www.jped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Association

between

postpartum

depression

and

the

practice

of

exclusive

breastfeeding

in

the

first

three

months

of

life

夽

,

夽夽

Catarine

S.

Silva

a,∗,

Marilia

C.

Lima

b,

Leopoldina

A.S.

Sequeira-de-Andrade

c,

Juliana

S.

Oliveira

a,

Jailma

S.

Monteiro

c,

Niedja

M.S.

Lima

d,

Rijane

M.A.B.

Santos

e,

Pedro

I.C.

Lira

caCentroAcadêmicodeVitória,UniversidadeFederaldePernambuco(UFPE),NúcleodeNutric¸ão,VitóriadeSantoAntão,PE,

Brazil

bUniversidadeFederaldePernambuco(UFPE),DepartamentoMaternoInfantil,Recife,PE,Brazil cUniversidadeFederaldePernambuco(UFPE),DepartamentodeNutric¸ão,Recife,PE,Brazil

dCentroAcadêmicodeVitória,UniversidadeFederaldePernambuco(UFPE),VitóriadeSantoAntão,PE,Brazil eSecretariadeSaúdedePernambuco,Recife,PE,Brazil

Received4December2015;accepted9August2016 Availableonline26December2016

KEYWORDS

Breastfeeding; Postpartum depression; Weaning; Infants; Childcare; Antenatalcare

Abstract

Objective: Toinvestigatetheassociationbetweenpostpartumdepressionandtheoccurrence

ofexclusivebreastfeeding.

Method: Thisisacross-sectionalstudyconductedinthestatesoftheNortheastregion,

dur-ingthevaccinationcampaignin2010.Thesampleconsistedof2583mother---childpairs,with childrenagedfrom15daysto3months.TheEdinburghPostnatalDepressionScalewasusedto screenforpostpartumdepression.Theoutcomewaslackofexclusivebreastfeeding,definedas theoccurrenceofthispracticeinthe24hprecedingtheinterview.Postpartumdepressionwas theexplanatoryvariableofinterestandthecovariateswere:socioeconomicanddemographic conditions;maternalhealthcare;prenatal,delivery,andpostnatalcare;andthechild’s bio-logicalfactors.Multivariatelogisticregressionanalysiswasconductedtocontrolforpossible confoundingfactors.

Results: Exclusivebreastfeeding was observedin 50.8%ofthe infantsand 11.8%ofwomen

had symptomsof postpartum depression. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis,a higherchanceofexclusivebreastfeedingabsencewasfoundamongmotherswithsymptomsof

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:SilvaCS,LimaMC,Sequeira-de-AndradeLA,OliveiraJS,MonteiroJS,LimaNM,etal.Associationbetween postpartumdepressionandthepracticeofexclusivebreastfeedinginthefirstthreemonthsoflife.JPediatr(RioJ).2017;93:356---64.

夽夽

StudyconductedatUniversidadeFederaldePernambuco,Pós-graduac¸ãoemSaúdedaCrianc¸aedoAdolescente,Recife,PE,Brazil. ∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:catarine.nutri@yahoo.com.br(C.S.Silva).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2016.08.005

postpartum depression(OR=1.67;p<0.001),among younger subjects (OR=1.89; p<0.001), thosewhoreportedreceivingbenefitsfromtheBolsaFamília Program(OR=1.25;p=0.016), andthosestartedantenatalcarelaterduringpregnancy(OR=2.14;p=0.032).

Conclusions: Postpartumdepressioncontributedtoreducingthepracticeofexclusive

breast-feeding. Therefore, thisdisorder shouldbe included inthe prenatal and earlypostpartum supportguidelinesforbreastfeeding,especiallyinlowsocioeconomicstatuswomen.

©2016PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.onbehalfofSociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.Thisis anopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Aleitamentomaterno; Depressãopós-parto; Desmameprecoce; Lactentes;

Cuidadodacrianc¸a; Assistênciapré-natal

Associac¸ãoentreadepressãopós-partoeapráticadoaleitamentomaternoexclusivo

nostrêsprimeirosmesesdevida

Resumo

Objetivo: Verificar aassociac¸ão entreadepressãopós-partoe aocorrênciadoaleitamento

maternoexclusivo.

Método: EstudodecortetransversalrealizadonosestadosdaregiãoNordeste,durantea

cam-panhadevacinac¸ãode2010.Aamostraconsistiude2583binômiosmães-crianc¸ascomidade entre15diase3meses.Utilizou-seaEscaladeDepressãoPós-PartodeEdimburgopararastrear adepressãopós-parto.Odesfechoconsistiudaausênciadealeitamentomaternoexclusivonas 24 horasqueantecederam aentrevista. Adepressão pós-partofoi variávelexplanatória de interesse eas covariáveisforam: as condic¸ões socioeconômicas edemográficas, assistência pré-natal,aopartoepós-natal,efatoresdacrianc¸a.Realizou-seanálisederegressãologística multivariadacomoobjetivodecontrolarpossíveisfatoresdeconfusão.

Resultados: Aamamentac¸ãoexclusivafoiobservadaem50,8%dascrianc¸ase11,8%das

mul-heresapresentaramsintomatologiaindicativadedepressãopós-parto.Naanálisederegressão logística multivariadafoiverificadauma maiorchance deausênciadoaleitamentomaterno exclusivoentreasmãescomsintomasdedepressãopós-parto(OR=1,67;p<0,001).

Conclusões: Adepressãopós-partocontribuiuparareduc¸ãodapráticadoaleitamentomaterno

exclusivo.Assimsendo,essetranstornodeveriaserincluídonasorientac¸õesdesuportedesdeo pré-natalenosprimeirosmesespós-parto,especialmente,emmulheresdebaixonível socioe-conômico.

©2016PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.emnomedeSociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.Este ´

eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Thebenefitsofbreastfeedingformaternalandchildhealth arewell-established in the scientific literature. Consider-ing its importance,the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendsthepracticeofexclusivematernal breastfeed-ingduringthefirstsixmonthsoflife,andafterthisperiod, the introduction of adequate and healthy complementary feeding together with the maintenance of breastfeeding for up to two years or more.1 Despite the well-known advantagesofexclusivebreastfeeding(EBF),Brazilstilllags behind incomplying withthis recommendation. Inrecent years, there has been an increase in the prevalence of breastfeeding; however,the early termination of EBF can stillbeconsideredamajorpublichealthproblem.2

SeveralfactorshavebeenattributedtoearlyEBF inter-ruption, such as socioeconomic and cultural conditions, those relatedto age, maternal schooling,family income, early introduction of artificial nipples, and care factors, such as the number of prenatal consultations, hospital postpartum practice, rooming-in in the maternity ward, basic health care follow-up, and others related to the

conditionsofbirthandhealthofinfantsandthesocial sup-portnetwork.3

Recent studies have suggested an association between postpartumdepressionsymptoms(PPD)withtheearly inter-ruptionofEBF4andwithbreastfeeding(BF).5,6PPDisamood disorderthataffectswomenwithin4---6weeksofdelivery, reachingitsmaximumintensityinthefirstsixmonths,which maybeprolongeduntiltheendofthefirstpostpartumyear.7 Thereisahypothesisthatdepressedmothersareless confi-dentabouttheirabilitytobreastfeedandthereforewould belesswillingtocontinuebreastfeedingwhencomparedto thosewithoutdepressivesymptoms.4,8

There is noconsensusonthe association between PPD anddurationofbreastfeeding,sincesomestudieshavenot foundan association between thesetwofactors,9,10 while othersreportthat mothers withdepressivesymptoms are morevulnerabletoearlyinterruptionofBF,includingEBF, asthey couldhave greater difficulties and dissatisfaction withthispractice.4,8,11,12

from7.2%to39.4%.13,14Therefore,consideringtheneedto investigatetheassociationbetweenPPDandearly termina-tionofEBF,thisstudyaimstoverifytheassociationbetween maternalpostpartumdepressionandthepracticeofEBFin infantsyoungerthan3months.

Methods

Studysiteandpopulation

Thisstudyusesdatafromthesurvey‘‘Evaluationof prena-tal,birthcareandcareofinfantsunderoneyearoldinthe LegalAmazon andthe Northeastregions, Brazil,2010’’.13 Thepresentwasacross-sectionalstudycarriedoutinJune 12, 2010, during the child multi-vaccination campaign in ninestatesin theNortheastregionand eightin theLegal Amazonregion,in Brazil.The original study hadasa tar-get population mothers and children under 1 year, from theprioritymunicipalitiesaccordingtotheInfantMortality ReductionPlan.

The inclusion criteriaof the original study were: child aged less than 1 year, living in the same municipality of the vaccination unit where the study was performed, no twinsoradoptedchildren.Ifthemotherhadtwochildren under1yearofage,theyoungestchildwaschosenforthe study,aimingtominimizebiasinthemother’srecall.Forthe presentstudy,datafromtheNortheastregionwereusedand motherswithchildrenunder15dayswereexcludedaiming toavoid confounding the symptoms of PPD and the phe-nomenon known as ‘‘maternity blues’’ or ‘‘baby blues’’, acondition characterizedby symptomssuch asemotional labilityandfeelingsofsadnessandanxiety,oftenobserved inthefirsttwoweekspostpartum.14,15

Samplesizeandsamplingprocess

Samplesizecalculation fortheoriginalstudy13 considered an expected prevalence of 22% for ‘‘some complication duringbirth (self-reported),’’according todata fromthe 2006/2007NationalDemographicandHealthSurvey.16 The sampleplans werecreatedbasedoninformationprovided bytheStateHealthSecretariats,on:(A)numberof vaccina-tionunitsineachmunicipality;(B)estimateofthenumberof childrenunder1yearwhowouldbevaccinatedateachunit basedonthe2009vaccinationcampaignworksheets;(C)size oftheresidentpopulationunder1yearineachmunicipality. In the capitals, two-stage conglomerate sampling with drawingoflotswasused.Thesamplesizewasmultipliedby thedesigncorrectionfactor(deff=1.5),whichdetermined asampleof750motherandchildpairsforeachstate.Inthe firststage,thevaccinationunitswererandomlyselectedby drawinglots,andfor thesecond stage,alotfractionwas definedforeach unit,inordertocarryoutthesystematic selection in the vaccination line. The sample, for all the capitals,wasself-weighted,i.e.,allwereequallylikelyto beselected.13

Inrelation tothecountrysideofeach state, all munic-ipalitiesthatparticipatedintheresearchwereconsidered asstrata, andthe setof municipalities inthecountryside ofeachstatecomprisedasamplingdomain.Ineach munic-ipality,onetosixvaccinationunitswererandomlyselected

bydrawinglots,dependingonthepopulationofthe munic-ipalityandthenumberofexistingvaccinationunits.13

The systematic selection of the interviewed mother---child pair sought to obey the interval deter-minedinthesamplingprocess,accordingtothelotfraction foreachvaccinationunit.However,inanattempttoadjust theintervaltotheday’sdemand,thisintervalwasreduced at the beginning of the fieldwork, when a low demand for vaccinationwasobserved onthatday, considering the inclusionandselectioncriteria.13

The sample for the present study consisted of 2583 mother---childpairs,withchildrenagedbetween15daysand 3monthsofage.Atotalof324casesdidnotanswerthe ques-tionnaire,andthus,thesampleforthePPDvariableresulted in2259mother---childpairs.

Studyvariables

TheexplanatoryvariablewasPPDandthecovariateswere: maternalsocioeconomicanddemographicconditions[age, schooling, Bolsa Família Program (BFP) beneficiary (Fed-eral government’s program to guarantee food and access toeducationandhealth for low-incomefamilies)], prena-talcare(prenatalcareassistance,numberofconsultations, prenatalcare start trimester, havingreceivedinformation onBF,breastexaminationduringprenatalcare,and prena-talevaluationbythepregnantwoman);birthcare(typeof maternity,typeofdelivery,presenceofcompanion during delivery);postnatalcare(breastfeedinginthefirsthourof life,presenceofcompanionandrooming-inafterdelivery, seeking health care service in the first week postpartum, homevisitsbyafamilyhealthprofessionalafterchildbirth, currenthomevisitsbyacommunityhealthagentoranother familyhealthprofessional);child-relatedvariables(gender, birthweight,hospitalizationinthefirstmonthoflifeafter dischargefromthematernityward).Theoutcomevariable wastheabsenceoftheEBFpracticeinthe24hpriortothe interview.

Maternalbreastfeedingdefinition

ToclassifythebreastfeedingprofileasEBF,theWorldHealth Organization’sdefinitionwasused:thechild must receive onlybreastmilk,andnootherliquidsor solids,exceptfor dropsorliquidpreparationscontainingvitamins,oral rehy-drationsolutions,mineralsupplements,ormedications.1To classifythechildasinEBF,apositiveresponsewas consid-eredwhenbreastmilkconsumptionoccurredinthelast24h prior tothe interview andnegative for all other inquired foods.

Postpartumdepressionassessment

andintensityofthedepressivesymptom. Inthisstudy the scale was appliedthrough an interview. A score ≥12 was

usedasthecutoffpointforPPD,consideringthegood pre-dictivevalueshownbyvalidationstudiesandthepossibility ofbettercomparabilitywiththestudiescarriedoutinthe regionthatalsousedthesamecutoff.20,21

Datacollection

Aformwithclosedandpre-codedquestionsabout sociode-mographiccharacteristicsofthefamily;prenatal,birth,and postpartumcare;symptomsofpostpartumdepression;and dataonthechild’shealthwasusedfordatacollection.The interviewwascarriedoutafterthevaccination,inaroom reservedforthispurposeattheBasicHealthUnit(Unidade Básica de Saúde [UBS]), only with the mothers and chil-drenwhomettheinclusioncriteria. Inthecapitals,home visits weremade whenchildren under3monthswere not accompaniedbythemotherontheday ofthevaccination campaign,inordertoapplytheEPDStothemother,thereby performinganactivesearchforpossiblecasesofPPD.

Analysisplan

ThedatabaseanalysisusedSPSS,version13.0(SPSSfor Win-dows, Version 13.0, USA). The associations between the

variableswereexpressedthroughoddsratios(OR)andtheir respective95%confidenceintervals(95%CI),definingasthe referencecategorytheonethattheoreticallyhadahigher chanceofthemothertobeexclusivelybreastfeeding. Pear-son’schi-squaredtestwasusedtoevaluatetheassociation betweencategoricalvariables,withstatisticalsignificance setatp<0.05.

Aiming to control for possible confounding factors, a multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed, and variables withp<0.20 in the bivariate analysis were selectedforthisanalysis.FortheORadjustments,the hier-archical input approach of variables in blocks was used, inthreelevelsof determination,usingtheEnter method. Onlythe variables that showeda p-value <0.20remained inthemodels.Model1includedsocioeconomicand mater-naldemographicvariables.Model2includedthoserelated toprenatal care,while Model3 includedthoserelated to postnatalcare,thechild’svariables,andtheoccurrenceof PPD.

Ethicalaspects

TheprojectwasapprovedbytheResearchEthics Commit-teeoftheNationalSchoolofPublicHealth(ENSP/FIOCRUZ), incompliancewith ResolutionNo. 196/96of the National HealthCouncil,withresearchprotocolNo.56/10andCAAE No.0058.0.031.000-10.

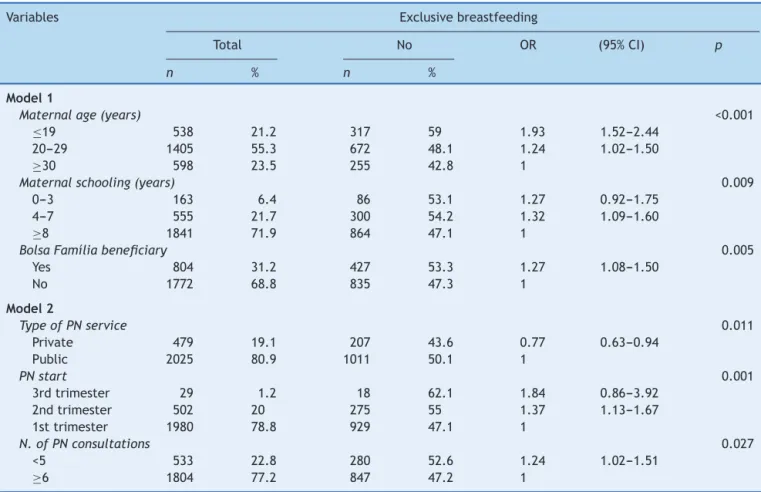

Table1 Socioeconomicstatusandprenatalcareinrelationtotheabsenceofexclusive breastfeedinginchildren under3 months.NortheasternRegion,2010.

Variables Exclusivebreastfeeding

Total No OR (95%CI) p

n % n %

Model1

Maternalage(years) <0.001

≤19 538 21.2 317 59 1.93 1.52---2.44

20---29 1405 55.3 672 48.1 1.24 1.02---1.50

≥30 598 23.5 255 42.8 1

Maternalschooling(years) 0.009

0---3 163 6.4 86 53.1 1.27 0.92---1.75

4---7 555 21.7 300 54.2 1.32 1.09---1.60

≥8 1841 71.9 864 47.1 1

BolsaFamíliabeneficiary 0.005

Yes 804 31.2 427 53.3 1.27 1.08---1.50

No 1772 68.8 835 47.3 1

Model2

TypeofPNservice 0.011

Private 479 19.1 207 43.6 0.77 0.63---0.94

Public 2025 80.9 1011 50.1 1

PNstart 0.001

3rdtrimester 29 1.2 18 62.1 1.84 0.86---3.92

2ndtrimester 502 20 275 55 1.37 1.13---1.67

1sttrimester 1980 78.8 929 47.1 1

N.ofPNconsultations 0.027

<5 533 22.8 280 52.6 1.24 1.02---1.51

≥6 1804 77.2 847 47.2 1

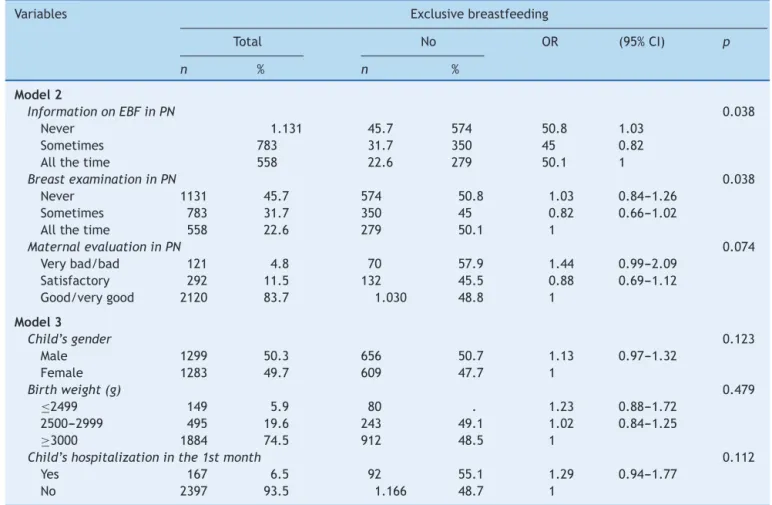

Table2 Prenatalcareandchildvariablesinrelationtotheabsenceofexclusivebreastfeedinginchildrenunder3months. Northeastregion,2010.

Variables Exclusivebreastfeeding

Total No OR (95%CI) p

n % n %

Model2

InformationonEBFinPN 0.038

Never 1.131 45.7 574 50.8 1.03

Sometimes 783 31.7 350 45 0.82

Allthetime 558 22.6 279 50.1 1

BreastexaminationinPN 0.038

Never 1131 45.7 574 50.8 1.03 0.84---1.26

Sometimes 783 31.7 350 45 0.82 0.66---1.02

Allthetime 558 22.6 279 50.1 1

MaternalevaluationinPN 0.074

Verybad/bad 121 4.8 70 57.9 1.44 0.99---2.09

Satisfactory 292 11.5 132 45.5 0.88 0.69---1.12

Good/verygood 2120 83.7 1.030 48.8 1

Model3

Child’sgender 0.123

Male 1299 50.3 656 50.7 1.13 0.97---1.32

Female 1283 49.7 609 47.7 1

Birthweight(g) 0.479

≤2499 149 5.9 80 . 1.23 0.88---1.72

2500---2999 495 19.6 243 49.1 1.02 0.84---1.25

≥3000 1884 74.5 912 48.5 1

Child’shospitalizationinthe1stmonth 0.112

Yes 167 6.5 92 55.1 1.29 0.94---1.77

No 2397 93.5 1.166 48.7 1

OR,oddsratio;CI,confidenceinterval;EBF,exclusivebreastfeeding;PN,prenatal.

Beforethequestionnairewasapplied,themotherswho agreedtoparticipateinthisstudysignedtheinformed con-sent form and were made aware that the confidentiality andprivacyoftheinformationprovidedwasassured.When symptomssuggestiveofpostpartumdepressionwere iden-tified,themotherswerereferredtothePsychosocialCare Centers(CentrosdeAtendimentoPsicossocial[CAPS]).

Results

Thesampleconsistedof2583mother---childpairs,with chil-drenagedbetween15daysand3monthsoflife,ofwhom 2259 (87.5%) answered the questionnaire about maternal mentalhealth.Among these,approximately12%hadPPD. Mostmotherswereagedbetween20and29years(55.3%) and hadeight or more yearsof education (71.9%). 41.5% ofthechildren werein theage groupbetween31 and60 days,5.9%hadlowbirthweight,and50.8%hadadiet con-sistingexclusivelyofbreastmilk.Regardinghealthcare,it wasobserved that98.7% receivedprenatalcare, 80.9%of whichwasinthepublichealthcarenetwork.Ofthese,78.8% startedtoreceivedhealthcareinthefirsttrimesterofthe pregnancyand77.2%hadatleastsixprenatalconsultations.

Tables 1---3 show the bivariate analyses; variables with

p<0.20wereselectedforthelogisticregressionanalysis.

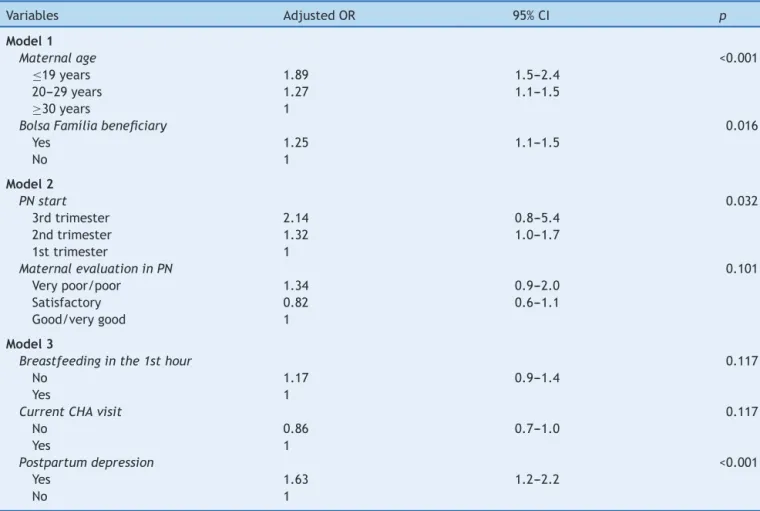

Table 4 shows, after adjustment in the multivariate logisticregressionanalysis,asignificantlyhigherchanceof absence of EBF among children whose mothers had PPD (OR=1.63),wereadolescents(OR=1.89),startedprenatal carelaterduringpregnancy(OR=2.14),orwereBFP bene-ficiaries(OR=1.25).

Discussion

This study showed aprevalence of approximately 12%for PPDinmotherswithchildrenagedbetween15daysand3 months.Studies carriedout inBrazil onthissubjecthave shown verywide-ranging estimates, varying from 7.2% to 39.4%.14,22Thisdisparityinresultscanbeattributedtothe useofdifferentmethodologicalstrategies,suchasdifferent studydesignsanddifferenttoolsforscreeninganddiagnosis, aswellasthetimingofthepostpartuminterview.6,11

AstudycarriedoutinRecife(PE),withasampleof276 postpartum women between the4th and6th weeks post-partum,whichusedtheEPDS asa screeningtoolandalso consideredascutoffascore≥12,foundaprevalenceofPPD

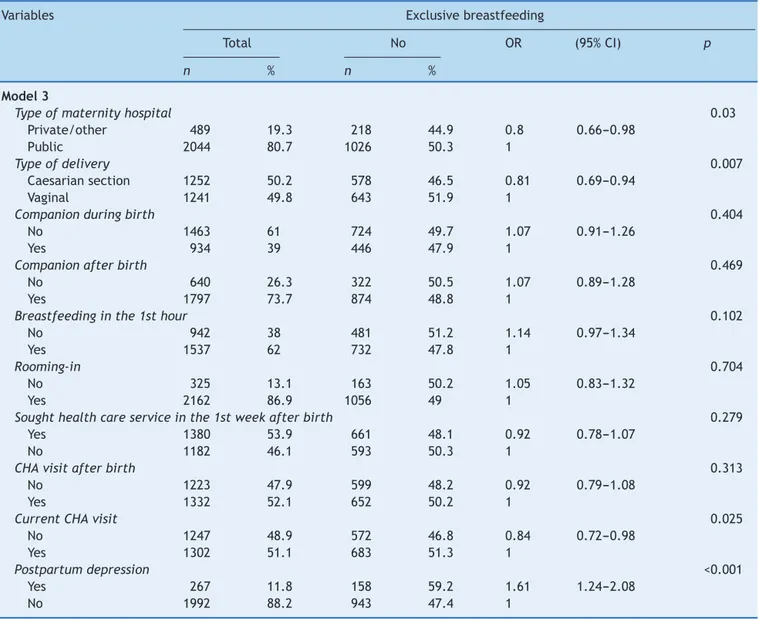

Table3 Birth,postnatalcare,andmaternalmentalhealthinrelationtotheabsenceofexclusivebreastfeedinginchildren under3months.Northeastregion,2010.

Variables Exclusivebreastfeeding

Total No OR (95%CI) p

n % n %

Model3

Typeofmaternityhospital 0.03

Private/other 489 19.3 218 44.9 0.8 0.66---0.98

Public 2044 80.7 1026 50.3 1

Typeofdelivery 0.007

Caesariansection 1252 50.2 578 46.5 0.81 0.69---0.94

Vaginal 1241 49.8 643 51.9 1

Companionduringbirth 0.404

No 1463 61 724 49.7 1.07 0.91---1.26

Yes 934 39 446 47.9 1

Companionafterbirth 0.469

No 640 26.3 322 50.5 1.07 0.89---1.28

Yes 1797 73.7 874 48.8 1

Breastfeedinginthe1sthour 0.102

No 942 38 481 51.2 1.14 0.97---1.34

Yes 1537 62 732 47.8 1

Rooming-in 0.704

No 325 13.1 163 50.2 1.05 0.83---1.32

Yes 2162 86.9 1056 49 1

Soughthealthcareserviceinthe1stweekafterbirth 0.279

Yes 1380 53.9 661 48.1 0.92 0.78---1.07

No 1182 46.1 593 50.3 1

CHAvisitafterbirth 0.313

No 1223 47.9 599 48.2 0.92 0.79---1.08

Yes 1332 52.1 652 50.2 1

CurrentCHAvisit 0.025

No 1247 48.9 572 46.8 0.84 0.72---0.98

Yes 1302 51.1 683 51.3 1

Postpartumdepression <0.001

Yes 267 11.8 158 59.2 1.61 1.24---2.08

No 1992 88.2 943 47.4 1

OR,oddsratio;CI,confidenceinterval;CHA,communityhealthagent.

due,amongotherfactors,tothedifferentmomentsatwhich thesurveyswerecarriedout,thedifferentcut-offpointsof thescreeningtool,andthemethodusedforsample selec-tion.

The presentstudyshowedthatmotherswithsymptoms suggestiveofPPDhada1.63-foldhigherchanceofEBF inter-ruption.Thisresultindicatestheimportanceofinvestigating maternalmentalhealthasoneofthepossibledeterminants ofearlyweaning.

TheassociationbetweenPPDandthepracticeofEBFis notyetwell-establishedintheliterature;however,thisissue hasbeenthesubjectofseveralscientificstudies,sinceone of theconsequences of PPD maybe thereduction of EBF duration.6 Despitethis observation, thereis noconsensus yet,assomestudiesindicatethatmotherswithdepressive symptomsaremorelikelytoabandonthepracticeofEBF,4,8 whereasothershavenotfoundanassociationbetweenthese factors.9,10

Theresultfoundinthisstudyisinagreementwiththat obtainedbyHasselmannetal.8whenevaluatingthe associ-ationbetweenPPDandearlyinterruptionofEBFinthefirst twomonthsoflife,usingEPDS score≥12asthescreening

method.Theseauthorsfoundthatchildrenofmotherswith depressivesymptomswereatahigherriskforEBF interrup-tion,bothinthefirstmonth(RR=1.46,p=0.06)andinthe secondmonthoffollow-up(RR=1.21;p=0.03),evenafter thesevariables werecontrolled for potential confounding factors.

Table4 Logisticregressionoffactorsassociated withtheabsenceofexclusive breastfeedinginchildren under3months. Northeastregion,2010.

Variables AdjustedOR 95%CI p

Model1

Maternalage <0.001

≤19years 1.89 1.5---2.4

20---29years 1.27 1.1---1.5

≥30years 1

BolsaFamíliabeneficiary 0.016

Yes 1.25 1.1---1.5

No 1

Model2

PNstart 0.032

3rdtrimester 2.14 0.8---5.4

2ndtrimester 1.32 1.0---1.7

1sttrimester 1

MaternalevaluationinPN 0.101

Verypoor/poor 1.34 0.9---2.0

Satisfactory 0.82 0.6---1.1

Good/verygood 1

Model3

Breastfeedinginthe1sthour 0.117

No 1.17 0.9---1.4

Yes 1

CurrentCHAvisit 0.117

No 0.86 0.7---1.0

Yes 1

Postpartumdepression <0.001

Yes 1.63 1.2---2.2

No 1

OR,oddsratio;CI,confidenceinterval;PN,prenatal;CHA,communityhealthagent. Model1:adjustedformaternalschooling.

Model2:adjustedforthevariablesofModel1andthevariables:prenatalservicetype,numberofprenatalconsultations,prenatal breastexamination,andinformationonbreastfeedingintheprenatalcare.

Model3:adjustedforthevariablesinModels1and2andthevariables:genderofthechild,hospitalizationinthefirstmonth,typeof delivery,andtypeofmaternityhospital.

which is demonstrated by maternal confidence in breast-feeding,tendstobeaffectedbydepressivesymptoms.4In theliterature,thereisahigherprobabilitythatwomenwith highself-esteeminthepostpartumperiodwillremainlonger inEBF.24

Thisstudy alsoobservedagreater trendofEBF discon-tinuationinyoungerwomen.Adolescents(≤19years)hada

1.89-foldhigherchanceofearly interruptionofEBF, while womenagedbetween20and29yearsshoweda 1.27-fold higherchancewhencomparedtothoseaged≥30years.

Sev-eralstudieshave confirmedthese results,astheysuggest thatmaternalagemaybeassociatedwiththeinterruption ofEBF,sothattheyoungerthemother,thegreatertherisk forearlyweaning.3,25 Thisfindingcanbeexplainedbythe greaterexperienceandknowledgeaboutbreastfeedingthat olderwomenhave,bythepossibleinsecurityofadolescents regardingtheirabilitytobreastfeed,26andalsobecausethey aremorepronetofeedingerrors,whichmayberelatedto thelowersocioeconomicstatusorrepetitiveeatinghabits, whichinmanycasesareinadequate.27

Studies have associated higherper capita incomeas a protective factor for EBF.28,29 In the present study,it was observed that families who were BFP beneficiaries, i.e., thosewithlowerpercapitafamilyincome,weremorelikely to interrupt EBF early (OR=1.25, p=0.016), showing the importanceofinvestigatinglow socioeconomicstatusasa riskfactorforearlyweaning.

In additiontothesocioeconomicanddemographic fac-tors,thereis alsotheinfluencehealthcare-related issues, specifically in the prenatal period. This study showed a greaterchanceofearlyinterruptionofEBFinmotherswho startedprenatalcarelaterduringthepregnancy.Thisresult wasinagreementwiththatobservedbyOliveiraetal.,2ina studycarriedoutinacityinthesemi-aridregionofParaíba, wherealongermediandurationofexclusive/predominant breastfeedingwasfoundamongwomenwhostarted prena-talcareearlierduringpregnancy.

Studieshaveshownthatinformationofferedduring pre-natalcarecontributetothedecisionofwomentopractice BFaswellastoitsduration,probablybecauseprenatalcare isafavorablemomentforeducationalinterventionsaimed atguidingandencouragingthepracticeofbreastfeeding.2,31 Thepresentstudywascarriedoutinstrategicregionsfor policies aimed toreduce health inequities, especially for thematernal---childgroup,byprovidingamulti-vaccination campaign,whichmadeitpossibletoassessarepresentative sampleofthepopulation,inadditiontoprioritizingrelevant aspectsofhealthcareandnutritionofinfants.Considering that this is a cross-sectional study, some aspects, due to theircomplexity,couldbeobtainedwithgreaterreliability inaprospectivefollow-up.

The findings of thisstudy reinforcethat thegenesis of earlyEBFinterruptioncanbecharacterizedas multifacto-rial,as thereisa complexinter-relationship between the economic,cultural,healthcare,andsocialsupport dimen-sions involved in the explanatory model of EBF duration. Consideringtheanalyzedaspects,amongtheseveral asso-ciated factors, the authors emphasize the importance of conducting studies that investigate the influence of men-talhealthinpostpartumwomen,duetotheconsequences onthemother---infantinteraction23 andonthe practiceof EBF,in ordertosupportactionsthatwillpromoteintegral attentiontomaternalandchildhealth.

Funding

Brazilian Ministry of Health,Secretariat of Science, Tech-nology, and Strategic Inputs, Department of Science and Technology.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

Theauthorswould liketothanktheMinistryofHealthfor fundingtheresearchandthedatabaseavailability,the par-ticipating women, the fieldwork team, and the research coordinators. They also thank the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the researchproductivitygranttoMariliaLimaandPedroLira.

References

1.World Health Organization (WHO). Indicators for assessing infantandyoungchildfeedingpractices.Geneva:WHO;2008.

2.OliveiraMG,LiraPI,BatistaFilhoM,LimaMdeC.Factors asso-ciatedwithbreastfeedingintwomunicipalitieswithlowhuman development index in Northeast Brazil.Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2013;16:178---89.

3.BoccoliniCS,CarvalhoML,OliveiraMI.Factorsassociatedwith exclusivebreastfeedinginthefirstsixmonthsoflifeinBrazil: asystematicreview.RevSaúdePública.2015;49:91.

4.Zubaran C,ForestiK.Thecorrelationbetweenbreastfeeding self-efficacyand maternalpostpartumdepressioninsouthern Brazil.SexReprodHealthc.2013;4:9---15.

5.Gaffney KF, Kitsantas P, Brito A, Swamidoss CS. Postpartum depression,infantfeedingpractices,andinfantweightgainat sixmonthsofage.JPediatrHealthCare.2014;28:43---50. 6.DennisCL,McQueenK.Therelationshipbetweeninfant-feeding

outcomesandpostpartumdepression:aqualitativesystematic review.Pediatrics.2009;123:e736---51.

7.SantosJuniorHP,RosaGualdaDM,deFátimaAraújoSilveiraM, HallWA.Postpartumdepression:the(in)experienceofBrazilian primaryhealthcareprofessionals.JAdvNurs.2013;69:1248---58. 8.HasselmannMH,WerneckGL,SilvaCV.Symptomsofpostpartum depression and early interruption of exclusive breastfeed-ing in the first two months of life. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24:S341---52.

9.AnnagürA, Annagür BB,S¸ahin A, ÖrsR, Kara F.Is maternal depressive symptomatologyeffective onsuccess ofexclusive breastfeeding during postpartum 6 weeks? Breastfeed Med. 2013;8:53---7.

10.McKeeMD,ZayasLH,JankowskiKR.Breastfeedingintentionand practiceinanurbanminoritypopulation:relationshipto mater-naldepressivesymptomsandmother---infantcloseness.JReprod InfantPsychol.2004;22:167---81.

11.DennisCL,McQueenK.Doesmaternal postpartumdepressive symptomatologyinfluenceinfantfeedingoutcomes?Acta Pae-diatr.2007;96:590---4.

12.Henderson JJ, Evans SF, Straton JA, Priest SR, Hagan R. Impact of postnatal depression on breastfeeding duration. Birth.2003;30:175---80.

13.Brasil.MinistériodaSaúde,SecretariadeCiência,Tecnologia eInsumosEstratégicos,DepartamentodeCiênciaeTecnologia. Avaliac¸ãodaatenc¸ãoaopré-natal,aopartoeaosmenoresde umanonaAmazôniaLegalenoNordeste,Brasil,2010.Brasília: MinistériodaSaúde;2013,136p.

14.CantilinoA,ZambaldiCF,AlbuquerqueTL,PaesJA, Montene-groAC,SougeyEB.PostpartumdepressioninRecife---Brazil: prevalenceandassociationwithbio-socio-demographicfactors. JBrasPsiquiatr.2010;59:1---9.

15.World Health Organization (WHO). Mental health aspects of women’sreproductivehealth:aglobalreviewoftheliterature. Geneva:WHO;2009.

16.Brasil.MinistériodaSaúde,CentroBrasileirodeAnálisee Plane-jamento.PesquisaNacionaldeDemografiaeSaúdedaCrianc¸a edaMulher---PNDS2006:dimensõesdoprocessoreprodutivoe dasaúdedacrianc¸a.Brasília:MinistériodaSaúde;2009,300p. 17.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Developmentofthe10-item Edinburgh Postnatal DepressionScale.BrJPsychiatry.1987;150:782---6.

18.ParsonsCE,YoungKS,RochatTJ,KringelbachML,SteinA. Post-nataldepressionanditseffectsonchilddevelopment:areview ofevidence from low-and middle-incomecountries. BrMed Bull.2012;101:57---79.

19.SantosIS, MatijasevichA, Tavares BF, BarrosAJ, Botelho IP, LapolliC,etal.ValidationoftheEdinburghPostnatal Depres-sionScale(EPDS)inasampleofmothersfromthe2004Pelotas BirthCohortStudy.CadSaudePublica.2007;23:2577---88. 20.MeloEF Jr,CecattiJG, PacagnellaRC, Leite DF,Vulcani DE,

21.LudermirAB,LewisG,ValongueiroSA,deAraújoTV,ArayaR. Violenceagainstwomenbytheirintimatepartnerduring preg-nancy and postnatal depression: a prospective cohort study. Lancet.2010;376:903---10.

22.RuschiGE, SunSY,Mattar R, ChambôFilho A, ZandonadeE, LimaVJ.Aspectosepidemiológicosdadepressãopós-partoem amostrabrasileira.RevPsiquiatrRioGdSul.2007;29:274---80. 23.Andrade GomesL, da SilvaTorquato V,Rodrigues Feitoza A,

RodriguesdeSouzaA,MonteirodaSilvaMA,SoaresPontesRJ. Identifyingtheriskfactorsforpostpartumdepression: impor-tanceofearlydiagnosis.RevRene.2010;11:117---23.

24.Morgado CM, Werneck GL, Hasselmann MH. Social network, socialsupportandfeedinghabitsofinfantsintheirfourthmonth oflife.CienSaudeColet.2013;18:367---76.

25.TarrantRC,YoungerKM,Sheridan-PereiraM,White MJ, Kear-ney JM. Factors associated with weaning practices in term infants:aprospectiveobservationalstudyinIreland.BrJNutr. 2010;104:1544---54.

26.Monteiro JC, Dias FA, Stefanello J, Reis MC, Nakano AM, Gomes-Sponholz FA. Breastfeeding among Brazilian adoles-cents:practiceandneeds.Midwifery.2014;30:359---63.

27.LimaAP,JavorskiM,VasconcelosMG.Eatinghabitsinthefirst yearoflife.RevBrasEnferm.2011;64:912---8.

28.Bittencourt LJ, Oliveira JS, Figueiroa JN, Batista Filho M. Aleitamentomaternono estado dePernambuco: prevalência epossível papeldasac¸õesdesaúde. RevBrasSaudeMatern Infant.2005;5:439---48.

29.Mascarenhas ML, Albernaz EP, Silva MB, Silveira RB. Preva-lence of exclusive breastfeeding and its determiners in the first3monthsoflifeintheSouthofBrazil.JPediatr(RioJ). 2006;82:289---94.

30.CarrascozaKC,PossobonRdeF,AmbrosanoGM,CostaJúnior AL, Moraes AB. Determinants of theexclusive breastfeeding abandonment in children assisted by interdisciplinary pro-gramonbreastfeedingpromotion.CienSaudeColet.2011;16: 4139---46.