Changes in lower dental arch dimensions and tooth

alignment in young adults without orthodontic treatment

Bruno Aldo Mauad1, Robson Costa Silva1, Mônica Lídia Santos de Castro Aragón2, Luana Farias Pontes2, Newton Guerreiro da Silva Júnior3, David Normando4

How to cite this article: Mauad BA, Silva RC, Aragón MLSC, Pontes LF, Sil-va Júnior NG, Normando D. Changes in lower dental arch dimensions and tooth alignment in young adults without orthodontic treatment. Dental Press J Orthod. 2015 May-June;20(3):64-8.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2176-9451.20.3.064-068.oar

Submitted: June 29, 2014 - Revised and accepted: October 01, 2014

Contact address: David Normando

Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém, Brazil. Rua Augusto Corrêa, no 1, CEP: 66.075-110

E-mail: davidnormando@hotmail.com 1 Specialist in Orthodontics, ABO-PA, Belém, Pará, Brazil.

2 MSc in Orthodontics, Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA), School of

Dentistry, Belém, Pará, Brazil.

3 Adjunct professor, Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA), School of Dentistry,

Belém, Pará, Brazil.

4 Adjunct professor, Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA), School of Dentistry,

Belém, Pará, Brazil. Coordinator, Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA), postgraduate program in Dentistry. Coordinator, ABO-PA, specialization program in Orthodontics. Belém, Pará, Brazil.

» The authors report no commercial, proprietary or financial interest in the prod-ucts or companies described in this article.

Objective: The aim of this longitudinal study, comprising young adults without orthodontic treatment, was to assess spontaneous changes in lower dental arch alignment and dimensions. Methods: Twenty pairs of dental casts of the lower arch, obtained at different time intervals, were compared. Dental casts obtained at T1 (mean age = 20.25) and T2 (mean age = 31.2) were compared by means of paired t-test (p < 0.05). Results: There was significant reduction in arch dimensions: 0.43 mm for intercanine (p = 0.0089) and intermolar (p = 0.022) widths, and 1.28 mm for diagonal arch length (p < 0.001). There was a mild increase of ap-proximately 1 mm in the irregularity index used to assess anterior alignment (p < 0.001). However, regression analysis showed that changes in the irregularity index revealed no statistically significant association with changes in the dental arch dimensions (p > 0.05). Furthermore, incisors irregularity at T2 could not be predicted due to the severity of this variable at T1 (p = 0.5051). Conclusion: Findings suggest that post-growth maturation of the lower dental arch leads to a reduction of dental arch dimensions as well as to a mild, yet significant, increase in dental crowding, even in individuals without orthodontic treatment. Furthermore, dental alignment in the third decade of life cannot be predicted based on the severity of dental crowding at the end of the second decade of life.

Keywords:Malocclusion. Dental arch. Mandible. Maxillofacial development. Dental crowding. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2176-9451.20.3.064-068.oar

Objetivo: o objetivo deste trabalho foi avaliar, por meio de um estudo longitudinal em adultos jovens, sem tratamento ortodôntico, as alterações espontâneas do alinhamento da arcada dentária inferior e de suas dimensões. Métodos: vinte pares de modelos de gesso da arcada inferior foram obtidos em dois tempos. No primeiro exame (T1), os indivíduos tinham, em média, 20,25 anos; enquanto no segundo exame (T2) a média de idade foi de 31,2 anos. Comparações entre os tempos T1 e T2 foram realizadas usando o teste t pareado (p < 0,05). Resultados: houve uma redução significativa nas dimensões da arcada — de 0,43mm nas larguras intercaninos (p = 0,0089) e intermolares (p = 0,022) e de 1,28mm para o comprimento diagonal da arcada (p < 0,001). Foi observado um aumento suave, de aproximadamente 1mm, no índice de irregularidade anterior (p < 0,001). Entretanto, a análise de regressão mostrou que as mudanças no índice de irregularidade não revelaram uma associação estatisticamente significativa com as mudanças na arcada dentária (p > 0,05). Além disso, o índice de irregularidade dos incisivos em T2 não pode ser estimado, devido à severidade dessa variável em T1 (p = 0,5051).

Conclusão: esses achados sugerem que a maturação da arcada dentária inferior, pós-crescimento, leva a uma redução das dimensões da arcada e um aumento suave, porém significativo, do apinhamento dentário, mesmo em indivíduos sem tratamento ortodôntico. Assim, o alinhamento dentário na terceira década de vida não pode ser previsto tendo como base a severidade do apinhamento dentário ao final da segunda década de vida.

INTRODUCTION

Changes in the dental arch should be assessed to identify etiological factors associated with tertiary crowding, a phase when there is an increase in the demand of adult patients for orthodontic treatment or retreatment.

Numerous longitudinal studies have been con-ducted to assess changes in dental arch aligment,1-5 especially in the lower arch where the most signiicant post-treatment changes occur.6 Changes in the irst two decades of life have already been widely stud-ied;1,4,7,8 however, there is lack of knowledge about occlusal changes in adults, particularly spontaneous changes in subjects without orthodontic treatment.

The literature shows diferent opinions about the etiology of lower incisors crowding, consider-ing reduction in arch perimeter as the main causal factor. Other authors also point out the presence of a third molar9 or multiple factors.4

As regards adults, clinical studies oten report orthodontically treated cases,10-13 thereby hindering evaluation of physiological changes in dental alignment. Thus, analysis of untreated cases is an excellent oppor-tunity to determine the physiological changes in dental alignment, in addition to being the key to plan the re-tention phase and the removal timing for retainers.

This study aims to assess spontaneous changes in lower dental arch dimensions and incisors align-ment by means of a longitudinal investigation con-ducted with young adults without previous orth-odontic treatment.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study was approved by Universidade Federal do Pará Institutional Review Board (CEP-ICS/UFPA) under protocol #366.357/2013.

The sample comprised 20 young adults (9 males and 11 females ) with mean age of 20.25 years old (15-24 years). Their records were retrieved from a previous study14 assessing 40 subjects, most of which were university undergraduate students. Eleven years later (T2), 20 individuals with a mean age of 31.75 years were reassessed. Most subjects who were not reassessed at T2 had moved away. Therefore, the inal sample was smaller. Dental casts were obtained for all subjects at T1 and T2 (n = 20). Only the lower dental arch was measured.

In selecting the sample, the following inclusion criteria were applied: no missing teeth or history of extractions in the lower arch, and no orthodontic or prosthodontic treatment carried out during the ob-servation period.

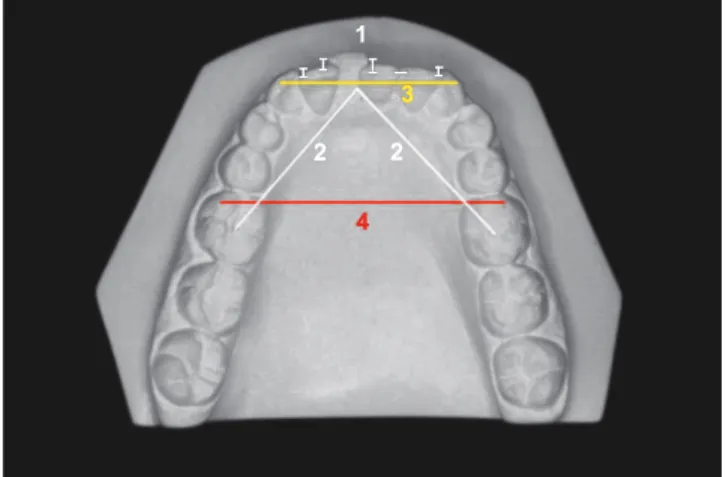

All measurements (Fig 1) were performed by a single previously calibrated operator, and repeated ater a three-day interval by means of a digital caliper (Utustools/Concepción, Chile) with precision of 0.02 mm. Whenever irst and second measurements difered in more than 0.3 mm, they were retaken. Mean was used for statistical analysis.

The following measurements were investigated: Little’s irregularity index,15 dental arch length, inter-canine and intermolar widths (Fig 1). Little’s irregu-larity index was the sum, expressed in millimeters, of the linear displacements of ive contact points in lower incisors region. Arch length was obtained as the dis-tance from lower inter-incisors region, at the level of palatal papilla, to the center of the irst molar on both sides. Intercanine width was measured as the maxi-mum distance between the cusp tips of lower canines; and intermolar width was measured as the greatest dis-tance between the mesiobuccal cusp tips of lower irst permanent molars.

Statistical analyses were performed by means of BioEstat 5.3 sotware (Mamirauá Institute, Belém, Pará, Brazil). Data were submitted to analysis of normal

Figure 1 - Irregularity index (1), arch length (2), intercanine width (3) and intermolar width (4).

1

2 2

3

Table 2 - Regression analysis of changes in Little’s index at T2-T1 (dependent variable) and the following independent variables: intercanine width (IcW), intermolar width (ImW), Little’s index (LI) at T1 and total arch length (TAL).

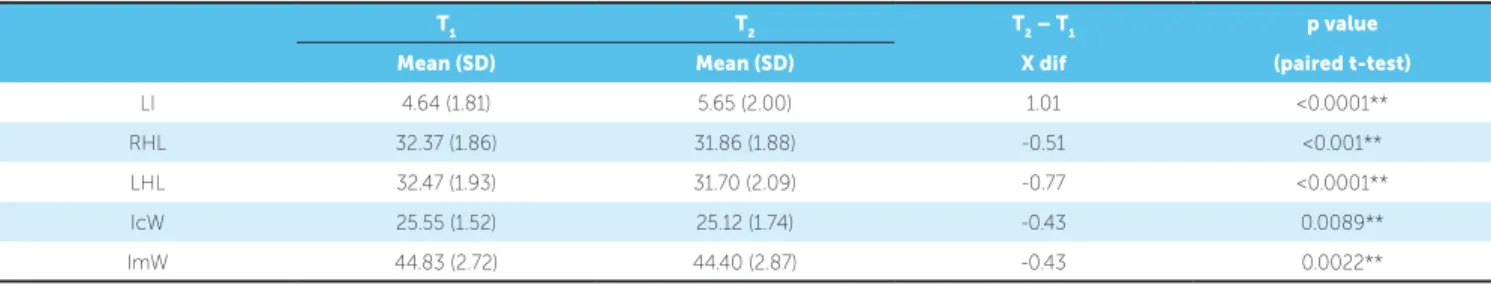

Table 1 - Mean, standard deviation (SD) and p value for each measurement at T1 (initial examination) and T2 (11.5 years later).

LI = Little’s index; RHL = Right hemiarch length; LHL = Left hemiarch length; IcW = Intercanine width; ImW = Intermolar width.

T1 T2 T2 – T1 p value

Mean (SD) Mean (SD) X dif (paired t-test)

LI 4.64 (1.81) 5.65 (2.00) 1.01 <0.0001**

RHL 32.37 (1.86) 31.86 (1.88) -0.51 <0.001**

LHL 32.47 (1.93) 31.70 (2.09) -0.77 <0.0001**

IcW 25.55 (1.52) 25.12 (1.74) -0.43 0.0089**

ImW 44.83 (2.72) 44.40 (2.87) -0.43 0.0022**

Independent

variables IcW T1 ImW T1 LI T1 TAL

F p value

Dependent

variable R

2 p value R2 p value R2 p value R2 p value

LI T2-T1 0.73 0.3179 14.5 0.0869 0.01 0.1938 10.35 0.1636 1.29 0.3179

distribution by D’Agostino-Pearson test. T1 and T2 were compared by means of paired t-test at p < 0.05. Additionally, multiple regression analysis investigated whether increase in lower incisors irregularities could be predicted on the basis of initial data (T1).

RESULTS

Data had normal distribution; therefore, to assess the diferences between T1 and T2, paired t-test was used.

From T1 to T2, there was an increase of 1.01 mm in Little’s index (p < 0.0001). All other measurements were smaller at T2 (Table 1): arch length on the right side (-0.51 mm, p < 0.001) and let side (-0.77 mm, p < 0.0001), intercanine width (-0.43 mm, p < 0.0089) and intermolar width (-0.43 mm, p < 0 .0022).

Regression analysis revealed that none of the in-dependent variables were statistically associated with changes observed in Little’s index (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Dental arches are subjected to dimensional changes throughout life.5,11,16,17 Many studies have investigated orthodontic treatment stability by as-sessing the morphological changes of dental arch ater the retention phase.17-20 These changes justify relapse of dental crowding in the lower dental arch. However, it is a challenge to determine whether

these dimensional changes would be a relapse of orthodontic treatment or a result of dental arch maturation. Identifying risk factors that could pre-dict these changes is also important.

There is some evidence showing that the mor-phological and dimensional changes observed in dental arches ater orthodontic treatment also occur in individuals who were not submitted to it.3,4,6,16,20 Nevertheless, in these cases, changes occur on a smaller degree than they do in samples of orthodon-tically treated cases.4 These studies assessed changes occurring in the second decade of life. Changes ater this age have been poorly investigated.

The presence of third molars and their inlu-ence on crowding provokes controversy among dentists.9 Some studies identiied a positive rela-tionship between third molars and this malocclu-sion;5 however, several studies have refuted the hy-pothesis that the third molar exerts inluence over crowding.21 Therefore, this issue did not receive major attention in the present study.

in previous research, in which there were no reports of severe degrees of lower incisors irregularity.3,4,6,22

As regards lower dental arch morphology, interca-nine width showed a reduction greater than 0.3 mm in 11 out of 20 subjects, with a mean of 0.43 mm (p < 0.001), thereby corroborating the results of previous studies4,6,23,24 examining other age groups. Sinclair and Little4 found a decrease in intercanine width of 0.44 mm from 13-14 years to 19-20 years, whereas Bishara et al24 found a decrease of 0.5 mm for male subjects and 0.6 mm for female subjects aged be-tween 26 and 45 years old. On the other hand, Har-ris,25 ater conducting a longitudinal assessment of individuals aged between 20 and 54 years old, did not ind changes in intercanine width. Richardson and Gormley,22 ater a 10-year follow-up of adults aged between 18 and 28 years old, found that changes in intercanine width were minor.

The present study corroborates the decrease in lower dental arch length during childhood,4,7,8,25,27 adolescence,4,7,23 and adulthood3,6,22 reported in pre-vious studies (Table 1). Total reduction in arch length was 1.28 mm, 0.51 mm on the right side (p < 0.001) and 0.77 mm on the let side (p < 0.001).

Intermolar width showed a statistically signiicant (p = 0.0022) average decrease of 0.43 mm (Table 1). This is the most controversial measurement in the lit-erature, particularly because while some studies found no signiicant diferences,1,3,4,7,23,24 others observed an increase in intermolar width when assessing adoles-cents and young adults.6,22,25 This divergence is prob-ably due to methodological diferences, especially with regard to the age range of research subjects.

In this paper, regression analysis revealed that in-creased crowding in the third decade of life could not be predicted by any variable examined at the end of the second decade, neither based on arch dimensions nor Little’s index. Similar indings have been report-ed for the upper arch in an adolescent sample.28

Another study presented untreated subjects who had higher or lower degree of dental crowding in the lower arch in a irst evaluation, and showed similar indings in the second evaluation. Assessments were carried between the age of 15 and 20 years;20 there-fore, severity of initial irregularity would not cause the subject to have a worse prognosis of crowding in the future. However, a longer evaluation period is re-quired to conirm the results.

Dental crowding is a progressive feature of aging. Examining untreated subjects is key to understand the changes that occur during natural aging. Physi-ological changes in the morphology of dental arches seem to occur throughout life, but our results sug-gest that these changes are milder ater the second de-cade of life. Scientiic evidence is required to identify which factors actually inluence this process.

CONCLUSIONS

Lower dental arch dimensions tend to minor, but signiicant, decrease from 20 to 30 years of age, whereas dental crowding increases in an average of 1 mm during this period.

1. Lundström A. Changes in crowding and spacing of the teeth with age. Dent Pract Dent Rec. 1969;19(6):218-24.

2. Knott VB. Longitudinal study of dental arch widths at four stages of dentition. Angle Orthod. 1972;42(4):387-94.

3. Bishara SE, Treder JE, Damon P, Olsen M. Changes in the dental arches and dentition between 25 and 45 years of age. Angle Orthod. 1996;66(6):417-22. 4. Sinclair PM, Little RM. Maturation of untreated normal occlusions. Am J Orthod.

1983;83(2):114-23.

5. Little RM, Wallen TR, Riedel RA. Stability and relapse of mandibular anterior alignment irst pre molar extraction cases treated by traditional edgewise orthodontics. Am J Orthod. 1981;80(4):349-65.

6. Tsiopas N, Nilner M, Bondemark L, Bjerklin K. A 40 years follow-up of dental arch dimensions and incisor irregularity in adults. Eur J Orthod. 2013;35(2):230-5. 7. JH Sillman. Dimensional changes of the dental arches: Longitudinal study from

birth to 25 years. Am J Orthod. 1964;50(11):824-42.

8. Louly F, Nouer PR, Janson G, Pinzan A. Dental arch dimensions in the mixed dentition: a study of Brazilian children from 9 to 12 years of age. J Appl Oral Sci. 2011;19(2):169-74.

9. Prasad K, Hassan S. Inluence of third molars on anterior crowding - revisited. J Int Oral Health. 2011;3(3):37-40.

10. de la Cruz A, Sampson P, Little RM, Artun J, Shapiro PA. Long-term changes in arch form after orthodontic treatment and retention. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1995;107(5):518-30.

11. Rossouw PE, Preston CB, Lombard CJ, Truter JW. A longitudinal evaluation of the anterior border of the dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1993;104(2):146-52.

12. Castro RCFR, Freitas MR, Janson G, Freitas KMS. Correlação entre o índice morfológico das coroas dos incisivos inferiores e a estabilidade da correção do apinhamento ântero-inferior. Rev Dental Press Ortod Ortop Facial. 2007;12(3):47-62.

13. Erdinc AE, Nanda RS, Işiksal E. Relapse of anterior crowding in patients treated with extraction and nonextraction of premolars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(6):775-84.

14. Silva Júnior NG, Normando ADC, Prado SRL. O Apinhamento do arco dentário inferior e seu relacionamento com o diâmetro mésio-distal dentário, dimensões do arco e sexo. R Soc Br Ortodon. 1990;1(6):172-6.

REFERENCES

15. Little RM. The irregularity index: a quantitative score of mandibular anterior alignment. Am J Orthod. 1975;68(5):554-63.

16. Jonsson T, Magnusson TE. Crowding and spacing in the dental arches: long-term development in treated and untreated subjects. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2010;138(4):384e1-7

17. Myser SA, Campbell PM, Boley J, Buschang PH. Long-term stability: postretention changes of the mandibular anterior teeth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2013;144(3):420-9.

18. Dyer KC, Vaden JL, Harris EF. Relapse revisited: again. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;142(2):221-7.

19. Maia NG, Normando AD, Maia FA, Ferreira MA, Alves MS. Factors associated with orthodontic stability: a retrospective study of 209 patients. World J Orthod. 2010;11(1):61-6.

20. Freitas KM, Janson G, Tompson B, Freitas MR, Simão TM, Valarelli FP, et al. Posttreatment and physiologic occlusal changes comparison. Angle Orthod. 2013;83(2):239-45.

21. Karasawa LH, Rossi AC, Groppo FC, Prado FB, Caria PH. Cross-sectional study of correlation between mandibular incisor crowding and third molars in young Brazilians. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18(3):e505-9.

22. Richardson ME, Gormley JS. Lower arch crowding in the third decade. Eur J Orthod. 1998;20(5):597-607.

23. Paulino V, Paredes V, Cibrian R, Gandia JL. Dental arch changes from adolescence to adulthood in a Spanish population: a cross-sectional study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16(4):e607-13.

24. Bishara SE, Jakobsen JR, Treder J, Nowak A. Arch width changes from 6 weeks to 45 years of age. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;111(4):401-9. 25. Harris EF. A longitudinal study of arch size and form in untreated adults. Am J

Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;111(4):419-27.

26. Sampson WJ, Richards LC. Prediction of mandibular incisor and canine crowding changes in the mixed dentition. Am J Orthod. 1985;88(1):47-63.

27. Foster TD, Grundy MC. Occlusal changes from primary to permanent dentitions. Br J Orthod. 1986;13(4):187-93.