www.rbceonline.org.br

Revista

Brasileira

de

CIÊNCIAS

DO

ESPORTE

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Is

drive

for

muscularity

related

to

body

checking

behaviors

in

men

athletes?

Leonardo

de

Sousa

Fortes

a,∗,

Maria

Elisa

Caputo

Ferreira

b,

Pedro

Henrique

Berbert

de

Carvalho

b,

Renato

Miranda

caUniversidadeFederaldePernambuco,CentroAcadêmicodeVitória,NúcleodeEducac¸ãoFísicaeCiênciasdoEsporte,

VitóriadeSantoAntão,PE,Brazil

bUniversidadeFederaldeJuizdeFora,FaculdadedeEducac¸ãoFísicaeDesportos,DepartamentodeFundamentosdaEducac¸ão

Física,JuizdeFora,MG,Brazil

cUniversidadeFederaldeJuizdeFora,FaculdadedeEducac¸ãoFísicaeDesportos,DepartamentodeDesportos,JuizdeFora,

MG,Brazil

Received28August2015;accepted9August2016 Availableonline30September2016

KEYWORDS Bodyimage; Athletes; Psychology; Sports

Abstract Theaimofthisstudywastoanalyzetherelationshipbetweendriveformuscularity andbodycheckingbehaviorsinmenathletes.TwohundredandtwelveBrazilianathletesover 15 yearsofageparticipated.We usedtheDrive forMuscularityScale(DMS) toevaluatethe driveformuscularity.TheMaleBodyCheckingQuestionnairewasusedtoassessbodychecking behaviors.Thefindingsdemonstratedarelationshipbetweenthe‘‘bodyimage-oriented mus-cularity’’subscaleoftheDMSandbodycheckingbehaviors(p=0.001).Theresultsindicated differencesinbodycheckingamong athleteswithhighandlowlevelsofdrivefor muscular-ity.Weconcludedthatdriveformuscularitywasrelated tobody checkingbehaviorsinmen athletes.

©2016Col´egioBrasileirodeCiˆenciasdoEsporte.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisan openaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Imagemcorporal; Atletas;

Psicologia; Esportes

Abuscapelamuscularidadeestárelacionadaaoscomportamentosdechecagem

cor-poralematletasdosexomasculino?

Resumo Oobjetivofoianalisararelac¸ãoentreabuscapelamuscularidadeeos comporta-mentos de checagemcorporal em atletas dosexo masculino. Participaram212atletas com

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:leodesousafortes@hotmail.com(L.deSousaFortes).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbce.2016.08.001

maisde15anos.Usou-seaDriveforMuscularityScale(DMS)eoMaleBodyChecking Ques-tionnaireparaavaliarabuscapelamuscularidadeeoscomportamentosdechecagemcorporal. Encontrou-serelac¸ãoentreasubescala‘‘imagemcorporalorientadaparaamuscularidade’’da DMSeoscomportamentosdechecagemcorporal(p=0,001).Osresultadosrevelaramdiferenc¸as dafrequência de checagemcorporal entreatletas comaltos e baixosníveis de busca pela muscularidade(p=0,001).Concluiu-sequeabuscapelamuscularidadeesteverelacionadaaos comportamentosdechecagemcorporalematletasdosexomasculino.

©2016Col´egioBrasileirodeCiˆenciasdoEsporte.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´e umartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/).

PALABRASCLAVE Imagencorporal; Atletas;

Psicología; Deportes

¿Labúsquedadelamusculaturaserelacionaconelcomportamientodecomprobarel

cuerpoenlosatletasmasculinos?

Resumen Elobjetivofueanalizarla relaciónentrela búsquedademusculaturaylos com-portamientosdecomprobacióndelcuerpoenlosatletasmasculinos.Participaron212atletas mayoresde15a˜nos.SeutilizólaDriveforMuscularityScale(DMS)yelMaleBodyChecking Ques-tionnaireparaevaluarlabúsquedademusculaturayloscomportamientosdecomprobacióndel cuerpo.Seencontróunarelaciónentrela«imagencorporalorientadaalamusculatura»ylos

comportamientosdecomprobacióndelcuerpo(p=0,001).Losresultadosrevelarondiferencias entrelosatletasenlafrecuenciaconquecomprobabanelcuerpoconelevadosybajosniveles debúsquedademusculatura(p=0,001).Seconcluyóquelabúsquedademusculaturaestaba relacionadaconloscomportamientosdecomprobacióndelcuerpoenatletasmasculinos. ©2016Col´egioBrasileirodeCiˆenciasdoEsporte.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Estees unart´ıculoOpenAccessbajolalicenciaCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Body dissatisfaction is related to a preoccupation with weightandphysicalappearance(Rodgersetal.,2011).The populationusuallyshowsdepreciationmainlywithbodyfat (Flamentetal.,2012).Inassumingsuchafindingisdueto concernsoverhealthandesthetics,thismaydrivean indi-vidualtoconsideranathleticlifestyletopursuethe ideal model(Didieetal.,2010;Morgadoetal.,2013).

Recentinvestigationshaveshownthatbody dissatisfac-tioninmalesismoreassociatedwithmuscularity(Flament etal., 2012; Frederick et al., 2007). Drive for muscular-ityreferstothedesiretobemorebeefyandtheadoption ofbehaviorstoachievethedesiredbody(Campanaetal., 2013;McCrearyetal.,2004).Evidenceindicatesmoredesire formuscularityinmalesthanfemales(Flamentetal.,2012). Morespecifically, theselevelsmaybe evenhigherinmen athletes (Frederick et al., 2007; Gapin and Petruzzello, 2011;Steinfeldtetal.,2011).

Results ofa scientific investigation showthat drive for muscularity is closely related to body checking behaviors (Walker et al., 2009). According to Walker et al. (2009), some of behaviorsof male bodychecking are:comparing one’s body with another man’s body, groping or pinching one’smuscles,checkingthesizeofone’smusclesinthe mir-rorandaskingotherstoconfirmtherigidityofmuscles.Body checkingbehaviors maypredispose males to the onsetof muscledysmorphia(Didieetal.,2010),whichisconsidereda

mentalproblemassociatedwithchangesinbodyperception (Azevedoetal.,2012;Walkeretal.,2009).

Muscle dysmorphia is a newly described disorder and is not yet listed in the diagnostic manual of psychiatry; further, the clinical condition has not been well defined. There are few epidemiological studies of the disorder, and most scientific data were obtained from athletes or bodybuilders, thus undermining generalizations about the prevalence of this framework. Researchers have sug-gestedthatmuscle dysmorphiacommonly manifestswhen individuals receive social pressures to achieve a partic-ular body ideal (Didie et al., 2010). Therefore, athletes may be regarded as a risk group for developing muscle dysmorphia.

Inaddition,ifbodyperceptionaftercheckingthemuscles isnotpositive,theathletecanincreasethemagnitudeofthe drivefor muscularity,whichincreasesthesusceptibilityto muscledysmorphia.Researchersstressthatyoungathletes are more susceptible to problems related to body image (Fortesetal.,2014).Soon,thesesameauthorsrecommend statisticallycontrollingforageinstudiesevaluatingathletes fromdifferentagegroup.Itshouldbenoted,though,that although female athletes are more concerned with body image thanmaleathletes (Forteset al.,2014), thereare fewbodyimagestudieswithmaleathletes,whichcanslow theadvancementofknowledgewiththispopulation.Thus, wehighlighttheimportanceofinvestigatingtherelationship betweendriveformuscularityandbodycheckingbehaviors inmenathletes.Thelackofscientificstudiesusingsampled malesisalsohighlighted. Furthermore,surveysconducted inBrazilwithathletesthatcompletedinstruments target-ingmuscularitydidnotprovideinformationonsex.Basedon theseissues,theobjectiveofthisstudywastoanalyzethe relationshipbetweendriveformuscularityandbody check-ingbehaviorsinmenathletes.

Therefore,consideringthenotesofWalkeretal.(2009), a hypothesis was formulated for this research: thereis a relationship between the drive for muscularity and body checkingbehaviorsinmenathletes.

Materials

and

methods

Participants

Thiscross-sectionalstudywasconductedin2013withmale athletes over 15 years of age. According to the Brazil-ian Olympic Committee, in 2013, the population of male athletes (basketball, swimmingand volleyball) aged over 15yearsintheRiodeJaneiroandMinasGeraisStateswas intheorderof3800individuals.Wecarriedoutthesample sizecalculation,considering a95%confidenceinterval,5% samplingerror, 0.8power ofthesample and20%increase forpossiblesampleloss,totaling187athletesneededtobe includedinthesurvey.

Two hundred and twenty-four athletes (basketball [n=69], volleyball [n=63] and swimming [n=92]) par-ticipated and belonged to clubs in the cities of Belo Horizonte/MG, Juiz de Fora/MG, São Lourenc¸o/MG, Leopoldina/MG, Ipatinga/MG, Rio de Janeiro/RJ and Três Rios/RJ, Brazil. The athletes trained in their respective sportanaverageof2hperday,withafrequencyof5times per week. To be included in the study, athletes were requiredto(a)beanathleteforatleast2years,(b) system-aticallytraininasportforat least6hperweek, (c)have playedinacompetitionin2013and(d)havetheavailability toanswerquestionnaires.Itisnoteworthythatnoneofthe evaluatedathletesparticipatedofmentaltrainingprogram overthelastsixmonths.

Three basketball athletes, two volleyball players and seven swimmers were excluded due to incomplete ques-tionnaires. Therefore,the researchstudy included afinal sampleof212athletes[competitivelevel:national(n=163) andinternational(n=49)],asshowninFig.1.

The project was approved by the Ethics and Human Research of the Faculty of Philosophy, Sciences

Sample recruitment

Male athletes (n=224)

Excluded (n=12)

Imcomplete questionnaires (n=9) Imcomplete demographic data (n=3)

Analyzed (n=212)

Figure1 Samplerecruitment.

and Letters of the University of São Paulo (CAE ---05166712.8.0000.5407).Allparticipantsprovidedinformed consent.Weguaranteedanonymitytotheparticipants.

Instruments

Toevaluatedriveformuscularity,weadministeredtheDrive forMuscularityScale(DMS)intheversionvalidatedforthe Brazilianpopulation(Campanaetal.,2013).Itconsistsofa 12-itemquestionnairethatusesaLikertscale(1=neverto 6=always).The higherthescore,thegreatertheconcern anddesiretobemoremuscular.Theinstrumentconsistsof twofactors:bodyimageorientedtomuscularityincludes5 itemsandbehaviororientedmuscularityincludes 7items. The validationstudy of theDMS showedgood psychomet-ric properties for Brazilian men (Campana et al., 2013). The present study identified a Cronbach’s alpha of .80, representingadequate internalconsistency oftheDMS.To conductstatisticalanalyses,weusedthemedianDMSscore (32.00points)oftheparticipantstosplittheathletesinto two groups: athletes with a score <32.00 were included inthe ‘‘lower drive for muscularity’’ group,and athletes withscores≥32.00formedthe‘‘highdriveformuscularity’’

group.

the calculated internal consistency was represented by a Cronbach’salpha=0.94.

Anthropometricdatawerealwayscollectedbythesame evaluator,whowasconsideredexperiencedwiththis eval-uation. Body mass was measured usinga portable digital scale(Tanita)with100gprecision anda maximum capac-ityof200kg.Weusedaportablestadiometer(Welmy)with an accuracy to 0.1cm and a maximum height of 2.20m tomeasurethestatureofathletes.Bodymassindex(BMI) wasobtainedusingthefollowingformula:BMI=bodymass (kg)/height(m2).

Bodyfat wasestimated by skinfoldthickness measure-ment. Skinfold thickness was measured to the nearest 0.1mmontheright sideofthebodywithaLange caliper (CambridgeScientificIndustries,Inc.,Cambridge,MA,USA). Tricipitalandsubscapularskinfoldsweremeasuredfor ath-letes under the age of 18, while the chest skinfold was included for athletes aged 18 years or older. Body fat wasestimated bythe equationsof Slaughteretal.(1988) andJacksonandPollock(1978)for adolescents(<18 years old) and adults (≥18 years old), respectively. For all of

these measurements, the International Society for the Advancementof Kineanthropometry (2013) standards was adopted. In our laboratory, the intra-observer technical errorsofmeasurementforskinfoldthicknessare<5%, mea-suredintriplicate.

Procedures

First, the researchers responsible contacted the coaches in swimming, basketball and volleyball of fifteen clubs in the cities of Juiz de Fora/MG, Belo Horizonte/MG, São Lourenc¸o/MG, Ipatinga/MG, Leopoldina/MG, Rio de Janeiro/RJ and Três Rios/RJ. The procedures and the objectivesofthestudywereproperlyexplained,and autho-rization was sought for the team to participate in the research.However,onlyelevencoachesexpressedinterest thattheirathletesparticipateintheresearch.

Aftertheconsentofthecoach,ameetingwiththe ath-leteswasconductedtoinformpotentialparticipantsabout theethicalproceduresof theresearch.This meeting pro-videdtheICFtotheparentsorguardians(iftheathletewas lessthan18years)thatauthorized,inwriting(bysigningthe term),theparticipationoftheirchildren.

Datacollectionwasconductedintwostages.The test-ingwas always conducted by thesame researcher and in suitablerooms available withinthe participating clubs.A

questionnairecontainingdemographicdata(ageandweekly trainingregimen)wasalsoadministeredtotheathletes.

Thus, the athletes received the same verbal orienta-tionandanydoubtswereclarified.Writtenguidelineswere also contained in the questionnaireson how tocomplete them.Duringtheapplication,therewasnocommunication betweentheathletes,andtherewasnotimelimitfor com-pletion. Theweightandheightof eachathletewerethen measuredindividually.

Dataanalysis

The Kolmogorov---Smirnov test was used to evaluate the distribution of the scores of questionnaires. Given the parametric non-infringement, we used measures of cen-traltendency(mean)anddispersion(standarddeviation)to describethe researchvariables(age, weeklytraining reg-imen, BMI, DMS and MBCQ). We conducted the Stepwise MultipleRegressiontoanalyzetherelationshipbetweenthe of DMSsubscaleswiththetotalscoreof MBCQ.This same test wasusedtoanalyzetherelationship ofbodyfatwith totalscoreofDMSandMBCQ.Inaddition,weused multivari-ateanalysisofcovariance(MANOVA)tocomparethescores oftheMBCQsubscalesaccordingtogroupsestablishedfrom the medianof theDMS. The post hoc Bonferronitest was used toidentify the locationof statistical differences. In addition,we calculatedthe effect sizeusing a Cohen’sd coefficient (Cohen, 1992) to highlight the importance of differences inthe practical pointof view. The effectsize was used with the following threshold values: <0.2: triv-ial;0.2---0.6:small;0.6---1.2:moderate;>1.2:large(Cohen, 1992).Weemphasizeparticularlythatthevariables‘‘age’’ andBMIwerecontrolledinallstatisticaltests.Alldatawere processedusingStatisticalPackageforSocialScience(SPSS) 20.0software,adoptingasignificancelevelof5%.

Results

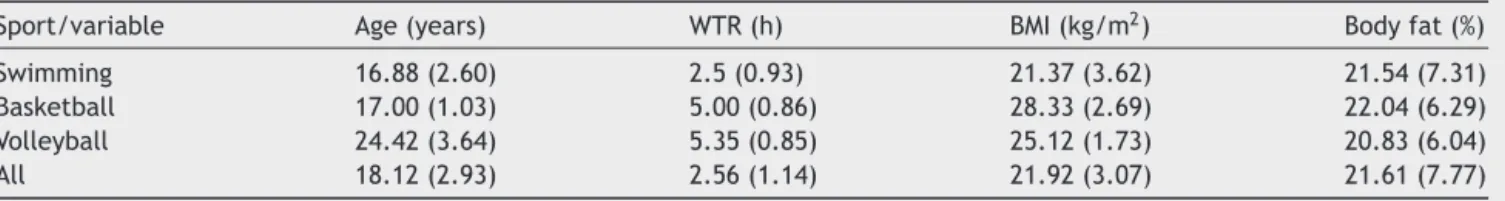

Table1showsthedescriptivedata(meanandstandard devi-ation)forthedemographicvariables(age,weeklytraining regimen,BMIandbodyfat)ofthesample.

Theregression model indicateda relationship between the ‘‘body image oriented for muscularity’’ subscale and bodycheckingbehaviors(F(1,211)=6.12;p=0.001).Similarly,

the‘‘behaviororientedformuscularity’’subscale,inserted in block 2, also demonstrated a relationship with body checkingbehaviors(F(1,211)=9.87;p=0.0001),asshownin

Table2.

Table1 Meanandstandarddeviationofage,weeklytrainingregimen,BMIandbodyfat(%)inthesampleinvestigated(according tosport).

Sport/variable Age(years) WTR(h) BMI(kg/m2) Bodyfat(%)

Swimming 16.88(2.60) 2.5(0.93) 21.37(3.62) 21.54(7.31)

Basketball 17.00(1.03) 5.00(0.86) 28.33(2.69) 22.04(6.29)

Volleyball 24.42(3.64) 5.35(0.85) 25.12(1.73) 20.83(6.04)

All 18.12(2.93) 2.56(1.14) 21.92(3.07) 21.61(7.77)

Source:Authors.

Table2 Stepwise multipleregression using subscales of theDMSasexplanatoryvariablesoftheMBCQscoresinmen athletes.

DMSsubscale Block B R2 R2* pValue

BIOM 1 27.87 0.09 0.08 0.001

BOM 2 22.81 0.15 0.15 0.0001

Source:Authors.

Note: B, Beta;R2*, R2 adjusted; DMS, Drive for Muscularity

Scale;MBCQ, MaleBodyCheckingQuestionnaire; BIOM,body imageorientedtomuscularitysubscale;BOM,behaviororiented muscularitysubscale.

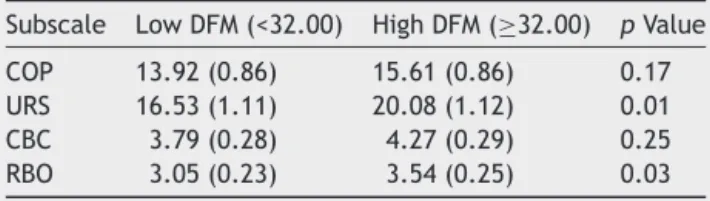

Table3 MeanandstandarderroroftheMBCQ subscales according to the groups established by the DMS in men athletes.

Subscale LowDFM(<32.00) HighDFM(≥32.00) pValue

COP 13.92(0.86) 15.61(0.86) 0.17

URS 16.53(1.11) 20.08(1.12) 0.01

CBC 3.79(0.28) 4.27(0.29) 0.25

RBO 3.05(0.23) 3.54(0.25) 0.03

Note:DMS,DriveforMuscularityScale;DFM,drivefor muscu-larity;COP,comparedtootherpeople;URS,useofreflective surface;CBC,checkby‘‘clamping’’; RBO,reviewofbodyby others.

Theresultsindicatedarelationshipbetweenthebodyfat and DMS score (F(1, 211)=18.76; R2=0.16; p=0.001). Sim-ilarly, thebody fat also demonstrateda relationship with MBCQscore(F((1,211)=31.40;R2=0.23;p=0.0001).

The findingsfromtheMANOVA(Table3) showedhigher scores for the‘‘use ofreflectivesurface’’ (F(7,205)=7.84;

p=0.01;d=0.5)and‘‘reviewofbodybyothers’’subscales (F(7, 205)=4.51; p=0.03; d=0.4) in athletes with scores

greaterthanorequalto34.32ontheDMS.Incontrast,the resultsindicatednodifferencesonthe‘‘comparedwith oth-ers’’(F(7,205)=1.48;p=0.17;d=0.1)or ‘‘checkbymeans

ofclamping’’(F(7,205)=1.14;p=0.26;d=0.1)subscalesdue

totheestablishedclassificationsfortheDMS(lowandhigh DriveforMuscularity).

Discussion

Thisstudyaimedtoanalyzetherelationshipbetweendrive for muscularity andbody checking behaviors in men ath-letes. Scientific reportssuggest that drive for muscularity has a close relationship with body checking behaviors in males (Didie et al., 2010; Walker et al., 2009). From a practical standpoint, menwho show some level of desire tobemoremuscularcancomparetheirbodieswiththose ofothermen,i.e.,lookinginthemirror,checkingthesize ofbodyparts(e.g.,armsandabdomen)andusing supple-mentsand/oranabolicsteroidstoincrease/tonemuscles.It shouldbe notedthatthe reasonsthat generateincreased ofdriveformuscularityandbodycheckingbehaviorsin ath-letes maybe not the same as for the general population. However,nostudywithathletes wasfound,indicating the noveltyofthisresearch.

Thefindingsof Block1oftheregressionmodelshowed that 9% of the variance in body checking behaviors was explainedby the ‘‘bodyimage oriented for muscularity’’ subscale. This result demonstrates that the frequency of checkingthesizeofone’smusclestocomparethephysical selfwithother athletesand looking atreflective surfaces arerelatedtoconcernsaboutbeingmoremuscular. Accord-ingto some authors in the area of body image (Lambrou etal., 2012), concern for the body has a close relation-ship with body checking,confirming the results shown in Block1oftheregressionmodel.Didieetal.(2010)also con-firmedthatthehigherthelevelofconcernwiththemuscles, thegreaterthefrequencyofcheckingbodyparts.Moreover, thesesameauthorsemphasizethatpinchesandpinchingthe musclescangenerateevenmoredepreciationforthebody inmen.Inanexperimentalstudy,Walkeretal.(2012)found thatasinglesessionofbodycheckingdecreasedsatisfaction withthebody.Regardlessofthetemporalprecedence,these authorsnotetherelationshipbetweendriveformuscularity andbodychecking,whichcanbecomeaviciouscycle.

Block2ofthemultipleregressionmodelincreased com-pared with the behaviors of checking when entering the ‘‘behaviororientedfor muscularity’’subscaleof theDMS. The results indicated that 6% of the MBCQ scores were explainedbybehaviorsdirectedatphysicalexerciseandthe useofdietarysupplements.Thus,theathleteswhoengaged inexerciseand/orenjoyedfoodsupplementstobuild mus-clealsoengagedincomparingtheirbodyshapewithother athletes,checkingthetoneoftheirmusclesthroughtapson theirownbodiesandflexingtheirmusclesinmirrors.These findingsareinagreementwiththeinvestigationconducted byQuicketal.(2013).Althoughtheseresearchersdidnot conductstudiesusingyoungmenathletes,theyalsofound thatthebehaviorsofcheckingweightandbodypartswere associatedwithanincreaseinmuscleconduits.

Fairburnetal.(1999)explainedthatindividualsusebody checkingas a formof body verification (evaluation). The informationobtainedisusedindecisionmaking(adoptionof behaviors).Inthecaseofathletes,forexample,after check-ingthebody(e.g.,bodyweight)andverifyingareduction in body weight, the athlete can increase their food con-sumption,useanabolicsteroidsorevenintensifythemuscle workout. Although this process seems straightforward, it shouldbenotedthatthe adoptionofharmfulbehaviorsis generallyimplemented,i.e.,inthepreviousexample(body weight),iftheathletecheckedweightgain(expected objec-tive),hecouldstrengthenhisadoptedstrategiestoensure themaintenance or weight gain. As reported by Fairburn et al. (1999) and Shafran et al. (2007), excessive body checkingleadstodecreasedsatisfactionwiththebodyand theadoptionofdeleterioushealthbehaviors(e.g.,dietary restriction,useofanabolicsteroidsandexcessiveexercise practice).

Inrelationtobodyfat,thefindingsshowedrelationship statisticallysignificant withthe drive for muscularity and bodycheckingbehaviors.Theseresultsindicatethat16%and 23%ofthedriveformuscularityandbodycheckingbehaviors variance,respectively,wereexplainedbybodyfat. Accord-ingtoWalkeretal.(2009),menwithhigherbodyfattendto checkmoreoftenyourbodyparts,whichmayexplainthese findings.

Concerning the comparison of the MBCQ subscales between theathletes with a high and low drive for mus-cularity,ourresultsindicatedahigherfrequencyoftheuse ofreflectivesurfacestoevaluateone’sownbodyinathletes withahighdrive formuscularity. Thesedatademonstrate thatathletesmostconcernedwithmuscleslookinthemirror moreoften thanathleteslessconcernedwithmuscularity. AccordingtoWalkeretal.(2009),thebehaviorofchecking thesize, shapeand definitionof musclein reflective sur-faces is morecommonin subjects withextreme concerns relatedtoachievingacertainmuscularshape.

TheMANOVAshowedthattheathleteswithahighdrive for muscularity most frequently asked others to touch or comment about their muscles, as evidenced through the difference found in the ‘‘review body by others’’ sub-scale.Researchersnotedthatindividualswithconcernand desire tobe more muscular like that friends or acquain-tancesprovidepositivecommentsconcerningtheirmuscular appearance(Walkeretal.,2009),whichexplainstheresults above.

Incontrast,nodifferencesfor the‘‘comparedtoother people’’and‘‘checkbyclamping’’subscalesbetween ath-leteswithahighandlowdriveformuscularitywerefound. Therefore, the frequencies of comparing one’s ownbody with other men and pinching and touching the muscles themselvesweresimilarbetweenathleteswithahighand lowdesiretobemuscular. It maybethat athleteswitha highdrivefor muscularityprefertobetouchedor receive feedback from others about their muscles (results shown forthe ‘‘reviewof bodybyothers’’subscale)ratherthan self-comparing muscular appearance with other athletes. Likewise,bodycheckbypinchingthemusclesandpinching behaviorisnolongerusedbyathleteswithahighdrivefor muscularity.Accordingtothesefindings,theathletes con-cernedwithdevelopingmusclesseemtoadoptbehaviorsof bodycheckingorientedbyextrinsicsuccess.Thismeansthat theseathletesseekapprovalfromotherindividuals depend-ingonthesize,shapeanddefinitionoftheirmusclesbecause theyusemirrors,whichalsoreflecttheirimagesfor other individuals.Moreover,basedonthefindingsforthe‘‘review bodybyothers’’subscale,itseemsthatathletesconcerned withmuscularity like toreceive compliments directed at theirmusclemorphology.

Although the present study shows interesting and new results, it has limitations. One limitation is the use of questionnaires.Fortesetal.(2013)arguethatathletes can-nottruthfullyanswerthequestionnaires.However,Rodgers etal. (2011) emphasize that questionnaires, ifthey have goodpsychometricpropertiesfor thetarget populationof thesurvey,canbeconsideredthegoldstandard.Inaddition, thelowsamplesize(n=212)canalsobeconsidereda limi-tation.However,otherstudieshaveusedsamplesizesthat weresmalleror similarinsize(Fortesetal.,2014;Krentz andWarschburger,2013).Anotherlimitationthatshouldbe

mentionedisthewideagerangeofthesample.But,itnoted thatagewasstatisticallycontrolledinthisstudy,removing thustheireffectonDMSandMBCQscores.Finally,the cross-sectionaldesigndidnotallowcausalinference,i.e.,there isnowaytoevaluatethedirectionoftheseassociations.

Aboveall,thereisalackofstudieswithmenathletes.To addressthisissue,thisinvestigationsoughttocoverasmall portionoftheknowledgegapinthisarea,whichindicates theimportanceofthefindingsfromthisstudy.

Conclusions

The results of thisstudy showed that drive for muscular-itywasrelatedtobodycheckingbehaviorsinmenathletes. Considering this finding, athletes who demonstrate some level of concern about their muscles use body checking behaviorsmore often. However,if theperceptions of the size,shapeanddefinitionofmuscleaftercheckingarenot optimal to the athlete, the feelingof concernwith mus-cularitymaydeteriorate.Longitudinalstudiesthatseekto investigatethecausalrelationshipbetweendrive for mus-cularityandbodycheckinginmenathletesaresuggested.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest

References

AzevedoAP,FerreiraAC,DaSilvaPP,CaminhaIO,FreitasCM.Muscle dysmorphia:aquestforthehypermuscularbody.Motricidade 2012;8(1):53---66.

CampanaANNB,TavaresMCGCF,SwamiV,SilvaD.Anexamination ofthepsychometricpropertiesofBrazilianPortuguese transla-tionsoftheDriveforMuscularityScale,theSwanseaMuscularity AttitudesQuestionnaire,andtheMasculineBodyIdealDistress Scale.PsycholMenMasc2013;14(4):376---88.

Carvalho PHB, Conti MA, Cordás TA, Ferreira MEC. Portuguese (Brazil)translation,semanticequivalenceandinternal consis-tency ofthe Male BodyChecking Questionnaire (MBCQ). Rev PsiquiatrClín2012;39(2):74---5.

CohenJ.Apowerprimer.PsycholBull1992;112(1):155---9. Didie ER, Kuniega-Pietrzak T, Phillips KA. Body image patients

with body dysmorphic disorder: evaluations of and investi-ment in appearance, health-illness, and fitness. Body Image 2010;7(1):66---9.

FairburnCG,ShafranR,CooperZ.Acognitivebehaviouraltheory ofanorexianervosa.BehavResearchTherapy1999;37(1):1---13. FlamentMF,HillEM,BuckholzA,HendersonK,TascaGA. Internaliza-tionofthethinandmuscularbodyidealanddisorderedeatingin adolescence:themediationeffectsofbodyesteem.BodyImage 2012;9(1):68---75.

FortesLS,FerreiraMEC,OliveiraSMF,CyrinoES,AlmeidaSS.A socio-sportsmodelofdisorderedeatingamongBrazilianmaleathletes. Appetite2015;92(1):29---35.

Fortes LS, Kakeshita IS, Gomes AR, Almeida SS, Ferreira MEC. Eating behaviours in youths: a comparison between female and male athletesand non-athletes.Scand JMed Sci Sports 2014;24(1):e62---8.

FrederickAD,Buchana GM,Sadehgi-Azar L, PeplauLA, Haselton MG,BerezovskayaA.Desiringthemuscularideal:men’sbody satisfactionintheUnitedStates,Ukraineand Ghana.Psychol MenMasc2007;8(2):103---17.

Gapin JI, Petruzzello SJ. Athletic identity and disordered eat-ing in obligatory and non-obligatory runners. J Sports Sci 2011;29(10):1001---10.

InternationalSocietyfor theAdvancementofKineanthropometry. Australia. National Libraryof Australia. [Internet homepage] (2013)http://www.isakonline.com[Lastaccessed13.07.13]. JacksonAS,PollockML.Generalizedequationsforpredictingbody

densityofmen.BrJNutr1978;40(4):497---504.

KrentzEM,WarschburgerP.Alongitudinalinvestigationof sports-relatedrisk factorsfor disordered eating inaesthetic sports. ScandJMedSciSports2013;23(2):303---10.

LambrouC,VealeD,WilsonG.Appearanceconcernscomparisons among persons with body dysmorphic disorder and nonclini-calcontrols withand without aesthetic training.Body Image 2012;9(1):86---92.

McCrearyDR,SasseDK,SaucierDM,DorschKD.Measuringthedrive formuscularity:factorialvalidityofthedriveformuscularity scaleinmenandwomen.PsycholMenMasc2004;5(1):49---58. MorgadoJ,MorgadoFFR,TavaresMGCGF,FerreiraMEC.Imagem

cor-poraldemilitares:umestudoderevisão.RevBrasCienEsporte 2013;35(2):521---35.

Quick V,Loth K, MacLehouse R, Linde JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Prevalence of adolescents’ self-weighing behaviors and asso-ciations with weight-related and psychological well-being. J AdolescentHealth2013;52(6):738---44.

RodgersR, CabrolH, PaxtonSJ. Anexploration ofthetripartite influence model of body dissatisfaction and disordered eat-ing amongAustralianandFrench collegewomen.BodyImage 2011;8(1):208---15.

ShafranR,LeeM,PayneE,FairburnCG.Anexperimentalanalysis ofbodychecking.BehavResTherapy2007;45(1):113---21. SilvaC,GomesAR,MartinsL.Psychologicalfactorsrelatedtoeating

disorderedbehaviors:astudywithPortugueseathletes.SpanJ Psychol2011;14(1):323---35.

SlaughterMH,LohmanTG,BoileaR,HoswillCA,StillmanRJ,Yanloan MD.Skinfoldequationsforestimationofbodyfatnessinchildren andyouth.HumBiol1988;60(3):709---23.

Steinfeldt JA, Carter H, Benton E, Steinfeldt MC. Muscular-ity beliefs of female college student-athletes. Sex Roles 2011;64(7):543---54.

WalkerDC,AndersonDA,HilderbrandtT.Bodycheckingbehaviors inmen.BodyImage2009;6(1):164---70.