascientíficassobreosriscoseefeitos

daexposic¸ãodecontaminantesambientaisnoorganismoinfantilduranteosperíodossensíveis

deseudesenvolvimento.

Fontededados: Aspesquisasforamrealizadas pelobancode dadosdaBireme,comos

ter-moschildren’s health, environmental exposure,health vulnerability, toxicity pathways and

developmentaldisabilitiesnossistemasLILACS,MEDLINEeSciELO.

Síntesededados: Acrianc¸adiferedoadultoporsuascaracterísticassingularesdeordem

fisi-ológica,comportamentaledopotencialdeexposic¸ãoariscosfrente àsdiversasameac¸asdo

ambiente. A exposic¸ão a agentes tóxicos é analisada por meio dos processos

toxicocinéti-cosnosdiversossistemaseórgãosduranteasjanelassensíveisdodesenvolvimentoinfantil.

Osefeitos causadostransparecemnoaumento daprevalênciademalformac¸ões congênitas,

diarreia, asma,cânceres,distúrbios endócrinoseneurológicos, entreoutros, comimpactos

negativosaolongodavidaadulta.

Conclusão: Identificarascausasecompreender osmecanismosenvolvidosnagênese desses

agravoséumdesafioqueseimpõeàciência,vistoqueaindaháumalacunadeconhecimento

sobreasuscetibilidadeinfantilparamuitoscontaminantesambientais.Políticasdeprevenc¸ãoe

maispesquisasemsaúdeambientalinfantil,queimpulsionemoregistroeavigilância

epidemi-ológicadosriscosambientaisàsaúdedacrianc¸a,deveserumaprioridadecontínuanocampo

dasaúdepública.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigo

OpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.

0/).

Introduction

In1946,theWorldHealthOrganizationdeclared,inanopen lettertoitsmembers,thatallchildrenhavetherighttoa healthydevelopmentwheretheycanliveharmoniouslyina diversifiedenvironment1sothat,inanearfuture,theycan

reachtheirfullpotentialasworldcitizens.2Fromabroader

view,itcanbesuggestedthatthisconceptofenvironment includes notonly thenatural world,but alsothe physical contextinwhichthechildinteractswithitsworld:the exter-nalenvironment (air,water,earth, andliving beings);the community(social environment,school,andneighborhood wherethechildlives);andthehomeenvironment.3

The interest and the degree of knowledge about the differentwaysinwhichtheenvironmentcaninfluence chil-dren’s health in the places where they routinely stay in theirdaily life has increasedconsiderablyin the last two decades.2 They include not only the child asa biological

beingwithageneticpotential,butalsotheinteractionofa multitudeofinfluences(physical,chemical,andbiological), as well as factors (psychosocial, cultural, and economic) thathaveacompleximpactonthelifeofthesechildren.4---7

Children comprise 26% of the world’s population and are among the most vulnerable groups to be exposed to

environmental risks.It is estimatedthat theyaccountfor over30%(31---40%)oftheglobaldiseaseburden,especially in childrenunder 5yearsof age.8,9 Consideringthis

terri-blepicture,ofacompletelyimbalancedstatebetweenthe childanditsenvironment,thereisapopulationof223 mil-lion young citizens who,over the past twodecades, died beforereachingtheageof5years.10

Unhealthy environments, unfavorable situations regarding access to clean water, waste disposal (sani-tation), limited family income, parents’ low educational level,andearlycessationofbreastfeedingmaycontribute to the children’s illnesses and mortality.11,12 Worldwide,

10%ofalldiseasesrecordedinchildrencouldbeprevented if governments invested more in access to clean water, hygienemeasures,andbasicsanitation.13

The factthat more than onemillion children dieeach yearasaresultofacuterespiratorydiseases,60%ofthese deathsbeingrelatedtoenvironmentalpollutants,cannotbe ignored.10 Degradedecosystems,environmentalsmoke,air

pollution, andclimate changes arethe likelyfactors that cause changesin the health statusof this population.14,15

theairways,duetochangesintherespiratorysystem bal-ance and theirinfluence onthe interactions between the host,pathogen,andenvironment,increasingthelikelihood ofinfectioninthatpopulation.16,17

Dependingontheirage,gender,geographicregion,and socioeconomicstatus,childrenhavepeculiarbehavior.They aredependentonthedevelopmentalstages characterized byphysical,psychosocial,andcognitivechanges,the poten-tialofriskexposureandparentalperceptionsregardingthe acquisitionofskillsandcapabilitiesinthepresenceof dif-ferentphysical threats inthe home environment.18,19 The

most challenging is that, while low levels of exposure to many chemicals are inevitable, little is known about the risksofsuchexposuresonthemorbidity,mortality,and sub-tlechangesinthispopulation.4,20Itisnoteworthythatthese

productsexposedintheenvironmentcanactsynergistically, whichmeansthattheircombinedeffectmaybemore harm-fultochildren.

Basedonthepremisethatthepediatricpopulationreacts inaveryuniquewaytotheenvironment,scientificadvances haveprovidedhypothesesandevenstrongargumentsabout howlifestyle and the social environmentwhere the child livescanchangetheirgenefunctioning.Drugs,pesticides, air pollutants, chemicals, heavy metals, hormones, and nutritionproducts,amongothers,areexamplesofelements thatcan resultingeneexpression alterationsthat willbe inheritedbythenextgenerations.21,22

This susceptibility is always focused on agents or spe-cific compounds in specific exposure scenarios, including intrauterineexposure,23whichcaninterfereduringcritical

andsensitivegrowthanddevelopmentalperiodsandhavea negativeimpactthroughoutlife,possiblycausingstructural and functional deficits, temporary or permanent impair-ment,andevendeath.24Theseoccurbecausechildrenhave

nocontrolovertheenvironmentintheprenataland postna-talperiods,includingthequalityoftheairtheybreathe,the watertheydrink,thefoodtheyeat,25andtheirexposureto

disease-transmittingvectors.26

Regarding infection transmitted by vectors, there is a scientific acknowledgment that Brazil with its epicenter in the Northeast region, has been showing since Octo-ber 2015 an excess number of cases of newborns with microcephalyandseverebrainabnormalities,27,28whosethe

provencausativeagentistheZikavirus,transmittedbythe Aedesaegyptimosquito,resultingfrommaternalexposure during the first months of pregnancy.29---32 Because it also

transmits dengue fever and chikungunya, the elimination ofthismosquitohasbeen considered bytheWorldHealth Organization,sinceFebruaryof2016,aninternationalpublic healthemergency.32

Stillduring pregnancy, maternalexposure tochemicals resulting from industrial, agricultural and mining activ-ities may reflect the possible increased prevalence of prematurity,33 hematopoietic cancers,34,35 birth defects,

asthma, endocrine,neurological,andbehavioral disorders oftheirchildren.36---39Asforthebiologicaleffectsof

mater-nalexposure tophysical agents,suchasionizingradiation (doseabove250mGy),theycanleadtointrauterinedeath, fetal malformations, fetal growth disorders, and carcino-geniceffects.40

Given these facts, the objectiveof this article wasto explore the scientific evidence regarding the impact of

exposure to environmental contaminants in children dur-ingsensitivedevelopmentalperiods,basedontheirspecial characteristics.

Children’sparticularcharacteristics

Due to the fact that they are going through a phase of growth and development, the pediatric population is a special demographic group concerning biology, physio-logical, metabolic, and behavioral processes, which are complexand multilayered.8,41 From the embryonic phase

tolate adolescence,childrenareoften exposedto intrin-sic risk factors (genetic, metabolic, and hereditary, very often correlated) and extrinsic or environmental factors (food,socioeconomic, geophysical, and urbanization con-ditions, as well as mother-child relationship), which may adversely affect the dynamic processes of growth and development.42,43 What determinesthe nature and

sever-ityoftheeffectsofthesefactorsonchildren’shealthisthe occurrenceof adverse environmental exposuresat differ-entstages,called‘‘criticalexposurewindows’’,‘‘windows ofvulnerability’’,44 or‘‘developmentalwindows’’,45where

thefunctionsofcellmaturation,differentiation,andgrowth areoccurringatdifferentrates.

Sinceconception, thereis a closeassociation between fetalgrowthand theenvironment,tothepointthat, ata certainperiod,growthislimitedbythespaceoftheuterine cavity.41 After9monthsofintrauterinegrowth,thechild’s

organs and systemsbecome relatively mature, enough to safely adapt tolife.46 The physical growth andfunctional

maturationof the bodywillcontinue, and mayvary from systemtosystem,fromorgantoorganandfromtissueto tissue,becauseeachchildisdifferentintheirstructureand functionatanyage.45,47

Asanexampleofthisdifferentiatedrateofchildgrowth, studies suggest that in the second month of intrauterine life,thefetalheadshouldcorrespondtohalf ofthebody, whereasatbirthitis25%,andinadulthood,itshould cor-respondto 10% of the whole physical structure.42,48 At 6

monthsoflife,thebrainmustreach50%ofitsadultweight, andat3years,itshouldhavereachedapproximately90%of thisweight.39,45Approximately50%ofthesizeofanadultis

reachedat2yearsofage.42,48Incontrast,50%oftheweight

oftheliver,heart, andkidneysofan adultis notreached untilthechildisapproximately9yearsold.Thesamepoints ingrowthofskeletalmuscleandtotalbodyweightarenot reached until near the 11th year of life.46 These periods

ofchild development areespecially sensitive toexposure tocertainbiological,chemicalagents,andphysicalfactors foundintheenvironment.46

Inchildrenyoungerthan5yearsofage,theinfluenceof environmentalfactorsismuchmoreimportantthangenetic factors. The younger the child, the more dependent and vulnerable he/she is in relation to the environment that surrounds him/her. And if that environment is not ade-quate, there is the possibility of failure regarding some aspectofchilddevelopment.42,49Inthiscontext,the

embry-onicdevelopmenttaking placeinside the mother’suterus (environment) would not be protected from the embry-otoxic effects of harmful environmental agents.50 As an

Intake

Mouse

Gastrointestinal tract

Feces Bile

Liver

Inhalation

Nose or mouse

Blood and lymph

Kidneys

Lungs

Exhaledair

Bladder

Urine

Dermal contact

Lipid tissue Extracellular

fluid

Brain

Skin, nail

Organs

Bones Tissues

Secretory glands

Secretions

Skin

Hair

Sweat Distribution and/or

Biotransformation

Excretion Absorption

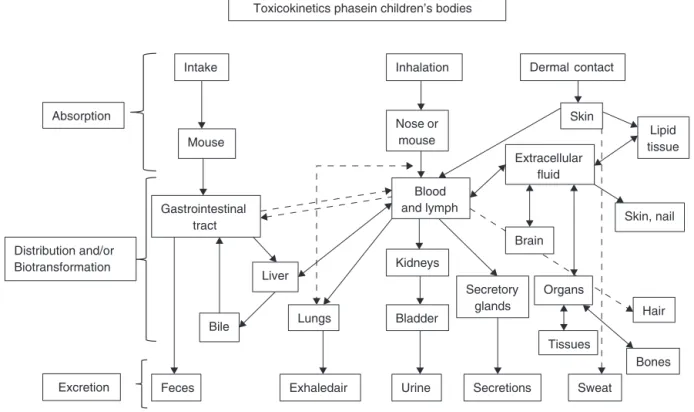

Toxicokinetics phasein children’s bodies

Figure1 AdaptedfromRuppenthal.104

pregnancy in the 1950s, led to the special attention of researchers on the occurrence of teratogenic effects of the drug on the fetus’ health, causing phocomelia with irreversibledamages.5 In2010,Japanese scientists

identi-fiedhowthalidomideinterfereswithfetaldevelopment.The drugbindstoaproteincalledcereblon(CRBN),inactivating it,resultinginlimbmalformation.51

Theprecocityandthepersistenceofadverseconditions inchildren’ssystemsororgansbeforetheircomplete mat-urationcancausetemporaryorpermanentdamagetothe normalphysicalmaturationand,consequently,totheir cur-rentandfuturehealth.52

Exposurepathwaysofenvironmentaltoxicantsin targetsystemsandorgansduringchildren’s developmentalstages

Contamination occurs through an exposure pathway, as shown in Fig. 1, between the agent in the physical envi-ronment(in utero,breast milk,oral, parenteral) andthe developmentalperiodwhen thechild wasexposed (fetal, neonatal,childhood,puberty).53Itisextremelyimportantto

knowthemagnitudeoftheadversesubstance,theduration andfrequencyofexposureandthechild’sindividual suscep-tibility,andthe introductionpathways ofthepathological agents.54,55

Breastfeeding: the ideal form of infant nutrition, it has ensured the survival of the human species, provid-ingnutritional,immunological,cognitive,psycho-affective, economic,andsocialadvantages,56,57significantlyreducing

thechild’s risk of developing severaldiseases. Influenced byfactors ofthe nursing mother,infant,and/or toxicant,

breastfeeding can introduce into the baby’s circulation several toxic substances, suchas dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), mercury and chlorinated pesticides,58

nicotine,59 lead,60andmedications,61 amongothers.While

inthematernaltoxicokineticsthebreastmilk/plasmaratio forPCBishigh,rangingfrom4to10,fororganicand inor-ganicmercuryitis0.9.60Nicotinemaybepresentinbreast

milk at the same maternal plasma concentration,and its half-life is also similar, with 60---90min of elimination in both.59 The leadexcreted inbreastmilkhasa

concentra-tionbetween10%to30%ofmaternalbloodleadvalues;as leadis notlipophilic,itis notconcentratedin themilk.60

The recommendationtodiscontinuebreast-feedingdueto the presenceof chemicals inbreastmilkis notsupported intheliterature,aslongasthefindingofthesesubstances doesnotoffertoxicitytotheinfant.53

Respiratory system --- at birth, a full-term baby has approximately 10 million alveoli, whereasat 8 yearsold, he/shewillhave300millionalveoli.62Theimpactofpassive

smokingsincetheintrauterinephasecanresultinreduced weight,length,andcephalicperimeterinthenewborn,63in

additiontotheincreaseinairwayresistance,withamean reductionof20%inforcedexpiratoryflow.64Thecontinuity

ofpostnatalparentalsmokingcanhaveadverseeffectson thechild’simmunesystemagainstpathogens,aswellason lunggrowthanddevelopment,causingafour-foldincreased riskofwheezingduringthefirstyearoflife.64---66

A child breathes more air than an adult at rest, even thoughtheadulthasagreaterlungcapacity,which corre-sponds to about 6.5l, whereas in a child this capacity is about 2l.62 Considering the body weight, the air volume

threetimestheventilationperminute(volumeofair pass-ingthroughthelungsateveryminute)thananadult,anda 6-year-oldchildhastwicethisvolume.45

As children breathe more air and tend to be more physically active than adults, inhaling toxic gases may compromisetheirpulmonaryfunction67 orexacerbate

pre-existing conditions, increasing the incidence of acute respiratory infections in this population, expressed as increased hospitalizations68 and school absenteeism.69

Thesesubstancesinclude:particulatematterinsuspension (dust, smoke and aerosols)70; pollutants of public health

concern,suchasO3,71 NO2,72CO,andSO273;lead,mercury

andvolatileorganiccompounds14;aswellasbiomassburning

residue45andtobaccosmoke.74---76

Endocrine-reproductive system: since embryonic life, events related to the child’s formation, growth and development, require hormonal interactions at specific moments.77,78 Thesehormones playacriticalrolein

coor-dinatingmultiple cellactivities, throughthe regulationof biologicalfunctionssuchasthehypothalamic-pituitaryaxis, thethyroidandsexualorgans,keepingin homeostasisthe metabolism,electrolytebalance,sleepandmood.77,79

How-ever, these activities can be negatively impacted when susceptibletoagentsofexogenousorigintothebody.Among these agents aresubstances known asendocrine disrupt-ors,alsoknownaseco-hormones,substanceswithhormonal activityorxenohormones.77,78,80

Endocrinedisruptorscanreachtheenvironmentmainly throughindustrialandurbanwaste,agriculturalrunoff,and waste release;children’s exposure tothese toxicants can occurthroughingestionoffood,dust,andwater,inhalation ofgases andparticlesinthe air,andskin contact.81 Some

arenatural substances,suchasestrogens and phytoestro-gens,whereassyntheticvarietiescanbefoundinpesticides, alkylphenols,polychlorinatedbiphenyls(PCBs),bisphenolA, foodadditives,toiletries,andcosmetics.82

During the prenatal period, endocrine disruptors can have consequences on fetal development with a greater risk of sensitizing the future reproductive capability.77,78

Thesesubstancesactbymimickingestrogenactionor antag-onizingandrogenaction;theymayresultinearlypuberty83

andhaveadverseeffectsonsexualdifferentiation,gonadal development, fecundity, and fertility, as well as sexual behavior.78,79,84 According to Alves et al.,53 the literature

suggests that sexual prematurity can also be related to accidentalexposuretocosmeticscontainingestrogenor pla-centalextracts, such asshampoo,conditioners, and body creams,amongothers,resultinginbreastsizeincreaseand transitional impotence, with regression of the condition aftertheuseoftheseproductswasdiscontinued.

Nervoussystem---fromembryogenesisonwards,the ner-vous system continues to shape its structure not only in the beginning, but throughout the entire period of child developmentuntiltheend ofadolescence,in responseto genetically programmed events and environmental influ-ences,inaseriesofcomplexprocessesthatoccuratspecific periodsintimeandspace.25,39

Atbirth,thebrainofachildreachesapproximately24% of its adult weight. The brain weight at birth is approxi-mately between 300 and 330g.At 1 year, the brainmass will be tripled, growing at a much slower pace until the 1500goftheadultphaseisreached.39,85Thepopulationof

nervecellsiscompletedaroundtheageof2years,buttotal neuronaltissuemyelinationwillnotbecompleteduntil18 yearsofage.39Becausethebrainisthemainorganofstress

andadaptation,itisatthesametimebothvulnerableand adaptable.Itinterpretsandregulatesbehavioral, neuroen-docrine,autonomic,andimmunologicalresponses.85

Vulnerable periods during the nervous system devel-opment are sensitive to environmental injuries, because they depend on the regional and temporal onset of critical developmental processes, such as proliferation, migration, differentiation, synaptogenesis, myelination, and apoptosis.39 In this sense, a wide range of

chemi-calcategories(benzene,ethanol,nicotine,methylmercury, polychlorinatedbiphenyl(PCBs),arsenic,lead,manganese, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, tetrachloroethylene, and organophosphate insecticides)36 may interfere with one

or more of these processes, leading to developmental neurotoxicity39throughingestionofcontaminatedfoodand

liquids,gasinhalation,orskincontact.81 Theresultofsuch

interferenceinthenormalontogenyofdevelopmental pro-cesses in the nervous system will be children who may present clinical disorders, such as cognitive impairment, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, mental retarda-tion,autism, and cerebral palsy, among others, that will persistthroughouttheir life.36 The developmentand

mat-uration of the nervous system, the dose and duration of exposure,aswellasthechild’snutritionalstatus,all influ-encethistoxicity.86

Inadditiontothe exposuretotoxicchemicals, biologi-calagentscan alsohavea negativeeffectonthe infant’s braindevelopment.Asmentionedbefore,thereisan asso-ciation between prenatal infection by the Zika virus and casesof microcephaly andother disorders of the nervous system in fetuses and newborns, called ‘‘congenital Zika syndrome’’.29Fetalautopsieshaveshownseveralchangesin

thebrain,suchashydrops,87,88hydrocephalusandmultifocal

dystrophiccalcificationsinthecortex,87intracranial

calcifi-cationsintheperiventricularparenchymaandpartsofthe thalamus,89celldegeneration,andnecrosis.90Thedetection

ofviralRNAandantigensintheanalyzedbraintissueswas alsoconfirmed.87,90Moreover,anophthalmologicalstudyin

infantswithmicrocephalycausedbythevirusdemonstrated theriskofvisual impairmentinthesechildren,duetothe presenceofbilateralmacular andperimacular lesionsand opticnerveabnormalities.91

Incertaincases,thechild’svulnerabilitytoneurotoxins mayberelatednotonlytothestagesofneurodevelopment, but also to the immaturity or failure of other protective barriers,asthe blood---brain barrier92,93 andthe placental

barrier.54,55,94

Blood---brain barrier--- its primary function is to main-taina safeandconstantchemicalenvironmentfor proper functioning of the brain and protect it from xenobi-otics,bacteria, fungi,parasites, viruses, andautoimmune reactions.46Thisprotectionisduetoitslowerpermeability,

havingexclusionmechanismsthatpreventthediffusionof adversepolarsubstanceswithlowmolecularweight,suchas drugs,foodadditives,pesticides,andmetals,suchasnickel, chromium,andmercury.54,93 Thisbarrierisnotfully

devel-opedatbirth;thismaybeoneofthereasonsforthehigher toxicityofchemicalsinnewborns.93Anexampleisthe

whichmayresultinencephalopathy(kernicterus)inthefirst weeksoflife,withirreversibleneurologicaldamage.While bilirubin concentrations of 40mg/dL are not tolerated in neonates,thesedonotappeartocauseanyadverseeffects onadults.46

Placental barrier --- in additionto protectingthe fetus againstthepassageofharmfulsubstancesfromthemother’s body,itperforms theexchangeofvitalnutrientsfor fetal development.46Infact,theplacentaisnotaneffective

pro-tectivebarrieragainsttheinflowofforeignsubstancesinto the circulation, at a time of extreme fetal vulnerability. Althoughtherearesomebiotransformationmechanisms(or metabolization)thatcanpreventtheplacentalpassageof thesesubstancesthroughadeactivatingmechanism, mak-ingtheresultingproductlesstoxicthanitsprecursor,54,55,94

morethan200chemicalproducts,foreigntotheorganism, weredetectedintheumbilicalcordblood.36

Recent studies have reported that the placenta is not immune to the Zika virus. A group of researchers from Fiocruz26identifiedtracesofviralDNAintheplacentaltissue

ofapregnantwomanwhohadthepregnancyinterrupted. ThestudydisclosedtheimmunopositivityinHofbauercells, present in the placenta and which, in pregnant women, shouldactasafetalprotectionfactor.Theresearchers sus-pectthat the virus maybe using the migratory ability of thesecellstoreachthefetalvessels.Martinesetal.90 also

showed in their study the detection of Zika viral RNA in placentaltissueofearlymiscarriages.

Prenatalexposuretosubstancessuchasnicotine,lead, anestheticgases,carbonmonoxide,antineoplasticagents, andsolvents,amongothers,can havenegativeeffects on fetal development54,94 and cause damage that cannot be

predicted untiltheir effects are observed in adulthood.95

Methylmercury,whencrossingtheplacenta,caneasilyreach highlevelsintheumbilicalcordbloodandproduceavariety ofcongenitalabnormalities, includingmicrocephaly, men-talretardation,andmotordeficit.96Asforlead,inaddition

tocrossing thebrainandthe placentalbarriersand being secretedinmilk,itisquicklyandeasilydistributedtoall tis-sues.Thetoxicityofthissubstancewheningestedbyinfants andyoung children may reachan absorption rateof 50%, witheffectsonthecentralandperipheralnervoussystem.97

As observed, the effects of environmentaltoxicants in thecomplexprocessofthenervoussystemdevelopmentcan leadtoanabnormalneuropsychomotordevelopment,with transientorpersistentdeficits,withpossibleandmore insid-iousconsequencesinadulthood.39,46Thedevelopment,the

maturationofthenervoussystemanddetoxification mech-anisms, the dose, exposure duration, and the nutritional statusofthechildinfluencethetoxicity.86

Metabolismanddigestion:thegastrointestinal(GI)tract, aswell asthe skin and the respiratory system, is in con-stantinteractionwiththeenvironment.Dependingonthe ageofthechild,theGIfunctionasaprotectivebarrierisas importantasitsdigestionandabsorptionfunctions.96Young

childrenhaveafastermetabolicrateanddigesttheirmeals faster than adults. They ingest more food and water per bodyweightunit.98Anewbornconsumesagreateramount

ofwater(equivalentto10---15%ofbodyweight)thananadult (2---4%ofbodyweight).99 Infants whoareformula-fedmay

have a mean dailyconsumption of 140---180mL/kg/day of water,whichwouldbeequivalenttoconsuminganaverage

of35cans(360mL)ofnon-alcoholicbeveragesforan aver-ageadultmale.99Preschoolchildren(1---5years)ingestthree

tofourtimesmorefoodperkilogramofbodyweightthan theaverageadult.98

Children,duetotheirlittlevarieddiet,containingmore fruits and vegetables,have a greater chance of exposure tocontaminated foodsandliquids.96 Orally ingested

envi-ronmentaltoxinscanbemodifiedintheGItractbygastric pH, digestive enzymes or bacteria living in the intestine. Whentheyareabsorbedbytheskinorbyinhalation(through sinusdrainageintothepharynxandesophagus),theycanbe secreted intothe intestinallumenthroughthebiliary sys-temandleadtogastrointestinaltoxicity.96 Asthedigestive

system is not capableof easily eliminating allthe toxins, childrenmaystillbeexposedtotheseagentsfor alonger periodof time.82,100 Common childhooddisorders,suchas

intestinalconstipation,canalsosignificantlyincreasetoxin absorptionbydelayingtheintestinaltransittime.96

In this context, it is noteworthy that the rate of cal-cium transport in the body of newborns and infants is approximately five times that of adults.101 If the child’s

diet is deficient in iron or calcium and exposure to lead occurs,thesmallintestine,stilldeveloping,willabsorbthis harmful agent, which will compete with calcium for cell transportationatahighpace.Thus,therateoflead absorp-tion children may also be five times higher than that by adults.96,101These leadconcentrationsin children’sblood,

especiallyinearlychildhood,mayalsobecorrelatedtothe intakeofdustcontainingthemetal,duetotheoral explo-rationoccurringinthisphaseofdevelopment,fromsources withinthehouseholdandthecontaminatedsoil.44,102

AcuteexposurestotoxicsubstancesabsorbedintheGI tractaresometimesdifficult todiagnose. Clinicalpictures of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and GI bleeding may sug-gestaninfectiousetiologycontaminationthroughingestion of non-potable water and contaminated food,due to the lackofhandhygieneduringmealpreparation.13However,if

thereareothersignsinvolvingotherorgans,suchas drowsi-ness,exposuretoenvironmentaltoxinsmustbesuspected, particularly heavy metals such asnickel, cadmium, lead, andmercury.96Incasesofethanolintoxication,thelimited

glycogen reserves in infants and preschool children may increasetheriskofhypoglycemia.103

Excretory system: differences between children and adults, regarding the susceptibility to intoxications, can resultfromthecombinationoftoxicokinetics, toxicodynam-ics,and exposurefactors.104 Kineticfactorsareespecially

important in the postnatal period, largely as a result of the immaturityof theexcretory system,either due toits reduced enzymaticmetabolism and/or renal excretion.105

Duringfetallife,thekidneyshavelittleexcretoryfunction due to the placenta, which also has this function.106 The

maturation and nephrogenicinduction usually occur after the36thweekofpregnancy.107Inthissense,preterminfants

The glomerular filtration rate of a child is a third of theratefoundinadults,whichallowsharmfulchemicalsto remainforlongerperiodsinthechild’sbody,amongthem leadandmercury.41AccordingtoCapitani,97childrenhavea

retentionrateintheleadexcretionprocessofaround30%, while inadultsitisaround1---4%. Theseheavymetals can makethe kidneysincapabletofilterthewaste,salts, and liquids in the blood, which may result in the loss hydro-electrolytehomeostasis,leadingtoacuterenalfailure.109

Dermal exposure: the skin is the organ derived from embryonicmesodermandectodermandthemostextensive organofthehumanbody.110The developmentandgrowth

offetalskinischaracterizedbyaseriesofsequential and strictlycontrolledsteps,whichdependonavarietyofcell interactionsthatconstitutetheorgan.Itspresenceisvital for thefunctionsof mechanicalprotection, thermoregula-tion,immunosurveillance,andmaintenanceofabarrierthat preventstheinsensitivelossofbodyfluid.111

Whilethe permeabilityof theskinbarrier isstillunder developmentinpreterminfants,resultinginahigher percu-taneousabsorptionofchemicals,9afull-termnewbornhas

amorematureskin,whosebarrierpropertiesaresimilarto those of older children and adults.112 Infants have a

sur-face area relative to volume three times that of adults, andin childrenthis proportionis two-foldhigherper unit of bodyweightwhencomparedtoadults.45,99 As theyare

highlyactive,theytendtohavemoreskincuts,abrasions, andrashes,thusincreasingthepotentialforskinabsorption ofxenobioticsandtoxicants,suchasdustcontaminatedwith heavymetals.45,111,112Concentratedammoniacanproduce,

in contact withthe child’s skin, tissue necrosisand deep burns.Theseburns,dependingonthesizeof theaffected area,cansecondarilycauseacuterenalfailure.109

Behavioral development:child behavioraldevelopment can include changes in maturation depending on the child’s relationship with the environment. This develop-ment can have four interrelated aspects, such as: motor skills (gross and fine); cognitive ability; emotional devel-opment; and social development. Any alteration in one of these areas can affect the development of the other three.46

Small children are powerless and helpless. With their peculiarbehaviorsandhabits,theyliveinaplayfulworld, without fearing their limits of exposure to any mechani-calenergy.Withtheirextraordinarycuriosity,theyapproach objectswithsourcesofthermalandelectrical energy,put insidetheirmouthsorbreatheinagentscontainingchemical energy,19 whichtheyfindintheirenvironment,leftwithin

their reach,effectivelycontributingto increasethe num-berofcasereportsofinjuriescausedbychemical,physical, andbiologicalagents, mostlyunintentional,whose results areoftendestructivetotheentirefamily.113

Inbrief,thefollowingpointsarenoteworthy:

1. A child is not a small adult. They differ regarding theirphysiology,metabolism,growth,development,and behavior. Fromthe intrauterinestage until theend of adolescence,thephysicalgrowthandfunctional matura-tionoftheirbodiesareatadifferentiatedandconstant rhythm.Exposuretoenvironmentalthreatsatthese sen-sitivestagesofthechild’slifemaynegativelyinfluence

these dynamic processes, and may cause irreversible damage.

2. Worldwide,childrenareexposedtoenvironmental con-taminants,acknowledgedornot,whichsilently deterio-ratetheirhealth,damaging theirfutureachievements, with physical, emotional, and social consequences, in additiontothe burdenfor thefamily, society,andthe stateasawhole.

3. To identifythecauses andunderstand themechanisms involvedinthegenesisofenvironmentalharmina pedi-atricpatientisverydifficultandachallengetoscience. Epidemiologicaldatagenerallyfocusonassessing expo-suretoindividualcontaminantsatrelativelyhighdoses. However,manysituationsintherealworld,involve low-dose, long-term exposure tosingleor multiple agents. Withthe exception ofsome chemicals, thereare rela-tivelyfewdataonthemechanismsinvolvedinthegenesis ofthesedamagesinthedevelopmentofchildhood dis-eases.

4. The occurrence of these damages and their determi-nantsinchildhoodhas,askeyfactors,povertyandlack of access toinformation oninherent health practices. Theimpactsonchildren’shealthcausedbythe combina-tionof classicrisks(homeenvironmentalpollutionand non-potablewater) andmodernrisks (toxicchemicals, hazardous waste, air pollution and climate changes), varygreatlybetweenandwithindevelopingcountries. 5. Thechild’srightstoasafeenvironmenttogrow,develop,

play, and learn are decisive arguments for the state todefine effectivestrategies topromotehealthy envi-ronments,whichwillprotectchildrenfromeventsthat are harmful to their health, that will monitor these trendsovertimeandpromoteinterventionswherethey are most needed. Articulatedintra and inter-sectorial actionsthat promotetherecordingand surveillanceof environmentalriskstochildren’shealthshouldbea con-tinuedpriorityinpublichealthcare.

6. Therelationshipbetweenresearchandpoliticsarerarely direct---frompoliticsreportingtotheresearch,orvice versa. Research and politics appear to work as par-allel groups, sometimes interconnected by interests, occasionally feedingoneach other.Relevant academic discussionsindifferentfieldsofknowledgeandanactive state on the main issues that affect the lives of chil-dren are strategic actions for the survival of future generations.Studiesoneconomicandsocialimpactsand children’s relationship withtheir physical environment indifferentfieldsofknowledgeareessentialforthe sur-vivaloffuturegenerations.

7. Thechildren’senvironmentalhealthneedstobecomean adultscienceintheacademicworldandinsociety.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

gov/pmc/articles/PMC1625885/pdf/amjphnation00639-0074. pdf[cited13.01.15].

2.WHO.Children’sHealthandtheEnvironment---aglobal per-spective.Aresourceguideforthehealthsector.Geneva:World Healthorganization;2005.Availablefrom:http://apps.who. int/iris/bitstream/10665/43162/1/9241562927eng.pdf

[cited12.07.15].

3.David B. Introduction. In: Making a difference: indicators to improve children’s environmental health. Geneva:World HealthOrganization;2003.p.1---2.

4.BrentRL,WeitzmanM.Thecurrentstateofknowledgeabout the effects, risks, and science of children’s environmental exposures.Pediatrics.2004;113:S1158---66.

5.The NationalAcademiesPress---NAP. Children’s health,the nation’swealth:assessingandimprovingchildhealth.National ResearchCouncilandInstituteofMedicine.Washington,DC: TheNationalAcademiesPress;2004.p.45---90.

6.Landrigan PG, Garg A. Children are not little adults. In: Pronczuk-Garbino J, editor. Children’s health and the environment. A global perspective. Geneva: World Health Organization;2005.p.3---16.

7.Paris EB.Laimportancia delasaludambientalyelalcance de las unidades de pediatría ambiental. Rev Med Chile. 2009;137:101---5.

8.Prüss-ÜstünA,CorvalánC.Preventingdiseasethroughhealthy environments:towardsanestimateoftheenvironmental bur-denofdisease.Geneva:WorldHealthOrganization;2006.

9.WHO. Principlesfor evaluatinghealthrisksinchildren asso-ciated with exposure to chemical. Environmental Health Criteria N◦ 237. Geneva: World Health Organization;

2006. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/ 10665/43604/1/924157237Xeng.pdf[cited16.03.15]. 10.UnitedNations Children’s Fund. Compromissocom a

sobre-vivênciainfantil:umapromessa.Relatóriodeprogresso2014. Resumoexecutivo.Brasil:UNICEF;2014.

11.ErcumenA,GruberJS,ColfordJMJr.Waterdistributionsystem deficienciesandgastrointestinalillness:asystematicreview andmeta-analysis.EnvironHealthPerspect.2014;122:651---60.

12.RodriguezL,CervantesE,OrtizR.Malnutritionand gastroin-testinalandrespiratoryinfectionsinchildren:apublichealth problem.IntJEnvironResPublicHealth.2011;8:1174---205.

13.Prüss-UstünA,BartramJ,ClasenT,ColfordJM,CummingO, CurtisV,etal.Burdenofdiseasefrominadequatewater, san-itation and hygiene in low- and middle-income settings: a retrospective analysisofdatafrom 145countries.Trop Med IntHealth.2014;19:894---905.

14.Mello-da-SilvaCA,FruchtengartenL.Riscosquímicos ambien-taisàsaúdedacrianc¸a.JPediatr(RioJ).2005;81:S205---11.

15.Quiroga D.La historia ambiental pediátrica.In: Manualde saludambientalinfantil.Chile:LOMEditores;2009.p.27---31.

16.duPrelJB,PuppeW,GrondahlB,KnufM,WeiglJAI,Schaaff F,etal.Aremeteorologicalparametersassociatedwithacute respiratorytractinfections?ClinInfectDis.2009;49:861---8.

17.Martins AL, Trevisol FS. Internac¸ões hospitalares por pneu-moniaem crianc¸as menoresde cincoanosdeidadeem um hospital noSuldoBrasil.Revistada AMRIGS(PortoAlegre). 2013;57:304---8.

18.Promoting healthand preventing illness.Hagan JF, ShawJS, DuncanPM,editors.Brightfutures:guidelinesforhealth super-vision ofinfants, children,and adolescents. 3rded.Pocket Guide.ElkGroveVillageIL:AmericanAcademyofPediatrics; 2008,xii.

19.Waksman RD, Blank D, Gikas RM. Injúrias ou lesões não-intencionais ‘‘acidentes’’ na infância e na adolescência. São Paulo: MedicinaNet;2010. Available from:http://www. medicinanet.com.br/conteudos/revisoes/1783/injuriasou lesoesnaointencionais%E2%80%9Cacidentes%E2%80%9Dna infanciaenaadolescencia.htm[cited14.06.15].

20.California ChildcareHealth Program--- CCHP.Environmental health. 1st ed. California Training Institute. University of California, San Francisco Schoolof Nursing, Department of FamilyHealthCareNursing;2006.

21.Smith MT, McHale CM, Wiemels JL, Zhang LP, Wiencke JK, ZhengSC,etal.Molecularbiomarkersforthestudyof child-hoodleukemia.ToxicolApplPharmacol.2005;206:237---45.

22.Edwards TM, Myers JP. Environmental exposures and gene regulation in disease etiology. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1264---70.

23.Juberg DR. Introduction. In: Are children more vulnerable toenvironmental chemicals?Scientificand regulatoryissues inperspective.NewYork:American Councilon Scienceand Health;2003.p.11---6.

24.HertzmanC.Thecasefor anearlychildhooddevelopmental strategy.Isuma.2000;1:11---8.

25.WigleDT.Environmentalthreatstochildhealth:overview.In: Childhealthandtheenvironment.NewYork:OxfordUniversity Press;2003.p.1---26.

26.Fiocruz. Pesquisa da Fiocruz Paraná confirma transmissão intra-uterinadozikavírus.Brasil:FiocruzParaná;2016. Avail-able from: http://portal.fiocruz.br/pt-br/content/pesquisa- da-fiocruz-parana-confirma-transmissao-intra-uterina-do-zika-virus[cited28.03.16].

27.PAHO, WHO. Epidemiological alert. Neurological syn-drome,congenital malformations, and Zika virus infection. Implications of public health in the Americas. USA: Pan AmericanHealthOrganizationandWorldHealthOrganization; 2015. Available from: http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php? option=comdocman&task=docview&Itemid=270&gid=32405& lang=en[cited03.01.16].

28.Brasil.MinistériodaSaúde.SecretariadeVigilânciaemSaúde. Protocolodevigilânciaerespostaàocorrênciade microce-falia---EmergênciadeSaúdePúblicadeImportânciaNacional ---ESPIN.Versão1.3.Brasília:MinistériodaSaúde;2016.

29.CostaF,SarnoM,RicardoKhouriR,FreitasBP,IsadoraSiqueira I,RibeiroGS,etal.Emergenceofcongenitalzikasyndrome: viewpointfromthefrontlines.AnnInternMed.2016.Available from:http://annals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2498549[cited 24.03.16].

30.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Zika virus epidemic in the Americas: potential association with microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome (first update). Stockholm: ECDC; 2016, 21 January 2016. Available from:

http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/rapid-risk-assessment-zika-virus-first-update-jan-2016.pdf [cited 24.03.16].

31.RasmussenSA,JamiesonDJ,MargaretA,HoneinMA,Petersen LR.Zikavirusandbirthdefects---reviewingtheevidencefor causality.Specialreport.NEnglJMed.2016:1---7.

32.WHO.WHODirector-Generalsummarizestheoutcomeofthe EmergencyCommitteeregardingclustersofmicrocephalyand Guillain-Barrésyndrome.Geneva:WorldHealthOrganization; 2016. Available from: http://who.int/mediacentre/news/ statements/2016/emergency-committee-zika-microcephaly/ en/[cited28.03.16].

33.WinchesterP,ProctorC,YingJ.County-levelpesticideuseand riskofshortenedgestationandpretermbirth.ActaPaediatr. 2016;105:e107---15.

34.ChenM,ChangCH,TaoL,LuC.Residentialexposureto pesti-cideduringchildhoodandchildhoodcancers:ameta-analysis. Pediatrics.2015;136:719---29.

35.Curvo HR, Pignati WA, Pignatti MG. Morbimortalidade por câncerinfanto juvenilassociadaaousoagrícolade agrotóx-icosnoEstado de MatoGrosso,Brasil. CadSaúde Coletiva. 2013;21:10---7.

37.EskenaziB,BradmanA,CastorinaR.Exposuresofchildrento organophosphatepesticidesandtheirpotentialadversehealth effects.EnvironHealthPerspect.1999;107:S409---19.

38.Turner MC,Wigle DT,Krewski D.Residential pesticides and childhoodleukemia:asystematicreviewand meta-analysis. EnvironHealthPerspect.2010;118:33---41.

39.RiceD,BaroneSJr.Critical periodsofvulnerabilityfor the developingnervoussystem:evidencefromhumansandanimal models.EnvironHealthPerspect.2000;108:511---33.

40.D’IppolitoG,MedeirosRB.Examesradiológicosnagestac¸ão. RadiolBras.2005;38:447---50.

41.SelevanSG,KimmelCA,MendolaP.Identifyingcriticalwindows ofexposure for children’s health. EnvironHealth Perspect. 2000;108:S451---5.

42.AquinoLA.Acompanhamentodocrescimentonormal.Revista dePediatriaSOPERJ.2011;12:15---20.

43.Romani SA, Lira PI. Fatores determinantes do crescimento infantil.RevBrasSaúdeMaterInfant.2004;4:15---23.

44.Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry --- ATSDR. Why are children often especially susceptible to the adverse effects of environmental toxicants? In: Principles of pediatric environmental health; 2012. Available from:

http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.asp?csem=27&po=3

[cited13.03.15].

45.WHO. Children’s Health and the Environment. Children are not little adults. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/ceh/capacity/ Children arenotlittleadults.pdf[cited12.01.15].

46.TheNationalAcademiesPress--- NAP.Specialcharacteristics ofchildren.In:Pesticidesinthedietsofinfantsandchildren. NationalResearchCouncil(US)CommitteeonPesticidesinthe DietsofInfantsandChildren.Washington,DC:TheNational AcademiesPress;1993.p.24---44.

47.Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry --- ATSDR. Whydoa child’sageand developmentalstage affect phys-iological susceptibility to toxic substances? In: Principles of pediatric environmental health; 2012. Available from:

http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.asp?csem=27&po=7

[cited12.03.15].

48.Brasil.MinistériodaSaúde.SecretariadePolíticasdeSaúde. DepartamentodeAtenc¸ãoBásica.Saúdeda Crianc¸a: acom-panhamentodocrescimentoedesenvolvimentoinfantil.Série CadernosdeAtenc¸ãoBásican◦11.(SérieA.NormaseManuais

Técnicos).Brasília:MinistériodaSaúde;2002.

49.ZickGSN.Osfatoresambientaisnodesenvolvimentoinfantil. RevistadeEducac¸ãodoInstitutodeDesenvolvimento Educa-cionaldoAltoUruguai---IDEAU.2010.Availablefrom:http:// www.ideau.com.br/getulio/restrito/upload/revistasartigos/ 176 1.pdf[cited23.01.15].

50.WilsonJC.Currentstatusofteratology.In:WilsonJC,Fraser FC,editors.Generalprinciplesandmechanismsderivedfrom animalstudies.Handbookofteratology.Generalprinciplesand etiology.NovaYork:PlenumPress;1977.p.47---74.

51.ItoT,AndoH,SuzukiT,OguraT,HottaK,ImamuraY,etal. Iden-tificationof aprimary targetof thalidomideteratogenicity. Science.2010;327:1345---50.

52.Westwood M, Kramer MS, Munz D, Lovett JM,Watters GV. Growthanddevelopmentoffull-termnonasphyxiated small-for-gestational-agenewborns:follow-upthroughadolescence. Pediatrics.1983;71:376---82.

53.AlvesC,FloresLC,CerqueiraTS,TorallesMB.Exposic¸ão ambi-entalainterferentesendócrinoscomatividadeestrogênicae suaassociac¸ãocomdistúrbiospuberaisemcrianc¸as.CadSaúde Pública.2007;23:1005---14.

54.Agencia Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária --- ANVISA. Modulo III. Fundamentos de toxicologia.Fase 1 --- Exposic¸ão; 2006. Available from: http://ltc-ead.nutes.ufrj.br/toxicologia/ mIII.fase1.htm[cited13.06.15].

55.StolfA, DreifussA, VieiraFL.Farmacocinética.In:III Curso deVerãoemFarmacologia.Paraná:UFPRBiológicas;2011.p. 3---22.

56.Chaves RG, Lamounier JA, César CC. Medicamentos e amamentac¸ão: atualizac¸ão e revisão aplicadas à clínica materno-infantil.RevPaulPediatr.2007;25:276---88.

57.Landrigan PJ, Sonawane B, Mattison D, McCally M, Garg A. Chemical contaminants inbreastmilk and theirimpacts on children’shealth: anoverview. EnvironHealth Perspect. 2002;110:A313---5.

58.SolomonGM,WeissPM.Chemicalcontaminantsinbreastmilk: timetrendsandregionalvariability.EnvironHealthPerspect. 2002;110:A339---47.

59.PrimoCC,Ruela PB,BrottoLD,GarciaTR,LimaEF.Efeitos danicotina maternanacrianc¸a emamamentac¸ão. RevPaul Pediatr.2013;31:392---7.

60.Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry --- ATSDR. Principlesofpediatric environmental health. Howare new-borns, infants, and toddlers exposed to and affected by toxicants? In: Principles of pediatric environmental health; 2012.Availablefrom:http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem. asp?csem=27&po=9[cited14.03.15].

61.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria da Atenc¸ão à Saúde.DepartamentodeAc¸õesProgramáticaseEstratégicas. Amamentac¸ãoeusodemedicamentoseoutras substâncias. MinistériodaSaúde,SecretariadaAtenc¸ãoàSaúde, Departa-mentodeAc¸õesProgramáticaseEstratégicas.2nded.Brasília: MinistériodaSaúde;2014.

62.PinkertonKE,JoadJP.Themammalianrespiratorysystemand criticalwindowsof exposuresfor children’shealth. Environ HealthPerspect.2000;108:S457---62.

63.Zhang L, González-Chica DA, Cesar JA, Mendoza-Sassi RA, Beskow B, Larentis N, et al. Tabagismo maternodurante a gestac¸ão emedidas antropométricasdo recém-nascido: um estudode base populacional noextremo suldo Brasil.Cad SaúdePública.2011;27:1768---76.

64.Stocks J, Desateaux C.The effectof parental smoking on lung function and development during infancy.Respirology. 2003;8:266---85.

65.US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the surgeon general. Atlanta: Cen-ters for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44324 [cited 15.11.15].

66.SchvartsmanC,FarhatSC,SchvartsmanS,SaldivaPH.Parental smokingpatternsandtheirassociationwithwheezingin chil-dren.Clinics.2013;68:934---9.

67.Castro HA, Cunha MF, Mendonc¸a GA, Junger WL, Cunha-Cruz J,LeonAP. Effectof air pollutiononlungfunction in schoolchildren inRiodeJaneiro,Brazil.RevSaudePublica. 2009;43:26---34.

68.RosaAM,IgnottiE,HaconSdeS,CastroHA.Analysisof hospi-talizationsforrespiratorydiseasesinTangarádaSerra,Brazil. JBrasPneumol.2008;34:575---82.

69.AbdulbariB,MadeehaK,NigelJS.Impactofasthmaandair pollution on schoolattendance of primary school children: aretheyatincreasedriskofschoolabsenteeism?JAsthma. 2007;44:249---52.

70.RigueraD,AndréPA,ZanettaDM.Poluic¸ãodaqueimadecana esintomasrespiratóriosemescolaresdeMonteAprazível,SP. RevSaúdePública.2011;45:878---86.

71.Jasinski R, Pereira LA, Braga AL. Poluic¸ão atmosférica e internac¸õeshospitalarespordoenc¸asrespiratóriasemcrianc¸as eadolescentesemCubatão, SãoPaulo,Brasil,entre1997e 2004.CadSaúdePública.2001;27:2242---52.

asthma and pneumonia in children: the influence of loca-tiononthemeasurementofpollutants.ArchBroncopneumol. 2012;48:389---95.

73.OstroB, RothL, MaligB, MartM.Theeffects offine parti-clecomponentsonrespiratoryhospitaladmissionsinchildren. EnvironHealthPerspect.2009;117:475---80.

74.Pereira ED, Torres L, Macêdo J, Medeiros MM. Efeitos do fumo ambiental no trato respiratório inferior de crianc¸as comaté5anosdeidade-Ceará.RevSaúdePública.2000;34: 39---43.

75.CarvalhoLM,PereiraED.Morbidaderespiratóriaemcrianc¸as fumantespassivas.JPneumol.2002;28:8---14.

76.CoelhoSA,RochaAS,JongLC.Consequências dotabagismo passivoemcrianc¸as.CiencCuidSaúde.2012;11:294---301.

77.Landrigan P, Garg A, Droller DB. Assessing the effects of endocrinedisruptorsintheNationalChildren’sStudy.Environ HealthPerspect.2003;111:1678---82.

78.Pryor JL,Hughes C,Foster W, Hales BF, RobaireB. Critical windows of exposure for children’s health: the reproduc-tivesysteminanimalsandhumans.EnvironHealthPerspect. 2000;108:S491---503.

79.Guimarães RM, Asmus CI, Coeli CM, Meyer A. Endocrine-reproductivesystem’scriticalwindows:usageofphysiological cyclestomeasurehumanorganochlorineexposurebiohazard. CadSaúdeColet.2009;17:375---90.

80.Koifman S, Paumgartten FJ. O impacto dos desreguladores endócrinos ambientais sobre a saúde pública. Cad Saúde Pública.2002;18:354---5.

81.WHO. Effects of human exposure to hormone-disrupting chemicals examinedinlandmarkUN report. Geneva:World HealthOrganization;2013.Availablefrom:http://www.who. int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/hormonedisrupting 20130219/e/[cited26.01.15].

82.GuimarãesRM,AsmusCI.Porquêumasaúdeambiental infan-til?Avaliac¸ãodavulnerabilidadedecrianc¸asacontaminantes ambientais.Pediatria(SãoPaulo).2010;32:239---45.

83.AksglaedeL,JuulA,AnderssonAM.Thesensitivityofthechild tosexsteroids:possibleimpactofexogenousestrogens.Hum Reprod.2006;12:341---9.

84.FloresAV,RibeiroJN,NevesAA,QueirozEL.Organochlorine: apublichealthproblem.AmbientSoc.2004;7:111---24.

85.NeedlmanRD.Crescimentoedesenvolvimento.In:Behrman RE,KliegmanRM,JensonHB,editors.Nelson,Tratadode pedi-atria.17thed.RiodeJaneiro:Elsevier;2005.p.25---71.

86.Soldin OP, Hanak B, Soldin SJ. Bloodlead concentrationin children:newrange.ClinChimActa.2003;327:109---13.

87.MlakarJ,KorvaM,TulN,Popovi´cM,Poljˇsak-PrijateljM,Mraz J. Zika virus associated with microcephaly. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:951---8.

88.Sarno M, Sacramento GA, Khouri R, Rosário MS, Costa F, ArchanjoG,etal.Zikavirusinfectionandstillbirths:acaseof hydropsfetalis,hydranencephalyandfetaldemise.PLoSNegl TropDis.2016;10:e0004517.

89.Kline MW, Schutze GE. What pediatricians and other clini-ciansshouldknowaboutzikavirus.JAMAPediatr.2016;170: 309---10.

90.Martines RB, Bhatnagar J, Keating MK, Silva-Flannery L, MuehlenbachsA,GaryJ,etal.Notesfromthefield:evidence ofZikavirusinfectioninbrainandplacentaltissuesfromtwo congenitally infectednewbornsand twofetallosses: Brazil, 2015.MMWRMorbMortalWklyRep.2016;65:159---60.

91.de Paula Freitas B, de OliveiraDias JR, Prazeres J, Sacra-mento GA, KoAI, Maia M, et al. Ocular findings ininfants withmicrocephalyassociatedwithpresumed zikavirus con-genitalinfectioninSalvador,Brazil.JAMAOphthalmol.2016. E1-6. Available from: http://archopht.jamanetwork.com/ article.aspx?articleid=2491896[cited03.03.16].

92.Banks WA. Characteristics of compounds that cross the blood---brainbarrier.BMCNeurol.2009;9:S3.

93.Rojas H, Ritter C,Pizzol FD. Mechanisms ofdysfunction of theblood---brainbarrierincriticallyillpatients:emphasison theroleofmatrixmetalloproteinases.RevBrasTerIntensiva. 2011;23:222---7.

94.Silva AL. Interferentes endócrinos no meio ambiente: um estudodecasoemamostrasdeáguainnaturaeefluenteda estac¸ãodetratamentodeesgotosdaRegiãoMetropolitanade SãoPaulo[dissertation].USP:ProgramadePós-Graduac¸ãode SaúdePública;2009.

95.Weiss B. Vulnerability of children and the developing brain to neurotoxic hazards. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:375---81.

96.Sreedharan R, Mehta DI. Gastrointestinal tract. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1044---50.

97.CapitaniEM.Metabolismoetoxicidadedochumbonacrianc¸a enoadulto.Medicina(RibeirãoPreto).2009;42:278---86.

98.Chaudhuri N, Fruchtengarten L. Where the child lives and plays:aresourcemanualforthehealthsector.In: Pronczuk-GarbinoJ,editor.Children’s healthand theenvironment: a globalperspective.Geneva:WorldHealthOrganization;2005. p. 29---39 [chapter 3]. Available from: http://whqlibdoc. who.int/publications/2005/9241562927eng.pdf [cited 10.03.15].

99.Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry --- ATSDR. Principlesofpediatricenvironmentalhealth.Whatarespecial considerationsregardingtoxicexposurestoyoungand school-agechildren,aswellas adolescents?;2012. Availablefrom:

http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.asp?csem=27&po=10

[cited15.03.15].

100.MillerMD,MartyMA,ArcusA,BrownJ,MorryD,SandyM. Dif-ferencesbetweenchildrenandadults:implicationsforrisks assessmentatCaliforniaEPA.IntJToxicol.2002;21:403---18.

101.TheNationalAcademiesPress---NAP.Adversehealtheffects ofexposuretolead.In:Measuringleadexposureininfants, children,andothersensitivepopulations.Washington,DC:The NationalAcademyPress;1993.p.31---93.

102.PaustenbachK,FinleyB,LongT.Thecriticalroleofhousedust inunderstandingthehazardsposedbycontaminatedsoils.Int JToxicol.1997;16:339---62.

103.BucaretchiF,BaracatEC.Acutetoxicexposureinchildren:an overview.JPediatr(RioJ).2005;81:S212---22.

104.Ruppenthal JE. Toxicologia. Colégio Técnico Industrial de SantaMaria.UFSM.Redee-TecBrasil;2013.

105.Ramos CL, Targa MB, Stein AT. Perfil das intoxicac¸ões na infância atendidas pelo Centro de Informac¸ão Toxicológica do Rio Grande do Sul (CIT/RS),Brasil. Cad SaúdePública. 2005;21:1134---41.

106.AltemaniJM.Dimensões renaisem recém-nascidos medidas peloultrassom:correlac¸ãocomidadegestacionalepeso [dis-sertation].UNICAMP:ProgramadePós-Graduac¸ãoemCiências Médicas;2001.

107.Hoy WE, Ingelfinger JR, Hallan S, Hughson MD, Mott SA, BertramJF.Theearlydevelopmentofthekidneyand implica-tionsforfuturehealth.JDevOrigHealthDis.2010;1:216---33.

108.IngelfingerJR,Kalantar-ZadehK,SchaeferF,onbehalfofthe WorldKidneyDay SteeringCommittee.Intime:avertingthe legacyofkidneydisease---focusonchildhood.RevPaulPediatr. 2016;34:5---10.

109.VogtBA,AvnerED.Insuficiênciarenal.In:BehrmanRE, Klieg-manRM,JensonHB,editors.Nelson,Tratadodepediatria,vol. 2,17thed.RiodeJaneiro:Elsevier;2005.p.1875---8.

110.NoronhaL,MedeirosF,SepulcriRP,FillusNetoJ,LuizFernando Bleggi-Torres LF.Manualde dermatologia. Curitiba: PUCPR; 2000.

112.SelevanSG,KimmelCA,MendolaP.Windowsofsusceptibility toenvironmentalexposuresinchildren.In:Pronczuk-Garbino J,editor.Children’shealthandtheenvironment.Aglobal per-spective.Geneva:WorldHealthOrganization;2005.p.17---25.