www.jped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Prevalence

and

factors

associated

with

smoking

among

adolescents

夽

,

夽夽

Marilyn

Urrutia-Pereira

a,b,

Vinicius

J.

Oliano

c,

Carolina

S.

Aranda

d,

Javier

Mallol

e,

Dirceu

Solé

d,∗aUniversidadeFederaldoPampa(UNIPAMPA),Uruguaiana,RS,Brazil

bPontifíciaUniversidadeCatólicadoRioGrandedoSul(PUC-RS),PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil cUniversidadedaRegiãodaCampanha(URCAMP),Alegrete,RS,Brazil

dUniversidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo(UNIFESP),EscolaPaulistadeMedicina(EPM),DepartamentodePediatria,SãoPaulo,RS,

Brazil

eUniversidadedeSantiagodoChile(USACH),HospitalCRSElPino,DepartamentodeMedicinaRespiratóriaPediátrica,Santiago,

Chile

Received12April2016;accepted13July2016 Availableonline22November2016

KEYWORDS

Tobacco; Adolescent;

Riskfactors;

Cigarette

Abstract

Objective: Despite anti-smoking prevention programs, many adolescents start smoking at schoolage.Themainobjectivesofthisstudyweretodeterminetheprevalenceandriskfactors associatedwithsmokinginadolescentslivinginUruguaiana,RS,Brazil.

Methods: Aprospectivestudywasconductedinadolescents(12---19years),enrolledin munic-ipalschools,whoansweredaself-administeredquestionnaireonsmoking.

Results: 798adolescentswereenrolledinthestudy,withequaldistributionbetweengenders. Thetobaccoexperimentation frequency(evertriedacigarette, evenoneortwo puffs)was 29.3%; 14.5% started smokingbefore 12 years ofage and13.0% reportedsmoking atleast onecigarette/daylastmonth.Havingasmokingfriend(OR:5.67,95%CI:2.06---7.09),having cigarettesofferedbyfriends(OR:4.21,95%CI:2.46---5.76)andhavingeasyaccesstocigarettes (OR:3.82,95%CI:1.22---5.41)wasidentifiedasfactorsassociatedwithsmoking.Havingparental guidanceonsmoking(OR:0.67,95%CI:0.45---0.77),havingnocontactwithcigarettesathome inthelastweek(OR: 0.51,95%CI:0.11---0.79)andknowingaboutthedangersofelectronic cigarettes(OR:0.88,95%CI:0.21---0.92)wereidentifiedasprotectionfactors.

夽 Pleasecitethisarticleas:Urrutia-PereiraM,OlianoVJ,ArandaCS,MallolJ,SoléD.Prevalenceandfactorsassociatedwithsmoking

amongadolescents.JPediatr(RioJ).2017;93:230---7.

夽夽StudycarriedoutatEscolaPaulistadeMedicina(EPM),UniversidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo(UNIFESP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:dirceu.sole@unifesp.br(D.Solé). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2016.07.003

Conclusion: TheprevalenceofsmokingamongadolescentsinUruguaianaishigh.The imple-mentationofmeasurestoreduce/stoptobaccouseanditsnewformsofconsumption,suchas electroniccigarettesandhookah,areurgentandimperativeinschools.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/ 4.0/).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Tabaco; Adolescente;

Fatoresderisco;

Cigarro

Prevalênciaefatoresassociadosaotabagismoentreadolescentes

Resumo

Objetivo: Apesardosprogramasdeprevenc¸ãoantitabagista,muitosadolescentescomec¸ama fumarnaidadeescolar.Foramobjetivosdoestudodeterminaraprevalênciaeosfatoresde riscoassociadosaoconsumodetabacoemadolescentesmoradoresdomunicípiodeUruguaiana RS,Brasil.

Métodos: Estudotransversal, realizado em adolescentes de12 a 19 anos, matriculados em escolasdomunicípio,queresponderamquestionárioautoaplicávelsobretabagismo.

Resultados: Participaram798adolescentescomigualdistribuic¸ãoentreosgêneros.A frequên-ciadeexperimentac¸ãodetabaco(Algumaveztentoufumarumcigarro,mesmoqueumaou duastragadas)foi29,3%,sendoque14,5%comec¸aramfumarantesdos12anosdevidae13,0% delesafirmaramterem fumadopelomenosumcigarro/dianoúltimomês. Foram identifica-doscomoassociadosaotabagismo:teramigotabagista(OR:5,67,IC95%:2,06-7,09),teroferta decigarropeloamigo(OR:4,21,IC95%:2,46-5,76)efacilidadedeconseguircigarros(OR:3,82, IC95%:1,22-5,41).Terorientac¸õesdospaissobretabagismo(OR:0,67,IC95%:0,45-0,77),nãoter contatocomcigarroemcasanaúltimasemana(OR:0,51,IC95%:0,11-0,79)esaberosmalefícios docigarroeletrônico(OR:0,88,IC95%:0,21-0,92)foramidentificadoscomodeprotec¸ão. Conclusões: A prevalência de tabagismo entre os adolescentes de Uruguaiana é alta. A implantac¸ãode medidasnasescolaspara reduzirouacabaroconsumo detabacoedesuas novasmodalidades,comooscigarroseletrônicoseonarguilééurgenteeimperiosa.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigo OpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4. 0/).

Introduction

Tobaccouseistheleadingpreventablecauseofdeathand

diseases worldwide and it is estimated that in the 21st

century, one billion people will die becauseof smoking.1

Approximately80%ofsmokersintheworldliveincountries with low and/or medium income, where the burden of tobacco-relateddiseaseshasagreatimpact.2

Atotalof11%ofdeathsfromischemicheartdiseaseand 70%ofdeathsfromlung,bronchial,andtrachealcancerare attributedtotobaccouse.Itisbelievedthattheincreased prevalenceofsmokingobservedindevelopingcountriesover the years will be responsible for a two-fold increase in theoverloadofhealthcarefornon-communicablediseases.3

Therefore,itisnecessarytoestablishanefficientand sys-tematicsurveillancemechanismtomonitorthetrendsofuse oftobaccoanditsderivatives.4

An international collaborative study of schoolchildren from131countriesshowedthatadolescentsarethegroup with the highest risk for smoking initiation, since the overallprevalence ofschoolchildrenwhoareactive smok-ers was 8.9%, being higher in the Americas (17.5%) and Europe (17.9%), and less than 10% in other assessed regions.5

In Brazil, the National School-Based Health Sur-vey (Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar [PeNSE])

documented that 30% of young individuals aged between 13and15 startedsmokingbefore12yearsof age.6 Ithas

beenreportedthathabitsacquiredatthisstageoflifeare usuallykeptatadulthoodandaredifficulttomodify,7and

thatalthoughadolescentshaveknowledgeoftherisksthat areinvolvedintheconsumption oftobaccoandits deriva-tives, theirhabits seem tobedivergent.8 Itis during the

transitionyears,duringhighschoolandcollege/university, thattobaccouse starts,aswell asgreater stabilizationof smokingbehavior.9

Forthisreason,overthepastdecades,theschool envi-ronmenthasbeenthefocusofspecificeffortstoinfluence thebehaviorofadolescents,byusingappropriate interven-tionstohelpthemavoidtobaccouseatsuchanearlystage intheirlives.10,11

Thus,consideringtheconsumptionofcigarettesby ado-lescentsasariskbehaviortotheirhealthandthatalthough arecentBrazilianstudy12showedareductioninthe

preva-lenceofsmokingamongyoungindividuals,particularlythose ina vulnerable socio-economiccondition, smoking among adolescentsitisstillamajorchallengeinthecityof Urugua-iana,stateofRioGrandedoSul,Brazil.

Methods

Studydesign

ProspectivestudycarriedoutbetweenMarchandJune2015

inthecityofUruguaiana,RS,whosepopulationisestimated

at125,435inhabitants,ofwhich6%areattheagerangeof

thestudy,i.e.,12---19years.13

Ofthe66 schoolsinthe municipality(31municipal,32 state, and three private schools) 51 were excluded (31 municipaland20stateschools)asthestudentsenrolledin these schools were not at the age range assessed in the study.Of the 15 remaining schools, eight were randomly selectedforthestudy.Duringthesecondphase,classes con-tainingstudentsattheagegroupassessedinthestudywere randomly selected in each school and the students were invitedtoparticipate.

Samplesizecalculation

The sample size calculation was performed using these

parameters: prevalence of 10% for tobacco consumption

withaconfidencelevelof95%andalphaerrorof5%,

result-ing in 750 students, plus 20% for eventual losses, which

resultedinafinalsampleof900students.

ThestudywasapprovedbytheEthicsCommitteeof

Hos-pitalSantaCasadeCaridadeofUruguaianaandwasgranted

permissiontocarryouttheresearchbytheDepartmentof

StateEducation andrespectiveprivateschools in

Urugua-iana.

All adolescents signed the free and informed consent

form,andthoseyounger than18 yearsalso hadthe form

signedbytheirparents/guardians.

Datacollection

The adolescents allowed to participate in the study

answeredtheself-administeredquestionnaireinthe

class-room,andduetoconfidentialityissues,wereidentifiedonly

byageandgender.Thequestionnaireswerefilledoutwith

thehelpofatrainedinvestigator(VJO,physicaleducation

teacher)presentintheclassroomatthattime.

The self-administered questionnaire used in the study

was the California Tobacco Survey,14 translated into

Por-tugueseandadaptedtotheBrazilian cultureaccording to international recommendations.15 The questionnaire was

independentlytranslatedintoPortuguese bytwoBrazilian physiciansspecializedinallergies(forwardtranslation).The two translations were compared by two other physicians and disagreements were eliminated after consensus. The productwasthentranslatedintoEnglishbyanative English-speaking translator (backward translation) and compared totheoriginalquestionnaire,withnorelevantdifferences found betweenthem. The final versionin Portuguese was administeredtoagroupofadolescentstoassesstheir under-standinganddifficultiesinansweringit,andafewlinguistic adaptationswereperformed(patienttesting).Afew adjust-mentsweremadeandthefinalversionofthequestionnaire wascompleted(Tables1and2).

The questionnaire consists of questions related to tobacco andsmoking, aswell as thoughts and knowledge on tobacco(Table 1) and exposure tosmoke from others (Table2),thesmokingstatusoffamilymembersandfriends, andknowledgeofhazardoussmokinghabits.

Theadolescentsthatsmokedcigarettesatsomepointin their lives(have youever tried smokingacigarette,even oneortwopuffs?)wereconsideredexperimentalsmokers. Adolescents whosmoked cigaretteson‘‘oneormoredays in thelastthirtydays’’wereconsidered currentsmokers, asrecommendedbytheCentersforDiseasePreventionand Control(CDC)andtheWorldHealthOrganization(WHO).15

Statisticalanalysis

Afterreviewingthereturnedquestionnaires,102were

dis-carded due to questionnaire completion errors and the

remaining 798 were analyzed. The obtained data were

transferred toan Excel spreadsheetfor further statistical

analysis. Considering smoking as the dependent variable,

the resultswereshown in relationtothe exposureor not

tosmoke,usingthechi-squaredorFisher’sexacttest.The

variablesidentifiedassignificant(p<0.05)wereusedinthe

logistic regression model (stepwise backward) and

signifi-cantdifferenceswereidentified.

Results

A total of 798 questionnaireswere adequately filled out,

withequaldistributionbygender,astheyweredistributed

inequalnumberstobothgendersineachclassroom.

According to the affirmative answer to the question

‘‘Haveyouevertriedacigarette,evenoneortwopuffs?’’

adolescents were characterized as ‘‘has tried smoking’’

(n=234), and the ones that answered no, as ‘‘never

smoked’’(n=564).

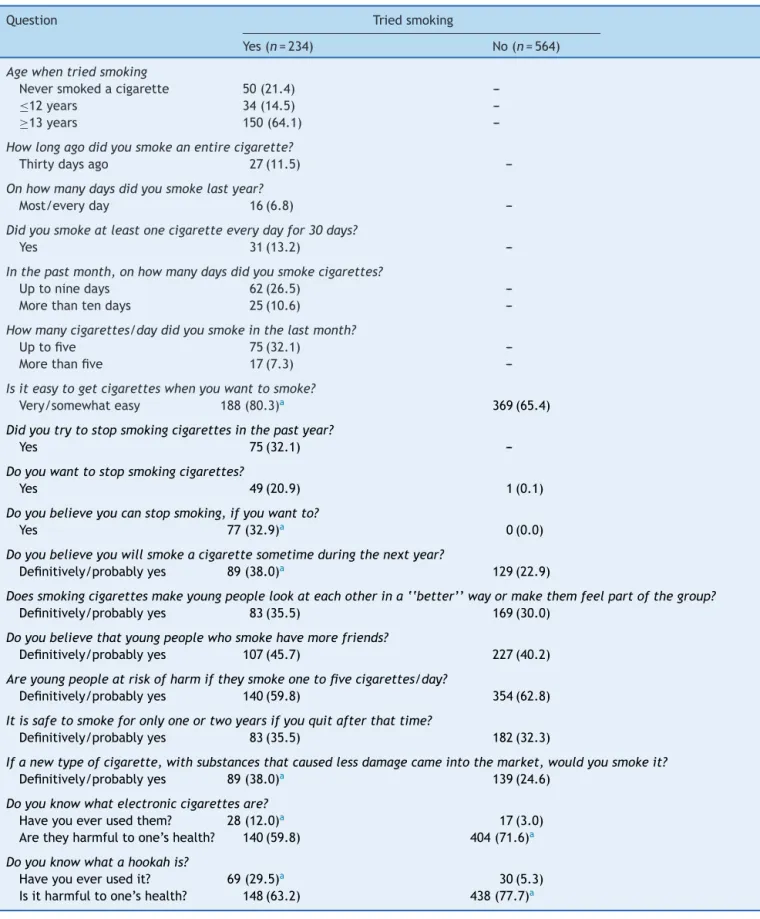

Table1summarizestheadolescents’answersregarding smoking. A total of 29.3% reported having tried smoking (234/798), whereas21.4% (50/234)reported neverhaving smoked an entirecigarette,14.5% startedsmokingbefore age12,and64.1%after13yearsold.

When asked about how long ago they had smoked an entire cigarette, 11.5% reported smoking in the last month(Table1).Although6.8%(16/234)oftheadolescents reportedhavingsmoked onmost daysor everyday inlast month, 13.2%(31/234) hadsmoked at least onecigarette every day and 32.1% (75/234) had smoked at least five cigarettesinthelast30days(Table1).Additionally,32.1% (75/234) reportedhavingtriedtoquitsmokingin thelast yearand32.9%(77/234)believed theycouldstopsmoking iftheywantedto(Table1).

Thecomparativeanalysisbetweenthetwogroups signif-icantlyshowedthat80.3%ofthosewhotriedsmokingsaid they thoughtit was very/somewhateasy tostop smoking iftheywantedto, 32.9%(77/234) believedtheywouldbe abletoquitsmokingiftheywantedto,and20.9%(49/234) reportedtheywantedtoquitsmoking.

Table1 Adolescents’answersregardingtobaccouseandthoughtsaboutit.

Question Triedsmoking

Yes(n=234) No(n=564)

Agewhentriedsmoking

Neversmokedacigarette 50(21.4)

---≤12years 34(14.5)

---≥13years 150(64.1)

---Howlongagodidyousmokeanentirecigarette?

Thirtydaysago 27(11.5)

---Onhowmanydaysdidyousmokelastyear?

Most/everyday 16(6.8)

---Didyousmokeatleastonecigaretteeverydayfor30days?

Yes 31(13.2)

---Inthepastmonth,onhowmanydaysdidyousmokecigarettes?

Uptoninedays 62(26.5)

---Morethantendays 25(10.6)

---Howmanycigarettes/daydidyousmokeinthelastmonth?

Uptofive 75(32.1)

---Morethanfive 17(7.3)

---Isiteasytogetcigaretteswhenyouwanttosmoke?

Very/somewhateasy 188(80.3)a 369(65.4)

Didyoutrytostopsmokingcigarettesinthepastyear?

Yes 75(32.1)

---Doyouwanttostopsmokingcigarettes?

Yes 49(20.9) 1(0.1)

Doyoubelieveyoucanstopsmoking,ifyouwantto?

Yes 77(32.9)a 0(0.0)

Doyoubelieveyouwillsmokeacigarettesometimeduringthenextyear?

Definitively/probablyyes 89(38.0)a 129(22.9)

Doessmokingcigarettesmakeyoungpeoplelookateachotherina‘‘better’’wayormakethemfeelpartofthegroup? Definitively/probablyyes 83(35.5) 169(30.0)

Doyoubelievethatyoungpeoplewhosmokehavemorefriends?

Definitively/probablyyes 107(45.7) 227(40.2)

Areyoungpeopleatriskofharmiftheysmokeonetofivecigarettes/day?

Definitively/probablyyes 140(59.8) 354(62.8)

Itissafetosmokeforonlyoneortwoyearsifyouquitafterthattime?

Definitively/probablyyes 83(35.5) 182(32.3)

Ifanewtypeofcigarette,withsubstancesthatcausedlessdamagecameintothemarket,wouldyousmokeit? Definitively/probablyyes 89(38.0)a 139(24.6)

Doyouknowwhatelectroniccigarettesare?

Haveyoueverusedthem? 28(12.0)a 17(3.0) Aretheyharmfultoone’shealth? 140(59.8) 404(71.6)a

Doyouknowwhatahookahis?

Haveyoueverusedit? 69(29.5)a 30(5.3) Isitharmfultoone’shealth? 148(63.2) 438(77.7)a

Chi-squared/Fisher’sexacttest.

a Significantlyhigherthantheothergroup.

cigarettesmadetheirpeerslookatthemina‘‘better’’way

ormadethemfeelpartofthegroupandthatsmokershad

more friends,although theyfeltthat smokingone tofive

cigarettesadaydidnotputthematriskandthatsmoking

forone totwoyearswould besafe,iftheystoppedafter

thisperiod(Table1).

Table2 Adolescents’answersrelatedtoexposuretootherpeople’ssmoking.

Question Triedsmoking

Yes(n=234) No(n=564)

Inthelastsevendays,onhowmanydayswereyouinthesameroomwithsomeonewhowassmokingcigarettes?

None 126(53.8) 435(77.1)a

Inthelastsevendays,onhowmanydayswereyouinanyroomofYOURHOMEwithsomeonewhowassmokingcigarettes?

None 151(64.5) 467(82.8)a

Inthelastsevendays,onhowmanydaysdidyoutravelinacarwithsomeonewhowassmokingcigarettes?

None 197(84.2) 515(91.3)a

Doyoubelievethatotherpeople’scigarettesmokingisharmfultoyou?

Definitively/probablyyes 132(56.4) 320(56.7)

Doesanyonewholiveswithyousmoke?

Yes 109(46.6)a 139(24.6)

Howmanyofyourfourclosestfriendssmokecigarettes?

None 98(41.9) 473(83.9)a

Ifanyofyourbestfriendsofferedyouacigarette,wouldyousmokeit?

Definitively/probablyyes 98(41.9)a 132(23.4)

Howdifficultwoulditbeforyoutorefuseorsay‘‘no’’ifafriendofferedyouacigarettetosmoke? Verydifficult/difficult 99(42.3) 210(37.2)

Whatpercentageofstudentsinyourgradehassmokedacigaretteatleastonceamonth?

None 88(37.6) 344(61.0)a

Upto20%(afew) 65(27.8) 124(22.0)

21---60%(some/half) 60(25.6)a 74(13.1)

>61%(most/almostall) 21(9.0)a 22(3.9)

Whichsentencebestdescribestherulesorregulationsrelatedtosmokinginsideyourhome? Smokingisnotallowedinsidethehouse 80(34.2) 267(47.3)a Smokingisallowedinsomeplaces/at

sometimes

36(15.4)a 39(6.9)

Smokingisnotallowedanywhereinmy house

44(18.8) 120(21.2)

Therearenorulesrelatedtosmokingin myhouse

74(31.6)a 138(24.5)

Hasoneofyourparents(orcaregivers)toldyounottosmokecigarettes?

Onlymymother(orfemalecaregiver) 47(20.1)a 70(12.4) Onlymyfather(ormalecaregiver) 42(17.9)a 39(6.9)

Both 140(59.8) 425(75.4)a

Neither 5(2.1) 30(5.3)

Chi-squared/Fisher’sexacttest.

ap<0.05---significantlyhigherthantheothergroup.

triedsmokingand 24.6%of thosewhodid notsmokesaid

theywouldusethem(Table1).Amongtheadolescentswho

triedsmoking,therewasasignificantlygreateraccountof knowledgeofelectroniccigarettesandhookahswhen com-pared tothose who never smoked; the use of electronic cigarettes and hookahs wasalso higher amongthose who hadtriedsmoking(Table1).Incontrast,amongthosewho hadneversmoked,therewasagreaterknowledgeofboth (electroniccigarettesandhookahs)beingharmfultohealth (Table1).

Regardingexposuretosmokefromotherpeople,itwas observed that those whotried smokingwere significantly moreexposedtootherpeople’stobaccosmokeathome,in thebedroom,orinthecar(Table2).Nevertheless,therewas

nosignificantdifferencebetweenthetwogroupsregarding thethoughtthatthesmokefromotherswouldcause dam-age:56.4% forthosewhohadtried smokingand56.7%for thosewhohadneversmoked(Table2).

Table3 Factorsidentifiedasrelatedtosmokinginadolescenceafterlogisticregressionanalysis.

Variables OR 95%CI p

Smokingamongtheclosestfriends 5.67 (2.06---7.09) <0.001 Cigaretteofferedbytheclosestfriend 4.21 (2.46---5.76) <0.001 Cigarettescanbeeasilyobtained 3.82 (1.22---5.41) <0.001 Smokingisnotallowedinsidethehouse 0.89 (0.17---1.11) 0.075 Harmfuleffectsofelectroniccigarettes 0.88 (0.21---0.92) <0.001

Harmfuleffectsofhookah 0.78 (0.32---1.48) 0.127

Parents’recommendationsaboutsmoking 0.67 (0.45---0.77) <0.001 Nosmokinginthehomeinthelastsevendays 0.51 (0.11---0.79) <0.001

OR,oddsratio;95%CI,95%confidenceinterval.

insidethehouse.Inbothgroups,thiscontrolisexercisedby

themotherand/orfather(Table2).

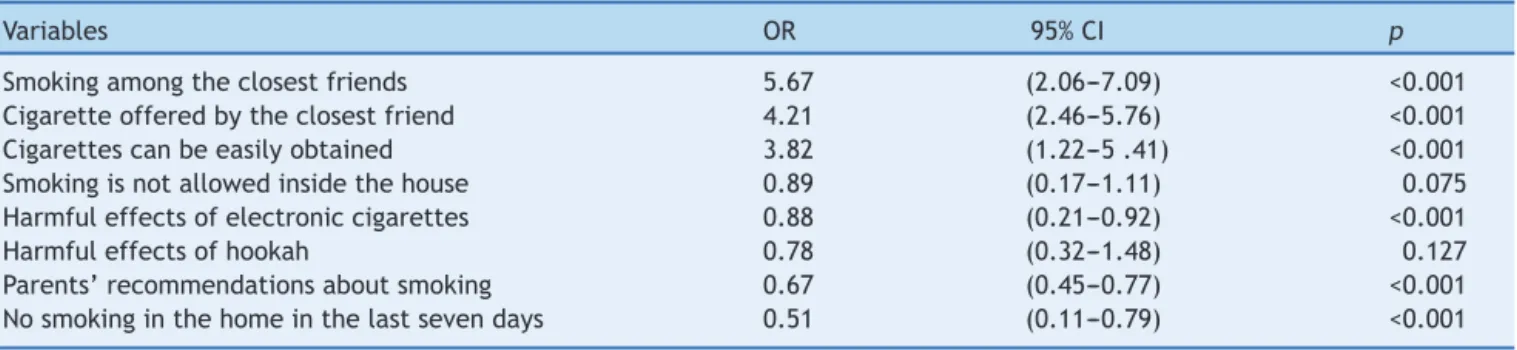

The variables identifiedassignificantlyassociatedwith smoking after the logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 3. The following were identified as risk factors forsmoking: havingfriendswhosmokes,havingcigarettes offeredbyfriends,andeasyaccesstocigarettes(Table3). Having parental guidance on smoking, not being exposed to smokingat home in the last week, and knowledge on theharmfuleffectsofelectroniccigaretteswereidentified asprotectivefactors(Table3).Thefactthat smokingwas not allowedinside thehome showed borderline value for significance.

Discussion

Adolescence is an important stage in life, when because

of thediscoveries, the concerns,the need toexplore the

unknown and venture without worrying about the

conse-quences,adolescentsoftenadoptriskybehaviors,including

cigarettesmoking.8However,although notalladolescents

whotrycigarettesbecomesmokers,experimentationisthe firststeptowardfutureadherencetoregularconsumption oftobaccoproducts.7

Thedefinitionofasmokerusedinthepresentstudywas theonerecommendedbytheWHO15andtheprevalenceof

smokingamongtheevaluatedadolescentswas37.2%,with 13.2%ofthemsmokingeveryday,higherthantherate pre-viouslyobservedinotherlocations.5Theserateswerelower

thanthoseamongthegeneralpopulationinseverallocations in Brazil(22.3---29.3%).16 However,theyweremuchhigher

thanthoseobservedinPortoAlegre:7.4%formenand9.1% inwomen.11

It is noteworthythat amongtheadolescentsevaluated here, 14.5% started cigarettesmoking before 12 yearsof ageand64.1%didsoaftertheageof13,similarlytowhat waspreviouslyobservedamongstudentsofthepublicschool system in ten Brazilian city capitals, showing that 11.6% ofstudentshadtriedsmokingbetween10and12yearsof age,17aswellasStudyofCardiovascularRisksinAdolescents

(ERICA)11where30%ofyoungindividualshadtriedsmoking

before12yearsandearlierthantheageobservedbyother authors.18

Earlyinitiationof tobaccouseis animportant prognos-tic factor for disease and should be avoided. The delay of afew yearsin thestart of consumption can reduceby

almosttwo-fold the risk of damagecaused by tobacco to health.6Ontheotherhand,itisshownthatwithincreasing

age,adolescentswhotrytobaccoanddonotinterruptthe habitbecometobaccousers,thusconsolidatingthehabitof smoking.7

The main factors associatedwithcigarette smokingby adolescentsevaluatedherewere:havingfriendswhosmoke and having cigarettes offered by friends, in addition to easyaccesstocigarettes(Table3).AlthoughinBrazilthere arelawsthat hindercigaretteaccessandconsumption by children and adolescents, such as the Child and Adoles-centStatute thatprohibitsthesale,supply,ordelivery of cigarettes to children or adolescents,19 the present data

confirmedthatthispracticehasnotbeenrespectedandit hasbeenidentifiedasariskfactorforsmoking,as80.3%of adolescentsmokersreportedeasyaccesstocigaretteswhen theywantedtosmoke(Table1).

However,onecannotblame exclusivelythelegal prod-ucttrade, asoneshouldconsidertheclandestinesales of cigarettes,such asthosethat arethe resultof smuggling andevenobtainingthemfromfriendsand/orrelativeswho smoke.Moreover,theroleofsocialnetworksininfluencing andstrengtheningsmokinghabitsis clear,which hasbeen increasinglystudiedandhasshownthathavingfriendswho smokeincreasesthe tolerance tothese habits, aswell as thepossibility of adoptingthem,20 identifiedas the main

risk factor for smoking among adolescents assessed here (Table3).ThesedataarecorroboratedbyaNorth-American study,which observed that non-smoking adolescents with friendswho smoked were morelikely tostart smokingin thefuturethanthosewhosefriendsdidnotsmoke.21

It is noteworthy that, although parental smoking was morefrequentamongadolescentsmokers(Table2),itwas not identified as a risk factor for current smoking. This is in contrast withthe observations of other studies that showthecriticalinfluenceofparentsonadolescent smok-ingbehavior. It is known that children aremore likely to reproducethebehaviorsandattitudesoftheirparents,who areconsidered by themas rolemodels;additionally, par-entswhosmokearemorelikelytoallowsmokinginsidethe house.22

Although there has been a reduction in smoking rates among parents, the same has not occurred among adolescents.23 Thissuggeststhattobaccocontrol

interven-tionsshouldbemorecomprehensiveandtargetedtoother influences, such as friends,20 school,9 visual media,24 or

toward the acquisition of new habits, such as the use of hookahs25orelectroniccigarettes,26withthelatterbeingan

importantinitiatingagentofsmoking,aswellasincreased taxrates.2

Thus, comparing the results observed in the ERICA11

and PeNSE-201227 studies, the prevalence of

experimen-tation was 18.5% vs. 19.6%, respectively, lower than the present result of 29.3%, and for current smoking, 5.7%

vs. 5.1%, against 13% among the present study’s adoles-cents.Nevertheless,onecannotruleoutthepossibilityof underreporting by the adolescents themselves, identified ascommonpracticein studies onsmoking. The low rates observedin thesenational studies11,27 possiblyreflectthe

country’spioneeringcomprehensivepolicies,whichhavea majorimpactonreducingtobaccouseamongyoung individ-uals,suchasthelegislationthatbannedsmokinginindoor public environments, the ban onadvertising in all media except at sales points, and the prohibition of misleading descriptors,suchas‘‘light’’or ‘‘ultra-light’’oncigarette packs.28

InthecityofUruguaiana(SouthBrazil),theresultswere different. The finding of higher prevalence rates in the Southcouldbe possiblydue tothe regioncultivationand production of tobacco, as well as a greater influence of Europeanmigrationthattraditionallyentails ahigh preva-lenceofsmokinghabits,whichcanbeperpetuatedthrough generations.11Toallthesefacts,onemustbeaddtheeasy

accesstocigarettes, suchasin the case of smuggling, as recentlyidentifiedinthecityofUruguaiana.29

It is importantthat anti-smokingeducational programs beencouragedinschools,sothatstudentsreceiveguidance andprofessionalhelp,especiallyforthosewhowanttoquit smoking.9,30Thedemandforspecializedhealthservices

out-sidetheschoolenvironmentcanresultinincreasedschool absenteeismand evenhindertheadolescents’accessand adherencetotheprograms.

These results reinforce theneed tostrengthen,at the municipalor statelevel,publicpoliciesaimedatreducing oreliminatingcontactofchildrenand/oradolescentswith cigarettes.Compliancewiththelawsrestrictingthesaleand consumptionofcigarettes,increasingthelegalageof pur-chase,promotinghealthy lifestyles,familyinvolvementin thepreventionofsmokinghabitprograms,priceincreases, implementationofanti-smokingprogramsinschools,aswell asappropriateguaranteedtreatmentsforsmokers,aresome ofthemeasuresthatcouldbeundertaken.

Pediatricians,beingthefirstprofessionalstocareforthe children,know theirenvironmentalexposure, followtheir development, and have a primary role as educators and promotersofhealthyhabits.

Although theconsequences ofsmokingareobserved in adulthood,itshouldbenotedthatthereductionor restric-tionof tobacco consumption in adolescence will have an educational impact on health and can reduce the possi-bilityof contactwithother restrictionsor illicit drugs, so it is essential for the physician to be attentive and well informed, and to participate in the development of new

approaches tofight againstsmoking, in anintegrated and interdisciplinarymanner.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.JhaP,PetoR. Globaleffects ofsmoking,ofquitting,and of takingtobacco.NEnglJMed.2014;370:60---8.

2.WorldHealthOrganizationWHOReportontheglobaltobacco epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland:WHO; 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/tobacco/globalreport/2015/en/ [cited 31.01.16].

3.BoutayebA,BoutayebS.Theburdenofnoncommunicable dis-easesindevelopingcountries.IntJEquityHealth.2005;4:2. 4.VigitelVigilânciadefatoresderiscoeprotec¸ãoparadoenc¸as

crônicasporinquéritotelefônico:percentualdefumantesno Brasil. Available from: http://www2.inca.gov.br/wps/wcm/ connect/agencianoticias/site/home/noticias/2014/percentual

fumantesbrasilcaimaisumavezvigitel[cited26.01.16]. 5.Warren CW, Jones NR, Eriksen MP, Asma S, Global Tobacco

Surveillance System (GTSS) collaborative group. Patterns of globaltobaccouseinyoungpeopleandimplicationsforchronic diseaseburdeninadults.Lancet.2006;367:749---53.

6.BarretoSM,GiattiL,Oliveira-CamposM,AndreazziMA,Malta DC.Experimentationanduse ofcigaretteandothertobacco products among adolescents in the Brazilian state capitals (PeNSE2012).RevBrasEpidemiol.2014;17:S62---76.

7.BorraciRA,MulassiAH. Tobaccouseduringadolescencemay predictsmokingduringadulthood:simulation-basedresearch. ArchArgentPediatr.2015;113:106---12.

8.SmalleySE,WittlerRR,OliversonRH.Adolescentassessmentof cardiovascularheartdiseasesriskfactorattitudesandhabits.J AdolescHealth.2004;35:374---9.

9.ThomasRE,McLellanJ,PereraR.Effectivenessofschool-based smoking preventioncurricular: systematic review and meta-analysis.BMJOpen.2015;5:e006976.

10.Vigescola --- Vigilância de tabagismo em escolares. Dados e fatosde 12capitaisbrasileiras. Rio de Janeiro:INCA;2004. Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/ vigescolavol1.pdf[cited20.06.15].

11.FigueredoVC,SzkloAS,CostaLC,KuschnirMC,SilvaTL,Bloch KV,etal.ERICA:smokingprevalenceinBrazilianadolescentes. RevSaudePubl.2016;50:12.

12.IBGE-CIDADES. Available from: http://www.cidades.ibge.gov. br/xtras/home.php[cited16.08.16].

13.Californiastudenttobaccosurvey;2011---2012.Availablefrom: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/tobacco/Documents/ CDPH%20CTCP%20Refresh/Research%20and%20Evaluation/ Survey%20Instrument/2011-12%20California%20Student% 20Tobacco%20Survey%20(CSTS)%20Questionnaire–CTCP.pdf [cited16.08.15].

14.GroveA, MartinM,EremencoS,McElroy S,Verjee-LorenzA, Erikson P, et al. Principles of good practice for the trans-lation and cultural adaptation process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force forTranslationandCulturalAdaptation.ValueHeart. 2005;8: 94---104.

16.INCA.Asituac¸ão do tabagismono Brasil:dados dos inquéri-tos do Sistema Internacional de Vigilância, da Organizac¸¯ao MundialdaSaúde,realizadosnoBrasil,ente2002e2009.Rio deJaneiro:InstitutoNacionaldeCâncerJoséAlencarGomesda Silva(INCA);2011.Availablefrom:http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/ bvs/publicacoes/inca/PDFfinalsituacaotabagismo.pdf [cited 20.06.15].

17.CentroBrasileiro de Informac¸o˜essobre DrogasPsicotro´picas. V levantamento nacional sobre o consumo de drogas entre estudantesdoensinofundamentalemédiodaredepu´blicade ensinonas27capitaisbrasileiras;2004.Availablefrom:http:// www.cebrid.epm.br/levantamento brasil2/000-Iniciais.pdf [cited20.06.15].

18.DemirM,KaradenizG,DemirF,KaradenizC,KayaH,Yenibertiz D,etal.Theimpactofanti-smokinglawsonhighschoolstudents inAnkara,Turkey.JBrasPneumol.2015;41:523---9.

19.Brasil,PresidênciadaRepública.LeiFederaln.8.069de13de julhode1990.Dispõe sobreoEstatutodaCrianc¸a edo Ado-lescenteedáoutrasprovidências.Brasília:DiárioOficial(da) RepúblicaFederativadoBrasil;1990.Availablefrom:http:// www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil03/LEIS/L8069.htmSec.1:1.[cited 20.06.15].

20.SchaeferDR,HaasSA,BishopNJ.AdynamicmodelofUS ado-lescents’smokingandfriendshipnetworks.AmJPublicHealth. 2012;102:e12---8.

21.Bricker JB, Peterson AV Jr, Andersen MR, Rajan KB, Leroux BG,SarasonIG.Childhoodfriendswhosmoke: dothey influ-enceadolescentstomakesmokingtransitions?Addict Behav. 2006;31:889---900.

22.ScraggR,LaugesenM,RobinsonE.Parentalsmokingandrelated behaviorsinfluenceadolescenttobaccosmoking:resultsfrom the2001NewZealandnationalsurveyof4thformstudents.N ZMedJ.2003;116:U707.

23.INCA. Número de fumantes no Brasil cai 20,5% em cinco anos. Available from: http://www2.inca.gov.br/wps/wcm/ connect/agencianoticias/site/home/noticias/2014/numero defumantesnobrasilcai20porcentoemcincoanos [cited 20.06.15].

24.MorgensternM,SargentJD, EngelsRC,Scholte RH,FlorekE, HuntK,etal.Smokinginmoviesandadolescentsmoking initi-ation:longitudinalstudyinsixEuropeancountries.AmJPrev Med.2013;44:339---44.

25.WardKD.Thewaterpipe:anemergingglobalepidemicinneed ofaction.TobControl.2015;24:i1---2.

26.LeventhalAM,StrongDR,KirkpatrickMG,Unger JB,Sussman S,RiggsNR,etal.Associationofelectroniccigaretteusewith initiationofcombustibletobaccoproductsmokinginearly ado-lescence.JAmMedAssoc.2015;314:700---7.

27.InstitutoBrasileirodeGeografiaeEstatística.PesquisaNacional deSaúdedo Escolar(PeNSE):2012.Riode Janeiro:Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; 2013. Available from: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/estatistica/populacao/pense/ 2012/[cited30.06.15].

28.LevyD,deAlmeidaLM,SzkloA.TheBrazilSimSmokepolicy sim-ulationmodel:theeffectofstrongtobaccocontrolpolicieson smokingprevalenceandsmoking-attributabledeathsinmiddle incomenation.PLoSMed.2012;9:e1001336.

29.GarciaP.CaminhosdoContrabando.Argentinaonovo corre-dor para o RS. Diario da Fronteira; 2015. Available from: www.facebook.com/diariodafronteira[cited21.06.15]. 30.Thomas RE,McLellan J,Perera R. School-basedprogrammes