www.jped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Do

infants

with

cow’s

milk

protein

allergy

have

inadequate

levels

of

vitamin

D?

夽

Cristiane

M.

Silva

a,∗,

Silvia

A.

da

Silva

a,

Margarida

M.

de

C.

Antunes

b,

Gisélia

Alves

Pontes

da

Silva

c,

Emanuel

Sávio

Cavalcanti

Sarinho

c,d,

Katia

G.

Brandt

baUniversidadeFederaldePernambuco(UFPE),ProgramadePósGraduac¸ãoemSaúdedaCrianc¸aedoAdolescente,Recife,PE,

Brazil

bUniversidadeFederaldePernambuco(UFPE),DepartamentoMaterno-Infantil,Servic¸odeGastroenterologiaPediátrica

HC-UFPE,Recife,PE,Brazil

cUniversidadeFederaldePernambuco(UFPE),DepartamentoMaterno-Infantil,ProgramadePósGraduac¸ãoemSaúdedaCrianc¸a

edoAdolescente,Recife,PE,Brazil

dUniversidadeFederaldePernambuco(UFPE),DepartamentoMaterno-Infantil,Servic¸odeAlergologiaeImunologiaHC-UFPE,

Recife,PE,Brazil

Received16August2016;accepted6January2017 Availableonline17June2017

KEYWORDS

Milkallergy; Infant; VitaminD; Breastfeeding; Sunlight

Abstract

Objective: Toverifywhetherinfantswithcow’smilkproteinallergyhaveinadequatevitamin Dlevels.

Methods: Thiscross-sectionalstudyincluded120childrenaged2yearsoryounger,onegroup withcow’smilkproteinallergyandacontrolgroup.Thechildrenwererecruitedatthepediatric gastroenterology,allergology,andpediatricoutpatient clinicsofauniversityhospitalinthe NortheastofBrazil.Aquestionnairewasadministeredtothecaregiverandbloodsampleswere collectedforvitaminDquantification.VitaminDlevels<30ng/mLwereconsideredinadequate. VitaminDlevelwasexpressedasmeanandstandarddeviation,andthefrequencyofthedegrees ofsufficiencyandothervariables,asproportions.

Results: Infants with cow’s milk protein allergy had lower mean vitamin D levels (30.93 vs.35.29ng/mL;p=0.041)andhigherdeficiencyfrequency(20.3%vs.8.2;p=0.049)thanthe healthycontrols.Exclusivelyorpredominantlybreastfedinfantswithcow’smilkproteinallergy hadhigherfrequencyofinadequatevitaminDlevels(p=0.002).Regardlessofsunexposure time,thegroupshadsimilarfrequenciesofinadequatevitaminDlevels(p=0.972).

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:SilvaCM,daSilvaSA,AntunesMM,SilvaGA,SarinhoES,BrandtKG.Doinfantswithcow’smilkproteinallergy haveinadequatelevelsofvitaminD?JPediatr(RioJ).2017;93:632---8.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:cris.marrocos@yahoo.com.br(C.M.Silva).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2017.01.006

Conclusions: LowervitaminDlevelswere foundininfantswith CMPA,especially thosewho were exclusivelyorpredominantlybreastfed,makingtheseinfants apossiblerisk groupfor vitaminDdeficiency.

©2017SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/ 4.0/).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Alergiaaleite; Lactente; VitaminaD; Aleitamento materno; Luzsolar

Lactentescomalergiaàproteínadoleitedevacaapresentamníveisinadequados

devitaminaD?

Resumo

Objetivo: Verificar se lactentescomalergia àproteínado leitede vaca(APLV) apresentam níveisinadequadosdevitaminaD.

Métodos: Estudotransversal,envolvendo120crianc¸asdeaté2anosdeidade,sendoumgrupo comAPLVeoutrodecomparac¸ão,captadasdosambulatóriosdeGastroenterologiaPediátrica, AlergologiaPediátricaePuericulturadeumhospitaluniversitário,noNordestebrasileiro.Foi aplicadoumformulárioecoletadasamostrassanguíneasparaaanálisedavitaminaD,sendo consideradosinadequadososníveis<30ng/mL.NíveisdevitaminaDforamexpressosemmédia edesviopadrão,eafrequênciadosgrausdesuficiênciaedemaisvariáveis,emproporc¸ões. Resultados: LactentescomAPLVquandocomparadosaossaudáveis,apresentaramumamenor média do nível da vitamina D (30,93 vs 35,29ng/mL) (p=0,041) e maior frequência de deficiência (20,3% vs 8,2) (p=0,049). Maior frequência de níveis inadequados de vitamina D foi observada nas crianc¸as com APLV que estavam em aleitamento materno exclu-sivo/predominante(p=0,002).Independentementedoperíododeexposic¸ãosolar,afrequência deumstatusinadequadodevitaminaDfoisemelhanteentreosgrupos(p=0,972).

Conclusões: MenoresníveisdevitaminaDforamobservadosemlactentescomAPLV, especial-mentenaquelasemaleitamentomaternoexclusivo/predominante,configurandoestecomoum possívelgrupoderiscoparaessadeficiência.

©2017SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigo OpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4. 0/).

Introduction

Currently,vitaminDdeficiencyhasbeenrecognizedasa fre-quentproblem,whichis observedin adults,children, and sometimesevenintheneonatalperiod.1Classically,vitamin Ddeficiencyisassociatedwithbonediseases,butinrecent yearsithasbeenassociatedwithseveralextraosseous out-comes,includingimmunediseases.2Itappearstooccurmore frequentlyin certaingroups of individuals; therefore, the EndocrinologySocietyrecommendsscreeningforvitaminD deficiencyonlyinthegroupofindividualsconsideredtobe atrisk.Thisriskgroupwouldcompriseindividualsofblack ethnicity,aswellasthosewhoareobese,pregnantand lac-tatingwomen, andindividuals withcertaindiseases, such asendocrineandrenaldiseases,amongothers.Individuals withcow’s milkproteinallergy(CMPA) arenotincludedin theriskgroup.3

Inturn,someinternationalstudies,mainlycarriedoutin children withtheimmediateforms of CMPA, mediatedby IgE,suggested a higherfrequency of vitamin D deficiency in this group.4---7 Low levels of vitamin D in children are associatedwithfactorssuchaspoormaternal---fetaltransfer duetomaternalhypovitaminosis,inadequatesunexposure, inappropriateuseofvitaminDsupplements,andlowdietary intake.1,8,9

Studies on vitamin D levels in children with CMPA are importanttoassesswhethertheyareariskgroupfor vita-minDdeficiency.Sincemoststudiesthatassessedvitamin D levels in children with CMPA were carried out in chil-dren without gastrointestinal manifestations,4---7 there are gapsonthe knowledge of this problem. Additionally, few studieshave been performed in children withCMPAliving in sunny regions, where adequate exposure to ultraviolet raysisassumed.Thepresentstudyaimedtoverifywhether infantswithCMPApresentinadequatelevelsofvitaminD.

Methods

Thiswasanobservational,cross-sectionalstudycomparing vitaminDlevelsinagroupofinfants withclinical diagno-sisofCMPAandagroupofhealthyinfants(controlgroup). The study wascarriedout fromMarch 2013 toApril 2015 inthepediatricgastroenterology,pediatricallergology,and pediatricoutpatientclinicsofHospitaldasClínicasat Uni-versidadeFederaldePernambuco(HC/UFPE).

bythemaincurrentguidelines.10,11 Thechallengetestwas contraindicatedbytheinvestigatorsinthefollowing situa-tions:reportof immediatemanifestationsassociatedwith apositive IgE result;late manifestationscompatible with CMPA,associatedwithmalnutrition.Thecomparisongroup consistedof61healthychildren.Childrenwithclinical sus-picionofother pathologiesor factorsthatcouldinfluence vitamin D levels, such asacute or chronic infectious dis-eases, other inflammatory bowel diseases, and renal or gastrointestinaldiseaseswereexcluded.

Fortheanthropometric evaluation,the infant’s weight wasobtainedandtheweight/age(W/A)indicatorproposed bytheWorldHealthOrganization(WHO)wasused.Forthe evaluationofW/A,thefollowingcutoffswereused:<−2 z-scoreforlow,≥−2and<+2z-scoreforage-appropriate,and ≥+2z-scoreforelevated.12

Regarding vitamin D, levels and degrees of sufficiency wereanalyzed,categorizedasinsufficient/deficientand suf-ficient. Vitamin D levels were considered deficient when 25(OH)D was ≤20ng/mL; insufficient, when between 21 and29ng/mL;andsufficient,when≥30ng/mL.3,13Forthis analysis,abloodsample (4mL)wascollectedbyatrained professional, stored in a tube with separator gel, and thentakentothelaboratoryconnectedwiththeresearch. 25(OH)Dwasmeasuredusingthechemiluminescence tech-niqueusingtheLIAISON®commercialkit.Parentsofchildren whohadinadequatelevelsofvitaminDwerewarnedofthe needforsupplementation.

TheWHOcategorizationwasusedtoclassifythecurrent practiceofbreastfeeding(BF);childrenwereconsideredas in exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) when theyreceived only breastmilk,withoutotherliquidsorsolids;inpredominant BF,whentheyreceived,inadditiontobreastmilk,wateror water-basedpreparations; insupplementedBF,when they received,inadditiontobreastmilk,anysolidorsemi-solid foodforthepurposeofcomplementingit,notreplacingit; andinmixedorpartialBF,whentheyreceivedbreastmilk andothertypesofmilk.14

When evaluating sun exposure, the guidelines of the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics (SBP) were used, which recommendsthatthechildshouldreceivedirectexposureof theskintosunlightafterthesecondweekoflife;aweekly quotaof30minofsunexposurewiththechildwearingonly diapersisconsideredsufficient.15

The construction of the database was performed using the Epi-Info software, version 6.04d (Epi-info 6.04, WHO/CDC, Atlanta, USA). Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software, version 13.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous varia-bles were tested for normality of distribution using the Kolmogorov---Smirnov test, being expressed as mean and standarddeviationwhenshowingasymmetricdistribution, andasmedianandquartileswhenthedistributionwas asym-metric. Differencesin frequency andassociation between categoricalvariableswereassessedbyPearson’schi-squared or Fisher’sexact tests, whenindicated. Forall tests,the significancelevelwassetat5%.

Thechildren’sparentsor tutorswereverballyinformed aboutthestudyaimsandsignedthefreeandinformed con-sentform.ThestudyprojectwasregisteredattheNational Committee of Research Ethics (CONEP/Plataforma Brasil) andsubmittedtotheapprovaloftheEthicsCommitteeon

ResearchinHumanBeingsoftheCentrodeCiênciasdaSaúde at Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, under CAAE No. 12878313.4.0000.5208/2013.

Results

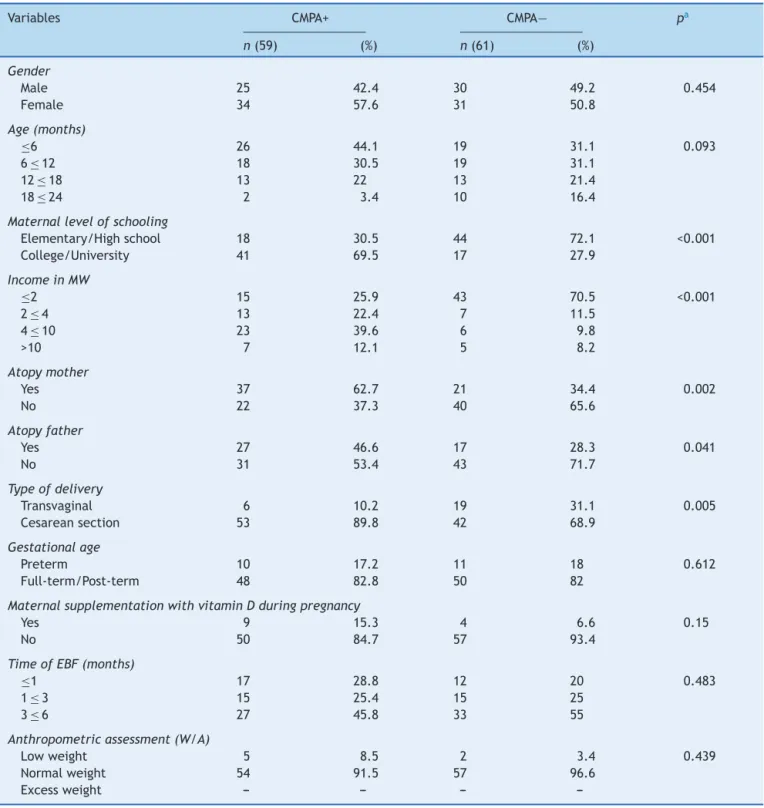

The medianageofthetotalsample was8.5months(P25: 6.0,P75:14.0),whereasinchildrenwithCMPAthemedian was7.0months(P25:4,P75:13),andinthecontrolgroup, itwas9.0months(P25:6.0,P75:16.0).Thesocioeconomic and biological characteristics of the sample areshown in

Table1,andamongthem,itwasobservedthatthe moth-ers of children withCMPAhad abetter level of schooling thanthoseofthechildreninthecomparativegroup(69.5% vs. 27.9,college/university level ofschooling),as wellas higher familyincome (51.7% vs.18%, >fourBrazilian mini-mumwages).Apredominanceofcesareandelivery(89.8%) wasobservedinthegroupofchildrenwithCMPA.Therewas alsoahigherfrequencyofatopyamongmothers(62.7%vs. 34.4%)andfathers(46.6%vs.28.3%)ofchildrenwithCMPA. When the nutritional status wasevaluated, a higher per-centageofnormalweightwasobservedinthesample,with similarfrequenciesinbothgroups(91.5%intheCMPAgroup and96.6%inthecontrolgroup).

InchildrenwithadiagnosisofCMPA,themostfrequent clinicalmanifestationswereoftheimmediatetype(59.3%): angioedema,urticariaandskin hyperemia,vomiting, diar-rhea,cough,andwheezing.Thelatemanifestationswere: regurgitationand vomiting compatiblewith gastroesopha-geal reflux disease (GERD), diarrhea,diarrhea withblood (compatible with colitis), proctitis, low weight gain or weight loss, excessive crying and abdominal distension, boweldisorders,andatopiceczema.Amongtheimmediate manifestations,themostprominentwereurticariain28.8%, angioedemain15.3%,andcoughin15.3%.Inthegroupwith latemanifestations,40.7%hadvomitinganddiarrhea,35.6% hadsignsofcolitis,and22%hadsymptomscompatiblewith GERD.

ThemeanlevelsofvitaminDamongchildrenwithCMPA were 30.93±12.33ng/mL and 35.29±10.74ng/mL in the control group (p=0.041). Fig.1 shows thefrequencies of thedifferentlevelsofvitaminDsufficiencyinbothgroups, indicating thatamongthetotalnumberofchildren,there was ahigher frequency of deficiency levels in thosewith CMPA(20.3%vs.8.2%;p=0.049).Itisnoteworthythatnone of thechildren werereceiving vitaminD supplementation at thetimeof theinterviewandonly nineof themothers ofchildrenwithCMPAreportedreceivingvitaminD supple-mentationduringthegestationalperiod.

Table1 SocioeconomicandbiologicalcharacteristicsofinfantswithCMPAandofthecontrolgroupfollowedattheoutpatient clinicofauniversityhospital,Recife-PE,Brazil(2013---2015).

Variables CMPA+ CMPA− pa

n(59) (%) n(61) (%)

Gender

Male 25 42.4 30 49.2 0.454

Female 34 57.6 31 50.8

Age(months)

≤6 26 44.1 19 31.1 0.093

6≤12 18 30.5 19 31.1

12≤18 13 22 13 21.4

18≤24 2 3.4 10 16.4

Maternallevelofschooling

Elementary/Highschool 18 30.5 44 72.1 <0.001

College/University 41 69.5 17 27.9

IncomeinMW

≤2 15 25.9 43 70.5 <0.001

2≤4 13 22.4 7 11.5

4≤10 23 39.6 6 9.8

>10 7 12.1 5 8.2

Atopymother

Yes 37 62.7 21 34.4 0.002

No 22 37.3 40 65.6

Atopyfather

Yes 27 46.6 17 28.3 0.041

No 31 53.4 43 71.7

Typeofdelivery

Transvaginal 6 10.2 19 31.1 0.005

Cesareansection 53 89.8 42 68.9

Gestationalage

Preterm 10 17.2 11 18 0.612

Full-term/Post-term 48 82.8 50 82

MaternalsupplementationwithvitaminDduringpregnancy

Yes 9 15.3 4 6.6 0.15

No 50 84.7 57 93.4

TimeofEBF(months)

≤1 17 28.8 12 20 0.483

1≤3 15 25.4 15 25

3≤6 27 45.8 33 55

Anthropometricassessment(W/A)

Lowweight 5 8.5 2 3.4 0.439

Normalweight 54 91.5 57 96.6

Excessweight --- --- ---

---CMPA,cow’smilkproteinallergy;MW,Brazilianminimumwages;EBF,exclusivebreastfeeding;W,weight;A,age.

a Pearson’schi-squaredorFisher’sexacttest.

In the group ofallergic children, the frequency ofsun exposure did not interfere with the level of vitamin D sufficiency; the results were similar in those with defi-ciency/insufficiency and in those with sufficient degrees (among those with deficient/sufficient degrees, 14 were adequately exposed to sunlight, whereas 12 were not; amongthose withsufficient degrees, 17 were adequately exposedand13werenot,p=0.972).

Discussion

0 10 30 50 70 90

20

20.3

8.2

40 60 80 100

%

79.7 91.8

Deficient

Case Control

Insufficient and sufficient

Levels of vitamin D pa = 0.049

Figure1 FrequenciesofvitaminDsufficiencylevelsininfantswithcow’smilkproteinallergyandinthecontrolgroup,treated atanoutpatientclinicinauniversityhospital,Recife,PE,Brazil(2013---2015).

aFisher’sexacttest.

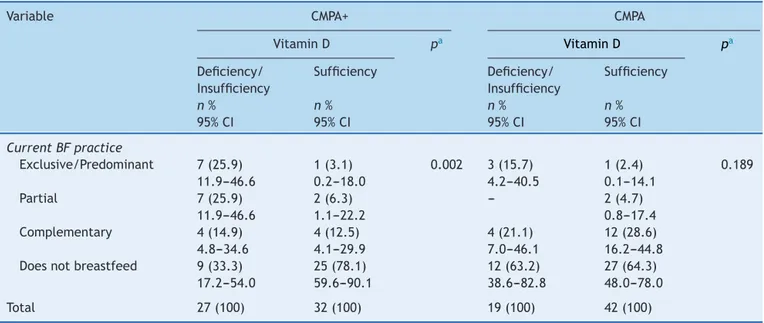

Table2 VitaminDstatusofinfantswithCMPAandofthecontrolgroupfollowedatanoutpatientclinicofauniversityhospital, inrelationtothefeedingpractice,Recife,PE,Brazil(2013---2015).

Variable CMPA+ CMPA

VitaminD pa VitaminD pa

Deficiency/ Insufficiency

Sufficiency Deficiency/ Insufficiency

Sufficiency

n% n% n% n%

95%CI 95%CI 95%CI 95%CI

CurrentBFpractice

Exclusive/Predominant 7(25.9) 1(3.1) 0.002 3(15.7) 1(2.4) 0.189 11.9---46.6 0.2---18.0 4.2---40.5 0.1---14.1

Partial 7(25.9) 2(6.3) --- 2(4.7)

11.9---46.6 1.1---22.2 0.8---17.4 Complementary 4(14.9) 4(12.5) 4(21.1) 12(28.6) 4.8---34.6 4.1---29.9 7.0---46.1 16.2---44.8 Doesnotbreastfeed 9(33.3) 25(78.1) 12(63.2) 27(64.3)

17.2---54.0 59.6---90.1 38.6---82.8 48.0---78.0

Total 27(100) 32(100) 19(100) 42(100)

CMPA,cow’smilkproteinallergy;BF,breastfeeding.

aPearson’schi-square.

inallergicchildren(30.93vs.35.29;p=0.041),reinforcing thetendencyofallergicchildrentohavelowervitamin lev-els.Somestudieshavealreadyinvestigatedtheassociation between vitamin D deficiency and food allergy, but most of them were performed in children withthe immediate formof CMPA, IgE-mediated.4---7 This study alsoraises the questionaboutthelateform,non-IgE-mediated,which usu-allymanifeststhroughgastrointestinalsymptoms.Thereis an empiricalbasis for believing that insufficient levelsof

ofthestudydidnotallowtoestablishacausalassociation betweenvitaminDdeficiencyandtheoccurrenceofallergy. Itcanbespeculatedthattheassociationmaybethe oppo-site,considering thatthepathogenesisofCMPAitselfmay have favoredlowvitamin Dlevels,both becauseitallows malabsorption and becauseit can be associated with the inflammatoryresponse.18

The systemic inflammatory response, which might be generated during the allergic process, may be associated withlow concentrations of fat-soluble vitamins,including vitaminD.18,19Thelowlevelscouldalsobeassociatedtothe factthatthemothersofchildrenwithCMPAinEBFadopted adietthatrestrictedcow’smilkanddairyproducts,without vitaminDsupplementation,afactalreadyassociatedwith deficienciesofvitaminDandothermicronutrients.20

The main sources of vitamin D for infants are dietary intake, sun exposure, and vitamin supplements.21 Breast milkcan provide a protective effectagainst the develop-ment ofseveral types of allergiesdue tothe presenceof immunologicalfactors and functional nutrients that favor a healthy microenvironment for immune system develop-ment and intestinal maturation.22 However, asit has low concentrationsofvitamin D,23 childrenreceivingBF, espe-ciallythoseinEBFandwithoutadequatesunexposure,may representagroupathigherriskforvitaminDdeficiency.24

Low levels of vitamin D were observed in allergic children who were receiving BF, and a higher fre-quency of deficient/insufficient levels of vitamin D was observedamongchildrenwithCMPAwhoweresubmittedto EBF/predominantBF (25.9%).Evidence suggeststhat chil-dren who develop CMPA, even thosein EBF, have genetic factorsthatpredisposethemtothisoutcome.24Itispossible that,inaninfantreceivingEBFwhoalreadyhasagenetic predispositiontoCMPA, the occurrence ofvitamin D defi-ciencyactsasatriggerforthedevelopmentofthedisease. Inthissense,itwasobservedthatoftheeightinfantswho wereinEBF/predominantBFanddevelopedCMPA(mostof themallergiccolitis),sevenwerefoundtohaveinadequate levelsofvitaminD.

Studies carried out in different countries suggest the needforsupplementationofinfantsreceivingBF,and some-timesofthemother,evenwhentheyliveinasunnyregion.25 Noneofthechildreninthisstudyreceivedvitamin supple-mentation, and only nine mothers of children with CMPA (15.3%) andfour mothers ofhealthy children (6.6%) were takingsupplementation.ItwasobservedthatinBrazil,the indicationofvitaminDsupplementationintheprenataland breastfeedingperiodsisnotyetacommonpractice,andthis perhapsneedstobeconsidered.

Sun exposure is considered one of the most important determinantsofvitaminDstatus.Infants’vitaminDlevels tendtodeclineoverthefirstfewmonthsoflifeiftheyare notexposedtosunlightoriftheydonotreceiveanadequate dietary intake of vitamin D.26 In the Northeast of Brazil, abundant solarirradiation occursduringmostof theyear. However,living in asunny regionmay notprotectinfants fromthisvitamindeficiency.Whenanalyzingtheassociation betweensunexposureandvitaminDlevelsinthisstudy,it wasobserved that adequate sun exposure did not ensure sufficientlevelsofvitaminD.

In a recent study carried out in this same region, insufficient levelsof vitamin D were also observed in the

mother/newbornbinomial,27corroboratingotherdatathat indicatethatevenincitieswithhighsolarirradiation,high frequencies of vitamin D deficiency may occur. The fact that sun exposure wasnot associated with adequate lev-elsof vitamin D in this study may have been due to the influence of other factors, such asthe time of day when thechildwasexposed,skincolor,andtheuseofsunscreen, whichwerenotpossibletobeanalyzed.Itisprobablethat fearofthesun’sharmfuleffectsontheskinhindered ade-quatesunexposure;infact,dermatologistsrecommendthat babiesagedupto6monthsshouldnotbeexposedtodirect sunlight.28

When analyzingtheresults ofthisstudy,itslimitations should be considered. The complexity of the problem to be assessed was one of the main difficulties found, and other factors that could be related to vitamin D levels were not controlled, such as the restriction of milk and dairyproducts in the maternal diet,the useof vitamin D supplementationduringpregnancy,andadherencetothese recommendations,aswellasthetypeofdeliveryandother aspects associated with the baby’s intestinal microbiota. Sample heterogeneity was considered one of the prob-lems due to individual differences of the disease. Social class bias may also have occurred, as families with bet-tersocioeconomic status might have sought the pediatric gastroenterology outpatient clinic, aiming at obtaining a medicalreporttoreceivethespecializedformulasprovided bythepublichealthcareservices.Difficultiesinherenttothe questionnaireapplicationmayalsohaveoccurred,sincethe questionnairewasappliedbytwodifferentresearchers;the reliabilityoftheinformationprovidedbythemothersshould also be considered. The sample size was small, perhaps insufficient to subsidize changes in guidelines previously establishedbyregulatorysocieties; however,theyare suf-ficienttoserveasawarningandtotriggercomplementary randomizedandprospectivestudiesonthesubject.Alarger samplesizecouldallowCMPAinfantstobegroupedand ana-lyzedaccording tothe clinical manifestations (immediate andlate),consideringthedifferentimmunological mecha-nismsinvolvedinthepathogenesisofCMPA.

Thelackofaconsensusregardingthecutoffpointsthat define vitaminD status wasalso considered tobe abias, makingitdifficult tounderstandwhich valueswouldhave apathogeniceffectandcompromisingthecomparisonwith studiesthatusedother referencevalues.Whilethe Amer-icanEndocrinologySociety states thatdeficient levelsare thosebelow20ng/mLandsufficientvaluesarethoseequal toorgreaterthan30ng/mL,29 theUSInstituteofMedicine (2010)considerslevelsabove20ng/mLasappropriate.30In thisstudy,sufficientlevelswerethoseequaltoor greater than30ng/mL.

sourceofvitaminD,especiallyininfantsinEBF,androutine supplementationshouldbeevaluated. Itis suggestedthat otherstudiesbecarriedouttodemonstratetheassociation andbetterelucidatethefactorsassociatedwithinadequate vitaminDlevelsininfantswithCMPA.

Funding

Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tec-nológico (CNPq), through financial aid from the uni-versal notice of 2012/2013 under registration number 488488/2013-3.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.Merewood A, Mehta SD, Grossman X, Chen TC, Mathieu JS, Holick MF, et al. Widespread vitamin D deficiency in urbanMassachusettsnewbornsand theirmothers.Pediatrics. 2010;125:640---7.

2.RosenCJ,AdamsJS,BikleDD,BlackDM,DemayMB,MansonJE, etal.ThenonskeletaleffectsofvitaminD:anendocrinesociety scientificstatement.EndocrRev.2012;33:456---92.

3.Maeda SS,BorbaVZ,CamargoMB,SilvaDM, BorgesJL, Ban-deira F, et al. Recomendac¸ões da Sociedade Brasileira de EndocrinologiaeMetabologia(SBEM)paraodiagnósticoe trata-mento da hipovitaminose D. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2014;58:411---33.

4.AllenKJ,KoplinJJ,PonsonbyAL, GurrinLC,WakeM, Vuiller-min P, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency is associated with challenge-provenfoodallergyininfants.JAllergyClinImmunol. 2013;131:1109---16.

5.Mullins RJ, Camargo CA. Latitude, sunlight, vitamin D, and childhoodfoodallergy/anaphylaxis.CurrAllergyAsthmaRep. 2012;12:64---71.

6.OsborneNJ,UkoumunneOC,WakeM,AllenKJ.Prevalenceof eczemaandfoodallergyisassociatedwithlatitudeinAustralia. JAllergyClinImmunol.2012;129:865---7.

7.ShariefS,JariwalaS,KumarJ,MuntnerP,MelamedML. Vita-minDlevelsandfoodandenvironmentalallergiesintheUnited States:resultsfromNHANES2005---2006.JAllergyClinImmunol. 2011;127:1195---202.

8.ThorisdottirB,GunnarsdottirI,SteingrimsdottirL,PalssonGI, Thorsdottir I. Vitamin D intake and status in 12-month-old infantsat63---66◦N.Nutrients.2014;6:1182---93.

9.ChoiYJ,KimMK,JeongSJ,Vitamin.Ddeficiencyininfantsaged 1to6months.KoreanJPediatr.2013;56:205---10.

10.KoletzkoS,NiggemannB,AratoA,DiasJA,HeuschkelR,Husby S,et al.Diagnosticapproachand managementofcow’s-milk proteinallergyininfantsandchildren:ESPGHANGICommittee PracticalGuidelines.JPGN.2012;55:221---9.

11.FiocchiA,BrozekJ,SchünemannH,BahnaSL,BergA,BeyerK, etal.WorldAllergyOrganization(WAO)diagnosisandrationale foractionagainstcow’smilkallergy(DRACMA)guidelines.World AllergyOrganJ.2010;3:57---161.

12.W.H.O.,MulticentreGrowthReferenceStudyGroup.WHOchild growthstandardsbasedonlength/height,weightandage.Acta Paediatr.2006;450:S76---85.

13.HolickMF.VitaminDstatus:measurement,interpretation,and clinicalapplication.AnnEpidemiol.2009;19:73---8.

14.MinistériodaSaúde(BR),SecretariadeAtenc¸ãoàSaúde, Depar-tamento de Atenc¸ão Básica Saúde da Crianc¸a. Aleitamento maternoealimentac¸ãocomplementar. Brasília:Ministério da Saúde;2015.

15.Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria (BR), Departamento de Nutrologia. Manual de orientac¸ão para a alimentac¸ão do lactente,dopré-escolar,doescolar,doadolescenteenaescola. RiodeJaneiro:SBP;2012.

16.SuainiNH,ZhangY,VuillerminPJ,AllenKJ,HarrisonLC.Immune modulationbyvitaminDanditsrelevancetofoodallergy. Nutri-ents.2015;7:6088---108.

17.ChunRF, LiuPT,ModlinRL,AdamsJS,HewisonM.Impactof vitaminDonimmunefunction:lessonslearnedfrom genome-wideanalysis.FrontPhysiol.2014;5:151.

18.ValentaR,HocwalnnerH,LinhartB,PahrS.Foodallergies:the basics.Gastroeneterology.2015;148:1120---31.

19.GashutRA,TalwarD,KinsellaJ,DuncanA,McMillanDC.The effectofthesystemicinflammatoryresponseonplasma vita-min25(OH)Dconcentrationsadjustedforalbumin.PLoSOne. 2014;9:1---7.

20.MarangoniF,CetinI,VerduciE,CanzoneG,GiovanniniM,Scollo P,etal.Maternaldietandnutrientrequirementsinpregnancy andbreastfeedinganItalianConsensusDocument. Nutrients. 2016;8:piiE629.

21.GreerFR.IssuesinestablishingvitaminDrecommendationsfor infantsandchildren.AmJClinNutr.2004;80:S1759---62. 22.AndreasNJ,KampmannB,MehringLe-DoareK.Humanbreast

milk:a reviewonitscompositionand bioactivity.EarlyHum Dev.2015;9:629---35.

23.DecsiT,LohnerS.Gapsinmeetingnutrientneedsinhealthy toddlers.AnnNutrMetab.2014;65:22---8.

24.HollisBW,WagnerCL,HowardCR,EbelingM,SharyJR,Smith PG,et al.Maternal versusinfantvitaminD supplementation during lactation: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136:625---34.

25.Hong X, Wang G, Liu X, Kumar R, Tsai H-J, Arguelles L, etal. Genepolymorphismsbreast-feeding,and development of sensitization in early childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:374---81.

26.Salameh K, Al-Janahi NS, Reedy AM, Dawodu A. Prevalence andriskfactorsforlowvitaminDstatusamongbreastfeeding mother-infantdyadsinanenvironmentwithabundantsunshine. IntJWomensHealth.2016;8:529---35.

27.LipsP,van SchoorNM, de JonghRT. Diet, sun,and lifestyle as determinants of vitamin D status. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1317:92---8.

28.PenaHR,deLimaMC,BrandtKG,deAntunesMM,daSilvaGA. Influenceofpreeclampsiaandgestationalobesityinmaternal and newbornlevelsof vitaminD.BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:112.

29.HolickMF,BinkleyNC,Bischoff-FerrariHA,GordonCM,Hanley DA,HeaneyDA,etal.Evaluation,treatment,andprevention ofvitaminDdeficiency:anEndocrineSocietyclinicalpractice guideline.JClinEndocrinolMetab.2011;96:1911---30. 30.HewisonM.VitaminDandimmunefunction:anoverview.Proc