REVISTA

BRASILEIRA

DE

ANESTESIOLOGIA

PublicaçãoOficialdaSociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologiawww.sba.com.br

SPECIAL

ARTICLE

Occupational

hazards,

DNA

damage,

and

oxidative

stress

on

exposure

to

waste

anesthetic

gases

Lorena

M.C.

Lucio,

Mariana

G.

Braz

∗,

Paulo

do

Nascimento

Junior,

José

Reinaldo

C.

Braz,

Leandro

G.

Braz

UniversidadeEstadualPaulista(Unesp),FaculdadedeMedicinadeBotucatu,DepartamentodeAnestesiologia,Botucatu,SP,Brazil

Received13December2016;accepted24May2017 Availableonline10August2017

KEYWORDS Inhaledanesthetics; Occupational exposure; Environment pollution;

Genotoxicitytesting; Genomicinstability; Oxidativestress

Abstract

Backgroundandobjectives: Thewasteanestheticgases(WAGs)presentintheambientairof operatingrooms(OR),areassociatedwithvariousoccupationalhazards.Thispaperintendsto discussoccupationalexposuretoWAGsanditsimpactonexposedprofessionals,withemphasis ongeneticdamageandoxidativestress.

Content: Despitetheemergenceofsaferinhaledanesthetics,occupationalexposuretoWAGs remainsacurrentconcern.Factorsrelatedtoanesthetictechniquesandanesthesia worksta-tions,inadditiontotheabsenceofascavenging systemintheOR,contributetoanesthetic pollution.Inordertominimizethehealthrisksofexposedprofessionals,severalcountrieshave recommendedlegislationwithmaximumexposurelimits.However,developingcountriesstill require measurementofWAGsandregulationforoccupationalexposuretoWAGs.WAGsare capableofinducingdamagetothegeneticmaterial,suchasDNAdamageassessedusingthe cometassayandincreasedfrequencyofmicronucleusinprofessionalswithlong-termexposure. OxidativestressisalsoassociatedwithWAGsexposure,asitinduceslipidperoxidation,oxidative damageinDNA,andimpairmentoftheantioxidantdefensesysteminexposedprofessionals.

Conclusions: Theoccupationalhazards relatedtoWAGsincludinggenotoxicity,mutagenicity and oxidativestress, standas apublichealth issueandmustbe acknowledgedby exposed personnelandresponsibleauthorities,especiallyindevelopingcountries.Thus,itisurgentto stablishmaximumsafelimitsofconcentrationofWAGsinORsandeducationalpracticesand protocolsforexposedprofessionals.

©2017SociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologia.Publishedby ElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisan openaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:mgbraz@hotmail.com(M.G.Braz). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2017.07.002

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Anestésicos

inalatórios; Exposic¸ão ocupacional; Poluic¸ãoambiental; Testesde

genotoxicidade; Instabilidade genômica; Estresseoxidativo

Riscosocupacionais,danosnomaterialgenéticoeestresseoxidativo frenteàexposic¸ãoaosresíduosdegasesanestésicos

Resumo

Justificativaeobjetivos: OsResíduosdeGasesAnestésicos(RGA)presentesnoarambientedas SalasdeOperac¸ão(SO)sãoassociadosariscosocupacionaisdiversos.Opresenteartigo propõe-seadiscorrersobreexposic¸ãoocupacionalaosRGAeseuimpactoemprofissionaisexpostos, comênfaseemdanosgenéticoseestresseoxidativo.

Conteúdo: Apesar do surgimento de anestésicosinalatórios mais seguros, a exposic¸ão ocu-pacionalaosRGA aindaépreocupac¸ãoatual.Fatoresrelacionadosàstécnicasanestésicase estac¸ãodeanestesia,alémdaausênciadesistemadeexaustãodegasesemSO,contribuempara poluic¸ãoanestésica.Paraminimizarosriscosàsaúdeemprofissionaisexpostos, recomendam-selimitesmáximosde exposic¸ão.Entretanto,em paísesem desenvolvimento,aindacarece amensurac¸ãodeRGAederegulamentac¸ãofrenteàexposic¸ãoocupacionalaosRGA.OsRGA sãocapazesdeinduzirdanosnomaterialgenético,comodanosnoDNAavaliadospelotestedo cometaeaumentonafrequênciademicronúcleosemprofissionaiscomexposic¸ãoprolongada.O estresseoxidativotambéméassociadoàexposic¸ãoaosRGAporinduzirlipoperoxidac¸ão,danos oxidativosnoDNAecomprometimentodosistemaantioxidanteemprofissionaisexpostos.

Conclusões:Portratar-sedequestãodesaúdepública,éimprescindívelreconhecerosriscos ocupacionaisrelacionadosaosRGA,inclusivegenotoxicidade,mutagenicidadeeestresse oxida-tivo.Urge anecessidadedemensurac¸ãodosRGA paraconhecimentodessesvalores nasSO, especialmenteempaísesem desenvolvimento,denormatizac¸ãodasconcentrac¸õesmáximas segurasdeRGAnasSO,alémdeseadotarempráticasdeeducac¸ãocomconscientizac¸ãodos profissionaisexpostos.

©2017SociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologia.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eum artigoOpen Accesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Wasteanestheticgases(WAGs)aresmallamountsofinhaled anestheticspresentmainlyintheoperatingroom(OR)and post-anesthesiacare unit(PACU)ambientair. Halogenated anesthetics, including halothane, isoflurane, sevoflurane, desflurane, and nitrous oxide (N2O) are the main

con-stituents of WAGs, as they are the most frequently used anesthetics.1

According to estimates by the American Occupational SafetyandHealthAdministration(OSHA),morethan200,000 healthprofessionalsareatriskofoccupationaldiseasesdue tochronicexposuretoWAGs.2Becauseitisapublichealth

issue,knowledgeoftheserisksandadoptionofformal prac-ticesandregulationstoreduceambientairpollutioninORs tosafeminimumlevelsofexposurearecritical.3Theaimof

thisarticleistoshowtheimpactsofoccupationalexposure toWAGsonexposedprofessionals’health,withemphasison topicsmorerecentlyexploredintheliterature,aswellas thedefinitionofgenotoxicity,mutagenicity, andoxidative stressappliedtoanesthesiology.

Background

Inhaledanestheticsaredrugswidelyandroutinelyusedin generalanesthesia. Theunprecedented public demonstra-tionofdiethyletherasaninhalationanestheticbyWilliam Morton in 1846 at the Massachusetts General Hospital in

BostonintheUnitedStatesenabledtoperformapain-free surgicalprocedureandgaverisetooneofthemost signifi-cantscientificdiscoveriesinmedicine.4

Sincethen,thepracticeofanesthesiologyhaswitnessed the profound evolution in this field, as other anesthetics emerged,suchasN2O,chloroform,andtrichloroethylene.

However,thehightoxicityandriskofexplosionwithinthe surgical environmentrelatedtotheseagentsdiscontinued its use andencouraged the search for safer anesthetics.5

In the 1950s, the first compound derived from fluoride ion (fluoroxene) was tested clinically, but wassoon ruled outasextremelytoxic.Halothane isahalogenated hydro-carbon synthesized in 1957, whose reduced flammability comparedtoagentsavailable at thattimeconsolidated it as the main inhaled anesthetic of the time, which lasts until today.6 In 1960, it was followed by methoxyflurane,

which had limited use due toits high nephrotoxicity.7 At

thesame time,reports ofrare casesofhalothane-related fatalhepatitisledtothesearchfornewerandsafervolatile anesthetics synthesized in the 1960s, such as enflurane in 1963 and its structural isomer isoflurane in 1965, in additiontosevofluraneanddesflurane(popularizedin the mid-1990s).7,8Xenon,recognizedasaninert,odorlessgas,

hasrapidabsorptionandeliminationthroughthelungs,no hepatic and renal metabolism, and minimal cardiovascu-lar effects. However, its use is still restricted due to its highcostandlimitedavailability.5Thus,theoptimalinhaled

Wasteanestheticgases(WAGs)

The surgical environment pollution with WAGs is essen-tiallyduetothreecauses:anesthetictechniques,anesthesia workstation,andORwithorwithoutascavengingsystem.9

Regardinganesthetictechniques,twomainfactorsmaybe enumerated:(1)induction and/ormaintenanceof general anesthesiawithinhaledanesthetics,particularlyinpediatric patientsviafacemask;(2)failuretoturnoffboththevalve thatcontrolstheflow(gasflowmeter)andvaporizer(when ORiswithoutpatient);(3)leakageofanestheticwhenfilling thevaporizer;(4)performingflushingattheendofsurgical proceduretoacceleraterecoveryfrominhalational anesthe-sia(commonandextremelyharmfulpractice);(5)problems withfacialmaskcoupling,eitherbymaterialthatis inappro-priateforuse,inadequatesizeorevenbydifficultiesrelated tothepatient’sairway;(6)leakageofgasafterinadequate endotrachealtube(ETT)cufforlaryngealmaskinflation,or bytheuseofuncuffedETT;(7)useofintermediatefreshgas flow(2---4L.min−1)andparticularlyhighflow(>4L.min−1)10;

(8)use of sidestreamtypecapnographwithnogas return totheanesthesiamachine;(9)useofMaplesonrespiratory system,particularlyinpediatricanesthesia.10,11

Regardinganesthesiaworkstation,numerouscomponents may be the reasonfor anesthetic leakage into the ambi-entair.Possibleleaksmaycomefromvalvesandrespiratory circuitconnections,defectsinpartsandreservoirbags.9,12

ORs may or may not have a scavenging system. When thereisascavengingsystem,itmaybeglobal(whenthereis centralsuctionthatdrawsairfromtheORthroughnegative pressure,ventingall theair withwaste gasesoutside the room, without air recirculation) or partial (when thereis centralsuctionthatdrawsairfromtheORthroughnegative pressure,partiallyventingtheairwithanestheticgastothe outside, withair recirculation).In OR withno scavenging system,thereisonlythenaturalcirculationofairflowfrom non-centralairconditioners.12

WAGenvironmentalrisks

WAGs eliminated from ORs to the external environment reachtheatmosphereunchangedandcauseenvironmental impact. The environmental damage caused by anesthetic gases depends on its molecular weight, proportion of halogenatoms,andhalf-lifeintheatmosphere.The approxi-mateatmospherichalf-lifeofanestheticgasesare:N2O:114

years;desflurane:10years;halothane:7years;sevoflurane: 5 years;and isoflurane: 3 years.13 All inhaled anesthetics

beingusedcontainhalogenatedcompounds thatresemble chlorofluorocarbons and thus have deleterious effects on theozonelayer.Besidesbeingoneofthedepletinggasesin theozonelayer,N2Oseizesthethermalradiationemanated

fromtheEarth’ssurfaceandcontributestothephenomenon ofglobalwarming,knownasthe‘‘greenhouseeffect’’.13

OccupationalhealthandWAGexposure

The possibility of health damage related to the inhaled anesthetic exposure has been the subject of debates in thelastdecades.14Severalprofessionals(anesthesiologists,

veterinarians and surgeons, nurses and related health

professionals, as well as students) active in ORs and/or PACUsarethepeoplemostexposedtoWAGs.1

Thefirststudythatdrewthescientificcommunity atten-tion to the risks associated with exposure to WAGs was conductedbyVa˘ısmanintheSovietUnionin1967.Itinvolved 198menand110womenanesthesiologistsexposed primar-ilytodiethylether,N2O,andhalothaneandfoundnotonly

symptoms such as fatigue, headache and irritability, but alsoshowed, for the first time,an adverse effect onthe reproductivesystem. Therewere18 casesof spontaneous abortion in 31 pregnancies in the group of female anes-thesiologists exposed toWAGs.15 This findingraised great

concernaboutthesafetyofexposedprofessionals.In1974, theAmericanSociety of Anesthesiologists (ASA)published intheUnitedStatesthestudyOccupationaldiseaseamong

operatingroompersonnel:anationalstudy.Reportofanad

hoccommitteeontheeffectofanestheticsonthehealthof

operatingroompersonnel.16Throughtheuseofa

question-naire,agroupof49,585professionalsexposedtoWAGswere comparedwith a group of 23,911 subjects without expo-sure.Inexposedwomen,anincreasedriskof spontaneous abortion,congenitalanomalies,cancer,andliverandkidney diseasewereseen.Maleanesthesiologists,however,hadan increasedriskof liverdiseaseandof havingchildren with congenitalabnormalities.16

Subsequently, these studies were reviewed by other authors, who found numerous methodological errors and biases(forexample,respondentbiasintheanalysisof ques-tionnaires and confoundingfactors, such as psychological stressandlongworkinghours).Thismainlyweakensthe evi-denceofthecausalassociationbetweenexposuretoinhaled anesthetics and negative reproductive outcomes (sponta-neousabortionandcongenitalabnormalities).14

LimitsofoccupationalexposuretoWAGs

Inviewoftheforegoing,therewasaneedfor formal rec-ommendationsto reduce occupational exposure toWAGs, especially the National Institute for Occupational Safety andHealth(NIOSH)in 197717 thatsuggested theadoption

of exposure limits to WAGs in any susceptible environ-mentusingtheseagents.OccupationalExposureLimitswere definedas: 2 partsper million (ppm)--- ceiling ---to halo-genatedagentsand25ppm---time-weightedaverage(TWA) --- to N2O during its administration time. Furdermore, it

wasrecommended the implementation of effective scav-engingsystemsthatallowanefficientairrenewalinORs.17

Thus,protocolsandtechnicalprocedureshave been insti-tutedintheUnitedStatestopreventanestheticgasleakage inOR, such ascarefulhandling of face mask, vaporizers, and flowmeters and tests to identify leaks in high and lowpressure systems. Surveillanceof exposed physicians’ healthstatuswithphysicalandlaboratoryexaminations,as needed,wasalsoaddressed, aswell astheneed to ambi-entairmonitoring todetermineWAGconcentrations, with documentationthroughreportsandserialinspections.17

N2O,50ppm for enflurane andisoflurane, and 10ppm for

halothane, because these values are much lower than those that cause adverse effects reported in experimen-tal studies.18 Other examples of nations with their own

legislationareFrance,Switzerland,Germany, Austria,the Netherlands,Italy,Sweden,Norway,Denmark,andPoland.14

In Brazil, the occupational exposure toWAGs is stilla subjectrarely exploredand lacksregulation by labor leg-islation.The maximum limitsofanesthetic gasesthat are safefortheworkerareabsent,aswellasrecommendations onmonitoringandinspection.The RegulatoryStandardNR 15(onunhealthyactivities andoperations) referstoN2O,

limitedonlyto‘‘asphyxiatingdoses’’.Inturn,NR32(health andsafetystandardatworkinhealthcareestablishments), althoughaddressingtheissuemoredirectlymentioningthe rightsofthepregnantworkerexposedtoWAGs,itdoes so inanunclearandinsufficientway.11

A national study conducted in the 1980s compared halothane concentrations in the air and blood of animals exposedtoexperimentalroom pollutionwithandwithout the Venturi system.19 The authors have shown the

effec-tivenessof thisanti-pollution system inexhausting WAGs. MostanesthesiologistsinBraziliansurgical centersusethe mostvariedtypesofinhaledanesthetics(fromhalothaneto desflurane)withoutprotocolsforreducingleakageand pol-lutioninORs,whichhavenoscavengingsystemtoeliminate WAGs.Itisworthnotingtheworkconductedinthe Depart-ment of Anesthesiology of the Botucatu Medical School (Unesp),which measured, for the firsttime, the environ-mental concentration of anesthetics in ORs of Brazilian surgical theaters, withhalf of the ORs withpartial scav-engingsystem,witha6---8airexchangear/handhalfofthe ORs without a scavengingsystem, with thelatter reflect-ingtherealityofmanyhospitalsindevelopingcountries.20

Themeanconcentrationofhalogenatedisoflurane, sevoflu-rane,anddesfluranewereabove5ppmandforN2Oitwas

higherthan170ppm(TWA).Accordingtotheinternational standardsadvocatedbytheAmericanInstituteofArchitects (1993),21atleast15airchangesperhourarerecommended

toensurethattheaircirculatinginORsiscompletelyfilled withfreshair.Moreover,theidealistouseaunidirectional orlaminarairflowsystem,whichallowsallthe contamina-tiongeneratedintheenvironmenttobetakenoutofitas soonaspossible.22

Thus,aqualitystandardisrequired,followedbyroutine inspectionsandregularmeasurementofWAGconcentrations inORtoascertaintheirproperfunctioning.Itisalsoworth notingthat thereis a smallnumber of studies addressing occupational exposure to WAGs and its possible deleteri-ouseffects in developing countries, suchasBrazil, which

makesitdifficulttoperceivethisimpactinthepopulation andhealthpersonnel.20,23---26

Theconcernwithoccupational exposure,regardingthe limitation of WAG concentrations, is a relevant issue due to the potential health risks of exposed professionals. It is well documented that such exposure, even for a shorttime, canbe reflectedin signs andsymptoms, such as headache, irritability, fatigue,nausea, dizziness, diffi-cultyjudgmentandcoordination.1 Moreseriouschangesin

exposedindividuals,includingkidneyandliverdamageand neurodegenerative conditions, suchas Parkinson’sdisease andproprioceptivechanges,havealsobeenreported.27,28

GenotoxicandmutagenicpotentialofWAGs

One of the important focuses of several studies is the potential of inhaled anesthetics to induce damage to geneticmaterial(genotoxicityandmutagenicity)evaluated in animals,29,30 patients,31---33 and occupationally exposed

professionals.20,34,35 Infact,geneticbiomarkershavebeen

widelyusedtomonitorhumanexposuretogenotoxicand/or mutagenic agents with potential carcinogenic effect.36

Amongthemajormarkersofgenotoxicityandmutagenicity arethecometandmicronucleus(MN)tests.

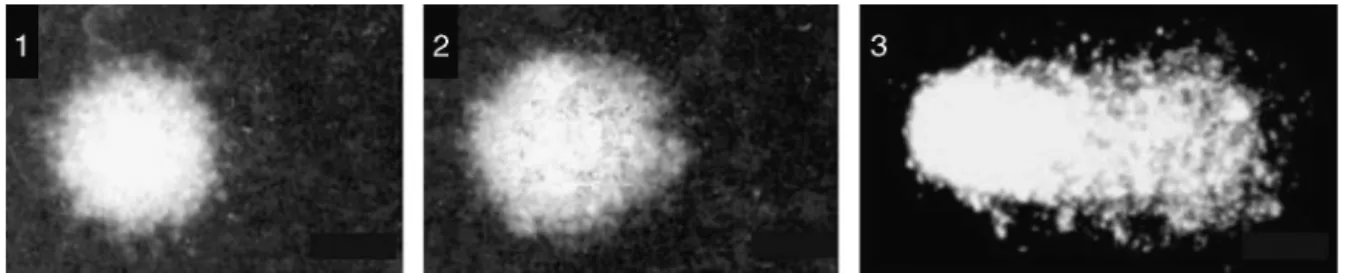

Thecomettestisasensitiveandcost-effectivemethod to measure DNA damage, which has been established as animportanttooltoevaluategenotoxicityinoccupational risk studies.37 Such methodology consistsof immersion of

eukaryotic cells in agarose gel, cell membrane lysis and subsequent electrophoresis. Under alkaline conditions of electrophoresis(pH>13),nucleoidswithDNAdamage(which have negativecharge) migrate tothepositive pole, mim-icking the appearance of a comet (head and tail). Thus, the fragmentsresultingfromsingle-and/or double-strand breaks of DNA, in addition to alkali-labile sites, migrate toward the anode of the electrophoresis trough.37 The

greater the presence of damaged genetic material, the greaterthemigrationoftheseDNAfragments.Thus,thetail extensionproportionallyreflectstheamountofDNAdamage (Fig.1).37

Althoughthegenotoxicityandmutagenicitymechanisms ofhalogenatedanestheticsarenotfullyelucidated,possible explanationsincludeoxidativemetabolismcapableof gen-eratingreactiveoxygenspecies(ROS)andtheinductionof directdamagetothegenomeatanystageofthecellcycle.23

On the other hand, N2O oxidizes the cobalt ion present

in cobalamin (vitamin B12), leading to the inhibition of methioninesynthetasewithreducedproductionof methio-nineandtetrahydrofolateanditsbyproductsthymidineand nucleic acids (includingDNA).38 Such changesare related

tomegaloblasticanemia,agranulocytosis,spinalcord suba-cutecombineddegeneration,andneurobehavioraldisorders inindividualsunderchronicexposureand/orelevated con-centrationsofN2O.38

In apioneeringstudyconducted inthenorthern region ofBrazil,25theeffectsofoccupationalexposuretoWAGson

geneticmaterialwereseen duringmedicalresidency.The authors found a significant increase of primary lesionsin theDNAofresidentphysiciansateight,16,and22months exposuretoisoflurane,sevoflurane, andN2Ocomparedto

acontrolgroup,inORswithnoscavengingsystem.On the other hand,therewasnoincreased basaldamagein lym-phocytesevaluatedinanesthesiologistschronicallyexposed toisoflurane,sevoflurane,desflurane,andN2Oinasurgical

centerwithpartialscavengingsystemofateachinghospital insoutheasternBrazil.20

The basalDNAdamage,detectedusingthecomettest, hasbeen evaluatedinthe population chronically exposed toWAGs,buttheresultsarecontroversial.35,39,40InTurkey,

forexample,therewasasignificantincreaseinlymphocyte DNAdamageof66professionals(anesthesiologists,nurses, andtechnicians)exposedtohalothane,isoflurane,andN2O

comparedtoacontrolgroup.39 Incontrast,aPolishstudy

showednodifferencein DNAdamagein 100 professionals exposedtoN2O,isoflurane,sevoflurane,andhalothane

com-paredtocontrolgrouporinterferencefromexposuretime intheoutcomes.35

There is evidence ofinteraction betweenfree radicals derived from oxygen or nitrogen with DNA bases, which resultsindamagesthatproduceoxidizedbases,abasicsites and/or DNA strand breaks. The comet test, traditionally usedtoassessbasalDNAdamage,canalsobemodifiedwith theuseofspecificenzymestoassessoxidationatDNAbases (pyrimidicandpurine).Thisapproachwasfoundinonlyone studyintheliterature,whichevaluatedoxidativeDNA dam-ageinnurseschronicallyexposedtoWAGs,andshowedan increaseinoxidizedpurines.41

MNsareextranuclearcorpusclesformedfromfragments ofchromosomesorwholechromosomesthatwereexcluded from the main nucleus of the daughter cell during cell division(Fig.2).Itsoccurrencerepresentsgenetic instabil-ityand impairment in cellularviabilitycaused by genetic defects or exogenous exposure to genotoxic/mutagenic agents.42 The association betweenMNdetected in

periph-eral lymphocytes and cancer has theoretical support. A cohort study conducted by the international HUman MicroNucleus (HUMN) projectfrom 1980to2002 involving 10countriesand6718individualsrelatedthefrequencyof MNinperipherallymphocytestoincreasedcancerriskina populationconsideredhealthy.43

AstudycomparingORsinGermanywithconcentrations below the recommended limitsof WAGs (with scavenging system) withother ORs withhigh concentrations of WAGs (withoutscavenging system)inan EasternEuropean coun-try,foundasignificantincrease ofMNinlymphocytesonly in professionals exposed to WAGsin ORs froman Eastern Europeanhospital.44InSlovenia,astudyshowedthatfemale

professionalsexposedtoisoflurane,halothane,andN2O(of

whichonlyisofluranewasabovetherecommended concen-tration limits in OR) had a significantly higher frequency ofMNandotherchromosomechangesinlymphocytesthan femaleradiologytechnologistsandcontrols.45

Figure2 Photomicrographyofbinucleatedcell(lymphocyte) containingonemicronucleus.

The use of MN in oral cells (evaluated by the Buccal MicronucleusCytomeAssay) is well established and inter-nationallyvalidatedandithasbeenwidelydisseminatedin thelastdecadebyhumanbiomonitoringstudiestoevaluate exposuretogenotoxicand/orcarcinogenicagents,aswellas neoplasticordegenerativediseases.Itsadvantagesinclude: (1)minimallyinvasivecollectionoforal mucosalcells;(2) high sensitivity;(3) specificity in detecting the effects of exposuretoinhaledoringestedgenotoxicagents;(4)ease storageofsamplesatroomtemperaturewithouttheneed for cell culture; and (5) low cost.46 The buccal MN assay

alsoallowstheevaluationofnuclearchangesanddifferent stagesofcelldifferentiationanddeath.47 Fig.3showsthe

oralmucosalayersandthedifferentcelltypesthatcanbe detectedinthemicronucleusbuccaltest.42 Thefrequency

ofMNintheexfoliatedoralcellshasapositivecorrelation withthatfoundinlymphocytes,showingthatthegenotoxic and/ormutagenic effectsseen in bloodstream,aswell as theirpotentialrisks(suchastheassociationwithcancer), are detected in buccal mucosa.48 In addition, exfoliated

cellsofbuccalmucosarepresentthefirstbiologicalbarrier ofcontactwithinhaledanesthetics.Intheliterature,there areonly tworeports ontheuseof buccalMN test in pro-fessionalschronicallyexposedtoWAGs.Thefirststudywas conductedinIndiaandasignificantincreaseinMNwasseen inseveralhealthprofessionals(surgeons,anesthesiologists, nurses,andtechnicians) exposedtohalothane,enflurane, isoflurane,sevoflurane,desflurane,andN2O.34 The second

study wasperformed in Botucatu, SP, Brazil, and showed thatanesthesiologistsexposedfor16years,onaverage,to the most modern WAGs have increased MN and cytotoxic alterations,aswell aschangesincellproliferationof oral mucosa.20

OxidativestressandWAGs

Horny layer

Spiny layer

Granular layer

Germ layer

Karyorrhectic cell

Chromatin-condensed cell

Pyknotic cell

Karyolytic cell Binucleated cell

Basal cell

MN basal cell

Differentiated cell

MN differentiated cell

Connective tissue

MBUD differentiated cell

Figure3 Schematicdepictingcutofbuccalmucosa,withitslayers,differentcelltypes,andchangesdetectedbymicronucleus test.MN,micronucleus;NBUD,nuclearbuds.

Source:FigureadaptedfromThomasetal.42

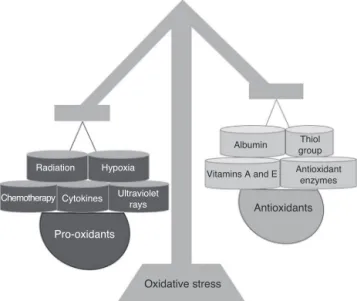

radicals are unstable molecules with unpaired electrons, which are extremely reactive. When these free radicals and other molecules arise as a result of oxidative reac-tions in biological systems, they are referred to as ROS, and can onset a cascade of reactions with biological molecules.49 Important examples of these reactions are

lipoperoxidationorlipidperoxidation,proteindamage,and oxidative damageto nucleicacids. The firstinvolves free

Albumin

Radiation Hypoxia

Cytokines Ultraviolet rays

Pro-oxidants Chemotherapy

Vitamins A and E Antioxidant enzymes

Antioxidants

Oxidative stress

Thiol group

Figure4 Representationofoxidativestressasanimbalance betweenpro-oxidantfactors(left)andantioxidants(right).

radical/ROS attack on membranes and lipoproteins and is implicated in the development of numerous diseases, such as atherosclerosis, cancer, and degenerative and inflammatory diseases.50 Protein damage occurs by the

formation of protein groups called carbonyls, which can induceproteolysisinDNAbases(oxidativeDNAdamage),as wellassingleanddoublestrandsbreaksingeneticmaterial (such as guanidine conversion into 8-hydroxyguanidine). Ultimately,freeradicalscanbetoxictotissuesor organs, with consequent cell damage, necrosis, and apoptosis.51

In fact, there is a relationship between genotoxicity and oxidativestress.52Oxidativestresscammainlyinduce

dam-agetomacromolecules,includingnucleicacids,lipids,and proteins,resultingincellulardamage,aswellasavarietyof diseases.51

Oxidativestresshasbeenstudiedusingseveral biomark-ers (Fig. 5). The use of protein oxidation byproducts (carbonylated proteins, S-glutathionation, and nitrotyro-sine),DNAoxidation(e.g.:8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosineor

8-OH-dG,phosphorylationofhistoneresiduesandincreased DNA migration using the comet test) and lipid peroxi-dation (malonaldehyde or MDA and 4-hydroxynonenal or 4-HNE, among others) is well known to determine the evaluationofoxidativestress.52 Fromanotherperspective,

oxidative stressmaybeevaluatedbyreducingantioxidant defenses,either bymeasuringenzymatic(e.g.:superoxide dismutase or SOD, glutathione peroxidase or GPX, cata-lase or CAT) or non-enzymatic antioxidant agents (e.g.: ascorbicacidorvitaminC,␣-tocopherolorvitaminE,

Membrane

Lipid peroxidation

(i) MDA ↑

(i) Carbonyl groups ↑

(i) Glycation end products ↑

(ii) Lipoxidation end products↑

(ii) S-Glutationylation ↑

(iii) Nitrosine ↑

Protein degradation products

(i) 8-OH-dG ↑

(ii) DNA migration (comet)↑

(ii) 4-HNE↑

Nucleous

Protein oxidation Oxidative

stress DNA strand breaks

Figure5 Biomarkersofmacromoleculeoxidativedamage.Oxidativestresscausesdamagetomacromolecules;forexample,DNA, lipids,andproteins.Thepresenceofoxidativestressinmacromoleculescanbedetectedthroughthebyproductsresultingfrom oxidation.MDA,malonaldehyde;4-HNE,4-hydroxynonenal;8-OH-dG,8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine.

Source:FigureadaptedfromLeeetal.52

A possible relationship between occupational exposure to WAGs and oxidative stress has been studied since last decade, but it is still a relatively unexplored field. A study conducted in ORs with no scavenging system showedincreasedlipidperoxidationbythiobarbituric acid-reactive-substancesandreducedantioxidantthiolgroupsin personnelexposedfornineyears,onaverage,tohalothane and N2O, but without change in the antioxidant capacity

test.53 Nurses working in ORs with noscavenging system,

exposedtoan average of 14.5yearsmainly toisoflurane, sevoflurane, desflurane, and N2O, had increased breaks

in genetic material and reduced enzyme and antioxidant capacitycomparedtothenon-exposedgroup.54Ontheother

hand, a study carriedout withTurkish personnel exposed toenflurane,halothane,isoflurane,sevoflurane,and desflu-raneinORswithpartialscavengingsystemshowedreduced plasmaGPX andSODantioxidantenzymesandcopper and seleniummicroelements,butwithincreasedzinccompared to controls.55 In personnel exposed to halothane,

isoflu-rane, sevoflurane, desflurane,and N2O, working for 3---11

years in surgical theater with scavenging system, there wasanegativecorrelationbetweengeneticmaterial dam-age and antioxidant capacity.56 In another study, when

comparing nurse exposed (5---27 years) to isoflurane and sevoflurane (low concentration)and N2O (high

concentra-tion)withacontrolgroup,it wasdetectedan increasein DNAbasesoxidativedamageandlipoperoxidationmarkers andreducedGPXantioxidantenzyme,butwithoutchanges in␣-tocopherolconcentrationinexposedpersonnel.41Thus,

moststudies showthat chronic exposuretoWAGsinduces bothoxidative damageanddecreased antioxidantdefense markers.41,53---56 In a research performed with physicians

during medical residency in anesthesiology and surgery (therefore, withshorter exposure time) exposedto WAGs in ORs with no scavenging system, there was increase in basal level of DNAdamage with changes in CAT and GPX enzymes,withnegative correlation betweenDNA damage andGPXantioxidantenzymecomparedtoacontrolgroup.25

Conclusion

Evidence has shown that prolonged/chronic occupational exposuretoWAGsmayinducedamagetogenomeandleadto oxidativestress.Thus,itisurgenttoimplementappropriate legislationinourcountry,aswellasindevelopingcountries, regarding the limit of occupational exposure to inhaled anesthetics.KnowledgeofanestheticmeasurementsinOR andSRPA isalso fundamental.It is alsoworth mentioning theneedfor furtherbiomonitoringstudies todetect early changes caused by WAGs in exposed personnel, favoring environmentinterventionbyimplantingeffective scaveng-ingsystemsinORsandindividualinterventionbyeducation andprotocolsthatensuretheuseofanesthetictechniques toreduceambientairpollution.

Financing

Fundac¸ão de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo(FAPESP), case no.2013/21130-0. L.M.C.L.received Sandwich Doctorate Scholarship from Coordenac¸ão de Aperfeic¸oamentodePessoaldeNívelSuperior(CAPES),case no.14527-13-8.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.NIOSH.Wasteanestheticgases:occupationalhazardsin hospi-tals.TheNationalInstituteforOccupationalSafetyandHealth ofTheUnitedStatesofAmerica;2007.

2.OSHA. Anestheticgases:guidelines forworkplace exposures. OccupationalSafetyandHealthAdministration;2000. 3.McgregorDG.Occupationalexposuretotraceconcentrationsof

4.WhalenFX,BaconDR,SmithHM.Inhaledanesthetics:an his-torical overview. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2005;19: 323---30.

5.CampagnaJA,MillerKW,FormanSA.Mechanismsofactionsof inhaledanesthetics.NEnglJMed.2003;348:2110---24. 6.Moppett I. Inhalational anaesthetics.Anaesth Intensive Care

Med.2012;13:348---53.

7.TorriG.Inhalationanesthetics:a review.MinervaAnestesiol. 2010;76:215---28.

8.UrbanBW,BleckwennM.Conceptsandcorrelationsrelevantto generalanaesthesia.BrJAnaesth.2002;89:3---16.

9.Yasny JS, White J. Environmental implicationsof anesthetic gases.AnesthProg.2012;59:154---8.

10.BakerAB.Lowflowandclosedcircuits.AnaesthIntensiveCare. 1994;22:341---2.

11.Oliveira CRD. Occupational exposure to anesthetic gases residue.RevBrasAnestesiol.2009;59:110---24.

12.BriggsG,MaycockJ.Theanaestheticmachine.Anaesth Inten-siveCareMed.2013;14:94---8.

13.Ishizawa Y. Specialarticle: generalanesthetic gases andthe globalenvironment.AnesthAnalg.2011;112:213---7.

14.TankóB, MolnárL,FülesdiB, etal. Occupationalhazardsof halogenatedvolatileanestheticsandtheirprevention:review oftheliterature.JAnesthClinRes.2014;5:426.

15.Va˘ısmanAI.Workingconditionsintheoperatingroomandtheir effect on the health of anesthetists. Eksp Khir Anesteziol. 1967;12:44---9.

16.CohenEN, BrownBW,BruceDL.Occupationaldiseaseamong operatingroom personnelanationalstudy---reportofanad hoccommitteeontheeffectoftraceanestheticsonthehealth ofoperatingroompersonnel.AmericanSocietyof Anesthesiol-ogists.Anesthesiology.1974;41:321---40.

17.NIOSH. Criteria for a recommended standard: occupational exposuretoanestheticgasesandvapors;1977.

18.HealthandSafetyExecutive(UK).Occupationalexposurelimits; 1996.

19.VaneLA,AlmeidaNetoJTP,CuriPR,etal.Oefeitodosistema Venturininaprevenc¸ãodepoluic¸ãodesalacirúrgica.RevBras Anestesiol.1990;40:159---65.

20.SouzaKM,BrazLG,NogueiraFR,etal.Occupationalexposure toanestheticsleadstogenomicinstability,cytotoxicityand pro-liferativechanges.MutatRes.2016:791---2,42---8.

21.AIA.AmericanInstituteofArchitects.Guidelinesfor construc-tionandequipmentofhospitalsandmedicalfacilities;1993. 22.Turpin BJ,HuntzickerJJ. Identification ofsecondaryorganic

aerosol episodes and quantitation of primary and secondary organicaerosolconcentrations duringSCAQS.AtmosEnviron. 1995;29:3527---44.

23.Chinelato AR, FroesNDTC. Genotoxic effects on profession-alsexposed toinhalational anesthetics. RevBrasAnestesiol. 2002;52:79---85.

24.AraujoTK,daSilva-GreccoRL,BisinottoFMB,etal.Genotoxic effectsofanestheticsinoperatingroompersonnelevaluatedby micronucleustest.JAnesthesiolClinSci.2013;2:26.

25.CostaPaesER,BrazMG,LimaJT,etal.DNAdamageand antiox-idant status in medical residents occupationally exposed to wasteanestheticgases.ActaCirBras.2014;29:280---6. 26.ChaoulMM,BrazJR,LucioLM,etal.Doesoccupational

expo-suretoanestheticgasesleadtoincreaseofpro-inflammatory cytokines?InflammRes.2015;64:939---42.

27.MastrangeloG,ComiatiV,dell’AquilaM,etal.Exposureto anes-theticgasesandparkinsondisease.BMCNeurol.2013;13:194. 28.Casale T, Caciari T, Rosati MV, et al. Anesthetic gases and

occupationally exposed workers. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;37:267---74.

29.RochaTL,Dias-JuniorCA,Possomato-VieiraJS,etal. Sevoflu-raneinducesDNAdamagewhereasisoflurane leadsto higher

antioxidative status in anesthetized rats. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:264971.

30.Braz MG, Karahalil B. Genotoxicity of anesthetics evaluated invivo(animals).BiomedResInt.2015;2015:280802.

31.BrazMG,BrazLG,BarbosaBS,etal.DNAdamageinpatients whounderwentminimallyinvasivesurgeryunderinhalationor intravenousanesthesia.MutatRes.2011;726:251---4.

32.OroszJE,BrazLG,FerreiraAL,etal.Balancedanesthesiawith sevofluranedoesnotalterredoxstatusinpatientsundergoing surgicalprocedures.MutatResGenetToxicolEnvironMutagen. 2014;773:29---33.

33.Nogueira FR, Braz LG, Andrade LR, et al. Evaluation of genotoxicity of general anesthesia maintained with desflu-rane in patientsunder minor surgery. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2016;57:312---6.

34.ChandrasekharM,RekhadeviPV,SailajaN,etal.Evaluationof geneticdamageinoperatingroompersonnelexposedto anaes-theticgases.Mutagenesis.2006;21:249---54.

35.SzyfterK,StacheckiI,Kostrzewska-PoczekajM,etal.Exposure tovolatileanaestheticsisnotfollowedbyamassiveinduction ofsingle-strandDNAbreaksinoperationtheatrepersonnel.J ApplGenet.2016;57:343---8.

36.NorppaH.Cytogeneticbiomarkersandgeneticpolymorphisms. ToxicolLett.2004;149:309---34.

37.TiceRR, AgurellE, AndersonD, etal. Singlecell gel/comet assay:guidelinesforinvitroandinvivogenetictoxicology test-ing.EnvironMolMutagen.2000;35:206---21.

38.Sanders RD,Weimann J,Maze M. Biologiceffects of nitrous oxide: a mechanistic and toxicologic review. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:707---22.

39.Sardas¸ S, Aygün N, Gamli M, et al. Use of alkaline Comet assay(singlecellgelelectrophoresistechnique)todetectDNA damagesinlymphocytesofoperatingroompersonnel occupa-tionally exposedto anaesthetic gases.Mutat Res. 1998;418: 93---100.

40.ErogluA,CelepF,ErciyesN.Acomparisonofsisterchromatid exchanges in lymphocytes of anesthesiologists to nonanes-thesiologists in the same hospital. Anesth Analg. 2006;102: 1573---7.

41.Wro´nska-NoferT,NoferJR,JajteJ,etal.OxidativeDNA dam-ageandoxidativestressinsubjectsoccupationallyexposedto nitrousoxide(N2O).MutatRes.2012;731:58---63.

42.ThomasP,HollandN,BolognesiC,etal.Buccalmicronucleus cytomeassay.NatProtoc.2009;4:825---37.

43.BonassiS,ZnaorA,CeppiM,etal.Anincreasedmicronucleus frequencyinperipheralbloodlymphocytespredictstheriskof cancerinhumans.Carcinogenesis.2007;28:625---31.

44.WiesnerG,HoeraufK,SchroegendorferK,etal.High-level,but notlow-level,occupationalexposuretoinhaledanestheticsis associatedwithgenotoxicityinthemicronucleusassay.Anesth Analg.2001;92:118---22.

45.BilbanM,JakopinCB,OgrincD.Cytogenetictestsperformed onoperatingroompersonnel(theuseofanaestheticgases).Int ArchOccupEnvironHealth.2005;78:60---4.

46.BonassiS,CoskunE,CeppiM,etal.TheHUmanMicroNucleus projectoneXfoLiatedbuccalcells(HUMN(XL)):theroleof life-style,hostfactors,occupationalexposures,healthstatus,and assayprotocol.MutatRes.2011;728:88---97.

47.Bolognesi C, Bonassi S, Knasmueller S, et al. Clinical appli-cation of micronucleus test in exfoliated buccal cells: a systematicreviewandmetanalysis.MutatResRevMutatRes. 2015;766:20---31.

48.CeppiM,BiasottiB,FenechM,etal.Humanpopulationstudies withtheexfoliatedbuccalmicronucleusassay:statisticaland epidemiologicalissues.MutatRes.2010;705:11---9.

50.Gasparovic AC, Jaganjac M, Mihaljevic B, et al. Assays for the measurement of lipid peroxidation. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;965:283---96.

51.HalliwellB. Free radicals, antioxidants,and humandisease: curiosity,cause,orconsequence?Lancet.1994;344:721---4. 52.Lee YM, Song BC, Yeum KJ. Impact of volatile

anesthet-ics on oxidative stress and inflammation. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:242709.

53.MalekiradAA,RanjbarA,RahzaniK,etal.Oxidativestressin operatingroompersonnel:occupationalexposuretoanesthetic gases.HumExpToxicol.2005;24:597---601.

54.IzdesS,SardasS,KadiogluE,etal.DNAdamage,glutathione, andtotalantioxidantcapacityinanesthesianurses.Arch Envi-ronOccupHealth.2010;65:211---7.

55.TürkanH,Aydin A,SayalA.Effect ofvolatileanestheticson oxidative stressduetooccupationalexposure.WorldJSurg. 2005;29:540---2.