www.bjorl.org

Brazilian

Journal

of

OTORHINOLARYNGOLOGY

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Profile

and

prevalence

of

hearing

complaints

in

the

elderly

夽

Magda

Aline

Bauer

a,b,

Ângela

Kemel

Zanella

a,

Irênio

Gomes

Filho

c,

Geraldo

de

Carli

c,

Adriane

Ribeiro

Teixeira

c,

Ângelo

José

Gonc

¸alves

Bós

c,∗aPontifíciaUniversidadeCatólicadoRioGrandedoSul(PUC-RS),ProgramadePós-Graduac¸ãoemGerontologiaBiomédica,

PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil

bUniversidadeFederaldoRioGrandedoSul(UFRGS),PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil

cPontifíciaUniversidadeCatólicadoRioGrandedoSul(PUC-RS),PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil

Received26October2015;accepted20June2016 Availableonline31July2016

KEYWORDS

Hearingloss; Epidemiologic studies; Aged

Abstract

Introduction:Hearingisessential forthe processingofacousticinformationandthe under-standingofspeechsignals.Hearinglossmaybeassociatedwithcognitivedecline,depression andreducedfunctionality.

Objective: Toanalyze the prevalenceof hearing complaintsin elderlyindividuals from Rio Grande do Sul anddescribe theprofile ofthe study participants with andwithout hearing complaints.

Methods:7315elderlyindividualsinterviewedintheirhomes,in59citiesinthestateofRio GrandedoSul,Brazil,participatedinthestudy.Inclusioncriteriawereage60yearsorolder andansweringthequestiononauditoryself-perception.Forstatisticalpurposes,thechi-square testandlogisticregressionwereperformedtoassessthecorrelationsbetweenvariables. Results:139elderlyindividualswhodidnotanswerthequestiononauditoryself-perceptionand 9whoself-reportedhearinglosswereexcluded,totaling7167elderlyparticipants.Hearingloss complaintratewas28%(2011)amongtheelderly,showingdifferencesbetweengenders, eth-nicity,income,andsocialparticipation.Themeanageoftheelderlywithouthearingcomplaints was69.44(±6.91)andamongthosewithcomplaint,72.8(±7.75)years.Elderlyindividuals with-outhearingcomplaintshad5.10(±3.78)yearsofformaleducationcomparedto4.48(±3.49) yearsamongthosewhohadcomplaints.Multiplelogisticregressionobservedthatprotective factorsforhearingcomplaintswere:higherlevelofschooling,contributingtothefamilyincome andhavingreceivedhealthcareinthelastsixmonths.Riskfactorsforhearingcomplaintswere: olderage,malegender,experiencingdifficultyinleavinghomeandcarryingoutsocialactivities.

夽 Pleasecitethisarticleas:BauerMA,ZanellaÂK,GomesFilhoI,CarliG,TeixeiraAR,BósÂJ.Profileandprevalenceofhearingcomplaints

intheelderly.BrazJOtorhinolaryngol.2017;83:523---29.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:angelo.bos@pucrs.br(Â.J.Bós).

PeerReviewundertheresponsibilityofAssociac¸ãoBrasileiradeOtorrinolaringologiaeCirurgiaCérvico-Facial.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2016.06.015

Conclusions:AmongtheelderlypopulationofthestateofRioGrandedoSul,theprevalenceof hearingcomplaintsreached28%.Thecomplaintismoreoftenpresentinelderlymenwhodid notparticipateinthegenerationoffamilyincome,whodidnotreceivehealthcare,performed socialandcommunityactivities,hadalowerlevelofschoolingandwereolder.

© 2017 Associac¸˜ao Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia C´ervico-Facial. Published by Elsevier Editora Ltda. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Perdaauditiva; Estudo

epidemiológico; Idoso

Perfileprevalênciadequeixaauditivaemidosos

Resumo

Introduc¸ão:A audic¸ão é essencial para o processamento de eventos acústicos eemissão e compreensãodossinaisdefala.Aperdaauditivapodeestarassociadaaodeclíniocognitivo, depressãoereduc¸ãodafuncionalidade.

Objetivo:AnalisaraprevalênciadequeixaauditivaemidososdoRioGrandedoSuledescrever operfildosparticipantescomesemqueixaauditiva.

Método: Participaramdoestudo7.315idososentrevistadosemsuasresidências,em59cidades gaúchas. Os critérios de inclusão adotados foram ter 60 anos ou mais de idade e terem respondidoàquestãosobreautopercepc¸ãoauditiva.Parafinsestatísticosfoirealizadooteste Qui-quadradoeregressãologísticaparaavaliarascorrelac¸õesentreasvariáveis.

Resultados: Foramexcluídos 139idosos semresposta àautopercepc¸ãoauditiva e novepor autorreferiremsurdez(7.167participantes).Afrequênciadequeixadeperdaauditivafoide 28%(2011)dosidosos,apresentandodiferenc¸aentregêneros,etnia,renda,participac¸ãosocial. Amédiadeidadedosidosossemqueixaauditivafoide69,44(±6,91)ecomqueixa72,8(±7,75) anos.Osidosossemqueixaauditivaapresentaram5,10(±3,78)anosdeestudocomparadoa 4,48(±3,49)anosdoscomqueixa.Aregressãologísticamúltiplaobservouqueforamfatores protetoresparaaqueixaauditivamaiorescolaridade,contribuirnarendafamiliareter rece-bidoatendimentodesaúdenosúltimos seismeses.Fatores derisco paraaqueixaauditiva foramidademaisavanc¸ada,sexomasculino,apresentardificuldadedesairdecasaerealizar atividadessociais.

Conclusões:Napopulac¸ãoidosadoRioGrandedoSulaprevalênciadequeixaauditivaatingiu 28%.Aqueixaestámaispresenteemidososhomens,semparticipac¸ãonarendafamiliar,não receberamatendimentodesaúde,tinhamatividadesocialecomunitária,commenor escolari-dadeemaioridade.

© 2017 Associac¸˜ao Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia C´ervico-Facial. Publicado por Elsevier Editora Ltda. Este ´e um artigo Open Access sob uma licenc¸a CC BY (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

Hearingisessentialfortheprocessingofacoustic informa-tionand for the production and understanding of speech signals.Theconsequencesofhearinglossvaryaccordingto itstype,degreeandageofonset.Inadultsandelderly indi-viduals,one generallyobserves isolation, withdiminished participation in social and family life, sometimes due to thefearof becomingthetarget ofridiculeor contempt.1 Hearinglosscanalsobeassociatedwithcognitivedecline, depressionandreducedfunctionalstatus.2

Becauseof theincrease in thenumbers of theelderly, it is appropriate to understand the factors related to aging and frailty, especially factors related to becoming incapacitated.3Thesecanbecharacterizedbythe interac-tionbetween the individual’s dysfunction(organic and/or structural),restrictionsinsocialparticipationand environ-mentalfactorsthatmayinterferewiththeperformanceof individualactivities.4

Therefore, it is important to evaluate the functional capacity of the elderly in order to correlate it with the practicalaspectsofpersonal careinthemaintenanceand performance of the basic and complex activities of daily living.5Amongthefactorstobeassessedishearing,which isoneofthemajorsensoryalterations6thatcanchangethe dailyhabitsoftheelderly.

Despitetherelevanceofhearinglossintheelderly,few studieshavebeencarriedoutorbeenabletodetermineits incidenceintheBrazilianpopulationorintheirstates.One existingstudycarriedoutinSãoPauloshowedaprevalence of30%ofhearinglossintheelderlypopulation.2This infor-mationisimportantsothattheadequatehearinghealthcare measurescanbetakenandthemagnitudeofthisissuecan beassessedinthepopulation.

Therefore,thisstudyaimstoanalyzetheprevalenceof self-reportedhearingcomplaintsinelderlyindividualsfrom thestate ofRioGrandedoSul,Brazilandtodescribethe epidemiologicalfactorsassociated withelderlyindividuals withandwithouthearingcomplaints.

Methods

Thiswascharacterizedasadescriptiveandcross-sectional study,whichispartofalargersurvey,withfocuson hear-ingfunctionoftheelderly.Thequestionnairewasinspired by the Global Age-friendly Cities: A Guide, of the World HealthOrganization.Theanalyzedanddiscusseddatawere collectedbetweentheyears2010and2011.

In total, 7315 elderly individuals were interviewed in their homes, randomly selected from census sectors of 59 cities in the state of RS. Inclusion criteria were age of 60 years or older and attending the interview. Par-ticipants who could not answer the question onauditory self-perceptionduetocognitiveandcommunication impair-ment were excluded. All participants or their guardians signed the free and informed consent form. The project wasapprovedbytheethicscommitteesoftheinstitutions involvedinthestudy(09/04931and481/09).

Among other issues the elderly were interviewed, abouthearingperception.The variablesgender(male and female), marital status (married, single, widowed, sepa-ratedor divorced,didnotknowhowtoanswer),ethnicity (White, Mixed-Race,Black, other), participationin family income(noincome, mainor sole provider,shared respon-sibility), received care for health problems in the last 6 months(received,didnotreceive),performssocial(does, does not) or community activities (does, does not) and reports difficulties goingout due tocommunication prob-lems (has difficulties, has no difficulties) in addition to hearing aid use (uses, does not use) were treated as categorical variables and expressed as frequencies. Age and educational level (years of formal schooling), these were treated as numerical variables and expressed as mean and standard deviation. The question about hear-ing self-perception had the following response options: ‘‘excellent’’;‘‘good’’;‘‘regular’’;‘‘poor’’and‘‘verypoor’’ ---previouslyestablishedinthequestionnaire.

Forthestatisticalanalysis,auditoryself-perception lev-els of good or excellent were grouped together, as were withoutcomplaintandregular,andpoororverypoor.The chi-square test was usedto test the association between hearingcomplaintsandtheothervariables.Multiplelogistic regressionwasusedtocalculate theoddsratioof hearing losscomplaint beinginfluencedbytheassessed variables. Significancelevelslowerthan5%wereconsidered statisti-callysignificant andbetween5% and10%,asindicativeof significance.10

Results

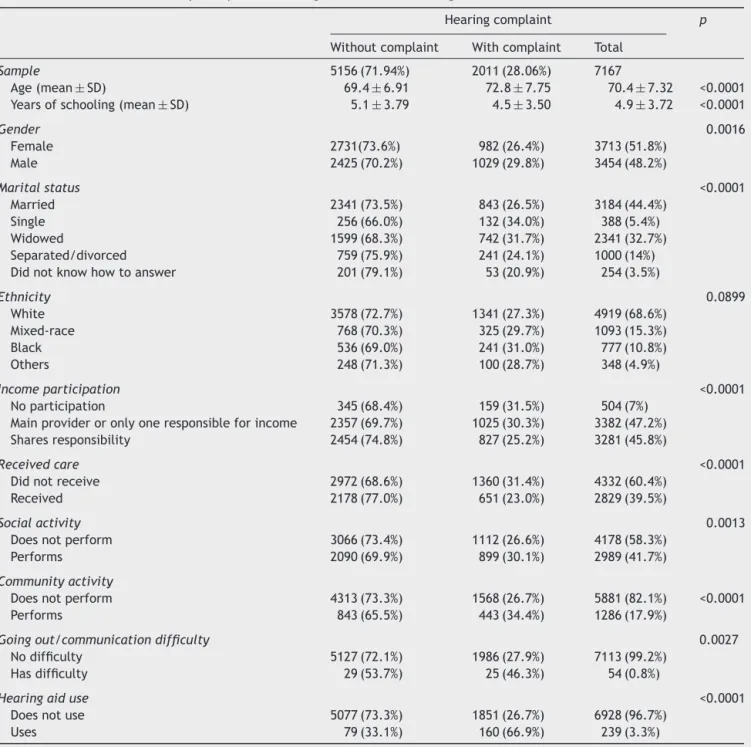

Ofthe7315participants,139wereexcludedbecausethey didnotanswerthequestionaboutauditoryself-perception (cognitiveimpairment)and9becausetheyreportedhearing loss,leaving7167elderlyindividualsinthesample(Table1). Theresultswereexpressedasmeanandstandarddeviation (SD).The mean age of the elderly without hearing com-plaints was69.4(6.91) andin thosewithcomplaint, 72.8 (7.75)years.Theelderlywithouthearingcomplaintshadon average 5.1(3.79) years ofeducation, which wasgreater thanthe4.5(3.49)yearsof educationof thosewith com-plaints. Bothage and educationallevel were significantly different between those with and without hearing com-plaints.

At the logistic regression analysis, both age and educationallevelmaintainedalmostthesamelevelof sig-nificance.Regardingtheyearsofstudy,theresultsshowed thatparticipantswithhearingcomplaintshadfeweryears ofstudy.Eachextrayearofstudywasrelatedto3%lower chanceofhearingcomplaints.Inrelationtoage,eachextra yearwasrelatedtoa6%higherchanceofhearingcomplaints (Table2).

Thehearingcomplaintsweresignificantlymorefrequent in men (p=0.0016). The association between gender and hearing complaints remained significant in the multivari-ateanalysis,after adjustingfor other variables. Although thedifferenceinthefrequenciesfoundinmenandwomen withcomplaints wasonly 3.3% (Table 1), at the multiple analysis men had a 19% higher chance of having hearing complaintsthanwomen,afteradjustingforothervariables (Table2).Regardingthemaritalstatusvariable,itwas sig-nificantforhearinglosscomplaints(p<0.0001).Singleand widowedindividualshadthehighestfrequenciesofhearing complaints,withthelowestbeingobservedinmarriedand separatedindividuals.

To better understand the association between marital statusandhearingcomplaints, asimplelogisticregression was performed, shown in Table 3. Widowers had a 29% higherchance of havinghearingcomplaints, and insingle individuals this percentage was 43%, compared to mar-riedindividuals.Inthemultivariateanalysis,afteradjusting forother factors, thechance of widowed individuals hav-inghearingcomplaintscomparedtomarried onesbecame non-significant,whereas the chance of singles havingthis complaintremainedsimilar(41%)andsignificant,asshown in Table 2. Therefore, the observed difference between marriedandwidowedindividualsinrelationtohearing com-plaintsisdependentonothervariables,includingage.

Asforincome,only7%ofthesamplereportedhavingno participationinfamilyincome(Table1).Theseindividuals showedhigherfrequencyofhearingcomplaints.Thosewho participatedor werethe only or mainproviders of family incomehada significantlylowerchance ofhavinghearing complaints(Table2).

Table1 Characteristicsoftheparticipantsaccordingtothelevelofhearingloss.

Hearingcomplaint p

Withoutcomplaint Withcomplaint Total

Sample 5156(71.94%) 2011(28.06%) 7167

Age(mean±SD) 69.4±6.91 72.8±7.75 70.4±7.32 <0.0001 Yearsofschooling(mean±SD) 5.1±3.79 4.5±3.50 4.9±3.72 <0.0001

Gender 0.0016

Female 2731(73.6%) 982(26.4%) 3713(51.8%)

Male 2425(70.2%) 1029(29.8%) 3454(48.2%)

Maritalstatus <0.0001

Married 2341(73.5%) 843(26.5%) 3184(44.4%)

Single 256(66.0%) 132(34.0%) 388(5.4%)

Widowed 1599(68.3%) 742(31.7%) 2341(32.7%)

Separated/divorced 759(75.9%) 241(24.1%) 1000(14%) Didnotknowhowtoanswer 201(79.1%) 53(20.9%) 254(3.5%)

Ethnicity 0.0899

White 3578(72.7%) 1341(27.3%) 4919(68.6%)

Mixed-race 768(70.3%) 325(29.7%) 1093(15.3%)

Black 536(69.0%) 241(31.0%) 777(10.8%)

Others 248(71.3%) 100(28.7%) 348(4.9%)

Incomeparticipation <0.0001

Noparticipation 345(68.4%) 159(31.5%) 504(7%) Mainprovideroronlyoneresponsibleforincome 2357(69.7%) 1025(30.3%) 3382(47.2%) Sharesresponsibility 2454(74.8%) 827(25.2%) 3281(45.8%)

Receivedcare <0.0001

Didnotreceive 2972(68.6%) 1360(31.4%) 4332(60.4%)

Received 2178(77.0%) 651(23.0%) 2829(39.5%)

Socialactivity 0.0013

Doesnotperform 3066(73.4%) 1112(26.6%) 4178(58.3%)

Performs 2090(69.9%) 899(30.1%) 2989(41.7%)

Communityactivity

Doesnotperform 4313(73.3%) 1568(26.7%) 5881(82.1%) <0.0001

Performs 843(65.5%) 443(34.4%) 1286(17.9%)

Goingout/communicationdifficulty 0.0027

Nodifficulty 5127(72.1%) 1986(27.9%) 7113(99.2%) Hasdifficulty 29(53.7%) 25(46.3%) 54(0.8%)

Hearingaiduse <0.0001

Doesnotuse 5077(73.3%) 1851(26.7%) 6928(96.7%)

Uses 79(33.1%) 160(66.9%) 239(3.3%)

complaints compared to the elderly who did not receive care.Moreover,regardingfollow-up,onlyfourelderly indi-vidualsreportedhavingreceivedaudiologicalfollow-up.

Mostparticipantsdidnotengageinsocialorcommunity activities,butboth activitiesweresignificantlycorrelated with hearing complaints both in the simple analysis and after adjusting for other variables. Those who attended suchactivitiesshowedhigherfrequencyofcomplaintswhen compared to those who did not participate. This can be explainedconsidering thatindividuals whoareexposed to some activities can perceive their worse hearing perfor-mancethanotherswhoarenot exposedtothem,i.e., at homeorinafamiliarenvironmentthatadaptstothem.

People who reported not leaving the house due to communication difficulties comprised only 0.8% of the

sample(Table1),butthisfactorwasaveryimportantone,as almost50%ofthemhadhearingcomplaints.Peoplewhodid notleavethehouseduetocommunicationdifficultieshada 95%higherchanceofhavinghearingcomplaints(Table2).

Of2011 elderly individuals whoreportedhearing com-plaints,only8%usedahearingaid(Table1).Mostofthem, 67%ofthosewhousedahearingaid,hadhearingcomplaints. However,33%didnothavecomplaints.

Discussion

Table2 Resultsofmultiplelogisticregressionforthechanceofhavinghearinglosscomplaints.

Oddsratio Confidenceinterval p

Yearsofschooling 0.9690 0.9538 0.9844 0.0001

Age 1.0602 1.0519 1.0685 <0.0001

Gender(male/female) 1.1939 1.0640 1.3396 0.0026

Maritalstatus(single/married) 1.4076 1.1056 1.7922 0.0055 Maritalstatus(widowed/married) 0.9798 0.8546 1.1232 0.7695 Maritalstatus(separated/married) 0.9690 0.8139 1.1536 0.7235 Incomeparticipation(mainprovider/noparticipation) 0.8903 0.7154 1.1080 0.2978 Incomeparticipation(shares/doesnotshare) 0.7691 0.6175 0.9581 0.0192

Healthcare(yes/no) 0.7388 0.6577 0.8298 <0.0001

Communityactivity(yes/no) 1.4462 1.2434 1.6820 <0.0001 Difficultygoingoutduetocommunicationproblems(yes/no) 1.9518 1.0887 3.4993 0.0247

Socialactivity(yes/no) 1.1593 1.0253 1.3107 0.0183

Table3 Resultofthesimplelogisticregressionofmaritalstatusforthechanceofhavinghearinglosscomplaintsincomparison tothemarriedmaritalstatus.

Oddsratio Confidenceinterval p

Maritalstatus(single/married) 1.4319 1.1442±1.7919 0.0017 Maritalstatus(widowed/married) 1.2886 1.1459±1.4491 <0.0001 Maritalstatus(separated/married) 0.8818 0.7477±1.0399 0.1348

Paulo,which showedaprevalenceof30%.2 Alsosimilarto thatstudy,thepresentonewasbasedonthesubjective com-plaint of hearing difficulty. We believethat the observed frequencywould behigheriftheseelderlyhadundergone hearing assessment throughaudiometry. A previous study performed a comparison between hearingcomplaints and hearinglossandfoundthatthelatterwasmorefrequent,; ofthe50elderlyindividualsinthesample,only12(24%)had aspecificcomplaintofhearingloss,although33(66%)had mild, moderate, severe or profound hearing loss.11 Other studiesusingaudiometryalsofoundhigherfigures.Astudy byMattosandVeras12 carriedoutwithparticipantsfroma universityextensionprojectwiththeelderly,pointedouta prevalenceof41% ofhearinglosscomplaint.Thestudyby Costi etal.13 observed a 45% prevalence of hearing com-plaintsamongparticipantsfromagroupofsenior citizens. Thedifferencescanbeexplainedbythestudy design,the placewhere thestudywascarriedoutandtheindividuals whocomprisedthesample.

Population-based studies on hearing loss are not com-mon,eitherinBrazilorinothercountries.Onlyafewstudies werefoundonthistopic.Oneofthem,aliteraturereview thatpooledsamplesfromEuropeancountrieswith individ-ualsaged60yearsor older,found thatapproximately30% ofmenand20%ofwomenhadsomedegreeofhearingloss at70yearsofage,aswellas55%ofmenand45%ofwomen at age 80.14 This study also found a higherprevalence of hearingcomplaintsamongtheoldestold,withmalesbeing themostoftenaffected.Theincreaseinthecomplaintsof hearingloss duetoagecan beexplainedbythefact that presbycusisisprogressiveandincreasesage,15whichwould lead toa higher number of individuals withself-reported hearingcomplaints.

The influence ofyears ofschoolingcan beobserved in theassesseddata,asthehighertheeducationallevel,the lowerthechanceofhavingahearinglosscomplaint.A sim-ilar result wasobserved in studies in both Brazilian2 and European elderly16 and it might mean that moreyears of schoolingresultingreater care withone’s health andthe adoptionofpreventive measurestopreservehearing. Our data alsosuggest that income can interfere withhearing care, as income was a significantly protective factor for hearingcomplaints.

Whenassessingthequestionaboutreceivinghealthcare andhaving hearing loss, it wasobserved that the elderly whoreceivedsuchcarehadfewercomplaints.Itisbelieved thatsuchoccurrenceisduetothefactthatindividuals with-outhearingcomplaintsseekhealthcare,whencomparedto thosewhodonotstudy,or thosewhoreceivehealth care maybegettingsomecounseling/treatmentforhearingloss prevention.Thiscanalsobeexplainedbythefactthat indi-vidualsmaybereceivinginformationonhearinglossinthe elderlyfromotherprofessionals.Additionally,elderly indi-vidualsmay be experiencing conditionsthat arecommon intheassessedpopulationandmayhavehearingloss asa consequence,suchasdiabetes,hypertension,dyslipidemia, amongothers.

Pandhi et al.17 investigated whether the tendency of elderly individuals in reporting difficulties, delays and decreased satisfaction in access to health care would be related to hearing loss. They found that individuals with hearingimpairmentweremorelikelytoreportdifficultiesin accesstohealthcare;however,hearingwasnotapredictive factorofsatisfactionwithhealthcareaccess.

elderly. Another study showed no significant association betweenphysicalactivityandhearinglosscomplaints.18

Corroboratingthefindingsofourstudy,Chenetal.19 in their researchalso found that hearing loss in the elderly isindependentlyassociatedwithincreasedimpairmentand limitations in several categories of self-reported physical functioning.Incontrast,the studyby Fieldler andPeres20 emphasizesthatthereseemstobeanassociationbetween theincreasedincidence ofhearing lossandthat of physi-calactivitypractice,allowingustoreflectthatindividuals whoperformphysicalactivitymayhavemorecomplaints,as theybecomeannoyedwhentheycannotinteractwiththeir surroundingenvironment.

About the self-reported ethnicity (white, mixed-race, black,orother)andtheassociationwithhearingcomplaints, thedifferencewasnotstatisticallysignificantbetweenthe groupsin ourstudy.However,agreater tendency of com-plaintswasreportedamongblacks,followedbymixed-race andwhiteindividuals.Wemustemphasizethefactthatthe proportionof non-whiteindividuals ismuchsmallerinthe stateofRioGrandedoSulwhencomparedtootherstates of Brazil, with this fact being a reason for not achieving therecommendedlevelofsignificance.Thisfindingdiffers fromthosefound in aNorth-Americanstudy,in whichthe blackethnicity in theelderly wasconsidered significantly protectiveagainsthearingloss.21

Wefoundthatolderindividualswhoself-reporthearing complaints prefer not leaving the house due to commu-nicationdifficulties, but a similarstudy did notshow the same results. It analyzed social isolation and its associa-tionwithhearingloss andfound that agreater degree of hearinglosswasassociatedwithincreasedchancesofsocial isolationonlyinwomenaged60---69years,whereasthis asso-ciationwasnotsignificantinotheragerangesandinmen.22 Individualswhodidnotleavehomeduetocommunication difficultieshada95%higherchanceofhavinghearing com-plaints,accordingtoourfindings.Itissuggestedthathearing losslimitscommunicationandbringssignificantrestrictions totheelderlywhenleavinghome,althoughthiswasnotthe onlycause.

Weobservedthat onlyone-thirdoftheindividuals who used a hearing aid did not mention hearing complaints, thusinferringthatthehearingaidfullymeetstheirhearing needs.Lack ofadjustments or inadequaciescouldexplain thepercentageofindividualswithhearingcomplaintseven whileusingahearingaid.

Whilethenumbersofthisstudy enlightenusaboutthe issuesregardinghearingloss,itisclearthatverylittlehas beendoneabout it.Amongourpopulation,we foundthat onlyfoursubjectsreceivedaudiologyfollow-upand54used hearingaids.Also,wesuggestapopulation-basedstudywith aninstrumentalhearingassessment,sinceitisbelievedthat the number of elderly with complaintsis lower than the numberof thosewhoactually have some degree of hear-ingloss,consideringthathearinglossisprogressive(making iteasierfor theelderly toadapt totheloss),that fewof themperformsocial activities(thus,notbeingexposedto environmentsthatrequiregoodhearing)andthatmostdo notreceivehealthcaremonitoring.

We emphasize the importance of implementing longi-tudinal follow-up studies of elderly patients withhearing loss complaints, so that we can establish different

treatment options,aimed not only at the treatment, but alsoatmoreeffectivepreventioninthisever-growing pop-ulation,especiallyregardingitsclinical,physical,functional andpsychosocialaspects.

Conclusion

Ourstudyclearlyshowsthatthereisaprevalenceof approx-imately 30%ofhearing losscomplaintsamongthe elderly. Thehearingcomplaintisobservedmorefrequentlyinmen withfeweryearsofschooling.Thechanceofhavinghearing complaintsincreaseswithage:foreveryextrayearofage thereisanincreaseof6%inthechanceofhearingloss com-plaint.Thecomplaintwasassociatedwithdecreasedaccess to health care and not leavingthe house due to commu-nicationdifficulties.Ontheotherhand,elderlyindividuals withhigherlevelsofsocialactivityhadahigherfrequency ofhearingcomplaints.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.Francelin MAS, Motti TFG, Morita I. As implicac¸ões soci-aisdadeficiência auditivaadquiridaem adultos. SaúdeSoc. 2010;19:180---92.

2.Cruz MS, Lima MCP, Santos JLF, Duarte YA de O, Lebrão ML, Ramos-Cerqueira AT de A. Deficiência auditiva referida por idososno Municípiode São Paulo, Brasil: prevalência e fatores associados (Estudo SABE, 2006). Cad Saúde Pública. 2012;28:1479---92.

3.Pereira JK, Firmo JOA, Giacomin KC. Maneiras de pensar e de agir de idosos frente às questões relativas à funcionali-dade/incapacidade.CiêncSaúdeColet.2014;19:3375---84. 4.Farias N, Buchalla CM. A classificac¸ão internacional de

fun-cionalidade,incapacidadeesaúdedaorganizac¸ãomundialda saúde: conceitos, usos e perspectivas. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2005;8:187---93.

5.Assis VG, Marta SN, Conti MHS De, Gatti MAN, Simeão SFDAP,VittaADe. Prevalênciaefatoresassociadosà capaci-dadefuncionalde idososnaEstratégiaSaúdeda Famíliaem MontesClaros,MinasGerais,Brasil.RevBrasGeriatrGerontol. 2014;17:153---63.

6.SilvaPLN,MenezesGC,da SC,Rodrigues LCA,OliveiraVGR, FonsecaJR.Hearingscreeningandqualityoflifeinanelderly population.RevEnfermUFPI.2014;3:11---5.

7.MirandaECde,CalaisLL,VieiraEP,CarvalhoLMAde,Borges ACLdeC,Iorio MCM.Dificuldadesebenefícioscom ousode próteseauditiva:percepc¸ãodoidosoesuafamília.RevSocBras Fonoaudiol.2008;13:166---72.

8.FerriteS, Santana VS, Marshall SW. Validity ofself-reported hearinglossinadults:performance ofthreesinglequestions. RevSaúdePública.2011;45:824---30.

9.MariniALS, Halpern R, Aerts D.Sensibilidade especificidade e valor preditivo da queixa auditiva. Rev Saúde Pública. 2005;39:982---4.

10.BósÂJG.EpiInfosemmitérios---ummanualprático.Porto Ale-gre:EDIPUCRS;2012.

12.MattosLC,VerasRP.Aprevalênciadaperdaauditivaemuma populac¸ãodeidososdacidadedoRiodeJaneiro:umestudo seccional.RevBrasOtorrinolaringol.2007;73:654---9.

13.CostiBB,OlchikMR,Gonc¸alvesAK,BeninL,FragaRB,SoaresRS, etal.Perdaauditivaemidosos:relac¸ãoentreautorrelato, diag-nósticoaudiológicoeverificac¸ãodaocorrênciadeutilizac¸ãode aparelhosdeamplificac¸ãosonoraindividual.RevKairós Geron-tol.2014;17:179---92.

14.Roth TN, Hanebuth D, Probst R. Prevalence of age-related hearinglossin Europe:a review. EurArch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;268:1101---7.

15.SousaCS, Castro-Júnior N, LarssonEJ, ChingTH. Estudode fatoresde riscopara apresbiacusia em indivíduosde classe sócio-econômica média. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;75: 530---6.

16.WoodcockK,PoleJD.Educationalattainment,labourforce sta-tusand injury:a comparison ofCanadianswithand without deafnessandhearingloss.IntJRehabilRes.2008;31:297---304.

17.PandhiN,SchumacherJR,BarnettS, SmithMA.Hearing loss andolderadults’perceptionsofaccesstocare.JCommunity Health.2011;36:748---55.

18.GispenFE,ChenDS,GentherDJ,LinFR.Associationofhearing impairmentwithlowerlevelsofphysicalactivityinolderadults. JAmGeriatrSoc.2014;62:1427---33.

19.Chen DS, Genther DJ, Betz J, Lin FR. Association between hearingimpairmentandself-reporteddifficultyinphysical func-tioning.JAmGeriatrSoc.2014;62:850---6.

20.FiedlerMM,PeresKG.Capacidadefuncionalefatoresassociados emidososdoSuldoBrasil:umestudodebasepopulacional.Cad SaúdePública.2008;24:409---15.

21.Lin FR,Thorpe R, Gordon-Salant S, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalenceandriskfactorsamongolderadultsintheUnited States.JGerontolA:BiolSciMedSci.2011;66:582---90. 22.MickP,KawachiI,LinFR.Theassociationbetweenhearingloss