w ww . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / b j p

Original

Article

Aqueous

extract

of

Baccharis

trimera

improves

redox

status

and

decreases

the

severity

of

alcoholic

hepatotoxicity

Ana

Carolina

S.

Rabelo

a,

Glaucy

R.

de

Araújo

a,

Karine

de

P.

Lúcio

a,

Carolina

M.

Araújo

a,

Pedro

H.

de

A.

Miranda

a,

Breno

de

M.

Silva

b,

Ana

Claudia

A.

Carneiro

b,

Érica

M.

de

C.

Ribeiro

b,

Wanderson

G.

de

Lima

c,

Gustavo

H.

B.

de

Souza

d,

Geraldo

C.

Brandão

d,

Daniela

C.

Costa

a,∗aLaboratóriodeBioquímicaMetabólica,DepartamentodeCiênciasBiológicas,ProgramadePós-graduac¸ãoemCiênciasBiológicas,UniversidadeFederaldeOuroPreto,OuroPreto,

MG,Brazil

bLaboratóriodeBiologiaeBiotecnologiadeMicro-organismos,DepartamentodeCiênciasBiológicas,ProgramadePós-graduac¸ãoemCiênciasBiológicas,UniversidadeFederalde

OuroPreto,OuroPreto,MG,Brazil

cLaboratóriodeMorfopatologia,DepartamentodeCiênciasBiológicas,ProgramadePós-graduac¸ãoemCiênciasBiológicas,UniversidadeFederaldeOuroPreto,OuroPreto,MG,Brazil dLaboratóriodeFarmacognosia,EscoladeFarmácia,ProgramadePós-graduac¸ãoemCiênciasFarmacêuticas,UniversidadeFederaldeOuroPreto,OuroPreto,MG,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received23June2017 Accepted13September2017 Availableonline4November2017

Keywords:

Ethanol Redoximbalance

Baccharistrimera

Aqueousextract Hepatotoxicity

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Themetabolismofethanoloccursmainlyintheliver,promotingincreaseofreactiveoxygenspeciesand nitrogen,leadingtoredoximbalance.Therefore,antioxidantscanbeseenasanalternativetoreestablish theoxidizing/reducingequilibrium.Theaimofthisstudywastoevaluatetheantioxidantand hepatopro-tectiveeffectofaqueousextractofBaccharistrimera(Less.)DC.,Asteraceae,inamodelofhepatotoxicity inducedbyethanol.TheextractwascharacterizedandinvitrotestswereconductedinHepG2cells.Itwas evaluatedthecellsviabilityexposedtoaqueousextractfor24h,abilitytoscavengingtheradicalDPPH, besidestheproductionofreactiveoxygenspeciesandnitricoxide,andtheinfluenceonthe transcrip-tionalactivityoftranscriptionfactorNrf2(12and24h)afterexposureto200mMethanol.Theresults showedthataqueousextractwasnon-cytotoxicinanyconcentrationtested;moreover,itwasobserved adecreaseinROSandNOproduction,alsopromotingthetranscriptionalactivityofNrf2.Invivo,we pre-treatmentmaleratsFisherwith600mg/kgofaqueousextractand1hlater5ml/kgofabsoluteethanol wasadministrated.Aftertwodaysoftreatment,theanimalswereeuthanizedandlipidprofile,hepatic andrenalfunctions,antioxidantstatusandoxidativedamagewereevaluated.Thetreatmentwithextract improvedliverfunctionandlipidprofile,reflectingthereductionoflipidmicrovesiculesintheliver.It alsopromotedanincreaseofglutathioneperoxidaseactivity,decreaseofoxidativedamageand MMP-2activity.Theseresults,analyzedtogether,suggestthehepatoprotectiveeffectofB.trimeraaqueous extract.

©2017SociedadeBrasileiradeFarmacognosia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Ethanolisthemostusedalcoholinalcoholicbeveragesandits

abusiveconsumptionisassociatedwithvarioushealthproblems

worldwide(LíveroandAcco,2016).Themetabolizationofethanol occursmainlyintheliver,whereitisconvertedtoacetaldehyde byalcoholdehydrogenaseandsubsequentlyoxidizedtoacetateby

acetaldehydedehydrogenase(Cederbaum,2012).Theseenzymes

useNAD+ as cofactor and generate NADH, thus decreasingthe

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:daniela.costa@iceb.ufop.br(D.C.Costa).

NAD+/NADH ratio,affecting severalmetabolic pathways(Smith

et al., 2007), besides promoting the increase of acetaldehyde

adductsandreactiveoxygenspecies(ROS),leadingtooxidative

stress(Luetal.,2012;Hanetal.,2016).Insomecircumstances, themicrosomaloxidationsystemofethanol(CYP2E1)canbe

acti-vated,whichcontributesevenmoretotheROSformation(Smith

etal.,2007;Cenietal.,2014;Hernándezetal.,2015).

Alcoholicfattyliverdisease(AFLD)isthefirstresponseofthe livertoethanoluseandischaracterizedbyaccumulationoflipidsin hepatocytes(Cenietal.,2014).Anoptimalpharmacological

treat-mentforAFLDwouldreduceinflammatoryparameters,oxidative

stressandlipidaccumulation,andavoidfibroticevents.However,

thedevelopmentofadrugthatiscapableofactingonsomany

differentpathwaysisextremelydifficult.Forthisreason,asingle

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjp.2017.09.003

drugtherapyhasnotbeendeveloped,butcombinedtherapiesin anattempttoreversehepatocyteinjury(LíveroandAcco,2016).

Duetothegreatimportanceofoxidativestressinthe pathogen-esisofAFLD,severalstudieshavefocusedontheuseofantioxidants

to preventoxidative damage and improve liver function (Ceni

etal.,2014;Hernándezetal.,2015;LíveroandAcco,2016).ROS

canbeneutralizedbyenzymatic antioxidants,suchas

superox-idedismutase(SOD),catalase,glutathioneperoxidase(GPx)and

glutathionereductase(GR)andnonenzymaticasglutathione, vita-minsanddietaryantioxidants(Chenetal.,2015;Hanetal.,2016).

The antioxidant enzymes are mainly regulatedby thefactor-2

nuclear-erythroidfactor(Nrf-2)(Lushchak,2014;Chenetal.,2015; González et al., 2015). This factor is usually found in the cell cytoplasmassociatedwiththeECH-associatedcalcite-likeprotein (Keap-1),whichallowsitslabelinganddegradationNrf2via pro-teasome(Chenetal.,2015).However,inthepresenceofoxidative stressthefactormigrates tothenucleus,where it bindstothe

antioxidantresponse element(ARE), promotingtheantioxidant

enzymesexpression(Lushchak,2014;Chenetal.,2015;González

etal.,2015;KimandKeum,2016).

In addition to the enzymatic antioxidants, the inclusion of

antioxidantsinthedietisofgreatimportanceandthe consump-tionisrelatedtothereductionoftheriskofthedevelopmentof diseasesassociatedwiththeaccumulationoffreeradicals,since

inthesecompoundssubstancesthatactinsynergisminthe

pro-tectionof cells andtissues canbefound(Bianchi and Antunes,

1999). In fact, some studies have demonstrated the beneficial effectofnatural dietaryantioxidants(Al-Sayedetal.,2014; Al-Sayedetal.,2015;Páduaetal.,2010;Líveroetal.,2016a,b;Fahmy etal.,2017).Thereby,medicinalplantshaveattractedthe atten-tionofresearchersaspotentialagentsagainstalcoholicliverinjury becauseoftheirantioxidantpotentialandthefewsideeffects(Ding et al.,2012).However, mostplant species areonly empirically used,andtherearefewstudiesthatprovetheirtherapeuticefficacy (Foglioetal.,2006).

Inthissense,Baccharistrimera(Less.)DC.,Asteraceae,isa medic-inalplantusedinpopularcultureandwidelydistributedinSouth America(Bonaetal.,2005).InBrazil,thisplantispopularlyknown ascarquejaandusedasgastricprotector(Líveroetal.,2016a,b),

hypoglycemic (Oliveira et al., 2011), anti-inflammatory (Karam

etal.,2013)andantioxidant(Páduaetal.,2013;deAraújoetal., 2016).Somestudies arefocusedin theuseof medicinalplants

inethanol-inducedintoxication,however moststudiesuseonly

alcoholic/hydroethanolicextractsanditisknownthatthesolvent usedfortheextractionofthesecondarymetabolitesisinvolvedin thebiologicalactivityoftheseplants(Rates,2001).Basedonthese evidencesandonthefactthattherearenostudieswithaqueous extractofB.trimerainethanol-inducedhepatotoxicityavailable, ourgoalwastocharacterizethisextractandverifyitseffecton pro-tectionagainstalcoholichepatotoxicityinvitroandinvivomodel.

Materialsandmethods

Plantmaterial

TheaerialpartsofBaccharistrimera(Less.)DC.,Asteraceae,were collectedinOuroPretocity,inMinasGeraisstate,Brazil.The

spec-imenswereauthenticatedand depositedat theHerbarium José

Badini(UFOP),OUPR22.127.Afteridentification,theaerialparts weredriedinaventilatedoven(30◦C),pulverizedandstoredin plasticbottles.Toobtaintheaqueousextract,approximately100g oftheplantwasextractedwith1lofwaterfor24h,bymaceration. Thesolidswereremovedbyvacuumfiltrationandthesolventwas removedbyarotaryevaporatorat40◦C(Páduaetal.,2010).

RP-UPLC-DAD-ESI-MSanalyses

Theaqueous extract wasanalyzed in theUltraPerformance

LiquidChromatography coupledtodiode arrangementdetector

andmass spectrometry.Inthis assay,20mg ofthesample was

appliedanddilutedwith4mlofMeOH/H2O(9:1).Theeluatewas driedandresuspendedinasolutionofmethanolandthenfiltered on Chromafil®

PDVF syringe filters (polyvinylidene dilfluoride, 0.20mm)inavolumesufficienttoobtain2mg/mlconcentrationof thesample.FortheanalysisinHPLC-DAD-EM,20lofthesample

wereinjectedintotheliquidchromatograph,inthesame

condi-tionsdescribedbydeAraújoetal.(2016).

Invitrotests

DPPHradical-scavengingactivity

The percentage of antioxidant activity of each substance

was assessed by DPPH free radical assay, according to Araújo

etal. (2015).In brief,aqueousextractwasdiluted inmethanol

80%and dilutionswereperformedtoobtaintheconcentrations

(25–500g/ml).Thestandardcurvewasperformedwiththe

ref-erenceantioxidantTrolox

(6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchrome-2-carboxylic acid). As blankmethanol (80%) wasused and the

antioxidant activity was determined by the decrease in the

DPPH absorbance and the percent inhibition was calculated

usingthefollowingequation:%antioxidantactivity=(1−ASample

515/AControl515)×100.

Cellculture

Hepatocellularcarcinomacellline(HepG2)wasacquiredfrom

theCellBankfromtheFederalUniversityofRiodeJaneiro.Thecells

wereplacedinsterile75cm2growthvialscontainingtheDMEM

culture medium and supplemented with antibiotic

(Penicillin-Streptomycin)and10%(v/v)fetalbovineserum.Thebottleswere

incubatedin anovenat37◦C humidifiedwith5%carbon

diox-ide(CO2).Cellswereusedforassayswhentheconfluencereached

about80%,sothemediumwasaspiratedandthemonolayerwashed

withbufferedsaline(PBS).Afterthis,2mloftrypsinandEDTA solu-tion(0.20%and0.02%,respectively)wereused.Subsequently,the cellswerecentrifugedandthesupernatantwasdiscardedandthe

cellpelletwasresuspendedin1mlofDMEMmedium.Thecells

werethencountedwithTrypanBlue0.3%intheNeubauerchamber. Foreachexperimenttriplicatewasused,withbiologicalduplicate (totalingn=6pergroup).

Cellviabilityassay

CellviabilitywasdeterminedusingcolorimetricMTT

(3-[4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) assay

as described previously (Fotakis and Timbrell, 2005). In brief,

HepG2 cells (1×105) were cultured in 96 well-plates with or

without different aqueous extract concentrations of B. trimera

(5–600g/ml),whichwasdilutedinDMEMmedium,andethanol

(5–800mM) for 24h. After incubation, medium was removed

and MTT solution(5mg/ml) was added and incubated for

fur-ther 1h at 37◦C. Subsequently, dimethyl sulfoxide was added

todissolveformazancrystalsandtheabsorbancewasmeasured

at 570nm. The cell viability percentage was calculated based

in the formula below, where the control was assigned 100%

viability.

% ofcellviability= absorbanceabsorbanceoftreatedcontrolcells×100

ROSandNOproduction

For the determination of reactiveoxygen species and nitric

twodifferentaqueousextractofB.trimeraconcentrations(10and

50g/ml),dilutedinDMEMmedium.Afteranincubationof3h,

themediumwasremovedand200mMofethanolwasaddedwith

50Mofcarboxi-H2DCFDA(forROSproduction)or10Mof

DAF-FM(for NOproduction). Theplate wasincubated for24hand,

then,HANKSwasadded.Thereadingwasobtainedinmicroplate

reader, using 485nm for excitation and 535nm for emission

microwave.

Luciferasereporterassay

To evaluate the effect of aqueous extract of B. trimera on

transcriptionalactivityofNrf2,LuciferaseassaySystemwasused, accordingtoSilvaetal.(2011),withsomemodifications.Forthis,a kitDualLuciferaseassaySystemwasused.Briefly,1.5×105HepG2

cellswereplatedin24-wellplatesandincubatedfor24h.Then,

mediumwithoutSFB wasaddedandincubatedforfurther24h.

Afterthistime,transfectionwasperformedwith100lperwellof mix(500ngoflipofectamine,100ngofpRL-TK,400ngofpPGL37

andmediumHGtocompletethevolume).Six-hourincubationwas

carriedoutand,then,10and50g/ml ofaqueousextractwere

added.After3-hourincubation,200mMofethanolwasaddedand

anewincubationwasperformedfor12or24h.Afterthis,100l

oflysis buffer(providedbythekit)wasadded andcentrifuged

for4minat10,000rpm.Then, 15lofsupernatantand35lof LuciferaseIIreagent(LAR-II)werereadinluminometer(580nm), providingthe“NetA”value.After,50lofStopandGlo®

were added,providingthe“NetB”value.ForcalculationstheNetA/NetB ratiowasused.

Invivotests

Animals

MaleFisherrats(220–250g),obtainedfromtheLaboratoryof ExperimentalNutritionfromtheFederalUniversityofOuroPreto, werekeptoncollectivecages,ina12hlight/darkcycleatroom temperatureandwerefasted12hwithwateradlibitumbeforethe

experiment.Allanimalswereused accordingtotheCommittee

guidelinesonCareandUseofAnimalfromFederalUniversityof

OuroPreto,Brazil(No.2016/01).

Theexperimentalprotocol

Theanimalsweredividedintothreegroups:

-Controlgroup(C)(n=7):received1mlofwater;

-Ethanolgroup(E) (n=5): received1mlofwater and 1hlater 5ml/kgofabsoluteethanol(El-Naga,2015).

-AqueousextractofB.trimera(Aq)(n=7):received600mg/kgof extractand 1hlater 5ml/kgofabsoluteethanol (Páduaetal., 2010,2013,2014).

Alltreatmentswereadministratedbygavage,totalingavolume of1mlofsolution.Theanimalsweretreatedfortwoconsecutive daysand24hafterthelastethanoldose,theywereeuthanizedby deepanesthesiainducedbyisoflurane.Theyweremaintainedona 12hfasting.

Analysisofbiochemicalserumparameters

Theserumwasusedfordeterminingtheurea,creatinine,ALT, AST,proteintotal,glucose,totalcholesterol,HDL,fractionnon-HDL,

triacylglycerides.Allmeasurementswereperformedby

commer-ciallaboratorieskitsLabtest®

(LagoaSanta,MG,Brazil)andBioclin® (BeloHorizonte,MG,Brazil).

Determinationofantioxidantsystem

TheantioxidantsystemwasevaluatedbySOD,catalase,

glu-tathione peroxidaseand reductaseactivity, beyondglutathione

total (oxidized and reduced). The assay for determination of

indirectSOD-activity is based onSOD competition with

super-oxide radical, formed by self-oxidation of pyrogallol, which is

responsibleforMTTreductionandformationofformazancrystals

(MarklundandMarklund,1974).Catalaseactivitywasdetermined

based on its ability to convert hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)into

water and molecular oxygen (Aebi, 1984). Glutathione system

wasdetermined by kit (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis,MO, USA).To

determine catalase and superoxide dismutase activity, 100mg

of liver tissue washomogenized in phosphate buffer(pH 7.4).

Total glutathione and reduced/oxidize glutathione

concentra-tions were determined by the homogenization of 100mg of

tissue in 5% sulfosalicylicbuffer. For correctionof thedosages,

theprotein wasmeasured bythe Lowrymethod(Lowry etal.,

1951). After homogenization, the samples were centrifuged at

10,000×g for 10min, at 4◦C. The supernatant was collected

and used as the sample and all dosages were according to

Bandeiraetal.(2017).

Determinationofoxidativestressmarkers

Inordertoevaluateoxidativedamagethiobarbituricacid reac-tivesubstances(TBARS)andcarbonylproteinsuchasmarkerswere

used.TheTBARSconcentrationwasdeterminedbasedon

thiobar-bituricacid(TBA)bindingtooxidizedlipids,accordingtoBuegeand Aust(1978).Inthemethodfordeterminingcarbonylatedprotein, itwasused2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine(DNPH),whichreactswith carbonylgroupstogeneratethecorrespondinghydrazonethatcan beanalyzedspectrophotometrically,asdescribedbyLevineetal. (1994).Forcorrectionofthedosages,theproteinwasmeasuredby theLowrymethod(Lowryetal.,1951).

Gelatinzymography

MMP-2activitywasdetectedusinggelatinzymography.Briefly,

50mgoftissuewerehomogenizedin200ofRIPAbuffer(150mM

NaCl,50mMTris,1%IGEPAL,0.5%sodiumdeoxycholate,0.1%SDS, 1l/mlproteaseinhibitor atpH8.0).Afterhomogenization,the sampleswerecentrifugedat10,000×gfor10min,at4◦Candthe supernatantwascollectedandusedasthesample.Theactivitywas measuredaccordingtoAraújoetal.(2015).

Histologicalevaluation

For microscopic analysis, a portion of the liver from each

animal of experimental groups was fixed in 10% formalin and

immersedinparaffin.Sectionsof4mwereobtainedandtheslides

werestained withhematoxylin andeosin (H&E). The

photomi-crographswereobtainedat40×magnification(LeicaApplication

Suite,Germany).Liverhistologywasexaminedusingelevenimages obtainedatrandomfromthetissueandclassifiedforthedegreeof

microvesicularsteatosis.Theimageswereexaminedsemi

quan-titatively, considering that the degree of lipid infiltration was gradedreflectingthepercentage ofhepatocytescontaininglipid droplets.It wasgiventhevalues0–3accordingtothesteatosis,

where 0:none;1:1–33%; 2:33–66%; 3:>66%,as describedby

Bruntetal.(1999).

Statisticalanalysis

The data were analyzed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for

normality, and all data showed a normal distribution. All

values are expressed as the mean±standard error of the

mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using

one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Bonferroni posttest.

Prism 5.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to

per-formtheanalysis.Differenceswereconsideredsignificantwhen

20.0

15.0

10.0

5.0

0.0 1,2,3

4,5 7

6

11 10 9 8

121314

Time

AU

1.60 1.80 2.00 2.20 2.40 2.60 2.80 3.00 3.20 3.40 3.60 3.80 4.00

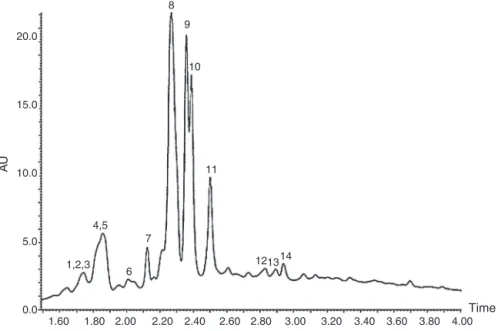

Fig.1.RP-UPLC-DADfingerprintsectionofaqueousextractofBaccharistrimera.1:3-O-feruloylquinicacid;2:4-O-caffeinoylquinicacid;3:5-O-caffeinoylquinicacid;4:3-O -caffeoyylquinicacid;5:4-O-feruloylquinicacid;6:5-O-feruloylquinicacid;7:apigenin-6,8-di-C-glucopyranosidium;8:3-O-isoferuloylquinicacid;9:5-O-isoferuloylquinic acid;10:6(8)-C-furanosyl-8(6)-C-hexosylflavone;11:6(8)-C-hexosyl-8(6)-C-furanosylflavone;12:3,4-di-O-caffeinylquinicacid;13:3,5-di-O-caffeoyylquinicacid;14: 4,5-di-O-caffeinoylquinicacid;15:4-O-isoferuloylquinicacid.

Table1

SubstancesidentifiedintheaqueousextractofBaccharistrimerabyLC-DAD-ESI-MS.

Peak Compound RT(min) UV(nm) LC–MS[M−H]−(m/z)

(fragmentationm/m)

1 3-O-feruloylquinicacid 1.73 321.1 367.29

(193.0;155.2;148.9;134.0)

2 4-O-caffeinoylquinicacid 1.74 320.1 353.38

(191.0;178.9;135.1)

3 5-O-caffeinoylquinicacid 1.75 323.1 353.38

(191.2;179.1;135.1)

4 3-O-caffeoyylquinicacid 1.86 323.1 353.38

(190.8;179.0;137.0)

5 4-O-feruloylquinicacid 1.88 323.1 367.36

(193.2;172.8;149.1;134.0)

6 5-O-feruloylquinicacid 1.96 320.1 367.38

(192.7;172.7;149.2;134.2)

7 Apigenin-6,8-di-C-glucopyranosidium 2.12 269.1;321.0 593.42

(547.1;503.0;472.9;431.1)

8 3-O-isoferuloylquinicacid 2.25 318.1 367.59

(193.1;172.8;149.1;133.8)

9 5-O-isoferuloylquinicacid 2.47 323.1 367.17

(191.2;172.8;149.1;134.1)

10 6(8)-C-furanosyl-8(6)-C-hexosylflavone 2.36 271.1;331.1 563.48

(515.1;473.1;443.0;383.1)

11 6(8)-C-hexosyl-8(6)-C-furanosylflavone 2.50 271.3;333.2 563.20

(515.1;472.9;442.9;383.2)

12 3,4-di-O-caffeinylquinicacid 2.81 282.1;320.5 515.20

(190.0;162.9;134.7)

13 3,5-di-O-caffeoyylquinicacid 2.93 283.1;321.2 515.17

(191.0;163.0;135.0)

14 4,5-di-O-caffeinoylquinicacid 2.95 286.1;320.3 515.40

(190.7;163.0;143.2;127.0)

15 4-O-isoferuloylquinicacid 3.46 322.1 367.22

(190.6;163.0;148.0)

Results

RP-UPLC-DAD-ESI-MSanalysisofaqueousextract

Twelvephenolicacidsandthreeflavonoidswereidentifiedin

theaqueousextractofB.trimera,byRP-UPLC-DAD-ESI-MS.The

RP-UPLC-DADfingerprintisshowninFig.1(Table1).

AntioxidantactivityinvitroofBaccharistrimera

Table2

Evaluationof Baccharistrimeraability to scavengingDPPHradical. The high-est concentrationofaqueous extract ofBaccharistrimera wasable to inhibit DPPHbyapproximately68%,whilethereferenceantioxidant(Trolox)required a concentrationof 300 timesgreater to inhibit thesame percentage. DPPH: 2,2-diphenyl-1picrylhydrazyl; Trolox: 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetra-trhylchroman-2-carboxylicacid.Thevaluesareexpressedasthemean±SD.

DPPHradicalscavengingactivity Inhibition%

AqueousextractofBaccharistrimera(g/ml)

500 68.1±11.1

250 30.5±1.38

100 8.10±0.90

50 3.30±0.88

25 0.59±0.27

Trolox(g/ml)

200232 95.9±0.19

175203 83.3±3.05

150174 72.0±2.82

125145 60.4±4.79

100116 47.3±1.24

75087 32.9±1.53

50058 22.0±0.77

25029 10.5±1.06

concentrationofapproximately300timeslessthantroloxisable

toinhibitthesamepercentageofDPPH(Table2).

Baccharistrimeraaqueousextractdoesnotshowcytotoxicityin HepG2cells

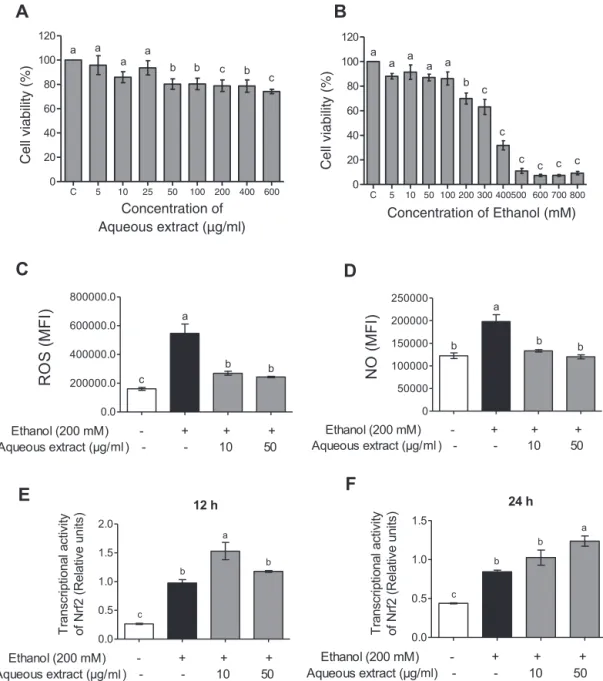

TheresultsofFig.2(panelA)showedthattherewasno sig-nificantdifferenceintheHepG2cellsviabilityatconcentrationsof 5–25g/mlofaqueousextractofB.trimera,withviability

main-tained above85%. In theconcentrations of50–600g/ml there

wasasignificantreductioninviabilityinrelationtothecontrol, butmaintainedabove75%.InpanelBasignificantreductionwas

observed in cell viability from theconcentration of 200M of

ethanol.

Baccharistrimeraaqueousextractdecreasedareactivespecies productioninHepG2cellsincubatedwithethanol

ItcanbeobservedinFig.2thatethanolpromotedtheincrease

ofROS(panelC)and NO(panelD)inHepG2cells.Therewasa

reductionintheseparameterswhenthecellswerepretreatedwith aqueousextractinbothconcentrations(10and50g/ml),reaching similarlevelstonegativecontrol(cellsnotincubatedwithethanol).

BaccharistrimeraaqueousextractmodulatesNrf2 transcriptionalactivityinHepG2cells

ItcanbeobservedinFig.2thattheethanolisabletoinducethe Nrf2transcriptionalactivityin12h(panelE)and24h(panelF)of incubation,whencomparedtothecontrol.TheNrf2transcriptional activitywasincreasedwhencellswerepretreatedwith10g/ml ofaqueousextractofB.trimera,in12h,whencompared tothe ethanolgroupwithouttreatment.Whereasregardingthe24h,the concentrationof50g/mlofaqueousextractwasabletoinduce theincreasetheNrf2transcriptionalactivity.

EvaluationoftheeffectofBaccharistrimeraonbiochemical parametersinalcoholichepatotoxicity

Renalfunctionwasevaluatedbasedontheparameters

creati-nineandurea.Inordertoevaluateliverfunction,theparameters ALT,ASTandtotalproteinwereused.Totalcholesterol,HDL,

frac-tionnon-HDLandtriacylglycerollevelsweredeterminedforthe

lipidprofile.Table3showedtheincreaseincreatininelevels,total

Table3

Biochemicalmarkerlevelsinserumandplasmaofrats.Animalsreceivedabsolute ethanol(E);pretreatmentwithaqueousextract(Aq)and1hafterreceivedabsolute ethanol.Control(C)receivedwater.Differentletters(a,b,c,d)indicatesignificant differencefromeachotheratp<0.05,whilesamelettersindicatenosignificant difference(p>0.05).

Biochemicalparameters Treatedgroups

C E Aq

Urea(mg/dl) 59.6±1.7 71.81±5.5 70.92±6.1

Creatinine(mg/dl) 0.375±0.09b 0.7361±0.087a 0.57±0.079a

ALT 18.99±1.4a 21.83±2.02a 12.0±0.65b

AST 37.02±3.8 37.76±3.5 27.5±2.69

Totalprotein(mg/dl) 5.97±0.65a 4.12±0.17b 4.62±0.4b

Glucose(mg/dl) 100.6±5.8 108.5±6.7 103.1±10.4

Totalcholesterol(mg/dl) 97.15±2.6c 230.0±28.24a 144.0±19.11b

HDL(mg/dl) 43.8±4.05 35.82±0.31 42.92±1.18

FractionnonHDL(mg/dl) 58.8±10.61c 189.1±20.95a 99.98±25.82b

Triacylglycerides(mg/dl) 63.95±12.72 53.86±6.49 53.22±12.78

cholesterolandnon-HDLfraction,besidesadecreaseintotal

pro-teininthegroupofanimalsthatreceivedethanol.Pretreatment

withaqueousextractofB.trimerapromotedadecreaseinALT

activ-ity,totalcholesterolandnon-HDLfractionandanincreaseintotal

protein,comparedwithethanolgroup.Itwasnotobserved

sig-nificantdifferencesinurealevels,ASTactivity,glucose,HDLand

triacylglycerideslevelsinanyoftheexperimentalgroups.

EffectofBaccharistrimeraontheantioxidantsysteminalcoholic hepatotoxicity

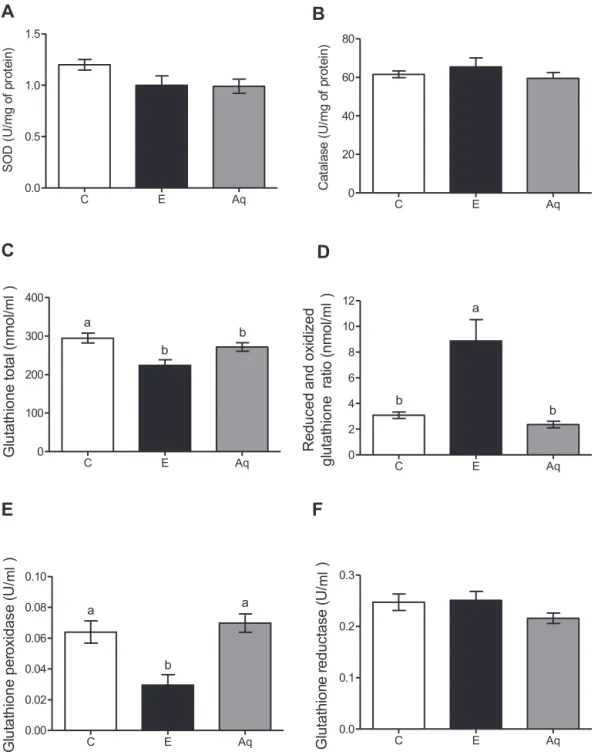

It couldbeobserved inFig. 3that theethanol consumption

didnotaltertheactivitiesofSOD(panelA)andcatalase(panel B)enzymes,comparedwithcontrolgroup.Theaqueousextractdid notaltertheseparameterseither.Regardingglutathionesystem, theresultsshowedasignificantdecreaseinglutathionetotal(panel C)and glutathioneperoxidase(GPx)activity(panelE),together withanincreaseinreduced/oxidizeglutathioneratio(panelD)in ethanolgroupwhencomparedwithcontrolgroup.B.trimera aque-ousextractpromotesanincreaseinGPxactivityandadecreasein reduced/oxidizeglutathioneratio.Glutathionereductaseactivity (panelF)didnotalterinanyoftheexperimentalgroups.

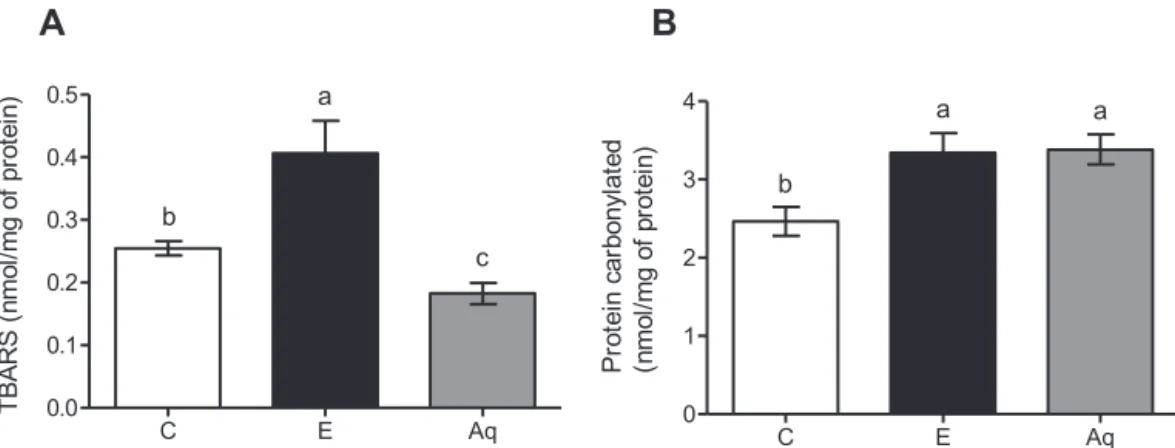

EvaluationoftheeffectofBaccharistrimeraonmarkersof oxidativestressinalcoholichepatotoxicity

InethanolgrouptherewasanincreaseinTBARS(Fig.4–panel A)andcarbonylatedprotein(panelB)levels,comparedtocontrol group.TheextractofB.trimerawasabletoreduceonlythelevelsof TBARS,noalterationswereobservedinthelevelsofcarbonylated protein.

BaccharistrimeradecreasestheMMP-2activityinalcoholic hepatotoxicity

ToevaluatetheMMP-2activitythezymographytechnicwas

used.Fig.5Arepresentsqualitativeimagesof geland5B repre-sentsthequantitativeactivity(banddensity).Then,itwasobserved

thatethanolpromotedanincreaseinMMP-2activity,when

com-paredtothecontrol.ThetreatmentwithB.trimerapromotesthe reductionofMMP-2activity,inrelationofethanolgroup.

Baccharistrimeraaqueousextractreducesmicro-steatosisin alcoholichepatotoxicity

Fig.2.CellviabilityofBaccharistrimeraaqueousextract(5–600g/ml)(A)andethanol(5–800mM)(B)for24hmeasuredbyMTTassay.EffectofBaccharistrimeraaqueous extractonethanol-inducedROS(C)andNO(D)production,expressionMFI(Mediumintensityoffluorescence).WealsoevaluatedtheeffectofBaccharistrimeraon ethanol-inducedNuclearfactorE2-relatedfactor2(Nrf2),vialuciferaseassay,for12h(E)and24h(F).Theresultswereexpressedasmean±S.D(n=6).Differentletters(a,b,c) indicatesignificantdifferencefromeachotheratp<0.05,whilesamelettersindicatenosignificantdifference(p>0.05).

withB.trimerawasabletoreducethedegreeofseverityofthe microvesicularsteatosis,mainlygrade1.

Discussion

Thepresentstudyinvestigatedthepotentialprotectiveeffects ofB. trimeraaqueousextract againsthepatotoxicity inducedby ethanol,aswellthecompoundspresentinthisextract.Invitro, abil-ityoftheextracttoscavengefreeradicalsandtheeffectofB.trimera onethanolmediatedROS,NOandtranscriptionalactivityofNrf2in HepG2cellswereexamined.Itwasprovidedforthefirsttimethat B.trimeraaqueousextractstimulatesthetranscriptionalactivityof Nrf2.Invivo,usingaratmodelofacuteintoxicationbyethanol, itwasdemonstratedthatB.trimeraalleviatedtheoxidative

dam-ages,improvingtheantioxidantdefenseandattenuatinghepatic

steatosis(Graphicabstract).Thisencouragestheadvancementof researchindicatingB.trimeraastherapeuticagentfor hepatopro-tection.

Flavonoids, caffeic acid derivatives and diterpenes have

been isolated from different extracts of B. trimera (Abad and

Bermejo, 2007; Verdi et al., 2005; Lívero et al., 2016a,b).

In our study, using LC-DAD-ESI-MS three flavonoids were

detectedinaqueousextract(apigenin-6,8-di-C-glucopyranosidium (7);6(8)-C-furanosyl-8(6)-C-hexosylflavone(10);6(8)-C -hexosyl-8(6)-C-furanosyl flavone (11)) and twelve phenolic acids (3-O-feruloylquinic acid (1); 4-O-caffeinoylquinic acid (2); 5-O-caffeinoylquinic acid (3); 3-O-caffeoyylquinic acid (4); 4-O-feruloylquinic acid (5); 5-O-feruloylquinic acid (6); 3-O -isoferuloylquinicacid(8);5-O-isoferuloylquinicacid(9); 3,4-di-O-caffeinylquinic acid (12); 3,5-di-O-caffeoyylquinic acid (13); 4,5-di-O-caffeinoylquinic acid (14); 4-O-isoferuloylquinic acid (15)).

TheabilityofaqueousextractofB.trimeratosequesterradicals wasevaluatedandtheresultsshowedthatalltestedconcentrations

showedanantioxidantcapacityinadose-dependentmanner.For

Fig.3.EffectofBaccharistrimeraaqueousextractonthelevelofSOD(A),catalase(B),glutathionetotal(C),reducedandoxidizedglutathioneratio(D),activityofglutathione peroxidase(E)andglutathionereductase(F),intheliversofrats.Control(C)receivedwater.Animalsreceivedabsoluteethanol(E);pretreatmentwithaqueousextract(Aq) and1hafterreceivedabsoluteethanol.Differentletters(a,b)indicatesignificantdifferencefromeachotheratp<0.05,whilesamelettersindicatenosignificantdifference (p<0.05).

intheotherinvitroassays,HepG2cellswereincubatedwith differ-entconcentrationsoftheaqueousextractandethanol.Theresults

showedthatB.trimeraaqueousextractwasnotcytotoxicatany

concentrationevaluated.Rodriguesetal.(2009)demonstratedthat

theaqueousB.trimeraextractwasnotcytotoxictobonemarrow

cellsatanyoftheconcentrationstested(500–2000g/ml). How-ever,Nogueiraetal.(2011)demonstratedtheaqueousextractwas cytotoxicin500g/mlinHTCandHEKcells(rathepatomacells andhumanembryokidneyepithelialcells,respectively) indicat-ingthatthetoxicitymaybetissue-specific.Inrelationtoethanol, therewasareductioninviabilityfrom200mM.Kumaretal.(2012) observedasignificantdecreaseinHepG2cellsviabilityexposedto ethanolfrom100mM.Basedonthis,non-cytotoxicconcentrations

ofB.trimerawereselected(10–50g/ml)andtheethanolcytotoxic

concentration(200mM)wereusedinthesubsequentexperiments.

WhenHepG2cellswereincubatedwithethanolthe

produc-tionofROSandNOwasincreased.Haorahetal.(2011)alsofound

increasedROSandNOinendothelialcellstreated withethanol.

Thisincreasecanbeexplainedbythefactthatthemainmetabolite

ofethanol,acetaldehyde,activatesNADPHoxidaseandinducible

nitricoxidesynthase(iNOS),whichleadstoanincreaseinthe

pro-ductionofEROandnitricoxide(NO),causingoxidativedamages

(Haorahetal.,2008;Rumpetal.,2010;Alikunjuetal.,2011).Gong andCederbaum(2006)observedthatinhepatocytesisolatedfrom ratstherewasanincreaseofNrf2,probablyduetotheinduction

Fig.4. EffectofBaccharistrimeraaqueousextractonthelevelofTBARS(A)andcarbonylatedprotein(B)intheliversofrats.Control(C)receivedwater.Animalsreceived absoluteethanol(E);pretreatmentwithaqueousextract(Aq)and1hafterreceivedabsoluteethanol.Differentletters(a,b)indicatesignificantdifferencefromeachother atp<0.05,whilesamelettersindicatenosignificantdifference(p<0.05).

Fig.5.EffectofBaccharistrimeraaqueousextractontheMMP-2activity,viagelatin zymography,intheliversofrats.A:Gelbands;B:banddensity.HT1080fibrosarcoma cellswereusedaspositivecontrol.Control(C)receivedwater.Animalsreceived absoluteethanol(E);pretreatmentwithaqueousextract(Aq)and1hafterreceived absoluteethanol.Differentletters(a,b)indicatesignificantdifferencefromeach otheratp<0.05,whilesamelettersindicatenosignificantdifference(p<0.05).

ROSproduction,withconsequentactivationofNrf2.Thesefindings areinagreementwithourresultsthatfoundanincreaseinNrf2 transcriptionalactivityincellsthatreceivedonlyethanol.Ethanol inducedNrf2transcriptionalactivityhasalsobeendemonstrated byothersauthors(Dongetal.,2011;Luetal.,2012).

ThepretreatmentwithB.trimerapromotedthereductionofROS andNO,returningtovaluessimilartothecontrol.Antioxidantscan actdirectlythroughtheeliminationofEROandERN,orindirectly, throughthemodulationofsignalingpathways(Paivaetal.,2015). Thus,thisstudyandothersshowedthatB.trimerahastheability tosequesterradicals,inferringthatthedecreaseinthesespecies canbeattributed,atleast,totheplant’sdirectactiondeOliveira etal.,2012;Páduaetal.,2013).Inaddition,itwasalsoinferred thatthisdecreasecanbeattributedtotheindirectaction,sinceB. trimeraaqueousextractpromotedanincreaseinNrf2 transcrip-tionalactivity,promotingantioxidantprotectionagainstthestress bytheethanol.Líveroetal.(2016a,b)havealreadydemonstrated thatthehydroethanolicextractofB.trimerapromotesanincrease expressionofNrf2,butnootherstudyhasshowntheeffectofB. trimeraovertheNrf2activity.Thus,thesedatainagreementwith thedecreaseofROSandNOshowthatB.trimeramaybeeffective inpreventingstressinducedbyethanol.

Fig.6.Representativehematoxylinandeosin-stainedhistologicalsectionsoflivers fromrats(A).Semi-quantificationwasdemonstratedinB.Severemicrovesicular steatosiswasobservedintheethanolgroup(E),butnotinthecontrolgroup(C).

Baccharistrimeraaqueousextract(Aq)attenuatedfataccumulationinhepatocytes. Theimageswerephotographedat400xmagnification.Scalebar=50m.Asterisk (*)indicatessignificantdifferencebetweentwogroups.

Toconfirmtheeffectsaninvivoexperimentwascarriedout,

wheretheanimalsreceivedonlyabsoluteethanol orwere

pre-treated with B. trimera aqueous extract. The results showed a

worsening kidney function, decrease in total protein, but ALT

and AST transaminases did not change in the ethanol group.

There are several situations in which there is loss of

correla-tionbetweenserumlevelsofliverenzymesandatissue injury,

sothatanincrease ofserumactivitiesof liverenzymemarkers

doesnotnecessarilyreflectonlivercelldeath(Contreras-Zentella andHernández-Mu˜noz,2016).However,acetaldehydeformed

dur-ing the metabolism of ethanol may form adducts with amino

acids,reflectingthegeneraldecreaseinproteinsynthesisandthe decreaseofplasmaproteinsecretion(Smithetal.,2007). Pretreat-mentwithB.trimera significantlydecreasedALTactivity.Lívero etal. (2016a,b)alsofounda decreased ALT activitywhenmice receivedhydroethanolicextract ofB.trimera.Theacute

glucoseconcentration,thisdifferencecanbeexplainedbythe nutri-tionalstatus at thetime alcohol isadministered (Steineretal., 2015).Probablebecauseouranimalsreceivedbalanced

commer-cialfeednochangeswerefoundinglucoseinanyexperimental

group.

Theresultsalsoshowedanincreaseintotalcholesterol,

non-HDL fraction, beyond hepatic micro-steatosis, but TAG did not

changeinethanolgroup.Afteracuteconsumptionofhighdosesof ethanoltheserumlevelsofTAGmayincrease,decreaseorremain normal,however,thetotal flow thatisabsorbed bytheliveris increasedduetothestimulatoryeffectsofethanolonliverblood

flow(BaraonaandLieber,1979),promotingtheaccumulationof

micro and/or macrovesicles lipids in hepatocytes (Baraona and

Lieber,1979;LíveroandAcco,2016).B.trimeraimprovedthelipid profileanddecreasedhepaticmicro-steatosis,protectingagainst ethanoldamage.Líveroetal.(2016a,b)showedthat hydroethano-licextractofB.trimeradecreasestheexpressionoftheScd1gene, whichisresponsibleforencodingthestearoyl-CoAdesaturase-1,

animportantenzymeinthebiosynthesisofthemainfattyacids

foundinTAG.Maybepartofthismechanism contributestothe

protectionmechanismbytheextract.

Theabilityofethanoltoinduceoxidativestressandantioxidant depletion,suchasglutathione,iswellrecognized(Luand Ceder-baum,2008; Hanetal.,2016).Our resultsshowedthat ethanol alterationsinglutathionemetabolismweremoresignificantthan alterationsin SODand CATactivities,sinceethanol-treatedrats exhibitedadecreaseinGPxactivityanddecreaseinoxidized glu-tathione,reflectinganincreaseintheGSH/GSSGglutathioneratio. ThedecreaseinGPxactivityinethanol-inducedintoxicationhas

also been demonstrated in other studies (Park et al., 2013; Li

etal.,2014; Yanet al.,2014).GPxisone oftheresponsiblefor thereductionofH2O2 towater, sinceadecreasein theactivity ofthisenzymewasobserved,itispossibletoinferthatinthese animalstherewasprobablyaccumulationofH2O2,contributingto oxidativestress.Thisinefficiencyintheantioxidantresponsemay justifytheincreaseintheTBARSandcarbonylatedproteinlevels observedinourstudy.Incarbontetrachloride-induced hepatotox-icitymodelsithasbeenshownthatthedecreaseofglutathioneis

relatedtotheincrease ofMDA(Azabetal.,2013;Al-Sayedand

Abdel-Daim,2014) B. trimera promotedincreased GPx activity,

contributingtoanadaptiveresponsewithaconsequentdecrease

in TBARS. In fact, themechanisms involved in the antioxidant

capacityofpolyphenolsincludethesuppressionofROSformation byinhibitionoftheenzymesinvolvedintheirproduction;direct eliminationofROS;orpositiveregulationinantioxidantdefense (Hussainetal.,2016).

Hepaticfibrosisisanimportanthistologicalfeatureassociated withtheprogression ofalcoholicliverdisease,characterizedby

increaseddepositionofextracellularmatrix components(ECM).

The key event in liver fibrogenesis is the activation of hepatic stellatecells(HSC),whichareamajorsourceofECMintheliver (Cenietal.,2014;Lasek,2016).Acetaldehydeisoneofthemain

mediators of alcohol-inducedfibrogenesis, as it may stimulate

the synthesis of fibrillar collagens and structural glycoproteins

ofECM.AcetaldehydemayfurtherpromoteECMremodelingby

upregulationofmetalloproteinase-2(MMP-2)(Cenietal.,2014).

In addition, H2O2 due to oxidative stress can activate

MMP-2 (Hopps et al., 2015). This fact can explain the increase in

MMP-2 activity found in the ethanol treated animals in our

experiment.However,thepretreatmentwithB.trimeradecreased

the MMP-2 activity. It has already been shown that the

caf-feinoylquinicacidshaveMMP-2inhibitoryactivity(Benedeketal., 2007).Since that in the characterization of ourextract it was

demonstrated the presence of caffeiolquinic acids, it is

possi-ble toinferthat this mechanismis involved withtheobserved

protection.

Thus,whenourresultswereanalyzedalltogethersuggestthat B.trimeraaqueousextractappearstobepromisingastherapeutic agentforhepatoprotection.

Authorcontributions

ACSRelaboratedandperformedallthework.GRA,GHBSGCB

contributed in collecting plant sample and identification,

con-fectionof herbarium,chromatographic analysis.KPL andPHAM

assisted in thepractical laboratorypart.CMA contributed with

the zymography technique. BMS, ACAC and EMCR contributed

withluciferaseassay.WGLcontributedwithhistologicalanalyses.

DCCdesignedthestudy,supervisedthelaboratoryworkand

con-tributedtocriticalreadingofthemanuscript.Alltheauthorshave readthefinalmanuscriptandapprovedthesubmission.

Conflictsofinterest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

ThisworkwassupportedbyFundac¸ãodeAmparoàPesquisado

EstadodeMinasGerais,CNPqandUniversidadeFederaldeOuro

Preto(PROPP/UFOP),Brazil.

References

Abad,M.J.,Bermejo,P.,2007.Baccharis(Compositae):areviewupdate.Arkivoc7, 76–96.

Aebi,H.,1984.Catalaseinvitro.MethodEnzymol.105,121–126.

Alikunju,S.,AbdulMuneer,P.M.,Zhang,Y.,Szlachetka,A.M.,Haorah,J.,2011.The inflammatoryfootprintsofalcohol-inducedoxidativedamageinneurovascular components.BrainBehav.Immun.25,129–136.

Al-Sayed,E.,Martiskainen,O.,Seifel-Din,S.H.,Sabra,A.N.,Hammam,O.A., El-Lakkany,N.M.,Abdel-Daim,M.M.,2014.Hepatoprotectiveandantioxidanteffect ofBauhiniahookeriextractagainstcarbontetrachloride-inducedhepatotoxicity inmiceandcharacterizationofitsbioactivecompoundsby HPLC-PDA-ESI-MS/MS.Biomed.Res.Int.,http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/245171.

Al-Sayed, E., Abdel-Daim, M.M., Kilany, O.E., Karonen, M., Sinkkonen, J., 2015. Protective role of polyphenols from Bauhinia hookeri against car-bontetrachloride-inducedhepato-andnephrotoxicityinmice.Ren.Fail.37, 1198–1207.

Al-Sayed,E.,Abdel-Daim, M.M.,2014.Protective roleofcupressuflavonefrom Cupressus macrocarpa against carbon tetrachloride-induced hepato- and nephrotoxicityinmice.PlantaMed.80,1665–1671.

Araújo,C.M.,Lúcio,K.P.,EustáquioSilva,M.,Isoldi,M.C.,BiancodeSouza,G.H., Brandão,G.C.,Schulze,R.,Costa,D.C.,2015.Morusnigraleafextractimproves glycemicresponseandredoxprofileintheliverofdiabeticrats.FoodFunct.6, 3490–3499.

Azab,S.S.,Abdel-Daim,M.,Eldahshan,O.A.,2013.Phytochemical,cytotoxic, hepato-protectiveandantioxidantpropertiesofDelonixregialeavesextract.Med.Chem. Res.22,4269–4277.

Bandeira,A.C.B.,Silva,R.C.,RossoniJúnior,J.V.,Figueiredo,V.P.,Talvani,A.,Cangussú, S.D.,Bezerra,F.S.,Costa,D.C.,2017.Lycopenepretreatmentimproves hepatotox-icityinducedbyacetaminopheninC57BL/6mice.Bioorg.Med.Chem.Lett.25, 1057–1065.

Baraona,E.,Lieber,C.S.,1979.Effectsofethanolonlipidmetabolism.J.LipidRes.20, 289–315.

Benedek, B., Kopp,B., Melzig, M.F., 2007.Achillea millefoliums.l. is the anti-inflammatoryactivitymediatedbyproteaseinhibition?J.Ethnopharmacol.113, 312–317.

Bianchi,M.L.P.,Antunes,L.M.G.,1999.Radicaislivreseosprincipaisantioxidantes dadieta.Rev.Nutr.12,123–130.

Buege,J.Á.,Aust,S.D.,1978.Microsomallipidperoxidation.MethodEnzymol.52, 302–310.

Bona,C.M.,Biasi,L.A.,Zanette,F.,Nakashima,T.,2005.Estaquiadetrêsespéciesde Baccharis.Cienc.Rural.35,223–226.

Brunt,E.M.,Janney,C.G.,DiBisceglie,A.M.,Neuschwander-Tetri,B.A.,Bacon,B.R., 1999.Nonalcoholicsteatohepatitis:aproposalforgradingandstaging histolog-icallesions.Am.J.Gastroenterol.94,2467–2474.

Cederbaum,A.I.,2012.Alcoholmetabolism.Clin.LiverDis.16,667–685. Ceni,E.,Mello,T.,Galli,A.,2014.Pathogenesisofalcoholicliverdisease:roleof

oxidativemetabolism.WorldJ.Gastroenterol.20,17756–17772.

Contreras-Zentella,M.L.,Hernández-Mu˜noz,R.,2016.Isliverenzymereleasereally associatedwithcellnecrosisinducedbyoxidantstress?Oxid.Med.CellLongev., http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/3529149.

deAraújo,G.R.,Rabelo,A.C.S.,Meira,J.S.,Rossoni-Júnior,J.V.,deCastro-Borges, W.,Guerra-Sá, R.,Batista,M.A., Silveira-Lemos,D.,Souza, G.H.B.,Brandão, G.C., Chaves, M.M., Costa, D.C., 2016. Baccharis trimera inhibits reactive oxygen species production through PKC and down-regulation p47phox phosphorylation of NADPH oxidase in SK Hep-1 cells. Exp. Biol. Med., http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1535370216672749.

Ding,R.B.,Tian,K.,Huang,L.L.,He,C.W.,Jiang,Y.,Wang,Y.T.,Wan,J.B.,2012.Herbal medicinesforthepreventionofalcoholicliverdisease:areview.J. Ethnophar-macol.144,457–465.

Dong,J.,Yan,D.,Chen,S.,2011.StabilizationofNrf2proteinbyD3Tprovides pro-tectionagainstethanol-inducedapoptosisinPC12cells.PLoSONE6,e16845, http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016845.

El-Naga,R.,2015.Apocyninprotectsagainstethanol-inducedgastriculcerinratsby attenuatingtheupregulationofNADPHoxidases1and4.Chem.Biol.Interact. 242,317–326.

Foglio,M.A.,Queiroga,C.L.,Sousa,I.M.O.,Rodrigues,R.A.F.,2006.PlantasMedicinais comoFontedeRecursosTerapêuticos:UmModeloMultidisciplinar. Multiciên-cia,Availableat:http://www.multiciencia.unicamp.br/art047.htm[assessed 30.09.17].

Fahmy,N.M.,Al-Sayed,E.,Abdel-Daim,M.M.,Singab,A.N.,2017.Anti-inflammatory andanalgesicactivitiesofTerminaliamuelleriBenth.(Combretaceae).DrugDev. Res.78,146–154.

Fotakis,G.,Timbrell,J.A.,2005.Invitrocytotoxicityassays:comparisonofLDH, neu-tralred,MTTandproteinassayinhepatomacelllinesfollowingexposureto cadmiumchloride.Toxicol.Lett.160,171–177.

Gong,P.,Cederbaum,A.I.,2006.Nrf2isincreasedbyCYP2E1inrodentliverand HepG2cellsandprotectsagainstoxidativestresscausedbyCYP2E1.J.Hepatol. 43,144–153.

González,J.A.M.,Madrigal-Santillán,E.,Morales-González,A.,Bautista,M., Gayosso-Islas,E.,Sánchez-Moreno,C.,2015.Whatisknownregardingtheparticipation offactorNrf-2inliverregeneration?Cell4,169–177.

Han,K.H.,Hashimoto,N.,Fukushima,M.,2016.Relationshipsamongalcoholic liverdisease,antioxidants,andantioxidantenzymes.WorldJ.Gastroenterol. 7,37–49.

Haorah,J.,Ramirez,S.H.,Floreani,N.,Gorantla,S.,Morsey,B.,Persidsky,Y.,2008. Mechanismofalcohol-inducedoxidativestressandneuronalinjury.FreeRadic. Biol.Med.45,1542–1550.

Haorah,J.,Floreani,N.A.,Knipe,B.,Persidsky,Y.,2011.Stabilizationof superox-idedismutasebyacetyl-l-carnitineinhumanbrainendotheliumduringalcohol exposure:novelprotectiveapproach.FreeRadic.Biol.Med.51,1601–1609. Hernández,J.A.,López-Sánchez,R.C.,Rendón-Ramírez,A.,2015.Lipidsandoxidative

stressassociatedwithethanol-inducedneurologicaldamage.Oxid.Med.Cell Longev.,http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/1543809.

Hopps,E.,LoPresti,R.,Montana,M.,Canino,B.,Calandrino,V.,Caimi,G.,2015. Analysisofthecorrelationsbetweenoxidativestress,gelatinasesandtheir tis-sueinhibitorsinthehumansubjectswithobstructivesleepapneasyndrome.J. Physiol.Pharmacol.66,803–810.

Hussain,T.,Tan,B.,Yin,Y.,Blachier,F.,Tossou,M.C.,Rahu,N.O.,2016.Oxidativestress andinflammation:whatpolyphenolscandoforus?Oxid.Med.CellLongev., http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/7432797.

Karam,T.K.,Dalposso,L.M.,Casa,D.M.,deFreitas,G.B.L.,2013.Carqueja( Baccha-ristrimera):utilizac¸ãoterapêuticaebiossíntese.Rev.Bras.PlantasMed.15, 280–286.

Kim, J., Keum, Y.S., 2016. NRF2, a key regulator of antioxidants with two faces towards cancer. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev., http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1155/2016/2746457.

Kumar,S.K.J.,Liao,J.W.,Xiao,J.H.,Gokila-Vani,M.,Wang,S.Y.,2012. Hepatoprotec-tiveeffectoflucidoneagainstalcohol-inducedoxidativestressinhumanhepatic HepG2cellsthroughtheup-regulationofHO-1/Nrf-2antioxidantgenes.Toxicol. InVitro26,700–708.

Lasek,A.W.,2016.Effectsofethanolonbrainextracellularmatrix:implicationsfor alcoholusedisorder.AlcoholClin.Exp.Res.40,2030–2042.

Levine,R.L.,Williams,L.A.,Stadtman,E.R.,Shacter,E.,1994.Carbonylassaysfor determinationofoxidativelymodifiedproteins.MethodEnzymol.233,346–357. Li,M.,Lu,Y.,Hu,Y.,Zhai,X.,Xu,W.,Jing,H.,Tian,X.,Lin,Y.,Gao,D.,Yao,J., 2014.SalvianolicacidBprotectsagainstacuteethanol-inducedliverinjury through SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of p53 in rats. Toxicol. Lett. 228, 67–74.

Lívero,F.A.,Acco,A.,2016.Molecularbasisofalcoholicfattyliverdisease:from incidencetotreatment.Hepatol.Res.46,111–123.

Lívero,F.A.,Martins,G.G.,QueirozTelles,J.E.,Beltrame,O.C.,PetrisBiscaia,S.M., Cav-icchioloFranco,C.R.,OudeElferink,R.P.,Acco,A.,2016a.Hydroethanolicextract ofBaccharistrimeraamelioratesalcoholicfattyliverdiseaseinmice.Chem.Biol. Interact.260,22–32.

Lívero,F.A.R.,daSilva,L.M.,Ferreira,D.M.,Galuppo,L.F.,Borato,D.G.,Prando,T.B., Lourenc¸o,E.L.,Strapasson,R.L.,Stefanello,M.É.,Werner,M.F.,Acco,A.,2016b. HydroethanolicextractofBaccharistrimerapromotesgastroprotectionand heal-ingofacuteandchronicgastriculcersinducedbyethanolandaceticacid. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’sArch.Pharmacol.389,985–998.

Lowry,O.H.,Rosenbrough,N.J.,Farr,A.L.,Randall,R.J.,1951.Proteinmeasurement withthefolinphenolreagent.J.Biol.Chem.193,265–275.

Lu,Y.,Zhang,X.H.,Cederbaum,A.I.,2012.EthanolinductionofCYP2A5:roleof CYP2E1-ROS-Nrf2pathway.Toxicol.Sci.128,427–438.

Lushchak,V.I.,2014.Freeradicals,reactiveoxygenspecies,oxidativestressandits classification.Chem.Biol.Interact.224,164–175.

Marklund,S.,Marklund,G.,1974.Involvementofthesuperoxideanionradicalinthe autoxidationofpyrogallolandaconvenientassayforsuperoxidedismutase.Eur. J.Biochem.47,469–474.

Nogueira,N.P.,Reis,P.A.,Laranja,G.A.,Pinto,A.C.,Aiub,C.A.,Felzenszwalb,I.,Paes, M.C.,Bastos,F.F.,Bastos,V.L.,Sabino,K.C.,Coelho,M.G.,2011.Invitroandinvivo toxicologicalevaluationofextractandfractionsfromBaccharistrimerawith anti-inflammatoryactivity.J.Ethnopharmacol.138,513–522.

Oliveira,A.C.P.,Endringer,D.C.,Amorim,L.A.S.,Brandão,M.G.L.,Coelho,M.M.,2011. EffectoftheextractsandfractionsofBaccharistrimeraandSyzygiumcuminion glycaemiaofdiabeticandnon-diabeticmice.J.Ethnopharmacol.102,465–469. deOliveira,C.B.,Comunello,L.N.,Lunardelli,A.,Amaral,R.H.,Pires,M.G.,daSilva, G.L.,Manfredini,V.,Vargas,C.R.,Gnoatto,S.C.,deOliveira,J.R.,Gosmann,G.,2012. PhenolicenrichedextractofBaccharistrimerapresentsanti-inflammatoryand antioxidantactivities.Mol.Cells17,1113–1123.

Pádua,B.C.,Silva,L.D.,RossoniJúnior,J.V.,Humberto,J.L.,Chaves,M.M.,Silva,M.E., Pedrosa,M.L.,Costa,D.C.,2010.AntioxidantpropertiesofBaccharistrimerain theneutrophilsofFisherrats.J.Ethnopharmacol.129,381–386.

Pádua,B.P.,RossoniJunior,J.V.,deBritoMagalhaes,C.L.,Seiberf,J.B.,Araujo,C.M., BiancodeSouza,G.H.,Chaves,M.M.,Silva,M.E.,Pedrosa,M.L.,Costa,D.C.,2013. BaccharistrimeraimprovestheantioxidantdefensesystemandinhibitsiNOS andNADPHoxidaseexpressioninaratmodelofinflammation.Curr.Pharm. Biotechnol.14,975–984.

Pádua,B.C.,RossoniJúnior,J.V.,Magalhães,C.L.B.,Chaves,M.M.,Silva,M.E.,Pedrosa, M.L.,BiancodeSouza,G.H.,Brandão,G.C.,Rodrigues,I.V.,Lima,W.G.,Costa, D.C.,2014.ProtectiveeffectofBaccharistrimeraextractonacutehepaticinjury inamodelofinflammationinducedbyacetaminophen.MediatorsInflamm., http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/196598.

Paiva,F.A.,Bonomo,L.F.,Boasquivis,P.F.,Paula,I.T.B.R.,Guerra,J.,Leal,W.M.,Silva, M.E.,Pedrosa,M.L.,Oliveira,R.P.,2015.Carqueja(Baccharistrimera)protects againstoxidativestressandamyloid-inducedtoxicityinCaenorhabditis ele-gans.Oxid.Med.CellLongev.,http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/740162. Park,H.Y.,Choi,H.D.,Eom,H.,Choi,I.,2013.Enzymaticmodificationenhancesthe

protectiveactivityofcitrusflavonoidsagainstalcohol-inducedliverdisease. FoodChem.139,231–240.

Rates,S.M.K.,2001.Plantsassourceofdrugs.Toxicon39,603–613.

Rodrigues,C.R.F.,Dias,J.H.,Semedo,J.G.,daSilva,J.,Ferraz,A.B.F.,Picada,J.N.,2009. MutagenicandgenotoxiceffectsofBaccharisdracunculifolia(D.C.).J. Ethnophar-macol.124,321–324.

Rump,T.J.,AbdulMuneer,P.M.,Szlachetka,A.M.,Lamb,A.,Haorei,C.,Alikunju, S.,Xiong,H.,Keblesh,J.,Liu,J.,Zimmerman,M.C.,Jones,J.,DonohueJr.,T.M., Persidsky,Y.,Haorah,J.,2010.Acetyl-L-carnitineprotectsneuronalfunction fromalcoholinducedoxidativedamageinthebrain.FreeRadic.Biol.Med.49, 1494–1504.

Silva,B.M.,Sousa,L.P.,Ruiz,A.C.G.,Leite,F.G.G.,Teixeira,M.M.,Fonseca,F.G.,Pimenta, P.F.P.,Ferreira,P.C.P.,Kroon,E.G.,Bonjardim,C.A.,2011.Thedenguevirus non-structuralprotein1(NS1)increasesNF-jBtranscriptionalactivityinHepG2cells. Arch.Virol.156,1275–1279.

Smith,C.,Smith,C.,Lieberman,M.,Marks,A.D.,2007.BioquímicaMédicaBásicade Marks,2nded.,pp.458–471.

Steiner,J.L.,Crowell,K.T.,Lang,C.H.,2015.Impactofalcoholonglycemiccontroland insulinaction.Biomol.Ther.5,2223–2246.

Verdi,L.G.,Brighente,I.M.C.,Pizzolatti,M.G.,2005.GêneroBaccharis(Asteraceae): aspectosquímicos,econômicosebiológicos.Quim.Nova28,85–94.

Lu,Y.,Cederbaum,A.I.,2008.CYP2E1andoxidativeliverinjurybyalcohol.FreeRadic. Biol.Med.44,723–738.