www.jped.com.br

REVIEW

ARTICLE

Autism

in

2016:

the

need

for

answers

夽

Annio

Posar

a,b,∗,

Paola

Visconti

aaIRCCSInstituteofNeurologicalSciencesofBologna,ChildNeurologyandPsychiatryUnit,Bologna,Italy bUniversityofBologna,DepartmentofBiomedicalandNeuromotorSciences,Bologna,Italy

Received23August2016;accepted13September2016 Availableonline9November2016

KEYWORDS

Autismspectrum disorder; Neurobiology; Epidemiology; Environmental factors; Airpollutants; Epigenetics

Abstract

Objective: Autism spectrum disorders are lifelong and often devastating conditions that severelyaffectsocialfunctioningandself-sufficiency.Theetiopathogenesisispresumably multi-factorial,resultingfromaverycomplexinteractionbetweengeneticandenvironmentalfactors. Thedramaticincreaseinautismspectrumdisorderprevalenceobservedduringthelastdecades hasledtoplacingmoreemphasisontheroleofenvironmentalfactorsintheetiopathogenesis. Theobjectiveofthisnarrativebiomedicalreviewwastosummarizeanddiscusstheresultsof themostrecentandrelevantstudiesabouttheenvironmentalfactorshypotheticallyinvolved inautismspectrumdisorderetiopathogenesis.

Sources: AsearchwasperformedinPubMed(UnitedStatesNationalLibraryofMedicine)about theenvironmentalfactorshypotheticallyinvolvedinthenon-syndromicautismspectrum dis-order etiopathogenesis, including: air pollutants, pesticidesand otherendocrine-disrupting chemicals,electromagneticpollution,vaccinations,anddietmodifications.

Summaryofthefindings: Whiletheassociationbetweenair pollutants,pesticidesandother endocrine-disruptingchemicals,andriskfor autismspectrumdisorderisreceivingincreasing confirmation,thehypothesisofarealcausalrelationbetweenthemneedsfurtherdata.The possiblepathogenicmechanismsbywhichenvironmentalfactorscanleadtoautismspectrum disorderingeneticallypredisposedindividualsweresummarized,givingparticularemphasisto theincreasinglyimportantroleofepigenetics.

Conclusions: Future researchshould investigate whetherthereis asignificantdifference in the prevalenceofautismspectrum disorderamongnations withhigh andlowlevelsofthe varioustypesofpollution.Averyimportantgoaloftheresearchconcerningtheinteractions betweengeneticandenvironmentalfactorsinautismspectrumdisorderetiopathogenesisisthe identificationofvulnerablepopulations,alsoinviewofproperprevention.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/ 4.0/).

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:PosarA,ViscontiP.Autismin2016:theneedforanswers.JPediatr(RioJ).2017;93:111---9. ∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:annio.posar@unibo.it(A.Posar).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2016.09.002

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Transtornodo espectroautista; Neurobiologia; Epidemiologia; Fatoresambientais; Poluentes

atmosféricos; Epigenética

Autismoem2016:necessidadederespostas

Resumo

Objetivo: Ostranstornosdoespectroautista(TEAs)sãovitalíciosenormalmentesãodoenc¸as devastadorasqueafetamgravementeofuncionamentosocialeaautossuficiência.A etiopato-geniaé presumivelmente multifatorial,resultante de uma interac¸ãomuito complexa entre fatores genéticos eambientais. Oaumento drásticona prevalênciade TEAs observadonas últimasdécadaslevouàmaiorênfasenopapeldosfatoresambientaisnaetiopatogenia.O obje-tivodestaanálisedanarrativabiomédicafoiresumirediscutirosresultadosdosestudosmais recenteserelevantessobreosfatoresambientaishipoteticamenteenvolvidosnaetiopatogenia dosTEAs.

Fontes: Foi realizada uma pesquisanaBiblioteca Nacional de Medicina dos EstadosUnidos (PubMed)sobreosfatoresambientaishipoteticamenteenvolvidosnaetiopatogeniadosTEAsnão sindrômicos,incluindo:poluentesatmosféricos,pesticidaseoutrosdesreguladoresendócrinos, poluic¸ãoeletromagnética,vacinasealterac¸õesnadieta.

Resumodosachados: Emboraaassociac¸ãoentrepoluentesatmosféricos,pesticidaseoutros desreguladoresendócrinoseoriscodeTEAesteja recebendocadavezmaisconfirmac¸ões,a hipótesedeumarelac¸ãocausalrealentreelesaindaprecisademaisdados.Ospossíveis mecan-ismospatogênicospormeiodosquaisosfatoresambientaispodemcausarTEAemindivíduos geneticamente predispostosforam resumidos,comênfase especial no papel cadavez mais importantedaepigenética.

Conclusões: Futuraspesquisasdeveminvestigarseháumadiferenc¸asignificativana prevalên-ciadeTEAentrenac¸ões comníveis altos ebaixosde váriostiposdepoluic¸ão.Umobjetivo muitoimportantedapesquisaarespeitodasinterac¸õesentrefatoresgenéticoseambientais naetiopatogeniadoTEAéaidentificac¸ãodepopulac¸õesvulneráveis,tambémemvirtudeda prevenc¸ãoadequada.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigo OpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4. 0/).

Introduction

Autismspectrumdisorders(ASDs)arelifelongandoften dev-astating conditionsthat severely affect social functioning andself-sufficiency,having averynegativeimpactonthe livesoftheentirefamilyoftheaffectedindividuals. Accord-ingtothecriteriaoftheDiagnosticandStatisticalManual ofMentalDisorders,5thedition(DSM-5),ASDsaredefined by persisting deficits in social communication and inter-action, as well as by restricted and repetitive behaviors, interests,and activities.1 ASDs presumably have a

multi-factorial etiopathogenesis, resultingfrom a very complex interactionbetween geneticandenvironmentalfactors.2,3

Only in a minority of cases is the presence of a defined medicalconditiondemonstrable.

Epidemiological studies during the last decades have shown a dramatic increase in ASDprevalence, which has reached as much as 1---2% of children in recent years.4

The epidemiological study by Nevison suggests that this increase is mainly real,5 and therefore only in small

part attributable to better knowledge of the problem. Thisphenomenon needsfurtherinvestigation andpossible explanatoryhypothesesintermsofpublichealth.Ofcourse thisprevalenceincreasecannotbeexplainedbasedonlyon geneticfactors,andtheroleofpossibleenvironmental fac-tors should be carefully considered. First, it is necessary tounderstand what has changed in the environment and habitsduring the last few decades. In literature, several

hypotheseshavebeenconsidered.Inthisreview,theauthors carried out a synthesis of the most intriguing hypothe-ses as follows: all the recent (between January 1, 2013 andAugust20,2016)andrelevant(preferablycase---control studies involving humans) literature available on PubMed (UnitedStatesNational LibraryofMedicine)wasselected, usingthefollowingkeywords:‘‘autism’’,‘‘airpollutants’’, ‘‘pollution’’, ‘‘pesticides’’, ‘‘endocrine-disrupting chemi-cals’’,‘‘environmentalfactors’’,‘‘electromagneticfields’’, ‘‘vaccinations’’,‘‘omega-3’’,and‘‘epigenetics’’.

Airpollutants

Over the last years,the etiopathogenic roleof the expo-suretoairpollutants,mainlyheavymetalsandparticulate matter(PM)duringthepre-,peri-,andpostnatalperiod,has beenseriouslyconsideredintheliterature,althoughdefinite conclusionsarelacking.Herefollowsabriefdescriptionof someofthemostimportantrecentpapersinthisregard.

(AD)accordingtotheDiagnosticandStatisticalManualof Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)6

at the age of 3---5 years during the period 1998---2009. They included 7603 children with AD and 10 controls (by definition without documentation of autism) per case matched by sex, year of birth, and minimum gestational age.Theauthorsperformedconditionallogisticregression, adjustingfor:maternalage,birthplace,race/ethnicity,and education;birth type (single,multiple), parity;insurance type(asocioeconomicstatusproxy);andgestationalageat birth.Theycalculateda12---15%relativeincreaseinoddsof autismperinterquartilerange(IQR)increaseforozoneand PM2.5(PMwithanaerodynamicdiameterlessthan2.5m)

when mutually adjusting for both pollutants. Moreover, theycalculateda3---9%relativeincreaseintheoddsofAD perIQRincreaseforLUR-derivedestimatesofexposureto nitricoxideandnitrogendioxide.LUR-derivedassociations were most robust for children born to mothers who had lessthanhighschooleducation.Theauthorsconcludedby suggesting the presence of associations between prenatal exposuretomostlytraffic-relatedairpollutionandautism.7

Volk et al. examined the possible association between air pollution and autism. They performed a population-basedcase---controlstudy inCalifornia(USA)including279 preschoolchildrenwithautism(accordingtoboththeAutism Diagnostic Observation Schedule [ADOS] and the Autism DiagnosticInterview-Revised[ADI-R]) and245normal con-trols,frequencymatchedbysex,age,andbroadgeographic area.Odds ratios for autism were adjusted for children’s sexandethnicity,parents’educationlevel,maternal age, andprenatalsmoking.Childrenwithautism,during gesta-tionand thefirstyear of life,were morelikelytoliveat residenceswiththehighestquartileofexposureto traffic-relatedair pollutioncomparedwithcontrols. Inthe same periods,theexposuretonitrogen dioxide,PM2.5,andPM10

(PMwithan aerodynamic diameterlessthan 10m) were also associated with autism. The authors concluded that during pregnancy and the first year of life, the exposure totraffic-relatedairpollution,nitrogendioxide,PM2.5,and

PM10isassociatedwithautism.8

In Taiwan, Junget al. studied the possible association betweenchildren’slong-termpostnatalexposuretoair pol-lutionandnewlydiagnosedASD.From2000through2010, they performed a prospective population-based cohort studyconsidering49073individualsagedlessthan3years. Withinthiscohort,342childrendevelopedASDaccordingto thecriteriaof theInternational Classificationof Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM).9 Hazard

ratioswere adjustedfor age,anxiety,gender, intellectual disability, preterm birth, and socioeconomic status. The risk of new diagnoses of ASD augmented according to increasing levels of ozone, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide,andsulfurdioxide.Theresultsofthestudysuggest that children’s exposure to these four pollutants in the preceding 1---4 years may increase the risk of developing ASD.Noassociationhasbeen foundbetweenPM10 andthe

riskofnewdiagnosesofASD.10

In theUSA,Roberts etal.studiedthepossible associa-tionbetweenperinatalexposuretoairpollutantsandASD. They estimated associations between levels of hazardous airpollutants atthebirth time/placeandASDinthe chil-dren (325 casesvs. 22101 controls)of participants in the

Nurses’ HealthStudy II, a prospective longitudinal cohort offemalenursesrecruitedin1989.Theauthorsaccounted for possible biasesby adjustingfor family-level and cen-sustract-levelsocioeconomicstatus,maternalageatbirth, andbirth year.Perinatalexposurestothehighestvs. low-estquintileofdieselparticulate,lead,manganese,nickel, andcadmium--- aswell asan overallmeasureof metals ---weresignificantlyassociatedwithASD.Formostpollutants, theassociationwasstrongerformalesthanforfemales.The authorsconcludedthatperinatalexposuretoairpollutants mayincreaseASDrisk,suggestingfurtherstudiesforthe pos-siblesex-specificbiologicalpathwaysassociating perinatal exposuretoairpollutantswithASD.11

Von Ehrenstein et al. evaluated the risks for autism relatedtotheexposuretomonitoredambientairpollutants duringpregnancyinLosAngelesCounty,California.Among the cohort of children born between 1995 and 2006, the authors considered 148722 individuals whose mothers were living in a 5-km buffer radius around air pollution monitoringstationsduringpregnancy.Theauthorsincluded 768 children diagnosed with AD according to DSM-IV-TR criteria6between1998and2009.Therisksforautismwere

heightened per interquartile range increase in average concentrations of several pollutants during pregnancy, including1,3-butadiene,meta/para-xylene,otheraromatic solvents, lead, perchloroethylene, and formaldehyde, adjustingformaternalage,race/ethnicity,nativity, educa-tion,insurancetype,parity,child sex,andbirthyear. The authorsconcludedthatautismrisksinchildrenmayincrease followinginuteroexposuretotraffic-andindustry-related ambientairtoxics.12

Talbottetal.studied thepossible association between prenatalandearlychildhoodexposuretoPM2.5andriskfor

ASD.ASDdiagnosiswasmadeifachildscored≥15 onthe

Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) and had writ-tendocumentation,includingtheADOSorotherdiagnostic toolsresults,ofanASDdiagnosisfromachildpsychologist orpsychiatrist.The authorsperformedapopulation-based case---controlstudy,considering 217ASD children, born in SouthwesternPennsylvania(USA)between2005 and2009, in comparison with 226 controls without ASD, frequency matchedfor age,sex, andrace.Odds ratios(adjusted for maternalage,education,race,andsmoking)werehigh,but notsignificant,forspecificprenatalandpostnatalintervals (pre-pregnancy, pregnancy, and year one), while postna-tal year two was significant. The authors also evaluated theeffectofcumulativepregnancyperiods;starting three monthsbeforepregnancythroughpregnancy,theadjusted oddsratiosweresignificantforpre-pregnancythroughyear two. The authors concludedthat both prenatal and post-natal PM2.5 exposures are associated with increased ASD

risk,suggesting that futurestudies shouldconsider multi-plepollutantmodelsaswellastheelucidationofthePM2.5

involvementintheetiopathogenesisofASD.13

Again in Southwestern Pennsylvania, Talbott et al. performed a population-based case---control study to estimate the possible association between exposure to 30 environmental neurotoxicants and ASD.13 The authors

authorscalculatedoddsratios,adjusted formother’sage, education,race,smokingstatus,child’syearofbirth,and sex.Theyfoundthatlivingduringpregnancyinareaswith higher styrene and chromium levels was associated with increased ASD risk, while borderline effects were found forpolycyclicaromatichydrocarbons(PAHs)andmethylene chloride. However, based on these findings, it is unclear whetherthementionedchemicalsrepresentriskfactorsin themselvesorreflecttheeffectofapollutantmixture.14

ConsideringthatintheUSAchildrenwithASDappearto live in spatial clusters and that the reason for this clus-teringishard todeterminedue toboundless variationsin healthcareaccess and diagnosticpractices, Schelly etal. exploredASDdiffusioninCostaRica,asmallsettingwhere novariations in healthcare access or diagnostic practices are present. In addition, in Costa Rica the potential for exposuretomercuryfromthesourcehypothetically impli-catedin ASD (see coal-fired power plants)is absent,and areaswithhighlevelsofairpollutionarespatially concen-trated.Thestudyincluded118childrenwithASD,diagnosed according to ADOS,assessed in the period of 2010---2013. Theauthorsidentifiedspatialclusterssuggestinga mecha-nismthatdoes notdepend onfactorssuchasinformation aboutASD,healthcareaccess,diagnosticpractices,or envi-ronmental toxicants. The results that emerged from the studydonotsupportthemostlikelyenvironmental cluster-ingcause,whichisairpollution.15

Dickerson et al. performed an ecologic study in five sites located in the USA: in Arizona, Maryland, New Jer-sey,SouthCarolina,andUtah,respectively.Theyexamined theassociationduringthe1990sbetweenprevalenceofASD (diagnosedaccordingtoDSM-IV-TRcriteria6),atthelevelof

censustract,and nearnessof tractcentroids tothe clos-estindustrialfacilities emittingarsenic,lead,ormercury. They analyzed 2489 census tracts with 4486 ASD cases, adjustingfordemographicand socio-economicarea-based characteristics. The authors found thatthe prevalence of ASDwasincreased in censustracts located in the closest 10thpercentilecomparedtothoselocated inthefurthest 50th percentile. The authors concluded that these find-ings suggest an association between residential proximity toindustrialfacilitiesthatemitairpollutantsandincreased ASDprevalence.16

Dickerson et al., again considering the same sample of 4486 children with ASD living in 2489 census tracts, using multi-level negative binomial models, studied the possible association between lead, mercury, and arsenic air concentrations and ASD prevalence. When adjusting for demographic and socio-economic factors, tracts with leadconcentrationsinthehighestquartilehadsignificantly increasedASDprevalencecomparedtotractswith concen-trationsofleadinthelowestquartile.Furthermore,tracts withmercuryconcentrations overthe75thpercentileand arsenicconcentrationsunderthe75thpercentilehada sig-nificantlyincreasedASDprevalencecomparedtotractswith concentrationsofarsenic,lead,andmercuryunderthe75th percentile.Theauthorsconcludedbysuggestingapossible associationbetweenairleadconcentrationsandASD preva-lence, and sustaining that multiple metal exposure may producesynergisticeffectsonthedevelopmentofASD.17

In the USA, Kalkbrenner etal. examined the exposure to PM10 at the birth address in 979 children with ASD,

diagnosedaccordingtoDSM-IV-TR,6bornfrom1994to2000

(645 in North Carolina and 334 in California), compared with 14666 randomly sampled controls born in the same counties and years (12434 in North Carolina and 2232 in California,respectively).Theauthorscalculatedoddsratios of autism for a 10g/m3 increase in PM

10 concentration

within periods of three months fromthe preconceptional periodthroughthe child’sfirstbirthday.Odds ratios were adjusted for year, state, mother’s education and age, race/ethnicity, and neighborhood-level urbanization and median household income. In addition, a nonparametric termforweekofbirthwasincludedtoaccountforseasonal trends. The authors found that PM10 exposure during the

third-trimester,butnotinearlierpregnancy,wasassociated withahigherriskofautism.The authorspointedoutthat theirdatadidnotallowthemtoknowthePMcomposition (PM10 arises fromtraffic,woodsmoke,andpowerplants),

butfurtherresearchinthisfieldisalsoimportantinorder tofacilitatepreventioneffortsagainstthedifferentsources fromwhichthePMcanarise.18

IntheUSA,Razetal.examinedthepossibleassociation between mother’s PM exposure and odds of ASD in her child, performing a nested case---control study of the Nurses’ Health Study II participants.11 They included 245

children with adiagnosis of ASD,confirmed by ADI-R and Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), and 1522 randomly selected children without ASD. During pregnancy the exposuretoPM2.5wasassociatedwithhigheroddsofASD,

with an adjusted (for child sex, year of birth, month of birth, maternal age at birth, paternal age at birth, and censusincome)oddsratioforASDof1.57perIQRincrease inPM2.5,considering onlythewomenwhohadmaintained

the same address before and after pregnancy (160 cases and986controls).TheassociationbetweenPM2.5exposure

andASDwasstrongerinthethirdtrimesterthaninthefirst twotrimestersofpregnancywhenmutuallyadjusted.Little association wasfound between PM10-2.5 (PM withan

aero-dynamic diameter between 10m and 2.5m) and ASD. Theauthorsconcludedthatduringpregnancy,especiallyin thethirdtrimester,ahighermaternal exposuretoPM2.5 is

associatedwithincreasedoddsofachildwithASD.19

Guxens et al. performed a study on four Euro-pean population-based birth/childcohorts. They assessed whetherprenatalexposuretonitrogenoxidesandPM, esti-matedbetween2008and2011,wasassociatedwithautistic traits.Theauthorsincluded8079childrenaged4---10yearsin thestudy.Autistictraitswereassessedusingrespectively: the ASDmoduleofthe Autism---Tics, AttentionDeficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, and Other Comorbidities (A-TAC) inventoryintheSwedishcohort;thePervasive Developmen-tal Problems subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist for Toddlers(CBCL1½---5)intheDutchandintheItaliancohort;

ordertobetterunderstandthedifferentresultscompared tothepreviousstudies.20

Pesticidesandotherendocrine-disrupting chemicals

Endocrinedisrupting chemicals (EDCs)are generally man-made substances that can interfere with the endocrine system, and are present in a large number of home and industrialproducts.ThepossibleassociationbetweenEDCs, inparticular pesticides, andautismhas beendiscussed at length in recent years, so far without reaching definite conclusions.

In the context of the population-based case---control studycalledChildhoodAutismRisksfromGeneticsand Envi-ronment(CHARGE),Shelton etal.explored, inCalifornia, thepossibleassociationbetweenproximityofresidenceto agricultural pesticidesduring gestation andASD or devel-opmentaldelay(DD).For970participants,aged2---5years, commercial pesticideapplication datacollectedusing the CaliforniaPesticide Use Report (from1997 to 2008) were connectedwiththeaddressesduringgestation.Thepounds of active ingredient applied regarding organophophates, organochlorines, pyrethroids,and carbamates (four pesti-cide families selected by the authors) were aggregated within buffer distances of 1.25-km, 1.5-km, and 1.75-km fromtheresidence.The authorsusedmultinomial logistic regression to calculate the exposure odds ratio compar-ing cases affected by ASD (486, diagnosed according to both ADI-R and ADOS), or by DD (168, assessed by the Mullen Scales of Early Learning and the Vineland Adap-tiveBehavioralScale),withnormalcontrols(316)frequency matched to the ASD cases by sex, age, and the regional catchment area.Datawereadjusted for educationof the father, home ownership, birthplace of the mother, child race/ethnicity,maternalprenatalvitaminintake,andyear of birth. During pregnancy, about one-third of the moth-ers lived within 1.5km of an application of agricultural pesticides.Livingnearorganophosphatesatsometime dur-ingpregnancywasassociatedwith60%increasedASDrisk, higher for third-trimester exposure to organophosphates overall,andforsecond-trimesterapplicationsof chlorpyri-fos(anorganophosphateexploredindependently).Children ofmotherslivingnearapplicationsofpyrethroidsduringthe preconceptionperiodorpregnancyatthirdtrimesterwere at higher risk of both ASD and DD. DD risk was higherin thoselivingnearapplicationsofcarbamates,withnospecific vulnerableperiods.Theauthorsconcludedthattheirstudy supportstheassociationbetweenpesticideexposureduring pregnancy,particularlyorganophosphates,and neurodevel-opmentaldisorders,aswellasprovidingnovelfindingsabout theassociationsofpyrethroidsandcarbamateswithASDand DD.21

InCalifornia,Keil etal.examined thepossible associa-tionbetween mother-reported use of imidacloprid,which is a common household pesticide utilized for the treat-mentoffleasandticksforpets,andASD.Participantswere enrolledaspartoftheaforementionedCHARGEstudy.21The

analyticdatasetincluded complete information, collected beforeSeptember2011,for407childrenwithASD(assessed usingADI-RandADOS)and262normalcontrols,frequency

matchedbysex,ageatinterview,andregionofbirth.The authorsusedBayesianlogisticmodelstoevaluatethe associ-ationbetweenimidaclopridandASDaswellastocorrectfor potentialdifferentialexposuremisclassificationbecauseof recallinacase---controlstudyofASD.Atinterview,control caseswereslightlyyoungerthanASDchildren(mean:3years 7monthsand3years10months,respectively).Datawere adjustedfor:child’sgender,birthregionalcenter,andage; mother’seducation,race/ethnicity,andparity;and owner-shipofpetsduringtheprenatalperiod.Theoddsofprenatal exposuretoimidacloprid amongcaseswithASDwereonly slightly higher than among controls. A susceptibility win-dowanalysisshowedhigheroddsratiosforexposuresduring gestation than for exposures during early life, and while consideringonlyconsistentusersofimidacloprid,theodds ratioraisedto2.0.Theauthorsconcludedthatthe associa-tionbetweenexposuretoimidaclopridandASDcouldresult fromexposure misclassification alone, due torecall bias. However, they suggested further investigation about this associationandemphasizedtheneedforvalidationstudies concerningprenatalimidaclopridexposureinpatientswith ASD.22

Unfortunately, both these studies21,22 were based on

(a perfluoroalkyl substance) concentrations were also associatedwithfewerautisticbehaviors.Theselatter asso-ciationswithfewerautisticbehaviorsmaysuggestapossible protective action ofthe involved substances.The authors concluded that some EDCs were associated with greater or fewer childhood autistic behaviors, but the modest size of the sample did not allow them to reach definite conclusions.23

The intriguing hypothesis that EDCs may modify the axes of endogenous hormones, interfering with steroid-dependent neurodevelopment and increasing the ASD risk,23,24stillrequiresexperimentalconfirmation.

Otherenvironmentalfactors

Gao et al. investigated the association between prenatal environmental risk factors and autism in Tianjin (China). They performed a case---control study including 193 chil-dren with autism and 733 typically developed controls matchedbyageandsexfrom2007to2012byusinga ques-tionnaire. The case groupconsisted of childrendiagnosed by a pediatrician according to the criteria of DSM-IV-TR6

and thosewho scored ≥30 on the Childhood Autism

Rat-ingScale (CARS).Statistical analysis wasperformed using QuickUnbiasedEfficientStatisticalTree(QUEST)and logis-ticregressionanalysisinordertocalculatethe oddsratio ofeachriskfactor,adjustedfor socioeconomicfactors.By combiningaclassificationtreeandlogisticregression anal-ysis, the authors found that mother’s depression during pregnancy and neonatal complications (anoxia, jaundice, andaspirationpneumonia)wereassociatedwithincreased risk for child autism, while mother’s air conditioner use and father’s freshwater fish diet before pregnancy were associatedwithreducedriskforchild autism.Theauthors mentioned that air conditioner use might decrease the concentration of air pollutants resulting from lower air PM by filters. Another hypothesis is that a better con-trolled indoor environment could reduce dampness and conditions that favor microbe growth. The fish diet of fathers might help to reduce or prevent paternal obe-sity; alternatively, fish oil might improve the quality of sperm.25

In the present authors’ opinion, the possible involve-mentofelectromagneticpollutioninASDetiopathogenesis isoneof themost intriguinghypotheses,butat thesame time one of the least studied.26 The great increase in

electromagneticpollution,relatedtothehugedeployment ofwirelesstechnologies,seemstooverlapchronologically withtheincrease inautism prevalence detectedover the last decades. A number of studies in the literature have suggestedpossible biologicalandhealtheffects, including carcinogenicity,attributabletoelectromagneticexposure, probably at least in part mediated by damages to the

DNA.27---29 In particular with regard to ASD, the

hypothe-sizedpathogenicmechanismsofelectromagneticpollution include:damages tothe DNA,oxidative stress, intracellu-lar calcium increase, dysfunction of the immune system, and disruption of the blood---brain barrier.28,29 The

obser-vational case---controlstudy performed by Pino-López and Romero-AyusoinSpain,involving70caseswithASDand136 controls (aged16---36 months), suggested the presence of

a correlation between job-related electromagnetic expo-sure of the parents, in particular the father, and ASD in their children.30 However, the study shows some

limita-tions interms ofmethodology,includingthefact thatthe authors useddata froma singlecenter (Ciudad Real)and employedatool(ModifiedChecklistforAutisminToddlers: M-CHAT) not entirely reliable for the diagnosis of ASD. A systematic epidemiological study involving multiple cen-ters located in different geographical areas with diverse electromagneticexposurelevelsisneededtoevaluatethe hypothesis ofan association betweentheelectromagnetic pollutionextentandautismprevalence.26Butunfortunately,

until now these kinds of studies on this topic have been lacking.

The possible role of childhoodvaccinations in the ASD etiopathogenesis hasbeen muchdiscussed over the years and the debate is still ongoing. In their evidence-based meta-analysis,Tayloretal.consideredfivecohortandfive case---controlstudies onthistopic, involving 1256407 and 9920 children,respectively. The cohortdatadid notshow anyrelationsbetween vaccinationandautism orASD,nor between multiple vaccines(MMR),thimerosal,or mercury andautismorASD.Similarly,thecase---controldatadidnot showanincreasedautismorASDriskfollowingexposureto MMR,mercury,orthimerosalwhengroupedbyconditionor bytypeofexposure.Theauthorsconcludedsuggestingthat vaccinationsaswellasthevaccinecomponents(thimerosal ormercury)orMMRarenotassociatedwithanincreasedrisk forautismorASD.31Itishowevertobenotedthat,according

totheobservationofTurvilleandGolden,themeta-analysis of Taylor et al. confirmed previous studies showing that ASD incidence is similar in groups of children who have been differently vaccinated, but it did not compare the ASD incidencein vaccinated and unvaccinated children.32

Therefore, thereis still some uncertainty concerning this matterand,accordingtoSealeyetal.,thistopicshouldbe studiedfurtherandthescientificcommunityshouldstillbe vigilant concerning the possible association between vac-cinesandASD.33However,atpresentforegoingvaccinations

appearstobeanunjustifiedanddangerouschoiceforpublic health.

Van Elst et al. developed an enticing theory accord-ingtowhichtheremaybealinkbetweenpolyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA)andASD.The authorshave pointedout that over the last decades the increase in ASD preva-lenceseemstohavebeen concomitant withmodifications in dietary fatty acid composition, namely the substitu-tionofcholesterolwithomega-6inmanyfoodstuffs,which hascaused aremarkableincrease inthe omega-6/omega-3ratio.The authorshypothesizedthatinparticularduring the life’s earlieststages, an omega-3deficit maylead to alterations of: neurogenesis,synaptogenesis, myelination; neurotransmittersynthesisandturnover;brainconnectivity; expression ofperoxisomeproliferator-activatedreceptors; responses of inflammation; and cognitive functioning and behavior.Alloftheforegoingfactorsappeartoberelated toASD.34 Unfortunately,todate randomizedclinical trials

Early exposure to environmental factors (for example: air pollutants, endocrine-disrupting

chemicals, prenatal maternal infections)

Genetic susceptibility (for example copy-number variations:

CNVs)

Maternal immune activation during

pregnancy

Microbiome modifications

Modifications of epigenetic status and

gene expression

Immune dysregulation and neuroinflammation

Oxidative stress

Mitochondrial dysfunction

Non-syndromic autism spectrum disorder

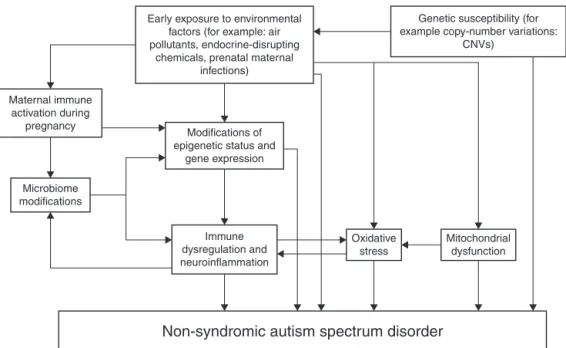

Figure1 Etiopathogenesisofnon-syndromicautismspectrumdisorder.Note:Itsummarizesvariouspossibleinteractionsamong geneticandenvironmentalfactorsinvolvedintheetiopathogenesisofnon-syndromicautismspectrumdisorder.Eacharrow repre-sentsafacilitatingeffect.

Discussion

Todayitiswidelyacceptedthatbothgeneticand environ-mental factors are implicated in the etiopathogenesis of theso-callednon-syndromicASD,whichisnotsecondaryto awell-knowngeneticcondition(suchastuberoussclerosis complexorfragileXsyndrome).Foralongtime,theweight ofthegeneticcomponentwasconsideredclearlyprevalent, butinrecentyears,giventhedramaticincreaseinthe preva-lenceofASD,theroleofenvironmentalfactorshasgained relativelygreaterimportance.Inadditiontotheseobvious epidemiologicalconsiderations,assuggestedbyWongetal., thehypothesisthattheexposuretoenvironmentalfactors mayconsiderablycontributetotheASDdevelopmentis sup-ported by the presence of different subsets of candidate genesineachsubjectwithASDandbythelargephenotypical variabilityoftheseindividuals.36However,thereisstillmuch

todiscover about the complexinteractionbetween these causalfactors. The relatively new concept of epigenetics canbeveryhelpfulinthisregard,atleastina subpopula-tionofcaseswithASD.Epigeneticsrepresentsafundamental generegulationmechanismthatisbasedonchemical modi-ficationsofDNAandhistoneproteins,withoutchangingthe DNAsequence.Ithasbeenproposedthatenvironmental fac-tors,suchasheavymetalsandEDCs,canmodifyepigenetic statusandgeneexpression,causingASD.37,38

However,theetiopathogenicroleofenvironmental fac-tors has still to be considered carefully due to the lack of conclusive data. While the association between, for example, air pollutants and the risk for ASD is receiving increasing confirmation, the hypothesis of a real causal relation betweenthem needsfurtherdata,aswell asthe fact that possible pathogenic mechanisms of the air pol-lutants involved in ASD remain hypothetical. In humans, air pollutant exposure has been shown tofavor oxidative

stress and inflammation,16 which may contribute to ASD

pathogenesis.39 Furthermore, lead, mercury, and arsenic

are known neurotoxicants that can cross the blood-brain barrier andimpairneurodevelopment.16 Epigenetic

mech-anisms may be hypothesized based on the results of the experimentalstudy onanimalscarried outby Hilletal.37

Alsotobe taken intoconsideration is the possibilitythat mixtures of air pollutants, and not single pollutants, are relatedtoASD,duetosynergisticeffects12,17;ofcourse,this

wouldmaketheinterpretationofdataemergingfrom stud-iesaboutpollutantsandASDmuchmoredifficult.According toGuxens et al., the father’sair pollution exposure dur-ingthepreconception periodalsomay havea rolein ASD etiopathogenesis,20 butstudiesaboutthistopicarescanty.

Unfortunately,thecurrentknowledgeinthisfieldisstillat thelevelofassumptionsoronlyalittlefurtherdeveloped.

Ontheotherhand,theimportanceofthegenetic compo-nentintheetiopathogenesisofASDshouldnotbeforgotten, demonstratedbyanimpressiveamountofdatainthe liter-atureovertheyears,andalsoconfirmedtodaybyasimple observation:whiletheprevalenceofthedisorderhasbeen increasing over the last decades, the large disproportion between males and females in favor of the former has beenconfirmed.4IftheetiopathogenesisofASDwasrelated

onlytoenvironmental factors,withwhich bothmalesand femalesareinevitably incontact,thereshouldbeno rea-sonforthispersistingdifferenceinprevalencebetweenthe sexes.

activation) and the affected individual, modifications of themicrobiome (represented by the totality of symbiotic micro-organismsharboredbythehumanbody)thatinturn reciprocallyinteractswiththeimmunefunction,oxidative stress,andmitochondrialdysfunction.37---45Thisschemadoes

notclaimtobeexhaustiveandcertainlywillneedupdates. However,despitethelackofconclusivedata,thepossible impactofenvironmentalpollutantsonpublichealthshould bekeptinmindandthereforetheprecautionaryprinciple, accordingtoSuades-González etal.,should beappliedin ordertoprotectchildrenfrompossiblepathogenicfactors.46

Firstofall,thereareobviousethicalandmoralreasonsto prompta precautionaryapproachtothe pollutants inthe event that this can reduce the occurrence of new cases ofASD. However,evenapart fromthese essential consid-erations,therearealsoreasonsrelatedtothepossibilityof obtaining,withadequateprevention,asavingsofhumanand financialresourcesduetothehighcoststosocietycaused bythemanagementofindividualswithASDoveralifetime.

Conclusions

Despitethegreateffortsperformedduringthelastdecades in medical research, involving considerable human and financialresources,todaymany aspectsofASD etiopatho-genesis are still unknown, while the prevalence of this heterogeneous condition has increased greatly without satisfactory explanations. This led to develop several hypotheses,whichareoftendivergentandstillneed confir-mation.Thankstothehugeamountofdatathathasemerged fromtherecent researchonautism, muchmore informa-tion is now known about the brain functioning of these subjects, but also about the typically-developed individ-uals.However,unfortunately,eventodaythereisnospecific treatment thatcan cure. In2016, it isstill observedthat this disabling disorder is more and more frequent, with-outaknownetiopathogenesisnordecisivetreatments.This situation has indirectlyfavored, in the families involved, theuseoftreatmentsfromcomplementaryandalternative medicine,47aphenomenonthatisnotalwayswithoutrisks

forthepatients.

Futureresearchshouldinvestigatewhetherthereisa sig-nificantdifferenceintheprevalenceofASDamongnations withhigh andlowlevelsofthevarioustypesof pollution. Sofar, thevast majorityofstudies thathavelooked fora correlationbetweenpollutantsandautismhavebeen con-ductedin theUSA. This maybea limiting factor froman epidemiologicalpoint of view, especiallybecausemost of the few studies conducted elsewhere have not confirmed theresultsobtainedinthe USA.Itisunclearwhetherthis is due tomethodological problems or toreal differences between the geographicalareas considered. According to Sheltonetal.,21averyimportantgoaloftheresearch

con-cerningtheinteractionsbetweengeneticsandenvironment istheidentificationofvulnerablepopulations,alsoinviewof properprevention.Finally,anotheraspectthattheauthors considerveryimportantforresearchinthisfieldisthe uni-formityofdiagnosticcriteriaandassessmenttoolsforASD, inordertomaketheresultsofthestudiesperformedacross theworldcomparable.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgments

TheauthorswouldliketothankCeciliaBaronciniforEnglish revision.

References

1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manualofmentaldisorders(DSM-5).5thed.Washington,DC: AmericanPsychiatricAssociation;2013.

2.LyallK, SchmidtRJ, Hertz-PicciottoI.Maternal lifestyleand environmentalriskfactorsforautismspectrumdisorders.IntJ Epidemiol.2014;43:443---64.

3.Bölte S. Is autism curable? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2014;56:927---31.

4.ChristensenDL,BaioJ,VanNaardenBraunK,BilderD,CharlesJ, ConstantinoJN,etal.Prevalenceandcharacteristicsofautism spectrumdisorderamongchildrenaged8years---Autismand DevelopmentalDisabilitiesMonitoringNetwork,11Sites,United States,2012.MMWRSurveillSumm.2016;65:1---23.

5.NevisonCD.AcomparisonoftemporaltrendsinUnitedStates autismprevalencetotrendsinsuspectedenvironmental fac-tors.EnvironHealth.2014;13:73.

6.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manualofmentaldisorders,textrevision(DSM-IV-TR).4thed. Washington,DC:AmericanPsychiatricAssociation;2000. 7.BecerraTA,WilhelmM,OlsenJ,CockburnM,RitzB.Ambientair

pollutionandautisminLosAngelesCounty,California.Environ HealthPerspect.2013;121:380---6.

8.Volk HE,Lurmann F,Penfold B, Hertz-Picciotto I,McConnell R.Traffic-relatedairpollution,particulatematter,andautism. JAMAPsychiatry.2013;70:71---7.

9.Practice Management Information Corporation. International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM).LosAngeles,CA:PracticeManagementInformation Corporation;1999.

10.JungCR,LinYT,HwangBF.Airpollutionandnewlydiagnostic autismspectrumdisorders:apopulation-basedcohortstudyin Taiwan.PLOSONE.2013;8:e75510.

11.RobertsAL,LyallK,HartJE,LadenF,JustAC,BobbJF,etal. Perinatalairpollutantexposuresandautismspectrumdisorder inthechildrenofNurses’HealthStudyIIparticipants.Environ HealthPerspect.2013;121:978---84.

12.von Ehrenstein OS, Aralis H, Cockburn M, Ritz B. In utero exposuretotoxicairpollutantsandriskofchildhoodautism. Epidemiology.2014;25:851---8.

13.TalbottEO,ArenaVC,RagerJR,CloughertyJE,MichanowiczDR, SharmaRK,etal.Fineparticulatematterandtheriskofautism spectrumdisorder.EnvironRes.2015;140:414---20.

14.TalbottEO,MarshallLP,RagerJR,ArenaVC,SharmaRK,Stacy SL. Airtoxics and the riskof autismspectrumdisorder: the resultsofapopulationbasedcase---controlstudyin southwest-ernPennsylvania.EnvironHealth.2015;14:80.

15.SchellyD,JiménezGonzálezP,SolísPJ.Thediffusionofautism spectrumdisorderinCostaRica:evidenceofinformationspread orenvironmentaleffects?HealthPlace.2015;35:119---27. 16.DickersonAS,RahbarMH,HanI,BakianAV,BilderDA,Harrington

17.Dickerson AS, Rahbar MH, Bakian AV, Bilder DA, Harrington RA,PettygroveS,etal.Autismspectrumdisorderprevalence andassociationswithairconcentrationsoflead,mercury,and arsenic.EnvironMonitAssess.2016;188:407.

18.Kalkbrenner AE, Windham GC, Serre ML, Akita Y, Wang X, HoffmanK,et al.Particulatematterexposure,prenataland postnatalwindowsofsusceptibility,andautismspectrum disor-ders.Epidemiology.2015;26:30---42.

19.RazR,Roberts AL,Lyall K,Hart JE,JustAC,LadenF,etal. Autismspectrumdisorderandparticulatematterairpollution before,during, and after pregnancy: a nested case---control analysis within the Nurses’ Health Study II Cohort. Environ HealthPerspect.2015;123:264---70.

20.Guxens M, Ghassabian A, Gong T, Garcia-Esteban R, Porta D, Giorgis-Allemand L, et al. Air pollution exposure dur-ingpregnancyand childhood autistictraits infour European population-basedcohortstudies:theESCAPEProject.Environ HealthPerspect.2016;124:133---40.

21.SheltonJF,GeraghtyEM,TancrediDJ,DelwicheLD,SchmidtRJ, RitzB,etal.Neurodevelopmentaldisordersandprenatal resi-dentialproximitytoagriculturalpesticides:theCHARGEstudy. EnvironHealthPerspect.2014;122:1103---9.

22.KeilAP,DanielsJL, Hertz-PicciottoI.Autismspectrum disor-der,fleaand tickmedication, and adjustmentsfor exposure misclassification:the CHARGE (CHildhood Autism Risks from GeneticsandEnvironment)case---controlstudy.EnvironHealth. 2014;13:3.

23.BraunJM,KalkbrennerAE,JustAC,YoltonK,CalafatAM,Sjödin A,etal.Gestationalexposuretoendocrine-disrupting chemi-calsandreciprocalsocial,repetitive,andstereotypicbehaviors in4-and5-year-oldchildren:theHOMEstudy.EnvironHealth Perspect.2014;122:513---20.

24.BraunJM.Endocrinedisruptingcompounds,gonadalhormones, andautism.DevMedChildNeurol.2012;54:1068.

25.Gao L, Xi QQ, Wu J, Han Y, Dai W, Su YY, et al. Associa-tionbetweenprenatalenvironmentalfactorsandchildautism: a case control study in Tianjin, China. Biomed Environ Sci. 2015;28:642---50.

26.PosarA,ViscontiP.Towhat extentdoenvironmentalfactors contributetotheoccurrenceofautismspectrumdisorders?J PediatrNeurosci.2014;9:297---8.

27.BaanR,GrosseY,Lauby-SecretanB,ElGhissassiF,BouvardV, Benbrahim-TallaaL, et al. Carcinogenicityof radiofrequency electromagneticfields.LancetOncol.2011;12:624---6. 28.Herbert MR, Sage C. Autism and EMF? Plausibility of a

pathophysiological link --- part I. Pathophysiology. 2013;20: 191---209.

29.Herbert MR, Sage C. Autism and EMF? Plausibility of a pathophysiological link --- part II. Pathophysiology. 2013;20: 211---34.

30.Pino-LópezM,Romero-AyusoDM.Parentaloccupational expo-suresandautismspectrumdisorderinchildren.RevEspSalud Publica.2013;87:73---85.

31.TaylorLE,SwerdfegerAL,EslickGD.Vaccinesarenotassociated withautism:anevidence-basedmeta-analysisofcase---control andcohortstudies.Vaccine.2014;32:3623---9.

32.Turville C, Golden I. Autism and vaccination: the value of the evidence base of a recent meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2015;33:5494---6.

33.Sealey LA, Hughes BW, Sriskanda AN, Guest JR, Gibson AD, Johnson-Williams L, et al. Environmental factors in the development ofautism spectrum disorders.Environ Int. 2016;88:288---98.

34.vanElstK,BruiningH,BirtoliB,TerreauxC,BuitelaarJK,Kas MJ.Foodfor thought:dietarychangesinessentialfattyacid ratiosandtheincreaseinautismspectrumdisorders.Neurosci BiobehavRev.2014;45:369---78.

35.PosarA,ViscontiP.Complementaryandalternativemedicinein autism:thequestionofomega-3.PediatrAnn.2016;45:e103---7. 36.Wong CT, Wais J, Crawford DA. Prenatal exposure to com-monenvironmental factors affectsbrainlipidsand increases riskofdevelopingautismspectrumdisorders.EurJNeurosci. 2015;42:2742---60.

37.Hill DS, Cabrera R, Wallis Schultz D, Zhu H, Lu W, Finnell RH,et al.Autism-likebehavior andepigenetic changes asso-ciatedwithautismas consequencesof inuteroexposure to environmental pollutants in a mouse model. Behav Neurol. 2015;2015:426263.

38.KubotaT,MochizukiK.Epigeneticeffectofenvironmental fac-tors on autismspectrum disorders. Int J Environ ResPublic Health.2016;13:E504.

39.GhezzoA,ViscontiP,AbruzzoPM,BolottaA,FerreriC,GobbiG, etal.Oxidativestressanderythrocytemembranealterationsin childrenwithautism:correlationwithclinicalfeatures.PLOS ONE.2013;8:e66418.

40.Block ML, Calderón-Garcidue˜nas L. Air pollution: mecha-nismsofneuroinflammationandCNSdisease.TrendsNeurosci. 2009;32:506---16.

41.Rossignol DA,Frye RE.Areviewof researchtrendsin physi-ological abnormalitiesinautismspectrumdisorders:immune dysregulation, inflammation, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunctionandenvironmentaltoxicantexposures.Mol Psychi-atry.2012;17:389---401.

42.GraysonDR,Guidotti A. Mergingdatafrom geneticand epi-genetic approaches to better understand autistic spectrum disorder.Epigenomics.2016;8:85---104.

43.Nardone S, Elliott E. The interaction between the immune systemandepigeneticsintheetiologyofautismspectrum dis-orders.FrontNeurosci.2016;10:329.

44.MoosWH, FallerDV,HarppDN, KanaraI,Pernokas J,Powers WR,etal.Microbiotaandneurologicaldisorders:agutfeeling. BioresOpenAccess.2016;5:137---45.

45.WongS,Giulivi C.Autism,mitochondriaand polybrominated diphenyl ether exposure. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2016;15:614---23.

46.Suades-GonzálezE,GasconM,GuxensM,SunyerJ.Air pollu-tionandneuropsychologicaldevelopment:areviewofthelatest evidence.Endocrinology.2015;156:3473---82.