www.jped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Physical

self-efficacy

is

associated

to

body

mass

index

in

schoolchildren

夽

,

夽夽

Alicia

Carissimi

a,b,∗,

Ana

Adan

c,d,

Lorenzo

Tonetti

e,

Marco

Fabbri

f,

Maria

Paz

Hidalgo

a,b,g,

Rosa

Levandovski

a,b,

Vincenzo

Natale

e,

Monica

Martoni

haUniversidadeFederaldoRioGrandedoSul(UFRGS),HospitaldeClínicasdePortoAlegre(HCPA),LaboratóriodeCronobiologiae

Sono,PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil

bUniversidadeFederaldoRioGrandedoSul(UFRGS),ProgramadePós-Graduac¸ãoemPsiquiatriaeCiênciasdoComportamento,

PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil

cUniversitatdeBarcelona,FacultaddePsicología,DepartamentodePsiquiatríayPsicobiologíaClínica,Barcelona,Spain dUniversitatdeBarcelona,InstitutdeRecercaenCervell,CognicióiConducta(IR3C),Barcelona,Spain

eUniversitàdiBologna,DipartimentodiPsicologia,Bologna,Italy

fSecondaUniversitàdegliStudidiNapoli,DipartimentodiPsicologia,Caserta,Italy

gUniversidadeFederaldoRioGrandedoSul(UFRGS),FaculdadedeMedicina,DepartamentodePsiquiatriaeMedicinaLegal,

PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil

hUniversitàdiBologna,DipartimentodiMedicinaSpecialistica,DiagnosticaeSperimentale,Bologna,Italy

Received9October2015;accepted6April2016 Availableonline3October2016

KEYWORDS

Obesity; Overweight; Childhood;

Physicalself-efficacy; PerceivedPhysical AbilityScalefor Children

Abstract

Objective: The present study aimed to investigate the relationship between physical

self-efficacyandbodymassindexinalargesampleofschoolchildren.

Methods: ThePerceivedPhysicalAbilityScaleforChildrenwasadministeredto1560children

(50.4%boys;8---12years)fromthreedifferentcountries.Weightandheightwerealsorecorded

toobtainthebodymassindex.

Results: Inagreementwiththeliterature,theboysreportedgreaterperceivedphysical

self-efficacythangirls.Moreover,thenumberofboyswhoareobeseisdoublethatofgirls,while

thenumberofboyswhoareunderweightishalfthatfound ingirls.Inthelinearregression

model,theincrease inbodymassindexwas negativelyrelatedtothephysicalself-efficacy

score,differentlyforboysandgirls.Furthermore,ageandnationalityalsowerepredictorsof

lowphysicalself-efficacyonlyforgirls.

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:CarissimiA,AdanA,TonettiL,FabbriM,HidalgoMP,LevandovskiR,etal.Physicalself-efficacyisassociated tobodymassindexinschoolchildren.JPediatr(RioJ).2017;93:64---9.

夽夽

StudyconductedatUniversityofBologna,Bologna,Italy;HospitaldeClínicasdePortoAlegre(HCPA),UniversidadeFederaldoRio GrandedoSul(UFRGS),PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil;andUniversityofBarcelona,Barcelona,Spain.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:alicia.ufrgs@gmail.com(A.Carissimi).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2016.04.011

Conclusion: Theresultsofthisstudyreinforcetheimportanceofpsychologicalaspectof

obe-sity,astheperceivedphysicalself-efficacyandbodymassindexwerenegativelyassociatedin

asampleofschoolchildrenforboysandgirls.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen

accessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/

4.0/).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Obesidade; Sobrepeso; Infância;

Autoeficáciafísica; EscaladeCapacidade FísicaPercebidapara Crianc¸as

Autoeficáciafísicaassociadaaoíndicedemassacorporalemcrianc¸asemidade

escolar

Resumo

Objetivo: Esteestudovisouinvestigararelac¸ãoentreaautoeficáciafísicaeoíndicedemassa

corporalemumagrandeamostradecrianc¸asemidadeescolar.

Métodos: A Escala de Capacidade Física Percebida para Crianc¸as foi administrada a 1560

crianc¸as(50,4%meninos;8-12anos)detrêspaísesdiferentes.Opesoeaalturatambémforam

registradosparaobteroíndicedemassacorporal.

Resultados: Deacordocomaliteratura,osmeninosrelatarammaiorautoeficáciafísica

perce-bida queas meninas. Além disso, o número de meninos obesosé o dobrodo de meninas,

ao passoqueonúmerodemeninosabaixodopesoémetadedodemeninas. Nomodelode

regressão linear,o aumentono índice de massacorporal foi negativamente relacionadoao

escoredeautoeficáciafísica,diferentementeemmeninosemeninas.Alémdisso,aidadeea

nacionalidadetambémforampreditorasdeautoeficáciafísicabaixaapenasparameninas.

Conclusão: Os resultados deste estudo reforc¸am a importância do aspecto psicológico da

obesidade,uma vezqueaautoeficáciafísica percebidaeoíndice demassacorporal foram

negativamenteassociadosemumaamostradecrianc¸asemidadeescolarparameninose

meni-nas.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigo

OpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.

0/).

Introduction

Thehealthbenefitsofregularphysicalactivityforchildren arewellknown.1Togainabetterunderstandingofphysical activitybehavior inchildren, therehas beenan increased focus on determining the relationship between physical activityandpsychosocialcorrelates.2,3Self-efficacy,defined aspeople’s beliefs about their capacity or ability to per-formacertainactionrequiredtoachieveresultsinaspecific situation,4isavariablethatisconsideredtobeassociated withphysicalactivityinadolescents,whichcanbean impor-tantmediatorin providingmore effectiveparticipationin theseactivities.5---7

A recent study on 281 children (116 boys and 165 girls) showed that those who have high physical self-efficacy scores participated in significantly more physical activitycomparedtotheir lowphysical self-efficacyscore counterparts.8 Girls are generally less active and report lowerperceivedphysicalability,aswellashigherperceived body fat and greater body dissatisfaction than boys in a school setting.1,2,6,9,10 Thus, the perceived competence for physical activity seems to be sex-related, due to the fact that boys are more physically active, and per-ceive greater strength and sporting competence than girls.6,11,12

Inadditiontogender,ageisafactorthatmayinfluence physicalself-efficacy,mostevidentlyduringadolescence,6,7 given that physical self-efficacy tends to decrease with increaseofbiologicalage.Anotherfactor,whichcorrelates withself-efficacy, is the body mass index(BMI), an index

ofweight-for-heightthatisusedtoclassifyoverweightand obesity.Changesin perceived physicalabilities9,10,13,14 are influencedbyexcessofweight,relatedtoalowperception of competenceand motivation to performphysical activ-ity,impactingonphysicalactivityparticipationandphysical appearance.15 In fact, higher BMI has been associated to lowerlevelsofself-efficacyfor physicalactivity,including weightstatuspredictedbyphysicalself-efficacyandhealthy eating.16Indeed,olderchildrenandthosewithahigherBMI performlessphysical activity.12 Based onthis evidence,a significant relationship between physical self-efficacyand BMIwasexpectedtobefound.

As demonstratedintheliterature,gender is relatedto BMI, and boys tend to have higher BMI, thus this effect was expected. Therefore, the relationship was explored between physical self-efficacy and BMI in a large sample ofschoolchildren,controllingforconfoundingvariablesthat caninfluencephysicalself-efficacy,suchasage,gender,and nationality.Threecountrieswherethereisaconcernwith theincreased prevalence of overweight andobesity were selected:Italy,17 Spain,18andBrazil.19

Methods

Sample

Spanish (10.54±1.02 years) participants. Students were enrolledbetweenJanuaryandOctober2013onthe condi-tionthatparentssignedtheinformedconsentform.

Measuresandprocedure

Thisstudy presentsdatafromatranscultural projectthat aimstoinvestigatefactors linkedtoenergygainand eat-inghabits,considering theinfluence ofthe rhythmicityof behaviorfromachronobiologicalpointofview.Duringthe schoolyear,studentswereinvitedtoanswerasetof ques-tionnairesaimedatgatheringdataontimingoffoodintake, sleephabits,andphysicalactivity.Duringschoolhours,two membersoftheresearchgroupadministeredquestionnaires inthepresenceoftheteacher.Theteamwenttotheschools at a prearranged time andstudents completed the ques-tionnaires in about 30min. The ethics committee of the universitiesinvolvedintheprojectapprovedthisstudy.

The present study focuses onthe data regarding phys-icalself-efficacy measuredthroughthePerceivedPhysical AbilityScaleforChildren(PPASC)20 inrelationtoage, gen-der,nationality,andBMI.ParticipantscompletedthePPASC, whichconsistsofsixitems:(1)run,rangingfrom1(‘‘Irun veryslowly’’) to4 (‘‘I runvery fast’’);(2) exercise, ran-gingfrom1(‘‘Iamabletodoonlyveryeasyexercises’’)to 4(‘‘Iamabletodoverydifficultexercises’’);(3)muscles, rangingfrom1(‘‘Mymusclesareveryweak’’)to4(‘‘My mus-clesareverystrong’’);(4)move,rangingfrom1(‘‘Imove veryslowly’’)to4 (‘‘Imove veryrapidly’’);(5)sure, ran-gingfrom1(‘‘IfeelveryinsecurewhenImove’’)to4(‘‘I feelverysurewhenImove’’);(6)tired,rangingfrom1(‘‘I feelverytired whenImove’’)to4(‘‘Idon’t feeltiredat allwhenImove’’).Thetotaltestscorecanrangefrom6to 24,andhighscoresindicatethegreatestperceivedphysical self-efficacy.The PPASC assess individuals’ perceptionsof physicalabilitiessuchasstrength,speed,andcoordinative abilities.20 Studieshave foundthatthePPASCis areliable andvalidmeasureofphysicalself-efficacyinchildren.9,10,20 BacktranslationwasperformedinordertousethePPASCin BrazilianPortugueseandSpanish.

Measurements of weight and height were recorded on thesame day that children completed the questionnaire, usingportablescale anda portablestadiometertoobtain theBMI,i.e.,weightinkgdividedbyheightinm2.Children weremeasuredbarefootandwithout outerwearina sepa-rateroom.BMIforagewascalculatedaccordingtogender, andchildrenweredividedintofourcategories,accordingto theinternationalclassificationbyColeetal.:normalweight, underweight,21overweight,andobese.22

Statisticalanalyses

TheKolmogorov---Smirnovtestwasperformedforage,BMI, andself-efficacy;theresultsshowedthatthevariablesdid nothave normal distribution (p-value <0.05). To compare eachoftheconsideredvariables(age,BMI,self-efficacy,and nationality)betweenmalesandfemales,theMann---Whitney Utestforindependentsampleswasused.Tocompareweight categories (underweight, normal weight,overweight, and obese),nationality(Brazilian,Italian,andSpanish),and gen-der, the chi-squared test was employed. To analyze BMI

differencesinrelationtonationality(Brazilian,Italian,and Spanish),separatelybygender,andtocomparetheweight categoriesandthetotalPPASCscore,Kruskal---WallisHtests were performed. The effect size was calculated for the Mann---WhitneyUtestandtheKruskal---WallisHtest.23

Finally,a linearregression wasperformed toevaluate, separately for gender, how the BMI increase, age, and nationalitycouldberelatedtototalperceivedphysical self-efficacy score, using the ‘enter’ method. SPSS (SPSS Inc. 2009. Statistics for Windows, version 18.0, USA) v.18was usedforallstatisticalanalysis.Statisticalsignificancewas setatp<0.05.

Results

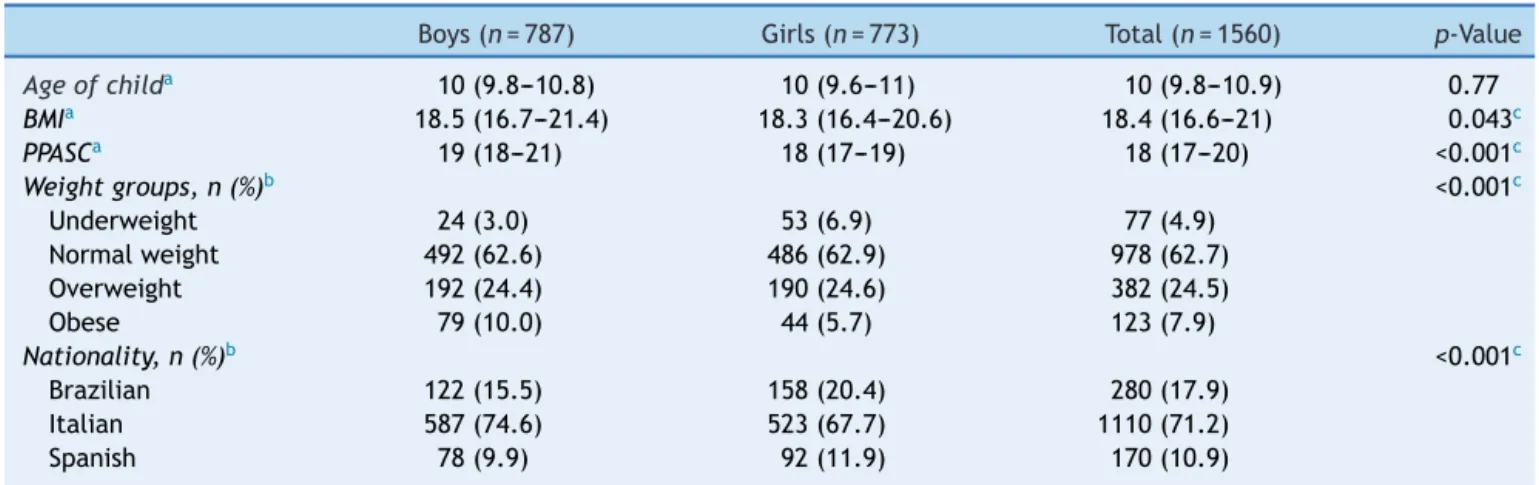

Descriptive data on the sample are displayed in Table 1. ThemedianBMIwassignificantlyhigherforboyscompared withgirls(p=0.043;effectsize=0.059). Thefrequency of thinnessunderweightwashigheringirls(3.4%)thaninboys (1.5%).Ahigherpercentageofboyswereoverweight(12.3%) or obese (5.1%) than girls (12.2%, 2.8%), (p<0.001). The boys(PPASC19;18---21)reportedgreaterperceivedphysical self-efficacythangirls(PPASC18;17---19);(p<0.001;effect size=0.339).

TheBMIfactorshowednodifferencebetweencountries (Brazil, Italy, Spain), when analyzed separately by gen-der in the Kruskal---Wallis H test comparison. The total PPASC score was significantly different for weight cate-gories (p<0.001; effect size=0.003), with a mean rank self-efficacyscoreof724.53forunderweight,826.43for nor-mal weight,702.28 for overweight,and639.22for obese; and for nationality (p<0.001; effect size=0.003), with a meanrankself-efficacyscoreof687.55forBrazilian,812.89 forItalian,and722.11forSpanish.

Results from the linear regression model (Table 2), controlling for the confounders age, BMI, and nationality separatelybygender,demonstratedthatlowerPPASCscore wassignificantly relatedto higherBMI in boys(ˇ=−0.15; p<0.001;adjusted R2=0.044;F=12.98;p<0.001);in girls lower PPASC score was related to higher BMI (ˇ=−0.06; p=0.012), older age (ˇ=−0.29; p=0.001), and nation-ality; it was found that Brazilian girls had the lowest score (ˇ=−0.24; p=0.043; adjusted R2=0.032; F=9.53; p<0.001).

Discussion

Thepresentstudyshowedasignificantrelationshipbetween perceivedphysicalabilityandBMIinasampleof schoolchil-dren.Thisrelationshipemergedassignificantlydifferentfor boysand girls,andfor nationality inthelinear regression analysis.

Table1 Descriptivestatisticsforage,weightstatus,perceivedphysicalself-efficacyscore,andnationality.

Boys(n=787) Girls(n=773) Total(n=1560) p-Value

Ageofchilda 10(9.8---10.8) 10(9.6---11) 10(9.8---10.9) 0.77

BMIa 18.5(16.7---21.4) 18.3(16.4---20.6) 18.4(16.6---21) 0.043c

PPASCa 19(18---21) 18(17---19) 18(17---20) <0.001c

Weightgroups,n(%)b <0.001c

Underweight 24(3.0) 53(6.9) 77(4.9)

Normalweight 492(62.6) 486(62.9) 978(62.7)

Overweight 192(24.4) 190(24.6) 382(24.5)

Obese 79(10.0) 44(5.7) 123(7.9)

Nationality,n(%)b <0.001c

Brazilian 122(15.5) 158(20.4) 280(17.9)

Italian 587(74.6) 523(67.7) 1110(71.2)

Spanish 78(9.9) 92(11.9) 170(10.9)

BMI,bodymassindex;PPASC,PerceivedPhysicalAbilityScaleforChildren. Datashownasmedian(25thto75thpercentile)orn(%).

a Mann---Whitney’sUtest. b Chi-squaredtest.

c Statisticallysignificantdifferences(p<0.05).

byexcessiveweight,whichcontributestoincreasedconcern withself-perceptionsofphysicalabilities.

Of the children evaluatedin this study, approximately 24% of children had excess weight and 8% had obesity (Table1);these statisticsaresimilartothedata foundin the literature,18,26 and these percentages differ between genders.TheBMIresultsdemonstratenodifferenceamong thethreecountriesconsidered;however,itisimportantto highlight thattheprevalenceof overweightandobesityis highinthesecountries.Thesamplewascollectedin south-ern Brazil, a population of Italian and German descent, which is culturally similar to European countries such as ItalyandSpain, suggestingthatthe similaritiesin BMIare morebiologicalthansocio-culturallyderived.Besides, phys-icalself-efficacy may beless affected in a society where havingincreasedBMIisnormal.

In the linearregression model, for boys and girls, the increaseinBMIwasrelatedtoadecreaseinperceived phys-icalself-efficacy score(Table 2). Oneexplanationfor the

increaseinBMIanddecreaseinphysicalself-efficacyscore isthatsomeonewhoisclassifiedasoverweightorobesemay haveaself-perceptionofobesitythatmakeshimorherfeel unfittoperformphysicalactivity.Therefore,achildwhois classifiedasobeseavoidstakingpartinphysicalactivityso asnottobejudgedasbeingunabletoperform,andthus, entersaviciouscircle.Thephysicallyinactivelifestyleisa trigger toweightgain andvice versa.27 Furthermore,age andnationality also were predictors of low physical self-efficacyonlyforgirls.Theresultsunderlinedthedifferences inphysicalself-efficacyforgirlsrelatedtoolderageand dif-ferencesbetweenthecountries,sinceinItaly(meanrank: 408.17) there is a higher score of self-efficacy compared toBrazil(mean rank: 330.78).In Spain, girls(mean rank: 363.24)presentedsimilarPPASCscorestoboys(373.24).

Somelimitationsmayhave animpactonthe generaliz-ability of the present findings. The cross-sectional design of this study excludes statements about causality and directionalityin relation tothe variables of interest. The

Table2 Linearregressionmodeloftotal perceivedphysicalself-efficacyscore,separatelyforgender,andage,bodymass

index,andnationality.

Variables MultivariateB(stderror) Beta Multivariatet p-Value

Boys

AdjustedR2=0.044

Age −0.19(0.11) −0.060 −1.668 0.096

BMI −0.15(0.03) −0.202 −5.768 <0.001a

Nationality −0.10(0.14) −0.024 −0.678 0.498

Girls

AdjustedR2=0.032

Age −0.29(0.09) −0.119 −3.218 0.001b

BMI −0.06(0.03) −0.090 −2.518 0.012b

Nationality −0.24(0.12) −0.074 −2.031 0.043b

perceivedphysicalabilityis onlyoneofmanyfactorsthat influenceobesity.Otherpsychosocialaspectscorrelatingto physicalactivity couldbestudied infutureresearch,such asself-confidence andself-esteem,inordertoclarifythe factors that can promote healthy behaviors. Clearly, age andgendercanbeconsidered,becausetheyinfluencethese variables.Thedifferenceinsamplesizebetweencountries shouldbetakenintoaccount,however, thiscouldbe con-sidered as a strong point of the present work: physical self-efficacyinchildrenwasassessedusingthesame ques-tionnairein Brazil,Italy,andSpain.Moreover,theauthors considered the same international BMI classification cri-terion in each sample and a similar BMI distribution was observed in the three countries. Educational programs28 focused on developing physical skills could consider the associationbetweenphysicalself-efficacyandBMI,29,30and could be a means for improving the self-image of obese children,especiallyduringchildhood.

To conclude,these resultsreinforce the importanceof thepsychologicalaspectofobesity,astheperceived phys-ical self-efficacy and body mass index were negatively associatedinasampleofmaleandfemaleschoolchildren. Furthermore,ageandnationalityalsowerepredictorsoflow physicalself-efficacyonlyforgirls,giventhatlower physi-calself-efficacywasrelatedtobeingolderandBraziliangirls hadthelowestscore.

Funding

This study waspartlysupported by Fondazione delMonte di Bologna e Ravenna (Bologna, Italy), Protocol number 726BIS/2010andFundodeIncentivoàPesquisa(FIPE), Hos-pitaldeClínicasdePortoAlegre(HCPA,Brazil).

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

ThisstudywassupportedbyFundodeIncentivoàPesquisa (FIPE),HospitaldeClínicasdePortoAlegre(HCPA,Brazil), andFondazione delMontediBolognae Ravenna(Bologna, Italy). AC and RML were the recipients of a grant pro-vided by the Brazilian government agency Coordenac¸ão deAperfeic¸oamentodePessoaldeNívelSuperior(CAPES). MPLH was the recipient of a grant provided by Con-selhoNacionaldeDesenvolvimentoCientíficoeTecnológico (CNPq).

References

1.PurslowLR,HillC,SaxtonJ,CorderK,WardleJ.Differences inphysicalactivityandsedentarytimeinrelationtoweightin 8---9yearoldchildren.IntJBehavNutrPhysAct.2008;5:67. 2.FisherA,SaxtonJ,HillC,WebberL,PurslowL,WardleJ.

Psy-chosocialcorrelatesofobjectivelymeasuredphysicalactivity inchildren.EurJPublicHealth.2011;21:145---50.

3.KingAC,ParkinsonKN,AdamsonAJ,MurrayL,BessonH,Reilly JJ,etal.Correlatesofobjectivelymeasuredphysicalactivity

andsedentarybehaviourinEnglishchildren.EurJPublicHealth. 2011;21:424---31.

4.Tsang SK, Hui EK,Law BC. Self-efficacy as a positive youth development construct: a conceptual review. Sci World J. 2012;2012:452327.

5.Kitzman-UlrichH,WilsonDK,VanHornML,LawmanHG. Rela-tionshipofbodymassindexandpsychosocialfactorsonphysical activity in underserved adolescent boys and girls. Health Psychol.2010;29:506---13.

6.SpenceJC,BlanchardCM,ClarkM,PlotnikoffRC,StoreyKE, McCargarL.Theroleofself-efficacyinexplaininggender dif-ferencesinphysicalactivityamongadolescents:a multilevel analysis.JPhysActHealth.2010;7:176---83.

7.deSouzaCA,RechCR,SarabiaTT,A˜nezCR,ReisRS.Self-efficacy andphysicalactivityinadolescentsinCuritiba,ParanáState, Brazil.CadSaudePublica.2013;29:2039---48.

8.SutonD,PfeifferKA,FeltzDL,YeeKE,EisenmannJC,Carlson JJ.Physicalactivity andself-efficacyin normal and over-fat children.AmJHealthBehav.2013;37:635---40.

9.Colella D, Morano M, Robazza C, Bortoli L. Body image, perceivedphysicalability,andmotorperformancein nonover-weight and overweight Italian children. Percept Mot Skills. 2009;108:209---18.

10.Morano M, Colella D, Robazza C, Bortoli L, Capranica L. Physical self-perception and motor performance in normal-weight,overweightandobesechildren.ScandJMedSciSports. 2011;21:465---73.

11.Fairclough SJ, Ridgers ND, Welk G. Correlates of children’s moderateandvigorousphysicalactivityduringweekdaysand weekends.JPhysActHealth.2012;9:129---37.

12.CrespoNC,CorderK,MarshallS,NormanGJ,PatrickK,SallisJF, etal.Anexaminationofmultilevelfactorsthatmayexplain gen-derdifferencesinchildren’sphysicalactivity.JPhysActHealth. 2013;10:982---92.

13.MoranoM,ColellaD,RutiglianoI,FioreP,Pettoello-Mantovani M,CampanozziA.Changesinactualandperceivedphysical abil-itiesinclinicallyobesechildren:a9-monthmulti-component interventionstudy.PLoSONE.2012;7:e50782.

14.FaircloughSJ,BoddyLM,RidgersND,StrattonG.Weightstatus associationswithphysicalactivityintensityandphysical self-perceptionsin10-to11-year-old children.PediatrExercSci. 2012;24:100---12.

15.ZulligKJ,Matthews-EwaldMR,ValoisRF.Weightperceptions, disorderedeatingbehaviors,andemotionalself-efficacyamong highschooladolescents.EatBehav.2016;21:1---6.

16.SteeleMM,DarathaKB, BindlerRC, PowerTG. The relation-shipbetweenself-efficacyforbehaviorsthatpromotehealthy weightandclinicalindicatorsofadiposityinasampleofearly adolescents.HealthEducBehav.2011;38:596---602.

17.LombardoFL,SpinelliA,LazzeriG,LambertiA,MazzarellaG, NardoneP,etal.Severeobesityprevalencein8-to9-year-old Italianchildren:alargepopulation-basedstudy.EurJClinNutr. 2015;69:603---8.

18.AhrensW,PigeotI,PohlabelnH,DeHenauwS,LissnerL,Molnár D,etal.PrevalenceofoverweightandobesityinEuropean chil-drenbelowtheageof10.IntJObes(Lond).2014;38:S99---107. 19.AielloAM,MarquesdeMelloL,SouzaNunesM,SoaresdaSilva A,NunesA.Prevalenceofobesityinchildrenandadolescentsin Brazil:ameta-analysisofcross-sectionalstudies.CurrPediatr Rev.2015;11:36---42.

20.Colella D, Morano M, Bortoli L, Robazza C. A physical self-efficacyscaleforchildren.SocBehavPers.2008;36:841---8. 21.ColeTJ,FlegalKM,NichollsD,JacksonAA.Bodymassindexcut

offstodefinethinnessinchildrenandadolescents:international survey.BMJ.2007;335:194.

23.King BM,Minium EW.Statisticalreasoning inpsychology and education.4thed.NewYork:JohnWiley&Sons;2003. 24.HermanKM, SabistonCM, Tremblay A, Paradis G. Self-rated

health in childrenat risk for obesity: associations of physi-calactivity,sedentarybehaviour,andBMI.JPhysActHealth. 2014;11:543---52.

25.HjorthMF,ChaputJP,RitzC,DalskovSM,AndersenR,AstrupA, etal.Fatnesspredictsdecreasedphysicalactivityandincreased sedentarytime, butnot viceversa: support from a longitu-dinalstudy in8-to 11-year-old children. IntJObes (Lond). 2014;38:959---65.

26.FloresLS,GayaAR,PetersenRD,GayaA.Trendsofunderweight, overweight,andobesityinBrazilianchildrenandadolescents. JPediatr(RioJ).2013;89:456---61.

27.Pietiläinen KH, Kaprio J, Borg P, Plasqui G, Yki-Järvinen H, KujalaUM,etal.Physicalinactivityandobesity:aviciouscircle. Obesity(SilverSpring).2008;16:409---14.

28.Farias Edos S, Gonc¸alves EM, Morcillo AM, Guerra-Júnior G, AmancioOM.Effectsofprogrammedphysicalactivityonbody compositioninpost-pubertalschoolchildren.JPediatr(RioJ). 2015;91:122---9.

29.MartinA,SaundersDH,ShenkinSD,SprouleJ.Lifestyle inter-vention for improving school achievement in overweight or obesechildrenand adolescents.CochraneDatabaseSyst Rev. 2014;3:CD009728.