w w w . r e u m a t o l o g i a . c o m . b r

REVISTA

BRASILEIRA

DE

REUMATOLOGIA

Original

article

Which

is

the

best

cutoff

of

body

mass

index

to

identify

obesity

in

female

patients

with

rheumatoid

arthritis?

A

study

using

dual

energy

X

-ray

absorptiometry

body

composition

Maria

Fernanda

B.

Resende

Guimarães

a,∗,

Maria

Raquel

da

Costa

Pinto

a,

Renata

G.

Santos

Couto

Raid

b,

Marcus

Vinícius

Melo

de

Andrade

c,

Adriana

Maria

Kakehasi

a,daUniversidadeFederaldeMinasGerais(UFMG),HospitaldasClínicas,Servic¸odeReumatologia,BeloHorizonte,MG,Brazil

bUniversidadeFederaldeMinasGerais(UFMG),FaculdadedeTecnologiaemRadiologia,BeloHorizonte,MG,Brazil

cUniversidadeFederaldeMinasGerais(UFMG),FaculdadedeMedicina,DepartamentodeClínicaMédica,BeloHorizonte,MG,Brazil

dUniversidadeFederaldeMinasGerais(UFMG),FaculdadedeMedicina,DepartamentodoAparelhoLocomotor,BeloHorizonte,MG,

Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received12March2015 Accepted16September2015 Availableonline10March2016

Keywords:

Rheumatoidarthritis Obesity

Bonedensitometry Bodycomposition Bodymassindex

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Introduction:Standardanthropometricmeasuresusedtodiagnoseobesityinthegeneral

populationmaynothavethesameperformanceinpatientswithrheumatoidarthritis.

Objective:Todeterminecutoffpointsforbodymassindex(BMI)andwaistcircumference

(WC)fordetectingobesityinwomenwithrheumatoidarthritis(RA)bycomparingthese standard anthropometricmeasuresto a dual-energyX-rayabsorptiometry (DXA)-based obesitycriterion.

Patientsandmethod:AdultfemalepatientswithmorethansixmonthsofdiagnosisofRA

underwentclinicalevaluation,withanthropometricmeasuresandbodycompositionwith DXA.

Results:Eightytwopatientswereincluded,meanage55±10.7years.Thediagnosisofobesity

inthesamplewasabout31.7%byBMI,86.6%byWCand59.8%byDXA.ConsideringDXA asgoldenstandard,cutoffpointswereidentifiedforanthropometricmeasurestobetter approximateDXAestimatesofpercentbodyfat:forBMIvalue≥25kg/m2wasthebestfor definitionofobesityinfemalepatientswithRA,withsensitivityof80%andspecificityof 60%.ForWC,with80%ofsensitivityand35%ofspecificity,thebestvaluetodetectobesity was86cm.

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:mfbresende@yahoo.com.br(M.F.Guimarães). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbre.2016.02.008

Conclusion: Alargepercentageofpatientswereobese.Thetraditionalcutoffpointsusedfor obesitywerenotsuitableforoursample.ForthisfemalepopulationwithestablishedRA, BMIcutoffpointof25kg/m2 andWCcutoffpointof86cmwerethemostappropriateto detectobesity.

©2016ElsevierEditoraLtda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Qual

o

melhor

ponto

de

corte

de

índice

de

massa

corporal

para

diagnosticar

a

obesidade

em

mulheres

com

artrite

reumatoide?

Um

estudo

que

usa

a

composic¸ão

corporal

pela

absorciometria

com

raios

X

de

dupla

energia

Palavras-chave:

Artritereumatoide Obesidade

Densitometriaóssea Composic¸ãocorporal Índicedemassacorporal

r

e

s

u

m

o

Introduc¸ão: Medidasantropométricasuniversalmenteusadasparadiagnosticarobesidade

napopulac¸ãogeralpodemnãoapresentaramesmaperformanceempacientescomartrite reumatoide.

Objetivos: Determinarpontosdecortedoíndicedemassacorporal(IMC)eda

circunfer-ência decintura(CC) paradetecc¸ãodeobesidadeemmulherescomartritereumatoide (AR)pormeiodacomparac¸ãodessasmedidasantropométricashabituaiscomosíndices deadiposidadeobtidospeladensitometriaósseaporduplaemissãoderaiosX(DXA).

Pacientesemétodo: MulheresadultascommaisdeseismesesdediagnósticodeARforam

submetidas a avaliac¸ãoclínica commedidas antropométricase à DXAcomexame da composic¸ãocorporal.

Resultados: Foramincluídas82pacientes,médiade55±10,7anos.Odiagnósticode

obesi-dadenaamostrafoide31,7%peloIMC,86,6%pelacircunferênciadecinturae59,8%pela DXA.ConsiderandoaDXAopadrão-ouro,ovalordeIMCacimade25kg/m2foiomais ade-quadoparadefinic¸ãodeobesidadenaspacientescomAR,apresentousensibilidadede80% eespecificidadede60%.Damesmaforma,paraaCC,com80%desensibilidadeede35%de especificidade,ovalorencontradofoide86cmparasedetectaraobesidade.

Conclusão: Foi elevado o porcentual de pacientes obesas. Os pontos de corte

tradi-cionalmenteusadosparaobesidadenãoforamadequadosparanossaamostra.Paraessa populac¸ãodepacientesfemininascomdiagnósticodeAR,opontodecortede25kg/m2para IMCede86cmparaCCfoiomaisadequadoparadefinirobesidade.

©2016ElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCC BY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Obesityand rheumatoid arthritis(RA) havebeen shown to berelatedindifferentways.Thefirstconditionseemstobe relatedtoanincreasedriskofdevelopmentofthesecond dis-ease.Recentmeta-analysisthatincluded11studiesshowed thatobesesubjectswithBMI≥30kg/m2hadahigherrelative riskfordevelopingRA.1

Inpatientswiththeestablisheddisease,theinflammatory processisableofalteringbodycomposition,leadingtoobesity withincreasedabdominalfat andlossofleanbody mass.2

Thisdecreaseinleanbodymass,alongwiththeincreaseinfat massandincentralobesity,mayberelatedtotheincreased cardiovascularmorbidityandalsowithfunctionaldecline.3

In cases of RA, the occurrence of body fat accumu-lation without a significant increase in body weight is a condition known as rheumatoid cachexia,4,5 whose

esti-mated prevalence ranges from 10 to 67%.6 In a setting

of chronic inflammation, high levels of cytokines cause

metabolicchanges,whichcanresultinthealterationsabove mentioned.7,8

Moreover,accordingtotheUSCenterofDiseaseControl (CDC),9theprevalenceofobesityinpatientswithrheumatoid

arthritisis54%higherthaninRA-freeindividuals.A multicen-terstudyfoundaprevalenceof18%ofobesityinapopulation withRA,10whileanotherstudyfoundaprevalenceof31%.11

EpidemiologicaldataconsideredRAasanindependentrisk factorforcardiovasculardisease(CVD),andoneofthemain causes ofdeathinpatientswiththat disease.12–14 A

meta-analysisof24studiesofpatientswithRAshowedanincrease of 50% in the risk ofdeath from cardiovascular causes in general.15

Obesity can contribute to increasing the risk of CVD developmentaswellasoftypeIIdiabetesmellitus(DMII), dyslipidemia,andhypertension(HBP).16,17

negatively influence the course of the disease, functional capacity ofpatients, as well as disease activity.18,20 Obese

patientsarenot-sogoodrespondentstotheuseofanti-TNF agents,andarelesslikelytoachieveremissionwiththeuse ofthese drugs.21 Onestudyfoundadecreased responseto

treatmentwithacombinationofsyntheticdisease-modifying anti-rheumaticdrugsinpatientswithhighBMIs.22

Obesity, definedas an increase infat insufficient level tocauseadversehealthconsequences,isusuallydiagnosed byanthropometricmeasurementsofbodymassindex(BMI), which is calculated as weightin kilograms divided bythe squareofheightinmeters(kg/m2),andofwaistcircumference (WC).23

BMIiseasy to performand agood indicator ofobesity, but does not have an accurate correlation with body fat. Thisindicator is notable to distinguishbetween fat mass andleanmass,anddonotnecessarilyreflectsthe distribu-tionofbodyfat.24Identifyingfatdistributionisimportantin

theevaluationofoverweightand obesity,asvisceral (intra-abdominal)fatisariskfactorforCVD,regardlessoftotalbody fat.Individualswiththe same BMImayhavedifferent lev-elsofvisceralfatmass;andthisrelationshipbetweenweight andheightmay notbeabletoreflectthosebody composi-tionchanges oftenfoundinpatientswithRA.8 For agiven

valueofBMI,body fatmay differ,andthereis evidenceof higher percentages of body fat in patients with RAversus

controls.25

Dual-energyX-rayabsorptiometry(DXA)isamoreaccurate method than BMI measurement to assess body composi-tion, both in young and in older subjects; this method is sensitivetosmall changes inbody composition.26–28 In RA

patients, theassessmentofbody compositionby DXAwas abnormal,withadecreaseinleanbodymassandanincrease offatmass,especially inpatientswithinnormalrange for BMI.29,30

Theaimofthisstudyistoevaluatethecorrelationbetween conventional anthropometric measurements (BMI and WC) and total fat percentage and adiposity indexes obtained throughbody composition byDXA.Another objective is to identifytheneedof,anddetermine,newcutoffpointsforBMI andWCforobesitydetectioninwomenwithRA.

Patients

and

methods

Female patients with rheumatoid arthritis defined accord-ing totheAmerican CollegeofRheumatology (ACR)198731

ortoACR/EULAR201032classificationcriteria,withover six

monthsofsymptoms,andagedover18yearsoldwere con-secutivelyinvitedtoparticipateinthisstudy.Patients with otherconnectivetissuediseases(overlapsyndromes),except forsecondarySjögren’ssyndrome;withpresenceofa pace-maker,implanteddefibrillator,andorthopedicprosthesis,or any metallic object (pins, screws)from orthopedic surgery wereexcluded fromthis study,due tointerferenceinbody compositionexaminationbyDXA.Beforeperformingany pro-cedure,allparticipantssignedainformedconsentform(FICF) previously approved by the Research Ethics Committee of UFMG.

Allpatientsunderwentclinicalevaluation,whichincluded swollen/painful joint counts. Information related to the disease,diagnosticcriteria,clinicaland laboratory manifes-tations, the presence of extra-articular manifestations, comorbidities, and current and previous treatments, was obtained from an interview and by medical record review.

Anthropometric measurements and bone densitometry withbodycompositionwereperformedonthesame assess-ment day. The participants were weighed barefooted and withoutheavyclothingonaFilizolascale(1–200kg,withan errormarginof50g)intendedexclusivelyforweighing peo-ple.Thesubject’sheightwasmeasuredwiththestadiometer coupledtothesameFilizolascale.TheBMIcalculationwas performedaccordingtotheformula:BMI=weight(kg)/height (m2).

The following BMI ranges were adopted: normal, BMI=18.5–24.9kg/m2; overweight, BMI=25–29.9kg/m2; and obesity,BMI≥30kg/m2,asrecommendedbytheWorld HealthOrganization.33

WCwas performedusingaplastictapemeasure,which wasappliedmidwaybetweenthelowestribandtheiliaccrest withthesubjectstanding,andrepresentedthehorizontal dis-tancearoundtheabdomen.Presenceofabdominalorcentral obesity was considered in women whose waist circumfer-ence≥80cm.34

Wealso calculatedthe conicityindex, whichis another waytoestimateabdominalobesity.Thisindexwasdeveloped fromageometricratiomodel,andwascalculatedusingthe patient’swaistcircumference,weightandheightthroughthe followingformula:35

waistcircumference(cm)

0.109×

weight(kg)height(m)

Body composition was measured byDXA (Discovery W Hologic densitometer [Bedford, MA, USA], v. 3.3.0), and the results were always interpreted by the same trained researcher.Themeasurementswereperformedwiththe sub-jectsupine,afterremovingallmetalfittings,andlastedsix minutes. We used Bray GA’s definition of obesity by DXA, that considers the patient’s gender and age group. In this definition,thepercentageoffatconsideredrepresentativeof obesityvariesfrom39to43%inwomen,accordingtotheirage group.36

Statistical

analysis

The descriptive analysis was performed using mean and standarddeviationforcontinuousvariablesandpercentages forbinaryvariables.Anthropometricvariableswerecorrelated (Spearmanmethod)tototalfatpercentageobservedwithDXA. Theoptimalcutoffpointsofanthropometricvariableswere determinedusingROCcurves,andwiththefindingofpoints thatdeterminedpresetsensitivitiesof80%and90%for detec-tionofobesitydiagnosedwithDXA.

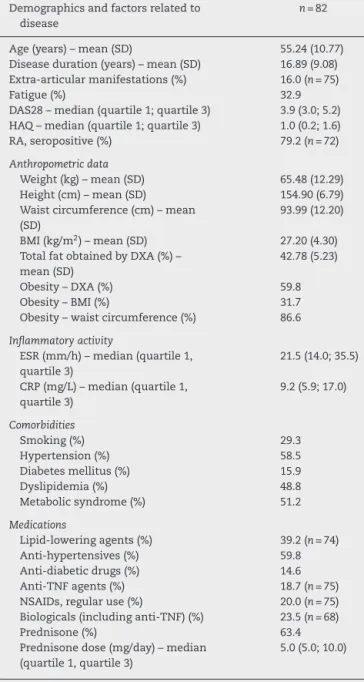

Table1–Demographicandclinicalcharacteristicsof studypopulation.

Demographicsandfactorsrelatedto disease

n=82

Age(years)–mean(SD) 55.24(10.77)

Diseaseduration(years)–mean(SD) 16.89(9.08)

Extra-articularmanifestations(%) 16.0(n=75)

Fatigue(%) 32.9

DAS28–median(quartile1;quartile3) 3.9(3.0;5.2)

HAQ–median(quartile1;quartile3) 1.0(0.2;1.6)

RA,seropositive(%) 79.2(n=72)

Anthropometricdata

Weight(kg)–mean(SD) 65.48(12.29)

Height(cm)–mean(SD) 154.90(6.79)

Waistcircumference(cm)–mean

(SD)

93.99(12.20)

BMI(kg/m2)–mean(SD) 27.20(4.30)

TotalfatobtainedbyDXA(%)–

mean(SD)

42.78(5.23)

Obesity–DXA(%) 59.8

Obesity–BMI(%) 31.7

Obesity–waistcircumference(%) 86.6

Inflammatoryactivity

ESR(mm/h)–median(quartile1, quartile3)

21.5(14.0;35.5)

CRP(mg/L)–median(quartile1, quartile3)

9.2(5.9;17.0)

Comorbidities

Smoking(%) 29.3

Hypertension(%) 58.5

Diabetesmellitus(%) 15.9

Dyslipidemia(%) 48.8

Metabolicsyndrome(%) 51.2

Medications

Lipid-loweringagents(%) 39.2(n=74)

Anti-hypertensives(%) 59.8

Anti-diabeticdrugs(%) 14.6

Anti-TNFagents(%) 18.7(n=75)

NSAIDs,regularuse(%) 20.0(n=75)

Biologicals(includinganti-TNF)(%) 23.5(n=68)

Prednisone(%) 63.4

Prednisonedose(mg/day)–median

(quartile1,quartile3)

5.0(5.0;10.0)

DAS28, Disease Activity Score; HAQ, Health Assessment

Ques-tionnaire;RA,rheumatoidarthritis;BMI,bodymassindex;DXA,

dual-energyX-rayabsorptiometry;ESR,erythrocytesedimentation

rate; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatorydrug.

Standarddeviationinparenthesesforcontinuousvariables.

Ethics

ThisstudywasapprovedbytheResearchEthicsCommitteeof UniversidadeFederaldeMinasGerais(UFMG)onJanuary10, 2012,withanaddendumandFICFapprovedonFebruary20, 2013.

Results

Eighty-twowomenwithmeanage55±10.7yearsandmean diseasedurationof16±9.08years,wereincludedinthisstudy.

Table2–Spearmancorrelationbetweenanthropometric measurementsforwaistcircumferenceandbodymass indexandtotalfatpercentageobtainedbyDXA.

Women (n=82)

Waistcircumference(cm) 0.482+

BMI(kg/m2) 0.510*

+ p<0.05. ∗ p<0.001.

Table3–SensitivityandspecificityBMI(kg/m2)in obesitydetectiondiagnosedbyDXA.Usualcutoffpoint (BMI=30)andoptimalpointsfound.

Women(n=82)

BMI Specificity Sensibility

30 76% 37%

25 58% 82%

23 36% 92%

ThiscohorthadameanBMIof27.2±4.3kg/m2,ameanwaist

circumferenceof94±12.2cm,andameanconicityindexof 1.33.Thedemographiccharacteristicsandfactorsrelatedto thediseasearelistedinTable1.Theobesityratefoundvaried accordingtodifferentcriteria:31.7%byBMI,86.6%byWC,and 59.8%byDXA.Thecorrelationsbetweenthefollowing clini-calvariableswereevaluated:diseaseduration,DAS28,HAQ, CRP,ESRandcumulativedoseofprednisone,bothwithBMI and withbody fatbyDXA. Noneofthesecorrelations was statisticallysignificant.

Table2showsSpearmancorrelationsbetweentotalfat per-centageobtainedbyDXAandWCandBMI.Onecanperceive thatallcorrelationsobtainedweresignificant(˛=5%)andBMI correlated morestronglywithtotalfatpercentageobtained

byDXAversusbyWC.Thecorrelationbetweenconicityindex

andtotalfatbyDXAwasalsopositive,withstatistical signif-icance(+0.2350withp=0.019);however,thisvaluewaslower thanthatforthecorrelationwithBMI.

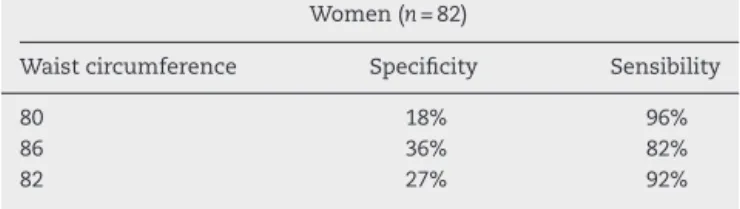

To determine the optimalcutoffpoints ofBMI and WC forobesitydetectioninpatientswithRA,theconstructionof ROCcurvesshowedcutoffvaluespresenting80%and90%of sensitivity. TheROCcurves showthat, forthedesired sen-sitivityvalues,BMIisabetterdiscriminatorofobesitythan WC,thankstoitshigherspecificityforthesamesensitivity values.

Table4–Sensitivityandspecificityofwaist

circumference(cm)inobesitydetectiondiagnosedby DXA.Usualcutoffpoint(80cmforwomen)andoptimal pointsfound.

Women(n=82)

Waistcircumference Specificity Sensibility

80 18% 96%

86 36% 82%

82 27% 92%

Discussion

TheobesityrateinthispopulationofpatientswithRAwas high;aboutonethirdwiththeuseoftheBMIdefinition,60%by DXA,andmorethan80%accordingtoWC.ThestudybyGiles etal.30reportedthat33%ofwomenand36%ofmenwithRA

wereregardedasobesebyBMI,and57%ofthesepatientswere deemedobesebyDXA.Katzetal.havedescribedobesityby BMIin28.4%;ontheotherhand,theseauthorsreached58.2% byDXAinthepopulationstudied.39Inrelationtoobesity

fre-quencybyWC,thevaluefoundwashigherthanthatdescribed intheliterature.24WiththeuseofWC,Katzetal.usedthe

obesitycriterionof88cmforwomen,39,40whereasthepresent

studyusedacutoffpointof80cmbyWC–alevelmorerecently recommendedbytheInternationalDiabetesFederation(IDF) in2006.34

When using DXA asthe gold standard for detection of obesity,werealizethattheprevalenceofthisconditionwas underestimatedbyBMIand overestimatedbyWC.Theuse ofa BMI>30kg/m2 had a sensitivity<40%; and the use of WC>80cm for women showed specificity<20%,clearly an overestimate ofthe number ofobese women in the study group.

One possible explanation for the underestimation seen withtheuseofBMIisthatthisindicatorlackstheabilityto considerthelossofleanbodymassconcomitantlytofatmass gaininindividualswithRA.AsforWC,itmaybethatits rec-ommendedthresholdforwomenisunreasonablylow(80cm), avaluewhichlacksspecificity.

IndeterminingthecutoffpointsofBMIand WCforthis femalepopulationwithRA,weemployedsensitivityvaluesof 80and90%,becauseourunderstandingisthatthese anthro-pometricmeasurementsshould beusedto screenpatients withRA;therefore,ahighsensitivityisacriticalfactor.Then, wecomparedourfindings tothose commonlyusedas cut-offpointsofBMIand WC,achieving the newcutoffpoints suggestedintheresults.

Our results suggest the use of a BMI>25kg/m2 as the thresholdforwomen,becausethis valueresultedina sen-sitivityof82%andinaspecificityof58%inthediagnosisof obesity.ForWC,wesuggesttheuseof86cmfordefinitionof obesity,resultingin82%ofsensitivityand36%ofspecificity.

Theresultsfoundinthisstudy areinlinewiththoseof otherauthorswhosuggestreviewingcutoffpointsofBMIand WCinpatientswithRA.Katzetal.proposedacutoffpointfor obesityinwomenof26.1kg/m2forBMIandof83cmforWC.24

Stavropoulos-Kalinoglouetal.suggestedadecreaseof2kg/m2 inBMIforRApatients,inordertoestablishthepresenceof

obesity.4 In this way,oneperceives auniversal acceptance

oftheconceptthatobesityinRApatientsmustbehandled inanearlyandintensivemanner.Lossofmusclemassand fat infiltrationin themuscle, resulting from inflammation, mayexplainthehigherpercentageoffat,despiteaBMIvalue withinthenormalrange.

Onelimitationofourstudyisitssamplesize;thissuggests thattheresultsobtainedarewaitingforexternalvalidation. The non-inclusion of male patients is another important limitation.Itisnoteworthy,however,thattheprevalenceof femalepatientsseemstoconstitutetheabsolutemajorityin RAcohortsinourpopulation.Inthemultinationalcohortof Latin-Americanpatients(GLADAR),theprevalenceoffemale patientswas85%.41Anotheraspecttoconsideristhatinour

studyagroupofpatientswasexcludedforlackingtheabilityto beexaminedbyDXA;thismayhaveleftoutagroupofpatients withcomorbidities,orwithadiseaseofgreaterseverity.

This sample consisted of patients with long disease duration (mean, 16 years) and high prevalence for use of corticosteroids (63.4%). The statistical analysis showed no correlationbetweendiseaseduration orcumulativedoseof corticosteroidswithBMIorwithtotalfatpercentagemeasured byDXA.Inourstudy,itwasfoundthatbodyfatisincreased inagroupoflong-termRApatients,andotherauthorshave demonstratedthatevenpatientswithearlyRAhavetheirtotal fatincreasedwhenmeasuredbyDXAversuscontrols.42

Conclusions

ConsideringDXAasthegoldstandard,thecutoffpoints con-ventionallyusedforobesitythroughanthropometricindexes werenotsuitableforourRApatients.

BMIwasthebestpredictorofobesityinpatientswithRA

versus WC, showinga bettercorrelation withtotal fat

per-centageobtainedbyDXA.BMIvaluesabove25kg/m2suggest alertnesstooptimizethetreatmentbystrengtheningthegoals forsteroiddiscontinuation,tofightagainstsedentarylifestyle, andnutritionalguidance.

Itissuggestedthat thisnewBMIcutoffpointshouldbe adoptedinclinicalpracticewhenapproachingfemalepatients withRA,inordertoidentifythoseoverweightsubjectsandalso topromoteintensiveinterventionsforbettercardiovascular outcomes.

Funding

FundsremainingfromSBR.

Conflict

of

interests

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

reviewanddose–responsemeta-analysis.ArthritisResTher. 2015;17:86.

2. ArshadA,RashidR,BenjaminK.Theeffectofdiseaseactivity onfat-freemassandrestingenergyexpenditureinpatients withrheumatoidarthritisversusnoninflammatory arthropathies/softtissuerheumatism.ModRheumatol. 2007;17:470–5.

3. ElkanAC,EngvallIL,CederholmT,HafströmI.Rheumatoid cachexia,centralobesityandmalnutritioninpatientswith low-activerheumatoidarthritis:feasibilityofanthropometry, mininutritionalassessmentandbodycomposition

techniques.EurJNutr.2009;48:315–22.

4. Stavropoulos-KalinoglouA,MetsiosGS,KoutedakisY,Nevill AM,DouglasKM,JamurtasA,etal.Redefiningoverweightand obesityinrheumatoidarthritispatients.AnnRheumDis. 2007;66:1316–21.

5. EngvallIL,ElkanAC,TengstrandB,CederholmT,BrismarK, HafstromI.Cachexiainrheumatoidarthritisisassociated withinflammatoryactivity,physicaldisability,andlow bioavailableinsulin-likegrowthfactor.ScandJRheumatol. 2008;37:321–8.

6. RoubenoffR,RoubenoffRA,WardLM,HollandSM,Hellmann DB.Rheumatoidcachexia:depletionofleanbodymassin rheumatoidarthritis.Possibleassociationwithtumor necrosisfactor.JRheumatol.1992;19:1505–10.

7. Stavropoulos-KalinoglouA,MetsiosGS,KoutedakisY,Kitas GD.Obesityinrheumatoidarthritis.Rheumatology(Oxford). 2011;50:450–62.

8. SummersGD,DeightonCM,RennieMJ,BoothAH.

Rheumatoidcachexia:aclinicalperspective.Rheumatology (Oxford).2008;47:1124–31.

9. LiaoKP,SolomonDH.Traditionalcardiovascularriskfactors, inflammationandcardiovascularriskinrheumatoidarthritis. Rheumatology(Oxford).2013;52:45–52.

10.NaranjoA,SokkaT,DescalzoMA,Calvo-AlénJ,

Hørslev-PetersenK,LuukkainenRK,etal.Cardiovascular diseaseinpatientswithrheumatoidarthritis:resultsfrom theQUEST-RAstudy.ArthritisResTher.2008;10:R30.

11.ArmstrongDJ,McCauslandEM,QuinnAD,WrightGD.Obesity andcardiovascularriskfactorsinrheumatoidarthritis. Rheumatology(Oxford).2006;45:782,authorreply782–783. 12.MeuneC,TouzéE,TrinquartL,AllanoreY.Trendsin

cardiovascularmortalityinpatientswithrheumatoid arthritisover50years:asystematicreviewandmeta-analysis ofcohortstudies.Rheumatology(Oxford).2009;48:1309–13. 13.GabrielSE,CrowsonCS,KremersHM,DoranMF,TuressonC,

O’FallonWM,etal.Survivalinrheumatoidarthritis:a population-basedanalysisoftrendsover40years.Arthritis Rheum.2003;48:54–8.

14.PincusT,CallahanLF,SaleWG,BrooksAL,PayneLE,Vaughn WK.Severefunctionaldeclines,workdisability,andincreased mortalityinseventy-fiverheumatoidarthritispatients studiedovernineyears.ArthritisRheum.1984;27: 864–72.

15.Avi ˜na-ZubietaJA,ChoiHK,SadatsafaviM,EtminanM,Esdaile JM,LacailleD.Riskofcardiovascularmortalityinpatients withrheumatoidarthritis:ameta-analysisofobservational studies.ArthritisRheum.2008;59:1690–7.

16.BlüherM.Adiposetissuedysfunctioninobesity.ExpClin EndocrinolDiabetes.2009;117:241–50.

17.VanGaalLF,MertensIL,DeBlockCE.Mechanismslinking obesitywithcardiovasculardisease.Nature.2006;444: 875–80.

18.AjeganovaS,AnderssonML,HafströmI,GroupBS. Associationofobesitywithworsediseaseseverityin rheumatoidarthritisaswellaswithcomorbidities:a long-termfollowupfromdiseaseonset.ArthritisCareRes (Hoboken).2013;65:78–87.

19.WolfeF,MichaudK.Effectofbodymassindexonmortality andclinicalstatusinrheumatoidarthritis.ArthritisCareRes (Hoboken).2012;64:1471–9.

20.OnuoraS.Rheumatoidarthritis.HowbadisobesityforRA? NatRevRheumatol.2012;8:306.

21.GremeseE,CarlettoA,PadovanM,AtzeniF,RaffeinerB, GiardinaAR,etal.Obesityandreductionoftheresponserate toanti-tumornecrosisfactor␣inrheumatoidarthritis:an

approachtoapersonalizedmedicine.ArthritisCareRes (Hoboken).2013;65:94–100.

22.HeimansL,vandenBroekM,leCessieS,SiegerinkB,Riyazi N,HanKH,etal.Associationofhighbodymassindexwith decreasedtreatmentresponsetocombinationtherapyin recent-onsetrheumatoidarthritispatients.ArthritisCareRes (Hoboken).2013;65:1235–42.

23.Gómez-AmbrosiJ,SilvaC,GalofréJC,EscaladaJ,SantosS, MillánD,etal.Bodymassíndexclassificationmissessubjects withincreasedcardiometabolicriskfactorsrelatedto elevatedadiposity.IntJObes(London).2012;36:286–94. 24.KatzPP,YazdanyJ,TrupinL,SchmajukG,MargarettenM,

BartonJ,etal.Sexdifferencesinassessmentofobesityin rheumatoidarthritis.ArthritisCareRes(Hoboken). 2013;65:62–70.

25.DaoH-H.Abnormalbodycompositionphenotypesin Vietnamese’swomenwithearlyrheumatoidarthritis.In:Do Q-T,ed.Rheumatology,2011:1250–1258.

26.HunterHL,NagyTR.Bodycompositioninaseasonalmodelof obesity:longitudinalmeasuresandvalidationofDXA.Obes Res.2002;10:1180–7.

27.MazessRB,BardenHS,BisekJP,HansonJ.Dual-energyX-ray absorptiometryfortotal-bodyandregionalbone-mineraland soft-tissuecomposition.AmJClinNutr.1990;51:1106–12. 28.VisserM,PahorM,TylavskyF,KritchevskySB,CauleyJA,

NewmanAB,etal.One-andtwo-yearchangeinbody compositionasmeasuredbyDXAinapopulation-based cohortofoldermenandwomen.JApplPhysiol.1985 2003;94:2368–74.

29.WesthovensR,NijsJ,TaelmanV,DequekerJ.Body compositioninrheumatoidarthritis.BrJRheumatol. 1997;36:444–8.

30.GilesJT,LingSM,FerrucciL,BartlettSJ,AndersenRE,Towns M,etal.Abnormalbodycompositionphenotypesinolder rheumatoidarthritispatients:associationwithdisease characteristicsandpharmacotherapies.ArthritisRheum. 2008;59:807–15.

31.ArnettFC,EdworthySM,BlochDA,McShaneDJ,FriesJF, CooperNS,etal.TheAmericanRheumatismAssociation 1987revisedcriteriafortheclassificationofrheumatoid arthritis.ArthritisRheum.1988;31:315–24.

32.AletahaD,NeogiT,SilmanAJ,FunovitsJ,FelsonDT,Bingham CO3rd,etal.2010Rheumatoidarthritisclassificationcriteria: anAmericanCollegeofRheumatology/EuropeanLeague AgainstRheumatismcollaborativeinitiative.Arthritis Rheum.2010;62:2569–81.

33.Physicalstatus:theuseandinterpretationofanthropometry. ReportofaWHOExpertCommittee.WorldHealthOrganTech RepSer.1995;854:1–452.

34.AlbertiKG,ZimmetP,ShawJ.Metabolicsyndrome–anew world-widedefinition.AConsensusStatementfromthe InternationalDiabetesFederation.DiabetMed.

2006;23:469–80.

35.ValdezR.Asimplemodel-basedindexofabdominal adiposity.JClinEpidemiol.1991;44:955–6.

36.BrayG.Contemporarydiagnosisandmanagementofobesity andthemetabolicsyndrome.Newtown,PA:Handbooksin HealthCare;2003.

38.SingT,SanderO,BeerenwinkelN,LengauerT.ROCR: visualizingclassifierperformanceinR.Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3940–1.

39.KatzP,YazdanyJ,TrupinL,SchmajukG,MargarettenM, CriswellLA,etal.Genderdifferencesinassessmentofobesity inrheumatoidarthritis.ArthritisCareRes(Hoboken). 2013:62–70.

40.Obesity:preventingandmanagingtheglobalepidemic. ReportofaWHOconsultation.WorldHealthOrganTechRep Ser.2000;894,i–xii,1–253.

41.CardielMH,Pons-EstelBA,SacnunMP,WojdylaD,SauritV, MarcosJC,etal.Treatmentofearlyrheumatoidarthritisina multinationalinceptioncohortofLatinAmericanpatients: theGLADARexperience.JClinRheumatol.2012;18: 327–35.